Abstract

Aims

Health Canada has developed a pathway to approve drugs that have limited efficacy and safety data, the Notice of Compliance with conditions (NOC/c) policy. Increased safety reporting is required for these drugs but there has not been any systematic review of their post-market safety. This study compares safety warnings for NOC/c drugs with drugs with a priority and a standard review.

Methods

A list of drugs approved between January 1 1998 and March 31 2013 was developed and serious safety warnings for these drugs were identified. Drugs were put into one of three groups based on the way that they were approved. Kaplan−Meier curves were generated to examine the likelihood of NOC/c drugs receiving a serious safety warning compared with drugs with a priority and a standard review. The time spent in the review process for each of the groups was also measured.

Results

Compared with drugs with a priority review, NOC/c drugs were not more likely to receive a serious safety warning (P = 0.5940) but were more likely than drugs with a standard review (P = 0.0113). NOC/c drugs spent less time in the review process compared with drugs with a standard review.

Conclusions

Possible reasons for the increase likelihood of a serious safety warning are the limited knowledge of the safety of NOC/c drugs when they are approved and the length of time that they spend in the review process. Health Canada should consider spending longer reviewing these drugs and monitor their post-market safety more closely.

Keywords: Health Canada, new active substances, post-market safety warnings, priority review, standard review

What is Already Known about this Subject

Drugs approved in shorter periods of time are more likely to have post-market safety problems.

Drugs approved with limited efficacy and safety data by the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency are no more likely to have post-market safety problems than drugs approved through a standard review process.

What this Study Adds

In Canada drugs approved with limited safety and efficacy data are more likely to receive a serious safety warning compared with drugs approved through a standard review process.

The increased risk of receiving a safety warning may be because these drugs spend less time in the review process and because less safety data are available when they are reviewed.

Introduction

The usual pathway to get a new active substance (NAS – a molecule never marketed before in Canada in any form) approved for marketing in Canada is for the pharmaceutical company involved to file a New Drug Submission (NDS) including preclinical and clinical scientific information about the product's safety, efficacy and quality and information about its claimed therapeutic value, conditions for use and side effects 1. The key clinical evidence establishing the safety and efficacy of the new drug comes from the pivotal trials that Health Canada defines ‘as trials of high scientific quality, which provide the basic evidence to determine the efficacy, properties and conditions of use of the drug’ 2. Health Canada then has up to 300 days to review the NDS and make a decision about whether or not to approve the drug or in the parlance of the agency issue a Notice of Compliance (NOC).

In an effort to ensure that promising therapies for serious illnesses can reach Canadians in a timely manner Health Canada has developed two other pathways for approving NAS. The first of these is the priority review of drug submissions intended ‘for a serious, life-threatening or severely debilitating disease or condition for which there is substantial evidence of clinical effectiveness that the drug provides … effective treatment, prevention or diagnosis of a disease or condition for which no drug is presently marketed in Canada or … a significant increase in efficacy and/or significant decrease in risk such that the overall benefit/risk profile is improved over existing therapies, preventatives or diagnostic agents for a disease or condition that is not adequately managed by a drug marketed in Canada’ 3. The company seeking approval still has to submit a complete NDS but the review period is reduced to 180 days.

The second mechanism is the Notice of Compliance with conditions (NOC/c). The goal of this policy is to ‘provide patients suffering from serious, life threatening or severely debilitating diseases or conditions with earlier access to promising new drugs’ where surrogate markers suggest that these new products offer ‘effective treatment, prevention or diagnosis of a disease or condition for which no drug is presently marketed in Canada or significantly improved efficacy or significantly diminished risk over existing therapies’ 4. (In the case of cancer a surrogate outcome might be a shrinkage in tumour size or a longer time until the cancer recurs.) Besides data based only on trials with surrogate markers, other instances where a NOC/c might be used are for NAS with phase II trials that require confirmation with phase III trials or NAS with a single small to moderately sized phase III trial that requires confirmation of either the efficacy or safety of the agent under question 5. In return for NOC/c status, companies sign a Letter of Undertaking to complete confirmatory clinical studies, that is studies that definitively establish efficacy, and submit the results of these to Health Canada. Should these post-market trials not provide sufficient evidence of clinical benefit the NOC/c could be revoked and the product removed from the market 6. If companies apply for NOC/c status when they file the NDS and Health Canada agrees to the NOC/c application then drugs are reviewed in 200 days. If companies do not initially apply for NOC/c status then drugs are reviewed in either 180 or 300 days and Health Canada may grant NOC/c status at the end of the review.

Previous work has found that a NAS that receives a priority review (180 days) has a 34.2% (95% CI 24.3, 44.2) chance of acquiring a serious safety warning and/or being withdrawn compared with a 19.8% (95% CI 14.8, 24.8) chance if it is reviewed in 300 days (P < 0.0005) 7. This difference was not attributable to the mechanism of action of the drug or due to the indication for the drug, leading to the conclusion that the reason was the shorter review period.

Health Canada acknowledges that safety information about drugs approved under the NOC/c policy may be limited as more safety reporting for these products is generally required in the form of patient registries, or Periodic Safety Update Reports 8. To date there has not been any review of the post-market safety of this group of drugs. The purpose of this study is to examine the chance that a drug approved under this policy will receive a serious safety warning or be withdrawn from the market and to compare NOC/c drugs with those that received a priority review and those that received a standard review. The a priori null hypothesis is that despite the limited amount of safety information available for NOC/c drugs their chance of receiving a serious safety warning or being withdrawn from the market will be the same compared with the other two groups of drugs.

Methods

A list of NAS approved from the start of the policy on January 1 1998 until March 31 2013 was compiled from the annual reports of the Therapeutic Products Directorate (TPD) and the Biologics and Genetic Therapies Directorate (BGTD) (henceforth collectively referred to as the TPD), available by directly contacting the directorates at <publications@hc-sc.gc.ca>. For each product the following information was abstracted: generic name, brand name, indication, date of application for a NOC or NOC/c, date of NOC and basis for approval – standard or priority review or NOC/c. Health Canada can issue a NOC/c for either a NAS or for a new indication for an existing product. For the purpose of this study only NAS were analyzed because there will be more known about the safety of drugs that are already on the market and then receive a NOC/c for a new indication. If a NAS received a NOC/c for more than one indication only the first indication was used.

Safety warnings and drug withdrawals for the period January 1 1998 to December 31 2013 were identified through advisories for health professionals on the MedEffect Canada web site <http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/medeff/advisories-avis/prof/index-eng.php>. For each safety advisory or notice of withdrawal of a product, the date and reason were recorded. All serious safety advisories (those using bolded black print or boxed warnings) were included except for those dealing with the withdrawal of a specific batch or lot number due to manufacturing problems or those issued because of misuse of a drug (e.g. an unapproved use) or medication errors (e.g. a warning about remembering to remove a transdermal patch before applying a second one).

Since there may be a trade off between a significant increase in therapeutic value and safety, the therapeutic value of NOC/c drugs was assessed using the ratings from the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) and the French drug bulletin Prescrire International. Both of these organizations evaluate drugs once they have been approved for marketing. The PMPRB is a federal agency that is responsible for calculating the maximum introductory price for all new patented medications introduced into the Canadian market. As part of the process of determining the price, its Human Drug Advisory Panel (HDAP) determines the therapeutic value of each product it reviews 9. For the purpose of this study, products that were deemed breakthrough and substantial improvement were termed ‘significant therapeutic advance’ and products in other groups were termed ‘no therapeutic advance’. In some cases the PMPRB annual reports indicated that the therapeutic value of the product was still being determined and in those cases the PMPRB was contacted directly to determine the final classification.

If the PMPRB had not considered a product then its therapeutic value was determined from Prescrire evaluations (available at: http://english.prescrire.org/en/). Prescrire rates products using the following categories: bravo (major therapeutic innovation in an area where previously no treatment was available), a real advance (important therapeutic innovation but has limitations), offers an advantage (some value but does not fundamentally change the present therapeutic practice), possibly helpful (minimal additional value and should not change prescribing habits except in rare circumstances), nothing new (may be new molecule but is superfluous because does not add to clinical possibilities offered by previously available products), not acceptable (without evident benefit but with potential or real disadvantages) and judgment reserved (decision postponed until better data and more thorough evaluation). The first three Prescrire categories were defined as a significant therapeutic advance and the other Prescrire categories (except judgment reserved) were defined as no therapeutic advance. Previous work has shown a moderate level of agreement between the therapeutic evaluations from the PMPRB and Prescrire 10.

Kaplan−Meier survival curves were separately calculated for the period from receipt of NOC or NOC/c until a first safety warning for the following comparisons: a) drugs approved with a NOC/c vs. approval through a priority review and b) drugs approved with a NOC/c vs. approval through a standard review and the curves were compared using a log rank (Mantel−Cox) test. A Kaplan−Meier analysis accounts for the fact that some NAS had received a safety warning and some had not by the end of the study period (March 31 2013). The times between the application for a NOC or NOC/c and receipt of one and the time between receipt of a NOC or NOC/c and a safety warning and/or withdrawal from the market were calculated in days. If a drug received more than one serious safety warning only the time to the first warning was used. Medians are reported for both time periods as these values are not normally distributed (Shapiro−Wilk test) and were compared using the Mann−Whitney test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant. There were no power calculations as the entire population of NAS was evaluated rather than just a sample. Calculations were done using Excel 2011 for Macintosh (Microsoft) and Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software).

Results

There were a total of 378 NAS approved in the period under study. Twenty-seven received a NOC/c, 86 had a priority review and 265 a standard review (see Appendix 1 for a complete list of the drugs and their review status). Eleven of the 27 (40.7%, 95% CI 28.9, 52.8) with a NOC/c received a safety warning only 9 or were withdrawn because of safety concerns 2. The corresponding numbers for drugs with a priority and standard review were 24 (23 with safety warnings only and one withdrawn) (27.9%, 95% CI 18.9, 36.9) and 50 (38 with safety warnings only and 12 withdrawn) (18.9%, 95% CI 12.9, 24.9), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Drugs approved through Notice of Compliance with conditions vs. those approved through a priority and standard review

| Approval based on | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| NOC/c* | Priority review | Standard review | |

| Total number NAS† | 27 | 86 | 265 |

| Number (%) with serious safety warning and/or withdrawn from market for safety reason | 11 (40.7) | 24 (27.9) | 50 (18.9) |

| Number withdrawn from market with prior safety warning | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Number withdrawn from market without prior safety warning | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Median time (interquartile range) from application for NOC§ or NOC/c to approval (days) | 332 (274, 480) | 235 (212, 487)¶ | 398 (349, 618)** |

| Median time (interquartile range) from NOC or NOC/c to first serious safety warning or withdrawal from market (days) | 1614 (858, 1704) | 944 (536, 1429)†† | 1159 (637, 1583)‡‡ |

NOC/c = Notice of compliance with conditions.

NAS = New active substance.

NOC = Notice of compliance. ¶Compared with NOC/c, Mann−Whitney, P = 0.0757.

Compared with NOC/c, Mann−Whitney, P = 0.0124.

Compared with NOC/c, Mann−Whitney, P = 0.1265.

Compared with NOC/c, Mann−Whitney, P = 0.2486.

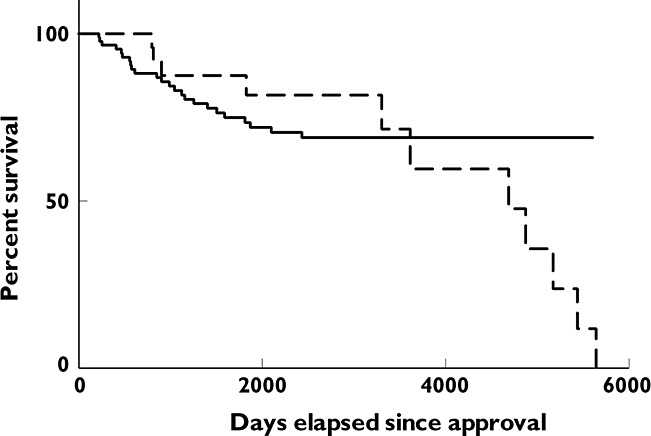

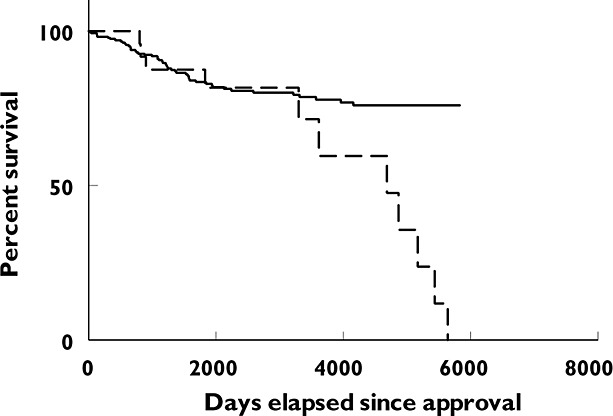

Figure 1 shows the Kaplan−Meier curves for the time from approval to the first serious safety warning and/or removal from the market for drugs with an approval through a NOC/c vs. those approved after a priority review. The curves indicate the proportion that did not have a safety warning. There is no statistically significant difference in the curves for the two groups of products (P = 0.5940, log rank (Mantel−Cox) test). Figure 2 presents the same information for drugs approved through a NOC/c vs. those approved after a standard review. In this case there is a statistically significant difference between the two curves (P = 0.0113, log rank (Mantel−Cox) test).

Figure 1.

Kaplan−Meier curve showing time to first serious safety warning or removal from market for new active substances: approval through NOC/c vs. priority review.  , NOC/c;

, NOC/c;  , priority review. No significant difference between curves, P = 0.5940, log rank (Mantel−Cox) test

, priority review. No significant difference between curves, P = 0.5940, log rank (Mantel−Cox) test

Figure 2.

Kaplan−Meier curve showing time to first serious safety warning or removal from market for new active substances: approval through NOC/c vs. standard review.  , NOC/c;

, NOC/c;  , standard review. Curves significantly different, P = 0.0113, log rank (Mantel−Cox) test

, standard review. Curves significantly different, P = 0.0113, log rank (Mantel−Cox) test

The date on which an application for a NOC or NOC/c was filed was only available for drugs approved from January 1 2005 onwards. The median time from application for a NOC or NOC/c to approval was 332 days (interquartile range 274−480) for drugs with a NOC/c, 228 days (interquartile range 213−484) for those with a priority review and 398 days (interquartile range 349−618) for those with a standard review. There was no significant difference in review times between drugs with a NOC/c and those with a priority review (Mann−Whitney, P = 0.0757) but there was for the comparison of drugs with a NOC/c and those with a standard review (Mann−Whitney, P = 0.0124) (Table 1).

The time from receipt of a NOC or NOC/c to when Health Canada issued a first safety warning for the product or the product was removed from the market was 1614 days (interquartile range 858−1704) for drugs with a NOC/c, 944 days (interquartile range 536−1429) for those with a priority review and 1159 (637−1583) for those with a standard review. There was no significant difference in time to a safety warning between drugs with a NOC/c and those with a priority review (Mann−Whitney, P = 0.1265) or those with a standard review (Mann−Whitney, P = 0.2486).

Ten of the 27 NOC/c drugs were for cancer, six for HIV/AIDS, three for various haematological disorders and one each for acute graft vs. host disease, Alzheimer disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, congestive heart failure, cystic fibrosis, Fabry disease, Friedreich's ataxia and influenza. The PMPRB evaluated the therapeutic value of 24 out of 27 of the drugs with a NOC/c and rated 19 as no therapeutic advance. One of the remaining three was rated as no therapeutic advance by Prescrire and neither organization assessed the other two (see Appendix 2 for a list of the indications and therapeutic evaluations of the drugs).

Discussion

Compared with drugs approved after a standard review, drugs approved through a NOC/c were significantly more likely to receive a serious safety warning and/or be removed from the market, whereas post-market safety as measured by receipt of a safety warning and/or removal from the market was the same for NOC/c drugs and those with a priority review. Therefore, the null hypothesis is rejected when it comes to the former comparison but not the latter. The greater likelihood of safety problems for NOC/c drugs may be due to two factors – the limited amount of safety data when they are approved and their shorter review time. An examination of drugs approved through a similar pathway, the accelerated approval process, used by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), has found that the median number of patients in the intervention group is only half the number in the intervention group for drugs that had a standard review 11. This statistically significant smaller number of patients could account for the relative paucity of safety information. The findings from this study also raise the question of whether Health Canada is adequately monitoring the safety of NOC/c drugs once they are marketed.

Given that 20 out of 25 NOC/c drugs were not rated as significant therapeutic advances, the increased safety risk with these drugs does not appear to be balanced by greater therapeutic value. The finding that there is no difference in the time taken to identify a safety issue for NOC/c drugs and those with a standard review can be seen as troubling as safety problems in drugs with a greater risk are not being identified earlier in their post-market phase.

The FDA accelerated approval process allows a drug for serious conditions that fills an unmet medical need to be approved based on a surrogate end point. As with the NOC/c policy, companies are required to conduct post-market studies to verify the clinical benefit 12. The safety of oncology drugs approved under the accelerated approval process has been evaluated in two studies. Berlin looked at how often label revisions were made for oncology products approved between the start of 1992 and the end of 2006 under both accelerated approval and the standard approval process. The rate of revisions for accelerated products was approximately two times that of traditional products 13. Richey and colleagues reviewed drugs approved through accelerated approval and the regular approval pathway between 1995 and 2008 and found no difference in safety between the two groups 14. The difference between these two studies may be because Berlin looked at all labelling changes including those about efficacy 13. The difference between this study and the two American ones may be because they focused only on oncology products whereas drugs for cancer were only 37% (10/27) of the NOC/c drugs. It is also possible that the FDA does a better job of identifying safety issues in drugs that enter the accelerated approval pathway.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has also adopted two pathways to get drugs through the approval system more rapidly, conditional approval (CA) and approval under exceptional circumstances (EC). The former is similar to the NOC/c policy whereby drugs are approved based on less comprehensive data than that required for standard applications but show a demonstrated positive benefit–risk balance and there is an expectation of more data in the near future via post-market studies 15. Approval under exceptional circumstances is granted where the ‘indications for which the product in question is intended are encountered so rarely that the applicant cannot reasonably be expected to provide comprehensive evidence, or in the present state of scientific knowledge, comprehensive information cannot be provided, or it would be contrary to generally accepted principles of medical ethics to collect such information’ 16. Two studies have compared drugs approved under a combination of the CA and EC procedures with those approved under the standard procedure and neither found an increased risk of safety problems with the CA and EC drugs 17,18. The difference between this study and the European ones may be that the EC drugs are used so rarely that safety problems are harder to detect. Also the EMA might do a better job of detecting safety issues in the premarket phase.

This study has a number of limitations. The definition of a serious safety warning was based on the way that Health Canada displayed the information (bolded black print and/or boxed text) but the criteria that Health Canada used to develop its safety warnings and the emphasis that it placed on any particular safety issue are extremely vague. One Health Canada document states ‘Regulatory actions … are taken according to the regulatory framework in place. This implies an evaluation of the signal and the appropriate benefit−risk review of the information available’ 19. The date on which a NAS receives a NOC is not necessarily the date on which the company actually decides to market the drug and therefore the length of time the drug is available before it receives a safety warning may be shorter than what is reported here. The time NAS spent in the approval process could only be calculated for drugs approved after January 1 2005. It wa not possible to determine whether there were differences in the number of people who were potentially harmed by the safety problems that triggered the safety warnings for the various drugs. Similarly, all safety warnings were treated as equivalent regardless of the possible number of people affected or potentially affected or the nature of the safety issue. It is also important to note that the regulatory decision to issue a safety warning should not be equated with the actual degree of harm caused by the drug. Finally, there is the question of whether the assessment of therapeutic advance from the HDAP and Prescrire is more likely to be accurate compared with the assessment that Health Canada makes. However, Health Canada makes its decision based solely on the premarket clinical trials whereas HDAP's (and Prescrire's) decision is made after approval when more information about the product is available.

Drugs that can treat serious and previously untreatable diseases should be provided as soon as possible to patients but not at the expense of potentially harming them. Health Canada should reconsider the amount of safety data that it requires for drugs approved through the NOC/c process and closely monitor these drugs once they are marketed.

Competing Interests

I have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare no support from any organization for the submitted work and no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years. In the previous 3 years I have been the chair of the board of Health Action International – Europe.

Appendix 1

All new active substances approved between January 1 1998 and March 31 2013 and review status

| Generic name | Brand name | Review status (NOC/c, priority, standard) |

|---|---|---|

| Abacavir | Ziagen | NOC/c |

| Abatacept | Orencia | Priority |

| Abiraterone | Zytiga | Priority |

| Acamprosate | Campral | Standard |

| Adalimumab | Humira | Standard |

| Adefovir | Hepsera | Priority |

| Afluzosin | Xatral | Standard |

| Agalsidase alfa | Replagal | NOC/c |

| Agalsidase beta | Fabrazyme | Priority |

| Alatrofloxacin | Trovan (IV) | Standard |

| Alefacept | Amevive | Standard |

| Alemtuzumab | Mabcampath | Standard |

| Alglucosidase alfa | Myozyme | Priority |

| Aliskiren | Rasilez | Standard |

| Alitretinoin | Toctino | Standard |

| Alitretinoin | Panretin | Standard |

| Almotriptan | Axert | Standard |

| Ambrisentan | Volibris | Standard |

| Aminolevulinic acid | Levulan | Standard |

| Amlexanox | Apthera | Standard |

| Amprenavir | Agenerase | NOC/c |

| Anakinra | Kineret | Priority |

| Ancestim | Stemgen | Standard |

| Anidulafungin | Eraxis | Standard |

| Anti-thymocyte globulin | Thymoglobulin | Standard |

| Apixaban | Eliquis | Standard |

| Aprepitant | Emend | Standard |

| Argatroban | Argatroban | Priority |

| Aripiprazole | Abilify | Standard |

| Atazanavir | Reyataz | Priority |

| Atomoxetine | Strattera | Standard |

| Axitinib | Inlyta | Standard |

| Azacitidine | Vidaza | Priority |

| Azilsartan | Edarbi | Standard |

| Aztreonam for inhalation solution | Cayston | NOC/c |

| Basiliximab | Simulect | Priority |

| Becaplermin gel | Regranex | Standard |

| Belimumab | Benlysta | Standard |

| Bendamustine | Treanda | Standard |

| Besifloxacin | Besivance | Standard |

| Bevacizumab | Avastin | Priority |

| Bicistate | OncoScint | Standard |

| Bimatoprost | Lumigan | Standard |

| Bivalirudin | Angiomax | Standard |

| Boceprevir | Victrelis | Priority |

| Boceprevir, perinterferon alfa-2b, ribavirin | Victrelis Triple | Priority |

| Bortezomib | Velcade | NOC/c |

| Bosentan | Tracleer | Priority |

| Botulinum toxin type B | Myobloc | Standard |

| Brinzolamide | Azopt ophthalmic suspension | Standard |

| Bupropion | Wellbutrin SR | Standard |

| Cabazitaxel | Jevtana | Standard |

| Cabergoline | Dostinex | Standard |

| Canakinumab | Ilaris | Priority |

| Candesartan | Atacand | Standard |

| Capecitabine | Xeloda | Priority |

| Capsular polysaccharide | Synflorix | Standard |

| Caspofungin | Cancidas | Priority |

| Catridecacog | Tretten | Priority |

| Cefdinir | Omnicef | Standard |

| Ceftobiprole | Zeftera | Standard |

| Celecoxib | Celebrex | Priority |

| Cerivastatin | Baycol | Standard |

| Certolizumab pegol | Cimzia | Standard |

| Cetrorelix | Cetrotide | Standard |

| Cetuximab | Erbitux | Priority |

| Choriogonadotropin alfa | Ovidrel | Standard |

| Ciclesonide | Alvesco | Standard |

| Cidofovir | Vistide | Standard |

| Cinacalcet | Sensipar | Priority |

| Citalopram | Celexa | Standard |

| Clevidipine | Cleviprex | Standard |

| Clofarabine | Clolar | Standard |

| Clopidogrel | Plavix | Standard |

| Colesevelam | Lodalis | Standard |

| Collagenase clostridium histolyticum | Xiaflex | Standard |

| Crizotinib | Xalkori | NOC/c |

| Dabigatran | Pradax | Standard |

| Daclizumab | Zenaprax | Priority |

| Dadolinium (III) | Gadolite | Standard |

| Dalfopristin | Synercid | Standard |

| Daptomycin | Cubicin | Standard |

| Darbepoetin alpha | Aranesp | Standard |

| Darifenacin | Enablex | Standard |

| Darunavir | Prezista | Standard |

| Dasatinib | Sprycel | NOC/c |

| Deferasirox | Exjade | NOC/c |

| Degarelix | Firmagon | Standard |

| Delavirdine | Rescriptor | NOC/c |

| Denosumab | Prolia | Standard |

| Desloratadine | Aerius | Standard |

| Desvenlafaxine | Pristiq | Standard |

| Dexlansoprazole | Dexilant | Standard |

| Dexmedetomidine | Precedex | Standard |

| Dextromethylphenidate | Attenade | Standard |

| Dienogest | Visanne | Standard |

| Docosanol | Abreva | Standard |

| Doripenem | Doribax | Standard |

| Doxercalciferol | Hectorol | Standard |

| Doxycycline | Efracea | Standard |

| Dronedarone | Multaq | Priority |

| Drospirenone | Yasmin 21/28 | Standard |

| Drotrecogin alfa | Xigris | Standard |

| Dulasteride | Avodart | Standard |

| Duloxetine | Cymbalta | Standard |

| Eculizumab | Soliris | Priority |

| Efalizumab | Raptiva | Standard |

| Efavirenz | Sustiva | Priority |

| Eflornithine | Vaniqa | Standard |

| Eletriptan | Relpax | Standard |

| Eltrombopag | Revolade | Standard |

| Elvitgravir, emtricitabine, tenofovir, cobicistat | Stribild | Standard |

| Emedastine | Emadine ophthalmic solution | Standard |

| Emtricitabine | Emtriva | Standard |

| Enfuvirtide | Fuzeon | Priority |

| Entacapone | Comtan | Standard |

| Entecavir | Baraclude | Priority |

| Eplerenone | Inspra | Standard |

| Eprosartan | Teveten | Standard |

| Eptifibade | Integrilin | Standard |

| Eribulin | Halaven | Standard |

| Erlotinib | Tarceva | Priority |

| Ertapenem | Invanz | Standard |

| Escitalopram | Cipralex | Standard |

| Esomeprazole | Nexium | Standard |

| Etanercept | Enbrel | Priority |

| Ethinyl estradiol/etonogestrel | Nuvaring | Standard |

| Etravirine | Intelence | Priority |

| Everolimus | Afinitor | Standard |

| Exemestane | Aromasin | Standard |

| Exenatide | Byetta | Standard |

| Ezetimibe | Ezetrol | Standard |

| Ezogabine | Potiga | Standard |

| F-Fluorodeoxyglucose | Cantrace | Priority |

| Fampridine | Fampyra | Standard |

| Febuxostat | Uloric | Standard |

| Ferumoxytol | Feraheme | Standard |

| Fesoterodine | Toviaz | Standard |

| Fidaxomicin | Dificid | Standard |

| Fingolimod | Gilenya | Standard |

| Fluticasone | Avamys | Standard |

| Fomepizole | Antizol | Priority |

| Fondaparinux | Arixtra | Priority |

| Fosamprenavir | Telzir | Standard |

| Fosaprepitant | Emend IV | Standard |

| Fosfomycin | Monurol | Standard |

| Frovatriptan | Frova | Standard |

| Fulvestrant | Faslodex | Standard |

| Gadobenate | Multihance | Standard |

| Gadobutrol | Gadovist | Standard |

| Gadofosveset | Vasovist | Standard |

| Gadoversetamide | Optimark | Standard |

| Gadoxetate | Primovist | Standard |

| Galantamine | Reminyl | Standard |

| Ganirelix | Orgalutran | Standard |

| Gatifloxacin | Tequin | Standard |

| Gefitinib | Iressa | NOC/c |

| Gemifloxacin | Factive | Standard |

| Glimepiride | Amaryl | Standard |

| Glucagon, rDNA origin | Glucagon | Standard |

| Golimumab | Simponi | Standard |

| Grepafloxacin | Raxar | Standard |

| Hetastarch | Hextend | Standard |

| Histrelin | Vantas | Standard |

| Human C1 esterase inhibitor | Berinert | Standard |

| Ibritumomab | Zevalin | Priority |

| Ibutilide | Corvert injection | Standard |

| Icodextrin | Extraneal | Standard |

| Idebenone | Catena | NOC/c |

| Idursulfase | Elaprase | Priority |

| Imatinib | Gleevec | NOC/c |

| Indacaterol | Onbrez breezhaler | Standard |

| Infliximab | Remicade | Standard |

| Infliximab | Remicade | Priority |

| Influenza vaccine | Flumist | Standard |

| Insulin detemir | Levemir | Standard |

| Insulin glulisine | Apidra | Standard |

| Interferon beta-1A | Rebif | Standard |

| Ioxilan | Oxilan | Standard |

| Ipilimumab | Yervoy | Standard |

| Irbesartan | Avapro | Standard |

| Iron | Venofer | Priority |

| Ivacaftor | Kalydeco | Priority |

| Japanese encephalitis vaccine | Ixiaro | Standard |

| Lacosamide | Vimpat | Standard |

| Lanreotide | Somatuline autogel | Standard |

| Lanthanum | Fosrenol | Standard |

| Lapatinib | Tykerb | Standard |

| Laronidase | Aldurazyme | Priority |

| Leflunomide | Arava | Standard |

| Lenalidomide | Revlimid | NOC/c |

| Levetiracetam | Keppra | Standard |

| Levobupivacaine | Chirocaine | Standard |

| Lexidronam | Quadramet | Standard |

| Linagliptin | Trajenta | Standard |

| Linezolid | Zyvoxam | Standard |

| Lipoprotein-ospA antigen recombinant | Lymerix | Priority |

| Liraglutide | Victoza - 1.2 mg pen-injector | Standard |

| Lisdexamfetamine | Vyvanse | Standard |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | Kaletra | Priority |

| Loteprednol | Alrex | Standard |

| Lumiracoxib | Prexige | Standard |

| Lurasidone | Latuda | Standard |

| Lutropin Alfa | Luveris | Standard |

| Mangafodipir | Teslascan | Standard |

| Maraviroc | Celsentri | Priority |

| Melanoma theraccine | Melacine | Priority |

| Meloxicam | Mobic | Standard |

| Memantine | Ebixa | NOC/c |

| Meningococcal group C polysaccharide, tetanus toxoid | Neisvac-C | Priority |

| Meningococcal oligosaccharides conjugated | Menveo | Standard |

| Mequinol/tretinoin | Solage | Standard |

| Methacoline | Methacoline | Standard |

| Methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta | Mircera | Standard |

| Methyl aminolevulinate | Metvix | Standard |

| Methylnaltrexone | Relistor | Priority |

| Micafungin | Mycamine | Standard |

| Miglitol | Glyset | Standard |

| Miglustat | Zavesca | Priority |

| Mirtazapine | Remeron | Standard |

| Modafinil | Alertec | Standard |

| Montelukast | Singulair | Standard |

| Moroctocog alpha | Refacto | Priority |

| Moxifloxacin | Avelox | Standard |

| Naratriptan | Amerge | Standard |

| Natalizumab | Tysabri | Priority |

| Nateglinide | Starlix | Standard |

| Nebivolol | Bystolic | Standard |

| Nelarabine | Atriance | NOC/c |

| Nelfinavir | Viracept | Standard |

| Nepafenac | Nevanac | Standard |

| Nesiritide | Natrecor | NOC/c |

| Nevirapine | Viramune | NOC/c |

| Nilotinib | Tasigna | NOC/c |

| Nitric oxide | Inomax | Priority |

| Norelgestromin/ethinyl estradiol | Evra | Standard |

| Ofatumumab | Arzerra | Standard |

| Olmesartan | Olmetec | Standard |

| Omalizumab | Xolair | Standard |

| Orlistat | Xenical | Standard |

| Oseltamivir | Tamiflu | Priority |

| Oxaliplatin | Eloxatin | Priority |

| Oxcarbazepine | Trileptal | Standard |

| Palifermin | Kepivance | Priority |

| Paliperidone | Invega | Standard |

| Paliperidone | Invega sustenna | Standard |

| Palivizumab | Synagis | Standard |

| Palonosetron | Aloxi | Standard |

| Panitumumab | Vectibix | NOC/c |

| Pantoprazole | Pantaloc M | Standard |

| Paricalcitol | Zemplar | Standard |

| Pazopanib | Votrient | Standard |

| Pegaptanib | Macugen | Priority |

| Pegfilgrastim | Neulasta | Standard |

| Peginterferon alfa-2a | Pegasys | Standard |

| Peginterferon alfa-2a ribavirin | Pegasys RBV | Priority |

| Peginterferon alfa-2b | Peg-intron | Standard |

| Peginterferon alfa-2b ribavirin | Pegetron | Standard |

| Pegvisomant | Somavert | Priority |

| Pemetrexed | Alimta | Priority |

| Penciclovir | Denavir | Standard |

| Perindopril | Coversyl | Standard |

| Pimecrolimus | Elidel | Standard |

| Pioglitazone | Actos | Priority |

| Plerixafor | Mozobil | Standard |

| Pneumococcal conjugate | Prevnar | Priority |

| Posaconazole | Spriafil (Posanol) | Priority |

| Pramipexole | Mirapex | Standard |

| Prasugrel | Effient | Standard |

| Pregabalin | Lyrica | Standard |

| Prucalopride | Resotran | Standard |

| Rabeprazole | Pariet | Standard |

| Raloxifene | Evista | Standard |

| Raltegravir | Isentress | NOC/c |

| Ranibizumab | Lucentis | Priority |

| Rasagiline | Azilect | Standard |

| Rasburicase | Fasturtec | Priority |

| Recombinant cholera toxin B subunit | Dukoral | Priority |

| Recombinant factor VIIa | Niastase | NOC/c |

| Recombinant human papillomavirus | Cervarix | Standard |

| Recombinant human papillomavirus | Gardasil | Priority |

| Recombinant-methionyl interferon consensus 1 | Infergen | Priority |

| Remestemcel-L | Prochymal | NOC/c |

| Repaglinide | Gluconorm | Standard |

| Retapamulin | Altargo | Standard |

| Rilpivirine | Edurant | Standard |

| Riluzole | Rilutek | NOC/c |

| Risedronate | Actonel | Standard |

| Rituximab | Rituxan | Priority |

| Rivaroxaban | Xarelto | Standard |

| Rivastigmine | Exelon patch 10 | Standard |

| Rivastigmine | Exelon | Standard |

| Rizatriptan | Maxalt | Standard |

| Rofecoxib | Vioxx | Priority |

| Roflumilast | Daxas | Standard |

| Romiplostim | Nplate | Priority |

| Rosiglitazone | Avandia | Priority |

| Rosuvastatin | Crestor | Standard |

| Rotavirus vaccine | Rotarix | Standard |

| Rotaviruses | Rotateq | Standard |

| Rubidium chloride rb 82 | Ruby-fill | Priority |

| Rufinamide | Banzel | Standard |

| Ruxolitinib | Jakavia | Priority |

| Sapropterin | Kuvan | Priority |

| Saxagliptin | Onglyza | Standard |

| Senapine | Saphris | Standard |

| Sevelamer | Renvela | Standard |

| Sevelamer | Renagel | Standard |

| Sibutramine | Meridia | Standard |

| Sildenafil | Viagra | Standard |

| Silodosin | Rapaflo | Standard |

| Sirolimus | Rapamune | Standard |

| Sitaglipin | Januvia | Standard |

| Sitaxsentan | Thelin | Standard |

| Sodium oxybate | Xyrem | Standard |

| Solifenacin | Vesicare | Standard |

| Sorafenib | Nexavar | NOC/c |

| Stiripentol | Diacomit | Standard |

| Sulesomab | Leukoscan | Standard |

| Sulfur hexafluoride | Sonovue | Standard |

| Sunitnib | Sutent | NOC/c |

| Tadalafil | Cialis | Standard |

| Tamsulosin | Flomax | Standard |

| Tapentadol | Nucynta CR | Standard |

| Tegafur/uracil and leucovorin calcium | Orzel | Standard |

| Tegaserod | Zelnorm | Standard |

| Telaprevir | Incivek | Priority |

| Telavancin | Vibativ | Standard |

| Telbivudine | Sebivo | Priority |

| Telithromycin | Ketek | Standard |

| Telmisartan | Micardis | Standard |

| Temozolomide | Temodal | Standard |

| Temsirolimus | Torisel | Priority |

| Tenecteplase | Tnkase | Standard |

| Tenofovir | Viread | NOC/c |

| Teriparatide | Forteo | Priority |

| Thrombin alfa | Recothrom | Standard |

| Thyrotrophin | Thyrogen | Standard |

| Ticagrelor | Brilinta | Priority |

| Tigecycline | Tygacil | Standard |

| Tiotropium | Spiriva | Standard |

| Tipranavir | Aptivus | Priority |

| Tirofiban | Aggrastat | Standard |

| Tizanidine | Zanaflex | Standard |

| Tocilizumab | Actemra | Standard |

| Tolterodine | Detrol | Standard |

| Tolvaptan | Samsca | Standard |

| Toremifene | Fareston | Standard |

| Tositumomab | Bexxar | Priority |

| Trabectedin | Yondelis | Standard |

| Tramadol | Tramacet | Standard |

| Trastuzumab | Herceptin | Priority |

| Travoprost | Travatan | Standard |

| Treprostinil | Remodulin | Priority |

| Triptorelin | Trelstar | Standard |

| Trospium | Trosec | Standard |

| Trovafloxacin | Trovan (tablets) | Standard |

| Unoprostone isopropyl | Rescula | Standard |

| Ustekinumab | Stelara | Standard |

| Valdecoxib | Bextra | Standard |

| Valganciclovir | Valcyte | Standard |

| Valrubicin | Valstar | Priority |

| Vandetanib | Caprelsa | Standard |

| Vardenafil | Levitra | Standard |

| Varenicline | Champix | Standard |

| Varicella vaccine | Varivax | Standard |

| Varicella zoster vaccine | Varilrix | Priority |

| Velaglucerase alfa | VPRIV | Standard |

| Vemurafenib | Zelboraf | Priority |

| Verteporfin | Visudyne | Priority |

| Voriconazole | Vfend | Standard |

| Vorinostat | Zolinza | Standard |

| Yttrium-90 | Yttrium-90 | Priority |

| Zaleplon | Starnoc | Standard |

| Zanamivir | Relenza | NOC/c |

| Zoledronic acid | Zometa | Priority |

| Zolmitriptan | Zomig | Standard |

| Zucapsaicin | Civanex (Zuacta) | Standard |

Appendix 2

Drugs approved under Notice of Compliance with Conditions

| Therapeutic evaluation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic name | Brand name | Indication | Patented medicine prices review board | Prescrire international |

| Abacavir | Ziagen | HIV/AIDS | Not innovative | |

| Agalsidase alfa | Replagal | Fabry disease | Not innovative | |

| Amprenavir | Agenerase | HIV/AIDS | Innovative | |

| Aztreonam for inhalation solution | Cayston | cystic fibrosis | Not innovative | |

| Bortezomib | Velcade | multiple myeloma | Not innovative | |

| Crizotinib | Xalkori | lung cancer | Not innovative | |

| Dasatinib | Sprycel | chronic myeloid leukemia | Not evaluated | |

| Deferasirox | Exjade | thalassemia | Innovative | |

| Delavirdine | Rescriptor | HIV/AIDS | Not innovative | |

| Gefitinib | Iressa | lung cancer | Innovative | |

| Idebenone | Catena | Friedreich's ataxia | Not innovative | |

| Imatinib | Gleevec | gastrointestinal tumour | Not innovative | |

| Lenalidomide | Revlimid | anaemia due to myelodysplastic syndrome | Not innovative | |

| Memantine | Ebixa | Alzheimer disease | Not innovative | |

| Nelarabine | Atriance | leukemia | Not innovative | |

| Nesiritide | Natrecor | congestive heart failure | Not innovative | |

| Nevirapine | Viramune | HIV/AIDS | Not innovative | |

| Nilotinib | Tasigna | chronic myeloid leukemia | Not innovative | |

| Panitumumab | Vectibix | colorectal cancer | Not innovative | |

| Raltegravir | Isentress | HIV/AIDS | Innovative | |

| Recombinant factor VIIa | Niastase | clotting disorders | Not innovative | |

| Remestemcel-L | Prochymal | acute graft vs. host disease | Not evaluated | |

| Riluzole | Rilutek | amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | Not innovative | |

| Sorafenib | Nexavar | renal cancer | Not innovative | |

| Sunitnib | Sutent | renal cancer | Not innovative | |

| Tenofovir | Viread | HIV/AIDS | Not innovative | |

| Zanamivir | Relenza | influenza | Innovative | |

References

- Health Canada: Health Products and Food Branch. Access to Therapeutic Products: The Regulatory Process in Canada. Ottawa: Health Canada: Health Products and Food Branch; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Preparation of Human New Drug Submissions. Ottawa: Health Canada; 1991. . Available at http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2013/sc-hc/H42-2-38-1991-eng.pdf (last accessed 11 June 2014) [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada: Health Products and Food Branch. 2009. Guidance for industry: priority review of drug submissions.

- Health Canada. Notice of Compliance with Conditions (NOC/c) Ottawa: Health Canada; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Health Products and Food Branch. 2011. Guidance document: notice of compliance with conditions (NOC/c)

- Lexchin J. Notice of compliance with conditions: a policy in limbo. Healthc Policy. 2007;2:114–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lexchin J. New drugs and safety: what happened to new active substances approved in Canada between 1995 and 2010? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1680–1681. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M. The characteristics and fulfillment of conditional prescription drug approvals in Canada. Health Policy. 2014;116:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. 2014. Compendium of policies, guidelines and procedures – reissued June 2014. Available at http://www.pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca/view.asp?ccid=492 (last accessed 21 June 2014)

- Lexchin J. International comparison of assessments of drug innovation. Health Policy. 2012;105:221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing N, Aminawung J, Shah N, Krumholz H, Ross J. Clinical trial evidence supporting FDA approval of novel therapeutic agents, 2005–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:368–377. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Fast track, Breaktrhough Therapy, Accelerated Approval and Priority Review. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2014. . Available at http://www.fda.gov/ForPatients/Approvals/Fast/default.htm (last accessed 21 June 2014) [Google Scholar]

- Berlin RJ. Examination of the relationship between oncology drug labeling revision frequency and FDA product categorization. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1693–1698. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richey E, Lyons E, Nebeker J, Shankaran V, McKoy M, Luu T, Nonzee N, Trifilio S, Sartor O, Benson AB, III, Carson KR, Edwards BJ, Gilchrist-Scott D, Kuzel TM, Raisch DW, Tallman MS, West DP, Hirschfeld S, Grillo-Lopez AJ, Bennett CL. Accelerated approval of cancer drugs: improved access to therapeutic breakthroughs or early release of unsafe and ineffective drugs? J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4398–4405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission regulation (EC) no. 507/2006. Official J Eur Union. 2006;L:92/6–928. [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on Procedures for Granting of A Marketing Authorisation under Exceptional Circumstances, Persuant to Article 14 (8) of Regulation (EC) NO 726/2004. London: European Medicines Agency; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arnardottir A, Hasijer-Ruskamp F, Straus S, Eichler H-G, de Graeff P, Mol P. Additional safety risk to exceptionally approved drugs in Europe. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72:490–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon W, Moors E, Meijer A, Schellekens H. Conditional approval and approval under exceptional circumstances as regulatory instruments for stimulating responsible drug innovation in Europe. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:848–853. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marketed Health Products Directorate. How Adverse Reaction Information on Health Products Is Used. Ottawa: Marketed Health Products Directorate; 2004. [Google Scholar]