Abstract

More than 10% of the population in Europe and North America suffer from IgE-associated allergy to grass pollen. In this article, we describe the development of a vaccine for grass pollen allergen-specific immunotherapy based on two recombinant hypoallergenic mosaic molecules, designated P and Q, which were constructed out of elements derived from the four major timothy grass pollen allergens: Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, and Phl p 6. Seventeen recombinant mosaic molecules were expressed and purified in Escherichia coli using synthetic genes, characterized regarding biochemical properties, structural fold, and IgE reactivity. We found that depending on the arrangement of allergen fragments, mosaic molecules with strongly varying IgE reactivity were obtained. Based on an extensive screening with sera and basophils from allergic patients, two hypoallergenic mosaic molecules, P and Q, incorporating the primary sequence elements of the four grass pollen allergens were identified. As shown by lymphoproliferation experiments, they contained allergen-specific T cell epitopes required for tolerance induction, and upon immunization of animals induced higher allergen-specific IgG Abs than the wild-type allergens and a registered monophosphoryl lipid A–adjuvanted vaccine based on natural grass pollen allergen extract. Moreover, IgG Abs induced by immunization with P and Q inhibited the binding of patients’ IgE to natural allergens from five grasses better than IgG induced with the wild-type allergens or an extract-based vaccine. Our results suggest that vaccines based on the hypoallergenic grass pollen mosaics can be used for immunotherapy of grass pollen allergy.

Introduction

Immunoglobulin E–mediated allergies to grass pollen represent a worldwide health problem with increasing prevalence affecting >10% of the population in Europe and North America (1, 2). In grass pollen–sensitized patients, the heavy pollen load during spring and early summer leads to severe respiratory symptoms such as rhinitis and asthma (3). Allergen-specific immunotherapy (SIT) is considered the only allergen-specific and disease-modifying therapy of allergy (4) with long-lasting clinical effects (5). Furthermore, SIT has been demonstrated to prevent the onset of allergic asthma in grass pollen–allergic children (6). The first SIT trial was already reported in 1911, when Leonard Noon injected grass pollen extract into hay fever patients and observed improvement of symptoms by conjunctival provocation testing of patients (7). However, a major disadvantage of SIT is the risk for inducing side effects in the treated patients, which may be life-threatening when anaphylactic reactions develop. Severe negative side effects have been reported in particular for grass pollen immunotherapy (8). Another problem related to allergen extract–based SIT is that important allergens are not present in sufficient quantities in the allergen extract or induce low or no protective immune responses (9, 10).

Strategies were developed to reduce negative side effects to avoid the risk for anaphylactic reactions upon administration of allergens. One possible approach for reducing the allergenic activity of allergens themselves was proposed in 1970 by David Marsh, who suggested the preparation of allergoids by formaldehyde treatment of allergen extracts (11). However, one major problem of this approach is that the resulting allergoids may show large variations regarding immunogenicity and reduced allergenic activity.

During the last 25 years many of the clinically relevant allergens have been characterized by isolating their cDNAs and by the production of recombinant allergens (12, 13). Moreover, it was possible to manipulate allergen sequences and to produce allergen derivatives with reduced IgE reactivity and allergenic activity with the aim to avoid IgE-mediated side effects (14–16). The major grass pollen allergens that are essential for the formulation of a grass pollen allergy vaccine have been characterized (17–19), and a vaccine based on four recombinant timothy grass pollen allergens, Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, and Phl p 6, has been shown to be clinically effective for the treatment of grass pollen allergy (20).

The goal of this study was the development of a hypoallergenic vaccine for the treatment of grass pollen allergy that combines hypoallergenic fragments from different grass pollen allergens in the form of hybrid proteins. We have previously produced hypoallergenic mosaic proteins for Phl p 1 (21) and one combining Phl p 2 and Phl p 6 (22). We also found that a mosaic consisting of four rearranged portions of Phl p 5 showed reduced IgE reactivity (M. Focke and R. Valenta, unpublished observations).

In an extensive molecular evolution process the four major grass pollen allergens were converted into two hypoallergenic derivatives containing the relevant epitopes required for the induction of allergen-specific blocking IgG Abs and T cell tolerance. For this purpose, >20 recombinant fragments of the four grass pollen allergens were recombined as mosaic proteins, tested for IgE reactivity, allergenic activity, presence of T cell epitopes, and ability to induce allergen-specific IgG Abs that inhibit allergic patients’ IgE binding to allergens. In particular, we compared the two fusion proteins with a natural allergen extract–based grass pollen vaccine regarding their ability to induce blocking IgG Abs by immunization experiments. Furthermore, the protective effect of antisera raised against the mosaic proteins was investigated in vivo in a murine model of grass pollen allergy.

Materials and Methods

Grass pollen–allergic patients, recombinant allergens, and grass pollen extracts

Allergic patients were characterized by a history of seasonal grass pollen allergy and the presence of grass pollen–specific serum IgE levels, as determined by ImmunoCAP (Thermo Fisher, Uppsala, Sweden) or the CLA Allergy Test (Hitachi Chemical Diagnostics, Mountain View, CA). The allergen profile recognized by IgE in sera of blood donors used for all cellular assays was determined by ImmunoCAP ISAC (Thermo Fisher, Uppsala, Sweden). The demographic, clinical, and serologic characterization of 72 patients is provided in Supplemental Table I. Three nonallergic individuals and two allergic patients without grass pollen allergy (Supplemental Table I) were included for control purposes. All experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna, and informed consent was obtained from the subjects. Recombinant purified timothy grass pollen allergens (rPhl p 1, rPhl p 2, rPhl p 5, and rPhl p 6) were obtained from Biomay AG (Vienna, Austria). Natural timothy grass pollen extract was prepared as previously described (9). The grass pollen extract mix from five grasses (Phleum pratense, Dactylis glomerata, Anthoxanthum odoratum, Lolium perenne, Poa pratensis) was purchased from Stallergenes (Antony, France).

Construction, expression, and purification of the mosaic molecules

The amino acid sequences of all mosaic molecules are based on combinations of the allergen-derived fragments shown in Fig. 1 and Supplemental Table II without insertion of any linker sequences. The mosaics were named by letters in alphabetical order (A–Q) and are summarized in Fig. 2A. The DNA sequences encoding the mosaic molecules were codon-optimized for the expression in Escherichia coli and synthesized by ATG Biosynthetics (Merzhausen, Germany). An NdeI restriction site including the start codon was added at the 5′ end, and a 6× Histidine tag followed by a stop codon and an EcoRI restriction site was added at the 3′ end of each sequence. The resulting genes were cloned into the expression plasmid pET17b (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and the correct sequences were verified by DNA sequencing (ATG Biosynthetics).

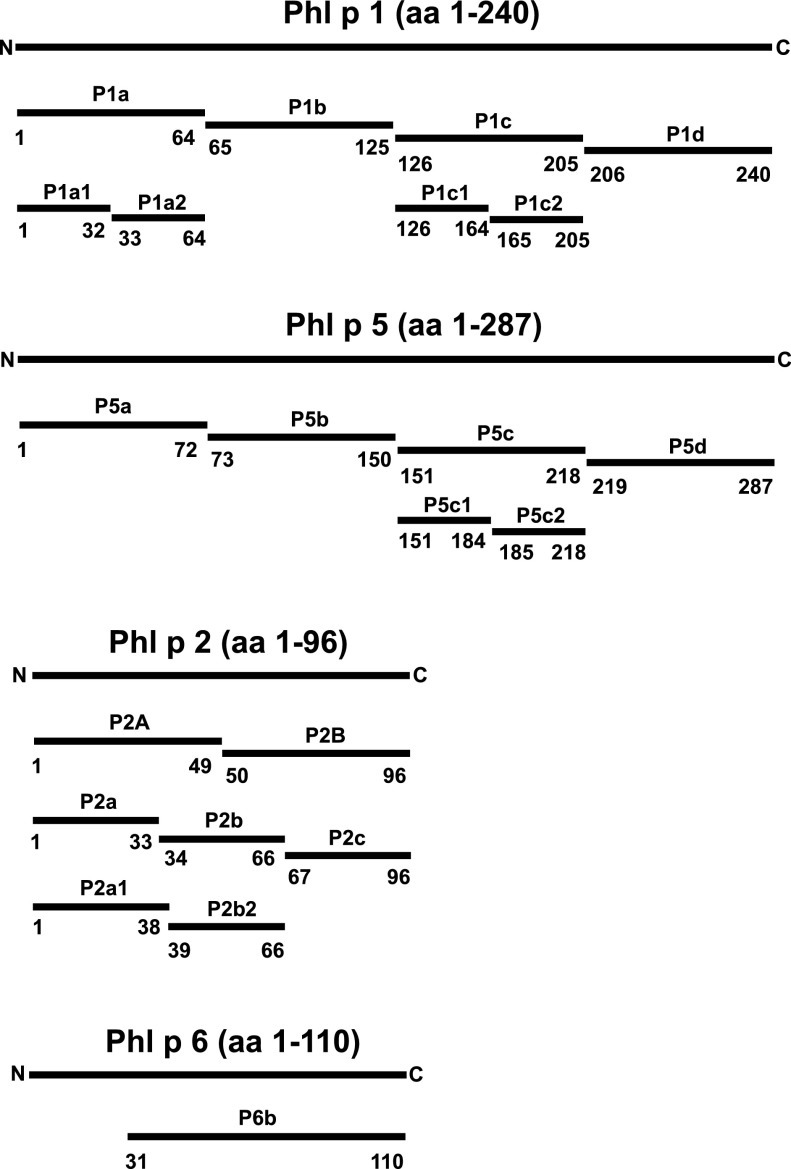

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of Phl p 1–, Phl p 5–, Phl p 2–, and Phl p 6–derived fragments. The position of each fragment within the allergen sequence is indicated.

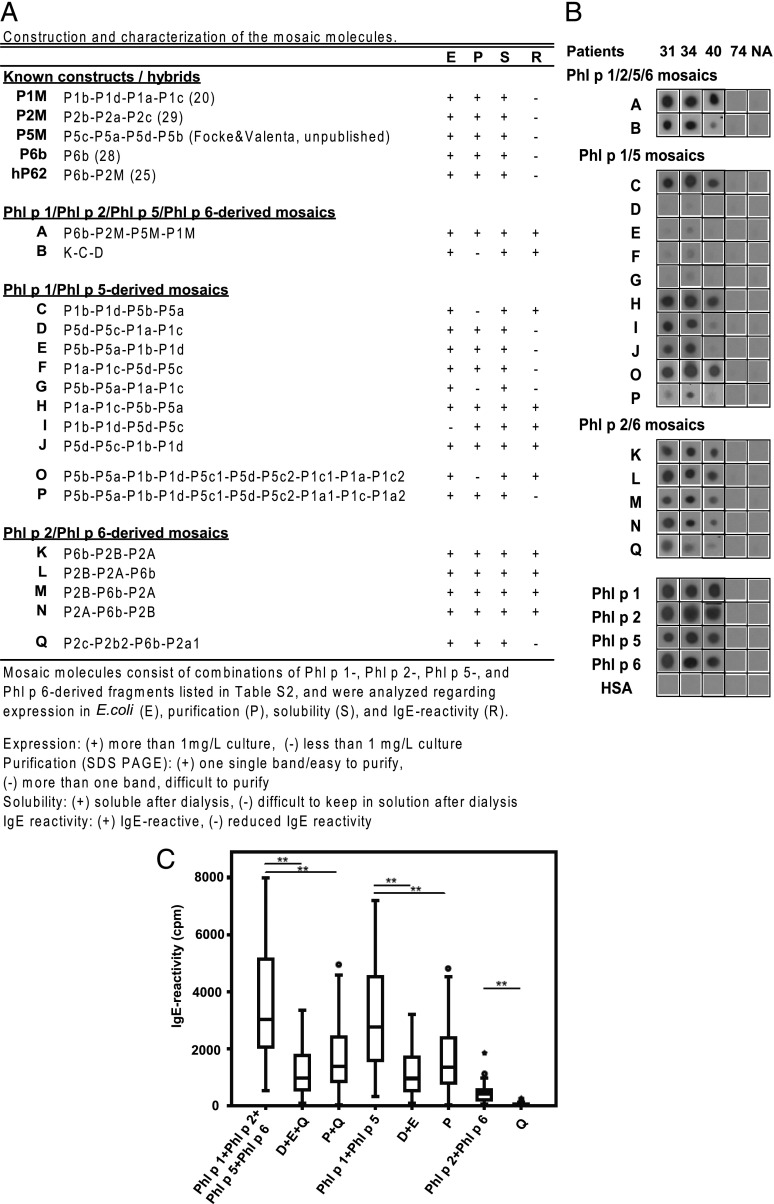

FIGURE 2.

Construction and characterization of the mosaic molecules. (A) Representative IgE reactivity of hybrids A–Q. Purified recombinant hybrid proteins, wild-type allergens, and HSA were dotted onto nitrocellulose and tested for IgE reactivity with sera from grass pollen–allergic patients. (B) Results from three representative patients (31, 34, 40), from a nonallergic (NA) patient, and from an allergic subject without grass pollen allergy (patient 74) are shown. Reduced grass pollen–allergic patients’ IgE reactivity to the mosaics D, E, P, and Q. Sera from 57 grass pollen–allergic patients were tested for IgE reactivity to nitrocellulose-dotted mosaics D, E, P, and Q, and to the wild-type allergens Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, and Phl p 6, as indicated on the x-axis. (C) IgE reactivity was quantified by gamma counting (cpm values: y-axis) of bound [125I]-labeled anti-IgE Abs. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

All constructs were expressed and purified according to a standard protocol, which was adapted to the individual proteins by minor changes, mainly in incubation time and pH. In brief, all constructs were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) in liquid culture. Cells were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.5 in Luria Bertani broth medium containing 100 mg/l ampicillin. The protein expression was induced by adding isopropyl-β-thiogalactopyranoside to a final concentration of 0.5 mM and further culturing of the cells for 4 h at 37°C. E. coli cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris, and 8 M urea (pH 8.0). After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 30 min, the supernatant was loaded on a nickel column (Qiagen), unbound material was washed out with 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris, and 8 M urea (pH 6.3). The proteins were eluted using 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris, and 8 M urea (pH 4.9). The purified proteins were refolded by stepwise dialysis against a gradient from 6 to 0 M urea. Finally, the proteins were dialyzed against PBS. Protein purity was confirmed by SDS-PAGE, and the concentration of the purified samples was estimated by UV absorption at 280 nm or using the Micro BCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Solubility of the purified proteins was tested by centrifugation experiments.

Grass pollen–allergic patients’ IgE reactivity to the hybrids A–Q

Direct binding of serum IgE from grass pollen–allergic patients (1–57; Supplemental Table I) to the Phl p 1–, Phl p 2–, Phl p 5–, and Phl p 6–derived mosaic molecules A–Q, or rPhl p 1, rPhl p 2, rPhl p 5, and rPhl p 6 was investigated by nondenaturing, RadioAllergoSorbent test–based dot-blot experiments (21). For control purposes, sera of individuals not allergic to grass pollen were included (patients 73 and 74). Two-microliter aliquots of the purified hybrid proteins (concentration 0.5 μg/μl), equimolar amounts of each of the recombinant wild-type allergens, and human serum albumin (HSA; negative control) were dotted onto nitrocellulose strips. The strips were dried and exposed to patients’ sera (diluted 1:10), and bound IgE Abs were detected with a [125I]-labeled anti-human IgE Ab (diluted 1:20; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) and visualized by autoradiography (23). The gamma radiation emitted by the individual dots corresponding to bound IgE was subsequently quantified (cpm) by measurement in a gamma counter (Wallac, HVD, Turku, Finland).

Circular dichroism measurements

Far UV CD spectra of proteins were collected on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter (Japan Spectroscopic, Tokyo, Japan) at room temperature, using a 0.1-cm path-length quartz cuvette. Three independent measurements were recorded and averaged for each spectral point. The final spectra were baseline corrected by subtracting the corresponding buffer spectra obtained under identical conditions. Results were expressed as the mean residue ellipticity [θ] at a given wavelength (24).

Proliferation and cytokine responses of PBMCs from grass pollen–allergic patients

Heparinized venous blood samples were collected from eight grass pollen–allergic patients (patients 58–62, 68, 71, and 72; Supplemental Table I), two allergic patients not sensitized to grass pollen (patients 73 and 74; Supplemental Table I), and three nonallergic individuals. PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation and stimulated with the recombinant allergens (mixtures of Phl p 1 + Phl p 5, Phl p 2 + Phl p 6, or mosaic molecules D+E, P, or Q; total protein concentrations: 2.5, 1.25 μg/ml) or for control purposes, with IL-2 (4 U/well; Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) as positive control, HSA, or medium alone (negative controls) in triplicates. After 6 d, cell proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation (0.5 μCi/well) and expressed as cpm values after reduction of medium values. Cytokine levels (IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, and IFN-γ) were quantified in supernatants from PBMC cultures, which were prepared as for the proliferation experiments. Luminex fluorescent bead–based technology and a Luminex 100 system were used for measurements (Luminex, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Results are shown for the 2.5 μg/ml protein concentration.

Immunization of mice and rabbits

Female 6- to 8-wk-old BALB/c mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Sulzfeld, Germany) and housed at the animal facility of the Department of Pathophysiology and Allergy Research according to the local guidelines. All animal experiments were approved by the local review board. Groups of mice (n = 5) were immunized s.c. twice in 4-wk intervals with rPhl p 1 + rPhl p 5 (5 μg of each), D+E (5 μg of each), P (10 μg), rPhl p 2 + rPhl p 6 (5 μg of each), or Q (10 μg). The proteins were adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide (Alu-Gel-S; Serva, Ingelheim, Germany). Sera were obtained via bleeding from the tail vein of mice and stored at −20°C until use. Measurements of IgE and IgG1 Abs specific for rPhl p 1, rPhl p 2, rPhl p 5, and rPhl p 6 were done as described previously (21).

For the generation of larger volumes of sera containing polyclonal IgG Abs against the hybrid proteins D, E, P, and Q, rabbits were immunized with D, E, P, or Q (200 μg per injection) using Freund’s complete (1st immunization) and incomplete adjuvant (booster immunization; Charles River Laboratories). For comparison, rabbit sera were generated in the same manner by immunization with each of the recombinant allergens, rPhl p 1, rPhl p 2, rPhl p 5, or rPhl p 6, or by four immunizations with the registered grass pollen allergy vaccine Pollinex Quattro Plus 1.0 ml (Bencard, Munich, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation.

ELISA inhibition experiments

The ability of rabbit IgG Abs induced by immunization with the mosaic proteins D, E, P, and Q for inhibiting the binding of allergic patients’ IgE to rPhl p 1, rPhl p 2, rPhl p 5, and rPhl p 6 was examined by an ELISA competition assay as described (25). In brief, ELISA plates (Nunc Maxisorp, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with either natural timothy grass pollen extract or a commercial five-grass pollen allergen extract (20 μg/ml; Stallergenes) and preincubated with 1/50 dilutions of the rabbit anti-D, -E, -P, and -Q antisera, the rabbit anti-Phl p 1, -Phl p 2, -Phl p 5, and -Phl p 6 antisera, or anti-Pollinex antiserum. After washing, plates were incubated with 1/10 diluted sera from grass pollen–allergic patients or a nonatopic blood donor. Bound IgE Abs were detected with HRP-coupled goat anti-human IgE Abs (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD), diluted 1/2500. The percentage of inhibition of IgE-binding achieved by preincubation with the rabbit anti-sera was calculated as follows: percentage of inhibition of IgE binding = 100 − ODI/ODP × 100. ODI and ODP represent the extinctions after preincubation with the rabbits’ immune sera and the corresponding preimmune sera, respectively.

Basophil activation experiments

Heparinized peripheral blood samples were obtained from grass pollen–allergic patients after informed consent was obtained. Blood samples (100 μl) were incubated with serial dilutions of recombinant allergens or allergen derivatives, or an anti-IgE Ab (1 μg/ml) as positive control, or PBS for 15 min (37°C). Mixtures of recombinant allergens and mosaic proteins were added in equimolar concentrations. The protein concentrations shown in Fig. 6 represent total protein amounts added to each well. Cells were washed in PBS containing 20 mM EDTA and incubated with 10 μl PE-conjugated CD203c mAb 97A6 (Immunotech, Marseille, France) for 15 min at room temperature. Thereafter, samples were subjected to erythrocyte lysis with 2 ml FACS Lysing Solution (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Then cells were washed, resuspended in PBS, and analyzed by two-color flow cytometry on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson). Allergen-induced upregulation of CD203c was calculated from mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) obtained with stimulated (MFIstim) and unstimulated (MFIcontrol) cells, and expressed as stimulation index (MFIstim:MFIcontrol) (26).

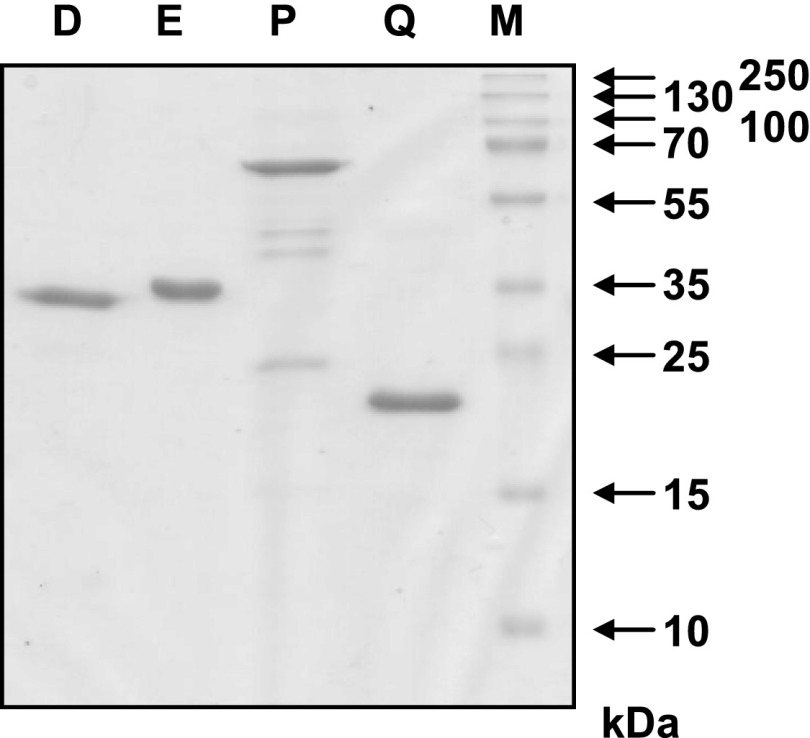

FIGURE 6.

Proliferation of PBMCs from eight grass pollen–allergic patients (open circles) and five controls (open squares) either not sensitized to grass pollen or nonatopic, in response to 2.5 μg/ml (A) and 1.25 μg/ml (B) of grass pollen allergens and mosaic molecules. Proliferation in response to the mosaic molecules D+E, P, and Q and grass pollen allergens Phl p 1+Phl p 5 (P1+P5) and Phl p 2+Phl p 6 (P2+P6) (x-axis) is represented as cpm values over medium control (y-axis). *p < 0.05.

Development of a murine model for the treatment of grass pollen allergy

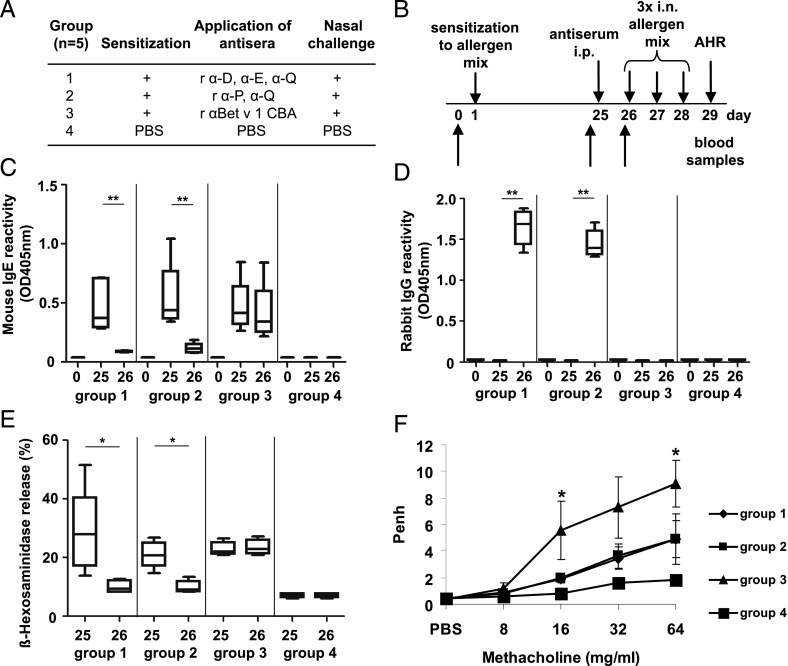

Three groups of BALB/c mice (n = 5) were sensitized to a mix of Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, and Phl p 6 adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide by one s.c. injection (5 μg of each allergen), or PBS in alum was injected (group 4). On day 25, rabbit anti-D, anti-E, and anti-Q antisera (group 1), or rabbit anti-P and anti-Q antisera (group 2), or an irrelevant rabbit antiserum (anti-Bet v 1 derivative, group 3) (27), or PBS (group 4) were applied i.p. (200 μl of each antiserum). Blood samples were taken on days 0, 25, and 26. Mouse IgE and rabbit IgG in mouse sera specific for Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, and Phl p 6 were detected by ELISA as described previously (21). ELISA plates were coated with a mix of Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, and Phl p 6 (5 μg of each allergen/ml bicarbonate buffer); sera were diluted 1:10 for IgE detection and 1:50,000 for rabbit IgG detection. The degranulation experiment of rat basophil leukemia cells was performed as previously described (28). Cells were cultivated overnight in 96-well plates, washed twice, and incubated with mouse serum diluted 1:10 in Tyrode’s buffer, together with a mix of Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, and Phl p 6 (0.1 μg/ml of each allergen) for 2 h, and β-hexosaminidase release was measured in supernatants. On 3 consecutive days (days 26–28), a mix of Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, and Phl p 6 (5 μg of each allergen in a total volume of 50 μl) per mouse (groups 1–3) or PBS (group 4) was given intranasally to anesthetized mice (29). Airway hyperreactivity was assessed on day 29 by measurement of Penh (enhanced pause) by whole-body plethysmography (Buxco, Winchester, U.K.) as described previously (30). Mice were positioned in calibrated aerosol exposure chambers, exposed to increasing concentrations of methacholine (8, 16, 32, 64 mg/ml), and Penh was recorded.

Statistical analysis

Data were tested for normality of distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. For comparison of groups, the Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired data was performed using SPSS software. Results are either shown as Tukey box plots (50% of the values are within the boxes, median values are shown for each group; whiskers represent minimum and maximum values within the 1.5 interquartile range; outliers are shown as circles or as scatter plots with median values). Graphs were made using GraphPad Prism software. Significant differences between groups are indicated (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Results

Breeding of a hypoallergenic grass pollen allergy vaccine consisting of mosaic molecules

The rationale behind the construction of a hypoallergenic grass pollen allergy vaccine was to recombine fragments of the major grass pollen allergens Phl p 1 and Phl p 5 and the important grass pollen allergens Phl p 2 and Phl p 6. The fragments were selected: 1) to reduce their IgE reactivity and allergenic activity, 2) to incorporate sequences that upon immunization induce IgG Abs that block allergic patients’ IgE toward the IgE epitopes of the wild-type allergens, and 3) to incorporate the majority of the known T cell epitopes in an intact form (Supplemental Tables II and III). In an initial step, we thought to combine hypoallergenic mosaic molecules made for the individual grass pollen allergens (i.e., P1M: Phl p 1; P2M: Phl p 2; P5M: Phl p 5; P6b: Phl p 6) within one molecule by fusing the corresponding genes in the order P6b-P2M-P5M-P1M (Figs. 1 and 2A) and obtained the fusion protein A, which was expressed in E. coli. However, as exemplified in Fig. 2B, fusion protein A still showed considerable IgE reactivity. This finding was unexpected because each of the mosaic proteins used for construction (i.e., P1M, P2M, P5M, P6b) had shown low or no IgE reactivity when tested as an individual protein (Fig. 2B).

Because combination of the existing hypoallergenic derivatives of the four grass pollen allergens did not lead to a sufficiently hypoallergenic fusion protein, we designed new mosaic proteins as building blocks for fusion proteins. Eight mosaic proteins (Fig. 2A, C–J), consisting of different combinations of two fragments of Phl p 1 and two fragments of Phl p 5, were prepared to reassemble the fragments of P1M and P5M. In addition, four mosaic proteins (Fig. 2A, K–N) combining fragments derived from Phl p 2 and Phl p 6 were generated. In an attempt to obtain a hypoallergenic mosaic consisting of fragments of all four allergens (i.e., Phl p 1, 2, 5, and 6), we engineered the derivative B, which was made out of K, C, and D of the former variants (Fig. 2A), but again found that this fusion protein did not show a satisfying reduction of IgE reactivity because K and C showed IgE reactivity (Figs. 1, 2A, 2B, and Supplemental Table II).

Also, the testing for IgE reactivity of the individual mosaic proteins intended to be used as building blocks revealed an unexpected behavior. Hybrids E and G showed strongly reduced IgE reactivity, whereas C and H containing the same pieces in different order showed IgE reactivity (Fig. 2A, 2B). Interestingly, positioning the Phl p 5–derived fragments P5b-P5a at the C terminus gave an IgE-reactive protein, whereas a strong reduction of IgE binding was obtained when the fragments were added to the N terminus (Fig. 2A, 2B). Because mosaics D and E exhibited a strongly reduced IgE reactivity and together covered the whole sequence of Phl p 1 and Phl p 5, these two molecules were considered as possible candidate molecules for the grass pollen vaccine and subjected to further evaluation.

When we used a similar approach for engineering fusion proteins consisting of Phl p 2 and Phl p 6 fragments with the mosaic approach (Figs. 1 and 2A, K–N), we were not able to obtain derivatives with sufficiently reduced IgE reactivity (Fig. 2A, 2B). Because fragmentation of Phl p 2 in only two portions yielded an insufficient reduction of IgE binding, we prepared three fragments. According to the crystal structure of Phl p 2 with an IgE-blocking Ab (31), the binding site was divided into three pieces, which were rearranged and interrupted by insertion of the Phl p 6 fragment P6b (Fig. 2A, Supplemental Table II) to yield the mosaic Q, which indeed showed reduced IgE reactivity (Fig. 2A, 2B).

Further assembly of allergen-derived fragments decreases the number of molecules included in the vaccine

Next, we thought to obtain derivatives that incorporate the primary sequence of both Phl p 1 and Phl p 5 within one molecule. First, we tested mosaics D–G with a large number of sera from grass pollen–allergic patients (n > 60). Fragments D and E, but unexpectedly not F and G containing similar building blocks, showed a consistent reduction of IgE reactivity (data not shown). The remaining IgE reactivity of F and G appeared to be due to fragments P1a, P1c, and P5c (data not shown). We therefore redesigned mosaics (Fig. 2A, Supplemental Table II: O, P) in which the Phl p 1 fragments P1a and P1c and the Phl p 5 fragment P5c were further divided into two fragments each for the construction of fusion proteins comprising the complete sequence of Phl p 1 and Phl p 5. As exemplified in Fig. 2B, mosaic P showed a reduced IgE reactivity. Interestingly, mosaic O, which contains the same building blocks as mosaic P, showed much stronger IgE reactivity than P, again indicating that the order of building blocks has an influence on the re-formation of IgE epitopes within mosaic proteins. A large mosaic B consisting of K-C-D also remained IgE-reactive, which was not surprising given that K and C showed IgE reactivity. We therefore finally subjected the fragments D and E and mosaic P, comprising Phl p 1 and Phl p 5, as well as Q, comprising Phl p 2 and Phl p 6, to further evaluation regarding IgE reactivity and structural behavior.

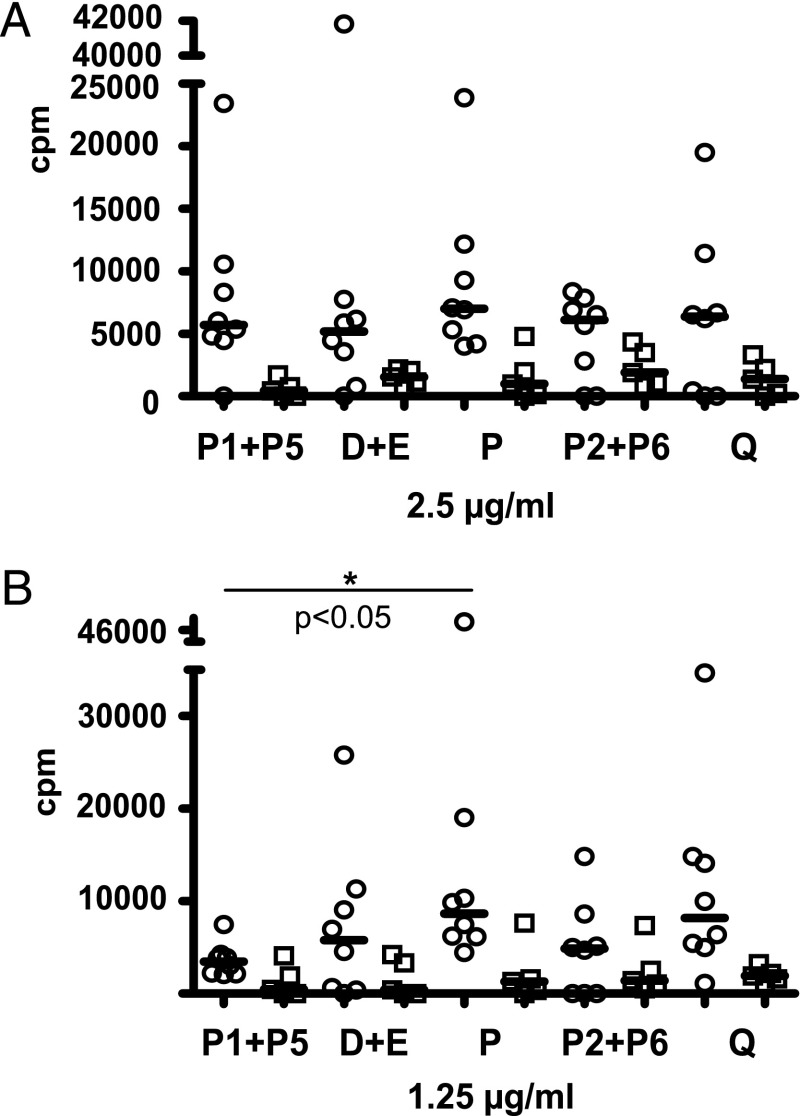

The four proteins D, E, P, and Q could be expressed as soluble proteins (>1 mg/l culture; Fig. 2A) and purified to homogeneity (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Coomassie blue–stained SDS-PAGE containing purified mosaic proteins. The recombinant mosaic proteins D, E, P, and Q (1 μg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. Molecular masses are indicated in kilodaltons (kDa).

Fig. 2C shows the results of the quantitative IgE-reactivity testing for combinations of D+E+Q and P+Q. These two combinations covered the Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, and Phl p 6 sequence in three (D+E+Q) or in two proteins (P+Q). The mix of D+E+Q, as well as of P+Q, was compared with mixtures of Phl p 1+Phl p 2+Phl p 5+Phl p 6 for quantitative IgE reactivity in 57 patients (Fig. 2C and Supplemental Table I). Both mixtures, D+E+Q and P+Q, showed a >60% reduction of IgE reactivity compared with the four wild-type allergens, which was significant for both combinations of hypoallergens (p < 0.01; Fig. 2C). Also for the combination D+E, as well as for P and Q, a significant reduction of IgE reactivity compared with the corresponding wild-type allergens (i.e., Phl p 1+Phl p 5, Phl p 2+Phl p 6) was observed (Fig. 2C). Sera from nonatopic individuals and an allergic patient not sensitized to grass pollen (patients 73 and 74; Supplemental Table I) showed no IgE reactivity to any of the proteins (cpm values ranged between 3 and 35 cpm).

The structural analysis of E and P by circular dichroism showed that these proteins exhibited a considerable amount of α-helical secondary structure that was similar to the mix rPhl p 1 and rPhl p 5 (Fig. 4A). By contrast, the CD spectrum of D was indicative of a more unfolded protein. Likewise, the spectrum of Q was typical for an unfolded protein, which differed from the CD spectrum of the P6b-P2M hybrid earlier described (22). The mix of Phl p 2 and Phl p 6 showed a CD spectrum indicative of mixed α-helical and β-sheet secondary structure (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

CD-spectra of the purified mosaic molecules D, E, and P and of a mixture of the recombinant wild-type allergens Phl p 1+5 (A), and the hybrid Q and a Phl p 2+6 mix (B). Results are shown as the mean residue ellipticity (y-axis) at a given wavelength (x-axis).

Mosaic molecules D, E, P, and Q show reduced allergenic activity and preserved T cell reactivity

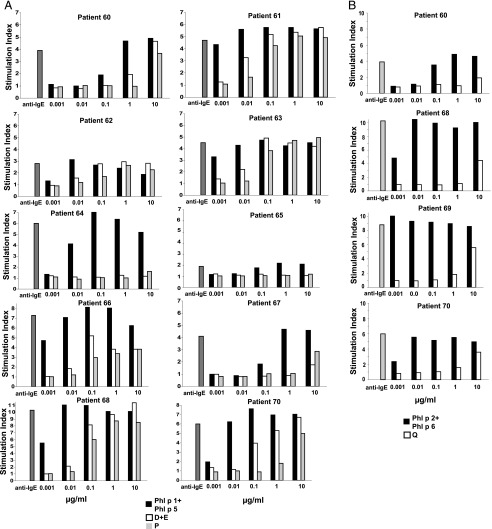

The evaluation of the allergenic activity of the mosaic molecules was performed by basophil activation testing in grass pollen–allergic patients (26). In a first set of experiments, the molecule P or a mixture of the molecules D+E were compared with mixtures of the wild-type allergens Phl p 1 and Phl p 5. Leukocytes from 10 grass pollen–allergic patients were challenged with increasing concentrations of these proteins, and activation-induced CD203c upregulation was determined by FACS analysis (Fig. 5A). Dose-dependent basophil activation was observed in response to the mixture of the wild-type allergens Phl p 1 and Phl p 5 in all patients tested, but the individual sensitivity of basophils varied from patient to patient (Fig. 5A, black bars). Certain patients showed maximal upregulation already at a concentration of 0.01 μg/ml of the Phl p 1/Phl p 5 mixture (e.g., patient 61), whereas in other patients, basophils were less sensitive and showed maximal activation at 1 μg/ml of the Phl p 1+Phl p 5 mixture (e.g., patient 67). In most patients, a reduction of allergenic activity of D+E, P versus Phl p 1+Phl p 5 of at least 100-fold was observed (i.e., patients 61, 66, 67, 70, 64, 68, 62, and 65) and in two patients the reduction was ∼10-fold (i.e., patients 63 and 60).

FIGURE 5.

Reduced allergenic activity of mosaics D, E, P, and Q compared with wild-type allergens. CD203c expression on basophils of grass pollen–allergic patients after stimulation with mixtures of rPhl p 1 and rPhl p 5, or a mixture of D and E, or P (A), or with a mixture of rPhl p 2 and rPhl p 6, or Q (B) is shown. Heparinized blood samples were incubated with different concentrations (0.001–10 μg/ml) of the recombinant allergens or mosaics, or an anti-IgE Ab (anti-IgE; x-axis), and analyzed for upregulation of the surface marker CD203c on basophils by flow cytometry. Allergen-induced upregulation of CD203c and CD63 was calculated from MFIstim and MFIcontrol and expressed as stimulation index (MFIstim/MFIcontrol). The stimulation indices are displayed on the y-axis.

The reduction of allergenic activity of the molecule Q was even stronger than that of P or the mixture of D+E. In all but one patient (i.e., patient 60: 0.1 μg/ml), the mixture of wild-type Phl p 2 and Phl p 6 induced an activation of effector cells already at a concentration of 0.001 μg/ml (Fig. 5B, black bars), whereas the mosaic protein Q did not induce basophil activation except for the highest concentration of 10 μg/ml (Fig. 5B, white bars). These data indicate a reduction of allergenic activity of Q versus the mix of Phl p 2 + Phl p 6 of >100-fold.

Although the allergenic activity of the mosaic molecules was reduced, most of the T cell epitope sequences of the wild-type Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, and Phl p 6 allergens were preserved (Supplemental Table III). In vitro proliferation experiments with PBMC isolated from eight grass pollen–allergic patients showed that the mosaic molecules D+E, P, and Q induced a comparable T cell proliferation in PBMCs of all patients as a mixture of Phl p 1+Phl p 5 and a mixture of Phl p 2+Phl p 6, respectively (Fig. 6). Only P induced a significantly higher proliferation than the mix of Phl p 1+Phl p 5 at 1.25 μg/ml. PBMCs from two allergic patients not sensitized to grass pollen allergens and from three healthy individuals also proliferated in response to the wild-type allergens and mosaic proteins, although at lower levels than PBMCs from allergic patients (Fig. 6). Cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IFN-γ) secreted by PBMCs from grass pollen–allergic patients in response to Phl p 2+Phl p 6 and Q showed no significant differences (Supplemental Fig. 1). There was also no difference between cytokine responses to the mix of Phl p 1 and Phl p 5 compared with P (Supplemental Fig. 1). PBMCs from nonallergic and allergic patients without grass pollen allergy mounted comparable cytokine levels in response to wild-type allergens and mosaic proteins (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Immunization with mosaic molecules D, E, P, and Q induces higher levels of allergen-specific IgG Abs than immunization with wild-type allergens or with the registered grass pollen allergy vaccine, Pollinex

The ability of the mosaic molecules to induce IgG Ab responses to the wild-type allergens was investigated in different animal models. Immunization of BALB/c mice with the mosaics D+E or P induced a stronger Phl p 1– and Phl p 5–specific IgG1 Ab response than with the mixture of the wild-type allergens Phl p 1+Phl p 5, although the differences did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 7A, 7B). Remarkably, Phl p 2 failed to induce an IgG response, whereas immunization with Q led to robust Phl p 2– and Phl p 6–specific IgG1 Ab responses (Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 7.

Allergen-specific IgG1 Ab responses to D, E, P, and Q in BALB/c mice. Sera from BALB/c mice, immunized either with a mix of Phl p 1 + Phl p 5 (P1+P5), Phl p 2 + Phl p 6 (P2+P6), the mosaic molecules D+E, P, or Q, were tested for Phl p 1– and Phl p 5–specific IgG1 Abs (A and B) and Phl p 2– and Phl p 6–specific IgG1 (C) by ELISA. Serum samples were taken before immunization (day 0) and at days 28 and 56. OD values are shown on the y-axis. *p < 0.05.

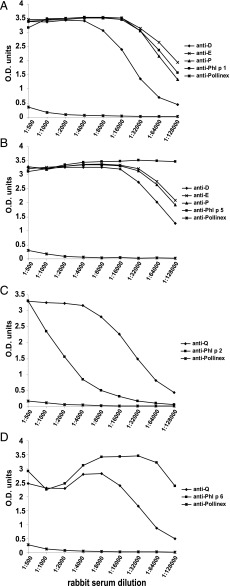

Immunization of rabbits with the mosaics demonstrated that D, E, and P were able to induce Phl p 1–, and Phl p 5–specific IgG Ab responses comparable with the wild-type allergens Phl p 1 and Phl p 5 (Fig. 8A, 8B). Hybrid Q induced both a Phl p 2– and a Phl p 6–specific IgG response. The Phl p 2–specific IgG responses induced with Phl p 2 were very low, whereas again Q induced higher Phl p 2–specific IgG levels. To compare the mosaic-induced Ab levels with a commercially available grass pollen vaccine based on natural allergen extract, we immunized rabbits with the grass pollen vaccine Pollinex Quattro plus according to the recommendation of the manufacturer. We found that Pollinex induced only weak Phl p 1–, Phl p 2–, Phl p 5–, and Phl p 6–specific Ab responses, which were only detectable in the lowest serum dilution of 1:500 (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Titration of antisera from rabbits immunized with D, E, P, Q, Pollinex, Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, or Phl p 6. IgG Ab responses to Phl p 1 (A), Phl p 5 (B), Phl p 2 (C), and Phl p 6 (D) were measured by ELISA over a broad range of dilutions (x-axes). OD values are given on the y-axes.

Antisera obtained by immunization with hypoallergenic mosaics inhibit allergic patients’ IgE binding to natural grass pollen allergens and allergen-induced basophil degranulation, as well as airway hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of grass pollen allergy

Next, we investigated the ability of IgG Abs induced by the mosaic molecules D, E, P, and Q to inhibit grass pollen–allergic patients’ IgE binding to natural grass pollen allergens. We used either a timothy grass pollen extract or a mixture of grass pollen extracts from five different grasses. In ELISA inhibition experiments, we preincubated either ELISA plate-bound natural timothy grass pollen extract or the five-grass mix with a mixture of rabbit anti-P and -Q antiserum, or a mixture of anti-D+E, and Q antiserum, or anti–Phl p 1, –Phl p 2, –Phl p 5, and –Phl p 6 antisera, or anti-Pollinex antiserum. The D-, E-, P-, and Q-induced rabbit IgG Abs inhibited the IgE binding of 10 grass pollen–allergic patients to the natural timothy grass pollen allergens up to 88%; preincubation with the WT-specific IgG resulted in 90% inhibition. Pollinex-induced IgG Abs showed a mean inhibition of only 15.8% (Table I). Mosaic-induced Abs also interfered with IgE-binding to the homologous allergens from other grasses, achieving inhibitions of 76% with anti-D, -E, and -Q antisera, 73% with anti-P and anti-Q antisera, and 75% with anti–Phl p 1, –Phl p 2, –Phl p 5, and –Phl p 6 antisera. The lowest inhibition was measured with Pollinex-induced IgG (14%; Table I).

Table I. Inhibition of patients’ IgE binding to natural grass pollen allergens by vaccine-induced Abs.

| % Inhibition after Preincubation of Timothy Grass Pollen Extract with Rabbit Antisera against: |

% Inhibition after Preincubation of Grass Pollen Extracts from Five Grasses with Rabbit Antisera against: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient No. | D+E+Q | P+Q | Phl p 1,Phl p 2, Phl p 5, Phl p 6 | Pollinex | D+E+Q | P+Q | Phl p 1,Phl p 2, Phl p 5, Phl p 6 | Pollinex |

| 58 | 87.2 | 86.5 | 91.9 | 31.3 | 72.8 | 68.9 | 74.9 | 24.1 |

| 59 | 93.4 | 92.1 | 95.2 | 12.8 | 77.4 | 73.6 | 77.1 | 19.1 |

| 60 | 89.8 | 89.2 | 91.6 | 0.0 | 79.4 | 77.6 | 78.7 | 1.7 |

| 61 | 89.3 | 89.5 | 91.6 | 2.6 | 78.0 | 78.6 | 83.1 | 7.9 |

| 62 | 85.0 | 83.2 | 86.3 | 16.3 | 78.0 | 74.7 | 77.0 | 15.6 |

| 65 | 78.3 | 77.3 | 76.4 | 18.1 | 71.8 | 69.1 | 67.6 | 6.7 |

| 66 | 94.8 | 94.3 | 96.7 | 27.5 | 79.3 | 74.4 | 78.6 | 21.4 |

| 68 | 86.5 | 84.3 | 91.7 | 22.1 | 71.2 | 61.5 | 65.0 | 21.1 |

| 69 | 87.7 | 85.9 | 87.4 | 26.2 | 81.4 | 79.1 | 77.5 | 11.0 |

| 70 | 88.2 | 87.1 | 91.1 | 0.7 | 77.9 | 74.5 | 71.1 | 11.3 |

| Mean | 88.0 | 87.0 | 90.0 | 15.8 | 76.7 | 73.2 | 75.0 | 14.0 |

| SD | 4.5 | 4.8 | 5.7 | 11.5 | 3.5 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 7.4 |

The in vivo effect of antisera raised against the mosaic molecules D, E, P, and Q was investigated in a murine model of grass pollen allergy. Mice were sensitized to Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, and Phl p 6 (Fig. 9A and 9B) and developed an IgE response to the allergens on day 25 (Fig. 9C and 9E). Antisera specific for D+E+Q or P+Q, but not an antiserum raised against an irrelevant protein (Fig. 9A, 9B, and 9D), suppressed IgE reactivity to Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, and Phl p 6 of sensitized mice (Fig. 9C). Furthermore, a suppression of Phl p 1–, Phl p 2–, Phl p 5–, and Phl p 6–induced basophil degranulation and airway hyperresponsiveness was observed in mice treated with mosaic protein-induced Abs, but not in mice having received an irrelevant antiserum (Fig. 9E and 9F).

FIGURE 9.

Murine model for treatment of grass pollen allergy. (A) Groups of mice were sensitized to a mix of grass pollen allergens Phl p 1, Phl p 2, Phl p 5, and Phl p 6, treated with antisera or PBS as indicated and challenged with the allergen mix (+) or PBS. (B) Schematic overview of experimental schedule. (C) Detection of grass pollen allergen–specific IgE (y-axis) in mouse sera of groups 1–4 on days 0, 25, and 26 (x-axis) by ELISA. (D) ELISA measurement of grass pollen allergen–specific rabbit IgG (y-axis) in mouse sera of groups 1–4 on days 0, 25, and 26 (x-axis). (E) β-Hexosaminidase release of RBL cells (y-axis) loaded with mouse sera of groups 1–4 from days 25 and 26 (x-axis) and challenged with the allergen mix. (F) Airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) was assessed by whole-body plethysmography. Penh (y-axis) is shown at increasing methacholine concentrations (8, 16, 32, 64 mg/ml; x-axis) for groups 1–4 as means ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Discussion

Grass pollen allergies represent a global health problem in industrialized countries. Grass pollen allergen–specific immunotherapy based on allergen extracts is a widely used treatment option but needs further improvement. In this article, we report the molecular evolution of a hypoallergenic vaccine for the treatment of grass pollen allergy, which is based on the combination of fragments derived from the four major timothy grass pollen allergens within two recombinant mosaic proteins. The major timothy grass pollen allergens, Phl p 1 and Phl p 5, and Phl p 2 and Phl p 6, were previously identified as the major elicitors of grass pollen allergy (17–19). These four allergens were shown to be sufficient for grass pollen–specific immunotherapy in a clinical trial (20), and fusion proteins combining these allergens have been engineered to facilitate vaccine production and to increase the poor immunogenicity in particular of the Phl p 2 allergen (25, 32). Because vaccines based on wild-type–like recombinant allergens may induce severe IgE-associated anaphylactic side effects, hypoallergenic variants of each of these allergens have been produced (21, 33, 34; M. Focke and R. Valenta, unpublished observations). Our first attempt of fusing the four hypoallergens in the form of a single hypoallergenic mosaic protein designated A (Figs. 1 and 2A) surprisingly showed that the IgE reactivity of these molecules was not sufficiently reduced.

We therefore embarked on a systematic breeding approach toward a hypoallergenic vaccine and assembled a battery of different allergen-derived fragments. In total, 10 Phl p 1– and Phl p 5–derived molecules and 5 Phl p 2– and Phl p 6–derived molecules were prepared based on a mosaic approach and analyzed for their biochemical and immunological properties, whereby some interesting and surprising observations were made. For example, we found that per se hypoallergenic allergen fragments showed varying IgE reactivity depending on how they were arranged within a molecule (Figs. 1 and 2A). For example, mosaic C showed strong IgE reactivity, whereas the IgE reactivity of E was strongly reduced.

As a result of the systematic breeding approach, the primary sequence of the four major grass pollen allergens could be packed into two hypoallergenic proteins, P and Q, which showed a reduction of IgE reactivity and allergenic activity. Importantly, upon immunization, P and Q induced higher levels of allergen-specific IgG than the wild-type allergens and in particular against the poorly immunogenic Phl p 2 allergen.

Importantly, we found that P and Q also induced higher grass pollen allergen–specific IgG Abs upon immunization of rabbits as compared with a registered grass pollen allergy vaccine (i.e., Pollinex Quattro Plus) based on natural grass pollen allergen extract adsorbed to the potent adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A. IgG Abs induced by immunization with P and Q also more strongly inhibited IgE binding to natural timothy grass pollen allergens and even toward a five-grass pollen allergen mix than Abs induced with Pollinex Quattro Plus. Moreover, antisera raised against the mosaic molecules inhibited grass pollen allergen–induced basophil degranulation and airway hyperresponsiveness in a murine model. The latter effect may be explained by the competition of mosaic-specific IgG Abs, which interfered with the allergen–IgE interaction. The induction of allergen-specific IgG toward major IgE epitopes by the mosaic proteins P and Q may be due to the fact that the fragments in the mosaic proteins were designed to contain sequences that were known to either be part of IgE epitopes or to induce IgG toward the IgE binding sites (Supplemental Table III). Because the allergenic activity of P and Q was reduced, we believe that the two components can be used to formulate a grass pollen vaccine that will induce robust allergen-specific IgG responses with few injections and fewer negative side effects than currently available vaccines. In fact, safety and efficacy of vaccination with recombinant hypoallergens has been demonstrated in several clinical trials for allergen sources containing one major allergen (i.e., Bet v 1 from birch pollen), and a hypoallergenic Bet v 1 folding variant was shown to be clinically effective up to phase III SIT trials in patients (35).

Results from lymphoproliferation experiments indicate that the grass pollen allergen–specific T cell epitopes have been maintained in the hypoallergenic mosaic proteins. In fact, Supplemental Table III shows that the fragments used to build the mosaic molecules P and Q contained most of the allergen-specific T cell epitopes in an intact form. It should therefore also be possible to use P and Q for the induction of T cell tolerance in grass pollen–allergic patients as it was described for cat allergy (36) or oral tolerance induction (37).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge technical help by Karin Fleischmann regarding the expression and purification of proteins.

This work was supported by Austrian Science Fund Grants P23350-B11, F4605, and F4610, and by a research grant from Biomay AG (Vienna, Austria).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

- HSA

- human serum albumin

- MFI

- mean fluorescence intensity

- MFIcontrol

- MFI obtained with control cells

- MFIstim

- MFI obtained with stimulated cells

- SIT

- allergen-specific immunotherapy.

Disclosures

R.V. serves as a consultant for Biomay AG and Thermo Fisher (Uppsala, Sweden). A.N. is an employee of Biomay AG. The other authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Panzner P., Vachová M., Vítovcová P., Brodská P., Vlas T. 2014. A comprehensive analysis of middle-European molecular sensitization profiles to pollen allergens. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 164: 74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galant S., Berger W., Gillman S., Goldsobel A., Incaudo G., Kanter L., Machtinger S., McLean A., Prenner B., Sokol W., et al. Allergy Skin Test Project Team 1998. Prevalence of sensitization to aeroallergens in California patients with respiratory allergy. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 81: 203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suphioglu C., Singh M. B., Taylor P., Bellomo R., Holmes P., Puy R., Knox R. B. 1992. Mechanism of grass-pollen-induced asthma. Lancet 339: 569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akdis M. 2009. Immune tolerance in allergy. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 21: 700–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durham S. R., Walker S. M., Varga E. M., Jacobson M. R., O’Brien F., Noble W., Till S. J., Hamid Q. A., Nouri-Aria K. T. 1999. Long-term clinical efficacy of grass-pollen immunotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 341: 468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Möller C., Dreborg S., Ferdousi H. A., Halken S., Høst A., Jacobsen L., Koivikko A., Koller D. Y., Niggemann B., Norberg L. A., et al. 2002. Pollen immunotherapy reduces the development of asthma in children with seasonal rhinoconjunctivitis (the PAT-study). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 109: 251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noon L. 1911. Prophylactic inoculation against hey fever. Lancet 177: 1572–1573. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winther L., Arnved J., Malling H. J., Nolte H., Mosbech H. 2006. Side-effects of allergen-specific immunotherapy: a prospective multi-centre study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 36: 254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Focke M., Marth K., Flicker S., Valenta R. 2008. Heterogeneity of commercial timothy grass pollen extracts. Clin. Exp. Allergy 38: 1400–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mothes N., Heinzkill M., Drachenberg K. J., Sperr W. R., Krauth M. T., Majlesi Y., Semper H., Valent P., Niederberger V., Kraft D., Valenta R. 2003. Allergen-specific immunotherapy with a monophosphoryl lipid A-adjuvanted vaccine: reduced seasonally boosted immunoglobulin E production and inhibition of basophil histamine release by therapy-induced blocking antibodies. Clin. Exp. Allergy 33: 1198–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marsh D. G., Lichtenstein L. M., Campbell D. H. 1970. Studies on “allergoids” prepared from naturally occurring allergens. I. Assay of allergenicity and antigenicity of formalinized rye group I component. Immunology 18: 705–722. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas W. R. 2011. The advent of recombinant allergens and allergen cloning. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 127: 855–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valenta R., Ferreira F., Focke-Tejkl M., Linhart B., Niederberger V., Swoboda I., Vrtala S. 2010. From allergen genes to allergy vaccines. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28: 211–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linhart B., Valenta R. 2005. Molecular design of allergy vaccines. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 17: 646–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linhart B., Valenta R. 2012. Mechanisms underlying allergy vaccination with recombinant hypoallergenic allergen derivatives. Vaccine 30: 4328–4335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cromwell O., Häfner D., Nandy A. 2011. Recombinant allergens for specific immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 127: 865–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suphioglu C. 2000. What are the important allergens in grass pollen that are linked to human allergic disease? Clin. Exp. Allergy 30: 1335–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersson K., Lidholm J. 2003. Characteristics and immunobiology of grass pollen allergens. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 130: 87–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westritschnig K., Horak F., Swoboda I., Balic N., Spitzauer S., Kundi M., Fiebig H., Suck R., Cromwell O., Valenta R. 2008. Different allergenic activity of grass pollen allergens revealed by skin testing. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 38: 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jutel M., Jaeger L., Suck R., Meyer H., Fiebig H., Cromwell O. 2005. Allergen-specific immunotherapy with recombinant grass pollen allergens. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 116: 608–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ball T., Linhart B., Sonneck K., Blatt K., Herrmann H., Valent P., Stoecklinger A., Lupinek C., Thalhamer J., Fedorov A. A., et al. 2009. Reducing allergenicity by altering allergen fold: a mosaic protein of Phl p 1 for allergy vaccination. Allergy 64: 569–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linhart B., Mothes-Luksch N., Vrtala S., Kneidinger M., Valent P., Valenta R. 2008. A hypoallergenic hybrid molecule with increased immunogenicity consisting of derivatives of the major grass pollen allergens, Phl p 2 and Phl p 6. Biol. Chem. 389: 925–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valenta R., Duchene M., Ebner C., Valent P., Sillaber C., Deviller P., Ferreira F., Tejkl M., Edelmann H., Kraft D., Scheiner O. 1992. Profilins constitute a novel family of functional plant pan-allergens. J. Exp. Med. 175: 377–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verdino P., Keller W. 2004. Circular dichroism analysis of allergens. Methods 32: 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linhart B., Hartl A., Jahn-Schmid B., Verdino P., Keller W., Krauth M. T., Valent P., Horak F., Wiedermann U., Thalhamer J., et al. 2005. A hybrid molecule resembling the epitope spectrum of grass pollen for allergy vaccination. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 115: 1010–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hauswirth A. W., Natter S., Ghannadan M., Majlesi Y., Schernthaner G. H., Sperr W. R., Bühring H. J., Valenta R., Valent P. 2002. Recombinant allergens promote expression of CD203c on basophils in sensitized individuals. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 110: 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campana R., Vrtala S., Maderegger B., Jertschin P., Stegfellner G., Swoboda I., Focke-Tejkl M., Blatt K., Gieras A., Zafred D., et al. 2010. Hypoallergenic derivatives of the major birch pollen allergen Bet v 1 obtained by rational sequence reassembly. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 126: 1024–1031, e1–e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flicker S., Linhart B., Wild C., Wiedermann U., Valenta R. 2013. Passive immunization with allergen-specific IgG antibodies for treatment and prevention of allergy. Immunobiology 218: 884–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linhart B., Narayanan M., Focke-Tejkl M., Wrba F., Vrtala S., Valenta R. 2014. Prophylactic and therapeutic vaccination with carrier-bound Bet v 1 peptides lacking allergen-specific T cell epitopes reduces Bet v 1-specific T cell responses via blocking antibodies in a murine model for birch pollen allergy. Clin. Exp. Allergy 44: 278–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamelmann E., Schwarze J., Takeda K., Oshiba A., Larsen G. L., Irvin C. G., Gelfand E. W. 1997. Noninvasive measurement of airway responsiveness in allergic mice using barometric plethysmography. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 156: 766–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Padavattan S., Flicker S., Schirmer T., Madritsch C., Randow S., Reese G., Vieths S., Lupinek C., Ebner C., Valenta R., Markovic-Housley Z. 2009. High-affinity IgE recognition of a conformational epitope of the major respiratory allergen Phl p 2 as revealed by X-ray crystallography. J. Immunol. 182: 2141–2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linhart B., Jahn-Schmid B., Verdino P., Keller W., Ebner C., Kraft D., Valenta R. 2002. Combination vaccines for the treatment of grass pollen allergy consisting of genetically engineered hybrid molecules with increased immunogenicity. FASEB J. 16: 1301–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vrtala S., Focke M., Kopec J., Verdino P., Hartl A., Sperr W. R., Fedorov A. A., Ball T., Almo S., Valent P., et al. 2007. Genetic engineering of the major timothy grass pollen allergen, Phl p 6, to reduce allergenic activity and preserve immunogenicity. J. Immunol. 179: 1730–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mothes-Luksch N., Stumvoll S., Linhart B., Focke M., Krauth M. T., Hauswirth A., Valent P., Verdino P., Pavkov T., Keller W., et al. 2008. Disruption of allergenic activity of the major grass pollen allergen Phl p 2 by reassembly as a mosaic protein. J. Immunol. 181: 4864–4873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valenta R., Niederberger V. 2007. Recombinant allergens for immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 119: 826–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Worm M., Lee H. H., Kleine-Tebbe J., Hafner R. P., Laidler P., Healey D., Buhot C., Verhoef A., Maillère B., Kay A. B., Larché M. 2011. Development and preliminary clinical evaluation of a peptide immunotherapy vaccine for cat allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 127: 89–97, e1–e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Consortium of Food Allergy Research (CoFAR) 2012. Oral immunotherapy for treatment of egg allergy in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 367: 233–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.