Abstract

Aims

We evaluated coronary artery disease (CAD) extent, severity, and major adverse cardiac events (MACEs) in never, past, and current smokers undergoing coronary CT angiography (CCTA).

Methods and results

We evaluated 9456 patients (57.1 ± 12.3 years, 55.5% male) without known CAD (1588 current smokers; 2183 past smokers who quit ≥3 months before CCTA; and 5685 never smokers). By risk-adjusted Cox proportional-hazards models, we related smoking status to MACE (all-cause death or non-fatal myocardial infarction). We further performed 1:1:1 propensity matching for 1000 in each group evaluate event risk among individuals with similar age, gender, CAD risk factors, and symptom presentation. During a mean follow-up of 2.8 ± 1.9 years, 297 MACE occurred. Compared with never smokers, current and past smokers had greater atherosclerotic burden including extent of plaque defined as segments with any plaque (2.1 ± 2.8 vs. 2.6 ± 3.2 vs. 3.1 ± 3.3, P < 0.0001) and prevalence of obstructive CAD [1-vessel disease (VD): 10.6% vs. 14.9% vs. 15.2%, P < 0.001; 2-VD: 4.4% vs. 6.1% vs. 6.2%, P = 0.001; 3-VD: 3.1% vs. 5.2% vs. 4.3%, P < 0.001]. Compared with never smokers, current smokers experienced higher MACE risk [hazard ratio (HR) 1.9, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.4–2.6, P < 0.001], while past smokers did not (HR 1.2, 95% CI 0.8–1.6, P = 0.35). Among matched individuals, current smokers had higher MACE risk (HR 2.6, 95% CI 1.6–4.2, P < 0.001), while past smokers did not (HR 1.3, 95% CI 0.7–2.4, P = 0.39). Similar findings were observed for risk of all-cause death.

Conclusion

Among patients without known CAD undergoing CCTA, current and past smokers had increased burden of atherosclerosis compared with never smokers; however, risk of MACE was heightened only in current smokers.

Keywords: Smoking risk, Coronary atherosclerosis, Coronary computed tomographic angiography, Major adverse cardiovascular risk

Clinical Perspective.

Although smoking is an established risk factor for major cardiac adverse events (MACE), the relative risk of current smoking vs. past smoking is less well studied. By using coronary CT angiography, our findings showed that when compared with never smokers, past smokers had increased plaque similar to current smokers; however, compared with never smokers, higher MACE risk was observed only in current smokers.

Introduction

Smoking is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease (CAD) and risk of future major adverse cardiac events (MACEs).1–6 While the increased in risk of events applies to current smokers, several previous studies have shown that individuals who have quit smoking have risk of future MACE that is similar to individuals who have never smoked.3,4 The underlying pathophysiology explaining why event rates do not remain elevated in individuals who have quit smoking is not well understood.

Coronary CT angiography (CCTA) has emerged as a non-invasive method to identify the presence, extent, severity, and type of coronary artery plaque.7–9 A large number of prognostic studies have shown that the degree of coronary atherosclerosis identified by CCTA is strongly predictive of subsequent cardiac events across a broad spectrum of clinical settings.7,8 To date, the relationship between smoking, CCTA findings, and subsequent MACE events has not been evaluated. The purpose of this study is to examine whether there is a difference in the presence, extent, severity of CAD as well as plaque type by CCTA to explore the relationships of these CAD measurements to the risk of future MACE and all-cause death in patients who never smoked, past, and current smokers.

Methods

Study population

We studied 9456 patients (mean age 57.1 ± 12.3 years, 55.5% male) without known CAD from patients enrolled in the CONFIRM (Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter) registry10 whose smoking status was known. Of the 27 125 patients in the CONFIRM registry, the following patients were sequentially excluded from this study: those lacking smoking status information (n = 11 289), known CAD [prior myocardial infarction (MI) and prior revascularization, n = 1665], and lacking MACE follow-up (n = 4714). Patients were referred by physicians to CCTA for clinical reasons, including both asymptomatic and symptomatic patients. Patients were classified as never smokers [5685 (60%)], past smokers—individuals who quit smoking ≥3 months prior to CCTA [2183 (23%)], and current smokers—individuals who currently smoked or quit <3 months prior CCTA [1588 (17%)] as previously described.7 Each participating institution obtained Institutional Review Board approval.

Pre-scan risk factor assessment

As previously described, clinical CAD risk factors including smoking history, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and family history were collected prior to the CCTA examination by direct patient interview by a physician or nurse research coordinator and/or by standardized site questionnaires.10 Chest symptom status at the time of CCTA was categorized as asymptomatic, non-cardiac, atypical, typical chest pain, and dyspnoea as previously described.11–13

Imaging analysis

Coronary CT angiography was performed in each institution using 64 slice or greater CT scanners.7,10 A modified 16-segment American Heart Association coronary tree model was used to detect plaques. Plaque composition (presence, severity stenosis, number, and characteristics) on CCTA was evaluated by experienced level III equivalent readers in accordance with SCCT guideline.14 Coronary plaque was identified any hyper- or hypodense structure distinct from the lumen and >1 mm2 in size. Coronary artery disease severity was classified for three groups: none (0% luminal stenosis), non-obstructive (1–49% luminal stenosis), and obstructive stenosis (≥50% luminal stenosis), which was sub-classified as 1-vessel disease (VD), 2-VD, and 3-VD (including left main disease). For measure of CAD extent, a segment involvement score (SIS) was defined as the total number of coronary artery segments with any plaque.8 The extent of CAD was classified for three groups: SIS with 0, 1–5 and >5 in accordance as previously described.8 Non-calcified plaque (NCP) [containing no calcification], partially calcified plaque (PCP) [containing both of calcification and NCP], or calcified plaque (CP) [containing only calcification] was recoded as plaque characteristics.

Patient follow-up

As reported previously,10 the primary outcomes were assessed at each institution by direct interview, telephone contact, review of medical records, or using a mailed standardized questionnaire. In the USA, all-cause mortality was additionally searched by the Social Security Death Index. Major adverse cardiac event was defined as all-cause death or non-fatal MI. Myocardial infarction was defined by site physicians in accordance with ACC/AHA guideline and the World Health Organization Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction.15,16

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± SD. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to conduct intergroup comparisons among never, past, and current smoker groups. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson χ2 tests. An one-way ANOVA or the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to conduct intergroup comparisons among never, past, and current smoking groups.

The relationship of smoking status to the endpoints of time to MACE or all-cause death was examined using risk-adjusted Cox proportional-hazards models, the latter adjusted for age, sex, all other CAD risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, family history of early CAD), all chest symptoms (non-anginal, atypical, typical chest pain, and dyspnoea), presence of obstructive CAD (≥50% stenosis), and SIS. Event rates were compared using the log-rank test. Also we generated MACE or all-cause-death-free survival curves among the never, past, and current smokers using Cox proportional-hazards models adjusting for the same variables within each stratum of smoking status. In addition, CAD stenosis severity (normal, non-obstructive, and obstructive CAD) and extent (SIS 0, 1–5, and >5) were assessed among never, past, and current smoking groups in relation to MACE by Cox proportional-hazards models adjusted for age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, family history, and all chest symptoms.

Because of the potential differences of age, gender, other risk factors, and symptom presentations among the three smoking groups, MACE and death risk were also analysed in subgroups of the three smoking categories matched for age, gender, the other CAD risk factors, and the chest symptoms using propensity scores, where the propensity score was the resulting probabilities of a logistic regression model predicting being among never, past, and current smoking groups with age, gender, other CAD risk factors, and the chest symptoms as predictors. The resulting propensity score was then applied 1:1:1 to match every never smoker to a corresponding past or current smoker using a Mahalanobis nearest-neighbour matching algorithm.17 This matching resulted in 1000 never smokers being matched to 1000 past or 1000 current smokers, respectively. Multivariable Cox proportional-hazards models were used to assess the relationship of smoking status to an endpoint of time to MACE or all-cause death after adjusting for age, gender, other CAD risk factors, chest symptoms, presence of obstructive CAD, and SIS.

Scaled Schoenfeld residuals were used to verify the assumption of proportional hazards of the Cox models.18 A hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated from the Cox models. All statistical calculations were carried out using STATA (Version 12, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) for Windows.

Results

Overall population

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics among never, past, and current smokers are shown in Table 1. There were multiple differences between the groups. Notably, compared with never smokers, past and current smokers were predominantly male and more commonly symptomatic. Never and past smokers were older than current smokers (57.4 ± 12.6 years vs. 59.3 ± 11.0 years vs. 53.0 ± 11.9 years, P < 0.0001). Past smokers had a greater prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia compared with never or current smokers. More current smokers had a family history of premature CAD and were male than the never and past smokers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study population among never, past, and current smokers (n = 9456)

| Never (n = 5685) | Past (n = 2183) | Current (n = 1588) | P-value for all | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 57.4 ± 12.6 | 59.3 ± 11.0† | 53.0 ± 11.9†,* | <0.0001 |

| Male gender | 2951 (51.9) | 1287 (59.0)† | 1006 (63.4)†,** | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 2629 (46.7) | 1116 (51.7)† | 721 (45.8)* | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 667 (11.8) | 297 (13.6)‡ | 160 (10.1)** | 0.004 |

| Dyslipidemia | 2853 (50.8) | 1262 (58.5)† | 823 (52.2)* | <0.001 |

| Family history | 2119 (38.3) | 808 (38.5) | 687 (44.8)†,* | <0.001 |

| Chest symptom | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 1812 (32.1) | 621 (28.8)‡ | 416 (26.7)†,* | <0.001 |

| Non-cardiac | 626 (11.1) | 242 (11.2) | 230 (14.8)†,** | <0.001 |

| Atypical | 2270 (40.3) | 768 (35.7)† | 657 (42.1)* | <0.001 |

| Typical | 518 (9.2) | 224 (10.4) | 154 (9.9) | 0.24 |

| Dyspnoea | 412 (7.3) | 299 (13.9)† | 102 (6.5)* | <0.001 |

Non-cardiac, atypical, and typical refer to chest pain types.

†P < 0.001 and ‡P < 0.05 for the comparison with never smoking group.

*P < 0.001 and **P < 0.05 for the comparison with past smoking group.

Coronary artery disease extent, severity, and plaque type

Coronary artery disease extent, severity, and plaque type are presented in Table 2. Regarding CAD extent as defined by SIS, compared with never smokers, past and current smokers had greater extent of coronary plaque, and past smokers had more plaque than current smokers. Regarding plaque severity, compared with never smokers, past and current smokers had a greater prevalence of obstructive CAD and the obstructive CAD categories including 1-, 2-, and 3-VD. Past smokers possessed more non-obstructive CAD compared with never and current smokers. The absence of plaque was most frequent in the never smokers. Non-calcified plaque and PCP were more prevalent among past and current smokers compared with never smokers.

Table 2.

Coronary artery plaque extent, severity, and characteristics among never, past, and current smokers (n = 9456)

| Never (n = 5685) | Past (n = 2183) | Current (n = 1588) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel disease (%) | ||||

| Normal | 2586 (45.49) | 671 (30.74)† | 625 (39.36)†,* | <0.001 |

| Non-obstructive disease | 2072 (36.45) | 952 (43.61)† | 548 (34.51)* | <0.001 |

| Obstructive disease | 1027 (18.07) | 560 (25.65)† | 415 (26.13)† | <0.001 |

| 1-vessel | 601 (10.57) | 331 (15.16)‡ | 236 (14.86)† | <0.001 |

| 2-vessel | 250 (4.40) | 136 (6.23)‡ | 97 (6.11)‡ | 0.001 |

| 3-vessel | 176 (3.10) | 93 (4.26)‡ | 82 (5.16)† | <0.001 |

| SIS (mean ± SD) | 2.1 ± 2.8 | 3.1 ± 3.3‡ | 2.6 ± 3.2‡,** | <0.0001 |

| SIS 1–5 | 2309 (40.62) | 1008 (46.17)† | 659 (41.50)* | <0.001 |

| SIS >5 | 790 (13.90)† | 504 (23.09)† | 304 (19.14)** | <0.001 |

| Prevalence of any plaque type (%) | ||||

| NCP | 975 (17.2) | 525 (24.1)† | 357 (22.5)† | <0.001 |

| PCP | 1185 (20.8) | 668 (30.6)† | 508 (32.0)† | <0.001 |

| CP | 1280 (22.5) | 663 (30.4)† | 388 (24.4)* | <0.001 |

SIS, segment involvement score; NCP, non-calcified plaque; PCP, partially calcified plaque; CP, calcified plaque.

†P < 0.001 and ‡P < 0.05 for the comparison with never smoking group.

*P < 0.001 and **P < 0.05 for the comparison with past smoking group.

Rates and adjusted risk of major adverse cardiac event and death by smoking categories

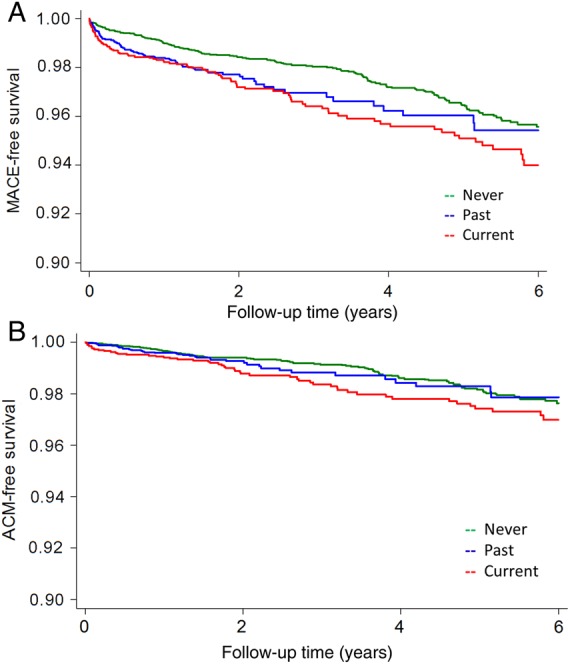

At a mean follow-up of 2.8 ± 1.9 years, 297 subjects experienced MACE (3.1%). Major adverse cardiac event occurred more often in current smokers compared with the past or never smokers (4.8% vs. 2.9% vs. 2.8%, P < 0.001 for all); however, the MACE rates were similar in the never and past smokers. With respect to all-cause death (192 patients), a higher proportion of current smokers died compared with past or never smokers (3.0% vs. 1.8% vs. 1.9%, P = 0.02 for all); however, the death rates were similar in never and past smokers (Table 3). In a multivariable Cox proportional-hazards model, adjusting for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, family history, all symptoms, coronary stenosis severity ≥50%, and SIS, current smokers experienced higher MACE risk compared with never smokers (HR 1.9, 95% CI 1.4–2.6, P < 0.001), while past smokers did not (HR 1.2, 95% CI 0.8–1.6, P = 0.35). Similarly, after adjustment for the same factors, the risk of death was higher in the current smokers (HR 2.0, 95% CI 1.4–2.9, P < 0.001) than in the never smokers, but not in the past smokers (HR 1.2, 95% CI 0.8–1.8, P = 0.31) (Table 3). Major adverse cardiac event or all-cause-death-free survival curves similarly showed increased risk of MACE or death only in current smokers (Figure 1A and B).

Table 3.

Rates and adjusted Cox proportional-hazard risk of major adverse cardiac event and all-cause death among whole population (n = 9456)

| Never (n = 5685) | Past (n = 2183) | Current (n = 1588) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rates of MACE and all-cause death (n, %) | ||||

| MACE | 158 (2.8) | 63 (2.9) | 76 (4.8)†,** | <0.001 |

| All-cause death | 106 (1.9) | 39 (1.8) | 47 (3.0)‡,** | 0.02 |

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||

| Adjusted risk of MACE and all-cause death | ||||

| MACE | 1.0 (reference) | 1.2 (0.8–1.6) | 1.9 (1.4–2.6)† | – |

| All-cause death | 1.0 (reference) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 2.0 (1.4–2.9)‡ | – |

MACE, major adverse cardiac event.

†P < 0.001 and ‡P < 0.05 for the comparison with never smoking group.

*P < 0.001 and **P < 0.05 for the comparison with past smoking group.

Figure 1.

(A) Risk-adjusted event-free survival curves for major adverse cardiac event among never, past, and current smokers (n = 9456). (B) Risk-adjusted event-free survival curves for all-cause death among never, past, and current smokers (n = 9456). Adjusted for age, gender, symptoms, dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, family history, all chest symptoms, segment involvement scores, and stenosis severity ≥50%. MACE, major adverse cardiac events.

Major adverse cardiac event risk assessed by smoking categories and coronary plaque extent and severity

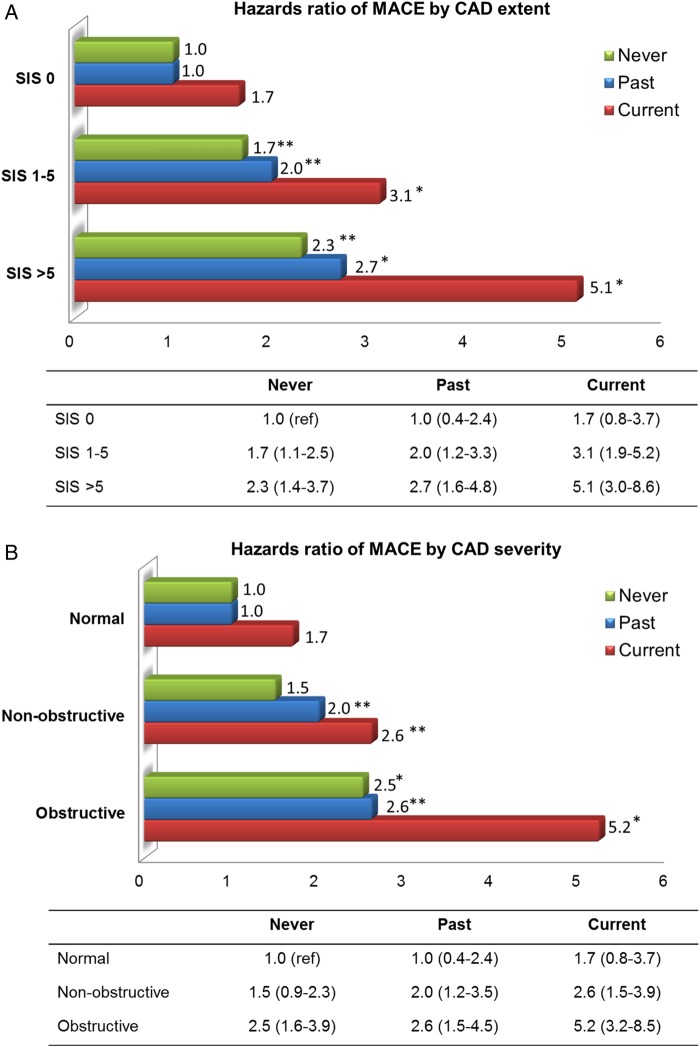

Figure 2A demonstrates results of risk-adjusted Cox proportional-hazards models for MACE by SIS category among never, past, and current smokers. Compared with the never smokers with SIS 0, past (HR 1.0, 95% CI 0.4–2.4, P = 0.996) or current smokers with SIS 0 (HR 1.7, 95% CI 0.8–2.4, P = 0.20) did not have increased MACE risk. In the SIS 1–5 category, the MACE risk was higher than that of the patients with SIS 0 in all smoking categories. While the risk among past smokers (HR 2.0, 95% CI 1.2–3.3, P = 0.01) was slightly higher than that of the never smokers (HR 1.7, 95% CI, 1.1–2.5, P = 0.02), it was much higher in the current smokers (HR 3.1, 95% CI, 1.9–5.2, P < 0.001). In the SIS >5 category, the MACE risk was further increased in all smoking categories. Of note, as with the SIS 1–5 category, the risk was slightly higher in the past smokers (HR 2.7, 95% CI 1.6–4.8, P < 0.001) than in the never smokers (HR 2.3, 95% CI 1.4–3.7, P = 0.001), but was much higher in the current smokers (HR 5.1, 95% CI 30–8.6, P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

(A) Risk-adjusted Cox proportional-hazards models for major adverse cardiac event by SIS 0, 1–5, and >5 among never, past, and current smokers (n = 9456). (B) Risk-adjusted Cox proportional-hazards models for major adverse cardiac event by normal, non-obstructive, and obstructive CAD among never, past, and current smokers (n = 9456). Adjusted for age, sex, symptoms, dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, family history, and all chest symptoms. MACE, major adverse cardiac events; SIS, segment involvement score; CAD, coronary artery disease. *P < 0.001 and **P < 0.05 for the comparison with never smokers with normal coronary CT angiography.

Figure 2B demonstrates results of risk-adjusted Cox proportional-hazards models for MACE by normal, non-obstructive, and obstructive CAD among never, past, and current smokers. The MACE risk among never smokers with non-obstructive CAD tended to be higher than that of those with normal CCTA (HR 1.5, 95% CI 0.9–2.3, P = 0.08). This risk was significantly higher in past smokers (HR 2.0, 95% CI 1.2–3.5, P = 0.008) and was even greater in current smokers (HR 2.6, 95% CI 1.5–4.6, P = 0.001). Subjects with obstructive CAD experienced higher MACE rates compared with never smokers with normal CCTA regardless of smoking status (never: HR 2.5, 95% CI 1.6–3.9, P < 0.001; past: HR 2.6, 95% CI 1.5–4.5, P = 0.001; current: HR 5.2, 95% CI 3.2–8.5, P < 0.001).

Matched population

Baseline characteristics

The matching was successful with no overall significant differences between the three groups in all variables for which the match was considered. Past smokers had more diabetes compared with never smokers (11.4% vs. 8.6%, P = 0.04) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Matched (1:1:1) population among never, past, and current smokers (n = 3000)

| Never (n = 1000) | Past (n = 1000) | Current (n = 1000) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 53.4 ± 11.6 | 54.1 ± 10.8 | 53.3 ± 12.0 | 0.28 |

| Male gender | 636 (63.6) | 620 (62.0) | 632 (63.2) | 0.74 |

| Hypertension | 446 (44.6) | 471 (47.1) | 453 (45.3) | 0.51 |

| Diabetes | 86 (8.6) | 114 (11.4)‡ | 105 (10.5) | 0.11 |

| Dyslipidemia | 516 (51.6) | 537 (53.7) | 529 (52.9) | 0.64 |

| Family history | 481 (48.1) | 455 (45.5) | 468 (46.8) | 0.51 |

| Chest symptom | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 261 (26.1) | 274 (27.4) | 267 (26.7) | 0.81 |

| Non-cardiac | 141 (14.1) | 142 (14.2) | 143 (14.3) | 0.99 |

| Atypical | 455 (45.5) | 420 (42.0) | 422 (42.2) | 0.21 |

| Typical | 95 (9.5) | 112 (11.2) | 108 (10.8) | 0.43 |

| Dyspnoea | 48 (4.8) | 52 (5.2) | 60 (6.0) | 0.48 |

Non-cardiac, atypical, and typical refer to chest pain types.

†P < 0.001 and ‡P < 0.05 for the comparison with never smoking group.

*P < 0.001 and **P < 0.05 for the comparison with past smoking group.

Coronary artery disease extent, severity, and plaque type

Both current and past smokers had higher SIS and greater prevalence of all plaque types, compared with never smokers (Table 5). Past smokers more commonly had non-obstructive CAD, and current smokers had a greater prevalence of obstructive CAD, compared with never smokers. Current smokers had a higher prevalence of PCP compared with past and never smokers.

Table 5.

Coronary artery plaque extent, severity, and characteristics among matched never, past, and current smokers (n = 3000)

| Never (n = 1000) | Past (n = 1000) | Current (n = 1000) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel disease (%) | ||||

| Normal | 472 (47.2) | 397 (39.7)‡ | 387 (38.7)† | <0.001 |

| Non-obstructive disease | 338 (33.8) | 389 (38.9)‡ | 341 (34.1)** | 0.03 |

| Obstructive disease | 190 (19.0) | 214 (21.4) | 272 (27.2)†,** | <0.001 |

| 1-vessel | 101 (10.1) | 132 (13.2)‡ | 155 (15.5)† | 0.001 |

| 2-vessel | 50 (5.0) | 51 (5.1) | 63 (6.3) | 0.36 |

| 3-vessel | 39 (3.9) | 31 (3.1) | 54 (5.4)** | 0.03 |

| SIS (mean ± SD) | 2.0 ± 2.8 | 2.5 ± 3.1† | 2.6 ± 3.1† | <0.0001 |

| SIS 1–5 | 398 (39.8) | 425 (42.5) | 425 (42.5) | 0.37 |

| SIS >5 | 130 (13.0) | 178 (17.8)‡ | 188 (18.8)† | 0.001 |

| Prevalence of any plaque type (%) | ||||

| NCP | 176 (17.6) | 233 (23.3)‡ | 231 (23.1)‡ | 0.002 |

| PCP | 195 (19.5) | 274 (27.4)† | 335 (33.5)†,** | <0.001 |

| CP | 193 (19.3) | 250 (25.0)‡ | 258 (25.8)‡ | 0.001 |

SIS, segment involvement score; NCP, non-calcified plaque; PCP, partially calcified plaque; CP, calcified plaque.

†P < 0.001 and ‡P < 0.05 for the comparison with never smoking group.

*P < 0.001 and **P < 0.05 for the comparison with past smoking group.

Rates and adjusted risk of major adverse cardiac event and death

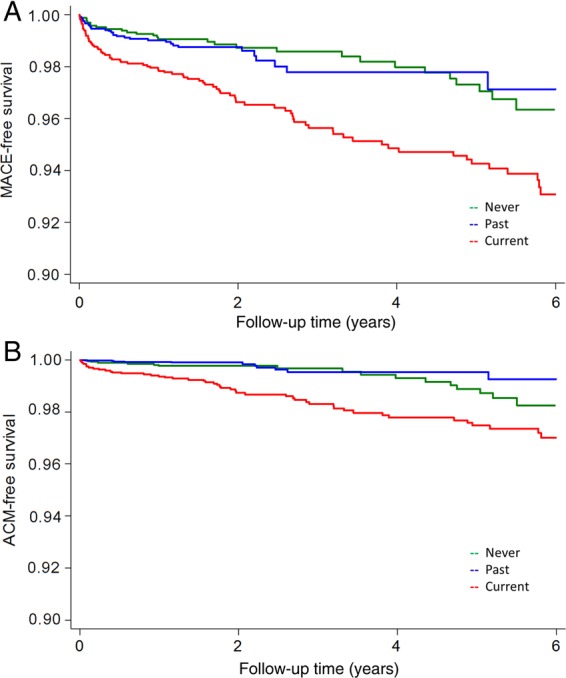

A higher proportion of current smokers experienced MACE (6.9%, P < 0.001 vs. both other groups); however, MACE occurred in a similar proportion of the past smokers and the never smokers (2.4% vs. 2.2%, P = 0.77). Current smokers had a higher rate of death than the other two groups (4.2%, P < 0.001 vs. both other groups); however, the death rate was not different between the past and never smokers (1.1% vs. 1.4%, P = 0.55) (Table 6). In multivariable Cox proportional analysis, adjusting for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, family history, all symptoms, coronary stenosis severity ≥50%, and SIS, current smokers experienced a higher risk of MACE compared with never smokers (HR 2.6, 95% CI 1.6–4.2, P < 0.001), but past smokers did not (HR 1.3, 95% CI 0.7–2.4, P = 0.39). Similarly, after adjustment for the same factors, the risk of death was higher in current smokers (HR 2.5, 95% CI 1.3–4.6, P = 0.005), compared with the never smokers, while it was not higher in the past smokers (HR 1.1, 95% CI 0.5–2.6, P = 0.75) (Table 6). Major adverse cardiac event or all-cause-death-free survival curves showed increased risk of MACE or death only in current smokers (Figure 3A and B).

Table 6.

Rates and adjusted Cox proportional-hazard risk of major adverse cardiac event and all-cause death among whole population (n = 3000)

| Never (n = 1000) | Past (n = 1000) | Current (n = 1000) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rates of MACE and all-cause death (n, %) | ||||

| MACE | 22 (2.2) | 24 (2.4) | 69 (6.9)†,* | <0.001 |

| All-cause death | 14 (1.4) | 11 (1.1) | 42 (4.2)†,* | <0.001 |

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||

| Adjusted risk of MACE and all-cause death | ||||

| MACE | 1.0 (reference) | 1.3 (0.7–2.4) | 2.6 (1.6–4.2)† | – |

| All-cause death | 1.0 (reference) | 1.1 (0.5–2.6) | 2.5 (1.3–4.6)‡ | – |

MACE, major adverse cardiac event.

†P < 0.001 and ‡P < 0.05 for the comparison with never smoking group.

*P < 0.001 and **P < 0.05 for the comparison with past smoking group.

Figure 3.

(A) Risk-adjusted event-free survival curves for major adverse cardiac event among matched never, past, and current smokers (n = 3000). (B) Risk-adjusted event-free survival curves for all-cause death among matched never, past, and current smokers (n = 3000). Adjusted for age, gender, symptoms, dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, family history, all chest symptoms, segment involvement scores, and stenosis severity ≥50%. Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Discussion

This report from the CONFIRM registry is the first study to examine the relationship between the extent and severity of CAD by coronary CT angiography, smoking status, and the risk of subsequent MACE events. We demonstrated that past and current smokers had similar extent and severity of coronary atherosclerosis, which was greater than that of never smokers; however, only current smokers had greater risk-adjusted cardiac events. We observed similar findings with respect to the extent and severity of CAD and cardiac events in a subgroup that was propensity matched to achieve similarities of age, gender, other CAD risk factors, and chest symptoms. In the matched population, compared with never smokers, both past and current smokers had a higher prevalence of non-obstructive or obstructive CAD and greater extent of CAD; however, only current smokers experienced a significantly higher MACE risk. This risk among past smokers was slightly but not significantly higher than that of never smokers.

Numerous prior investigators have observed that smoking was associated with the atherosclerosis formation, progression, and future MACE risk.1–6,19–21 Active smoking is strongly associated with endothelial dysfunction and coronary thrombosis.19,22–29 In current smokers, the impaired release of tissue plasminogen activator antigen and reduced coronary blood flow has been reported compared with non-smokers.19,22 Further, platelet aggregation is increased among active smokers.24–27 These factors, along with the increased amounts of coronary atherosclerosis, may be responsible for the reported increase in risk of acute coronary thrombosis22,24–27 and potentially contribute to the association of current smokers with higher MACE risk noted in the present study.

Our finding that future MACE risk was similar among never and past smokers is concordant with numerous prior studies.3,4 Regarding the angiographic correlates of these observations, previous studies using invasive coronary angiography have assessed the relationship of the extent CAD and MACE risk according to smoking status.5,6 As was found in the present study, these prior reports showed that smoking cessation was associated with reduced risk of death, MI, or revascularization regardless of the angiographic extent of CAD.

The potential mechanism of the similar risks of events in past and never smokers despite the increased burden of atherosclerosis is unclear. It may be due to improvement of endothelial function,28,29 decreased fibrinogen and inflammatory markers30 that have been associated with smoking cessation, or some other biologic protective effect reducing the risk of coronary artery plaque rupture. As another potential contributing factor, smokers who successfully quit may also have adopted other heart-healthy lifestyle behaviours such as diet, exercise, and the use of medications that reduce risk of coronary artery event to a greater degree than the never smokers.

Large observational studies have demonstrated that the age of patients who stopped smoking was an important factor in explaining known decrease in mortality risk associated with smoking cessation.31,32 In a study of 34 439 men followed up to 50 years,31 patients who quit smoking before 30 years of age avoided most all of mortality risk, whereas reduction in mortality risk associated with smoking cessation decreased progressively as the age at time of quitting increased. Similarly, a study of 1.2 million women resurveyed 3–8 years after initial recording of smoking status,32 demonstrated that cessation of smoking before age 30 avoided almost all of the excess mortality caused by smoking, and that the mortality benefit of quitting smoking compared with not quitting decreased progressively as the age at the time of smoking cessation increased. Other studies have also demonstrated that there is decreased incidence of coronary artery calcification as a marker of atherosclerosis in past smokers compared with current smokers and that the degree of this decreased incidence is age related.33,34 In our study, the risk of MACE events in the past smokers appeared to improve over time in our unmatched population. The results in our matched population, however, suggest that the risk of MACE events is similar between past and never smokers early after testing. Whether the difference in our matched and unmatched populations in this regard is related to increased risk factor burden in the past smokers of the unmatched population compared with the never smokers or to other factors cannot be determined from our data. We did not have information regarding the age at which smoking was stopped in the past smokers of this study.

The study has several limitations. The study includes patients undergoing clinical indicated CCTA studies and whether the present results can be extrapolated to population-based cohorts remains unknown. The follow-up period was for an average of 2.8 years. The hazard ratio for MACE was slightly but not significantly higher in past smokers than in never smokers (1.2 and 1.3 in the whole and the matched populations, respectively). A longer follow-up with more clinical events is needed to determine whether there is a difference in the event rates in these two groups. From the CONFIRM registry, only patients in whom smoking status was reported and follow-up for MACE was available were included. Smoking information was limited to identification of patients who were current, past, or never smokers. There was no information regarding duration and amount of smoking, time interval from smoking cessation to testing, or exposure to passive smoking, all of which are associated with CAD and the future risk.21,31,32,35,36 There was no information regarding lifestyle behaviour in the various groups.

Conclusion

Among patients without known CAD undergoing CCTA, current and past smokers had increased burden of atherosclerosis compared with never smokers; however, the risk of death and MACE was heightened only in the current smokers.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (1R01HL115150). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research was supported by Leading Foreign Research Institute Recruitment Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (MSIP) (2012027176). This study was also funded, in part, by a generous gift from the Dalio Institute of Cardiovascular Imaging and the Michael Wolk Foundation.

Conflict of interest: S.A. received support from Siemens and Bayer Schering Pharma and has consulted for Servier. D.A. has served on the Speakers' Bureau of GE Healthcare. M.J.B. has consulted for GE Healthcare. F.C. received grant support from GE Healthcare and has served on the Speakers' Bureau of Bracco, and has consulted for Servier. K.C. received grant support from Bayer Pharma. B.J.W.C. received research and fellowship support from GE Healthcare, research support from Servier, and educational support from TeraRecon. R.C. has served as a consultant for Astellas Pharma, GE Healthcare, and Novartis. J.H. received a research grant from Siemens Medical Systems. P.A.K. received research support from GE Healthcare. J.L. received research support from GE Healthcare and speakers' bureau. G.P. received grant support from GE Healthcare and Heartflow. G.R. received grant support from Siemens and Bayer Pharma. A.D. was partially supported by Clinical Translational Science Center (grant UL1-RR024996). All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- 1.McEvoy JW, Blaha MJ, Rivera JJ, Budoff MJ, Khan AN, Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Raggi P, Min JK, Rumberger JA, Callister TQ, Blumenthal RS, Nasir K. Mortality rates in smokers and nonsmokers in the presence or absence of coronary artery calcification. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5:1037–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw LJ, Raggi P, Callister TQ, Berman DS. Prognostic value of coronary artery calcium screening in asymptomatic smokers and non-smokers. Eur Heart J 2006;27:968–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musallam KM, Rosendaal FR, Zaatari G, Soweid A, Hoballah JJ, Sfeir PM, Zeineldine S, Tamim HM, Richards T, Spahn DR, Lotta LA, Peyvandi F, Jamali FR. Smoking and the risk of mortality and vascular and respiratory events in patients undergoing major surgery. JAMA Surg 2013;148:755–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suskin N, Sheth T, Negassa A, Yusuf S. Relationship of current and past smoking to mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:1677–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasdai D, Garratt KN, Grill DE, Lerman A, Holmes DR. Effect of smoking status on the long-term outcome after successful percutaneous coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med 1997;336:755–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vlietstra RE, Kronmal RA, Oberman A, Frye RL, Killip T. Effect of cigarette smoking on survival of patients with angiographically documented coronary artery disease. Report from the cass registry. JAMA 1986;255:1023–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Min JK, Dunning A, Lin FY, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Callister TQ, Chang HJ, Cheng V, Chinnaiyan K, Chow BJ, Delago A, Hadamitzky M, Hausleiter J, Kaufmann P, Maffei E, Raff G, Shaw LJ, Villines T, Berman DS, CONFIRM Investigators. Age- and sex-related differences in all-cause mortality risk based on coronary computed tomography angiography findings results from the international multicenter confirm (coronary CT angiography evaluation for clinical outcomes: an international multicenter registry) of 23,854 patients without known coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:849–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Min JK, Shaw LJ, Devereux RB, Okin PM, Weinsaft JW, Russo DJ, Lippolis NJ, Berman DS, Callister TQ. Prognostic value of multidetector coronary computed tomographic angiography for prediction of all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:1161–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Werkhoven JM, Schuijf JD, Gaemperli O, Jukema JW, Boersma E, Wijns W, Stolzmann P, Alkadhi H, Valenta I, Stokkel MP, Kroft LJ, de Roos A, Pundziute G, Scholte A, van der Wall EE, Kaufmann PA, Bax JJ. Prognostic value of multislice computed tomography and gated single-photon emission computed tomography in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:623–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Min JK, Dunning A, Lin FY, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah MH, Berman DS, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Callister TQ, Chang HJ, Cheng V, Chinnaiyan KM, Chow B, Delago A, Hadamitzky M, Hausleiter J, Karlsberg RP, Kaufmann P, Maffei E, Nasir K, Pencina MJ, Raff GL, Shaw LJ, Villines TC. Rationale and design of the CONFIRM (coronary CT angiography evaluation for clinical outcomes: an international multicenter) registry. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2011;5:84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diamond GA, Forrester JS. Analysis of probability as an aid in the clinical diagnosis of coronary-artery disease. N Engl J Med 1979;300:1350–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abidov A, Rozanski A, Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Aboul-Enein F, Cohen I, Friedman JD, Germano G, Berman DS. Prognostic significance of dyspnea in patients referred for cardiac stress testing. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1889–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng VY, Berman DS, Rozanski A, Dunning AM, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Callister TQ, Chang HJ, Chinnaiyan K, Chow BJ, Delago A, Gomez M, Hadamitzky M, Hausleiter J, Karlsberg RP, Kaufmann P, Lin FY, Maffei E, Raff GL, Villines TC, Shaw LJ, Min JK. Performance of the traditional age, sex, and angina typicality-based approach for estimating pretest probability of angiographically significant coronary artery disease in patients undergoing coronary computed tomographic angiography: results from the multinational coronary CT angiography evaluation for clinical outcomes: an international multicenter registry (CONFIRM). Circulation 2011;124:2423–2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbara S, Arbab-Zadeh A, Callister TQ, Desai MY, Mamuya W, Thomson L, Weigold WG. Scct guidelines for performance of coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the society of cardiovascular computed tomography guidelines committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2009;3:190–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE, Jr, Chavey WE, 2nd, Fesmire FM, Hochman JS, Levin TN, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Wright RS, Smith SC, Jr, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Halperin JL, Hunt SA, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lytle BW, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction); American College of Emergency Physicians; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons; American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-Elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:e1–e157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:2173–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imbens G. The role of propensity score in estimating dose-response functions. Biometrika 2000;87: 706–710. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994;81:515–52620. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newby DE, McLeod AL, Uren NG, Flint L, Ludlam CA, Webb DJ, Fox KA, Boon NA. Impaired coronary tissue plasminogen activator release is associated with coronary atherosclerosis and cigarette smoking: direct link between endothelial dysfunction and atherothrombosis. Circulation 2001;103:1936–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howard G, Wagenknecht LE, Burke GL, Diez-Roux A, Evans GW, McGovern P, Nieto FJ, Tell GS. Cigarette smoking and progression of atherosclerosis: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. JAMA 1998;279:119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, Rostron B, Thun M, Anderson RN, McAfee T, Peto R. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the united states. N Engl J Med 2013;368:341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newby DE, Wright RA, Labinjoh C, Ludlam CA, Fox KA, Boon NA, Webb DJ. Endothelial dysfunction, impaired endogenous fibrinolysis, and cigarette smoking: a mechanism for arterial thrombosis and myocardial infarction. Circulation 1999;99:1411–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otsuka R, Watanabe H, Hirata K, Tokai K, Muro T, Yoshiyama M, Takeuchi K, Yoshikawa J. Acute effects of passive smoking on the coronary circulation in healthy young adults. JAMA 2001;286:436–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis JW, Hartman CR, Lewis HD, Shelton L, Eigenberg DA, Hassanein KM, Hignite CE, Ruttinger HA. Cigarette smoking-induced enhancement of platelet function: lack of prevention by aspirin in men with coronary artery disease. J Lab Clin Med 1985;105:479–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis JW, Shelton L, Eigenberg DA, Hignite CE, Watanabe IS. Effects of tobacco and non-tobacco cigarette smoking on endothelium and platelets. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1985;37:529–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis JW, Shelton L, Hartman CR, Eigenberg DA, Ruttinger HA. Smoking-induced changes in endothelium and platelets are not affected by hydroxyethylrutosides. Br J Exp Pathol 1986;67:765–771. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis JW, Shelton L, Eigenberg DA, Hignite CE. Lack of effect of aspirin on cigarette smoke-induced increase in circulating endothelial cells. Haemostasis 1987;17:66–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson HM, Gossett LK, Piper ME, Aeschlimann SE, Korcarz CE, Baker TB, Fiore MC, Stein JH. Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on endothelial function: 1-year outcomes from a randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1988–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugiura T, Dohi Y, Hirowatari Y, Yamashita S, Ohte N, Kimura G, Fujii S. Cigarette smoking induces vascular damage and persistent elevation of plasma serotonin unresponsive to 8 weeks of smoking cessation. Int J Cardiol 2013;166:748–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bakhru A, Erlinger TP. Smoking cessation and cardiovascular disease risk factors: results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. PLoS Med 2005;2:e160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet 2013;381:133–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ 2004;328:1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jöckel KH, Lehmann N, Jaeger BR, Moebus S, Möhlenkamp S, Schmermund A, Dragano N, Stang A, Grönemeyer D, Seibel R, Mann K, Volbracht L, Siegrist J, Erbel R. Smoking cessation and subclinical atherosclerosis—results from the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. Atherosclerosis 2009;203:221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehmann N, Möhlenkamp S, Mahabadi AA, Schmermund A, Roggenbuck U, Seibel R, Grönemeyer D, Budde T, Dragano N, Stang A, Mann K, Moebus S, Erbel R, Jöckel KH. Effect of smoking and other traditional risk factors on the onset of coronary artery calcification: results of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. Atherosclerosis 2014;232:339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yankelevitz DF, Henschke CI, Yip R, Boffetta P, Shemesh J, Cham MD, Narula J, Hecht HS, FAMRI-IELCAP Investigators. Second-hand tobacco smoke in never smokers is a significant risk factor for coronary artery calcification. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:651–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Auerbach O, Carter HW, Garfinkel L, Hammond EC. Cigarette smoking and coronary artery disease: a macroscopic and microscopic study. Chest 1976;70:697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]