Abstract

We designed and pilot-tested a group-based, work-related cognitive-behavioral therapy (WCBT) for unemployed individuals with social anxiety disorder (SAD). WCBT, delivered in a vocational service setting by vocational service professionals, aims to reduce social anxiety and enable individuals to seek, obtain, and retain employment. We compared WCBT to a vocational services as usual control condition (VSAU). Participants were unemployed, homeless, largely African American, vocational service-seeking adults with SAD (N=58), randomized to receive either eight sessions of WCBT plus VSAU or VSAU alone and followed three months post-treatment. Multilevel modeling revealed significantly greater reductions in social anxiety, general anxiety, depression, and functional impairment for WCBT compared to VSAU. Coefficients for job search activity and self-efficacy indicated greater increases for WCBT. Hours worked per week in the follow-up period did not differ between the groups, but small sample size and challenges associated with measuring work hours may have contributed to this finding. Overall, the results of this study suggest that unemployed persons with SAD can be effectively treated with specialized work-related CBT administered by vocational service professionals. Future testing of WCBT with a larger sample, a longer follow-up period, and adequate power to assess employment outcomes is warranted.

Keywords: Social Anxiety, CBT, Employment, Group, Underserved Populations

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) has been linked to deficits in occupational functioning (Bruch, Fallon, & Heimberg, 2003). Over 90% of people with SAD report significant impairment in one or more areas of occupational functioning (Turner, Beidel, Dancu, & Keys, 1986) including turning down job offers or promotions (Stein & Kean, 2000), reduced work performance and productivity, and high rates of absenteeism (Wittchen, Fuetsch, Sonntag, Muller, & Liebowitz, 2000). Occupational success in individuals with SAD is also limited by their lowered educational achievement (Stein & Kean, 2000). Two recent longitudinal studies provide further support for the significant relationship between social anxiety and protracted unemployment (Moitra, Weisberg, Keller, & Martin, 2011; Tolman et al., 2009).

We postulate that SAD interferes with job attainment and retention for several reasons including but not limited to: reduced job qualifications related to less education and training; job interview-related anxiety and avoidance; limited social networks to provide job leads; and problems retaining work due to limited social connections with co-workers. It is also likely that lowered self-esteem and embarrassment related to unemployment often increase social evaluative concerns, which likely results in a negative feedback loop that further strengthens the relationship between social anxiety and unemployment.

The main evidence-based psychosocial treatment for SAD is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). The efficacy of CBT for SAD has been well documented in meta-analytic reports and it can be delivered in both group and individual formats with similar outcomes (Acarturk, Cuijpers, van Straten, & de Graaf, 2009). Of particular relevance to the current investigation is that while the primary benefits of CBT for SAD involve reductions in social anxiety symptoms, occupational and other functional targets are often left in need of further improvement (Blanco et al., 2010). Further, many individuals with SAD do not receive CBT (Wang et al., 2005). Treatment utilization is even lower among minorities (Neighbors et al., 2007) and the poor (Alegria, Bijl, Lin, Walters, & Kessler, 2000).

One potential method of improving access to CBT is to offer it in non-mental health venues that are less stigmatizing and often more accessible than traditional mental health centers. Relevant to the present investigation, vocational service centers offer a promising site to treat individuals whose job attainment have been compromised by SAD. CBT targeting both mental health symptoms and employment problems has been successfully implemented in vocational rehabilitation settings (Brewin, Collins, & Papageorgis, 2011; Della-Posta & Drummond, 2006; Vinokur, Schul, Vuori, & Price, 2000). Among the most thoroughly evaluated of these programs is the Winning New Jobs Program (JOBS; Vinokur et al., 2000) a short-term, group intervention designed to improve job acquisition and retention and prevent the development of depression among recently unemployed workers. The JOBS program has significantly improved employment outcomes and prevented depression among participants (Vinokur et al., 2000). It is important to note that the JOBS program and most other similar programs focus on prevention of mental health problems and/or reducing symptoms (Vinokur et al., 2000) in comparison to the very few programs that target job-seekers with diagnosed mental disorders (Lagerveld & Blonk, 2012). Finally, no existing programs targeting mental health barriers to employment focus on SAD or are delivered exclusively by vocational service professionals.

This project involves pilot-testing of a group-based, work-related cognitive-behavioral therapy (WCBT) for unemployed individuals with SAD. WCBT is informed by the JOBS intervention and is designed for delivery in a vocational service setting by vocational services professionals. In the present investigation, mostly minority, homeless, impoverished job-seekers with SAD were randomly assigned to either standard vocational services accompanied by WCBT or to a vocational service as usual (VSAU) control condition. We predicted that participants assigned to the WCBT(+VSAU) group would experience reduced social anxiety and improved employment-related outcomes compared to VSAU alone.

Method

Design

Fifty-eight participants with SAD were randomized to either WCBT or VSAU at a vocational rehabilitation center (Jewish Vocational Services Detroit – JVSD). WCBT sessions were provided concurrently with vocational services but were scheduled during the business day when standard vocational services were not offered. Participant enrollment took place between May, 2010, and December, 2011. Participants completed structured diagnostic interviews and assessments at baseline (BL), immediately post-treatment (PT), and 3-months post-treatment (FU). Final follow-up interviews were completed in March, 2012. Assessment personnel were blinded to participants’ treatment condition. As required by the human subjects committee, the consent document informed participants that they could be assigned to one of two conditions, usual services or usual services plus CBT sessions.

Participants

Participants were unemployed, vocational service-seeking adults with SAD. Human subjects approval was granted through the Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained, and all participants received $40 for each assessment; WCBT participants also received $10 for each group session attended to offset transportation costs and as an incentive to complete weekly symptom and WCBT adherence ratings. Participants were excluded if they met criteria for current substance dependence, used opiates or freebase cocaine, had active psychotic or manic symptoms deemed to interfere with group participation, or reported suicidal/homicidal ideation with imminent risk.

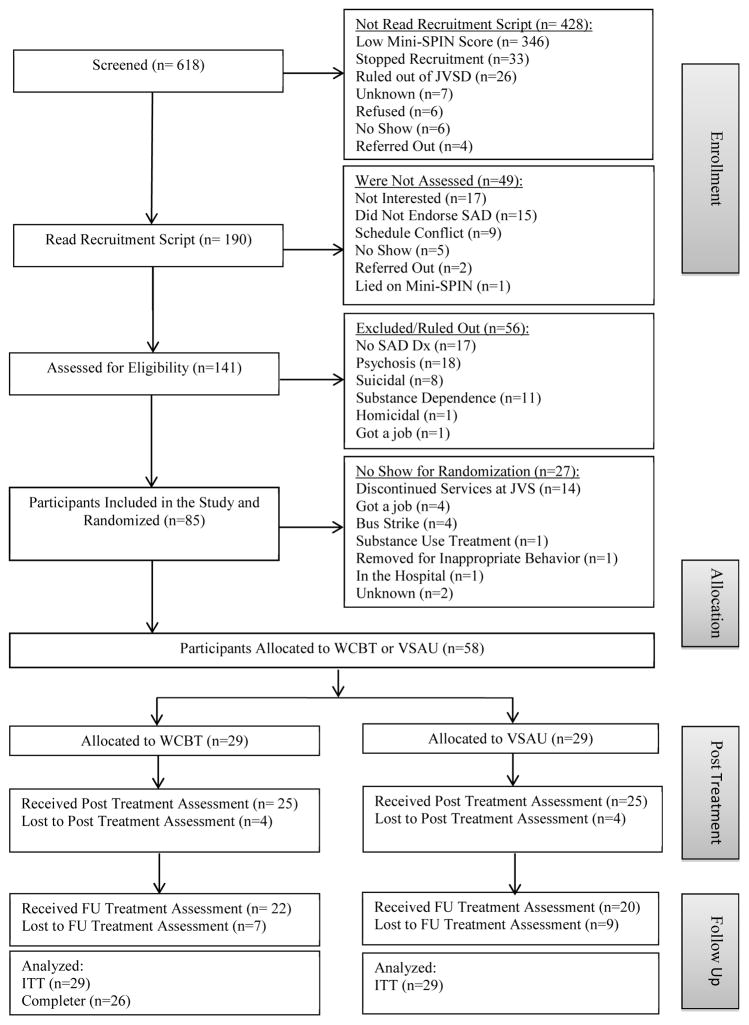

Eligible participants were recruited and assembled into cohorts of approximately 6 individuals. Once a cohort was assembled, cohort members were directed to meet together at JVSD to learn if they were randomized to WCBT or VSAU alone. Of the 85 eligible individuals recruited into cohorts, 58 (68.2%) attended the randomization meeting and were randomized to condition using opaque sealed envelopes drawn by a research associate noting either WCBT or VSAU. For cohorts randomized to WCBT, the first session immediately followed the randomization meeting. Reasons for failing to attend the randomization meeting are summarized in Figure 1. Individuals who did not attend the randomization meeting did not significantly differ from those who did attend on any demographic or clinical characteristic. The number of individuals in each cohort who attended the randomization meeting ranged from 2 to 7 (M = 4.14, SD = 2.39) and did not differ by condition. Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of the 58 successfully randomized participants.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through study phases.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by condition

| WCBT a(n=29) | VSAU b(n=29) | Total (N=58) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | |

| Race | ||||||

| African American | 27 | 93.10% | 23 | 79.30% | 50 | 86.20% |

| White | 2 | 6.90% | 4 | 13.79% | 6 | 10.34% |

| Multiracial | 0 | 0% | 2 | 6.90% | 2 | 3.45% |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 20 | 69.00% | 19 | 65.50% | 39 | 67.20% |

| Women | 9 | 31.00% | 10 | 34.50% | 19 | 32.80% |

| Education | ||||||

| 8 years or less | 3 | 10.30% | 1 | 3.40% | 4 | 6.90% |

| 9–11 years | 10 | 34.50% | 9 | 31.00% | 19 | 32.80% |

| High School Graduate | 9 | 31.00% | 12 | 41.40% | 21 | 36.20% |

| 13–16 years | 6 | 20.70% | 5 | 17.20% | 11 | 19.00% |

| College Graduate | 1 | 3.40% | 2 | 6.90% | 3 | 5.20% |

| Age | ||||||

| 19–30 | 0 | 0.00% | 4 | 13.80% | 4 | 6.90% |

| 31–40 | 6 | 2.07% | 7 | 24.10% | 13 | 22.40% |

| 41–50 | 18 | 62.10% | 12 | 41.40% | 30 | 51.70% |

| 51–60 | 5 | 17.20% | 6 | 20.70% | 11 | 18.90% |

| Mean Age | 44.93 | 42.24 | 43.59 | |||

| SD | 6.19 | 10.21 | 8.48 | |||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married | 0 | 0% | 1 | 3.40% | 1 | 1.70% |

| Separated | 6 | 20.70% | 2 | 6.90% | 8 | 13.80% |

| Divorced | 6 | 20.70% | 7 | 24.10% | 13 | 22.40% |

| Widowed | 0 | 0% | 2 | 6.90% | 2 | 3.40% |

| Never Married | 17 | 58.60% | 17 | 58.60% | 34 | 58.60% |

| Employed any time in past year | 20 | 68.97% | 12 | 41.40% | 32 | 55.17% |

| Household income in past year | ||||||

| Less than $10,000 | 26 | 89.66% | 27 | 93.10% | 53 | 91.38% |

| $10,000 – $29,999 | 3 | 10.30% | 2 | 6.90% | 5 | 8.62% |

| Current Psychiatric Diagnoses | ||||||

| Depression | 18 | 62.10% | 17 | 58.60% | 35 | 60.30% |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 10 | 34.50% | 12 | 41.40% | 22 | 37.90% |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 7 | 24.10% | 4 | 13.80% | 11 | 19.00% |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 5 | 17.20% | 4 | 13.80% | 9 | 15.50% |

| Panic disorder | 5 | 17.20% | 3 | 10.30% | 8 | 13.80% |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 | 3.40% | 1 | 3.40% | 2 | 3.40% |

| Psychotic disorder | 1 | 3.40% | 1 | 3.40% | 2 | 3.40% |

| Specific phobia | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 3.40% | 1 | 1.70% |

| Substance abuse or dependence (lifetime) | 26 | 89.66% | 17 | 58.62% | 43 | 74.14% |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 21 | 72.40% | 17 | 58.60% | 38 | 65.52% |

| Cannabis abuse or dependence | 16 | 55.17% | 8 | 27.60% | 24 | 41.38% |

| Cocaine abuse or dependence | 16 | 55.17% | 7 | 24.10% | 23 | 39.66% |

| Sedative/hypnotic/anxiolytic abuse or dependence | 4 | 13.79% | 2 | 6.90% | 6 | 10.34% |

| Opioid abuse or dependence | 9 | 31.03% | 5 | 17.20% | 14 | 24.14% |

Work-related cognitive behavioral therapy;

Vocational services as usual

Treatment Conditions

Seven cohorts (n=29) received WCBT and seven cohorts (n=29) received VSAU. WCBT cohorts received eight, two-hour sessions held twice weekly over the course of four weeks in addition to standard vocational services. VSAU participants received standard vocational services which included, but were not limited to, career assessment, résumé construction, job interviewing skills, and job placement assistance. As a result of participating in the WCBT sessions, WCBT participants received up to 16 hours of additional professional contact compared to those assigned to VSAU.

Intervention

WCBT design efforts began with Heimberg and Becker’s (Heimberg & Becker, 2002) manualized group CBT for SAD. We also utilized the JOBS program manual (Vinokur et al., 2000) to inform our intervention. WCBT involves psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and exposure exercises. WCBT also includes limited social skills training related to the work environment.

Session 1 of WCBT involves psychoeducation related to SAD and its effect on employment. Session 2 primarily involves instruction in the identification of automatic thoughts. Session 3 involves further discussion about how SAD relates to the world of work and instructs participants in constructing rational responses to their automatic thoughts. Sessions 4 through 8 include a psychoeducational topic related to the world of work, in-session exposure as well as cognitive restructuring, and homework exercise planning (contact corresponding author for a full description of WCBT and the study protocol).

Therapists

Three vocational services employees served as WCBT group leaders. There were two leaders for each WCBT session. Two leaders completed approximately 50 hours and the third received 30 hours of training with specialists in CBT for anxiety disorders. Weekly supervision occurred throughout the project.

Assessments

Trained assessors had at least a master’s degree in a mental health-related field. Major outcomes were measured at baseline (BL), post-treatment (PT) and at follow-up (FU). All assessments were conducted at JVSD. PT assessments were conducted 4 weeks after randomization and FU assessments were conducted 12 weeks after PT for all participants.

Measures

Psychiatric Diagnoses

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-1 Disorders – Patient Edition (SCID-I/P; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995) was used to determine the presence of SAD and a range of other psychiatric disorders. The SCID was administered at BL, but only the social anxiety section of the SCID was administered at PT and FU. The SCID also provides a symptom severity rating for SAD which was administered at BL, PT and FU.

Measures of social anxiety

The primary measure in this realm was the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS; Liebowitz, 1987). The LSAS assesses fear and avoidance of social interaction and performance situations and was administered at BL, PT and FU. Scoring ranges from: moderate (55–65); marked (66–80); severe (81–95); to very severe (greater than 95). For the present study, we created ten additional questions, modeled after the LSAS that were specifically designed to measure fear and avoidance of work-related social situations. These questions yielded fear and avoidance sub-scores (current sample alpha = .81 to .90 and .79 to .87, respectively), in addition to a total score of work-related social anxiety (current sample alpha = .89 to .92).

The Mini Social Phobia Inventory (Mini-SPIN; Connor, Kobak, & Churchill, 2001) was administered as a screening instrument and as a measure of social anxiety symptoms at BL, PT and FU. Prior research on the Mini-SPIN indicates that nearly 90% of persons scoring 6 or more meet structured interview criteria for generalized SAD (Connor et al., 2001). In the present study, we utilized a cut-off score of 4 or greater as a screening threshold given that our research with this population indicates that a score of 4 maximizes sensitivity and specificity and produces a diagnostic accuracy rate of 83.4% (Levine et al., 2013).

The Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation scale (BFNE; Leary, 1983) was administered to WCBT participants weekly throughout treatment to monitor session-by-session changes in social anxiety.

The Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI) - Symptom Severity Rating (Guy, 1976), modified to rate the severity of SAD (Zaider, Heimberg, Fresco, Schneier, & Liebowitz, 2003) was used to assess the overall severity of participants’ social anxiety symptoms at BL, PT, and at FU. The CGI rates severity of illness within the last week using a seven-point categorical scale, ranging from 1 (normal, not at all) to 7 (among the most extremely ill patients).

Measures of other psychiatric symptoms

General anxiety was measured by the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1991), and depressive symptoms were measured via the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). Both questionnaires were administered at BL, PT and FU.

Measure of functioning

Overall disability was measured at BL, PT and FU using the Sheehan Disability Scale (Sheehan, Harnett-Sheehan, & Raj, 1996).

Measures of employment

Measures of work status and time to re-employment were collected at PT and FU using a modified version of a work activity questionnaire designed by Vinokur and colleagues (2000). This questionnaire also inquired about the number of job interviews and job applications completed during the follow-up period. Job search self-efficacy and motivation were measured at PT and FU using Vinokur et al.’s (2000) scales. These scales assessed job search self-efficacy (current sample alpha = .88 to .92) and job search activities (current sample alpha = .86 to .89). Average number of paid hours worked per week was assessed via participant self-report.

Measures of other treatment

The Morisky Adherence Measure (Morisky, 1986) was used to assess medication use throughout the trial. Finally, study-specific recording forms tracked the number and type of JVSD services utilized by participants.

Treatment Integrity

Trained independent evaluators with at least a master’s degree and experience in CBT, rated WCBT fidelity using a modified version of the Treatment Adherence Scale (TAS) for SAD which measures both protocol adherence and therapist competence (Hope, VanDyke, Heimberg, Turk, & Fresco, 1999). TAS modifications included specific reference to vocational content. TAS ratings range from 1 (ineffective) to 5 (extremely effective). A rating of 4 to 5 is considered within protocol.

Data Analysis

Appropriate to the cluster-randomized design and delivery of the intervention in groups, multilevel modeling (MLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) was used. Between-cohort variability was minimal for anxiety outcomes (intraclass correlation (ICC) < .01) but larger for depression (ICC = .07) and work hours (ICC = .05), indicating that a multilevel, mixed effects analytic approach was needed. Estimation used full information maximum likelihood (FIML), in HLM 7 (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2011). Three-level MLM accommodated 3 assessments over time (level 1) for each of the 58 individual participants (level 2), nested within the 14 cohorts (level 3) randomized to WCBT or VSAU. At level 1, time (days since baseline) was centered at the 3-month follow-up assessment, to provide an estimate of intervention effects at this final point. Models incorporated random estimates of intercepts and slopes to fit each participant’s pattern of scores over time. At level 2, models incorporated individuals’ baseline scores on the dependent variable as covariates. Condition (WCBT vs. VSAU) was entered at level 3, reflecting random assignment at the cohort level. Effect sizes (d) for condition effects on the cohort-average intercepts (3-month follow-up) and slopes were calculated as B divided by the intercept or slope SD, respectively, from a 3-level model containing only time and the baseline covariate (Raudenbush & Liu, 2001).

All analyses involved the complete sample of 58 individuals who attended the randomization meeting, including the 3 assigned to the WCBT condition who attended less than 2 treatment sessions. The original design planned for 60 individuals in 10 randomly assigned cohorts of 6, which would have provided statistical power of .8 to detect as significant at two-tailed p < .05 a large condition effect (d > 0.99), assuming a moderate intraclass correlation of .05 (Raudenbush & Liu, 2001). Because approximately one third of enrolled participants did not attend the initial meeting to learn of their cohort’s randomization, it was necessary to extend recruitment to 14 cohorts, resulting in 58 participants. With 14 cohorts, each with an average of 4 participants, power of the final design remained virtually identical: .8 to detect a slightly smaller condition effect (d ≥ 0.96).

Missing Data

PT interviews were conducted with 50 of the 58 participants (86.2%); 25 of 29 in both WCBT and VSAU. Three-month FU interviews were conducted with 42 participants (72.4%); 22 of 29 in WCBT and 20 of 29 in VSAU. Both PT and FU interviews were completed with 39 of the 58 participants (67.2%); 20 WCBT and 19 VSAU. One participant who dropped out of treatment was interviewed at FU; the other two could not be located. There were no significant condition differences in interview completion, and no differences between individuals who completed PT and FU interviews and those who were missing one or both. To avoid bias and optimize statistical power, all cases were included in outcome analysis, using expectation maximization methods appropriate for repeated measures data, estimating missing values from available data on all outcome, demographic and clinical assessment variables (Schafer & Graham, 2002). Missingness was assumed to be completely random (Little’s MCAR chi square = 166.76, p = 1.00). Pattern mixture modeling (Enders, 2010) detected no significant effects attributable to patterns of missingness and no effects of Missingness x Condition interactions.

Results

Participants

Randomization was successful in producing equivalent groups. The 58 participants randomly assigned to WCBT (n=29) and VSAU (n=29) did not differ significantly on Bonferroni-adjusted comparisons of baseline demographic or clinical characteristics or on continuous outcome variables measured at baseline. There were no condition differences on the amount or type of vocational services received at JVSD or the duration of engagement in the overall JVSD program. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants in each condition are reported in Table 1, and outcome variables across time and condition are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Outcome variables across time, by condition – Means and standard deviations (SD)

| Potential Score Range | Baseline | Post | Follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| LSASa -Total | 0–144 | WCBT | 84.31 | 31.51 | 66.72 | 29.02 | 65.31 | 37.44 |

| VSAU | 87.59 | 26.33 | 90.62 | 36.67 | 92.79 | 36.26 | ||

| LSASa- Anxiety Subscale | 0–72 | WCBT | 43.45 | 14.91 | 37.62 | 14.67 | 34.83 | 18.57 |

| VSAU | 44.76 | 12.36 | 45.28 | 18.26 | 47.10 | 17.99 | ||

| LSASa- Avoidance Subscale | 0–72 | WCBT | 40.86 | 17.16 | 29.14 | 15.73 | 30.52 | 19.26 |

| VSAU | 42.83 | 14.68 | 45.24 | 18.61 | 45.83 | 18.35 | ||

| Work-related Social Anxiety – Total | 0–30 | WCBT | 18.72 | 7.42 | 13.21 | 7.10 | 13.31 | 8.38 |

| VSAU | 19.72 | 6.53 | 19.76 | 7.83 | 19.31 | 7.72 | ||

| Work-related Social Anxiety - Anxiety Subscale | 0–15 | WCBT | 10.69 | 3.54 | 8.07 | 3.63 | 7.66 | 4.49 |

| VSAU | 10.55 | 3.29 | 10.48 | 3.92 | 10.62 | 3.63 | ||

| Work-related Social Anxiety - Avoidance Subscale | 0–15 | WCBT | 8.03 | 4.19 | 5.34 | 3.74 | 5.79 | 4.13 |

| VSAU | 9.17 | 3.72 | 9.10 | 4.36 | 8.66 | 4.21 | ||

| BFNEb | 12–60 | WCBT | 46.59 | 12.83 | 39.01 | 13.57 | 35.62 | 13.57 |

| VSAU | 45.00 | 13.19 | 43.07 | 14.48 | 44.00 | 12.57 | ||

| Mini SPINc | 0–12 | WCBT | 6.72 | 2.20 | 7.79 | 2.81 | 7.48 | 3.01 |

| VSAU | 7.52 | 2.87 | 9.66 | 2.58 | 10.28 | 1.28 | ||

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | 0–63 | WCBT | 17.69 | 12.83 | 11.34 | 9.54 | 12.83 | 13.40 |

| VSAU | 22.90 | 14.73 | 24.72 | 17.10 | 22.45 | 14.96 | ||

| PHQ9d Depression Screen | 0–27 | WCBT | 10.59 | 8.08 | 5.62 | 5.49 | 5.83 | 5.74 |

| VSAU | 12.17 | 5.62 | 10.41 | 6.92 | 10.72 | 6.68 | ||

| Sheehan Disability Scale | 0–30 | WCBT | 5.93 | 2.60 | 3.63 | 2.10 | 3.48 | 2.27 |

| VSAU | 6.07 | 2.33 | 4.77 | 2.02 | 5.61 | 2.38 | ||

| SCIDe Social Phobia Symptom Severity | 1–3 | WCBT | 2.07 | 0.65 | 1.31 | 0.81 | 1.28 | 0.84 |

| VSAU | 2.10 | 0.62 | 2.17 | 0.66 | 2.21 | 0.73 | ||

| Clinician Global Impressions - Symptom Severity | 1–7 | WCBT | 4.59 | 1.52 | 3.76 | 1.35 | 3.21 | 1.35 |

| VSAU | 4.24 | 0.99 | 4.14 | 1.27 | 4.21 | 1.37 | ||

| Job Search Self-efficacy Scale | 6–30 | WCBT | 22.62 | 6.24 | 23.31 | 5.37 | 24.31 | 5.70 |

| VSAU | 19.03 | 6.69 | 18.48 | 5.26 | 17.90 | 5.38 | ||

| Job Search Activities (if employed < 20 hrs./wk only) | 10–60 | WCBT | 30.38 | 11.44 | 34.05 | 14.30 | 31.38 | 8.68 |

| VSAU | 26.41 | 10.80 | 33.16 | 8.39 | 25.33 | 6.48 | ||

| Hrs. Worked per Week | N/A | WCBT | 0.00 | 0.00 | 11.90 | 19.81 | 16.10 | 10.49 |

| VSAU | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.14 | 7.22 | 14.69 | 10.29 | ||

Total N = 58; Intervention n = 29; Control n = 29

Liebowitz social anxiety scale;

Brief fear of negative evaluation scale;

Mini social phobia inventory;

Patient health questionnaire;

Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis-1 disorders

Outcomes by Condition over Time

Results of 3-level MLM on all outcome variables are shown in Table 3. Tabled results are from MLM with FU set as the intercept term; results of alternative MLM with PT as the intercept were very similar, indicating that WCBT effects had emerged as significant by PT and were maintained through FU. Coefficients were negative for all mental health measures, indicating lower FU means and more rapidly declining scores for WCBT than VSAU. All FU differences between WCBT and VSAU were significant, with large effect sizes ranging from d= −0.86 to −1.37. Within the WCBT condition, mean change from baseline to FU on the LSAS was −19 points (−0.60 SD); for other outcomes, mean change was −10.97 points on the BFNE (−0.86 SD), 4.86 points on the BAI (−0.38 SD), and −4.76 points on the PHQ (−0.59 SD). Coefficients for job search activity and search self-efficacy were significant and positive, indicating higher follow-up levels and greater increases for WCBT than VSAU; effect sizes were large – d=1.12 and 1.20, respectively. Given the small sample size of this pilot study, we did not anticipate condition effects on employment outcomes; as expected, coefficients for work hours were not significant, and the proportion who reported having worked for pay in the 12 weeks prior to FU (44, or 75.9%) did not differ by condition. However, WCBT work hours were higher than VSAU at both PT and FU; at PT, the difference was nearly significant (t(56) = 1.98, p = .06).

Table 3.

Multilevel analysis of condition effects on outcomes over time by cohort groups (3-level multilevel models)

| Condition Effects on Cohort Average Intercepts and Slopes (se) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Intercept (at 3-month follow-up) (df = 12) | Condition x Linear Slope (df = 40) | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| B | se | da | B | se | db | |||

|

|

|

|||||||

| LSASc - Total | −26.06 | ** | (6.59) | −1.10 | −4.26 | ** | (1.54) | −0.95 |

| LSASc - Anxiety Subscale | −10.89 | ** | (3.47) | −0.88 | −1.97 | * | (0.78) | −0.84 |

| LSASc - Avoidance Subscale | −15.34 | *** | (3.33) | −1.36 | −2.34 | ** | (0.83) | −1.08 |

| Work-related Social Anxiety – Total | −5.89 | ** | (1.73) | −0.93 | −0.82 | * | (0.39) | −0.72 |

| Work-related Social Anxiety - Anxiety | ||||||||

| Subscale | −3.14 | ** | (0.90) | −0.97 | −0.50 | * | (0.21) | −0.85 |

| Work-related Social Anxiety – Avoidance Subscale | −2.67 | * | (0.92) | −0.86 | −0.35 | NS | (0.22) | −0.67 |

| BFNEd | −9.85 | ** | (2.91) | −0.95 | −1.91 | * | (1.71) | −0.91 |

| Mini SPINe | −2.74 | *** | (0.60) | −1.37 | −0.53 | *** | (0.15) | −1.61 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | −8.31 | * | (2.97) | −0.87 | −1.01 | NS | (0.70) | −0.56 |

| PHQ9f Depression Measure | −4.60 | ** | (1.37) | −1.20 | −0.67 | * | (0.32) | −0.97 |

| Sheehan Disability Scale | −2.09 | ** | (0.58) | −1.12 | −0.37 | * | (0.14) | −1.23 |

| SCIDg Social Phobia Symptom Severity | −0.96 | *** | (0.19) | −1.35 | −0.15 | ** | (0.05) | −1.07 |

| Clinical Global Impressions - Symptom Severity | −1.06 | ** | (0.31) | −1.04 | −0.20 | * | (0.08) | −0.87 |

| Job Search Self-efficacy | 5.96 | ** | (1.47) | 1.12 | 1.10 | ** | (0.35) | 1.06 |

| Job Search Activities (employed < 2-hrs./wk only) | 7.05 | * | (2.38) | 1.20 | 1.50 | * | (0.63) | 1.70 |

| Hrs. Worked per Week | 1.74 | NS | (2.91) | 0.46 | 0.07 | NS | (0.78) | 0.15 |

Note: 3-level multilevel model reflects time at level 1, with random intercepts set at 3-month follow-up and random linear time slopes. Time is nested within individuals at level 2, and individuals are nested within cohort groups at level 3.

Effect size: d = B/(intercept SD from a 3-level model containing only time and the baseline covariate);

Effect size: d = B/(slope SD from 3-level model containing only time and the baseline covariate);

Liebowitz social anxiety scale;

Brief fear of negative evaluation scale;

Mini social phobia inventory;

Patient health questionnaire;

Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis 1 disorders

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

NS = nonsignificant.

The proportion meeting diagnostic criteria for SAD declined for WCBT from 100% to 82.8% but remained constant at 100% for VSAU; this comparison was statistically significant; x2(1, N = 58) = 5.47, p = .02.

Intervention Fidelity, Acceptability and Process

WCBT treatment fidelity ratings (23 of 56 WCBT sessions rated) yielded an average overall rating of 4.23 (SD=0.66), which is above the within-protocol threshold (Hope et al., 1999). At PT, WCBT participants’ satisfaction with the intervention was high: mean ratings of overall satisfaction (M = 4.92; SD = 1.26) and willingness to recommend to others (M = 4.72; SD = 1.67) were rated as “very satisfied.”

Finally, session attendance was high. Only three individuals (10%) dropped out of WCBT, and the remaining 26 who were assigned to WCBT attended at least five of the sessions; 16 (55%) attended all eight. Mean number of sessions attended was 7.38 (SD = 0.98).

Discussion

The findings from this pilot randomized trial suggest that SAD can be treated using a specialized work-related group CBT led by vocational service professionals in a vocational service center. Confidence that WCBT exerts a significant effect over and above VSAU is supported by significant improvement on all measures of social anxiety, general anxiety, depressive symptoms, overall symptom severity, and measures of functioning. Perhaps more importantly, job-search behaviors and job search self-confidence also significantly improved with WCBT compared to VSAU. Clinical significance was demonstrated by the large effect sizes obtained for WCBT which were comparable to prior studies of CBT for SAD (Acarturk et al., 2009). WCBT participants reported high satisfaction ratings, and retention rates exceeded those reported in most other studies of group CBT for SAD (Acarturk et al., 2009). Finally, WCBT was also delivered with high fidelity to the treatment model.

The results also add to the literature supporting the benefits of vocational service center-based CBT designed to improve mental health symptoms and employment-related variables (Della-Posta & Drummond, 2006; Vinokur et al., 2000). It is also important to note that these promising outcomes were attained with homeless study participants, most of whom suffered from co-occurring mental health and substance-use disorders, had felony convictions and limited educational and vocational attainment histories. WCBT is unique in that it was designed and tested in a mostly minority, impoverished population with an eye toward future dissemination to the majority population which stands in contrast to the common practice of developing interventions in majority populations for later use by underserved groups (Proctor et al., 2009).

WCBT did not significantly improve hours worked per week despite its significant impact on job-search behaviors. Comparison of the average number of hours worked per week between the WCBT and VSAU was nearly significant in favor of WCBT post-intervention, but small sample sizes and limitations with the method of measuring hours worked per week may have been responsible for this outcome. The main limitation of the hours worked per week measure was that it relied on participants’ ability to recall average number of hours worked over the 12-week follow-up period which was likely difficult for those working irregular schedules.

Although this trial has many important strengths, there are also limitations that set the stage for future study of WCBT. First, in keeping with the community-based, effectiveness design, WCBT participants received 16 hours of additional attention from vocational service professionals over those assigned to VSAU. Given that SAD has not been found to be responsive to attention placebo conditions (Acarturk et al., 2009), it is not likely that the effects of WCBT result primarily from the additional time with providers as opposed to CBT-specific content, but this is uncertain. Second, given that many mental health symptoms improved along with social anxiety for those assigned to WCBT, it is possible that symptom change other than change in social anxiety mediated the effect of WCBT on employment related variables. Our sample size did not allow for examination of these potential mediation effects, indicating the need for future large-scale studies of WCBT. Third, improvements in social anxiety symptoms, although statistically significant, still left several members with moderate symptom levels post-WCBT, suggesting that a longer course of WCBT might be indicated. Fourth, the relatively short follow-up period did not provide the opportunity to evaluate employment and mental health effects over the long term. Clearly, future long-term studies of WCBT are needed. Fifth, modest weekly incentives for transportation and completing weekly assessments may have influenced WCBT retention although this is uncertain. Finally, the sample presented minimal variability on race-ethnicity, prior employment, and other demographic characteristics and as such we found no significant effect differences for any of these or other potential moderators, including psychiatric comorbidities and psychotropic medication use. Future investigations using larger and more diverse samples would provide more definitive tests of moderator effects.

The above limitations notwithstanding, the study has several important strengths including: its unique sample; significant improvements on all social anxiety and mental health symptom assessments; significant improvements in employment-related variables; strong WCBT participant retention; and a sustainable intervention that can be delivered with fidelity by vocational service professionals. Finally, we believe that WCBT’s focus on social anxiety is particularly timely given that our economy is becoming more service-based (U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2005) and is producing jobs in which the ability to comfortably and skillfully interact with others is particularly important.

Work-Related Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (WCBT) is highly accepted

WCBT was delivered successfully in an impoverished, minority, unemployed sample

WCBT improves social anxiety, general anxiety and depression over care as usual

WCBT increases job-seeking behavior WCBT increases job-search self-confidence

Acknowledgments

This research was support by the National Institute of Mental Health grant R34MH083031 awarded to Dr. Himle. ClnicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01654510.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acarturk C, Cuijpers P, van Straten A, de Graaf R. Psychological treatment of social anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:241–254. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Bijl RV, Lin E, Walters EE, Kessler RC. Income differences in persons seeking outpatient treatment for mental disorders: A comparison with Ontario and the Netherlands. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:383–391. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Relationship between the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale with anxious outpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1991;5:213–223. doi: 10.1016/0887-6185(91)90002-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Heimberg RG, Schneier FR, Fresco DM, Chen H, Turk CL, Liebowitz MR. A placebo-controlled trial of phenelzine, cognitive behavioral group therapy and their combination for social anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:286–295. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin D, Collins K, Papageorgis S. Reducing clients' reliance on long-term sickness benefits: Debra Brewin and colleagues discuss a community programme that combines cognitive behaviour therapy with employment support to help service users find jobs. Mental Health Practice. 2011;15:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bruch MA, Fallon M, Heimberg RG. Social phobia and difficulties in occupational adjustment. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2003;50:109–117. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.50.1.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Kobak KA, Churchill LE. MINI-SPIN: A brief screening assessment for generalized social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;14:137–140. doi: 10.1002/da.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della-Posta C, Drummond PD. Cognitive behavioural therapy increases re-employment of job seeking worker’s compensation Clients. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2006;16:223–230. doi: 10.1007/s10926-006-9024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Patient Edition (SCID-I/P. Version 2.0) New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment for Psychopharmacology, Revised Edition. Rockville, MD: NIMH Publication; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Becker RE. Cognitive behavioral group therapy for social phobia: Basic mechanisms and clinical strategies. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hope DA, VanDyke M, Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Fresco DM. In: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder: Therapist adherence scale. Heimberg Richard G., editor. Department of Psychology, Temple University; 1999. Unpublished manuscript available. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:601–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagerveld SE, Blonk RWB. Work-focused treatment of common mental disorders and return to work: A Comparative outcome study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2012;17:230–234. doi: 10.1037/a0027049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. A brief version of the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1983;9:371–375. doi: 10.1177/0146167283093007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levine DS, Himle JA, Vlnka S, Steinberger E, Laviolette WT, Bybee D. Effectiveness of the Mini-Social Phobia Inventory (Mini-SPIN) as a screener for social anxiety disorder in a low-income, job-seeking sample. 2013. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–173. doi: 10.1159/000414022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moitra EB, Weisberg C, Keller RB, Martin B. Occupational impairment and social anxiety disorder in a sample of primary care patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;130:209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherance. Medical Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW, Caldwell C, Williams DR, Nesse R, Taylor RJ, Bullard KM, Jackson JS. Race, ethnicity, and the use of services for mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:485–494. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2009;36:24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R. HLM 7: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Chicago: Scientific Software International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Liu XF. Effects of study duration, frequency of observation, and sample size on power in studies of group differences in polynomial change. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:387–401. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. doi: 10.1037//1082-989X.7.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;11:89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Kean YM. Disability and quality of life in social phobia: Epidemiologic findings. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1606–1603. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman R, Himle J, Bybee D, Abelson J, Hoffman J, Van Etten-Lee M. Impact of social anxiety disorder on employment among women receiving welfare benefits. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:61–66. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SM, Beidel DC, Dancu CV, Keys DJ. Psychopathology of social phobia and comparison to avoidant personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95:389–394. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.95.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Editor's Desk: Service-providing sector and job growth to 2014. 2005 from http://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2005/dec/wk3/art01.htm.

- Vinokur AD, Schul Y, Vuori J, Price RH. Two years after a job loss: Long term impact of the JOBS program on reemployment and mental health. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2000;5:32–47. doi: 10.1037//1076-g998.5.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelvemonth use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Fuetsch M, Sonntag H, Muller N, Liebowitz M. Disability and quality of life in pure and comorbid social phobia. Findings from a controlled study. European Psychiatry. 2000;15:46–58. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(00)00211-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaider TI, Heimberg RG, Fresco DM, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. Evaluation of the Clinical Global Impression Scale among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:611–622. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703007414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]