Abstract

Objective. Acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (ASTEMI) is accompanied by increased expression of inflammation and decreased expression of anti-inflammation. IL-37 was found to be involved in the atherosclerosis-related diseases and increased in acute coronary syndrome. However, the level of IL-37 in blood plasma and leukocytes from patients with ASTEMI after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has not been explored. Methods. We collected peripheral venous blood from consented patients at 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h after PCI and healthy volunteers. Plasma IL-37, IL-18, IL-18-binding protein (BP), and high sensitive C reaction protein (hs-CRP) were quantified by ELISA and leukocytic IL-37 and ICAM-1 by immunoblotting. Results. Plasma IL-37, IL-18, and IL-18 BP expression decreased compared to those in healthy volunteers while hs-CRP level was high. Both leukocytic IL-37 and ICAM-1 were highest expressed at 12 h point but significantly decreased at 48 h point. Conclusion. These findings suggest L-37 does not play an important role in the systematic inflammatory response but may be involved in leukocytic inflammation in ASTEMI after PCI.

1. Introduction

Despite modern reperfusion strategies have been well accepted around the world, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) still remains a leading cause of death worldwide. This suggests that AMI patients still need more understanding of potential pathophysiology for recurrent events of treatment especially in the early post-ACS period. So far, the systemic inflammatory response after AMI has been well described and may play an important role in series of events after AMI. Both circulating inflammatory markers, such as interleukin- (IL-) 6 and high sensitive C reaction protein (hs-CRP), as well as circulating inflammatory cells, including leukocytes and inflammatory monocytes, are elevated acutely after an AMI event in a temporal pattern that corresponds to elevated event rates and is predictive of recurrent events [1].

Anti-inflammation strategy is a good option of improving treatment for patients after AMI. Anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 are involved in the events of early AMI. The ratio of IL-18/IL-10 is found as an indicator for prognosis of AMI [2, 3]. IL-37 is a recently found anti-inflammatory cytokine in the IL-1 ligand family and proved as a fundamental inhibitor of innate immunity [4]. IL-37 was elevated in some inflammatory diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, atopic dermatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus [5–8], indicating IL-37 may have potential protective effect on inflammatory diseases. IL-37 is found to be increased in patients with acute coronary syndrome [9] but not investigated in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Additionally, IL-37 is normally expressed at low levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), mainly monocytes, and dendritic cells (DCs) [9], which is rapidly upregulated in the inflammatory context after AMI. IL-37 effectively suppresses the activation of macrophage and DCs [10], and therefore IL-37 may conversely inhibit the production of inflammatory cytokines in PBMCs and DCs after AMI. Given that IL-37 may be associated with the development of atherosclerosis, we hypothesize that IL-37 may play a potential role in the inflammation response including plasma and leukocytes in AMI patients after PCI.

So IL-37, as a new anti-inflammatory cytokine, may suppress immune responses and inflammation [11]. Inflammation is an important step after AMI. Understanding of IL-37 expression helps us further to explore that role and effect of IL-37 in AMI situation. Since it is also reported that a complex of the IL-37 and IL-18-binding protein reduces IL-18 activity [12], we wanted to explore (1) the expression of plasma and leukocytic IL-37 in early period after AMI; (2) the possible relationship between plasma IL-37, IL-18, and IL-18BP; and (3) the possible inhibitory effect of IL-37 on ICAM-1 in leukocytes.

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

β-Actin antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas, USA), and HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-human IgG was purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA, USA); ICAM-1 and IL-18 antibody were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). IL-37 was purchased from Adipogen AG, Liestal, Switzerland, IL-18 from MBL, Nagoya, Japan, IL-18BP from RayBiotech, Norcross GA, USA, and hs-CRP from Elisa Biotech (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Patients Population

From October, 2013, to April, 2014, a total of 112 cases of healthy volunteers (56) and patients (56) with ASTEMI agreed to participate in this test. STEMI was defined as chest pain suggestive of myocardial ischemia for at least 30 minutes before hospital admission and the electrocardiogram (ECG) with new ST-segment elevation in 2 or more contiguous leads of 0.2 mV or more in leads V2 to V3 and/or 0.1 mV or more in other leads. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients presenting with STEMI after 12 hours from symptom onset; (2) patients presenting with vasospastic angina (as determined by the resolution of ST-segment elevation and relief of symptoms after an IV administration of nitroglycerin); (3) patients over 75 years old; (4) recent (<1 week) systemic or local inflammation disease; (5) organ (liver, kidney) dysfunction; (6) cardiogenic shock.

Emergency PCI procedure must be carried out on all patients within 2 hours. All patients will receive 300 mg aspirin and a loading dose of 600 mg clopidogrel before the procedure. Unfractionated heparin will be administered intravenously in boluses to maintain an activated clotting time of >250 seconds during the procedure. Administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors will be based on the physicians' discretion. PCI will be performed according to current international guidelines. The goals of the procedure are to achieve optimal angiographic efficacy of PCI at the infarct-related artery and minimize the risk of procedure-related complications. A full range of commercially available guiding catheters, balloon catheters, and guide wires will be readily available. All patients included in this trial will be treated according to the current American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines regarding poststenting management, which specify treatment with at least 100 mg of aspirin daily and 75 mg clopidogrel daily for at least 12 months after PCI. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and β-blockers will be administrated after PCI if no limitation exists.

2.3. Leukocytes and Blood Plasma Isolation

Blood collection from consented healthy volunteers and patients was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College. An approximate volume of 3 mL peripheral venous blood was collected from all patients at different time point (12 h, 24 h, and 48 h) after PCI procedure into the procoagulation tube and ethylenediaminetetra acetic acid (EDTA)-K2 anticoagulation tube separately. Sample collection from healthy volunteers was obtained in the morning. Plasma was isolated from blood sample in procoagulation tube after centrifugation at the speed of 3,000 rpm, 15 min. Leukocyte was isolated from blood sample in EDTA-K2 tube using erythrocyte lysis buffer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and then collected after centrifugation at the speed of 2000 r/min, 10 min. Leukocytic protein was stored at −80°C for immunoblotting.

2.4. Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was used to detect leukocytic IL-37 and ICAM-1. Samples were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 5% dry milk in TPBS (PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20) and then incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies (ICAM-1 antibody was diluted into 1 : 1000, IL-37 1 : 500, and β-blocker 1 : 1000) overnight at 4°C. After washing with TPBS, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase- (HRP-) linked secondary antibodies (1 : 5000 dilution with TPBS containing 5% dry milk) at room temperature for 1 h. Bands were developed using ECL and exposed on X-ray films. Band density was analyzed using NIH ImageJ software.

2.5. Elisa

Plasma hs-CRP, IL-18, IL-18BP, and IL-37 were quantified by ELISA kits. Plasma hs-CRP was just detected at 12 h point, while IL-18, IL-18BP, and IL-37 were detected at 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h point. Recombinant cytokines were used to construct standard curves. Absorbance of standards and samples was determined spectrophotometrically at 450 nm using a microplate reader (KHB labsystem wallscan k3, Thermo Scientific, Finland). Results were plotted against the standard curve. The assays were carried out according to the protocols provided by the manufacturer.

2.6. Statistic Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, and differences were considered significant when P < 0.05, as verified by Fisher post hoc test.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Baseline clinical characteristics on the basis of age, gender, and leukocyte count between healthy volunteers and patients with STEMI are presented in Table 1. Mean age, gender disturbance, and leukocyte count were balanced between the groups. Most patients have 2 or more cardiovascular risk factors, while few patients have single parameter (2 have only hypertension, 2 only diabetes, 4 only hypercholesterolemia, and 4 only smoking history). Most patients have one or two diseased arteries, while 3 cases have 3 diseased ones. And most patients were occluded in LAD or RCA, while only 3 cases were infarcted in LCX. Plasma hs-CRP was elevated and indicated high inflammation situation after AMI with PCI.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of healthy volunteers and patients with ASTEMI after PCI.

| Patients (n = 56) | Healthy populations (n = 56) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56.5 ± 1.82 | 56.7 ± 2.22 | 0.532 |

| Male gender | 46 | 40 | 0.605 |

| WBC (∗10E9/L) | 9.48 ± 0.62 | 8.65 ± 0.45 | 0.876 |

| Hs-CRP (mg/L) | 24.98 ± 3.33 | ||

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Hypertension | 28 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 | ||

| Hypercholesterolemia | 30 | ||

| Smoking history | 30 | ||

| Ischemic time (min) | |||

| Mean | 385 | ||

| Median | 245 | ||

| Number of diseased vessels | |||

| 1 | 24 | ||

| 2 | 23 | ||

| 3 | 6 | ||

| Infarct-related artery | |||

| LAD | 34 | ||

| LCX | 3 | ||

| RCA | 19 |

WBC: white blood cells; LAD: left anterior descending artery; LCX: left circumflex artery; RCA: right coronary.

3.2. Plasma IL-37, IL-18, and IL-18BP Decreased at Early Period

We tested plasma IL-37, IL-18, and IL-18BP expression at different time points (12 h, 24 h, and 48 h after PCI) in patients with STEMI with Elisa kit (Table 2). Both IL-37, IL-18, and IL-18BP expression were balanced but decreased at all time points in patients if compared to those in healthy volunteers (P < 0.05). We then test IL-37 and ICAM-1 expression in leukocytes to check cellular inflammation and anti-inflammation after PCI.

Table 2.

Plasma IL-37, IL-18, and IL-18BP expression decreased in 48 h after PCI procedure.

| Group | Patients (n = 56) | Healthy (n = 56) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 h | 24 h | 48 h | ||

| IL-37 (pg/mL) | 82.8 ± 14.79* | 82.2 ± 9.28* | 84.4 ± 13.35* | 120.6 ± 2.67 |

| IL-18 (pg/mL) | 46.9 ± 5.06* | 44.2 ± 5.28* | 43.1 ± 4.60* | 91.0 ± 2.80 |

| IL-18BP (pg/mL) | 231.9 ± 22.06* | 261.5 ± 24.18* | 234.6 ± 19.53* | 461.9 ± 62.06 |

Plasma IL-37, IL-18, and IL-18BP from healthy volunteers and patients at different time point were qualified by Elisa kit. Lower expression of both IL-37, IL-18, and IL-18BP was in patients compared to those in healthy volunteers (∗ P < 0.05). No difference of change in all plasma cytokines was expressed at different time point in the patients with ASTEMI after PCI.

3.3. Leukocytic IL-37 and ICAM-1 Expression Change

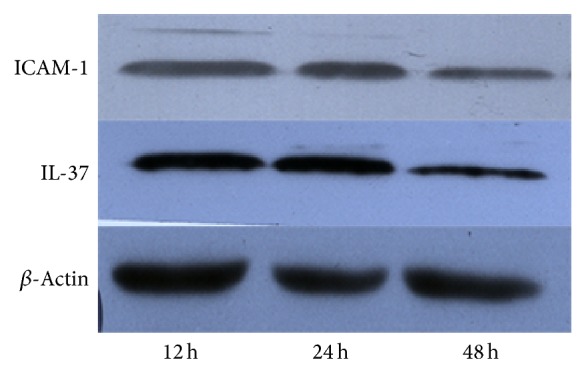

Leukocyte is an important cell involved in inflammatory response after AMI and expressed IL-37 under inflammation [4]. We analyzed cellular IL-37 and ICAM-1 protein expression with immunoblotting. We found that both cellular IL-37 and ICAM-1 protein were highest expressed at 12 h point but significantly decreased at 48 h point (Figure 1, P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Leukocytic IL-37 and ICAM-1 expression change at early period. Leukocytic IL-37 and ICAM-1 protein expression were detected with immunoblotting. Both leukocytic IL-37 and ICAM-1 protein were highest expressed at 12 h point but significantly decreased at 48 h point (P < 0.05, n = 48).

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated the expression of plasma IL-37 and leukocytic IL-37 in STEMI patients after PCI in early period. We found that plasma IL-37 did not increase and leukocytic IL-37 went down while plasma hs-CRP is high which indicates high inflammation response in the first 2 days after PCI. Plasma IL-18, which was found to be inhibited by IL-37, was also not increased under this situation.

STEMI is usually associated with inflammation and develops into severe complications. It is proved that inflammation is involved in atherosclerostic plaque formation and rupture, coronary thrombosis, and myocardial necrosis and repair after myocardial infarction [13–15]. Anti-inflammation strategy may be good for myocardial prognosis, but some anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 reduced in ACS patients, reflecting the imbalance in systemic cytokine response following an ACS [2, 16]. IL-37 is already proved as an anti-inflammatory cytokine and reported to be elevated in ACS patients [9], but we found that it decreased in patients after PCI in our study. This may be because PCI treatment could inhibit systematic IL-37 expression. Hereby, we found that systematic plasma IL-37 and leukocytic IL-37 decreased in the early period. In vivo expression of human IL-37 in mice reduces local and systemic inflammation in ConA-induced hepatitis and LPS challenge [17]. Therefore, IL-37 reduction may fail to inhibit systematic inflammation in patients with ASTEMI after PCI.

Not only hs-CRP but also IL-18 had been proved to be good indicators for prognosis for patients [18–20]. IL-18 is enhanced in STEMI situation [21–23], and the expression change of IL-18 is not reported before in patients after PCI. We found that IL-18 is decreased in the patients with PCI compared to that in healthy volunteers. A complex of the IL-37 and IL-18-binding protein reduces IL-18 activity [12]; but plasma IL-37, IL-18 and IL-18BP were increased in patients with ACS [9]. We wanted to test whether there is any relationship between changes of IL-18 and IL-37 in STEMI after PCI. The synchronous reduction of systematic IL-37 and IL-18 could not reveal the inhibitory effect of IL-37 on IL-18. The reduction of systematic IL-18 after PCI is not due to enhanced anti-inflammatory response. The ratio of IL-18/IL-10 was found to be an independent predictor of adverse events in patients with ACS [2, 3]. To decrease IL-18 and increase IL-10 are helpful for the recovery of patients with ACS [2]. The potential predictor effect of the ratio of IL-18/IL-37 on adverse events could be explored in the future. And to change the imbalance between inflammation and anti-inflammation is still meaningful. Although inflammatory markers such as CRP predict future cardiovascular events in ACS patients, when all inflammatory mediators are taken into account in a prospective analysis of risk, markers reflecting anti-inflammatory mechanisms may be better prognostic markers [18]. Furthermore, elevated level of plasma IL-37, IL-18, and IL-18BP had no correlation with the severity of the coronary artery stenosis [9], and decreased level of those was not related with that in our study.

Leukocyte is an important inflammatory cell in STEMI patients and is involved in myocardial necrosis and repair after STEMI [24]. Circulating monocytes could express high level of proinflammatory cytokines, TNF-alpha, and IL-6, as well as anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 [25]. ICAM-1 induces the interaction between leukocytes and endothelial cells [26], which is involved in the myocardial remodeling. We isolated circulating leukocytes and found reduction of both ICAM-1 and IL-37 in early period, indicating a balance of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory response in circulating leukocytes. We can suggest that ICAM-1 expression decreased because of IL-37, which is better to be confirmed by isolated leukocyte culture. Different from the systematic imbalance, the changes of IL-37 and ICAM-1 indicated a balance of inflammation and anti-inflammation on leukocytes. Leukocytes include several types including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes, so we cannot acutely tell which subtype has only or more IL-37 expression. We think neutrophils, most percentage of leukocytes, may be a potential good target to explore IL-37 expression and change in the future.

In this study, our baseline is healthy volunteers without some cardiovascular risk factors except age and gender. There is no report about systematic IL-37 expression in healthy volunteers before. We found that it is lower in the STEMI than that in the healthy, which may be because anti-inflammatory response is inhibited [2, 16]. Compared to other studies about anti-inflammatory cytokines, we can suggest that this is due to the inhibitory effect of anti-inflammatory response in ACS. Enhancing anti-inflammatory effect in STEMI may help to repair myocardial damage [27, 28]. How to increase IL-37 expression may be helpful and it is interesting to investigate that in future study. Furthermore, sample size is not too much in our study; we can investigate expression difference in different subgroup if we have more samples.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our study firstly demonstrates that systematic IL-37 expression was decreased in STEMI with PCI situation and on decline in leukocytes after PCI. These suggest that IL-37 does not play an important role in the systematic inflammatory response but may be involved in leukocytic inflammation in ASTEMI after PCI. More studies should be investigated for that.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Nature Science Foundation of China 81300123 and by College Students' Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program of Guangdong Province 1056013093.

Abbreviations

- ACS:

Acute coronary syndrome

- AMI:

Acute myocardial infarction

- DC:

Dendritic cell

- Hs-CRP:

High sensitive C reaction protein

- ICAM-1:

Intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IL:

Interleukin

- LPS:

Lipopolysaccharide

- PBMC:

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PCI:

Percutance coronary intervention.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contribution

Jilin Li is involved in experimental design, acquisition, and analysis of data and drafted the paper. Lan Chen, Xiangna Cai, and Xin Wang participated in the experiment and the acquisition and analysis of data. Xiangna Cai and Duanmin Xu were involved in drafting the paper. All authors read and approved the final paper. Xiangna Cai equally contributed to this paper as co-first authors.

References

- 1.Willerson J. T., Ridker P. M. Inflammation as a cardiovascular risk factor. Circulation. 2004;109(21, supplement 1):II2–II10. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111132.23469.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalikias G. K., Tziakas D. N., Kaski J. C., et al. Interleukin-18: interleukin-10 ratio and in-hospital adverse events in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Atherosclerosis. 2005;182(1):135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalikias G. K., Tziakas D. N., Kaski J. C., et al. Interleukin-18/interleukin-10 ratio is an independent predictor of recurrent coronary events during a 1-year follow-up in patients with acute coronary syndrome. International Journal of Cardiology. 2007;117(3):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nold M. F., Nold-Petry C. A., Zepp J. A., Palmer B. E., Bufler P., Dinarello C. A. IL-37 is a fundamental inhibitor of innate immunity. Nature Immunology. 2010;11(11):1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/ni.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imaeda H., Takahashi K., Fujimoto T., et al. Epithelial expression of interleukin-37b in inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2013;172(3):410–416. doi: 10.1111/cei.12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujita H., Inoue Y., Seto K., Komitsu N., Aihara M. Interleukin-37 is elevated in subjects with atopic dermatitis. Journal of Dermatological Science. 2013;69(2):173–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pei B., Xu S., Liu T., Pan F., Xu J., Ding C. Associations of the IL-1F7 gene polymorphisms with rheumatoid arthritis in Chinese Han population. International Journal of Immunogenetics. 2013;40(3):199–203. doi: 10.1111/iji.12007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song L., Qiu F., Fan Y., et al. Glucocorticoid regulates interleukin-37 in systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2013;33(1):111–117. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9791-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji Q., Zeng Q., Huang Y. Elevated plasma IL-37, IL-18, and IL-18BP concentrations in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Mediators of Inflammation. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/165742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu B. W., Zeng Q. T., Meng K., Ji Q. W. The potential role of IL-37 in atherosclerosis. Die Pharmazie. 2013;68(11):857–860. doi: 10.1691/ph.2013.3590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tetè S., Tripodi D., Rosati M., et al. IL-37 (IL-1F7) the newest anti-inflammatory cytokine which suppresses immune responses and inflammation. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 2012;25(1):31–38. doi: 10.1177/039463201202500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bufler P., Azam T., Gamboni-Robertson F., et al. A complex of the IL-1 homologue IL-1F7b and IL-18-binding protein reduces IL-18 activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(21):13723–13728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bentzon J. F., Otsuka F., Virmani R., Falk E. Mechanisms of plaque formation and rupture. Circulation Research. 2014;114(12):1852–1866. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burazor I., Vojdani A. Chronic exposure to oral pathogens and autoimmune reactivity in acute coronary atherothrombosis. Autoimmune Diseases. 2014;2014:8. doi: 10.1155/2014/613157.613157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frangogiannis N. G. The inflammatory response in myocardial injury, repair, and remodelling. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2014;11(5):255–265. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasqui A. L., di Renzo M., Bova G., et al. Pro-inflammatory/anti-inflammatory cytokine imbalance in acute coronary syndromes. Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 2006;6(1):38–44. doi: 10.1007/s10238-006-0092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulau A.-M., Fink M., Maucksch C., et al. In vivo expression of interleukin-37 reduces local and systemic inflammation in concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:2480–2490. doi: 10.1100/2011/968479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tziakas D. N., Chalikias G. K., Kaski J. C., et al. Inflammatory and anti-inflammatory variable clusters and risk prediction in acute coronary syndrome patients: a factor analysis approach. Atherosclerosis. 2007;193(1):196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartford M., Wiklund O., Hultén L. M., et al. Interleukin-18 as a predictor of future events in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2010;30(10):2039–2046. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.202697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubková L., Špinar J., Pávková Goldbergová M., Jarkovský J., Pařenica J. Inflammatory response and C-reactive protein value in patient with acute coronary syndrome. Vnitrni Lekarstvi. 2013;59(11):981–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Pouw Kraan T. C. T. M., Bernink F. J. P., Yildirim C., et al. Systemic toll-like receptor and interleukin-18 pathway activation in patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2014;67:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Mesallamy H. O., Hamdy N. M., El-Etriby A. K., Wasfey E. F. Plasma granzyme B in ST elevation myocardial infarction versus non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome: comparisons with IL-18 and fractalkine. Mediators of Inflammation. 2013;2013:8. doi: 10.1155/2013/343268.343268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brunetti N. D., Munno I., Pellegrino P. L., et al. Inflammatory cytokines imbalance in the very early phase of acute coronary syndrome: correlations with angiographic findings and in-hospital events. Inflammation. 2011;34(1):58–66. doi: 10.1007/s10753-010-9208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tardif J.-C., Tanguay J.-F., Wright S. S., et al. Effects of the P-selectin antagonist inclacumab on myocardial damage after percutaneous coronary intervention for non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: results of the SELECT-ACS trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;61(20):2048–2055. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.del Fresno C., Soler-Rangel L., Soares-Schanoski A., et al. Inflammatory responses associated with acute coronary syndrome up-regulate IRAK-M and induce endotoxin tolerance in circulating monocytes. Journal of Endotoxin Research. 2007;13(1):39–52. doi: 10.1177/0968051907078623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dieterich L. C., Huang H., Massena S., Golenhofen N., Phillipson M., Dimberg A. αb-crystallin/HspB5 regulates endothelial-leukocyte interactions by enhancing NF-κB-induced up-regulation of adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin. Angiogenesis. 2013;16(4):975–983. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9367-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baruch A., Van Bruggen N., Kim J. B., Lehrer-Graiwer J. E. Anti-inflammatory strategies for plaque stabilization after acute coronary syndromes topical collection on vascular biology. Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 2013;15(6, article 327) doi: 10.1007/s11883-013-0327-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seropian I. M., Toldo S., van Tassell B. W., Abbate A. Anti-inflammatory strategies for ventricular remodeling following St-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;63(16):1593–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]