Abstract

In 2005, New Mexico created a single health plan to administer all publicly-funded behavioral health services. Our mixed-method study combined surveys, document review, and ethnography to examine this reform’s influence on culturally competent services (CCS). Participants were executives, providers, and support staff of behavioral healthcare agencies. Key variables included language access services and organizational supports, i.e., training, self-assessments of CCS, and maintenance of client-level data. Survey and document review suggested minimal effects on statewide capacity for CCS during the first three years of the reform. Ethnographic research helped explain these findings: (1) state government, the managed behavioral health plan and agencies failed to champion CCS; and (2) increased administrative requirements minimized time and financial resources for CCS. There was also insufficient appreciation among providers for CCS. Although agencies made progress in addressing language assistance services, availability and quality remained limited.

Keywords: Cultural appropriateness, health policy, mental health, mixed-method, rural

INTRODUCTION

The Federal government promotes National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) to help eliminate disparities in behavioral healthcare access and utilization due to inequities based on language, ethnicity, and race (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). National policy documents typically define culturally competent care as a set of behaviors, attitudes, and policies that facilitate effective work with individuals from different cultures (Office of Minority Health, 2001). Reports released by the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (2003) and other prominent groups (National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning & National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, 2004) call for the elimination of racial, ethnic, and linguistic disparities in access, quality of care, and disability burden through culturally competent services (CCS). The adoption of CCS within health and behavioral healthcare agencies may improve treatment for minority populations (Lieu et al., 2004; Opler, Ramirez, & Mougious, 2002) and individuals with limited English proficiency (Miranda et al., 2003; Ziguras, Klimidis, Lewis, & Stuart, 2003).

Critical gaps exist in literature on the uptake of CLAS standards in behavioral healthcare agencies and the effects of state reform on access to and quality of CCS. Only a small number of studies offer insight into the availability of language access services, organizational supports, and other forms of CCS at the agency level (Campbell & Alexander, 2002; Howard, 2003; Semansky, Altschul, Sommerfeld, Hough, & Willging, 2009; Vandervort & Melkus, 2003).

In this paper, we examine delivery of CCS to adults with serious mental illness (SMI) in New Mexico (NM), a state that initiated a major reform of publicly-funded behavioral healthcare in 2005. The reform sought to improve the availability and provision of language access services and organizational supports that promote CCS. Language access services included interpretation, bilingual care, translated materials, and signage. Organizational supports included training, agency self-assessments of culturally competent practices, and maintenance of client-level racial/ethnic and linguistic data. As part of the reform, the state government contracted with a single managed care organization, ValueOptions New Mexico (VONM), to oversee delivery of all publicly-funded services. This organization was also responsible for promoting adherence to the CLAS standards and facilitating agency and provider adoption and implementation of CCS.

Few studies have combined research methods to understand the effectiveness of state-mandated efforts to improve CCS, particularly in behavioral healthcare (Chow, Jaffee, & Snowden, 2003; Westbrook et al., 2007). We provide insight into contextual challenges affecting the capacity of community-based agencies to comply with basic CLAS mandates and to deliver CCS. First, we quantitatively assessed for changes between the first and third years of the reform using multiple measures of CCS. Second, we reviewed administrative data reports and contracts between the state and VONM to identify and examine CCS improvement strategies. Third, we undertook ethnography in a subset of agencies to illuminate how service providers approached CCS issues. Finally, we developed recommendations to improve CCS under the reform that policymakers in other states will find relevant to efforts to foster CCS.

Study Context

New Mexico has substantial need for language access services and CCS. Ethnic minorities comprise the numerical majority, and one-third of the population speaks a non-English language at home (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011; U.S. Census Bureau, 2003). Spanish and Diné (Navajo) are the two most common non-English languages spoken.

The state government placed a high priority on improving CCS as part of its large-scale transformation of behavioral healthcare (Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative, 2005). From the start, VONM was to employ staff dedicated to CCS. The reform was to promote and reimburse Native American healing and use of traditional counselors, and outreach to Hispanic people via community health workers, such as promotoras. It was also intended to streamline the fragmented services that 15 separate state departments and offices had historically managed, provided, or funded. Under this cost-neutral system change, no new monies were added to enhance service delivery in the public sector (Hyde, 2004). The state collaborated with VONM to develop uniform sets of services, standards, access procedures, utilization review protocols, and performance measures for all behavioral healthcare agencies.

Research Questions

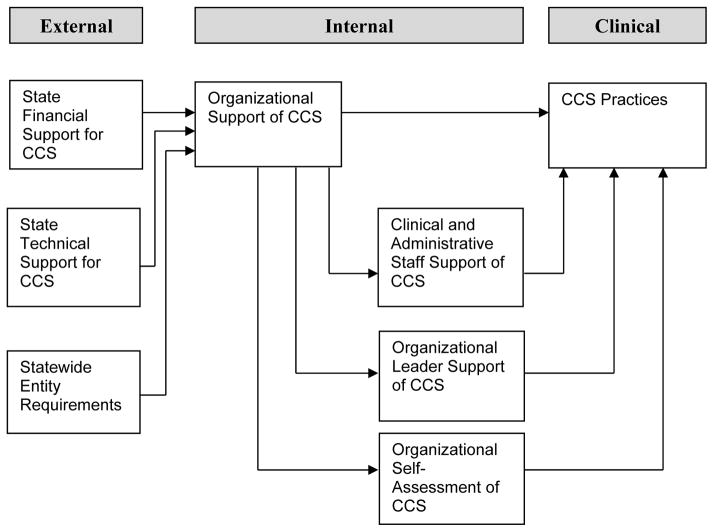

We examine two research questions pertaining to CCS in NM. First, did the reform achieve the desired goal of increasing availability of language access services and organizational supports for CCS? This question was answered by repeated surveys of community-based agencies regarding the prevalence of specific CCS practices. Second, what factors influenced the availability of CCS? This question was answered using a mixed-method approach with a particular focus on the contextual issues affecting delivery of such services. Because innovation adoption is more likely to occur when organizations have external (policy) and internal (agency) environments that are supportive of the change, we created a conceptual model to guide both data collection and analysis. Figure 1 delineates the relevant components of the environments that bear upon the availability, adoption, and implementation of CCS (Kimberly et al., 1990).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model for CCS Practices

METHODS

We implemented three research methods (statewide surveys, systematic document review, and ethnographic research) to address the research questions that were components of a long-term mixed-method assessment of the implementation and impact of the NM reform on services for low-income adults with SMI (Aarons, Sommerfeld, & Willging, 2011; Semansky et al., 2009; Semansky, Hodgkin, & Willging, 2011).

Survey Component

We conducted statewide surveys of community-based agencies that: (1) specialized in services for adults with SMI, i.e., bi-polar disorder, major depression, and schizophrenia; (2) accepted Medicaid or state funding for uninsured patients; and (3) comprised either a group practice or an agency. The survey occurred at two time points. For the initial survey, questions assessed agency experiences one year after reform implementation. Trained staff administered the survey via the telephone to senior agency leaders. A total 74 agencies participated in the survey at Time 1 (T1), August 2006–January 2007; and 78 two years later in Time 2 (T2), August 2008–January 2009. The response rate was 86% in T1 and 79% in T2 with 101 different agencies participating in at least one of the surveys.

Survey data and analysis

The survey assessed the general status of agencies under the reform and included a focus on CCS through structured questions that addressed the availability of bilingual staff, translated materials, training requirements, and the conduct of organizational self-assessments (e.g., internal inventories of agency-wide policies, practices, and procedures related to provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate services) (Office of Minority Health, 2001). Additionally, agency executives rated on a scale from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent) how well VONM worked towards increasing the availability of CCS in the past year.

To answer our first research question, we assessed whether there were changes in the number of agencies that had language access services and organizational supports identified in the CLAS standards between T1 and T2. For binary response indicators (Yes/No), we performed McNemar tests to assess for changes for the same agency between T1 and T2 (Tabachnick, 2007). For the scale measure, a matched pair t-test was used to assess the mean difference between T1 and T2. Confidence intervals were calculated at the ±.10 level. Using matched pair (agencies participating in both T1 and T2) analytical approaches reduced the maximum sample size of the analysis to 53, with fewer responses for individual items due to missing values. We conducted the same tests with subsets of agencies (e.g., only those operating in areas with large proportions of Native American or Hispanic populations) to determine if local demographic characteristics might be associated with change in culturally relevant agency attributes. Because the statistical results for these tests were identical, we report the most parsimonious model.

Two-thirds of agencies in the analyses operated as nonprofits (n=35) followed by 18.9% (n=10) as public sector and 15.1% as for-profits (n=8). Table 1 presents additional agency-level characteristics at T1. Medians and quartiles are reported due to data skewness. Though agencies differed in terms of the exact number of employed staff, most were small, with a median of 5.5 licensed mental health professionals (e.g., psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers) and 4 support staff. Fewer than half employed licensed substance abuse treatment professionals. Agencies served a racially/ethnically diverse clientele as indicated by medians for Hispanics (40%), Non-Hispanic Whites (28%), and Native Americans (2%). However, Native Americans comprised over 90% of the clientele for a subset of agencies (n=8). Overall, the primary financial source of agency payment was public sector funding sources (median=80%).

Table 1.

Agency Characteristics at T1

| N | Median | 25th Quartile | 75th Quartile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agency staff | ||||

| Lic. MH professional | 52 | 5.5 | 2.2 | 9.8 |

| Lic. SU professional | 52 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Admin. support | 53 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 7.5 |

| Client race/ethnicity | ||||

| Pct. Hispanic | 53 | 40.0 | 26.5 | 55.5 |

| Pct. Caucasian | 53 | 38.0 | 20.0 | 48.0 |

| Pct. Native American | 53 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 |

| Funding | ||||

| Pct. Public | 49 | 80.0 | 66.5 | 96.3 |

| Pct. Private Ins. | 49 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 15.0 |

Note. Lic. = Licensed; MH = Mental Health; SU = Substance Use; Pct. = Percentage; Ins. = Insurance.

Document Review Component

We systematically reviewed official state documents about the reform, including contracts with VONM and service delivery reports, and the demographics of service users. From the start of the reform, VONM was to comply with a number of CCS-related expectations: (1) compile a list of providers able to deliver CCS; (2) work with large community-based agencies to develop and evaluate their own progress in implementing plans to improve CCS; and (3) expand funding for Native American traditional counseling services and promotora outreach (Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative, 2005).

Ethnographic Component

We collected ethnographic data concerning the reform in general and cultural competency issues in particular from 14 agencies. Eight of the agencies were operated by or located in a community mental health center and provided both mental health and substance use services to adult populations, including those with persistent illnesses and the homeless. The remaining sites included two small group practices, three substance abuse treatment centers, and an outpatient program for homeless adults with co-occurring disorders. The agencies reflected the state’s range of provider organizations and ethnic diversity of catchment populations.

Ethnographic data collection and analysis

Ethnography is the systematic and in-depth description of cultural and social processes. Overlapping with our survey periods, ethnographic data collection was initiated in April 2006 (T1) or 9 months after the reform had been implemented, and 18 months later in October 2007 (T2). For this ethnographic research, we administered semi-structured interview protocols tailored to executives, service providers, and support staff at T1 (N=190) and T2 (N=177). We used a purposive sampling approach to ensure that participants had experience with issues of primary interest (Cresswell & Plano Clar, 2006). In each agency, we first interviewed an executive administrator who then referred service providers and support staff for participation. The interview protocols included several questions concerning cultural competency, inquiring into: perceived differences between the linguistic and cultural groups served by agencies; services provided to these groups; non-Western counseling and healing services; participant understanding of “culturally competent” or “culturally appropriate” services; the focus on CCS under the reform; and recent training received in CCS.

A total of 1,200 direct observation hours of the activities of clinical and support staff occurred on site at agencies for both waves of data collection. The observations augmented the interview material, enhancing insight into the overall work lives of providers, as well as individual- and agency-level factors bearing upon implementation of CCS. In particular, we participated in psychosocial rehabilitation programs, attended therapeutic support groups, and observed daily operations in agency reception areas and offices. Resulting data consisted of descriptive and inferential information, as ethnographers were encouraged to record perceptions and interpretations of people and events observed.

Field notes and interview recordings were transcribed into an electronic database for analysis. We coded the data using NVivo software (Bazeley, 2007). When analyzing interviews, we used a descriptive coding scheme based on the interview questions. When analyzing data from observations, we first used open coding to locate themes. We then used focused coding to determine which themes emerged frequently and which represented particular concerns (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 1995). Discrepancies in coding and analysis were resolved through consensus during regular team meetings (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003).

RESULTS

Survey Component

Impact on organizational supports for CCS

Table 2 reports changes in select CCS promoted under the reform between T1 and T2: (1) language access services; (2) training of clinical and support staff; and (3) completion of organizational self-assessments. Additionally, we present in Table 3 the agency ratings, provided by respondent CEOs and clinical directors, regarding the success of the reform in improving CCS.

Table 2.

Distribution of Agency-Level Cultural Competency Attributes, Time 1(T1) & Time2(T2)

| N | Neither T1 nor T2 | Both T1 & T2 | Only T1 | Only T2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language access services & organizational supports | ||||||

| Clinical staff spoke Spanish | 51 | 15.7% | 70.6% | 3.9% | 9.8% | .45 |

| Support staff spoke Spanish | 50 | 18.0% | 70.0% | 6.0% | 6.0% | .99 |

| Any materials in Spanish | 44 | 4.5% | 93.2% | 2.3% | 0% | .99 |

| Clinical staff spoke NAL | 49 | 53.1% | 22.4% | 6.1% | 18.4% | .15 |

| Support staff spoke NAL | 48 | 58.3% | 20.8% | 12.5% | 8.3% | .75 |

| Any materials in NAL | 39 | 76.9% | 5.1% | 10.3% | 7.7% | .99 |

| Required cultural competency training | ||||||

| Clinical staff | 51 | 13.7% | 64.7% | 11.8% | 9.8% | .99 |

| Support staff | 51 | 33.3% | 41.2% | 9.8% | 15.7% | .58 |

| Organizational cultural competency self-assessment | ||||||

| Agency conducted cultural competency self-assessment | 46 | 37.0% | 26.1% | 21.7% | 15.2% | .63 |

Note. NAL = Native American Languages.

Table 3.

Rating VONM Achievement of Increased Culturally Appropriate Services, Time 1 & Time 2

| N | Mean | SD | SE | 90% CI Lower | 90% CI Upper | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | 37 | 1.81 | .877 | .144 | ||||

| Time 2 | 37 | 2.19 | .877 | .144 | ||||

| Paired differences t test | 37 | 0.38 | 1.063 | .175 | .083 | .674 | 2.165 | .037 |

Note. VONM = ValueOptions New Mexico; SD = Standard deviation; SE = Standard error.

Language access services

No statistically significant changes related to language access services occurred between T1 and T2. Approximately 75–80% of agencies employed clinical and support staff that spoke Spanish at T1 and T2. The percentage of agencies offering services from clinical staff who spoke Native American languages increased from 28.5% to 40.8%, (p=.146). Approximately 30% of agencies employed support staff who spoke Native American languages.

Cultural competency training

No statistically significant changes were found in the percentage of agencies that required clinical or support staff to complete training in CCS. At both time points, approximately three-quarters of agencies required clinical staff to receive training in CCS and about half of agencies required such training for support staff.

Organizational self-assessment

There was no statistically significant change in the percentage of agencies that conducted an organizational self-assessment. About half of agencies undertook organizational self-assessments in T1 and T2.

Impact of VONM on CCS

As shown in Table 3, on a scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent), agencies reported a significant average increase between T1 (1.81) and T2 (2.19) in their assessments of how well VONM had worked to improve the availability of CCS (p=.037).

Document Review Component

Document review revealed that in the first three years, VONM personnel did not create a directory of providers with cultural competency capacity or evaluate either their own progress or that of agencies in addressing cultural competency. One possible explanation for this situation is that VONM did not have an agency liaison in place at the start of the reform, and experienced subsequent turnover that led the position to be vacant for months during the study period.

In Fiscal Year (FY) 2007, the state expanded the CCS requirements for VONM to include quarterly progress reports, annual updates of the cultural competency plan, and creation of a workgroup to advance CCS (Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative, 2007).

Claims data indicated that in the third year of the reform, approximately 4.8 percent of VONM members who self-identified as Native American received at least one traditional counseling service (ValueOptions, 2008). The impact of the reform on this service could not be assessed because the tracking of relevant claims only began in FY 2008, rather than at the start of the reform. Financial incentives for these services did not appear to support expansion. For example, with the exception of residential facilities that could incorporate traditional counseling into a bundled rate, agencies were paid a fixed rate of $30 per unit for traditional counseling sessions lasting one hour (e.g., talking circles, cultural mentorship, and spiritual coordination). However, the fee schedule reimbursed providers more than twice as much for one hour of comparable individualized Western services (e.g., $115 for group therapy, $75 for skills training and $64 for comprehensive community support) (Johnson & Charton, 2008).

Ethnographic Component

The ethnographic analyses identified the following five broad findings concerning CCS between T1 and T2: (1) inadequate resources, technical assistance, and training for CCS; (2) increased paperwork under reform shifted agency attention from CCS; (3) CCS disadvantaged in managed care environment; (4) limited views of and capacity for linguistically appropriate services; and (5) a lack of appreciation for CCS in professional care-giving contexts. In this discussion, quotes exemplifying each theme have been edited to enhance readability.

Inadequate resources, technical assistance, and training for CCS

Agency executives and providers reported that the state government and VONM had largely focused on introducing new administrative procedures under the reform, rather than expanding and improving CCS within the behavioral healthcare arena. Agency personnel at VONM were also provided with inadequate financial resources, which limited the scope of the CCS initiatives they could feasibly undertake. Few providers benefited from interactions with the agency liaison for cultural diversity or were even aware that such staff existed.

A slight increase in provider participation in CCS training occurred in the first three years of reform, compared to the year prior to reform (38% vs. 28%). At T2, providers from only a few of the participating agencies had attended CCS trainings sponsored by their employer, the state government, or VONM. The providers generally obtained training in CCS independently at their own expense. One provider complained that clinical staff at her agency had been mandated to participate in CCS training without pay.

Although availability was limited, some providers believed that their work and agency would benefit from CCS training. In the words of one provider (T1), “There’s a dangerous likelihood that clinicians don’t know what they don’t know. It’s ignorance without even an awareness level of being ignorant.” Other providers and support staff failed to appreciate the need for CCS training, because they had been raised in NM or shared the same ethnic background as clients and thus could draw upon a reservoir of “life experience.” Clients, in other words, could take heart that providers of like ethnic background “knew where they’re coming from.” For agency executives and providers, CCS training was less of a concern for persons of color than for White staff. Referring to her coworkers, one White provider (T2) noted, “It may not be necessary here to have Latino culturally-oriented training, because we have Latinos on staff, and we also interact with clients enough that I think that we know what their needs are…”

Increased paperwork under reform shifted agency attention from CCS

The transition to a single statewide delivery system created excessive paperwork demands within understaffed agencies. Beginning in June 2006, which coincided with T1, the state and its corporate partner required that providers enter extensive client eligibility and enrollment information into a Web-based data management system. Providers typically entered client data into this system, including demographic and diagnostic information. Providers expressed concerns that they had less time to spend with clients as a result of this requirement. By T2, it had become a commonplace practice for providers to complete client-related paperwork on their office computers during actual therapeutic sessions, cutting into clinical service provision for an estimated 15 minutes. Moreover, some providers did not view CCS as a realistic goal in their clinical encounters. One provider stated that he lacked the luxury of “getting to really know patients and listen to them talk a lot of about themselves.” He remarked, “I would love to have the time to provide culturally competent care. I’m all for it, but the question is how? How does that happen and who pays for it?”

During both T1 and T2, executives and providers were particularly concerned about obtaining payment for services because of claims processing problems at VONM. Working in settings under mounting fiscal pressure, executives and providers had to devote additional time to completing the extensive enrollment requirements (which were continually evolving), submitting claims, and tracking unpaid claims, and therefore had less time to address CCS, which, in turn, was generally characterized as a secondary priority within agencies.

CCS disadvantaged in managed care environment

Providers, particularly those working in medically pluralistic settings, commonly reported that they were unsure what types of culturally relevant services were billable under the reform and frequently critiqued their interactions with VONM utilization reviewers. One provider (T2) stated,

Three things challenge us [in providing CCS]—attitude, which carries over to sensitivity and awareness; knowledge that resources [culturally relevant services] are available and that healing isn’t done just by one method; and money—allowing the people that are delivering [culturally relevant] services here to have a time to learn [how to bill]…

Such concerns were particularly pronounced among providers who worked with Native American clients. These providers observed that the utilization review protocols of VONM favored Western medicine, and were insensitive to Native American etiologies, diagnoses, and healing modalities (Schneider, 2005). According to providers, VONM utilization reviewers were not well-versed in service practices associated with non-Western medicine, which led to problems securing authorizations. As a second provider (T2) described:

…You can’t actually access [the] money, because nobody understands [how to]…. If there was one thing that could beneficially come out of this thing [reform], it would be like, “Okay, here’s a directory of codes, and these [services] would be on this list….” Make it accessible enough that when we sit there and say, “Okay look, this is so and so who wants this [culturally relevant] service…and this is the billing code for it.

When accessible, reimbursement rates for culturally relevant services, such as sweat lodges and traditional ceremonies, did not fully cover costs for material and preparation time. We also did not find any agencies billing for promotora outreach related behavioral healthcare.

Limited views of and capacity for linguistically appropriate services

Most agency personnel maintained a partial understanding of CCS, associating CCS with the capacity to interact in non-English languages. For example, when asked how she understood CCS, one provider (T2) replied, “[Creating] a therapeutic environment that meets the needs of the different cultures. For instance, we have Spanish-speaking therapists who can provide therapy in their own language.” Although federal civil rights law required agencies to provide linguistically appropriate care, neither the state nor VONM provided separate or enhanced payment for such services. While our participants prided their agencies for posting signs in such languages, typically in Spanish and Diné, and cited these signs as an indicator of cultural competence, their ability to provide services in non-English languages was actually quite limited. Although all but two agencies consistently employed at least one bilingual clinician, who received the same salary as their monolingual counterparts, the demand for this individual’s services often overwhelmed the capacity. Despite frequent assertions that CCS was contingent on linguistically appropriate care, providers oftentimes relied upon untrained and non-reimbursed support staff or a client’s family member with “on-the-spot” interpretation. This long-standing practice raised problems in terms of quality, confidentiality, and provider-client rapport (Willging et al., 2008).

A lack of appreciation for CCS in professional care-giving contexts

Providers were generally supportive of the idea of CCS, although most did not consider cultural competence to be the driving force of clinical practice. They often minimized the importance of cultural issues in the work setting, claiming to “treat everybody the same” regardless of race or ethnicity. While emphasizing their attempts to “respect” all clients, providers still tended to stereotype the cultural beliefs and behaviors of members of specific social groups. Identified practices to promote CCS typically consisted of superficial acknowledgements, such as agency-sponsored culturally relevant holiday celebrations, or maintaining specific social postures based on stereotypes when interacting with clients. One provider (T2) explained, “We observe dress, mannerisms, eye contact or the avoidance thereof as being an example…. We do it on such a personal level that 90% of the populous doesn’t even realize we’re doing anything different.”

Some providers went one step further, facilitating access to services that were not based on Western models of therapy, a common practice within the four agencies that had large Native American clienteles. One provider (T1) stated, “We get a lot of Native Americans here from the pueblos and reservations…. A lot of them want to do their traditional praying. We provide cornmeal. They can go out and pray in the morning, however they want.” These providers also referred clients for Native American healing services. Such referrals were typically made upon client request. However, we also interviewed providers who took the initiative to offer to connect clients to these services in instances when they perceived clients as afraid to request them. In most cases, providers supplied the client with the name and phone number of a Native American healer, although some would set up the appointments if necessary. Two of the 14 participating agencies provided these services on site, including cedar and tobacco prayers, sweat lodge ceremonies, and talking circles. However, these services do not reflect changes due to the NM reforms as they were already offered to clients prior to the reform initiative. A third site had received external funding to sponsor events featuring curanderismo to raise local support for culturally-based healing modalities for Latinos within the surrounding communities. These events were advertised on reform-related email listservs, and thus benefited from increased publicity. Nevertheless, they were organized independently of the reform.

A minority of providers recognized that CCS required them to become knowledgeable about a client’s social milieu, cultural history, and worldview, and to understand that professional services were largely created within a “White” or “Anglo” frame of reference. Echoing the sentiments of his colleagues, one provider argued that agency leadership and staff lacked the initiative to promote CCS, asserting that more concerted efforts were needed to learn about cultural issues pertinent to service delivery at the levels of the individual and organization. He stated, “[We need to] listen, have our ears open, and find out how to find out.” By T2, only 4 of the 14 agencies had undertaken organizational self-assessments. Executives from these agencies viewed the assessments as useful endeavors that broadened staff perspectives on CCS.

DISCUSSION

This longitudinal, mixed-method study clarifies the minimal effect of the NM reform on the statewide capacity of agencies to deliver CCS to adults with SMI and the quality of these services. The ethnographic component’s in-depth focus on agency staff perspectives helps explain the lack of progress observed in the survey data. A comparison of survey responses between T1 and T2 indicated little to no increase in availability of either language access services or organizational supports. Though agencies were significantly more likely to report that the reform had contributed to increased CCS at T2, the improvement just barely raised the average rating from “poor” to “fair.” Overall, our ethnographic research found only a modest increase in provider understandings and practices related to CCS between T1 and T2. Although we observed a small increase in exposure to training during T2, sources other than the state government or VONM typically funded participation in these activities.

In terms of our conceptual model (see Figure 1), the ethnographic component elucidated key factors in external and internal environments of agencies that impeded improvement in CCS under the reform. First, low-level effort on the part of the state government, VONM, and community-based agencies to champion CCS contributed to the overall lack of improvement. Because an agency’s structure, activities, and guiding philosophies are shaped in part by the values, beliefs, and funding requirements within its external environment (Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978), meaningful and equitable financial and technical support for CCS from the state government and VONM would have increased the likelihood of adoption. Second, executives and providers commonly called attention to the reform’s increased requirements for intake, billing, reimbursement, and workload expectations. These requirements exacerbated the challenges of nurturing CCS by minimizing the time and financial resources available to deliver largely non-reimbursable services. Thus, not only did the external environment not promote CCS within agencies, but the new requirements actually decreased support and available resources for CCS. Third, insufficient appreciation for CCS among many staff in these agencies emerged as an important barrier that will likely require creative strategies to overcome. Training and promotional efforts under the reform were unsuccessful in convincing many providers to commit themselves to culturally competent practice or agency executives to expend organizational resources on CCS.

The extent to which the dominant belief systems within agencies are compatible with the targeted change is a critical internal factor that explains the extent to which innovation is adopted within practice settings (Rogers, 1995). Because executive leadership and other influential staff shape these beliefs (Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006), the effects of policy reforms could be strengthened through focused initiatives to increase support for CCS among high-ranking personnel.

Recommendations for Policy and Training

Examination of our findings within the context of CLAS suggests that agencies in NM were minimally successful at meeting certain expectations in the early years of reform. These expectations centered on availability of language assistance services (e.g., provision of bilingual staff and interpreter services), and displays of signage in the languages of clients and common groups in surrounding communities. Limited financial resources and technical support for CCS could not offset the reform’s increased administrative burden, which made adherence to other standards challenging. We did not observe much progress toward meeting these standards during this period. We offer several recommendations to improve system change focused on CCS.

First, CCS priorities should center on the mandatory CLAS standards related to language. All agencies in the ethnographic component had insufficient capacity to provide language appropriate clinical services. The survey revealed that Spanish speakers frequently lacked access to the same written materials available to English speakers. Both components identified ample room for improvement in terms of: (1) informing all limited English speakers of their right to no-cost language assistance; (2) ensuring access to competent language assistance at all points of contact; and (3) offering written materials for common non-English language groups. (It is important to note, however, that written materials in Native American languages may not be appropriate, as the majority of fluent speakers tend to be familiar only with the oral form.)

This study underscores the importance of providing sufficient resources to implement new policies and programs successfully. This is especially important when policies and programs are likely to impact ethnic minorities, who already experience disparate care in the public sector. Thus, for our second recommendation, we argue that the state government and its single managed care contractor must increase financial resources and technical support for community-based agencies to create an external environment that contributes to adoption and facilitates ongoing support of CCS within these agencies. Despite NM’s diversity in language and culture, agencies were often unable to adequately address these issues within the constraints of the current payment system. Studies of healthcare delivery have documented the effectiveness of increased payment for expanding the availability of targeted services (Isett et al., 2007). New Mexico can improve the alignment of financial incentives to encourage CCS provision by: (1) including interpretation as a billable service; and (2) creating an enhanced rate for clinical treatment delivered in non-English languages (American College of Mental Health Administration, 2003). Currently, agencies that deliver CCS, except for traditional counseling, must squeeze dollars to pay for such services indirectly from payment rates for other services.

In addition, non-Western services should be reimbursed at comparable rates to individual therapy. This suggestion is consistent with recent recommendations emphasizing the view that genuinely culturally competent care includes non-Western services that are provided by highly (albeit differently) trained providers (Goodkind et al., 2011).

Third, we recommend that the state require agencies to conduct regular organizational self-assessments of CCS. These reviews are an effective method for increasing staff awareness of the need for comprehensive CCS at all levels (Goode, Jones, & Mason, 2002). A self-assessment is an essential first step for any agency undertaking initiatives to improve CCS and can play a critical role in creating supportive internal environments (Siegel, Haugland, & Chambers, 2003).

Fourth, key stakeholders at the state, agency, and professional association level would do well to collaborate on new CCS training requirements that challenge the perceptions of frontline workers that culture exerts negligible impact on clinical work, and on clients’ illnesses, use of services, and adherence to treatment (Beach et al., 2005). Voluntary training opportunities for clinicians and support staff will be ineffective in reaching those who would benefit most from education due to overestimation of their cultural competence or failure to appreciate the relevance of CCS for clients (Yamada & Brekke, 2008). Revised training requirements could expand the number of continuing education hours and include demonstrations of how greater cultural awareness improves client retention and outcomes (Bhui, Warfa, Edonya, McKenzie, & Bhugra, 2007). It is not enough to stress the importance of CCS in healthcare. Providers must also remain mindful of their cultural biases and how these biases can affect client interactions, while better preparing them to address multiple dimensions of CCS delivery. Providers who understand the importance of CCS and demonstrate meaningful practices related to CCS should be recognized, rewarded, and encouraged to share this expertise with their colleagues.

Limitations

This mixed-method study focused only on agencies serving adults with SMI, excluding the perspectives of independent practitioners and primary care providers who deliver a limited set of behavioral health services (e.g., medication management and individual therapy). Nor did we consider CCS as it relates to non-ethnic minority populations, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people (Willging, Salvador, & Kano, 2006). The ethnographic component only included 14 agencies, which could further limit generalizability. Despite our high response rate in the survey component, the sample size limited our capacity to identify small or potentially even moderate effects as statistically significant. Finally, this research occurred in NM and therefore some aspects of it may not generalize to other states.

CONCLUSION

In 2005, NM embarked upon an ambitious reform of publicly-funded behavioral healthcare with the goal of improving CCS in this majority-minority state. The reform resulted in little improvement in CCS capacity as demonstrated in a comparison of statewide surveys. The ethnographic work identified several systemic barriers to enhanced CCS capacity, particularly the reported bias against CCS practices in utilization review and payment and the increased fiscal and time pressures of managed care requirements. New Mexico and other states seeking to enhance CCS should consider ways to increase support within external environments, i.e., offering financial incentives to improve the fiscal bottom line for agencies offering these services. Organizational self-assessments represent a potential approach for increasing the support within agencies’ internal environments by raising staff awareness of the need for CCS.

Acknowledgments

Grant Number MH076084

Footnotes

For the purposes of NIHMS submission the Principal Investigator of the study is Cathleen E. Willging, Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, 612 Encino Place NE, Albuquerque, NM 87102. 505-765-2328, cwillging@pire.org. She should be the approving author for this submission.

References

- Aarons GA, Sawitzky AC. Organizational culture and climate and mental health provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Psychological Services. 2006;3:61–72. doi: 10.1037/1541-1559.3.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Sommerfeld D, Willging CE. The soft underbelly of system change: The role of leadership and organizational climate in turnover during statewide behavioral health reform. Psychological Services. 2011;8:269–281. doi: 10.1037/a002619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Mental Health Administration. Financing results and value in behavioral health services. Albuquerque, NM: American College of Mental Health Administration; 2003. Retrieved from http://www.acmha.org/content/reports/FinancingPaperFinal5-16-03.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bazeley P. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, Robinson KA, Gozu A, Palacio A, Cooper LA. Cultural competence: A systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Medical Care. 2005;43:356–373. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156861.58905.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhui K, Warfa N, Edonya P, McKenzie K, Bhugra D. Cultural competence in mental health care: A review of model evaluations. BMC Health Services Research. 2007;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CI, Alexander JA. Culturally competent treatment practices and ancillary service use in outpatient substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow JC, Jaffee K, Snowden L. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:792–797. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell JW, Plano Clar VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson RM, Fretz RI, Shaw LL. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Goode T, Jones W, Mason J. A guide to planning and implementing cultural competence organizational assessment. Washington DC: National Center for Cultural Competence; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind JR, Ross-Toledo K, John S, Hall JL, Ross L, Freeland L, Lee C. Rebuilding TRUST: A community, multi-agency, state, and university partnership to improve behavioral health care for American Indian youth, their families, and communities. Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;39:452–477. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DL. Culturally competent treatment of African American clients among a national sample of outpatient substance abuse treatment units. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24:89–102. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde PS. State mental health policy: A unique approach to designing a comprehensive behavioral health system in New Mexico. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:983–985. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative. Statewide behavioral health services contract. Santa Fe, NM: State of New Mexico; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative. Statewide behavioral health services contract. Santa Fe, NM: State of New Mexico; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Isett KR, Burnam MA, Coleman-Beattie B, Hyde PS, Morrissey JP, Magnabosco J, Goldman HH. The state policy context of implementation issues for evidence-based practices in mental health. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:914–921. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.7.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B, Charton S. Consumers served and expenditures by service. Albuquerque, NM: ValueOptions New Mexico®; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly JR, Renshaw LR, Schwartz JS, Hillman AL, Pauly MV, Teplensky JD. Rethinking Organizational Change. In: West MA, Farr JI, editors. Innovation and Creativity at Work: Psychological and Organizational Strategies. New York, NY: Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lieu TA, Finkelstein JA, Lozano P, Capra AM, Chi FW, Jensvold N, Farber HJ. Cultural competence policies and other predictors of asthma care quality for Medicaid-insured children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e102–e110. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JW, Rowan B. Institutional organizations: formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology. 1977;83:363. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Lagomasino I, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB. Improving care for minorities: Can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Services Research. 2003;38:613–630. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning & National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. Cultural competency: Measurement as a strategy for moving knowledge into practice in state mental health systems. Alexandria, VA: National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning and the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achieving the promise: transforming mental health care in America - Final report (SMA-03-3832) Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Minority Health. National standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care (Final Report) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Opler LA, Ramirez PM, Mougious VM. Outcome Measurement in Serious Mental Illness. In: Ishak WW, Burt T, Sederer LI, editors. Outcome Measurement in Psychiatry: A Critical Review. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2002. p. 466. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer J, Salancik GR. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. New York, NY: Harper & Row; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 4. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Writing the proposal for a qualitative research methodology project. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13:781–820. doi: 10.1177/1049732303013006003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A. Reforming American Indian/Alaska Native health care financing: The role of Medicaid. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:766–768. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.061317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semansky RM, Altschul D, Sommerfeld D, Hough R, Willging CE. Capacity for delivering culturally competent mental health services in New Mexico: Results of a statewide agency survey. Administration and Policy in Mental Health Services Research. 2009;36:289–307. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0221-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semansky RM, Hodgkin D, Willging CE. Preparing for a public sector mental health reform in New Mexico: The experience of agencies serving adults with serious mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, Online First. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9418-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel C, Haugland G, Chambers ED. Performance measures and their benchmarks for assessing organizational cultural competency in behavioral health care service delivery. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2003;31:141–170. doi: 10.1023/b:apih.0000003019.97009.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG. Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Language and English-Language Ability: 2000. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce; 2003. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-29.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. United States and Puerto Rico-GCT-P6. Race and Hispanic or Latino: 2000. 2011 Retrieved from: http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/GCTTable?bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-_box_head_nbr=GCT-P6&-ds_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U&-format=US-9.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity-A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General (SMA-01-3613) Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- ValueOptions New Mexico. DRLC-01 Consumers Served and Expenditures by Service FY08 Fourth Quarter. Albuquerque, NM: ValueOptions New Mexico; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vandervort EB, Melkus GD. Linguistic services in ambulatory clinics. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2003;14:358–366. doi: 10.1177/1043659603257338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook JI, Braithwaite J, Georgiou A, Ampt A, Creswick N, Coiera E, Iedema R. Multimethod evaluation of information and communication technologies in health in the context of wicked problems and sociotechnical theory. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2007;14:746–755. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willging CE, Salvador M, Kano M. Unequal treatment: Mental health care for sexual and gender minority groups in a rural state. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:867–870. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willging CE, Waitzkin H, Nicdao E. Medicaid managed care for mental health services: The survival of safety net institutions in rural settings. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18:1231–1246. doi: 10.1177/1049732308321742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada AM, Brekke JS. Addressing mental health disparities through clinical competence not just cultural competence: the need for assessment of sociocultural issues in the delivery of evidence-based psychosocial rehabilitation services. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1386–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziguras S, Klimidis S, Lewis J, Stuart G. Ethnic matching of clients and clinicians and use of mental health services by ethnic minority clients. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:535–541. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]