Abstract

Progression of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDCM) is marked with extensive left ventricular remodeling whose clinical manifestations and molecular basis are poorly understood. We aimed to evaluate the clinical potential of titin ligands in monitoring progression of cardiac remodeling associated with end-stage IDCM. Expression patterns of 8 mechanoptotic machinery-associated titin ligands (ANKRD1, ANKRD2, TRIM63, TRIM55, NBR1, MLP, FHL2, and TCAP) were quantitated in endomyocardial biopsies from 25 patients with advanced IDCM. When comparing NYHA disease stages, elevated ANKRD1 expression levels marked transition from NYHA < IV to NYHA IV. ANKRD1 expression levels closely correlated with systolic strain depression and short E wave deceleration time, as determined by echocardiography. On molecular level, myocardial ANKRD1 and serum adiponectin correlated with low BAX/BCL-2 ratios, indicative of antiapoptotic tissue propensity observed during the worsening of heart failure. ANKRD1 is a potential marker for cardiac remodeling and disease progression in IDCM. ANKRD1 expression correlated with reduced cardiac contractility and compliance. The association of ANKRD1 with antiapoptotic response suggests its role as myocyte survival factor during late stage heart disease, warranting further studies on ANKRD1 during end-stage heart failure.

1. Introduction

Despite intensive search for therapeutic interventions, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDCM) remains the major cause of heart failure eventually leading to heart transplantation. Limited availability of donor hearts results in long waiting times before transplantation can be performed. Many patients with end-stage heart failure perish before a donor heart becomes available. Management of patients awaiting transplantation is demanding, because some of them remain stable while others deteriorate quickly [1]. However, transplantation specialists do not have reliable tools to differentiate between these two disease courses. Therefore, there is a pressing need for markers predicting the prognosis and disease course of end-stage heart failure caused by IDCM in order to prioritize patient listing for transplantation.

Myocyte apoptosis was shown to be a contributor to the development of heart failure (HF) [2], whereas experimental studies on mouse models have suggested that this process might at least be mediated trough the titin filament and its ligands [3]. However, this hypothesis has not been tested so far in clinical settings. Here, we have evaluated expression levels of 8 titin ligands in endomyocardial biopsies (EMB). Differences in ANKRD1 expression pattern were found to be most informative: ANKRD1 levels were associated with decreased cardiac contractility and compliance. ANKRD1 gene encodes an ankyrin repeat-domain containing protein 1 (Ankrd1, known as well as CARP-cardiac ankyrin repeat protein). Ankrd1 belongs to a family muscle ankyrin repeat proteins, interacting with titin in a stretch-dependent manner: upon mechanical stretch it translocates to the nucleus, where it acts as transcription cofactor [4]. Ventricular ANKRD1 upregulation was observed in increased stretch states such as experimental pressure overload [5] or clinical heart failure due to dilated [6] and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy [7]. Moreover, mutations in ANKRD1 were found to be associated with dilated [8] and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [9]. Functionally, myocardial ANKRD1 acts as an antiapoptotic survival factor after ischemia-reperfusion injury [10] and hypoxia [11] and is downregulated in apoptosis-driven [12, 13] anthracycline cardiomyopathy [14]. In this work, we present data indicating that ANKRD1 together with adiponectin might act as myocyte survival factors, associated with antiapoptotic response in the terminal stage of IDCM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

Our study cohort was composed of patients admitted to the Vilnius University Hospital during 2011–2013 with suspected diagnosis of IDCM. All patients underwent a careful history and physical examination, as well as routine laboratory studies, including B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), adiponectin, and cardiac troponin T (hsTnT). 23 patients were selected because of a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF < 45%) in the absence of significant coronary artery disease (stenosis of coronary arteries of less than 50%), a history of myocardial infarction, and other specific heart muscle diseases (primary valvular heart disease, toxic cardiomyopathy, arterial hypertension, renal failure, and abuse of alcohol or illicit drugs), all consistent with primary IDCM. IDCM diagnosis was confirmed by histological analysis of endomyocardial biopsies (EMB). Patients who were diagnosed as having acute myocarditis according to histological evidence were excluded from the present study. NYHA class was assigned by a clinician unaware of patient echocardiographic investigation. All patients received maximal pharmacological heart failure therapy according to European Society of Cardiology guidelines: ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptors blockers, β-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptors blockers, digitalis (in case of atrial fibrillation), diuretics, anticoagulant (in case of atrial fibrillation, EF < 40%), and antiarrhythmics (class III: amiodarone) (see Supplementary Table 1 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/273936). Clinical decision about possible treatment with cardiac resynchronization therapy, radiofrequency ablation, or implantation of a left ventricular assist device or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator was made after coronary angiography and EMB. All patients gave written informed consent to this study, including cardiac catheterisation and EMB. The study was approved by Lithuanian Bioethics Committee (Protocol number 158200-2011/09) and conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Echocardiography and Cardiac Catheterisation

Echocardiographic evaluation was performed 1 day before cardiac catheterisation by GE Vivid 7 and 9 ultrasound system by an investigator blinded for the study objectives. The standard LV apical (apical 4, apical 2, and apical 3) views and parasternal short axis views at mid-papillary level were acquired at 70–90 frames/s. Conventional echocardiographic parameters such as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular end-diastolic dimension (LVEDD), left ventricular end-systolic dimension (LVESD), velocities of E and A waves (E and A) and their ratio (E/A), and E deceleration time (DcT) were obtained. All images were stored digitally for subsequent offline analysis. Quantification of myocardial deformation values was performed by 2D speckle tracking using Echopac PCBT08 (GE Healthcare) software. After the manual selection, speckles were assumed automatically and then confirmed by the investigator. By the semiautomatic postprocessing longitudinal (in 4 chamber-4C, two-chamber-2C, and three chamber-3C views), circumferential, and radial strain (RS) and strain rate parameters were extracted. Mean pulmonary artery (PA) pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) were measured and EMB was taken during right heart catheterization. Biopsy specimens were immediately placed to −70°C until further processing.

2.3. Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA from EMB samples was extracted using RNeasy fibrous tissue minikit according to provided protocol (Qiagen). Tissue was directly homogenized in lysis buffer using Ultra-Turrax device. RNA was reverse transcribed using High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit primed with mixture of random and poly-dT primers (Invitrogen). Transcripts were quantified using TaqMan Gene Expression assay on Real-Time Stratagene MX 3005P machine following manufacturer recommendations. Amplification efficiency validated TaqMan probes (Supplementary Table 2) used in this work are presented in Table 2. 18S rRNA was used for standardization. As this study did not contain a reference group and was based on individual EMB samples, C t method could not be used for quantification of transcript levels. Therefore relative transcript abundances were quantified using C t method (C t gene of interest − C t S18 rRNA). Transcript levels in this work are expressed as negative C t values; thus higher −C t values denote higher mRNA levels whereas negative C t values represent genes that are less abundant compared with the reference gene. Bax/Bcl-2 ratios were calculated as C t((C t Bax − C t S18 rRNA)−(C t Bcl-2 − C t S18 rRNA)) corresponding to relative expression ratio [15].

Table 2.

Differences in myocardial expression patterns of titin ligands according to NYHA functional class <IV (n = 19) and NYHA IV (n = 6).

| Transcript level (−ΔC t) | NYHA class | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| <IV | IV | ||

| ANKRD1∗ | −9.42 ± 0.7 | −6.83 ± 0.7 | 0.01 |

| ANKRD2∗ | −16.79 ± 0.7 | −14.5 ± 0.8 | 0.03 |

| TRIM63∗ | −13.81 ± 0.6 | −11.82 ± 0.5 | 0.03 |

| TRIM55 | −14.23 ± 0.8 | −13.11 ± 0.7 | 0.25 |

| NBR1 | −11.97 ± 0.7 | −11.73 ± 0.9 | 0.44 |

| MLP | −10.39 ± 1.0 | −9.15 ± 0.9 | 0.20 |

| FHL2 | −10.07 ± 0.8 | −9.75 ± 0.6 | 0.56 |

| TCAP | −7.08 ± 0.9 | −6.16 ± 0.8 | 0.30 |

| BCL-2∗ | −17.81 ± 0.4 | −16.25 ± 0.7 | 0.02 |

| BAX | −15.71 ± 0.3 | −14.39 ± 0.9 | 0.22 |

Significant differences (P value < 0.05 of the Mann-Whitney U test) marked with ∗.

2.4. Measurement of Activated Caspase-3

Levels of activated caspase-3 in EMB samples were determined using ELISA, specific for the activated protein form (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). Tissue samples were lysed by sonification in RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific Inc., USA) supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors according to manufacturer's recommendations (Thermo Scientific Inc., USA). Protein content in clarified lysates was measured using modified Lowry protein assay using bovine serum albumin as standard according to the provided protocol (Thermo Scientific Inc., USA). Analyte concentration was expressed as ng/mg of total protein.

2.5. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17 software. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess differences between two independent groups. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was used to evaluate linear dependence between values. If otherwise not indicated, a value of P < 0.05 was taken as significant (two-tailed).

3. Results

3.1. Induction of the Titin Ligands ANKRD1, ANKRD2, and TRIM63 in Patients with End-Stage IDCM in Correlation with NYHA Staging

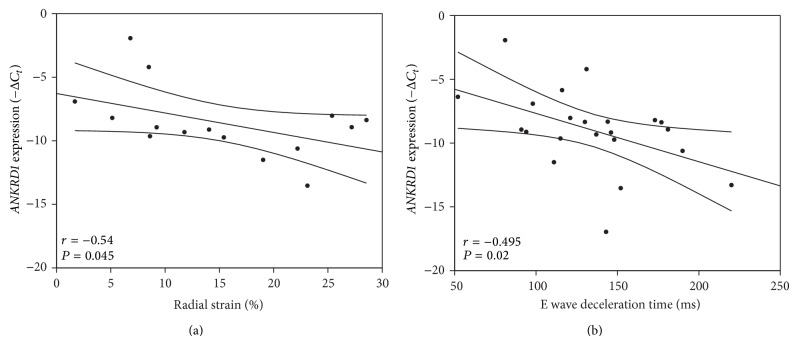

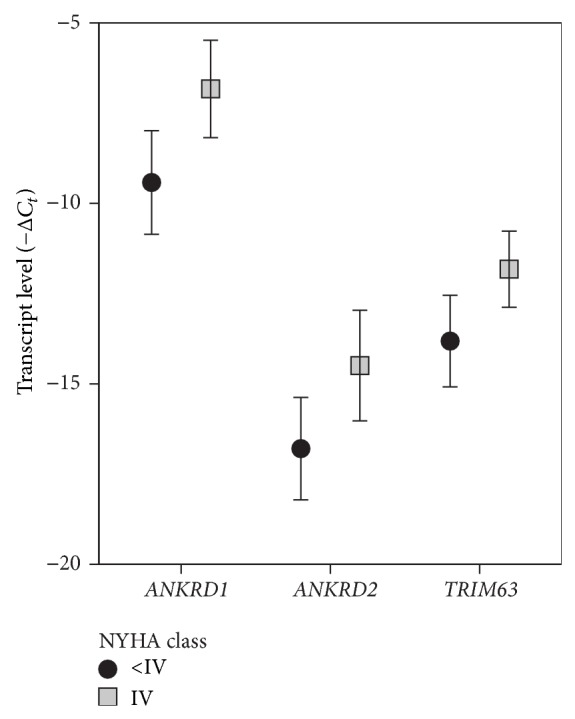

Here, we determined the transcript levels of ANKRD1, ANKRD2, TRIM63, TRIM55, NBR1, MLP, FHL2, and TCAP in EMB biopsies from end-stage IDCM patient cohort to test their potential roles in titin-based cellular stress transmission. Clinically, we surveyed patients with significantly reduced LVEF, elevated BNP and TnT values, elevated intracardiac pressures, and impaired relaxation (Table 1). Patients were divided into two groups according to the severity of HF symptoms based on NYHA functional class: Group IV (symptomatically Severe HF) and Group <IV (mainly class III; symptomatically moderate HF), and the expression levels of mechanoptotic machinery members were compared (Table 2). Out of 8 studied transcripts, ANKRD1, ANKRD2, and TRIM63 were significantly higher in NYHA class IV than <IV NYHA class group (Figure 1, P = 0.01 for ANKRD1 and P = 0.03 for ANKRD2 and TRIM63). ANKRD1 had the highest expression levels compared to other titin ligands and the most profound 6-fold induction (calculated as 2Ct IV NYHA−Ct<IV NYHA) in NYHA IV patients as compared to NYHA <IV patients. Therefore, ANKRD1 expression pattern was the most sensitive to the disease progression and was chosen for the further analysis.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| NYHA class | ||

|---|---|---|

| <IV | IV | |

| Age (years) | 44.2 ± 14.2 | 43.5 ± 13.9 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 4 | 1 |

| Male | 15 | 5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.7 ± 4.7 | 28.7 ± 5.1 |

| NYHA class | ||

| II | 1 | |

| III | 16 | |

| III-IV | 2 | |

| IV | 6 | |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 1259 ± 1180 | 1964 ± 1177 |

| TnT (pg/mL) | 80.9 ± 143.5 | 34.4 ± 13.9 |

| Adiponectin (μg/mL) | 22.9 ± 12.6 | 33.8 ± 17.5 |

| LVEF (%) | 24.1 ± 7.4 | 20.1 ± 6.2 |

| LVESD (mm) | 58.2 ± 9.9 | 64.3 ± 10.2 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 67.3 ± 7.4 | 71.1 ± 12 |

| RAP (mmHg) | 12.5 ± 7.3 | 16.2 ± 11 |

| PAP (mmHg) | 32.2 ± 12.1 | 43.2 ± 15.8 |

| PCWP (mmHg) | 23 ± 9.1 | 31.8 ± 14.2 |

| PVR (Wood units) | 2.5 ± 1.7 | 3.2 ± 0.8 |

| E wave (m/s) | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1 ± 0.3 |

| A wave (m/s) | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| E/A | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 0.4 |

| E wave T dec (ms) | 140.1 ± 35.2 | 109 ± 45.4 |

Figure 1.

Myocardial titin ligand expression patterns associate with disease progression in IDCM patients. Statistically significant titin ligand expression differences represented as bar graph. Data are presented as mean ± 2 s.e.m. Note the highest expression level and the most pronounced difference between groups in ANKRD1 expression pattern.

3.2. ANKRD1 Expression Correlates with LV Remodeling in End-Stage IDCM Patients

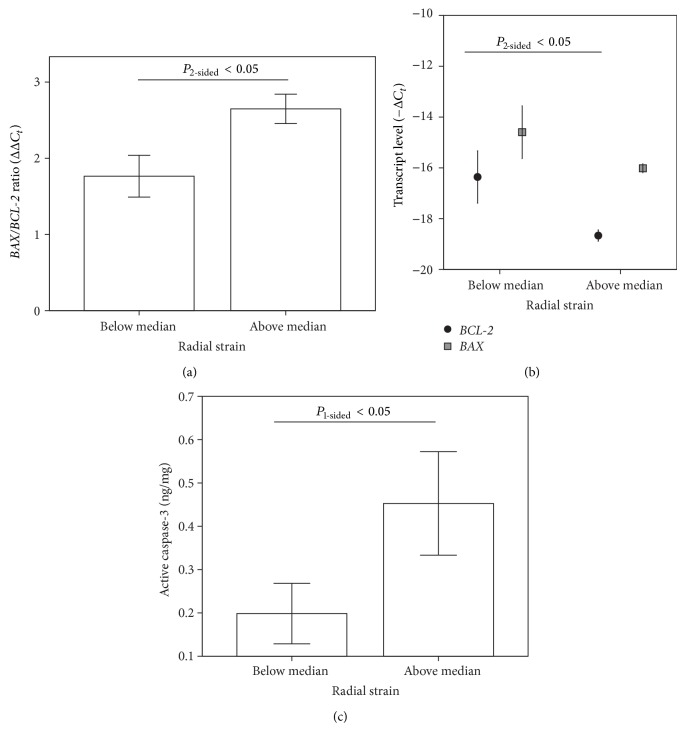

In order to investigate clinical correlates of ANKRD1 expression we looked for further clinical parameters different between NYHA class >IV and <IV. Statistically significant differences between NYHA <IV and NYHA IV groups were only detected for parameters of systolic strain (Table 3). Strain measurements quantify magnitudes and velocities of myocardial deformation estimating myocardial contractility [16]. Radial and longitudinal strain in 3C projection showed marked reduction in severe HF patients (NYHA IV) when compared to symptomatically moderate HF patients (NYHA <IV) (Table 3). Correlation analysis confirmed that reduced cardiac contractility correlated with ANKRD1 expression independently from NYHA functional class (Figure 2(a)). Further, we found that ANKRD1 expression correlated with the E wave deceleration time shortening, which is an index for LV stiffness [17] (Figure 2(b)). Taken together, ANKRD1 expression is associated with LV remodeling resulting in reduced cardiac contractility and compliance.

Table 3.

Differences in strain parameters between NYHA <IV and NYHA IV groups.

| Strain parameter | NYHA class | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| <IV | IV | ||

| 4C strain (%) | −7.4 ± 1 | −4 ± 0.8 | 0.10 |

| 4C strain rate (s−1) | −0.4 ± 0 | −0.2 ± 0 | 0.10 |

| 2C strain (%) | −6.7 ± 0.9 | −5.1 ± 0.9 | 0.25 |

| 2C strain rate (s−1) | −0.3 ± 0 | −0.3 ± 0 | 0.34 |

| 3C strain (%)∗ | −8.1 ± 0.8 | −3.9 ± 1.1 | 0.01 |

| 3C strain rate (s−1) | −0.8 ± 0.4 | −0.2 ± 0 | 0.11 |

| Circumferential strain (%) | −5.5 ± 0.5 | −4.3 ± 1.2 | 0.51 |

| Circumferential strain rate (s−1) | −0.4 ± 0 | −0.2 ± 0 | 0.20 |

| Radial strain (%)∗ | 17.4 ± 2.3 | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 0.01 |

| Radial strain rate (s−1) | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.11 |

Note further reduction of systolic strain parameters along disease progression.

Significant differences (P value < 0.05 of the Mann-Whitney U test) marked with ∗.

Figure 2.

Increased ANKRD1 expression marks left ventricular remodeling. (a) Linear correlation between ANKRD1 expression and radial stain. Regression line is represented within 95% confidence interval for the mean value. A negative correlation between ANKRD1 expression (−C t) and radial strain (RS; %) was found (n = 14, r = −0.54, P < 0.05). (b) Linear correlation between ANKRD1 expression and E wave deceleration time. Regression line is represented within 95% confidence interval for the mean value. A negative correlation between ANKRD1 expression (−C t) and E wave deceleration time (ms) was detected (n = 21, r = −0.495, P < 0.05).

3.3. Deteriorating Cardiac Contractility Is Associated with Blunted Myocardial Vulnerability to Apoptosis

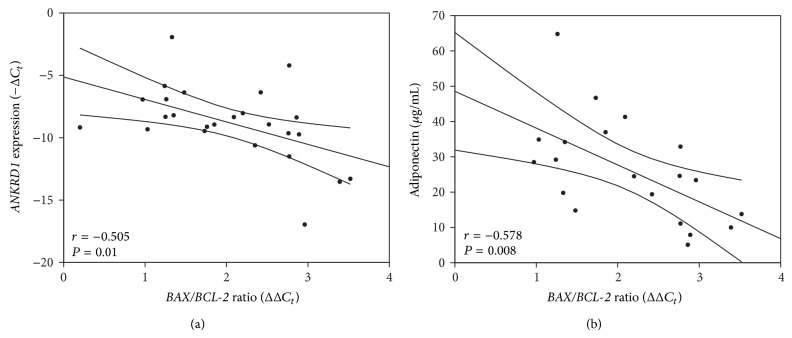

Because myocyte apoptosis is associated with contractile dysfunction in HF [18, 19] and ANKRD1 acts as antiapoptotic [10, 11], we hypothesized that decreased cardiac contractility in end-stage IDCM patients is associated with proteins involved in mechanoptosis. As presented above, the most pronounced deterioration of cardiac contractility upon IDCM progression was observed in radial direction by echocardiography, referred to as radial strain (RS). Thus, for further analysis we used RS to monitor worsening of cardiac contractility. Patients were subdivided into two groups according to the median value of RS. The above median RS group displayed normal radial cardiac contractility as mean RS was still within a healthy population reference range [20]. In contrast, patients with RS values below the median RS had severely impaired cardiac contractility (Table 4). Further strain parameters, RS rate and 3C longitudinal strain, indicated better cardiac contractility in above median RS group. None of the echocardiographic parameters or cardiac chamber pressure values reached statistically significant differences. However, the group with severe loss of radial deformation (below RS median) showed a tendency towards worse cardiac function. ANKRD1 and stretch-marker BNP levels were higher in the group with impaired radial contractility. Next, we evaluated transcript levels of proapoptotic BAX and antiapoptotic BCL-2 whose ratio defines tissue propensity to apoptosis [21] and amount of active caspase-3, a major apoptosis executer [22] that corresponds to intensity of ongoing apoptosis. Better contractility correlated with lower antiapoptotic BCL-2 levels and thus corresponded to a group more prone to apoptosis (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)). Consequently, higher levels of ongoing apoptosis, as measured by levels of active caspase-3, were detected in higher RS group (Figure 3(c)). Low BAX/BCL-2 ratios and therefore myocardial insensitivity to apoptosis correlated well with ANKRD1 transcript levels (Figure 4(a)). In addition, BAX/BCL-2 ratios inversely correlated with serum adiponectin levels (Figure 4(b)). Taken together our data imply that ANKRD1 might be involved in antiapoptotic response observed in end-stage DCM [23].

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics of patients (n = 14) with high radial strain (RS, above median) and low RS (below median).

| Radial strain | ||

|---|---|---|

| Below median | Above median | |

| Age (years) | 48 ± 6.51 | 44 ± 3.3 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 2 | 3 |

| Male | 5 | 4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.6 ± 2.0 | 27.03 ± 2.13 |

| NYHA class | ||

| III | 3 | 5 |

| III-IV | 0 | 2 |

| IV | 4 | 0 |

| BNP (pg/mL)∗ | 1824 ± 461 | 525 ± 197 |

| TnT (pg/mL) | 31.17 ± 6.1 | 157 ± 136.4 |

| Adiponectin (μg/mL)∗ | 35 ± 5.4 | 8.5 ± 1.8 |

| LVEF (%) | 21.29 ± 1.1 | 25.29 ± 3.34 |

| LVESD (mm) | 61 ± 2.1 | 55.5 ± 2.1 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 71.3 ± 2.1 | 65.6 ± 1.7 |

| RAP (mmHg) | 12.33 ± 3.9 | 9.33 ± 1.28 |

| PAP (mmHg) | 32.6 ± 4.7 | 25.3 ± 1.91 |

| PCWP (mmHg) | 23.14 ± 3.8 | 18.17 ± 1.51 |

| PVR (Wood units) | 2.5 ± 0.44 | 2.025 ± 0.55 |

| E wave (m/s) | 1 ± 0.11 | 0.92 ± 0.06 |

| A wave (m/s) | 0.398 ± 0.05 | 0.63 ± 0.095 |

| E/A | 2.71 ± 0.36 | 1.86 ± 0.48 |

| E wave T dec (ms) | 118 ± 12 | 146 ± 15.42 |

| 3C strain (%)∗ | −5.07 ± 0.96 | −8.75 ± 0.98 |

| Radial strain (%)∗ | 7.39 ± 1.23 | 21.1 ± 1.95 |

| Radial strain rate (s−1)∗ | 0.88 ± 0.19 | 1.55 ± 0.13 |

| ANKRD1 (−ΔC t)∗ | −7.02 ± 1.1 | −10.26 ± 0.68 |

| BCL-2 (−ΔC t)† | −16.36 ± 1.0 | −18.67 ± 0.22 |

| BAX (−ΔC t) | −14.60 ± 1.0 | −16.02 ± 0.17 |

| BAX/BCL-2 ratio (ΔΔC t)∗ | 1.76 ± 0.27 | 2.65 ± 0.19 |

| Active caspase-3 (ng/mg)† | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.45 ± 0.11 |

∗ P two-sided< 0.05; † P one-sided < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney U test).

Figure 3.

ANKRD1 and adiponectin upregulation are associated with antiapoptotic response in progression of IDCM. (a) Difference in BAX/BCL-2 ratio between high and low RS groups. Data are presented as mean ± 2 s.e.m; P value < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney U test). (b) Relative expression levels of BAX and BCL-2. Data are presented as mean ± 2 s.e.m. P one-sided value < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney U test). (c) Difference in active caspase-3 levels between high and low RS groups. Data are presented as mean ± 2 s.e.m; P one-sided value < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney U test); n = 6 (lower RS); n = 5 (higher RS).

Figure 4.

ANKRD1 and adiponectin correlate with tissue propensity to apoptosis. (a) Linear correlation between ANKRD1 expression and BAX/BCL-2 ratio. Regression line is represented within 95% confidence interval for the mean value. A negative correlation between ANKRD1 expression (−C t) and BAX/BCL-2 ratio (C t) was found (n = 25, r = −0.505, P = 0.01). (b) Linear correlation between adiponectin levels and BAX/BCL-2 ratio. Regression line is represented within 95% confidence interval for the mean value. A negative correlation between serum adiponectin levels (μg/mL) and cardiac BAX/BCL-2 ratio (C t) was observed (n = 20, r = −0.578, P < 0.01).

4. Discussion

Genes coding for titin binding proteins has been suggested to act as members of a titin filament based stress sensing mechanoptotic machinery in previous mouse work [3]. Here, we tested for a potential clinical significance of titin ligands for LV remodeling in IDCM patients. Out of 8 studied transcripts we found that ANKRD1 expression levels showed the most significant increase in symptomatically severe HF (NYHA class IV) compared to moderate HF (NYHA < IV) patients. Clinically, severe HF patients had notably poorer systolic strain rates indicating reduced cardiac contractility. Our data indicate that myocardial strain parameters are superior to LV ejection fraction and chamber diameter, intracardiac pressure, and relaxation measures in detecting the severity of heart failure as estimated by NYHA functional class. Our findings are in line with previous studies where myocardial strain predicted rapid HF progression in end-stage IDCM patients [1]. We found a significant reduction of longitudinal strain in 4C and 3C projections, but the major difference was observed for radial strain measurements. These findings are in line with a study on hypertensive patients with heart failure, where a reduction in radial strain was only seen in NYHA classes III-IV, whereas longitudinal strain was decreased as early as NYHA class II [24]. Moreover we found that ANKRD1 expression correlated not only with reduced LV contractility, but also with increased cardiac stiffness; ANKRD1 expression positively correlated with shortening of E wave deceleration time, marking restrictive filling pattern—the most powerful independent prognostic indicator of poor outcome or transplantation in DCM patients [25]. Taken together our data indicate that ventricular ANKRD1 levels in IDCM patients are associated with progression of LV remodeling, resulting in reduced cardiac contractility and compliance. In DCM, myocyte apoptosis is related to LV dysfunction [26] and appears to directly affect cardiac contractility [18, 19]. Finally, myocardial ANKRD1 functions as an antiapoptotic survival factor after ischemia-reperfusion injury [10] and hypoxia [11]. Therefore, we investigated the relation between ANKRD1 expression and apoptotic status in the myocardium. We found that tissue samples more susceptible to apoptosis (high BAX/BCL-2 ratio) had lower ANKRD1 levels than apoptosis-resistant samples (low BAX/BCL-2 ratio) implying that ANKRD1 could act as myocyte survival factor. However, counterintuitively the group with less impaired cardiac contractility (above median RS) was more prone to apoptosis than low RS group. In addition, impaired contractility was associated with higher BAX/BCL-2 ratios and elevated levels of key apoptosis-executing enzyme [22] and active caspase-3, indicating that better contractility was marked with higher levels of ongoing apoptosis. These findings correspond to previous observations that terminal IDCM stage is associated with marked antiapoptotic response [23]. In agreement with previous data on end-stage HF [27], we found that a decreased BAX/BCL-2 ratio in hearts with severely impaired contractility was mainly due to increased levels of the survival factor Bcl-2. Moreover, insensitivity to apoptosis was associated with increased serum adiponectin levels, a predictor for mortality in patients with chronic HF [28]. Possibly, adiponectin could account for the reduced BAX/BCL-2 ratio in end-stage IDCM patients, as it has antiapoptotic effects in myocardium [29].

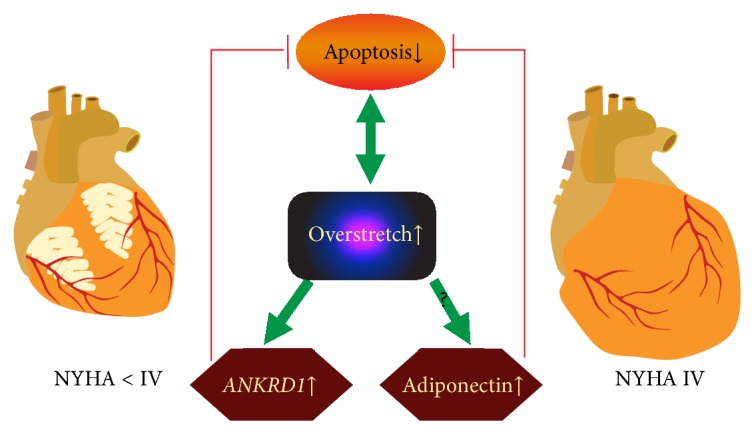

Speculatively, stretch-sensing and prosurvival properties of Ankrd1 could be responsible for the observed antiapoptotic response in terminal IDCM stages (Figure 5). LV remodeling in IDCM leading to the wall thickening and chamber dilation is accompanied by myocyte overstretch and slippage [30] which in vicious cycle provokes myocyte mechanoptosis [31]. Subsequently stretch would directly upregulate ANKRD1 transcript and launch Ankrd1-mediated survival cascades. Hypothetically, ANKRD1 and adiponectin or their agonists could be used as heart-specific antiapoptotic agents in treatment of IDCM.

Figure 5.

Antiapoptotic response in end-stage IDCM. Speculatively, ongoing apoptosis and myocyte overstretch in vicious cycle mediate the LV remodeling, whereas myocyte stretch induces Ankrd1 expression and increases adiponectin levels by unknown mechanism that in turn inhibit apoptotic signaling. Arrows indicate process dynamics in NYHA <IV to NYHA IV transition.

This study has some limitations which have to be pointed out. The study cohort consisted of patients with advanced HF (NYHA classes III-IV); thus future research would be needed to confirm the validity of observed clinical correlations in patients with mild HF (NYHA I-II). Recent studies have demonstrated that genetic alterations of titin [32] and ANKRD1 [33, 34] are associated with DCM and result in poorer prognosis [32]. Thus, it is not excluded that genetic alterations of titin-ligand network might be present in studied patients. However, observed upregulation of ANKRD1 is very likely to be universal pathophysiological as it was described in controlled increased stretch states such as experimental pressure overload [5] and not due to genetic alterations. This study was based on patients with advanced stages of HF (mostly NYHA classes III-IV); thus future research would be needed to evaluate the validity of observed clinical correlations in early HF (NYHA I-II).

Although transcript levels do not always represent changes in protein concentration, our data suggest that ANKRD1 transcript quantification is sensitive test for monitoring progression of advanced IDCM stages. Moreover, quantitative RT-PCR might be method of choice to quantify ANKRD1 levels, when using minute EMB samples.

In conclusion, expression profiling of selected mechanoptotic machinery members revealed association between increased ANKRD1 expression and deterioration of cardiac contractility and compliance in IDCM patients. Therefore, elevated ANKRD1 expression could serve as potential clinical marker to uncover a coming need to plan heart transplantation in end-stage HF patients. Further research is warranted on the functional roles of ANKRD1 induction in IDCM associated apoptosis.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1 Pharmacological heart failure therpay of studied cohort. Supplementary Table 2 List of Taqman probes used in this study.

Acknowledgments

Virginija Grabauskienė and Dainius Daunoravičus are funded by a grant (no. MIP-086/2012); Julius Bogomolovas, Virginija Grabauskienė, Daiva Bironaitė, and Virginija Bukelskienė are funded by a grant (MIP-011/2014) from the Research Council of Lithuania. Siegfried Labeit is supported by DFG (La668/11-2 and La668/15-1) and EU-FP7 (SarcoSi). Christian C. Witt is grateful for the generous support of DFG (La668/15-1 and Wi3278/2-2).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Jasaityte R., Dandel M., Lehmkuhl H., Hetzer R. rediction of short-term outcomes in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy referred for transplantation using standard echocardiography and strain imaging. Transplantation Proceedings. 2009;41(1):277–280. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang P. M., Izumo S. Apoptosis and heart failure: a critical review of the literature. Circulation Research. 2000;86(11):1107–1113. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.86.11.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knöll R., Buyandelger B. Z-disc transcriptional coupling, sarcomeroptosis and mechanoptosis. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2013;66(1):65–71. doi: 10.1007/s12013-012-9430-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller M. K., Bang M.-L., Witt C. C., et al. The muscle ankyrin repeat proteins: CARP, ankrd2/Arpp and DARP as a family of titin filament-based stress response molecules. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2003;333(5):951–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aihara Y., Kurabayashi M., Saito Y., et al. Cardiac ankyrin repeat protein is a novel marker of cardiac hypertrophy: role of M-CAT element within the promoter. Hypertension. 2000;36(1):48–53. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.36.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagueh S. F., Shah G., Wu Y., et al. Altered titin expression, myocardial stiffness, and left ventricular function in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2004;110(2):155–162. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000135591.37759.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei Y.-J., Cui C.-J., Huang Y.-X., Zhang X.-L., Zhang H., Hu S.-S. Upregulated expression of cardiac ankyrin repeat protein in human failing hearts due to arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2009;11(6):559–566. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moulik M., Vatta M., Witt S. H., et al. ANKRD1, the gene encoding cardiac ankyrin repeat protein, is a novel dilated cardiomyopathy gene. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;54(4):325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arimura T., Bos J. M., Sato A., et al. Cardiac ankyrin repeat protein gene (ANKRD1) mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;54(4):334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee M.-J., Kwak Y.-K., You K.-R., Lee B.-H., Kim D.-G. Involvement of GADD153 and cardiac ankyrin repeat protein in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Experimental and Molecular Medicine. 2009;41(4):243–252. doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.4.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han X.-J., Chae J.-K., Lee M.-J., You K.-R., Lee B.-H., Kim D.-G. Involvement of GADD153 and cardiac ankyrin repeat protein in hypoxia-induced apoptosis of H9c2 cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(24):23122–23129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501095200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee P. J., Rudenko D., Kuliszewski M. A., et al. Survivin gene therapy attenuates left ventricular systolic dysfunction in doxorubicin cardiomyopathy by reducing apoptosis and fibrosis. Cardiovascular Research. 2014;101(3):423–433. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura T., Ueda Y., Juan Y., Katsuda S., Takahashi H., Koh E. Fas-mediated apoptosis in Adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy in rats: in vivo study. Circulation. 2000;102(5):572–578. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen B., Zhong L., Roush S. F., et al. Disruption of a GATA4/Ankrd1 signaling axis in cardiomyocytes leads to sarcomere disarray: implications for anthracycline cardiomyopathy. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035743.e35743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan J. S., Reed A., Chen F., Stewart C. N., Jr. Statistical analysis of real-time PCR data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7, article 85 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberg N. L., Firstenberg M. S., Castro P. L., et al. Doppler-derived myocardial systolic strain rate is a strong index of left ventricular contractility. Circulation. 2002;105(1):99–105. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Little W. C., Ohno M., Kitzman D. W., Thomas J. D., Cheng C.-P. Determination of left ventricular chamber stiffness from the time for deceleration of early left ventricular filling. Circulation. 1995;92(7):1933–1939. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.92.7.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wencker D., Chandra M., Nguyen K., et al. A mechanistic role for cardiac myocyte apoptosis in heart failure. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;111(10):1497–1504. doi: 10.1172/JCI200317664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laugwitz K.-L., Schömig A., Ungerer M., et al. Blocking caspase-activated apoptosis improves contractility in failing myocardium. Human Gene Therapy. 2001;12(17):2051–2063. doi: 10.1089/10430340152677403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng S., Larson M. G., McCabe E. L., et al. Age- and sex-based reference limits and clinical correlates of myocardial strain and synchrony: the framingham heart study. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2013;6(5):692–699. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oltvai Z. N., Milliman C. L., Korsmeyer S. J. Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programed cell death. Cell. 1993;74(4):609–619. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90509-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen G. M. Caspases: the executioners of apoptosis. The Biochemical Journal. 1997;326(1):1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3260001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akyürek Ö., Akyürek N., Sayin T., et al. Association between the severity of heart failure and the susceptibility of myocytes to apoptosis in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. International Journal of Cardiology. 2001;80(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5273(01)00451-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosmala W., Plaksej R., Strotmann J. M., et al. Progression of left ventricular functional abnormalities in hypertensive patients with heart failure: an ultrasonic two-dimensional speckle tracking study. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2008;21(12):1309–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rihal C. S., Nishimura R. A., Hatle L. K., Bailey K. R., Tajik A. J. Systolic and diastolic dysfunction in patients with clinical diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy: relation to symptoms and prognosis. Circulation. 1994;90(6):2772–2779. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.90.6.2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ibe W., Saraste A., Lindemann S., et al. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis is related to left ventricular dysfunction and remodelling in dilated cardiomyopathy, but is not affected by growth hormone treatment. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2007;9(2):160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Latif N., Khan M. A., Birks E., et al. Upregulation of the Bcl-2 family of proteins in end stage heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2000;35(7):1769–1777. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00647-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kistorp C., Faber J., Galatius S., et al. Plasma adiponectin, body mass index, and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;112(12):1756–1762. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.530972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y., Wang X.-L., Zhao J., et al. Adiponectin inhibits oxidative/nitrative stress during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion via PKA signaling. American Journal of Physiology—Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;305(12):E1436–E1443. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00445.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beltrami C. A., Finato N., Rocco M., et al. Structural basis of end-stage failure in ischemic cardiomyopathy in humans. Circulation. 1994;89(1):151–163. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.89.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng W., Li B., Kajstura J., et al. Stretch-induced programmed myocyte cell death. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;96(5):2247–2259. doi: 10.1172/JCI118280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herman D. S., Lam L., Taylor M. R. G., et al. Truncations of titin causing dilated cardiomyopathy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(7):619–628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moulik M., Vatta M., Witt S. H., et al. ANKRD1, the gene encoding cardiac ankyrin repeat protein, is a novel dilated cardiomyopathy gene. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;54(4):325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duboscq-Bidot L., Charron P., Ruppert V., et al. Mutations in the ANKRD1 gene encoding CARP are responsible for human dilated cardiomyopathy. European Heart Journal. 2009;30(17):2128–2136. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1 Pharmacological heart failure therpay of studied cohort. Supplementary Table 2 List of Taqman probes used in this study.