Abstract

As brainstem nuclei are interconnected with several cortical structures and regulate several autonomic, cognitive, and behavioral functions, it might be important to place the brainstem within an important pathologic core in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Although there have been several postmortem studies reporting neuropathological alterations of the brainstem in AD, there has been no in-vivo structural neuroimaging study of the brainstem in the patients with AD. The aim of this study was to investigate differences in the brainstem volume and shape between patients with AD and elderly normal controls. Fifty AD patients (the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale ≥ 1) and 50 normal controls were recruited, and the brainstem volumes and deformations were compared between the AD and the controls. Patients with AD showed significant total volume [(mean ± SD) 21007 ± 1640 mm3]reduction in the brainstem compared with the controls [(mean ± SD) 22530 ± 1750 mm3] (P < 0.001). In addition, AD patients showed significant brainstem deformations in the upper posterior brainstem corresponding to the midbrain compared with the healthy individuals (false discovery rate corrected P < 0.05). This study is the first to explore brainstem volume change and deformations in AD. These structural changes in the midbrain areas might be at the core of the underlying neurobiological mechanisms of brainstem dysfunction with relevance to their various cognitive and behavioral symptoms such as memory impairment, sleep, and emotional disturbance in AD. However, further longitudinal studies might be needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, brainstem, MRI, shape analysis

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia that impacts daily living through memory loss and cognitive changes. In addition to the marked cognitive decline including memory impairment, AD is accompanied by a number of neuropsychiatric symptoms that are also equally as important as memory decline in the clinical profile [1]. For example, sleep disturbances such as falling asleep, maintaining nocturnal sleep, and emotional disturbances such as depression and agitation are known to be the most frequent and serious behavioral symptoms in AD [2].

Although considerable attention has been focused toward understanding brain cortical changes such as the medial temporal lobe, the precuneus, and the hippocampus associated with cognitive and behavioral symptoms during disease progression, the brainstem may also be a neuronal substrate for cognitive and behavioral problems in AD [2]. As brainstem nuclei are interconnected with several cortical structures and regulate several autonomic, cognitive, and behavioral functions, the brainstem may be part of an important pathologic core in AD progression. For instance, during the early stages of AD, brainstem neurodegeneration might result in erratic sleep patterns and emotional disturbances [3]. As the disease develops, brainstem neurodegeneration might cause other complications related to autonomic dysfunction, such as difficulties swallowing, breathing, and erratic blood pressure and arrhythmia [4]. Moreover, previous neuropathological studies have proven that brainstem change in the dorsal raphe nucleus, rather than the cortex, harbors the first detectable neurodegeneration in AD progression [5].

Despite its importance in the trajectory of AD, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no in-vivo study on the structural alterations of the brainstem in AD. On the basis of this, we attempted to investigate the shape and volume alterations of the brainstem in AD using MRI. A few automated subcortical segmentation methods have been introduced and validated recently. Among these, the Functional MRI of the Brain’s (FMRIBs) Integrated Registration and Segmentation Tool (FIRST) has been shown to be a reliable, fast, and accurate way of automated segmentation of subcortical structures [6]. In this study, we hypothesized that the midbrain (the upper posterior part of the brainstem), where the several nuclei associated with sleep, emotion, and autonomic functions are located, would be deformed in the AD group compared with the controls.

Methods

Participants

A total of 100 individuals participated in this study (50 patients with AD and 50 healthy elderly controls). All AD patients (a) fulfilled the National Institute of Neurological and Communication Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria for probable AD [7] and (b) had a score on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale of 1 or more [8]. We excluded from the study participants who had other neurological or psychiatric conditions (including other forms of dementia or depression) and those taking any psychotropic medications (e.g. cholinesterase inhibitors, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics). The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical and safety guidelines established by the local Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Korea. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their guardians participating in the study. All participants were right handed. Cognitive functions were evaluated using the Korean version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD-K), including Verbal Fluency (VF), a 15-item Boston Naming Test (BNT), Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE), Word List Memory (WLM), Word List Recall (WLR), Word List Recognition (WLRc), Constructional Praxis (CP), and Constructional Recall (CR) [9].

MRI acquisition

All participants underwent MRI scans on a 3 T whole-body scanner equipped with an eight-channel phasedarray head coil (Verio; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The scanning parameters of the T1-weighted three-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid gradientecho sequences were as follows: echo time = 2.5 ms, repetition time = 1900 ms, inversion time = 900 ms, flip angle = 91, field of view = 250 × 250 mm, matrix = 256 × 256, and voxel size = 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3.

Image processing

The FIRST tool, part of FSL (FMRIB’s Software Library, http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/), was used to automatically segment the hippocampus within the Bayesian Appearance Model frame work as described in a previous study [6]. During registration, the three-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid gradientecho images were transformed to the MNI 152 standard space by affine transformations on the basis of d.f. = 12. After registration, a subcortical mask was applied to locate the different subcortical structures, followed by segmentation on the basis of shape models and voxel intensities. Absolute volumes of subcortical structures were calculated, taking into account the transformations performed in the first stage. Finally, a boundary correction was used to determine which boundary voxels belonged to the structure or not. For subsequent classification of AD patients and the controls, the brainstem volumes were normalized to the total intracranial volume (TICV). The TICV was measured using the SIENAX software [10], part of FSL. The normalized brainstem volume was defined as NBV (Normalized Brainstem Volume) = mean TICV × brainstem volume/TICV. Group differences in normalized brainstem volume between AD patients and the controls were assessed using Student’s t-tests. As the FSL analysis suite does not provide the correction for multiple comparisons in the analysis of brainstem volumes, we set an uncorrected P-value less than 0.001 (two tailed) as a significant threshold in the statistical difference maps. This threshold, when an a priori hypothesis was present, was approximately equivalent to P-value less than 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons [11].

Volume and shape analysis

The FIRST creates a surface mesh for each subcortical structure using a deformable mesh model. The mesh is composed of a set of triangles, and the apex of adjoining triangles is called a vertex. The number of vertices for each structure is fixed so that corresponding vertices can be compared across individuals and between groups. Vertex correspondence is crucial for the FIRST methodology as it facilitates the investigation of localized shape differences through the examination of group differences in the spatial location of each vertex. Although the vertices retain correspondence, the surfaces reside in the native image space and thus have an arbitrary orientation/position. Therefore, the surfaces must all be aligned to a common space before investigating any group differences. The mean surface from the FIRST models is used as the target to which surfaces from the individual participants were aligned. Pose was removed by minimizing the sum-of-squares difference between the corresponding vertices of a participant’s surface and the mean surface. Group comparisons of vertices were carried out using F-statistics [6]. The effects of age, education, TICV, and sex were regressed out. The statistical significance threshold was set at a P-value of less than 0.05 [false discovery rate (FDR)] to resolve the problem of multiple comparisons. We referred to the Duvenroy Brainstem Atlas to determine the approximate anatomical location of our statistical maps [12].

Results

Demographic data

Table 1 shows the baseline demographic data in our different participant groups. No significant differences in sex, age, and education were observed between the AD group and the control group. Compared with the controls, patients with AD showed significantly poorer performances in BNT, MMSE, WLM, WLR, WLRc, and CR on CERAD-K neuropsychological tests (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants

| Control group (N=50) |

AD group (N=50) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [mean ± SD (years)] | 71.2 ± 4.3 | 72.1 ± 3.8 | NS |

| Education [mean ± SD (years)] |

9.4 ± 3.1 | 9.0 ± 4.2 | NS |

| Sex (male : female) | 23 : 27 | 24 : 26 | NS |

| CDR (mean ± SD) | 0 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | <0.0001 |

| CERAD-K battery (mean ± SD) | |||

| VF | 13.3 ± 3.9 | 6.2 ± 3.9 | <0.0001 |

| BNT | 12.7 ± 2.1 | 7.1 ± 2.3 | <0.0001 |

| MMSE | 28.4 ± 1.5 | 21.4 ± 3.3 | <0.0001 |

| WLM | 18.5 ± 4.5 | 7.0 ± 3.4 | <0.0001 |

| CP | 9.4 ± 1.5 | 6.7 ± 1.9 | <0.0001 |

| WLR | 7.7 ± 1.8 | 2.3 ± 1.8 | <0.0001 |

| WLRc | 9.9 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± 1.7 | <0.0001 |

| CR | 6.7 ± 2.9 | 3.2 ± 2.9 | <0.0001 |

| Brainstem volume [mean ± SD (mm3)] |

22530 ± 1750 | 21007 ± 1640 | <0.0001 |

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; BNT, 15-item Boston Naming Test; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; CERAD-K, the Korean version of Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; CP, Constructional Praxis; CR, Constructional Recall; MMSE, Mini Mental Status Examination; NS, nonsignificant; VF, Verbal Fluency; WLM, Word List Memory; WLR, Word List Recall; WLRc, Word List Recognition.

Volume and shape analysis

The total brainstem volumes were significantly smaller in the AD group [(mean ± SD) 21007 ± 1640 mm3] than inthe control group [(mean ± SD) 22530 ± 1750 mm3](Table 1, P < 0.001).

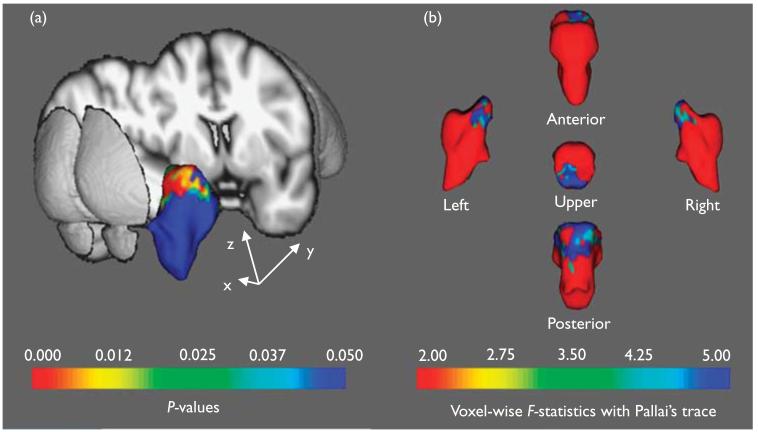

Although the location of the morphological changes could not be specifically pinpointed, the shape analysis showed more regionally contracted areas in the upper midbrain areas of the brainstem in the AD group compared with the controls. These deformations extended to the posterior portion (inferior colliculus) of the brainstem (Fig. 1, FDR corrected, P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Statistical maps corrected for age, education, and sex showing brainstem shape deformation in patients with AD relative to the control group. The upper posterior part of the brainstem that corresponds to the midbrain of the AD group is significantly deformed compared with the control group (FDR-corrected P <0.05). In (a), the figure shows the color coding of the surface reflecting the FDR-corrected P-values associated with the midbrain change in the AD group, whereas in (b), the color coding corresponds to the FDR-corrected F-static values. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; FDR, false discovery rate.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to elaborate morphological alterations of the brainstem in AD patients.

Current diagnostic clinical criteria for AD focus mostly on cognitive deficits produced by dysfunction of neocortical regions such as the entorhinal cortex and the posterior cingulate, with less consideration given to the neuronal substrate for AD-related noncognitive, behavioral, and psychological symptoms of dementia such as disturbances in mood, emotion, appetite, and wake–sleep cycle, as well as confusion, agitation, and depression[2,13]. The brainstem contains many different nuclei involved in functions ranging from controlling homeostasis and emotions to modulating cognitive functions of the cerebral cortex [2]. Consequently, a better understanding of brainstem involvement in the pathogenesis of AD might help clarify the precise neurobiological mechanisms underpinning the clinical course.

In this study, compared with the controls, the AD group showed significant deformations in the upper posterior part of the brainstem (corresponding to the midbrain), where several nuclei for various neurotransmissions are located [12]. Although there has been no structural neuroimaging study of brainstem in AD, these findings are in line with the previous postmortem studies that showed cell loss or neuropathological changes such as neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) in the brainstem in AD[2,14]. However, because the Braak and Braak’s neuropathological staging of AD is confined to allocortical and neocortical regions, neuropathological involvement of the brainstem in AD has been considered secondary to supratentorial changes [15,16]. Among the several structures in the brainstem, the nuclei of dorsal raphe (serotonergic), locus ceruleus (adrenergic), and substantia nigra (dopaminergic) have been mostly studied because they are responsible for the various cognitive and emotional symptoms in AD. These nuclei comprise the isodendritic core, whose neurons share morphological features, such as large somata, overlapping dendritic fields, predominantly poorly myelinated axons that extend to distant projection sites, and aminergic/cholinergic volume transmission [17]. The isodendritic core is involved in the modulation of many basic physiologic processes and is strongly connected with those areas of the cerebral cortex that undergo early neurofibrillary changes in AD [18].

A previous postmortem pathological study showed NFTs in the midbrain dorsal raphe nucleus even before NFTs retention in the transentorhinal region [19]. Interestingly, the NFT burden in the dorsal raphe nucleus was associated with the Braak and Braak stage, suggesting that brainstem areas are affected by AD before the supratentorial regions [19]. Observed pathological changes of the dorsal raphe nucleus in earlier stage AD drew new attention to the brainstem, leading to new studies and reviving old hypotheses [5]. In addition, because the dorsal raphe nucleus produces a great part of brain serotonin, its degeneration might be related to some behavioral symptoms such as depression and anxiety experienced by many AD patients [5].

In addition to pathological changes in the dorsal raphe nucleus, the locus ceruleus is also known to be affected by NFT and senile plaque in AD. A previous pathological study showed significant neuronal loss and NFTs in the locus ceruleus of patients with AD [20]. In addition, there was a significant association between locus ceruleus atrophy and the frequency of NFTs in the cortex [21], as well as a positive correlation of NFTs with the duration and severity of dementia [22]. Interestingly, an association has been reported between noradrenergic pathology in the locus ceruleus and the emergence of clinical symptoms of depression in AD [23].

Taken together with these neuropathological data, our in-vivo results suggest that the midbrain deformation in AD could be a disease progression marker analogous to the hippocampal structural change [24]. However, further large-scale longitudinal studies will be needed to verifythe validity of brainstem deformation in the clinical course of AD.

Our study had some limitations. First, the degree of symptoms in the AD group varied from mild to moderate, making it difficult to elucidate brainstem morphological change during the very early phases of AD. Further studies with very mild AD or mild cognitive impairment patients would be helpful for identifying whether brainstem morphological change could be marked earlier on the AD continuum. Second, as we only studied morphological changes in brainstem using MRI, we could not investigate the relationships between the pathological burden (i.e. the fibillar Aβ) and structural changes of the brainstem in AD. Further molecular and morphological imaging studies using amyloid ligand such as Pittsburgh compound B [25] would be needed to elucidate the precise neurobiological mechanisms behind brainstem changes in AD. Third, although we adopted the Duvenroy Brainstem Atlas [12] as the anatomical reference, we could not pinpoint the anatomical border of the brainstem subregion with deformation. Therefore, development of a subregion segmentation method based on the MRI atlas will be needed.

Conclusion

We showed deformations in the upper posterior midbrain in AD patients. These structural changes might be the core of the underlying neurobiological mechanisms of brainstem dysfunction and their relevance to various cognitive and behavioral symptoms in AD.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hahn C, Lim HK, Won WY, Ahn KJ, Jung WS, Lee CU. Apathy and white matter integrity in Alzheimer’s disease: a whole brain analysis with tractbased spatial statistics. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grinberg LT, Rueb U, Heinsen H. Brainstem: neglected locus in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neurol. 2011;2:42. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2011.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montplaisir J, Petit D, Lorrain D, Gauthier S, Nielsen T. Sleep in Alzheimer’s disease: further considerations on the role of brainstem and forebrain cholinergic populations in sleep-wake mechanisms. Sleep. 1995;18:145–148. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.3.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rub U, del Tredici K, Schultz C, Thal DR, Braak E, Braak H. The autonomic higher order processing nuclei of the lower brain stem are among the early targets of the Alzheimer’s disease-related cytoskeletal pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;101:555–564. doi: 10.1007/s004010000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simic G, Stanic G, Mladinov M, Jovanov-Milosevic N, Kostovic I, Hof PR. Does Alzheimer’s disease begin in the brainstem? Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2009;35:532–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2009.01038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patenaude B, Smith SM, Kennedy DN, Jenkinson M. A Bayesian model of shape and appearance for subcortical brain segmentation. Neuroimage. 2011;56:907–922. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JH, Lee KU, Lee DY, Kim KW, Jhoo JH, Kim JH, et al. Development of the Korean version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Packet (CERAD-K): clinical and neuropsychological assessment batteries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:P47–P53. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.1.p47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith SM, Zhang Y, Jenkinson M, Chen J, Matthews PM, Federico A, de Stefano N. Accurate, robust, and automated longitudinal and cross-sectional brain change analysis. Neuroimage. 2002;17:479–489. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashburner J, Csernansky JG, Davatzikos C, Fox NC, Frisoni GB, Thompson PM. Computer-assisted imaging to assess brain structure in healthy and diseased brains. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naidich TP, Duvernoy HM, Delman BN, Sorensen AG, Kollias SS, Haacke EM. Duvernoy’s Atlas of the human brain stem and cerebellum. Springer; Vienna, Austria: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jack CR, Jr, Albert MS, Knopman DS, McKhann GM, Sperling RA, Carrillo MC, et al. Introduction to the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parvizi J, Van Hoesen GW, Damasio A. The selective vulnerability of brainstem nuclei to Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:53–66. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200101)49:1<53::aid-ana30>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardy JA, Mann DM, Wester P, Winblad B. An integrative hypothesis concerning the pathogenesis and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1986;7:489–502. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(86)90086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramon-Moliner E, Nauta WJ. The isodendritic core of the brain stem. J Comp Neurol. 1966;126:311–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.901260301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Insausti R, Amaral DG, Cowan WM. The entorhinal cortex of the monkey: III. Subcortical afferents. J Comp Neurol. 1987;264:396–408. doi: 10.1002/cne.902640307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grinberg LT, Rub U, Ferretti RE, Nitrini R, Farfel JM, Polichiso L, et al. Brazilian Brain Bank Study Group. The dorsal raphe nucleus shows phospho-tau neurofibrillary changes before the transentorhinal region in Alzheimer’s disease. A precocious onset? Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2009;35:406–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2009.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zweig RM, Ross CA, Hedreen JC, Steele C, Cardillo JE, Whitehouse PJ, et al. The neuropathology of aminergic nuclei in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1988;24:233–242. doi: 10.1002/ana.410240210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mann DM, Yates PO, Marcyniuk B. Changes in Alzheimer’s disease in the magnocellular neurones of the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus and their relationship to the noradrenergic deficit. Clin Neuropathol. 1985;4:127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bondareff W, Mountjoy CQ, Roth M, Rossor MN, Iversen LL, Reynolds GP. Age and histopathologic heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s disease. Evidence for subtypes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:412–417. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800170026005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zubenko GS, Moossy J, Kopp U. Neurochemical correlates of major depression in primary dementia. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:209–214. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530020117023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albert MS, deKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rowe CC, Ng S, Ackermann U, Gong SJ, Pike K, Savage G, et al. Imaging beta-amyloid burden in aging and dementia. Neurology. 2007;68:1718–1725. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000261919.22630.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]