Abstract

Structural defects strongly impact the electrical transport properties of graphene nanostructures. In this Perspective, we give a brief overview of different types of defects in graphene and their effect on transport properties. We discuss recent experimental progress on graphene self-repair of defects, with a focus on in situ transmission electron microscopy studies. Finally, we present the outlook for graphene self-repair and in situ experiments.

Ideal graphene is a one-atom-thick layer of carbon atoms that are perfectly arranged in a two-dimensional honeycomb lattice. Each carbon atom is coordinated with three other carbon atoms, with identical 120° in-plane bonding angles. The presence of structural defects breaks this perfect symmetry and opens a whole research area for studying the effect of structural defects on the mechanical, electrical, chemical, and optical properties of graphene. Sometimes their effect is beneficial. For example, defects are essential in chemical and electrochemical studies, where they create preferential bonding sites for adsorption of atoms and molecules, which can be used for gas and liquid sensing. On the other hand, defects pose a problem for electronics applications such as field-effect transistors and electrical interconnects because they can significantly lower the charge carrier mobility and thus increase the resistivity of graphene.1−4 While this is the general rule, there are also some exceptions where defects can be engineered in regular arrays to yield metallic or insulating states.5,6

Given their crucial impact on graphene properties, it is important to control defect formation and, if possible, find ways to repair existing defects. Important progress in this direction has recently been reported, where several in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) experiments have observed self-repair of graphene heated at high temperatures (>500 °C).7−9 Transmission electron microscopy is the perfect tool for this kind of study, as it combines atomic resolution with capabilities such as in situ heating and in situ electrical measurements. With this approach, correlating defects and electronic transport becomes a manageable task, as the experimenter can determine defects with atomic resolution and simultaneously measure the conductivity.

In this issue of ACS Nano,9Qi and co-workers fully exploit this potential of in situ TEM and observe, in real time and with atomic resolution, the effects of edge recrystallization induced by Joule heating on the conductivity of a single graphene nanoribbon. Details on this study are summarized in the second part of this Perspective, where they are accompanied by three other recent experiments on graphene self-repair. First, we provide an overview of the types of defects that are present in graphene, and we briefly discuss their effects on electron transport with an emphasis on graphene nanoribbons.

Defects in Graphene

In graphene, we can distinguish vacancy, impurity, and topological defects. In a vacancy defect, one or more atoms are removed from the lattice. In an impurity defect, one carbon atom is replaced by another atom of a different element. In a topological defect, no atom is removed from the lattice, but the bonding angles between the carbon atoms are rotated.

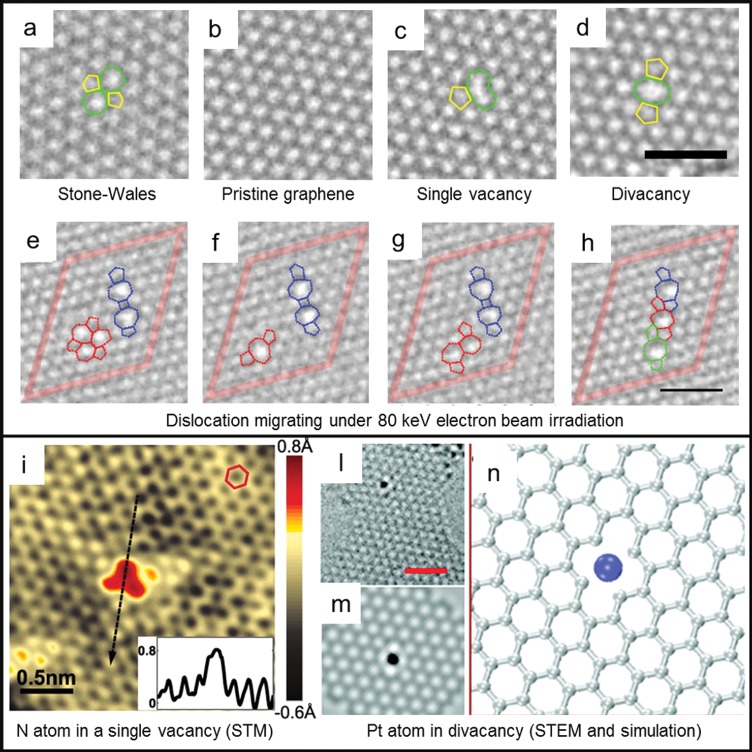

Vacancy defects in graphene are not easily formed. The energy required to sputter (or “knock-on”) a single atom out of the lattice is 18–20 eV.10 Such energy can be provided by bombarding ions in a plasma or by electrons with an energy >86 keV, which is typically achievable in a TEM (high-energy electrons are needed because the cross section for Coulomb scattering with a carbon atom is small). These kinds of vacancy defects act as strong scattering centers for the charge carriers in graphene, decreasing the localization length and disrupting the ballistic nature of electronic transport in graphene. For low or medium vacancy defect densities (1010–1012 cm–2, or 0.01–0.1% of the total area), mobility reduction is generally observed.11 For high defect densities (>1013 cm–2, 1% of the area), Anderson insulating behavior is predicted to develop.4 An example of a single-atom vacancy is shown in Figure 1c. The missing atom causes the lattice to rearrange in a five-carbon atom ring (5 ring) plus a 9 ring. The sp2 hybridization is broken, leaving one dangling bond unsaturated. Single vacancies can migrate and merge into divacancies. Such migration has a low activation energy (1.3 eV) and should already be observed at 200 °C12 (to our knowledge, single vacancy migration has not been recorded experimentally). Instead, divacancies (shown in Figure 1d) need to overcome a larger energy barrier to migrate (5–6 eV), which makes them much more stable than single vacancies.12,13 Divacancy migration under the influence of an 80 keV electron beam in a TEM was observed by Kotakoski et al.(13) (see Figure 1e–h). The migration involved only carbon bond rotation; no additional vacancies were created.

Figure 1.

Structural defects in graphene. (a–d) High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images of (a) Stone–Wales defect, (b) defect-free graphene, (c) single vacancy with 5–9 rings, (d) divacancy with 5–8–5 rings. Scale bar is 1 nm. (e–h) HRTEM image sequence of divacancy migration observed at 80 keV. Scale bar is 1 nm. Reprinted with permission from ref (13). Copyright 2011 American Physical Society. (i) Scanning transmission microscopy image of a single N atom dopant in graphene on a copper foil substrate. (Inset) Line profile across the dopant shows atomic corrugation and apparent height of the dopant. Reprinted with permission from ref (15). Copyright 2011 American Association for the Advancement of Science. (l,m) HRTEM images of a Pt atom trapped in divacancy and (n) simulated HRTEM image for the Pt vacancy complex. Scale bar is 1 nm. Reprinted from ref (14). Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society.

Whenever a vacancy is formed in graphene, an external element can replace the missing atom and fill the void in the lattice, forming an impurity defect. Single vacancies are ideal trapping sites for small atoms, such as B and N, whereas noble and transition metals, with larger atomic radii, prefer to rest on multivacancies.14 Zhao et al.(15) obtained chemical vapor deposition (CVD) graphene with N impurities by adding ammonia (NH3) as a precursor during the growth process. A high density of N atoms was obtained (0.34% of C atoms), which resulted in a considerable n-type doping of graphene. As can be seen from the scanning transmission microscopy (STM) images shown in Figure 1i, each N atom replaced a single C atom in the lattice, creating a perturbation in the local density of states that rapidly decayed in space (∼7 Å radius around the N atom). Conversely, Wang et al.(14) created vacancies in graphene with pulsed laser deposition and implanted different elements (Pt, Co, and In) afterward. In this case, the doping has been theoretically predicted to depend on the work function of the guest element (p-type if higher than the graphene work-function, n-type otherwise). Figure 1l–n shows an example of a Pt atom trapped in a divacancy. The binding energy of the platinum atom in this configuration is 6 eV, which also makes it stable during prolonged TEM observation at low voltage (60 keV).

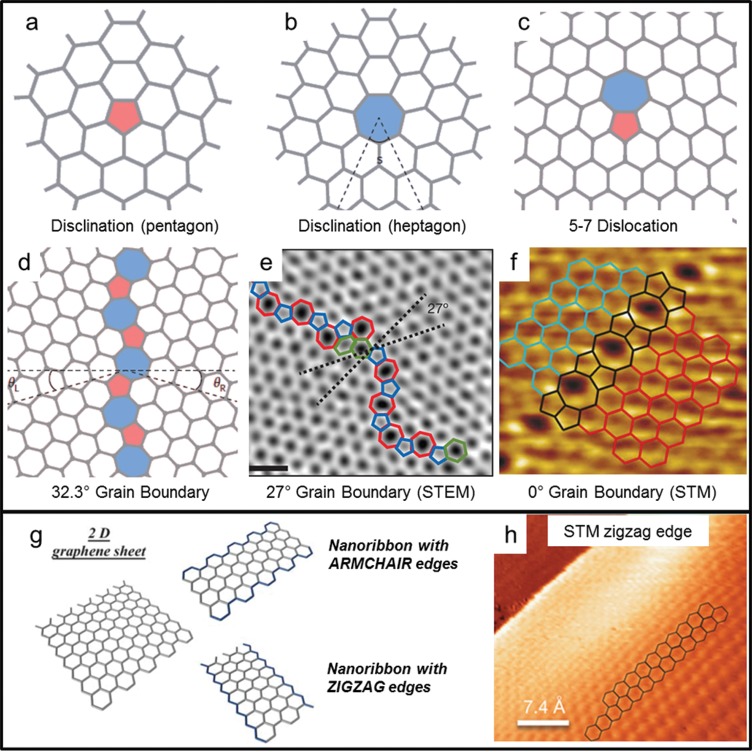

Finally, we consider topological defects in graphene. The simplest one is a single disclination, that is, the presence of a 5 or 7 ring that alters the regular 6 ring structure (see Figure 2a,b). Isolated disclinations are highly unlikely to develop in single-layer graphene because they require out-of-plane bulging of the graphene sheet and therefore have high formation energies.16 Dislocations are a combination of two or more complementary disclinations. The most basic dislocation is composed of a 5–7 ring pair, as shown in Figure 2c. Another interesting and frequently occurring dislocation is the Stone–Wales defect, which is composed of two 5–7 ring pairs (shown in Figure 1a).

Figure 2.

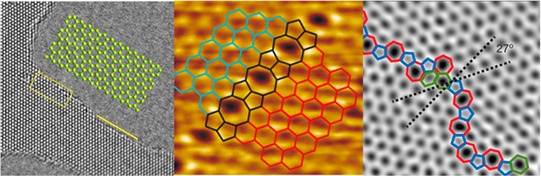

(a–f) Topological defects in graphene. (a,b) 5 ring and 7 ring disclinations, (c) 5–7 dislocation, (d) grain boundary with θ = 32.3° misorientation angle. Reprinted with permission from ref (16). Copyright 2014 Nature Publishing Group. (e) Aberration-corrected annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) of a grain boundary with θ = 27° misorientation angle. Scale bar is 0.5 nm. Reprinted with permission from ref (28). Copyright 2011 Nature Publishing Group. (f) Scanning transmission microscopy image of a 0° grain boundary, formed by 5 and 8 carbon atom rings. Reprinted with permission from ref (5). Copyright 2010 Nature Publishing Group. (g) Zigzag and armchair edges in monolayer graphene nanoribbons. Reprinted with permission from ref (20). Copyright 2010 Royal Society of Chemistry. (h) Atomic-resolution STM image of graphene edge structure on the sloped sidewall of SiC. Reprinted with permission from ref (19). Copyright 2014 Nature Publishing Group.

The most prominent examples of extended dislocations are grain boundaries (GB). Grain boundaries are formed in graphene whenever two separate domains (grains) with different crystallographic orientations are linked together. Figure 2d,e shows examples of a GB that connects two grains that are rotated by 32.3 and 27°, respectively. Experiments conducted on CVD-grown graphene have shown that GBs degrade the electronic transport in graphene. Tsen et al.(2) found that a single GB has a resistivity of 0.5 to 4 kΩ·μm, depending on the position of the Fermi level in the graphene grains. Grain boundaries are usually intrinsically n-type doped, while the surrounding graphene can be either n- or p-type. In the latter case, a sharp p–n junction is formed, which leads to a yet larger resistance. A special case of GB with zero rotation angle (see Figure 2f) was experimentally investigated by Lahiri et al.(5) In this case, the GB resembles a linear, periodic chain of 5–8 rings and it has a metallic nature (i.e., nonzero density of states at the Fermi level). The interested reader can find more information on structural defects in graphene in three recent reviews on the topic.12,16,17

Edge Defects in Graphene Nanoribbons

A graphene nanoribbon (GNR) is a narrow strip of graphene (width ranging from 1 to 100 nm) with a large length to width ratio. When the width of the nanoribbon is reduced below 20 nm, a sizable band gap can be opened in the band structure. The size of this band gap has been theoretically predicted to be in the 0.2–1.5 eV range,18 depending both on the GNR width and on its edge orientation (zigzag or armchair, see Figure 2g). The presence of a band gap makes GNRs good candidates for replacing traditional semiconductors in electronic devices such as field-effect transistors, tunnel barriers, and quantum dots.

Depending on the method adopted for GNR fabrication, the experimental band gap and mobility differ quite radically from the predicted values. The explanation for this behavior is mainly given by the presence of defects on the GNR edges, which alter the normal zigzag or armchair edge profiles and create localized states along the length of the GNR. This happened, for example, in fabrication using electron-beam lithography followed by oxygen plasma etching, which yields GNRs with rough edges. Stampfer et al.(3) have shown that a GNR fabricated following such a method behaves as a series of quantum dots, which gives an “effective energy band gap” of 110–340 meV, roughly 10 times higher than the predicted value (8 meV) in a 45 nm wide GNR. On the other hand, a recent experiment by Baringhaus et al.(19) showed ballistic transport in GNRs grown on the sidewalls of etched steps in SiC. As revealed by STM images (see Figure 2h), these GNRs have well-defined edge orientations and are mostly defect-free, which means that the charge carriers can travel a long distance (mean free path ∼16 μm) before undergoing inelastic scattering.

These, and many other experiments, highlight the importance of controlling the quality and the orientation of GNR edges. For more details on GNRs, their edges, and fabrication methods, we point the reader to specific reviews.20,21

Graphene Self-Healing and Recrystallization

Graphitization of thin carbon films (i.e., the process of graphite formation from amorphous carbon) was extensively studied in the 1980s.22 These experiments were carried out ex situ, where each sample was individually heated at a fixed temperature and imaged afterward in a TEM. It was found that graphitization takes place progressively in a temperature range of 2000–3000 °C. Almost 30 years later, prompted by the renewed interest in graphene, the topic of lattice recrystallization (or “healing”) was addressed with more modern, practical, in situ approaches. Here, we present four recent in situ (S)TEM experiments that use different approaches to achieve graphene lattice recrystallization. These include ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) healing,23 silicon-assisted growth,7 high-temperature healing,24 and recrystallization by Joule heating.9 We emphasize that, to achieve atomic-resolution imaging, graphene is always freestanding in these experiments.

Graphene Ultrahigh Vacuum Healing and Metal-Catalyzed Etching at Room Temperature

In the research conducted by Zan and collaborators,23 Ni and Pd metal particles were evaporated on top of CVD graphene and imaged with a STEM microscope in UHV (6 × 10–9 mbar). Under the effect of 60 keV electron-beam scanning, these metal particles acted as catalysts for etching holes in the graphene surface (see Figure 3a,b). In fact, the low energy of the electron beam would not be sufficient to create new vacancies in the bulk lattice (as the threshold for knock-on damage of single carbon atoms in graphene is 86 keV10), but it could be enough to displace atoms at graphene edges. The threshold for removing atoms at the edges has been calculated to be 62 keV (zigzag profile),25 which could be further lowered by the presence of the metal catalysts.

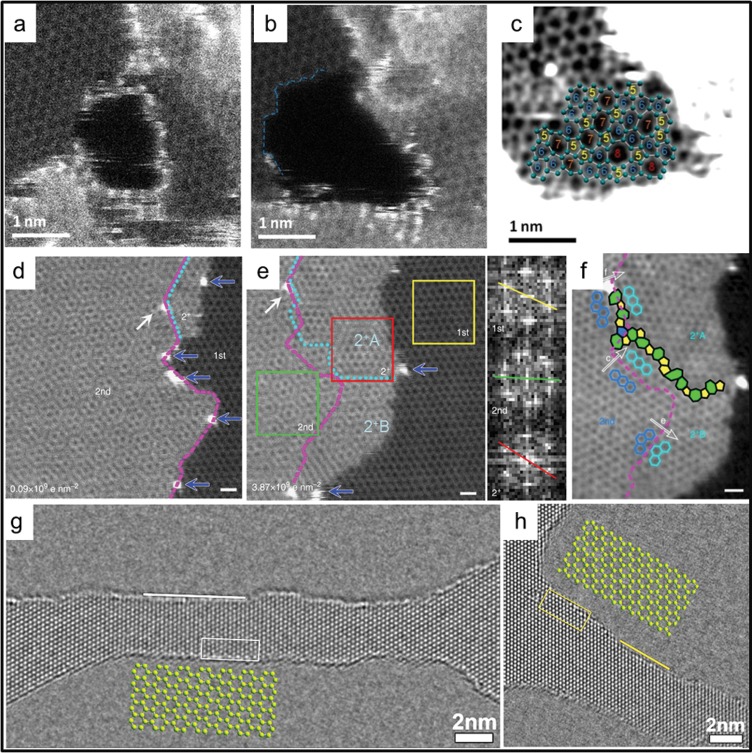

Figure 3.

Graphene self-repair experiments. (a–c) Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) (at 60 keV) images showing (a) a hole etched in graphene that is decorated with Pd atoms, (b) the stabilization of the hole in the absence of Pd atoms at the edge, and (c) the hole refilling with 5, 6, 7, and 8 carbon atom rings. The sample is at room temperature, in ultrahigh vacuum. Reprinted from ref (23). Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society. (d,e) Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM (at 60 keV) images showing (d) a graphene area which is single layer on the right side and bilayer on the left and (e) the same area after a cumulative electron dose of 3.87 × 109e nm–2. The inset shows the Fourier transform images corresponding to the 1st (yellow box), 2nd (green box), and 2+ (red box) layer of graphene. (f) Detail of the previous image, showing the grain boundary formed between the newly grown graphene (2+A and 2+B) and the original 2nd layer. The sample is heated to 500 °C. Scale bar is 0.5 nm. Reprinted with permission from ref (7). Copyright 2014 Nature Publishing Group. (g,h) High-resolution transmission electron microscopy images of nanoribbons in monolayer graphene sculpted at 300 keV at 600 °C and imaged at 80 keV at 600 °C. The ribbons in (g) and (h) are oriented, respectively, along the ⟨11̅00⟩ and ⟨12̅00⟩ directions. White and yellow lines indicate armchair and zigzag edges, respectively. Atom structure models for armchair and zigzag edges, outlined with open frames in the corresponding images, are enlarged and overlaid. Reprinted from ref (24). Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

Without the metal particles, the authors observed refilling and repairing of the holes, under the same electron-beam irradiation. As the whole experiment was conducted at room temperature, any heat-related repair process can be discarded. The authors concluded that the scanning electron beam could dislodge carbon adatoms from the graphene surface and drag them to the edge of the holes. There, they could rearrange in a random combination of 5, 6, 7, or 8 carbon atom rings and refill the hole (see Figure 3c).

Silicon-Assisted Growth of Graphene at High Temperature

In another experiment, Liu et al.(7) observed silicon-catalyzed graphene growth. A STEM microscope (operated at 60 keV) in high vacuum (1 × 10–7 mbar) was used to image CVD bilayer graphene and was simultaneously heated to 500 °C with an in situ TEM heating holder. The carbon needed for the growth originated from the hydrocarbons in the vacuum chamber of the microscope, after being decomposed on graphene by the electron beam (no growth was observed in areas not exposed by the electron beam). In contrast to the previously discussed experiment,23 room-temperature imaging did not result in hole refilling but simply in amorphous carbon deposition. This can be explained by the different vacuum conditions of the two microscopes: in worse vacuum, there are more hydrocarbons available, resulting in higher beam-induced carbon deposition rates. If this rate is too high, carbon atoms cannot form covalent bonds and keep accumulating in amorphous layers. Water molecules on the graphene surface (not completely removed in high vacuum) may also play a role in this process, catalyzing the deposition of amorphous carbon.

An example of the observed graphene growth is shown in Figure 3d–f. Looking at Figure 3d, the first layer area on the right is gradually covered by a second layer of graphene, extending from the left side. Silicon atoms (blue arrows) catalyze the growth and are pushed to the outermost edges of the newly formed graphene. As the authors explain, the graphene can either grow in the same crystal orientation as the seeding layer (layer 2+B in Figure 3e,f), or it can be rotated by 30° (layer 2+A). In the latter case, a grain boundary is formed. The rotation is caused by the presence of 5–7 edge defects in the original seeding layer before the growth had started. This proves that, in few-layer graphene heated at 500 °C, the growing orientation mainly follows the edge structure rather than the energetically favorable AB stacking.

Graphene STEM Sculpting at High Temperature

In the third experiment that we present, Xu et al.(24) used the STEM electron beam to sculpt graphene nanoribbons with 2 nm width and crystalline edges with defined orientation. In this case, the microscope was operated at 300 keV in order to knock the carbon atoms away from the lattice physically. Graphene was simultaneously heated to 600 °C using a dedicated in situ TEM holder. During the imaging process, the electron beam scanned the graphene surface with a short dwell time (10 μs). This only rarely created vacancies in the lattice, which were instantly repaired by refilling with carbon adatoms (highly mobile at 600 °C) present on the surface of graphene. When the dwell time was increased (10 ms), the beam-induced damage extended beyond repair and a hole was formed in the graphene. Using a computer script to move the beam slowly along a predefined path, the authors could pattern GNRs and nanopores with sub-nanometer accuracy. The edges of the patterned nanostructures maintained their crystalline structure because of the 600 °C temperature. Figure 3g,h shows an example of two GNRs, sculpted following either zigzag or armchair directions, exhibiting atomically sharp edges. This paper, rather than presenting a new graphene repair mechanism, exploits the high-temperature healing effects to achieve maskless, resist-free, and defect-free graphene patterning. With a few modifications, the method could also be extended to industrial e-beam lithography machines.

Graphene Nanoribbon Edge Recrystallization Induced by Joule Heating

In this issue of ACS Nano,9Qi and co-workers correlate, in real time, the conductivity of a GNR with its crystallinity, which is monitored at the atomic scale with high-resolution TEM imaging. Starting from a 8 nm wide multilayer graphene nanoribbon with rough edges (see Figure 3a in ref (9)), an increasing voltage (2–3 V) is applied across it, resulting in Joule heating and local temperatures that exceed 2000 K. This heating induces recrystallization of the nanoribbon edges, which rearrange along either zigzag or armchair profiles (see Figure 3b–d in ref (9)). As the voltage is increased and the temperature rises, the edges become smoother, the ribbon width shrinks, and the number of layers decreases (see Figure 3e–g in ref (9)). This recrystallization resulted in an overall increase in conductivity, despite the reduced width of the ribbon (see Figure 5a,b in ref (9)). This is an important, direct experimental confirmation of the influence of edge roughness and lattice crystallinity on graphene electronic transport.

To explain the mechanism of edge smoothing induced by Joule heating, Monte Carlo simulations were implemented. It was found that junctions between edges with different orientations (zigzag or armchair) develop a larger electrical resistance, which results in a higher local heat dissipation and, thus, higher temperature. Consequently, any edge protrusion was subject to a fast recrystallization and promptly flattened into a smooth edge.

One consequence of recrystallization induced by heating (either external or Joule) is the systematic formation of bonded edges (see Figure 6a in ref (7)). Any open edge in a bilayer, or multilayer, graphene sheet will “fuse” with the closest free edge available, as shown in Figure 2a–f from ref (9). For electrochemical studies, this could represent a disadvantage because there are no dangling bonds available for chemical functionalization. On the other hand, bilayer GNRs with closed edges could, in theory, have a finite band gap (up to 0.25 eV), depending on the twist angle between the two layers.

We note that a similar experiment was previously performed by Jia et al.(26) However, in that experiment, there was no correlation between width and conductivity of the sample nor any consideration on the number of graphene layers or the presence of bonded edges.

Outlook and Future Challenges

Different repair mechanisms for defects in graphene have been observed. Most of them are based on high-temperature annealing (>500 °C), and they require a carbon source to be initiated. The carbon is usually available as free adatoms on the graphene surface but can also be provided by the hydrocarbons present in the vacuum chamber of the TEM. Controlled Joule heating can be used to recrystallize the rough edges of plasma-etched GNRs, where the current flowing through the nanoribbons is regulated in order to induce self-repair, without causing physical breakdown.

The results obtained by Qi et al.(9) highlight that in situ TEM is the optimal instrument to study the effects of lattice repair on graphene conductivity. With small modifications, the experiment could be repeated on single-layer graphene and other two-dimensional materials, such as layered transition metal dichalcogenides (MoS2, WSe2, MoSe2, WS2, etc.), phosphorene, silicene, and many others.

While the current focus of the field is on controlling the annealing processes in such a way that one can make defect-free graphene nanostructures, a next stage will likely be to create single defects within perfect graphene deliberately (e.g., a small pore, a single step in a zigzag edge, or replacing a single C atom by a Pt atom), with the same level of perfection. This advance would open up many applications from electronic devices to catalysis. For example, with STEM, one could create a vacancy inside a GNR at a prechosen site, refill it with a Si or Pt adatom, and subsequently explore the interaction of a single Pt atom with H2 or other gases in an environmental TEM.

To fabricate graphene nanostructures, the fine probe of STEM can be optimally used for sculpting at the atomic level and in any shape, with precision higher than that with conventional TEM. To verify what has been made, one can use the same STEM, but with a voltage below the knock-on energy. Thus, for optimal operation, one needs a STEM that can rapidly switch from 100 keV (sculpting) to 60 keV (imaging). An interesting geometry to sculpt in graphene would be a nanoribbon with a nanopore in its center. In fact, it has been hypothesized that this configuration could be used for sequencing DNA with single-base resolution.27

These and other future experiments will pave the way for the fabrication of reliable, defect-controlled graphene devices. In situ TEM plays a crucial role in this expedition, as it provides a wonderful workbench for real-time graphene engineering.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC), project “NEMinTEM”, number 267922, and by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO/OCW), as part of the Frontiers of Nanoscience program.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Haskins J.; Kınacı A.; Sevik C.; Sevinçli H.; Cuniberti G.; Çağın T. Control of Thermal and Electronic Transport in Defect-Engineered Graphene Nanoribbons. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 3779–3787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsen A. W.; Brown L.; Levendorf M. P.; Ghahari F.; Huang P. Y.; Havener R. W.; Ruiz-Vargas C. S.; Muller D. A.; Kim P.; Park J. Tailoring Electrical Transport Across Grain Boundaries in Polycrystalline Graphene. Science 2012, 336, 1143–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stampfer C.; Güttinger J.; Hellmüller S.; Molitor F.; Ensslin K.; Ihn T. Energy Gaps in Etched Graphene Nanoribbons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 056403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lherbier A.; Dubois S. M.-M.; Declerck X.; Niquet Y.-M.; Roche S.; Charlier J.-C. Transport Properties of Graphene Containing Structural Defects. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 075402. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri J.; Lin Y.; Bozkurt P.; Oleynik I. I.; Batzill M. An Extended Defect in Graphene as a Metallic Wire. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 326–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazyev O. V.; Louie S. G. Electronic Transport in Polycrystalline Graphene. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 806–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Lin Y.-C.; Lu C.-C.; Yeh C.-H.; Chiu P.-W.; Iijima S.; Suenaga K. In Situ Observation of Step-Edge In-Plane Growth of Graphene in a STEM. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B.; Schneider F. F.; Xu Q.; Pandraud G.; Dekker C.; Zandbergen H. Atomic-Scale Electron-Beam Sculpting of Near-Defect-Free Graphene Nanostructures. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 2247–2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Z. J.; Daniels C.; Hong S. J.; Park Y. W.; Meunier V.; Drndić M.; Johnson A. T. C. Electronic Transport of Recrystallized Freestanding Graphene Nanoribbons. ACS Nano 2015, 10.1021/nn507452g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. W.; Luzzi D. E. Electron Irradiation Effects in Single Wall Carbon Nanotubes. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 90, 3509–3515. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-H.; Cullen W. G.; Jang C.; Fuhrer M. S.; Williams E. D. Defect Scattering in Graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 236805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banhart F.; Kotakoski J.; Krasheninnikov A. V. Structural Defects in Graphene. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 26–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotakoski J.; Krasheninnikov A. V.; Kaiser U.; Meyer J. C. From Point Defects in Graphene to Two-Dimensional Amorphous Carbon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 105505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Wang Q.; Cheng Y.; Li K.; Yao Y.; Zhang Q.; Dong C.; Wang P.; Schwingenschlögl U.; Yang W.; et al. Doping Monolayer Graphene with Single Atom Substitutions. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L.; He R.; Rim K. T.; Schiros T.; Kim K. S.; Zhou H.; Gutiérrez C.; Chockalingam S. P.; Arguello C. J.; Pálová L.; et al. Visualizing Individual Nitrogen Dopants in Monolayer Graphene. Science 2011, 333, 999–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazyev O. V.; Chen Y. P. Polycrystalline Graphene and Other Two-Dimensional Materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 9, 755–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings A. W.; Duong D. L.; Nguyen V. L.; Tuan D. V.; Kotakoski J.; Vargas J. E. B.; Lee Y. H.; Roche S. Charge Transport in Polycrystalline Graphene: Challenges and Opportunities. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 5079–5094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son Y.-W.; Cohen M. L.; Louie S. G. Energy Gaps in Graphene Nanoribbons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 216803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baringhaus J.; Ruan M.; Edler F.; Tejada A.; Sicot M.; Taleb-Ibrahimi A.; Li A.-P.; Jiang Z.; Conrad E. H.; Berger C.; et al. Exceptional Ballistic Transport in Epitaxial Graphene Nanoribbons. Nature 2014, 506, 349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia X.; Campos-Delgado J.; Terrones M.; Meunier V.; Dresselhaus M. S. Graphene Edges: A Review of Their Fabrication and Characterization. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L.; Wang J.; Ding F. Recent Progress and Challenges in Graphene Nanoribbon Synthesis. ChemPhysChem 2013, 14, 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goma J.; Oberlin M. Graphitization of Thin Carbon Films. Thin Solid Films 1980, 65, 221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Zan R.; Ramasse Q. M.; Bangert U.; Novoselov K. S. Graphene Reknits Its Holes. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 3936–3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q.; Wu M.-Y.; Schneider G. F.; Houben L.; Malladi S. K.; Dekker C.; Yucelen E.; Dunin-Borkowski R. E.; Zandbergen H. W. Controllable Atomic Scale Patterning of Freestanding Monolayer Graphene at Elevated Temperature. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 1566–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotakoski J.; Santos-Cottin D.; Krasheninnikov A. V. Stability of Graphene Edges under Electron Beam: Equilibrium Energetics versus Dynamic Effects. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia X.; Hofmann M.; Meunier V.; Sumpter B. G.; Campos-Delgado J.; Romo-Herrera J. M.; Son H.; Hsieh Y.-P.; Reina A.; Kong J.; et al. Controlled Formation of Sharp Zigzag and Armchair Edges in Graphitic Nanoribbons. Science 2009, 323, 1701–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha K. K.; Drndić M.; Nikolić B. K. DNA Base-Specific Modulation of Microampere Transverse Edge Currents through a Metallic Graphene Nanoribbon with a Nanopore. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P. Y.; Ruiz-Vargas C. S.; van der Zande A. W.; Whitney W. S.; Levendorf M. P.; Kevek J. W.; Garg S.; Alden J. S.; Hustedt C. J.; Zhu Y.; et al. Grains and Grain Boundaries in Single-Layer Graphene Atomic Patchwork Quilts. Nature 2011, 469, 389–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]