Abstract

Background. Severe gram-negative bacterial infections and sepsis are major causes of morbidity and mortality. Dysregulated, excessive proinflammatory cytokine expression contributes to the pathogenesis of sepsis. A CD28 mimetic peptide (AB103; previously known as p2TA) that attenuates CD28 signaling and T-helper type 1 cytokine responses was tested for its ability to increase survival in models of polymicrobial infection and gram-negative sepsis.

Methods. Mice received AB103, followed by an injection of Escherichia coli 0111:B4 lipopolysaccharide (LPS); underwent induction E. coli 018:K1 peritonitis induction, followed by treatment with AB103; or underwent cecal ligation and puncture (CLP), followed by treatment with AB103. The effects of AB103 on factors associated with and the lethality of challenge infections were analyzed.

Results. AB103 strongly attenuated induction of tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin 6 (IL-6) by LPS in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Receipt of AB103 following intraperitoneal injection of LPS resulted in survival among 73% of CD1 mice (11 of 15), compared with 20% of controls (3 of 15). Suboptimal doses of antibiotic alone protected 20% of mice (1 of 5) from E. coli peritonitis, whereas 100% (15 of 15) survived when AB103 was added 4 hours following infection. Survival among mice treated with AB103 12 hours after CLP was 100% (8 of 8), compared with 17% among untreated mice (1 of 6). In addition, receipt of AB103 12 hours after CLP attenuated inflammatory cytokine responses and neutrophil influx into tissues and promoted bacterial clearance. Receipt of AB103 24 hours after CLP still protected 63% of mice (5 of 8).

Conclusions. Single-dose AB103 reduces mortality in experimental models of polymicrobial and gram-negative bacterial infection and sepsis, warranting further studies of this agent in clinical trials.

Keywords: CD28 homodimer interface, mimetic peptide, peritonitis, gram-negative sepsis, cecal ligation and puncture, lipopolysaccharide

Severe gram-negative bacterial infections, including sepsis, are a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. Despite the availability of potent antimicrobial agents and advances in supportive care, mortality from sepsis has persisted at >20% [2]. Consequently, there have been concerted efforts to develop agents that can either neutralize bacterial virulence factors and/or enhance host defenses that, in conjunction with antibiotic therapy, may improve the outcome from these infections.

Optimal T-cell responses require not only an interaction between the T-cell receptor (TCR) and major histocompatibility complex class II on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), but also costimulatory signaling through CD28 expressed on the T cell and B-7 coligands (CD80 and CD86) on APCs. We developed a novel, host-oriented therapeutic approach to provide broad protection against gram-positive bacteria and their exotoxins in which peptides target CD28, the principal human costimulatory receptor, to prevent the excessive, harmful inflammatory cytokine response underlying infection pathology [3, 4]. AB103 (previously known as p2TA) is an octapeptide derived from the homodimer interface of CD28, which is essential for the induction of many proinflammatory cytokines, that attenuates signaling through CD28 [3]. CD28 also functions as a critical superantigen receptor [3, 4]. AB103/p2TA blocks not only superantigen-mediated lethality in mice, but also lethal group A Streptococcus pyogenes infection [3, 5]. The finding that AB103 attenuates the inflammatory immune response to gram-positive bacterial infection [5] suggested that the peptide might be capable of intervening also with downstream signaling of CD28 in cases of severe bacterial infection that are not directly mediated by superantigens.

Recent evidence indicates that blockade of costimulatory signals, including CD40 and/or CD80/86, might reduce mortality in experimental intra-abdominal sepsis [6]. We therefore tested the ability of this CD28 mimetic peptide to protect mice from lethal experimental sepsis. We now demonstrate that AB103 potently reduces the induction of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and protects mice from lethality following intraperitoneal LPS or gram-negative bacterial challenges, as well as in the cecal ligation/puncture (CLP) model of polymicrobial sepsis.

METHODS

Reagents

Chemical reagents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise stated. The test agent, AB103, is a peptide with the sequence SPMLVAYD that has D-alanine residues abutted to its N- and C-termini for greater protease resistance [3]. A peptide with a randomly scrambled sequence, ASMDYPVL, served as a control [3]. Peptides and vehicle control buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) were provided by Atox Bio. Escherichia coli LPS 0111:B4 obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis) and from List Biological Laboratories (Campbell, CA) was used for studies involving human PBMCs and mice, respectively. We used E. coli O18:K1:H7, a highly virulent, serum-resistant, clinically isolated gram-negative bacterial isolate for the peritonitis studies [7].

Animals

Specific-pathogen-free female BALB/c and CD1 outbred mice aged 8–12 weeks were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). All animal studies were approved by the Brown University/Rhode Island Hospital and University of Maryland institutional animal care and use committees (IACUCs) before experiments were initiated. Animals were housed in an IACUC-approved facility under biosafety level 2 safety conditions and were monitored by Brown University/Rhode Island Hospital and University of Maryland veterinary staffs.

Human PBMCs and Cytokine Induction by LPS

PBMCs from healthy human subjects were prepared under a Hebrew University Institutional Review Board–approved protocol described elsewhere [3, 8] and were cultured at 1 × 106 cells/mL in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium [3, 8]. Cells were allowed to rest at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 4 hours. After LPS stimulation of cells in the presence or absence of AB103/p2TA, culture medium was collected at intervals for triplicate evaluation of cytokines by an enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) [3, 8].

LPS Challenge

CD1 or BALB/c mice were administered 20 mg D-galactosamine (D-galN) intraperitoneally, followed in 2 hours by 0.25 mg/kg E. coli 0111:B4 LPS. AB103 was injected intraperitoneally 30 minutes before LPS.

E. coli Peritonitis

Acute bacterial peritonitis was induced by intraperitoneal challenge of BALB/c mice with E. coli 018:K1 (1 × 105 colony-forming units [CFU]), followed by intravenous therapy with either AB103 or saline 4 hours after challenge. The protective ability of AB103 was tested following the induction of E. coli peritonitis in the presence of a suboptimal dose of the antibiotic cefepime (Elan).

CLP Model of Polymicrobial Sepsis

The murine CLP model of polymicrobial sepsis has been detailed elsewhere [9]. Moxifloxacin (Schering) was given either at 5 mg/kg (suboptimal dose) or 20 mg/kg (full therapeutic dose, usually providing approximately 90% survival when given at the time of surgery). Animals that underwent sham surgery were handled in the identical fashion except that, after laparotomy, the exposed cecum was not ligated or punctured.

We tested the efficacy of AB103 administered 2, 12, or 24 hours after CLP. Moribund animals (defined as animals that were hypothermic [temperature, <30°C] and unable to maintain normal body posture) were euthanized and scored as lethally infected animals. Another set of mice were euthanized at prespecified periods after CLP and underwent quantitative microbiologic analysis of cytokines and chemokines in blood specimens, peritoneal fluid specimens, and organ tissues (liver, kidneys, and spleen).

Sample Preparation

Twelve or 24 hours after the procedure, mice were euthanized, and splenocytes were obtained by gently grinding splenic tissues between frosted glass slides [10]. Splenocytes were then centrifuged, counted by trypan blue exclusion, and used for analyses. Blood specimens were collected in heparinized syringes by cardiac puncture, and plasma specimens were obtained by centrifugation. Peritoneal fluid specimens were obtained from mice by lavage and clarified by centrifugation [11].

Cytokine and Chemokine Levels in Plasma and Tissues

Mouse TNF-α, monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), IL-6, interleukin 10 (IL-10), interleukin 2 (IL-2), interleukin 4, and interferon γ (IFN-γ) levels were determined in plasma or peritoneal fluid specimens, using the cytometric bead array technique (BD Cytometric Bead Array Mouse Inflammation Kit, BD Biosciences). Keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC), RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), interleukin 3 (IL-3; BD Biosciences), and interleukin 17A (Biolegend) levels were measured in plasma, peritoneal fluid, or tissue homogenates by ELISA, using monoclonal antibody pairs and mouse cytokine standards [12].

Macrophages and Phagocytosis Assay

Peritoneal macrophages were harvested as described previously [13]. Adherent macrophages were cocultured with pHrodo BioParticles–conjugated E. coli (Molecular Probes) in PBS at 37°C for 1 hour and then were washed with PBS. Cells were scraped from the plates and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Systemic and Tissue Bacterial Levels

Organs were sterilely excised from euthanized animals, weighed, and minced by agitation in minifuge tubes with glass beads. The resulting suspension was serially diluted in PBS prior to plating on Trypticase soy agar (TSA) plates and McConkey agar. After overnight incubation at 37°C, the number of CFU per milligram of tissue was calculated for each sample.

Blood samples (50 or 100 µL) were spread on TSA with 5% sheep blood. One milliliter of PBS was injected into the peritoneum, and peritoneal lavage fluid was harvested and serially diluted in sterile PBS. A 100-µL aliquot of each dilution was spread on a TSA plate, and plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Colonies were calculated as CFU/mL, for blood samples, or as CFU × 104/mL, for peritoneal lavage samples [13].

Assessment of Myeloperoxidase (MPO) Activity

MPO activity was determined [14] on homogenized tissues added to the reaction mixture in a 96-well plate. Plates were read at 460 nm every minute for 10 minutes. MPO activity was calculated as A460 × 13.5/g, where A460 is the rate of change in absorbance.

Statistical Analysis

For continuous variables, results are presented graphically as mean values ± standard errors of the mean for each group, except for data shown in Figure 1. Statistical comparisons of mean values for continuous variables were performed using the 2-sided randomization test [15] on the t statistic for unequal variances, with either exact P values (for sample sizes of ≤4) or P values, based on 100 000 random samples from the data. Proportions of mice surviving at the end of an experiment were compared by a 2-sided Fisher exact test; when sample sizes were unequal, the 2-sided P value was calculated as twice the smaller 1-sided P value [16], since, for unequal sample sizes, the probabilities in the 2 tails are not equal. A P value of ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons.

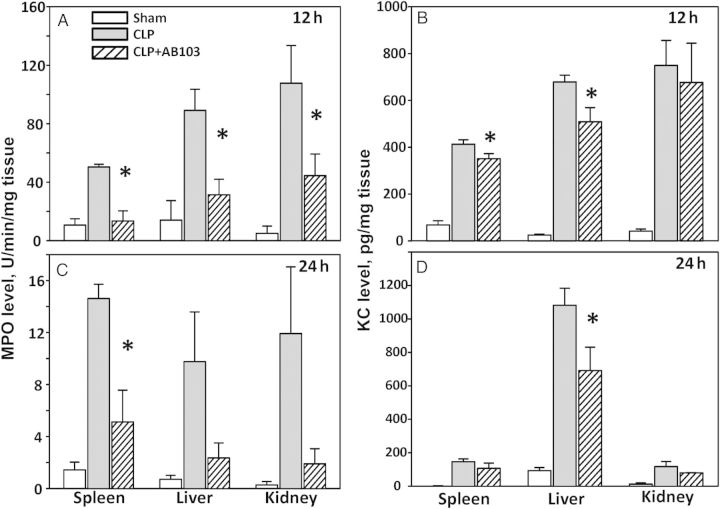

Figure 1.

Peptide AB103 blocks induction of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Human PBMCs were stimulated with 0.1 µg/mL LPS alone (○) or in the presence of 0.1 (▴), 1 (♦), or 10 µg/mL (▪) of AB103 added 10 minutes prior to stimulation with LPS. At the indicated times, secreted levels of TNF-α (A) and, in a separate experiment, IL-6 (B) were assayed. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). See also Supplementary Figure 1.

RESULTS

AB103 Attenuates the LPS Response in Human PBMCs

Human PBMCs were treated with increasing doses of AB103 and exposed to LPS to examine whether induction of TNF-α (Figure 1A) or IL-6 (Figure 1B) was inhibited. Cells treated with LPS alone had a strong TNF-α response, which increased for at least 6 hours after treatment. Treatment of PBMCs with AB103 at the time of LPS stimulation attenuated TNF-α production, roughly in a dose-dependent manner. The TNF-α response declined perceptibly in cells pretreated with a low dose of AB103 (0.1 µg/mL), compared with cells that received only LPS stimulation. Moreover, the level of TNF-α induced in LPS-stimulated cells treated with AB103 at either 1.0 or 10 µg/mL was reduced strongly for the duration of the experiment to levels close to the baseline. A similar pattern of inhibition was observed for IL-6 induction. The action of AB103 was specific. Random scrambling of the amino acid sequence of AB103 fully abrogated its antagonist activity (Supplementary Figure 1A). Cells treated with AB103 alone, without LPS, did not produce detectable TNF-α (Supplementary Figure 1B) or IL-6 (data not shown), showing that the peptide lacks agonist activity.

AB103 Protects Mice Against LPS Challenge

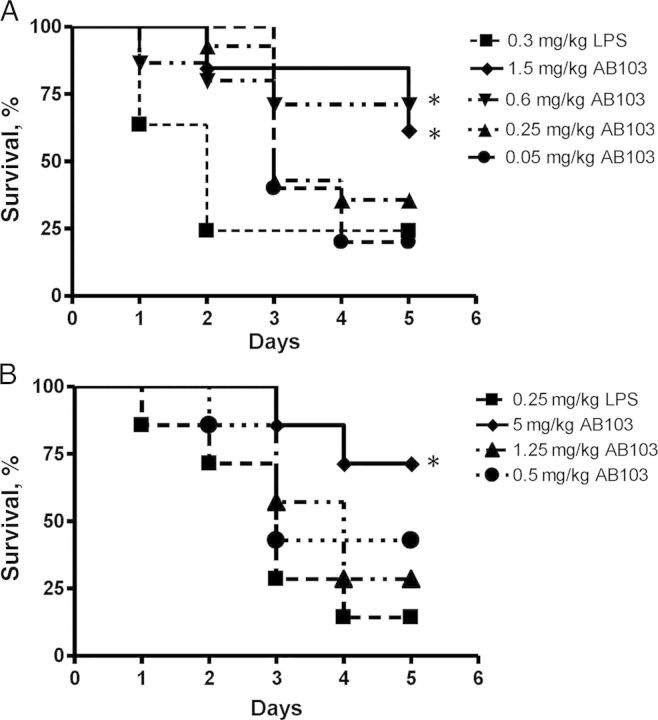

We next tested the ability of AB103 to reduce LPS-induced lethality in vivo in a D-galN–sensitized CD1 mouse model. At termination, survival of the group treated with 0.6 mg/kg AB103 30 minutes before LPS challenge was 73% (11 of 15), compared with 20% (3 of 15) in the LPS-alone control group (P = .0095), while the group treated with 1.5 mg/kg AB103 had a 60% survival rate (9 of 15 animals; P = .06; Figure 2A). No significant difference in survival was observed between the control group and either of the 2 groups that received the lowest doses (0.25 and 0.05 mg/kg) of the peptide. The survival rates of the groups that were administered the peptide 1 and 5 hours after LPS challenge were also similar to the LPS-alone control group (data not shown). All 5 mice that received the peptide alone in the absence of LPS survived (data not shown).

Figure 2.

AB103 improves survival after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge. Survival proportions in CD1 outbred mice (A) or BALB/c mice (B). The mice (15 mice/group) were administered 20 mg of D-galN intraperitoneally before challenge 2 hours later with 0.3 mg/kg (A) or 0.25 mg/kg (B) of LPS intraperitoneally. AB103 was injected intraperitoneally (A) or intravenously (B) at increasing doses in volumes of 0.2 mL as indicated, 30 minutes before challenge with LPS. The control group (▪) was challenged intraperitoneally with LPS but did not receive the peptide. AB103 (0.6 mg/kg and 1.5 mg/kg) protected CD1 mice (P = .009 and P = .06, respectively; A) and 5 mg/kg of AB103 protected BALB/c mice (P = .003) against LPS at 5 days, as determined by a 2-sided Fisher exact test (B). An asterisk indicates significantly higher survival than in control mice.

The protective effect was not restricted to CD1 mice. BALB/c mice that received a sufficiently high dose of AB103 were also protected against lethal LPS challenge (Figure 2B). Over 85% of mice that did not receive the peptide died within 5 days of challenge. Compared with a survival rate of 13% (2 of 15) in the LPS control group, 73% of mice (11 of 15) pretreated with 5 mg/kg (P = .003) and 47% (7 of 15) that received 0.5 mg/kg (P = .11) survived. Five days after challenge, 29% of mice that received 1.25 mg/kg AB103 survived.

AB103 Protects Against E. coli Peritonitis

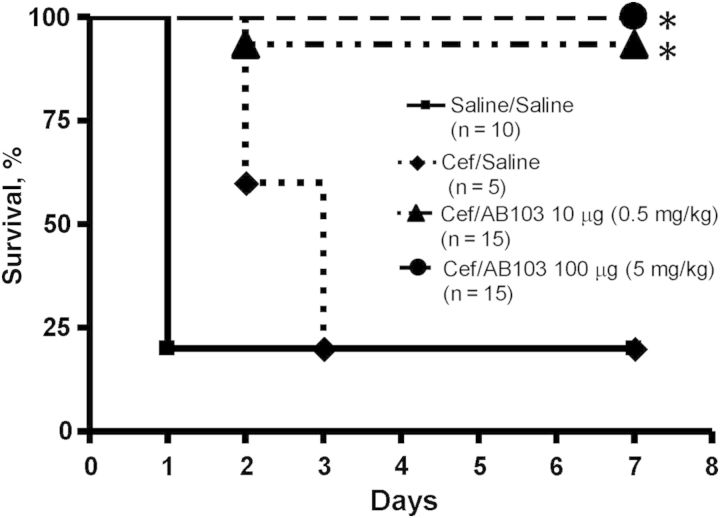

The ability of AB103 to increase survival of BALB/c mice following infection with replicating bacteria was studied in an E. coli peritonitis model (Figure 3). A mortality rate of 80% was observed in mice treated, in the absence of AB103, with saline alone or with a suboptimal dose of cefepime. When given a single dose of AB103 intravenously in combination with the same dose of cefepime, 100% of mice (15 of 15) receiving a dose of 5 mg/kg AB103 and 93% of mice (14 of 15) treated with 0.5 mg/kg AB103 survived (P < .001 for both AB103 groups, compared with saline-treated controls; P = .001 and P = .005, respectively for AB103, compared with cefepime). AB103 alone has no bactericidal activity.

Figure 3.

AB103 protects against lethal Escherichia coli O18:K1 peritonitis. AB103 (0.5 mg/kg or 5 mg/kg) was given intravenously in 0.2 mL with antibiotics (cefepime [Cef] 5 mg/kg intramuscularly) 4 hours after E. coli challenge. The number of mice/group is given in parentheses. Both AB103-treated groups had a significantly greater survival rate than did mice receiving phosphate-buffered saline control or Cef alone, as indicated by an asterisk.

Effectiveness of AB103 in the CLP Model of Sepsis

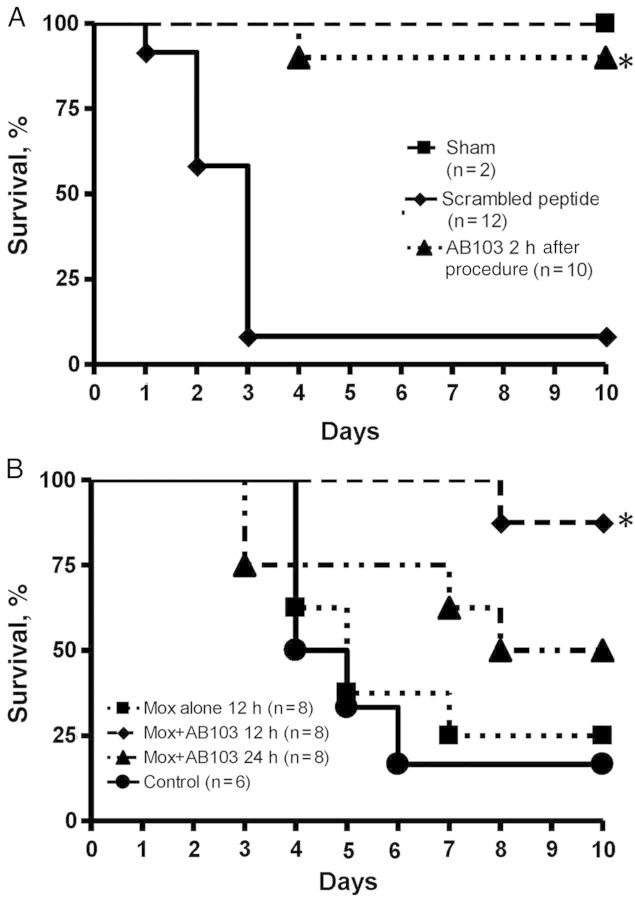

In a first set of CLP experiments, a single dose of AB103 was administered at the time of surgery, without antibiotics, and 16 of 21 animals (76%) survived for the 7-day study period after surgery (data not shown).

Random scrambling of the AB103 peptide sequence abrogates its antagonist activity, as manifested by loss of the ability to block the induction of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-2 genes in human PBMCs by superantigen toxin, to bind superantigen, or to protect mice from lethal superantigen challenge [3]. When a suboptimal dose of moxifloxacin was given at the end of surgery, along with scrambled peptide 2 hours after CLP, only 8% (1 of 12) survived. However, when administered together with 1 dose of AB103, survival increased to 90% (9 of 10) at day 7 (P < .001; Figure 4A). Thus, a single dose of AB103 administered 2 hours after exposure of mice to polymicrobial infection sufficed to provide a high level of protection.

Figure 4.

A single dose of AB103 improves survival after cecal ligation/puncture (CLP). Delayed administration of AB103 (5 mg/kg intravenously in 0.2 mL) was compared along with scrambled peptide (n = 4)/phosphate-buffered saline (n = 8) controls and sham animals. The number of mice/group is given in parentheses. Mice treated with AB103 intravenously 2 hours after CLP with a suboptimal dose moxifloxacin (at a 20% effective dose of 5 mg/kg intramuscularly, usually providing approximately 20% survival when given at the time of infection) had significantly higher survival at 7 days than the moxifloxacin plus scrambled peptide control group (P < .001; A). Mice treated with AB103 plus moxifloxacin (20 mg/kg) 12 hours after CLP had significantly higher survival at 7 days than control mice (P = .006; B). An asterisk indicates significantly higher survival than in control mice.

We next evaluated the duration of time that could pass between CLP and initiation of AB103 treatment that protected mice from infection (Figure 4B). When animals subjected to CLP were left untreated, most (83% [5 of 6]) died within 3–6 days. When animals were treated with moxifloxacin alone 12 hours after infection, survival did not change substantially (25% [2 of 8] at 7 days), indicating that addition of antibiotics alone was not beneficial. However, treatment of animals with a combination of antibiotics and AB103 12 hours after CLP resulted in 100% survival (8 of 8 at 7 days; 1-sided P = .003, compared with control mice). If AB103 treatment was delayed to 24 hours after CLP (while antibiotic was still given at 12 hours), the survival rate at 7 days was 63% (5 of 8; 1-sided P = .12, compared with control mice), which was substantially but not significantly higher than survival after treatment with antibiotics alone (1-sided P = .16). These results indicate that under conditions where antibiotic treatment alone is insufficient, AB103 acts synergistically and can improve survival even at late time points in the infection.

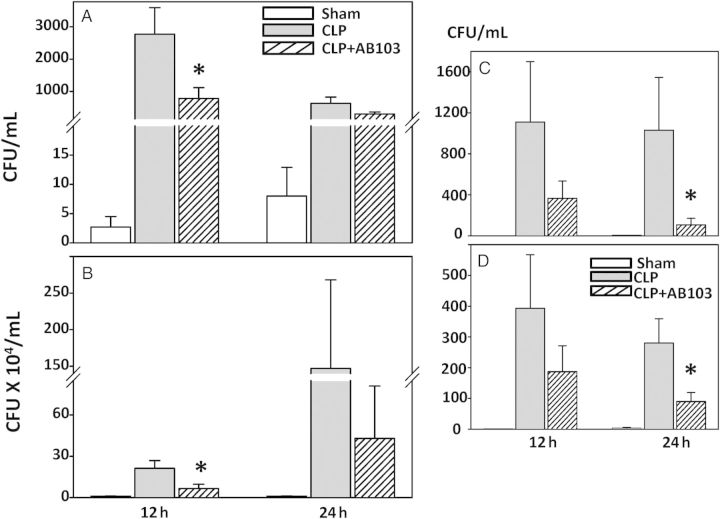

AB103 Increases Systemic and Peritoneal Bacterial Clearance Following CLP

Mean levels of bacteria grown from blood specimens, peritoneal fluid specimens, liver, and kidneys obtained 12 and 24 hours after CLP were lower in the groups that received AB103, compared with the control group. In blood, substantial reduction was detected by 12 hours (P = .045; Figure 5A), but the mean values were closer at 24 hours (P = .085). In peritoneal fluid (Figure 5B), the reduction was again significant at 12 hours (P = .030) but not at 24 hours (P = .46), even though it was larger in absolute value at 24 hours. In other key organs (ie, the liver [Figure 5C] and kidney [Figure 5D]), reduction in the bacterial count was significant at 24 hours (P < .05) but not 12 hours after CLP. A trend of increased bacterial clearance was also detected in the spleen (data not shown). Overall, these results indicate that treatment with AB103 is associated with increased clearance of bacteria from the site of infection in the peritoneum and blood, as well as in other organs enriched with macrophages.

Figure 5.

AB103 promotes bacterial clearance from blood (A), peritoneum (B), and tissues (liver [C] and kidneys [D]) after cecal ligation/puncture (CLP). Mice that received a single dose of AB103 (5 mg/kg 2 hours after CLP in 0.2 mL) were compared to mice treated with CLP and no AB103 and mice that underwent sham surgery. None of the animals received antibiotics. Mice were euthanized 12 and 24 hours after surgery, and tissue samples were obtained from each animal. Levels of bacteria were measured by colony count and compared between treated and control groups. An asterisk indicates significantly reduced bacterial load after CLP in mice treated with AB103 compared with CLP-treated controls. Mean values ± standard errors of the mean are shown (n = 5–8 mice/group). Abbreviation: CFU, colony-forming units.

AB103 Limited Neutrophil Influx and Reduced KC Levels Following CLP

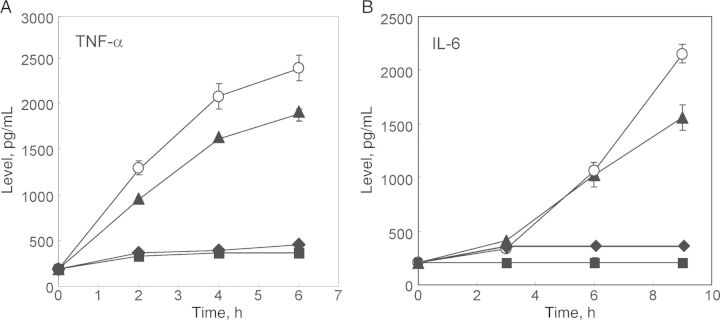

Recruitment of neutrophils to tissue beds has been proposed to contribute to local tissue injury. CD28-deficient mice exhibit a reduction in neutrophil recruitment into the kidney and improved renal function during endotoxemia [17]. We therefore measured the effect of AB103 on neutrophil recruitment after CLP in the spleen, liver, and kidneys. At both 12 and 24 hours after CLP, treatment with AB103 reduced MPO levels in all tissues, compared with findings for CLP-treated mice (Figure 6A and 6B). The differences were statistically significant in the spleen at 12 and 24 hours and in the liver at 12 hours.

Figure 6.

AB103 reduces neutrophil recruitment as assessed by myeloperoxidase (MPO) enzymatic activity and keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC) levels in tissues after cecal ligation/puncture (CLP). AB103 significantly reduced MPO activity, compared with vehicle control–treated mice in the spleen, 12 hours (P = .002; A) and 24 hours (P = .029; B) after CLP and in the liver and kidneys 12 hours (P = .004; A) but not 24 hours after CLP. AB103 significantly reduced KC levels in the spleen 12 hours after CLP (P = .017; C) and the liver 12 hours (P = .037; C) and 24 hours (P = .027; D) after CLP but not in the kidney, compared with findings in vehicle-treated mice after CLP. An asterisk indicates statistical significance for CLP + vehicle vs AB103-treated CLP. Mean values ± standard errors of the mean are shown (n = 5–8 mice/group).

Additionally, the levels of KC, a murine chemokine homologue of human interleukin 8, a potent neutrophil chemoattractant, were measured at 12 and 24 hours in the spleen, liver, and kidneys. Treatment with AB103 significantly reduced KC levels in the spleen at 12 hours and the liver at 12 and 24 hours but not in the kidneys, compared with findings for CLP-treated control mice (Figure 6C and 6D).

Cytokine and Chemokine Levels in Peritoneum and Blood Following CLP

While treatment with AB103 yielded a general reduction in the peritoneum of all but one of the cytokines and chemokines 12 and 24 hours after CLP (MCP-1 at 12 hours was the exception), the differences were significant only for TNF-α at 24 hours and for KC at 12 hours (and nearly so for RANTES at 24 hours and IL-3 at 12 hours), compared with findings for vehicle-treated control mice (Table 1). AB103 had no apparent effect on CLP-induced increases in levels of cytokines or chemokines in plasma at either 12 or 24 hours following CLP.

Table 1.

Cytokine and Chemokine Levels in Peritoneal Fluid Samples Obtained From Mice 12 or 24 Hours After Sham Surgery, Cecal Ligation/Puncture (CLP) Plus Vehicle Treatment, or CLP Plus AB103 Treatment

| Cytokine/Chemokine, Time Point | Sham | CLP + Vehicle | CLP + AB103 |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | |||

| 12 h | 9 ± 3 | 276 ± 43 | 235 ± 33 |

| 24 h | 1 ± 1 | 174 ± 33 | 51 ± 13a |

| RANTES | |||

| 12 h | 8 ± 0 | 163 ± 22 | 121 ± 22 |

| 24 h | 4 ± 2 | 165 ± 41 | 74 ± 15b |

| KC | |||

| 12 h | 0 ± 0 | 154 ± 10 | 120 ± 5a |

| 24 h | 1 ± 0 | 30 ± 4 | 25 ± 1 |

| IL-17A | |||

| 12 h | 0 ± 0 | 144 ± 43 | 111 ± 58 |

| 24 h | 1 ± 1 | 214 ± 63 | 118 ± 38 |

| IL-3 | |||

| 12 h | 7 ± 3 | 99 ± 23 | 37 ± 12a |

| 24 h | 7 ± 3 | 82 ± 74 | 14 ± 15 |

| MCP-1 | |||

| 12 h | 520 ± 117 | 6317 ± 1005 | 6684 ± 987 |

| 24 h | 91 ± 20 | 2344 ± 606 | 1265 ± 544 |

| IL-10 | |||

| 12 h | 15 ± 5 | 440 ± 119 | 338 ± 119 |

| 24 h | 8 ± 3 | 165 ± 63 | 142 ± 71 |

| IL-6 | |||

| 12 h | 295 ± 59 | 8046 ± 919 | 7946 ± 1202 |

| 24 h | 30 ± 12 | 4294 ± 759 | 4040 ± 853 |

Data are mean pg/mL (±standard error of the mean), with 5–8 mice/group.

Abbreviations: IL-3, interleukin 3; IL-6, interleukin 6; IL-10, interleukin 10; IL-17A, interleukin 17A; KC, keratinocyte-derived chemokine; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; RANTES, regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

a P ≤ .05, vs vehicle-treated CLP group (TNF-α: P = .008; KC: P = .023; IL-3: P = .050).

b P = .056. All other P values > .23).

Phagocytosis assays did not detect any important differences between the presence or absence of AB103, nor did AB103 treatment significantly change CD28 expression by peripheral blood and spleen T cells or Gr-1–positive cells, compared with findings for vehicle-treated controls (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We have shown that a CD28 mimetic peptide, AB103, designed to attenuate CD28 signaling, is highly effective in animal models of endotoxin-initiated toxicity and of sepsis that included infection with live, replicating, gram-negative bacteria (E. coli) and polymicrobial infection (CLP). We also found that addition of AB103 to PBMCs ex vivo potently reduced the LPS-mediated induction of TNF-α and IL-6 (Figure 1). AB103 was protective when given alone (70% survival rate in the CLP model) at the time of infection or as a delayed treatment after infection, with suboptimal doses of antibiotics, achieving 100% protection against E. coli peritonitis and 86% survival in the CLP sepsis model (Figures 3 and 4). Remarkably, AB103 was still effective even when given up to 12 and 24 hours following CLP (100% and 50% survival, respectively).

AB103 is derived from the homodimer interface of the costimulatory receptor CD28 [3], which is expressed primarily on CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes, the sources of many inflammatory cytokines. Unlike TGN1412, an agonist monoclonal antibody that cross-links the CD28 coreceptor and caused a cytokine storm and organ failure in a phase 1 clinical trial study [18], AB103 is an antagonist peptide that reduces signaling through CD28 and attenuates the dysregulated cytokine production following superantigen toxin exposure [3] or gram-positive bacterial challenge [5] without triggering a cytokine response by itself in PBMCs. Indeed, even when administered at a dose 125-fold greater than that needed to protect mice from lethal challenge with staphylococcal enterotoxin B, AB103 by itself did not affect the viability of mice [3]. Further, attenuating CD28 signaling [3] with a superantigen mimetic peptide [8, 19] or with AB103 [5] did not abrogate humoral or cell-mediated immune responses.

The functional role of the B7-CD28 axis in LPS-mediated toxicity is understood incompletely, but it has become increasingly clear that B7/CD28 costimulation and T cells are important elements in the pathophysiology of septic shock [6]. LPS is a potent adjuvant of the T-helper type 1 (Th1) response that acts indirectly on T cells (clonal expansion, long-term survival, IFN-γ production, and migration to nonlymphoid tissue) [6, 14, 17], possibly through its ability to induce expression of IL-12 family cytokines in APCs through activation of TLRs [6]. However, it is plausible that the primary action of the peptide is to inhibit induction of Th1 cytokines, because a full inhibitory effect of AB103 on TNF- α and IL-6 induction was observed promptly, within hours after exposure of PBMCs to LPS (Figure 1).

Our results strongly suggest that LPS toxicity is mediated not only by upstream TLR4 signaling, but also by downstream signaling involving the costimulatory receptor CD28. Although the ability of murine T cells to respond directly to LPS is still poorly understood, supporting evidence for involvement of T cells and CD28 in LPS-mediated activity comes from a number of human and murine studies. First, LPS upregulates myeloid costimulatory molecules, such as CD40 and B7 (ie, CD80 and CD86), through a MyD88-independent pathway [6]. These costimulatory molecules then engage T-cell co-receptors such as CD28 and CD154, leading to activation of T cells with proliferation [20] and proinflammatory cytokine production [18]. Second, because T cells express little TLR4, the principal pattern-recognition receptor that recognizes LPS, LPS was not considered to directly stimulate this cellular population. However, activation of naive human CD8+ T cells by TCR stimulation induced surface expression of TLR4 and CD14, which were then able to directly respond to LPS in a TLR4-dependent manner. This was specific to human but not murine CD8+ T cells [21]. Third, Th1 cell activation during active bacterial infection by microbe-associated molecular patterns, including LPS, does not require T-cell–intrinsic expression of TLR4 [22]. Fourth, directly relevant to the data presented here, an essential role for CD28 in LPS-induced T-cell activation and proliferation in vitro has been described [23–25]. Fifth, a critical role for CD28 in vivo was demonstrated in LPS-induced acute renal failure, using knockout mice [17]. Sixth, and significantly, CD28 was shown to act as an important mediator in some cases of gram-negative bacterial infections [26, 27]. Attenuation by AB103 peptide of CD28 signaling into the T cell thus can account for its ability to protect animals from gram-negative bacterial infection, as demonstrated here. Whether AB103 acts directly or indirectly on lymphocytes in response to LPS is now under study.

Our studies involving the CLP model suggest that survival of AB103-treated mice was, at least in part, due to the functional activities we examined. Treatment with AB103 increased the clearance of bacteria from peritoneum and blood and reduced tissue levels of bacteria in the liver, kidneys, and spleen (Figure 6). Further, mice treated with the peptide had a trend toward a decreased level of cytokine/chemokine expression (TNF-α, KC, and RANTES), compared with vehicle-treated controls. Reduced neutrophil recruitment in peptide-treated mice may have attenuated tissue injury. We previously reported that AB103 did not impair the mixed lymphocyte reaction in human cells [5].

In summary, the CD28 homodimer interface mimetic peptide AB103 does not target the pathogen but rather acts to modulate the host immune response, rendering its activity not pathogen specific. This peptide may therefore be used to treat infections from various sources having a substantial inflammatory component. Given its broad range of activity, AB103 merits further investigation as a potential adjunctive therapy for severe bacterial infections.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Barbara Boyd for assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant 2U54AI057168 to A. C. and R. K.) and Atox Bio (to S. O. and A. C.).

Potential conflicts of interest. A. S. and R. S. are employees of, R. K. is chief scientific officer of, and A. S. C. and S. M. O. have received funding from AtoxBio. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form of Disclosures of Potential Conflict of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:296–327. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000298158.12101.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annane D, Bellissant E, Bollaert PE, et al. Corticosteroids in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults: a systematic review. JAMA. 2009;301:2362–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arad G, Levy R, Nasie I, et al. Binding of superantigen toxins into the CD28 homodimer interface is essential for induction of cytokine genes that mediate lethal shock. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaempfer R, Arad G, Levy R, Hillman D, Nasie I, Rotfogel Z. CD28: direct and critical receptor for superantigen toxins. Toxins (Basel) 2013;5:1531–42. doi: 10.3390/toxins5091531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramachandran G, Tulapurkar ME, Harris KM, et al. A peptide antagonist of CD28 signaling attenuates toxic shock and necrotizing soft-tissue infection induced by Streptococcus pyogenes. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1869–77. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolan A, Weiden M, Kelly A, et al. CD40 and CD80/86 act synergistically to regulate inflammation and mortality in polymicrobial sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:301–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-515OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cross AS, Opal SM, Sadoff JC, Gemski P. Choice of bacteria in animal models of sepsis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2741–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2741-2747.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arad G, Levy R, Hillman D, Kaempfer R. Superantigen antagonist protects against lethal shock and defines a new domain for T-cell activation. Nat Med. 2000;6:414–21. doi: 10.1038/74672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Opal SM, Palardy JE, Chen WH, Parejo NA, Bhattacharjee AK, Cross AS. Active immunization with a detoxified endotoxin vaccine protects against lethal polymicrobial sepsis: its use with CpG adjuvant and potential mechanisms. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:2074–80. doi: 10.1086/498167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung CS, Chen Y, Grutkoski PS, Doughty L, Ayala A. SOCS-1 is a central mediator of steroid-increased thymocyte apoptosis and decreased survival following sepsis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1143–53. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung CS, Song GY, Lomas J, Simms HH, Chaudry IH, Ayala A. Inhibition of Fas/Fas ligand signaling improves septic survival: differential effects on macrophage apoptotic and functional capacity. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:344–51. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0102006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung CS, Venet F, Chen Y, et al. Deficiency of Bid protein reduces sepsis-induced apoptosis and inflammation, while improving septic survival. Shock. 2010;34:150–61. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181cf70fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang X, Venet F, Wang YL, et al. PD-1 expression by macrophages plays a pathologic role in altering microbial clearance and the innate inflammatory response to sepsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6303–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809422106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koike K, Moore EE, Moore FA, Read RA, Carl VS, Banerjee A. Gut ischemia/reperfusion produces lung injury independent of endotoxin. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:1438–44. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199409000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edgington ES. Randomization tests. 2nd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lydersen S, Fagerland MW, Laake P. Recommended tests for association in 2×2 tables. Stat Med. 2009;28:1159–75. doi: 10.1002/sim.3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singbartl K, Bockhorn SG, Zarbock A, Schmolke M, Van Aken H. T cells modulate neutrophil-dependent acute renal failure during endotoxemia: critical role for CD28. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:720–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004050381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suntharalingam G, Perry MR, Ward S, et al. Cytokine storm in a phase 1 trial of the anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody TGN1412. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1018–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arad G, Hillman D, Levy R, Kaempfer R. Broad-spectrum immunity against superantigens is elicited in mice protected from lethal shock by a superantigen antagonist peptide. Immunol Lett. 2004;91:141–5. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green JM, Thompson CB. Modulation of T cell proliferative response by accessory cell interactions. Immunol Res. 1994;13:234–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02935615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komai-Koma M, Gilchrist DS, Xu D. Direct recognition of LPS by human but not murine CD8(+) T cells via TLR4 complex. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1564–72. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Donnell H, Pham OH, Li LX, et al. Toll-like receptor and inflammasome signals converge to amplify the innate bactericidal capacity of T helper 1 cells. Immunity. 2014;40:213–24. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattern T, Flad HD, Brade L, Rietschel ET, Ulmer AJ. Stimulation of human T lymphocytes by LPS is MHC unrestricted, but strongly dependent on B7 interactions. J Immunol. 1998;160:3412–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ulmer AJ, Flad H, Rietschel T, Mattern T. Induction of proliferation and cytokine production in human T lymphocytes by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) Toxicology. 2000;152:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Berkel ME, Schrijver EH, van Mourik A, et al. A critical contribution of both CD28 and ICOS in the adjuvant activity of Neisseria meningitidis H44/76 LPS and lpxL1 LPS. Vaccine. 2007;25:4681–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hazlett LD, McClellan S, Barrett R, Rudner X. B7/CD28 costimulation is critical in susceptibility to Pseudomonas aeruginosa corneal infection: a comparative study using monoclonal antibody blockade and CD28-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:1292–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honstettre A, Meghari S, Nunes JA, et al. Role for the CD28 molecule in the control of Coxiella burnetii infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:1800–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1800-1808.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.