Abstract

The overall chasm between those who need treatment for mental health and substance abuse (M/SU) and those who receive effective treatment consists of two, interrelated gaps: the research-to-practice gap and the treatment gap. Prior efforts to disseminate evidence-based practice (EBP) for M/SU have predominantly targeted the research-to-practice gap, by focusing efforts toward treatment providers. This article introduces direct-to-consumer (DTC) marketing that targets patients and caregivers as a complementary approach to existing dissemination efforts. Specific issues discussed include: rationale for DTC marketing based on the concept of push versus pull marketing; overview of key stakeholders involved in DTC marketing; and description of the Marketing Mix planning framework. The applicability of these issues to the dissemination of EBP for M/SU is discussed.

Keywords: direct-to-consumer, marketing, dissemination, implementation, mental health, substance abuse

One of the most pressing concerns facing our healthcare system today is the gap between those who need treatment and those who receive an effective intervention. While this gap is large across all areas of healthcare, few areas are characterized by a gap as complex and challenging as the fields of mental health and substance use treatment. In 2001, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) issued a seminal report titled Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, which proposed a comprehensive strategy to improve the quality of the U.S. healthcare system by taking into account both patient preferences and scientific findings about effective care (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Five years later, the IOM released a follow-up report titled, Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions, which adapted the recommendations in the 2001 report for mental and substance use (M/SU) treatment (Institute of Medicine, 2006). This report highlighted a myriad of ways in which M/SU treatments were distinct from general healthcare services including: increased stigma attached to M/SU diagnoses; more frequent coercion into treatment (especially for substance use conditions); less developed infrastructure for measuring quality; greater need for linkages across clinicians working with the same patient; and a more educationally diverse workforce. Recommendations of the report emphasized the need to engage multiple stakeholders, including practitioners, policy makers, and patients, in order to bridge the “quality chasm” in M/SU treatment (Institute of Medicine, 2006).

Since the publication of these IOM reports, there has been increased interest in elevating the reach and quality of M/SU treatment. This interest has been reflected in a number of federal initiatives to fund the dissemination and implementation (D&I) of effective interventions. The National Institute of Health (NIH) released a specific D&I program announcement in 2005 (PAR-06-039) and established a cross-NIH review committee to evaluate proposals. Multiple agencies within the NIH including the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Addiction (NIAAA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) have established strategic D&I priorities focused on increasing the utilization of effective interventions among diverse populations. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) has also funded a number of initiatives to translate research findings into practice, including the development of a national system of Addiction Technology Transfer Centers (ATTC) and the National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

An overarching goal of these federal initiatives is to address the quality chasm by promoting the use of research-tested psychological interventions, commonly referred to as “evidence based practice” (EBP). Efforts to increase the utilization of EBP can be conceptualized as targeting two related, yet distinct gaps. First, the gap between those treatment models that have the greatest evidentiary support and those delivered in practice, otherwise known as the “research-to-practice” or the “evidence to practice” gap (e.g., Bero et al., 1998; Lang, Wyer, & Haynes, 2007). And second, the gap between those individuals who need services and those who seek services in community settings, otherwise known as the “treatment gap” or “unmet need” (e.g., Demyttenaere et al., 2004; Kohn et al., 2004). These gaps represent two co-existing problems in our field, and addressing these gaps requires consideration of different target audiences and strategies. Given the size and scope of the quality chasm, it is imperative that our field address both of these gaps simultaneously in order to increase both the quality and utilization of M/SU treatment.

The objective of the current article is to introduce direct-to-consumer (DTC) marketing as a potential complement to traditional D&I efforts. Similar to prior reviews (see McHugh & Barlow, 2010) this article does not debate the merit of identifying or delivering EBP, but rather focuses on prior and potential efforts to expand the reach of EBP. This article consists of two components: 1) a brief review of how prior D& I efforts have addressed the two gaps that comprise the quality chasm; and 2) an introduction to key terms and concepts associated with DTC marketing, with emphasis on how DTC marketing is uniquely well-suited to address the treatment gap.

The Quality Chasm: A Tale of Two Gaps

Gap 1: The Research-to-Practice Gap

In the M/SU treatment system, efforts to close the research-to-practice gap (Gap 1) focus on elevating the standard of care offered to those individuals who seek treatment. Estimates from the most recent National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NHSUD; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013a) suggest that between 10 and 15% of Americans over the age of 12 receive M/SU treatment annually. Of those Americans who seek M/SU treatment, only a small proportion is likely to receive care that is consistent with current EBP guidelines. An early review of studies from 1992–2000 assessed the implementation of clinical treatment guidelines for a range of psychiatric conditions and found adequate rates of adherence in only 27% of naturalistic investigations (Bauer, 2002). Factors contributing to poor adherence to EBP guidelines have been the subject of many excellent reviews and qualitative studies (e.g., Addis, Wade, & Hatgis, 1999; Miller, Sorensen, Selzer, & Brigham, 2006; Pagoto et al., 2007). Indeed, one early review documented 293 unique barriers to clinicians’ adherence to EBP guidelines across medical disciplines (Cabana et al., 1999). More recent studies have continued to document departures from EBP guidelines across M/SU conditions as diverse as: ADHD (Rushton, Fant, & Clark, 2004), depression and anxiety (Smolders et al., 2009), bipolar disorder (Dennehy, Bauer, Perlis, Kogan, & Sachs, 2007), and schizophrenia (Drake, Bond, & Essock, 2009).

Even when community agencies offer EBP to patients, it is unclear the extent to which these agencies deliver the interventions with fidelity. As an example, a recent survey of practices in the state of Washington (McBride, Voss, Mertz, Villaneuva, & Smith, 2007) found that 73% of mental health agencies reported using cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) as an EBP, but only 35% of the agencies used any form of outside accreditation and only 43% reported monitoring or assessing fidelity in any way. Furthermore, it is well-documented that agencies that commit to implementing EBP face significant challenges sustaining the implementation of EBP over the longer-term. In a recent review, Stirman and colleagues (2012) identified only 10 methodologically rigorous studies that evaluated the sustainability of M/SU interventions after an initial period of implementation or funding. Among these 10 studies, partial sustainability (n = 7 studies) was far more common than full continuation of the intervention (n = 3 studies), even in cases when full implementation had been achieved initially. These results are consistent with literature documenting a multitude of challenges sustaining the implementation of EBP at both the individual clinician (e.g., awareness, competence, willingness to adopt an intervention) and the organizational (e.g., staff turnover, lack of leadership support, variable standards for credentialing, and lack of resources to support ongoing training) levels (see Haynes & Haines, 1998; Virani, Lemieux-Charles, Davis, & Berta, 2008).

Over the past few decades, recognition of the myriad challenges bridging Gap 1 has led to an exponential increase in research publications about the research-to-practice gap. Common themes in the literature focused specifically on Gap 1 have included: development of conceptual models and frameworks to guide EBP transfer (Tabak, Khoong, Chambers, & Brownson, 2012); identification of barriers and facilitators to adapting EBP (Haynes & Haines, 1998; Miller et al., 2006; Pagoto et al., 2007); assessment of provider and agency interest in EBP (Aarons, 2004; McGovern, Fox, Xie, & Drake, 2004); evaluation of training and implementation strategies (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Miller, Yahne, Moyers, Martinez, & Pirritano, 2004; Sholomskas et al., 2005); and effectiveness studies testing EBP delivered by community practitioners (Dennis et al., 2004; Drake et al., 2001; Wells, Saxon, Calsyn, Jackson, & Donovan, 2010). Federal D&I initiatives have also invested significant financial resources directly toward Gap 1. For instance, NIDA’s Clinical Trial Network was created to promote partnerships between researchers and practitioners in order to “validate treatment interventions that fulfill the practical needs of community-based drug abuse treatment programs” (Tai et al., 2010). In the same vein, SAMSHA’s ATTCs were formed to enhance the development and training of an addictions workforce able to deliver EBP (Condon, Miner, Balmer, & Pintello, 2008).

Gap 2: The Treatment Gap

Relative to Gap 1, Gap 2 has been the focus of significantly less research and funding. The 2012 NHSUD estimated that 11.5 million American adults (4.9% of the population) had an unmet need for mental health treatment and that 16.8 million (6.5% of the population) had an unmet need for substance use treatment (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013a). In the 2012 NHSUD, two of the five most common reasons for failing to seek treatment reported by those with an unmet need for M/SU treatment were: belief that problems can be handled without treatment and lack of knowledge about where to go for help. These reasons highlight the need to increase patient awareness of the general benefits of treatment and the specific benefits of EBP. Furthermore, Gap 2 is most pronounced among underrepresented populations such as women, racial and ethnic minorities, and economically disadvantaged families (Kataoka, Zhang, & Wells, 2002; Mulvaney-Day, DeAngelo, Chen, Cook, & Alegría, 2012; Sherbourne, Dwight-Johnson, & Klap, 2001; Wells, Klap, Koike, & Sherbourne, 2001), suggesting that targeted outreach is especially important for these groups.

Recent years have seen the emergence of initiatives to bridge Gap 2, many of which have focused on training allied health professionals to increase the identification of M/SU patients. One common strategy has been to integrate M/SU assessment and brief intervention into a variety of allied health care settings, including primary care practices, Level I trauma centers, schools, courts, and detention centers/prisons. Integration efforts have been promoted through programs such as: routine M/SU screening (e.g., Fiellin, Reid, & O'Connor, 2000; Goldberg et al., 1997; Weist, Rubin, Moore, Adelsheim, & Wrobel, 2007); enhanced training in M/SU assessment (e.g., Corrigan, Steiner, McCracken, Blaser, & Barr, 2001; Ewan & Whaite, 1982) and co-located M/SU treatments (e.g., Craven & Bland, 2006). In the substance abuse field, Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is a widely recommended protocol to increase the detection and treatment of individuals at risk of developing substance use disorders (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013b).

While the aforementioned efforts are conceptually well suited to address Gap 2, it is unclear whether they have had any measurable influence on the treatment-seeking gap, especially as it pertains to psychological interventions. Although the overall proportion of American adults who received any mental health treatment in the past year has increased over the past 10 years (e.g., 13.0% of adults in 2002 vs. 14.5% in 2012), this increase was predominantly driven by a rise in prescription medications. The proportion of American adults receiving therapy or other outpatient treatment has actually decreased (e.g., 7.4% of adults in 2002 vs. 6.6% in 2012; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003, 2013a). Meanwhile, overall rates of substance use treatment utilization have held steady from 10.3% of individuals with a diagnosable substance use disorder in the 2002 NSDUH survey to 10.8% in the 2012 survey.

Taken together, these data demonstrate the need to expand the scope of traditional D&I efforts for M/SU psychological treatments, with a particular need for strategies that target Gap 2. Collectively, prior efforts to bridge the quality chasm have shared a key commonality: initiatives have predominantly focused on practitioners – both in specialty M/SU and allied health services – as the providers of service. As noted in recent commentary by Gallo, Comer, and Barlow (2013), the dominant model for advancing the use of EBP has been a “top-down” approach, reflecting an implicit assumption that the primary barrier to the use of EBP is provider knowledge, training, and competency. While this barrier is certainly of paramount importance, efforts that focus solely on practitioners do not address many of the systemic issues associated with Gap 2, such as lack of knowledge about and interest in EBP. DTC marketing approaches that directly target M/SU patients and caregivers have the potential to address these systemic barriers, and represent a complementary paradigm to traditional D&I approaches. The following section introduces the rationale for DTC marketing as an approach to target Gap 2. Subsequent sections identify the key stakeholders involved in DTC marketing initiatives and introduce a common planning framework called the “Marketing Mix.”

Direct-to-Consumer Marketing: A Complementary Approach

Rationale: Need for Two Types of Marketing

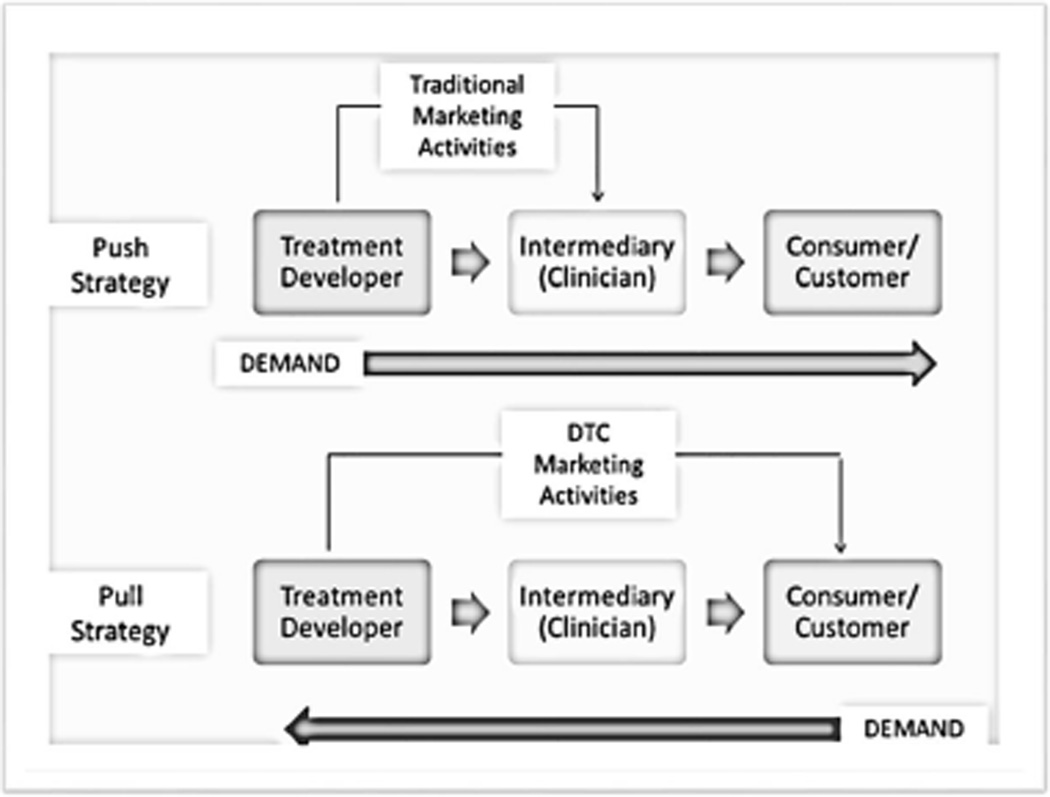

DTC marketing is typically defined as marketing a product or service directly from the developer to the consumer (or the customer, as described in the Key Stakeholders section). The rationale for DTC marketing is based on the concept of push versus pull marketing (Dowling, 2004). These distinct marketing strategies are presented in Figure 1 and described in the following paragraphs. Of note, these descriptions could be applied interchangeably to the marketing of products (e.g., packaged foods, clothes, cleaning products) or services, (e.g., therapy, insurance, house cleaning). Given this article’s focus on M/SU treatments, the language has been tailored to the marketing of services.

Figure 1.

Push versus Pull Strategies to Market Treatment. Note: DTC = direct to consumer or direct to customer

A push strategy is an approach designed to increase the consumer’s awareness of the service at the point of sale (e.g., the time when the service is being purchased). As depicted in Figure 1, one of the most common push tactics is directing marketing efforts (or “pushing” the service) to an intermediary, who then distributes the specific service to the end user. With regards to M/SU treatment, the typical approach of encouraging practitioners (the intermediaries) to deliver EBP would be defined as a push strategy, since this approach increases the likelihood that a patient who comes into contact with the treatment system will be offered EBP. Essentially, these efforts attempt to address Gap 1 by “bringing EBP to the patient.” Push strategies are particularly well-suited for services that consumers wouldn’t know to request (Buchanan, 2014). Assuming that there is limited awareness of EBP among potential M/SU patients, push tactics are therefore a vital component of a comprehensive marketing strategy.

By contrast, a pull marketing strategy involves “bringing the patient to EBP.” The objective of a pull strategy is to get the consumer to seek out the service (or “pull” the service from the developer) more actively. As shown in Figure 1, a common pull tactic is to direct marketing efforts toward the end user of a specific service. Efforts to utilize social media to increase consumer awareness and generate word-of-mouth referrals are also defined as pull strategies. In the M/SU field, organizations such as the International OCD Foundation, the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, and the American Psychological Association have recently used pull strategies by creating informational websites about EBP for the general public. In a recent piece in Behavior Therapy, Szymanski (2012) reported that the International OCD Foundation has started using multiple DTC marketing strategies including educational programming (e.g., web sites, conferences, newsletters, training), public awareness campaigns, and development of patient support networks. By increasing patient’s awareness of OCD and evidence-based guidelines, the hope is that strategies such as these encourage patients to seek out or “pull” EBP through the M/SU treatment system, thereby potentially addressing Gap 2.

While there is some debate about the specific benefits of push versus pull marketing, there is generally consensus that the most successful marketing initiatives incorporate both strategies (Kibilko, 2013). As an example, the marketing of psychiatric medications demonstrates a strategy that evolved to incorporate both push and pull strategies (Lamb, Hair Jr, & McDaniel, 2010). Initially, pharmaceutical companies used a push approach by having pharmaceutical sales representatives target their marketing of antidepressants, for example, directly to primary care doctors and psychiatrists. The goal of this approach was to have these physicians “push” the prescriptions to the patients. After the Food and Drug Administration released guidance for the advertising of medication in 1997 (see Ventola, 2011), pharmaceutical companies began using pull approaches by using mass media to market their medications directly to patients. The common tagline, “ask your doctor about…” is a classic example of a pull approach, since these statements are intended to have patients actively request or “pull” certain drugs from their physicians. To date, the combination of both pull and push approaches has been extremely lucrative for the pharmaceutical industry, with every $1.00 spent on advertising translating to approximately $4.20 of increased sales across the industry (Porter, 2011). Furthermore, studies suggest that the pharmaceutical industry’s integrated marketing approach has been associated with change in both patient treatment-seeking behavior (requesting the advertised medication) and provider prescribing behavior (increased likelihood of offering the advertised medication; see Gallo et al., 2013). Following this logic, integrated approaches that capitalize on both push and pull marketing, through a simultaneous focus on both Gap 1 and Gap 2, could serve to expand the scope of traditional D&I efforts for M/SU treatment.

Key Stakeholders

In order to use DTC marketing effectively to increase pull demand and address Gap 2, it is important to have a foundational understanding of the various stakeholders involved in marketing initiatives. As noted previously, DTC marketing is defined as marketing a service straight from the developer to the consumer (or the customer), without the use of any intermediaries. Each of the terms represented in italics represents a different stakeholder with different objectives and interests. Definitions of these terms and other key stakeholders are provided in the following paragraphs.

First and foremost, DTC marketing requires identification of the consumer. The consumer is typically defined as the end user of the service, or the individual who actively consumes the service. While the consumer is always a critical stakeholder, the consumer is not always the customer – defined as the person who researches, selects, and purchases (or pays for) the service. These terms are often used indiscriminately, but they represent two potentially distinct audiences for marketing. For instance, in the case of an adult seeking individual therapy for depression, the adult is likely both the consumer and the customer. By contrast, in the case of an adolescent seeking individual therapy for depression, the adolescent is likely to be the primary consumer, but is not necessarily the customer. It is well-established that the adolescent’s parent or caregiver is likely to be the customer who researches, finances, and manages the adolescent’s participation in treatment (see Kazdin, Holland, & Crowley, 1997; Nock & Ferriter, 2005). If the goal of a marketing initiative is to encourage patients (and associated caregivers) to seek out a specific type of M/SU treatment, then the customer who researches and selects the treatment is perhaps the most critical target audience. For the purposes of promoting M/SU treatment, “direct-to-customer” marketing is then at least as important as “direct-to-consumer” marketing.

Other important stakeholders include: developers, intermediaries and influencers. The developer is the creator of the service, while an intermediary is the party who takes the service created by the developer and delivers it to the end user. With regard to M/SU treatment, the primary developers are those who create the interventions and the primary intermediaries are those practitioners who deliver the interventions. Influencers are then individuals whose opinions are valued by the customer and who play a vital role in generating word-of-mouth treatment referrals. Influencers for adult M/SU treatment might include, but not be limited to: primary care practitioners (e.g., family practice doctors, obstetricians and gynecologists, internal medicine doctors), nurses, emergency department doctors, insurance agencies who recommend specific “in-network” providers, and counselors located within educational or vocational settings. Influencers for youth treatment would include many of the aforementioned individuals along with an array of other individuals who come into contact with youth in an educational and/or extracurricular capacity (e.g., school counselors, school administrators, sports coaches, extracurricular club advisors, etc.). Reflecting a focus on push marketing, prior efforts to close the quality chasm in M/SU treatment have predominantly focused on the relationship between developers and intermediaries, with significantly less attention invested toward customers, consumers, and influencers.

Division 53 (Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology) of the American Psychological Association has created an informational website about EBP models (effectivechildtherapy.com) that targets its material toward some of these different stakeholders. The overarching goal of the Division 53 website is to describe therapy models that have demonstrated effectiveness with youth. Consistent with the example above, many of the therapy models described on the website presumably target children and adolescents as the primary consumers of the treatment. However, the website does not contain information for youth, but rather has an entire section devoted to “parents, caregivers, and the public.” This section explicitly acknowledges that parents and caregivers are most likely to be the customers of treatment, who try to “find the most effective and efficient treatment for their child.” The website also has pages for professionals that contain more technical information about EBP models. The term “professional” is not clearly defined on the website, but could presumably include both intermediaries (clinicians who deliver EBP) and influencers (primary care doctors and other professionals who might recommend EBP to their patients).

Preparing for Marketing: The Marketing Mix

Once the rationale for DTC marketing has been established and the key players have been identified, another critical step is to consider all of the elements of the Marketing Mix. The Marketing Mix is one of the most commonly used planning frameworks in the field of marketing and is widely referred to as the 4 Ps: People, Product, Place, and Price. As noted by Zeithaml and colleagues (2012) in their best-selling marketing textbook:

These elements appear as core decision variables in virtually any marketing text or marketing plan. The notion of a mix implies that all the variables are interrelated and depend on each other to some extent. Further, the marketing mix philosophy implies an optimal mix of the four factors for a given market segment at a given point in time. (page 25).

In the following sections, each of the 4 Ps is defined and its applicability to the marketing of EBP for M/SU treatment is briefly discussed. Throughout the following sections, the aforementioned example of Division 53 of the APA, as an organization that seeks to promote the use of EBP models for youth, is used to provide a consistent illustration. Table 1 displays two sets of example questions for each of the 4 Ps. The first set contains questions that a treatment developer or organization seeking to market EBP should attempt to answer as part of the preparation process. The second set contains example questions that could be asked of the target customer during market research.

Table 1.

Example Preparation Questions for Each Element of the Marketing Mix

| Element | Questions for the Treatment Developer | Questions for the Target Customer |

|---|---|---|

| Product |

|

|

| Price |

|

|

| Place |

|

|

| Promotion |

|

|

Product

Defining the product – or in the case of M/SU treatment, the service – is an essential component of the marketing mix. A critical decision for our field and for organizations such as Division 53 is whether to market psychological interventions broadly (based on the view that any treatment is better than no treatment) or whether to only market those interventions with a certain level of empirical support (based on the view that we should only promote those treatments that have been shown to be effective). If our field chooses the latter approach, then another important decision point is which of the following to market: EBP as a general movement, broad categories of treatment (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based approaches, family therapy), or specific interventions (e.g, multisystemic therapy).

Considering the high level of unmet need for M/SU treatment in the United States (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013a), it seems unlikely that potential customers would have much existing knowledge or awareness of different treatment models; hence, there would likely be value to more basic, broad marketing efforts about psychological treatment or EBP in general. Of note, DTC marketing approaches in the pharmaceutical field have shown that marketing efforts for a specific product increase demand for the entire class of products; for instance, marketing dollars invested in Prozac have been found to increase demand for antidepressants in general (Donohue, Cevasco, & Rosenthal, 2007; Rosenthal, Berndt, Donohue, Epstein, & Frank, 2003). In the pharmaceutical field, this “rising tide raises all boat” phenomenon is arguably not that concerning, since all pharmaceutical products on the market have presumably undergone stringent clinical testing and have demonstrated effectiveness. By contrast, in the M/SU field, it is possible that DTC marketing for any model of therapy has the potential to increase demand for M/SU therapeutic interventions more broadly, regardless of therapy quality. This may not be of concern if the goal of the initiative is simply to increase the utilization of therapy, but it suggests that specific efforts to market EBP could backfire without sufficient attention to customer education. Thus, it is of paramount importance that DTC marketing initiatives for EBP include education about the following issues: definition of EBP; instructions as to how to find an EBP provider; and specific criteria to help customers ensure that they are actually receiving EBP. The Division 53 website attempts to address these issues through a section of the site titled, “What is Evidence-Based Practice?,” which contains information about how research support is defined and how to select a therapy provider.

In addition to defining and educating customers about the specific service, it is important to consider at least two other issues: 1) features of the service that the customer most values, and 2) how well the service address the features valued by the customer relative to other competitive options. Currently, the Division 53 page titled “What is Evidence-Based Practice?” appears to emphasize research support as the competitive advantage of EBP, through repeated comments about how EBP has a strong backing in scientific evidence. This approach presumes that parents searching for M/SU treatment value research evidence, an assumption that could be tested through qualitative market research. If Division 53 conducted market research and found that parents value different aspects of M/SU treatment, then a different approach would be prudent. For instance, suppose that Division 53 learned that parents most value therapy that improves their child’s M/SU symptoms and/or functioning. In this situation, the description of EBP on the “What is Evidence-Based Practice?” page could logically emphasize ways that EBP has been shown to reduce symptoms and impairment more effectively than other therapy options. By contrast, if market research indicated that parents most value a comfortable relationship between their child and their therapist, then the content of the marketing on the EBP webpage could focus more on the therapeutic process (the aspect most valued by the customer) than on the outcome. The aspects most valued by the customer would also inform decisions about the target competitor – in the second scenario, it might make more sense to compare EBP to medication (which doesn’t promote a relationship) than to compare EBP to another therapy model.

Price

Price is another key component of the marketing mix and pertains to both the price paid by the client and the messages the client receives about price. For M/SU treatment, the price paid by the patient includes both the direct financial cost of therapy sessions as well as barriers that reduce the likelihood of seeking treatment. Barriers to seeking service may be either external (e.g., environmental barriers) or internal (e.g., beliefs, knowledge, attitudes) (e.g., Xu, Rapp, Wang, & Carlson, 2008). Because the financial price of EBP is often set by insurance carriers and other third party payers, a treatment developer or intermediary may have limited control over the financial burden unless the provider or agency uses a private-pay model. In contrast, treatment developers or intermediaries have relatively more influence over internal and external barriers to service. As an example, treatment models that increase the ease of attendance through technology (e.g., computer-assisted therapy), co-located services at locations frequented by patients (e.g., schools, primary care offices), or services delivered in the patient’s home are likely to be viewed as less costly than office-based programs. Similarly, programs that help patients with logistical arrangements such as transportation and childcare may also be viewed as less costly. On the other hand, removing these logistical barriers may be associated with increased costs for the provider, which could reduce the feasibility of the service in the longer-term. Treatment developers and intermediaries must therefore attempt to analyze both the short-term and long-term effects of attempting to remove barriers to service.

It should also be noted that having the lowest price and least barriers to service is not necessarily the best marketing strategy. While there are some data that reducing barriers is effective in promoting treatment attendance, there are fewer data indicating that these efforts are associated with improved treatment outcome (e.g., Copeland, Hall, Didcott, & Biggs, 1993). An alternate approach to cutting price or reducing barriers is to focus on increasing the quality of treatment with the hope that patients or third party payers will pay more for higher quality. Reflecting this approach, some psychiatric hospitals and institutes have adopted tiered pricing strategies in which they offer an array of treatment options, ranging from programs that are wholly covered by insurance to premium programs that are private-pay (Robart, 2014). Furthermore, the notion of financially rewarding providers for higher quality treatment has been proposed as a key element of health care reform (New York Times Editorial Board, 2013). Indeed, one lever for EBP treatment developers and organizations such as Division 53 is to negotiate more directly with third party payers to try and develop tighter linkages between treatment quality and price. Efforts to negotiate with third party payers could target a number of barriers related to price including: ensuring that insurance approval covers the number of sessions required for the EBP protocol and ensuring that reimbursement for EBP is sufficient to keep EBP providers in network.

Finally, it is important to consider that marketing messages about price may be much more flexible than the actual price of the service. For instance, Division 53 could decide not to get involved with setting the cost of specific services, but could still take an active role in educating parents about the cost of service. Again, market research could help to develop the most compelling messages. If market research revealed that parents are most sensitive to the overall out-of-pocket cost of service, then marketing messages could emphasize the cost-effectiveness of EBP relative to other treatment options. These messages could also highlight the non-financial costs of other treatment models such as the potential side effects of medication or the risk of engaging in untested therapy. Alternately, if market research demonstrated that parents most care about whether their treatment is covered by insurance, then Division 53 could incorporate information about insurance coverage in the website’s “Find a Therapist” tool.

Place

Place refers to the channels through which both the actual service and information about the service are accessed by customers. At a basic level, decisions about place involve considerations about where to deliver the actual service. Reflecting a move toward greater integration of care, M/SU treatments are now increasingly distributed through a range of allied venues, including: primary care offices, schools or educational programs, emergency departments, urgent care clinics, and patients’ homes. Additionally, the advent of technology-assisted interventions is expanding the scope of places where therapeutic services can be accessed beyond traditional treatment settings (Kazdin & Blase, 2011). Not surprisingly, decisions about where to distribute the service are closely linked to the perceived price of the service, as well as the cost of service delivery.

Decisions about place also pertain to the distribution of information and require a solid understanding of the channels or locations through which the customer is most likely to seek out information. Due to the unique characteristics of services (e.g., services are not tangible, vary over time and across people, depend on an interaction with the customer, and cannot be returned), customers have a harder time evaluating the quality of services than the quality of products (Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, 1985). As a result, word-of-mouth communication about services is often considered more credible than other forms of marketing (Zeithaml et al., 2012, p 477). This is especially true for services that are high in “experience qualities” (where the customer must experience the service to determine quality) and “credence qualities” (where the customer may not be able to determine quality even after service delivery). By definition, therapy is high in both of these areas – it must be actively experienced by the customer and it may be hard for the customer to evaluate – suggesting that word-of-mouth referrals are likely to be one of the most critical sources of information when selecting a therapy provider.

Due to the significance of word-of-mouth referrals, decisions about where to place marketing materials should take into account the key influencers who are most likely to shape the customer’s behavior. This information can again be obtained through market research. For instance, Division 53 currently uses a website to promote information about EBP. The question then becomes: how do we increase the likelihood that customers will visit the website? If Division 53 conducted market research and learned that parents of youth with M/SU problems frequently look to their pediatricians and school counselors for treatment recommendations, then the marketing strategy could benefit from educating and partnering with these key influencers. Example outreach strategies to these influencers could include: asking them to routinely refer parents to the website, placing pamphlets about the website in their waiting rooms and offices, and distributing additional educational materials about EBP (as a companion to the website) to their offices. In a similar vein, if market research indicated that many parents of youth with M/SU problems ask their insurance company for a list of providers, then Division 53 could conduct targeted outreach to insurance companies in order to encourage referrals to those providers who offer EBP. Finally, Division 53 could conduct market research to learn which websites parents are most likely to visit first when researching M/SU treatment options, and could attempt to strategically advertise and/or place links on those websites.

Promotion

The final part of the Marketing Mix is perhaps the most well known and most commonly considered when discussing DTC marketing. Promotion refers to the process of proactively communicating with customers about the service. The goal of promotion activities is to deliver relevant content, through relevant channels, at an opportune time; or, put simply, to reach the target customer with the right message, at the right time, through the right means.

Promotion decisions rely heavily on the information gathered for other aspects of the Marketing Mix. For example, information gathered about which service attributes (Product) and information channels (Place) are most valued by customers should be reflected in a marketing campaign’s key messages and distribution strategies, respectively. Feedback from the customer and key influencers will also inform decisions about the opportune time to distribute promotional materials. Continuing the example of Division 53, if the organization decided to partner with pediatricians and learned that pediatricians have a “rush” of physicals at the end of the summer, then it would be prudent to place promotional materials about M/SU treatment in pediatrician offices before this rush. By contrast, if Division 53 partnered with insurance companies and learned that these companies receive very few requests for M/SU referrals over the summer, then it would be illogical to target promotional efforts toward these companies during the summer.

Another consideration when developing a promotion strategy is to ensure that the promotional materials effectively differentiate the service being marketed from alternate options. To return to the example of psychiatric medication, the most effective advertisements are those that clearly distinguish a specific medication from other similar medications. As an example, the original commercial for Zoloft had the slogan, “the number one prescribed drug of its kind.” Although this slogan does not specify why Zoloft is preferred, it clearly communicates that the medication is prescribed (and therefore trusted) more by doctors than other options on the market. Advertisements for the sleep medication Ambien were even more specific about the drug’s relative advantages. The early commercials for Ambien described the medication’s 2-layer system, with the statement, “Unlike other sleep aids, a second [layer] dissolves slowly to help you stay asleep.” Statements such as these that communicate a service’s unique competitive advantage are often referred to as “positioning statements” and represent one of the most important aspects of a compelling Marketing Mix (Stayman, 2013).

Finally, it is of paramount importance that positioning statements and associated promotional materials use language that is easily comprehensible to the target customer. In (2009), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a guide called Simply Put to help researchers transform scientific and complicated information into health messages that are clear, relevant, and meaningful to the target customer. As noted in this CDC guidance, it is important that health messages are communicated very simply, considering that about one-third of the United States population has difficulty reading and acting upon health information (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Ideally, the clarity of promotional messages can be evaluated through market research. For instance, the Division 53 website currently has the tagline “Evidence-Based Mental Health Treatment for Children and Adolescents.” There is reason to believe that this description might be hard for website visitors to understand. In a survey and qualitative research with over 1,500 healthcare consumers (defined as adults with health insurance), Carman and colleagues (2010) found that many individuals are confused by the concept of “evidence-based” health care and had negative impressions of what it might mean. The Division 53 website has an entire page devoted to defining EBP, but the page introduces some complex terms and concepts such as, “psychotherapy,” “scientific evidence,” “random assignment,” and a five-level system to evaluate the quality of research support (see Southam-Gerow & Prinstein, 2013). While the information on this page might be technically accurate, the level of sophistication might be beyond that of distressed parents searching for information about their children’s treatment. The goal of promotional messages is to provide information that balances accuracy with simplicity. Thus, a valuable question for future market research with potential customers of M/SU treatment is how to convey the concept of “evidence-based mental health treatment” using language that is understandable, accurate, and appealing.

Additional Ps

When the goal of marketing is to influence social behaviors for the benefit of the target customer and the general society, instead of for the direct benefit of the marketer, then the approach is described as “social marketing.” Weinreich (2010) has argued that the planning phase in social marketing should be augmented with 4 additional Ps: pubic, partnership, policy, and purse strings. These Ps are briefly discussed in the following paragraphs.

The Public and Partnership components serve as reminders that there are often many audiences or stakeholders that need to be involved in approving, implementing, or supporting social marketing campaigns. The Public that is targeted by a campaign may extend beyond the key stakeholders defined earlier (e.g., customers, intermediaries, influencers), to an array of individuals who influence the feasibility of the marketing strategy such as funding institutes, policy makers, regulatory boards, and insurance agencies. Once the myriad of potential Public audiences has been identified, it is valuable to consider whether formal Partnerships should be established. Social and health issues are often so complex that one group or organization cannot effectively address them without the support of formal collaborators and partnerships. Division 53, for instance, partnered with the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies for sponsorship of its website, and the website’s home page identifies another six partner sites that support similar missions.

The final two components – Policy and Purse strings – highlight the need to collaborate with policy makers and funding institutes in order to support direct-to-consumer marketing efforts. The Purse strings component reflects the need to think creatively about how to fund social marketing campaigns. Because treatment developers are rarely compensated for disseminating EBP, marketing efforts often need to be funded by alternate sources such government grants, foundations, membership dues, or private donations. Division 53’s website, as an example, is likely funded through a combination of membership dues and the service contributions (typically unpaid) of researchers on the leadership team. This raises a key question: how will these initiatives be sustained in the longer-term? Reflecting this challenge, the Policy component highlights the fact that long-term maintenance of social marketing may require policy change. Therefore, a comprehensive marketing strategy intended to increase the utilization of EBP might include a lobbying component that educates policy makers about the benefits of EBP. The goal of such lobbying might be to promote systemic incentives for community clinicians and agencies delivering EPB such as differential reimbursement rates.

Summary

In conclusion, the current review has highlighted the fact that the existing “quality chasm” consists of two inter-related gaps: a research-to-practice gap and a treatment gap. Traditional D&I efforts have predominantly focused on the research-to-practice gap by focusing on the relationship between treatment developers and providers. As such, these efforts can be conceptualized as using a “push approach” to improve the quality of treatment in the community. DTC marketing that directly targets patients and caregivers represents a complementary strategy that can serve to broaden the scope of these efforts by using a “pull approach” to increase customer awareness of and demand for quality treatment. DTC marketing should not be viewed as a replacement to traditional D&I efforts, but rather as an important part of the overall D&I puzzle. Efforts to address the research-to-practice gap are likely to be less influential if customers do not demand the services provided, while efforts to address the treatment gap are likely to be less influential if customers who demand EBP cannot find it in their community. Our field’s efforts have the potential to be most effective when we pursue both push and pull approaches simultaneously in an integrated fashion (see Kibilko, 2013).

The use of DTC marketing strategies requires a substantial commitment to preparation, which involves a careful consideration of the key stakeholders involved as well as the core elements of the Marketing Mix. The example of Division 53 of the American Psychological Association was used throughout the second half of this manuscript to illustrate some of the key considerations involved with using the Marketing Mix to prepare for DTC marketing. It is also important to note that the concepts discussed in this manuscript have been well established in the field of marketing, but their relevance to the dissemination of EBP has been virtually unstudied. Research to empirically evaluate the relevance and effectiveness of the different marketing strategies discussed in this review is essential to help inform future efforts.

Over 10 years ago, the IOM put forth the mandate to bridge the quality chasm by taking into account both scientific findings and patient preferences. Our efforts thus far have made slow progress on this front, primarily through a focus on getting scientific findings into practice. Listening to customers’ preferences for information, and designing our marketing efforts accordingly, represents an emerging way to expand the scope of existing D&I efforts. Ultimately, the use of complementary approaches that engage both practitioners and customers will hopefully enable us to meet our goal of increasing the utilization of quality M/SU treatment.

Acknowledgments

The conceptualization and writing of this manuscript was supported by NIDA grant K23DA031743 awarded to Sara J. Becker. The author is extremely grateful to her team of mentors for helping her to develop the ideas and research approach described in this manuscript: Anthony Spirito, Ph.D. (Co-Primary Mentor), Valarie Zeithaml, DBA (Co-Primary Mentor), Daniel Squires, Ph.D. (Co-Mentor) and Melissa Clark, Ph.D. (Co-Mentor).

References

- Aarons GA. Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The evidence-based practice attitude scale (EBPAS) Mental Health Services Research. 2004;6(2):61–74. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000024351.12294.65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:MHSR.0000024351.12294.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addis ME, Wade WA, Hatgis C. Barriers to dissemination of evidence-based practices: Addressing practitioners' concerns about manual-based psychotherapies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6(4):430–441. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.6.4.430. [Google Scholar]

- Amaya-Jackson L, Ebert L, Forrester A, Deblinger E. Fidelity to the learning collaborative model: Essential elements of a methodology for the adoption and implementation of evidence-based practices; Paper presented at the National Child Traumatic Stress Network; Anaheim, CA. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17(1):1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA. Getting research findings into practice: Closing the gap between research and practice: An overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. British Medical Journal. 1998;317(7156):465. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan R. Examples of firms using a push strategy. The Houston Chronicle, Small Business by Demand Media. 2014 Retrieved from: http://smallbusiness.chron.com/examples-firms-using-push-strategy-14033.html. [Google Scholar]

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud P-AC, Rubin HR. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(15):1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman KL, Maurer M, Yegian JM, Dardess P, McGee J, Evers M, Marlo KO. Evidence That Consumers Are Skeptical About Evidence-Based Health Care. Health Affairs. 2010;29(7):1400–1406. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0296. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Simply Put: A Guide for Creating Easy to Understand Materials. Third Edition. Atlanta, Georgia: 2009. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/toolstemplates/simply_put_082010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Condon TP, Miner LL, Balmer CW, Pintello D. Blending addiction research and practice: Strategies for technology transfer. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35(2):156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.09.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J, Hall W, Didcott P, Biggs V. A comparison of a specialist women's alcohol and other drug treatment service with two traditional mixed-sex services: Client characteristics and treatment outcome. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1993;32(1):81–92. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90025-l. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0376-8716(93)90025-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Steiner L, McCracken SG, Blaser B, Barr M. Strategies for disseminating evidence-based practices to staff who treat people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(12):1598–1606. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1598. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven M, Bland R. Better practices in collaborative mental health care: An analysis of the effective base. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, Morosini P. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(21):2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennehy EB, Bauer MS, Perlis RH, Kogan JN, Sachs GS. Concordance with treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder: Data from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder. Psychopharmacology Bull. 2007;40(3):72–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, Donaldson J, Webb C. The cannabis youth treatment study (CYT): Main findings from two randomized trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27(3):197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue JM, Cevasco M, Rosenthal MB. A decade of direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(7):673–681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa070502. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa070502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling GR. The art and science of marketing: Marketing for marketing managers. Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Bond GR, Essock SM. Implementing evidence-based practices for people with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2009;35(4):704–713. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp041. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Goldman HH, Leff HS, Lehman AF, Dixon L, Mueser KT, Torrey WC. Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(2):179–182. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewan CE, Whaite A. Training health professionals in substance abuse: A review. Substance Use & Misuse. 1982;17(7):1211–1229. doi: 10.3109/10826088209056350. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10826088209056350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin DA, Reid MC, O'Connor PG. Screening for alcohol problems in primary care: A systematic review. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(13):1977. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.1977. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.13.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo KP, Comer JS, Barlow DH. Direct-to-consumer marketing of psychological treatments for anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27(8):793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, Ustun T, Piccinelli M, Gureje O, Rutter C. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27(01):191–197. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004242. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291796004242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes B, Haines A. Getting research findings into practice: Barriers and bridges to evidence based clinical practice. British Medical Journal. 1998;317(7153):273. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7153.273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7153.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions. Natl Academy Pr.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among US children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Blase SL. Rebooting psychotherapy research and practice to reduce the burden of mental illness. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6(1):21–37. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393527. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1745691610393527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Holland L, Crowley M. Family experience of barriers to treatment and premature termination from child therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(3):453–463. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.453. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.65.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibilko J. How can retailers use push & pull advertising? [Retrieved on April 22, 2014];Small Business by Demand Media. 2013 from: http://smallbusiness.chron.com/can-retailers-use-push-pull-advertising-17743.html. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82(11):858–866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb CW, Hair JF, Jr, McDaniel CD. Essentials of marketing. Sixth Edition. South-Western Cengage Learning; 2010. p. 413. [Google Scholar]

- Lang ES, Wyer PC, Haynes RB. Knowledge translation: closing the evidence-to-practice gap. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2007;49(3):355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.08.022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride D, Voss W, Mertz H, Villaneuva T, Smith G. Mental health evidence-based practices (EBPs) in Washington state: The 2007 evidence-based practices (EBP) survey. Tacoma, WA: Washington Institute for Mental Health Research Training; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McGovern MP, Fox TS, Xie H, Drake RE. A survey of clinical practices and readiness to adopt evidence-based practices: Dissemination research in an addiction treatment system. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;26(4):305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Barlow DH. The dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychological treatments: A review of current efforts. American Psychologist. 2010;65(2):73. doi: 10.1037/a0018121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sorensen JL, Selzer JA, Brigham GS. Disseminating evidence-based practices in substance abuse treatment: A review with suggestions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31(1):25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(6):1050. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney-Day N, DeAngelo D, Chen C-n, Cook BL, Alegría M. Unmet need for treatment for substance use disorders across race and ethnicity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;125:S44–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York Times Editorial Board. Report Card on Health Care Reform. The New York Times. 2013:SR12. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/24/opinion/sunday/report-card-on-health-care-reform.html?_r=0. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Ferriter C. Parent management of attendance and adherence in child and adolescent therapy: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2005;8(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-4753-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10567-005-4753-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagoto SL, Spring B, Coups EJ, Mulvaney S, Coutu MF, Ozakinci G. Barriers and facilitators of evidence-based practice perceived by behavioral science health professionals. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;63(7):695–705. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. The Journal of Marketing. 1985:41–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1251430. [Google Scholar]

- Porter DM. Direct-to-consumer (DTC) pharmaceutical marketing: Impacts and policy implications. School of Public, Nonprofit and Health Administration Review. 2011;7(1):5. [Google Scholar]

- Robart M. Residential Treatment Services: McLean Hospital. Belmont, MA: McLean Hospital; 2014. Retrieved from: http://mclean.harvard.edu/pdf/patient/adult/mclean-residential-service-1210.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal MB, Berndt ER, Donohue JM, Epstein AM, Frank RG. Demand effects of recent changes in prescription drug promotion. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton JL, Fant KE, Clark SJ. Use of practice guidelines in the primary care of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):e23–e28. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.114.1.e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Dwight-Johnson M, Klap R. Psychological distress, unmet need, and barriers to mental health care for women. Women's Health Issues. 2001;11(3):231–243. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(01)00086-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1049-3867(01)00086-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sholomskas DE, Syracuse-Siewert G, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA, Nuro KF, Carroll KM. We don't train in vain: A dissemination trial of three strategies of training clinicians in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):106. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolders M, Laurant M, Verhaak P, Prins M, van Marwijk H, Penninx B, Grol R. Adherence to evidence-based guidelines for depression and anxiety disorders is associated with recording of the diagnosis. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31(5):460–469. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.05.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Prinstein MJ. Evidence base updates: The evolution of the evaluation of psychological treatments for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;43(1):1–6. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.855128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.855128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stayman D. How to write market positioning statements. The Marketing Blog: eCornell. 2013 Retrieved from: http://themarketingblog.ecornell.com/how-to-write-market-positioning-statements/ [Google Scholar]

- Stirman SW, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: A review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implementation Science. 2012;7:17. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Office of Applied Studies, NHSDA Series H-22, DHHS Publication No. SMA 03–3836. Rockville, MD: 2003. Results from the 2002 national survey on drug use and health: National findings. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No.(SMA) Rockville, MD: 2013a. Results from the 2012 national survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings; pp. 13–4795. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Systems-level implementation of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Technical Assistance Publication (TAP) Series 33. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 2013b:13–4741. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski J. Using direct-to-consumer marketing strategies with obsessive-compulsive disorder in the nonprofit sector. Behavior Therapy. 2012;43(2):251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.05.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: Models for dissemination and implementation research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43(3):337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai B, Straus MM, Liu D, Sparenborg S, Jackson R, McCarty D. The first decade of the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network: Bridging the gap between research and practice to improve drug abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;38:S4–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.01.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventola CL. Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising: Therapeutic or toxic? Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2011;36(10):669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virani T, Lemieux-Charles L, Davis DA, Berta W. Sustaining change: Once evidence-based practices are transferred, what then? Healthcare Quarterly. 2008;12(1):89–96. 82. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2009.20420. http://dx.doi.org/10.12927/hcq.2009.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich NK. Hands-on social marketing: a step-by-step guide to designing change for good. 2nd ed. Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weist MD, Rubin M, Moore E, Adelsheim S, Wrobel G. Mental health screening in schools. Journal of School Health. 2007;77(2):53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00167.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells EA, Saxon AJ, Calsyn DA, Jackson TR, Donovan DM. Study results from the Clinical Trials Network's first 10 years: Where do they lead? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;38:S14–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.12.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C. Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):2027–2032. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Rapp RC, Wang J, Carlson RG. The multidimensional structure of external barriers to substance abuse treatment and its invariance across gender, ethnicity, and age. Substance Abuse. 2008;29(1):43–54. doi: 10.1300/J465v29n01_06. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J465v29n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml V, Bitner MJ, Gremler D. Services marketing: integrating customer focus across the firm. 6th ed. McGraw-Hill Higher Education; 2012. [Google Scholar]