Abstract

Statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS) are one of the principal reasons for statin non-adherence and/or discontinuation, contributing to adverse cardiovascular outcomes. This European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) Consensus Panel overviews current understanding of the pathophysiology of statin-associated myopathy, and provides guidance for diagnosis and management of SAMS. Statin-associated myopathy, with significant elevation of serum creatine kinase (CK), is a rare but serious side effect of statins, affecting 1 per 1000 to 1 per 10 000 people on standard statin doses. Statin-associated muscle symptoms cover a broader range of clinical presentations, usually with normal or minimally elevated CK levels, with a prevalence of 7–29% in registries and observational studies. Preclinical studies show that statins decrease mitochondrial function, attenuate energy production, and alter muscle protein degradation, thereby providing a potential link between statins and muscle symptoms; controlled mechanistic and genetic studies in humans are necessary to further understanding. The Panel proposes to identify SAMS by symptoms typical of statin myalgia (i.e. muscle pain or aching) and their temporal association with discontinuation and response to repetitive statin re-challenge. In people with SAMS, the Panel recommends the use of a maximally tolerated statin dose combined with non-statin lipid-lowering therapies to attain recommended low-density lipoprotein cholesterol targets. The Panel recommends a structured work-up to identify individuals with clinically relevant SAMS generally to at least three different statins, so that they can be offered therapeutic regimens to satisfactorily address their cardiovascular risk. Further research into the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms may offer future therapeutic potential.

Keywords: Statin, Muscle symptoms, Myalgia, Myopathy, Statin intolerance, Mitochondrial, Consensus statement, Lipids, Cholesterol

Introduction

Statin therapy is the cornerstone for prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease (CVD), and is generally safe and well tolerated.1 In randomized, controlled trials (RCTs), adverse event rates (including complaints of muscle pain) are similar in statin and placebo groups,2–4 and compare favourably with event rates for other agents commonly used in CVD prevention, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors5 and beta-blockers.6 However, statins do cause a rare side-effect known as myositis, defined as muscle symptoms in association with a substantially elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) concentration. Creatine kinase is the enzyme released from damaged muscle cells, and CK elevations >10× the upper limit of normal (ULN) occur in 1 per 1000 to 1 per 10 000 people per year,7 depending on the statin, its dose, and the presence of other risk factors. Over the last decade, a series of observational studies have attributed a number of other adverse effects to statins, including musculoskeletal complaints, gastro-intestinal discomfort, fatigue, liver enzyme elevation, peripheral neuropathy, insomnia, and neurocognitive symptoms. In addition, randomized trials have shown a small increase in the risk of incident diabetes.8–10 Muscle symptoms, the most prevalent of these effects, are the focus of this review.

In contrast to RCTs, patient registries, together with clinical experience, indicate that 7–29% of patients complain of statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS).11–15 These are usually associated with normal or slightly elevated CK concentrations. Statin-associated muscle symptoms likely contribute significantly to the very high discontinuation rates of statin therapy (up to 75%) within 2 years of initiation.16 Indeed, in 65% of former statin users, the main reason for statin non-adherence or discontinuation was the onset of side effects, predominantly muscle-related effects.13 Such non-adherence/discontinuation from treatment may have a marked impact on CVD benefit, as suggested by the higher mortality in elderly secondary prevention patients with low vs. high adherence to statin therapy (24% vs. 16%, respectively; adjusted hazard ratio, 1.25; P = 0.001).17 Similarly, a meta-analysis showed a 15% lower CVD risk in patients who were adherent to statins compared with those with low adherence.18

The clinical presentation of muscle symptoms is highly heterogeneous, as reflected by the variety of definitions in the literature (see Supplementary material online, Table S1). Muscle pain or aching, stiffness, tenderness or cramp (often referred to as ‘myalgia’19) attributed by patients to their statin use is usually symmetrical but may be localized, and can be accompanied by muscle weakness; any of these effects occur predominantly without an elevation of CK.

As indicated above, reported rates of muscle symptoms are invariably lower in blinded RCTs when compared with those in registries and observational studies, with myalgia rates similar in subjects on statin or placebo.2–4,20,21 Admittedly, patients with comorbidities that would predispose to an increased risk for musculoskeletal symptoms may have been underrepresented in RCTs. In addition, dedicated questionnaires into muscle complaints are not always incorporated within trial methodology. Conversely, the lack of a placebo comparator in observational studies precludes the ability to establish a causal relationship between statin and muscle complaints. The Effects of Statins on Muscle Performance (STOMP) study is, to our knowledge, the only randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study specifically designed to examine the effect of statins on skeletal muscle symptoms and performance.22 Among the 420 statin-naïve subjects randomized to atorvastatin 80 mg daily or placebo for 6 months, 9.4% of the statin-treated and 4.6% of control subjects met the study definition of myalgia (P = 0.054), suggesting that the incidence of muscle complaints due to the statin is considerably less than that reported in observational trials. The STOMP study also found no differences in the measures of muscle strength or exercise performance between statin-treated and placebo subjects. Few other RCTs have queried for muscle complaints among participants.20 Muscle complaints in other clinical trials have been similar in statin-treated and placebo subjects.4,20,23,24 However, even a small increase in myalgia rates would still represent a substantial number of patients given the widespread use of statins.

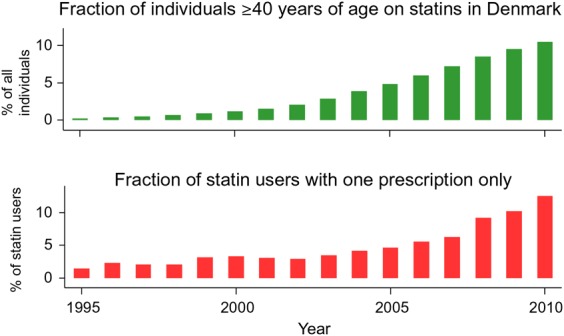

From a treatment viewpoint, Zhang et al.14 showed that 90% of patients reporting SAMS to one statin were able to tolerate an alternative statin with continued use after 12 months, suggesting that statin-attributed symptoms may have had other causes or were not generalizable to other statins. Similar results were reported by Mampuya et al.25 Furthermore, increased prescription of statins itself appears to be associated with increased non-adherence or discontinuation, as illustrated for Denmark over the period 1995–2010 (Figure 1).26,27 Different factors may have contributed to this finding. Increased media coverage of statins and their perceived side-effects, as well as wider prescription in primary prevention where the benefits may be less obvious to patients, may be contributing to greater non-adherence and discontinuation.

Figure 1.

Trends in statin use (upper panel) and statin non-adherence/discontinuation (lower panel) in adults ≥40 years, in Denmark over the period 1995–2010. Statin use from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2010 was classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Classification of Drugs code C10AA, as registered in the national Danish Registry of Medicinal Products Statistics, recording information on all prescribed drugs dispensed at all Danish pharmacies from 1995 onwards (for details see references26,27). The percentage of the Danish population aged ≥40 years on statins increased from <1% in 1995 to 11% in 2010. Correspondingly, non-adherence or discontinuation (defined as the percentage of patients starting statins who only redeemed one prescription) increased from 2% in 1995 to 13% in 2010. Figure designed by Dr Sune F. Nielsen and Prof Børge G. Nordestgaard.

Here, this European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) Consensus Panel provides an overview of the science underlying the pathophysiology of statin-induced myopathy, as well as guidance for clinicians on the diagnosis and management of SAMS. We have avoided the use of the term ‘statin intolerance’, as this is not specific for muscle symptoms. These recommendations can assist in improving the likelihood that patients experiencing SAMS receive optimal low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) lowering therapy to minimize their risk for CVD.

Assessment and diagnosis of statin-associated muscle symptoms

While consensus groups including the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology28 and the National Lipid Association19 have presented definitions of SAMS based on symptoms and the magnitude of CK elevation, less attention has been paid to clinical diagnostic criteria. Indeed, a definitive diagnosis of SAMS is difficult because symptoms are subjective and there is no ‘gold standard’ diagnostic test. Importantly, there is also no validated muscle symptom questionnaire, although the National Lipid Association has proposed a symptom scoring system based on the STOMP trial and the PRIMO survey (see Supplementary material online, Table S2).19 Consequently, we suggest that assessment of the probability of SAMS being due to a statin take account of the nature of the muscle symptoms, the elevation in CK levels and their temporal association with statin initiation, discontinuation, and re-challenge. Note that this is a clinical definition, which may not be appropriate for regulatory purposes.

In the absence of a standardized classification of SAMS, we propose to integrate all muscle-related complaints (e.g. pain, weakness, or cramps) as ‘muscle symptoms’, subdivided by the presence or absence of CK elevation (Table 1). Pain and weakness in typical SAMS are usually symmetrical and proximal, and generally affect large muscle groups including the thighs, buttocks, calves, and back muscles. Discomfort and weakness typically occur early (within 4–6 weeks after starting statin therapy22), but may still occur after many years of treatment. Onset of new symptoms may occur with an increase in statin dose or initiation of an interacting drug. The symptoms appear to be more frequent in physically active individuals.11 Statin-associated muscle symptoms often appear more promptly when patients are re-exposed to the same statin.

Table 1.

Definitions of statin-associated muscle symptoms proposed by the EAS Consensus Panel

| Symptoms | Biomarker | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Muscle symptoms | Normal CK | Often called ‘myalgia’. May be related to statin therapy. Causality is uncertain in view of the lack of evidence of an excess of muscle symptoms in blinded randomized trials comparing statin with placebo. |

| Muscle symptoms | CK >ULN <4× ULN | Minor elevations of CK in the context of muscle symptoms are commonly due to increased exercise or physical activity, but also may be statin-related; this may indicate an increased risk for more severe, underlying muscle problems.19 |

| CK >4 <10× ULN | ||

| Muscle symptoms | CK >10× ULN | Often called myositis or ‘myopathy’ by regulatory agencies and other groups (even in the absence of a muscle biopsy or clinically demonstrated muscle weakness). Blinded trials of statin vs. placebo show an excess with usual statin doses of about 1 per 10 000 per year.4 Pain is typically generalized and proximal and there may be muscle tenderness and weakness. May be associated with underlying muscle disease. |

| Muscle symptoms | CK >40× ULN | Also referred to as rhabdomyolysis when associated with renal impairment and/or myoglobinuria. |

| None | CK >ULN <4× ULN | Raised CK found incidentally, may be related to statin therapy. Consider checking thyroid function or may be exercise-related. |

| None | CK >4× ULN | Small excess of asymptomatic rises in CK have been observed in randomized blinded trials in which CK has been measured regularly. Needs repeating but if persistent, then clinical significance is unclear. |

CK, creatine kinase; ULN, upper limit of the normal range.

In the vast majority of cases, SAMS are not accompanied by marked CK elevation.24,29 For SAMS with CK elevations >10× ULN, usually referred to as myopathy, the incidence is approximately 1 per 10 000 per year with a standard statin dose (e.g. simvastatin 40 mg daily). The risk varies, however, among different statins, and increases not only with the dose of statin, but also with factors associated with increased statin blood concentrations (e.g. genetic factors, ethnicity, interacting drugs, and patient characteristics) (see Box 1).30 Rhabdomyolysis is a severe form of muscle damage associated with very high CK levels with myoglobinaemia and/or myoglobinuria with a concomitantly increased risk of renal failure. The incidence of rhabdomyolysis in association with statin therapy is ∼1 in 100 000 per year.7 In view of the rarity of CK elevations during statin therapy, it is not recommended to routinely monitor CK. Even if an asymptomatic elevation of CK is detected, the clinical significance is unclear.

Box 1. Risk factors for statin-associated muscle symptoms. Adapted from Mancini et al.9.

| Anthropometric |

|

| Concurrent conditions |

|

| Surgery |

|

| Related history |

|

| Genetics |

|

| Other risk factors |

|

Statin-associated muscle symptoms are more likely to be caused by statins when elevated CK levels decrease after cessation of either the statin or the interacting drug, or when symptoms regress markedly within a few weeks of cessation of the statin and/or reappear within a month of drug re-challenge. Time to reappearance of symptoms is also influenced by the dose of statin and the duration of the re-challenge. Individual patient drug–placebo clinical trials have been suggested as an approach to confirming diagnosis of SAMS,31 but are not feasible in the routine outpatient setting.

Management of statin-associated muscle symptoms

If a patient complains of muscle symptoms, the clinician needs to evaluate risk factors which can predispose to statin-associated myopathy, exclude secondary causes (especially hypothyroidism and other common myopathies such as polymyalgia rheumatica, or increased physical activity), and review the indication for statin use. The clinician should bear in mind that other commonly prescribed drugs such as anti-inflammatory (glucocorticoids), antipsychotic (risperidone, haloperidol), immunosuppressant or antiviral agents (human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors), lipid-modifying drugs (gemfibrozil), as well as substances of abuse (alcohol, opioids, and cocaine) may also cause muscle-related side effects. Several factors including female sex, ethnicity, multisystem disease, and small body frame predispose to SAMS (see Box 1), with the presence of an increasing number of factors associated with greater risk.9,30,32–34 Additionally, pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions (DDIs) that increase statin exposure increase the risk of statin-associated myopathy (Box 2). Concomitant treatment with a statin and medication(s) that inhibit cytochrome P450 (CYP450) isoenzymes, organic anion transport protein 1B1 (OATP1B1), or P-glycoprotein 1 (P-gp) has been associated with increased risk of new or worsening muscle pain (see Overview of the pathophysiology of statin-induced myopathy section). Polypharmacy, including both prescribed and self-prescribed or over the counter medications (e.g. vitamins, minerals and herbal remedies), is a potential cause of DDIs with statins. In addition, pharmacogenetic considerations may be relevant, potentially influencing plasma concentrations of statins and in turn statin–drug interactions.

Box 2. Factors that influence the pharmacokinetics of statins and risk for statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS).

Pre-existing risk factors and co-morbidities: see Box 1

High-dose statin therapy

Polypharmacy

Drug–drug interactions: concomitant use of certain drugs including gemfibrozil, macrolides, azole antifungal agents, protease inhibitors, and immunosuppressive drugs such as cyclosporine, and inhibitors of CYP450 isoenzymes, OATP 1B1, or P-gp, can affect the metabolism of statins, increase their circulating levels and, consequently, the risk for SAMS.

-

Pharmacogenetic considerations may be relevant (see Overview of the pathophysiology of statin-induced myopathy)

CYP450, cytochrome P450; OATP 1B1, organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1B1; P-gp, P-glycoprotein 1.

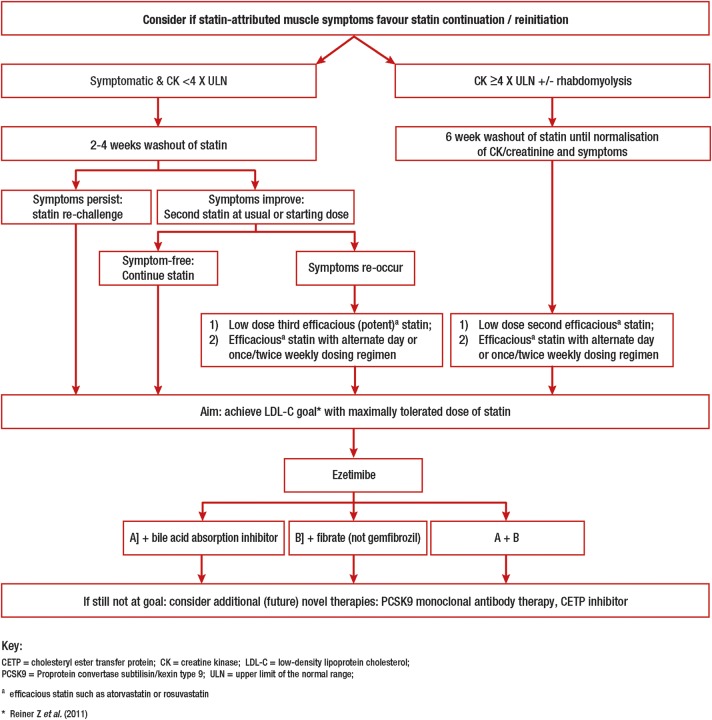

Once secondary causes and predisposing factors have been excluded, this EAS Consensus Panel recommends a review of the need for ongoing statin therapy (see Box 3 and Figure 2).

Box 3. Management of statin-associated muscle symptoms.

Ensure that there is an indication for statin use and that the patient is fully aware of the expected benefit in cardiovascular disease risk reduction that can be achieved with this treatment

Ensure that there are no contraindications to statin use

Counsel patients regarding the risk of ‘side effects’ and the high probability that these can be dealt with successfully

Emphasize dietary and other lifestyle measures

Use statin-based strategies preferentially notwithstanding the presence of statin-attributed muscle-related symptoms

If re-challenge does not work; use a low or intermittent dosing preferably of a different (potent or efficacious) statin

Use non-statin therapies as adjuncts as needed to achieve low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal

-

Do not recommend supplements to alleviate muscle symptoms as there is no good evidence to support their use

Reproduced with permission from Mancini et al.9

Figure 2.

Therapeutic flow-chart for management of patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms.

Patients with muscle symptoms with serum creatine kinase <4× upper limit of normal

The majority of patients who complain of muscle symptoms have normal or mild/moderately elevated CK levels (<4× ULN).35 For patients at low CVD risk, their need for a statin should be reassessed and the benefits of therapeutic lifestyle changes, such as cessation of cigarette smoking, blood pressure control, and adoption of a Mediterranean style diet, should be balanced against the risk of continuing statin therapy. Conversely, for those patients at high CVD risk, including those with CVD or diabetes mellitus, the benefits of ongoing statin therapy need to be weighed against the burden of muscle symptoms. Withdrawal of statin therapy followed by one or more re-challenges (after a washout) can often help in determining causality; additional approaches include the use of an alternative statin, a statin at lowest dose, intermittent (i.e. non-daily) dosing of a highly efficacious statin, or the use of other lipid lowering medications (see below).

Patients with muscle symptoms and elevated serum creatine kinase levels (>4× upper limit of normal)

For patients at low CVD risk who have symptoms with CK >4× ULN, the statin should be stopped and the need for statin reassessed. If considered important, a lower dose of an alternative statin should be tried and CK monitored. For patients at high CVD risk with muscle symptoms and a CK of >4× ULN (but <10× ULN), statin therapy can be continued with concomitant monitoring of CK, but stopped (at least temporarily) if the levels exceed 10× ULN. In this case, that particular statin regimen should not be restarted. If CK levels decrease after stopping the statin, restarting at a lower statin dose with CK monitoring should be tried. If, however, CK elevation persists, there may be an underlying myopathy (e.g. hypothyroidism or a metabolic muscle disorder), and referral to a neuromuscular specialist should be considered.

In patients with a CK >10× ULN for which no secondary cause (e.g. exercise) can be found, statin therapy should be stopped because of the potential risk of rhabdomyolysis. If the CK level subsequently returns to normal, re-challenge with a lower dose of an alternative statin and careful monitoring of symptoms and CK may be considered. If rhabdomyolysis is suspected, statin should not be reintroduced. Rhabdomyolysis should be considered if there is severe muscular pain, general weakness and signs of myoglobinaemia or myoglobinuria. These patients, and those with very high CK levels (e.g. >40× ULN), should be referred for evaluation of renal damage (urinalysis, serum creatinine levels). Intravenous hydration and urine alkalinisation are recommended for the treatment of rhabdomyolyis depending on severity and the presence of kidney injury.36 If indicated, non-statin LDL-C lowering agents should be used (see below).

Current therapy for patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms

Statin-based therapies

If symptoms/CK abnormalities resolve after discontinuation of statin, either treatment with the same statin at a lower dose or switching to an alternative statin should be considered. If tolerated, doses can be up-titrated to achieve LDL-C goal, or as much LDL-C reduction that can be achieved with minimal muscle complaints. If these strategies are not tolerated, alternate day or twice-weekly dosing can be considered to achieve the LDL-C goal. Despite methodological limitations (small size, retrospective, open label, or non-randomized design), studies have shown that either alternate day or twice-weekly dosing strategies can reduce LDL-C by 12–38%, and, importantly, are tolerated by ∼70% of previously intolerant patients.37 Generally, lower doses of a high intensity statin with a long half-life (atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, and pitavastatin) are more appropriate.

Non-statin based lipid-lowering therapy

If LDL-C remains above target despite maximally tolerated statin dosage, addition of an alternative LDL-C lowering agent should be considered in patients at high CVD risk to improve LDL-C reduction.38,39 Ezetimibe reduces LDL-C by 15–20%, is easy to take with few side effects,40 and has been shown to reduce CVD events.41 In patients with SAMS, the combination of ezetimibe plus fluvastatin XL reduced LDL-C by 46% and was as well tolerated as ezetimibe alone.42 Bile acid sequestrants can reduce LDL-C levels by 15–25% depending on the type and dose used, and may also improve glycaemia in patients with diabetes.43,44 Colesevelam is easier to take and better tolerated than earlier formulations. The combination of a bile acid sequestrant and ezetimibe can reduce LDL-C by ∼30–35%.

Fenofibrate can lower LDL-C by 15–20% in patients with high baseline levels who do not have concomitant hypertriglyceridaemia.45 This fibrate is easy to take, and has shown an excellent safety record in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes and Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes trials, although additional CVD benefit has not been demonstrated, and serum creatinine was reversibly increased during treatment.46,47 Unlike gemfibrozil, there is no increased risk of rhabdomyolysis when fenofibrate is added to a statin.48 Niacin also lowers LDL-C levels by 15–20%,49 but recent large randomized trials showed a significant excess of adverse effects and no significant CVD benefit when added to background statin treatment; therefore, niacin derivatives are no longer available for prescription in Europe.50,51

Physicians and health care professionals should therefore consider the use of ezetimibe as first choice, potentially followed by bile acid sequestrants or fibrates in combination with ezetimibe, as needed to achieve LDL-C lowering consistent with guidelines.

Nutraceuticals

In addition to adoption of a low saturated fat diet and avoidance of trans fats, consumption of viscous fibre (mainly psyllium, 10 g daily) and foods with added plant sterols or stanols (2 g daily) has also been shown to reduce LDL-C by 7% and 10%, respectively.52,53 The Portfolio diet, incorporating plant sterols, soya protein, viscous fibres, and nuts, has the potential to reduce LDL-C levels by 20–25%.54 This Panel believes that these approaches are appropriate either alone or in association with statin or non-statin drug regimens in patients with SAMS.

Complementary therapies

A number of complementary therapies, including ubiquinone (coenzyme Q10 [CoQ10]) and vitamin D supplementation, have been suggested to improve statin tolerability. A double-blind RCT and a meta-analysis,55,56 however, failed to substantiate that CoQ10, even at high doses, reduced symptoms in patients with SAMS. Evidence for the effectiveness of vitamin D is also controversial,57–60 although many patients with SAMS are found to have low blood levels of vitamin D. Hence, this Panel does not recommend supplementation with either CoQ10 or vitamin D to treat or prevent SAMS.

Red yeast rice (Monascus purpureus) is a fermented product that has been shown to reduce LDL-C levels by 20–30% in short-term RCTs.61 This effect is partly due to the presence of monacolin K, a product similar to lovastatin that inhibits hepatic cholesterol synthesis, as well as plant sterols that reduce cholesterol absorption. While recent data suggest that red yeast rice is an effective, well-tolerated approach,62 there remain a number of outstanding issues, including the lack of robust evidence that red yeast rice is efficacious and tolerated in the long term, lack of standardization with variable drug bioavailability in different preparations, and possible toxic effects due to contaminants. Furthermore, red yeast rice may also elicit SAMS because of the statin-like content. Long-term, rigorously designed RCTs are needed before red yeast rice could be recommended to patients with increased CVD risk.

Future low-density lipoprotein-lowering therapies for patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms

Two classes of novel therapies, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors and cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors, offer potential as alternatives for the management of patients with persistent SAMS.

PSCK9 inhibitors

PCSK9 is a circulating protein that binds to the LDL receptor and targets it for degradation.63 First identified in 2003 and shown to be related to autosomal-dominant hypercholesterolaemia, PCSK9 has become a therapeutic target for potently reducing LDL-C in humans.64,65 Clinical development of human monoclonal antibodies has progressed very rapidly, with the most advanced being evolocumab, alirocumab, and bococizumab. Studies have consistently shown large LDL-C reductions of 50–60% in a variety of patient groups,64,65 including those identified as statin intolerant,66–68 with a very low rate of muscle symptoms, thus reinforcing the concept that statin rather than LDL-C lowering is implicated in the causation of myopathy. In clinical trials including over 6000 patients treated for 3 to 12 months, the tolerability of these subcutaneously administered drugs has been very good, with few injection site reactions and no significant liver function abnormalities or CK elevations.69,70 Four large CVD outcomes trials are ongoing and initial results are anticipated in 2017.71–74

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein mediates the heteroexchange of triglycerides and cholesteryl esters between lipoproteins. Inhibitors of CETP can markedly increase high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and two members of this class in advanced development, anacetrapib and evacetrapib, equally lower LDL-C by 25–40%.75,76 The mechanism for LDL-C lowering involves increased fractional removal rates for LDL apolipoprotein B from plasma although the molecular basis for this is unclear. Importantly, no side effects involving the musculoskeletal system have been identified with CETP inhibitors. Two large clinical trials to determine whether anacetrapib or evacetrapib reduce CVD events in high-risk patients are underway.77,78

Overview of the pathophysiology of statin-induced myopathy

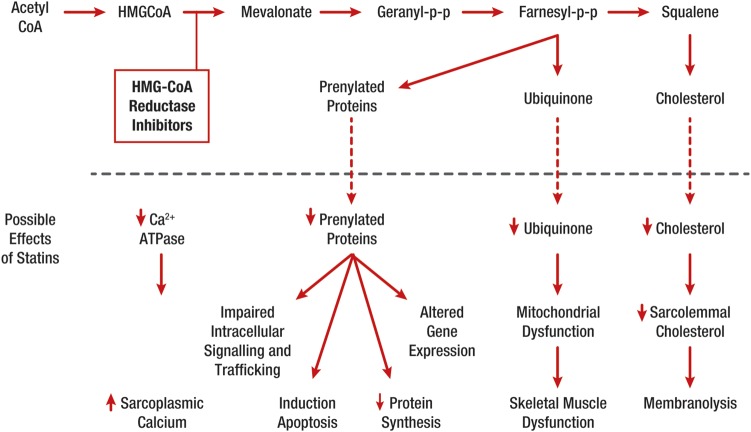

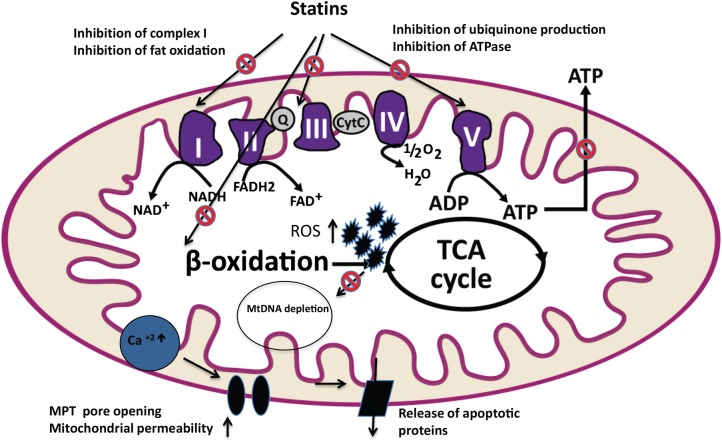

Our understanding of the pathophysiology of SAMS and statin-induced myopathy remains elusive, although several mechanisms have been proposed (see Figure 3, Supplementary material online, Table S3).79 Interest has focused primarily on altered cellular energy utilization and mitochondrial function (Figure 4, Box 4).80–95 Abnormal mitochondrial function with depletion of CoQ10 have been reported during statin therapy, even in asymptomatic statin users. Some argue that this may be unmasking previously undiagnosed mitochondrial pathology (see Supplementary material online, Table S4).96 Notably, insulin-resistant obese individuals, or those with a family history of, or with overt type 2 diabetes, frequently exhibit reduction in both muscle ATP turnover and oxidative capacity.97,98 The effects of statins on muscle mitochondria have been detected by various methods ranging from morphometry to in vivo magnetic response spectroscopy, all of which test different features of mitochondrial function.96

Figure 3.

Effects potentially involved in statin-related muscle injury/symptoms (Reproduced with permission from Needham and Mastaglia 2014).79 A number of statin-mediated effects have been proposed including reduced levels of non-cholesterol end-products of the mevalonate pathway; reduced sarcolemmal and/or sarcoplasmic reticular cholesterol; increased myocellular fat and/or sterols; inhibition of production of prenylated proteins or guanosine triphosphate (GTP)ases; alterations in muscle protein catabolism; decreased myocellular creatine; changes in calcium homeostasis; immune-mediated effects of statins and effects on mitochondrial function—see Figure 4 and Box 4. Ca2+ATPase, calcium ATPase; HMG CoA, 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA; PP, pyrophosphate.

Figure 4.

Possible targets of statins in the mitochondrion with deleterious effects on muscle function. The interaction of statins with muscle mitochondria can involve (i) reduced production of prenylated proteins including the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) protein, ubiquinone (coenzyme Q10), (ii) subnormal levels of farnesyl pyrophosphate and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate leading to impaired cell growth and autophagy, (iii) low membrane cholesterol content affecting membrane fluidity and ion channels, and (iv) the triggered calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum via ryanodine receptors, resulting in impaired calcium signalling.92–94 Statin-induced depletion of myocellular ubiquinone, an essential coenzyme which participates in electron transport during oxidative phosphorylation,95 may attenuate electron transfer between complexes I, III, and II of ETC. ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Cyt C, cytochrome C; FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide; FADH2, flavin adenine dinucleotide reduced; MPT, mitochondrial permeability transition; MtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NADH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; ROS, reactive oxidative species; TCA cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Box 4. Statin-induced myopathy mediated by abnormal mitochondrial function: what is the evidence?

Histochemical findings: muscle biopsies from four patients with statin-associated myopathy and normal creatine kinase (CK) levels showed findings consistent with abnormal mitochondrial function, including increased intramuscular lipid content, diminished cytochrome oxidase staining, and ragged red fibres.80 One study showed muscle injury in 25 of 44 patients with myopathy and in one patient taking statin without myopathy,81 whereas another study reported unchanged muscle structure in 14 of 18 patients with statin-induced increased CK levels.82

Decreased mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA): reduced levels were found in skeletal muscle biopsies taken from patients treated with simvastatin 80 mg/day for 8 weeks but not in those treated with atorvastatin 40 mg/day.83 There was a positive overall correlation between changes in muscle ubiquinone and the change in mtDNA/nuclear DNA ratios (R = 0.63, P < 0.01), which was strongest in the simvastatin group (R = 0.76, P < 0.002). A cross-sectional study in 23 patients with simvastatin- or atorvastatin-induced myopathy also revealed low mtDNA/nuclear DNA ratios.84

Activity of complex III of the mitochondrial respiratory chain: activity of this complex and concentrations of high-energy phosphates were found to be unchanged in statin-treated patients, suggesting that mitochondrial function was not compromised.82,85 Another study reported lower expression of complex I, II, III, and IV after 8 weeks of simvastatin, but not after atorvastatin treatment despite similar reduction in coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10, also known as ubiquinone).86 Of note, these studies were performed at rest, and may not reflect mitochondrial function during exercise.

Lower mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS): this was observed in chronic simvastatin users (mean ± SD, 5 ± 5 years) compared with untreated persons. Mitochondrial density assessed by citrate synthase activity (CSA) did not differ between the two groups, but there was an increase in the ratio of mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channels (VDAC) to CSA suggesting more channels per mitochondrion. Voltage-dependent anion channel helps regulate mitochondrial calcium content, and an increase in mitochondrial calcium content facilitates apoptosis. Mitochondrial OXPHOS can also be assessed in vivo from post-exercise phosphocreatine recovery using 31-phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy. These measurements showed a prolonged recovery half-life during statin treatment even in the absence of any symptoms or overt CK changes.87

Effects of exercise. Using respiratory exchange ratios during exercise as an indirect measure of mitochondrial function, several small studies have suggested the possibility of statin-induced abnormalities in mitochondrial function during exercise.88

Based on these observations, it is likely that statins decrease mitochondrial function, attenuate energy production, and alter muscle protein degradation, each of which may contribute to the onset of muscle symptoms.99 However, progress has been hampered by the fact that myopathy has been difficult to induce with statin treatment in preclinical models.100–103 Only recently, mice with genetically induced deficiency of lipin-1, a phosphatidic acid phosphatase, were shown to develop myopathy/myositis that was associated with impaired autophagy and the presence of abnormal mitochondria.104 In this model, myopathy/myositis could be aggravated by co-administration of statins, whereas both lipin-1 deficiency and statins were found to attenuate autolysosome maturation.

In patients, persistent myopathy has been suggested to reflect structural muscle damage.81 Muscle biopsy studies in a limited number of patients with SAMS and normal CK levels suggested a role for abnormal mitochondrial function.80,81 Conversely, other studies in patients with statin-induced SAMS with CK elevations were unable to demonstrate structural abnormalities in muscle cells.82 Although rare, it has also been suggested that statins may trigger idiopathic inflammatory myositis or immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Thus, statins increase the risk for development of anti-HMG-CoA-reductase antibodies, dependent upon statin exposure, male gender, diabetes, and genetic background.35,105 Overall, notwithstanding promising preclinical data, it is still not clear what the underlying pathophysiological mechanism(s) is in patients with SAMS.

Genetic susceptibility to statin-associated muscle symptoms

While genetic testing in patients with statin myopathy has not yet become commonplace, there are some clear genetic signals, with variants of genes encoding drug transporters in both the liver and skeletal muscle that increase serum statin concentration linked to muscle side effects (see Supplementary material online, Table S5).106–109 The most significant associations have been single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in SLCO1B1, encoding OATP1B1.110 The SEARCH genome-wide association study of SLCO1B1 variants identified a defective rs4149056 SNP in strong linkage disequilibrium with the c.521T_C SNP, which, in homozygotes, was associated with an 18% risk of muscle symptoms with high-dose simvastatin compared with heterozygotes (3%); in those without risk alleles, the risk of muscle symptoms was 0.6%.111

An increased frequency of pathogenic variants in muscle-disease-associated genes has been reported,96,112–114 with a 13- to 20-fold higher incidence in subjects with severe myopathy compared with the general population.96,112,113 In one study, 17.1% of patients with severe statin myopathy and 16.1% of patients with non-statin-induced exertional rhabdomyolysis had pathogenic variants in 12 muscle disease genes studied vs. 4.5% of statin-tolerant controls.113 Other candidate genes for statin-induced myalgia have been identified,115 each with a plausible pathophysiological relationship to muscle metabolism, but without adequate evidence to support their clinical relevance. Glycine amidinotransferase (GATM) catalyses a critical step in hepatic and renal synthesis of creatine, used in muscle to form creatine phosphate, which is a major source of energy storage in muscle. Two independent studies showed that genotypes associated with statin-induced down-regulation of expression of the gene encoding GATM were associated with protection from statin-induced myopathy.116 Other investigators, however, were unable to replicate the association between the rs9806699 GATM SNP and statin myopathy.117 Clearly, further studies will be required to determine a mechanistic basis for a contribution of genetic variation in GATM to the risk of SAMS. Potential non-disease candidate genes whose products might be determinants of statin-attributed muscle symptoms include those encoding enzymes involved in drug metabolism and disposition, mitochondrial function, or ubiquitination.79,118

Genotyping of patients with personal or family histories of muscle disease who develop SAMS has been suggested as a means of diagnosing underlying muscle disease.19 Candidates for genetic testing may also include patients with documented prolonged statin-associated muscle symptoms >6 months post-therapy,112 and symptomatic patients with plasma CK >4× ULN.114 Targeted next-generation sequencing of muscle disease genes in these high-risk individuals will certainly become more prominent in diagnosing individuals at risk. Identification of underlying genetic risk factors may contribute to improved therapeutic compliance through careful monitoring of conservative therapy. At present, however, there is insufficient evidence to recommend genetic testing as a part of the diagnostic work-up of patients with SAMS.

Conclusions

Lowering LDL-C with statin therapy reduces CVD risk by up to 40% in a wide range of patients. Given that the main reason for statin non-adherence/discontinuation relates to the onset of (perceived) side effects, it follows that the high prevalence of SAMS reported from observational studies is likely to adversely affect the CVD benefits of statins.119 Strategies to prevent the loss of effective statin therapy because of SAMS are still lacking. In the absence of a gold standard definition, this EAS Consensus Panel proposes to base the probability of SAMS being caused by statins on the nature of symptoms and their temporal relationship with statin initiation, statin discontinuation (or dechallenge), and repetitive re-challenge (Figure 2). Optimal therapy should combine a maximally tolerated, or even non-daily statin dose, together with non-statin-based lipid-lowering therapies in order to achieve LDL-C targets.

This Consensus Panel also highlights the need for further research into the pathophysiology of SAMS. Accumulating preclinical data show that statins decrease mitochondrial function, and alter muscle protein degradation, providing a possible pathophysiological link between statins and muscle symptoms. Studies in the clinical setting are a priority to further understanding of these mechanisms, and may offer therapeutic potential. In the absence of therapies to prevent these symptoms, this Consensus Panel recommends that the response of patients with SAMS to three or more statins should be considered for referral to specialized settings. By recognizing SAMS and adhering to a structured work-up, the Panel anticipates that individuals with clinically relevant SAMS will be offered alternative and/or novel therapeutic regimens that can satisfactorily address their CVD risk.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

This work was supported by unrestricted educational grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Esperion, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Regeneron. These companies were not present at the Consensus Panel meetings, had no role in the design or content of the manuscript, and had no right to approve or disapprove the final document. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the European Atherosclerosis Society.

Conflict of interest: The following disclosures are provided for honoraria for lectures/advisory boards, consultancy, travel support and/or research grants.

Abbott [Solvay] (H.N.G., K.K.R., A.C., L.T.); Actelion (L.T.); Aegerion Pharmaceuticals (E.B., R.D.S., R.A.H., L.A.L., B.G.N., A.L.C., G.K.H., K.K.R., L.T., W.M.); Amgen (H.N.G., E.B., A.C., F.J.R., R.D.S., L.T., R.A.H., U.L., L.A.L., B.G.N., A.L.C., G.K.H., K.K.R., M.J.C., E.A.S., W.M.); AstraZeneca (E.B., A.C., L.A.L., H.N.G., F.J.R., R.D.S., E.A.S., E.S., L.T., T.A.J., B.G.N., A.L.C., K.K.R., O.W., W.M., M.J.C., E.S.); Bayer (L.T.); BASF (W.M.); Biolab (R.D.S.); Boehringer-Ingelheim (H.N.G., L.A.L., K.K.R., R.D.S., L.T.); Bristol-Myers-Squibb (H.N.G., L.A.L., K.K.R., R.D.S.); Chiesi (E.B.); CSL (M.J.C.); Daiichi (K.K.R., L.T.); Danone (E.B., W.M., M.J.C.); Fresenius (B.G.N.); Genfit (E.B.); Genzyme (E.B., H.N.G., R.D.S., A.L.C., G.K.H., W.M., M.J.C.); GlaxoSmithKline (L.T.); Hoffman-La Roche (E.B., H.N.G., K.K.R., M.J.C., E.A.S., W.M.); ISIS Pharmaceuticals (F.J.R., R.D.S., R.M.K., B.G.N.); Janssen (L.A.L., H.N.G.); Kowa (H.N.G., A.L.C., A.C., K.K.R., L.T., M.J.C.); Kraft (E.B.); Ligand Pharmaceuticals (R.M.K.); Lilly (A.L.C., A.C., U.L., L.A.L., K.K.R., R.D.S., L.T); Madrigal Pharmaceuticals (R.M.K.); MedChefs (R.M.K.); Mediolanum (A.L.C., A.C.); Menarini (L.T.); Merck (E.B., H.N.G., A.C., R.D.S., E.S., R.A.H., T.A.J., R.M.K., U.L., L.A.L., B.G.N., A.L.C., F.J.R., K.K.R., L.T., O.W., W.M., M.J.C.); Metabolex (R.M.K.); Nestle (R.D.S.); NiCox (A.C.); Novartis (H.N.G., K.K.R.); Novo-Nordisk (L.A.L., R.D.S., K.K.R., L.T.); Numares (W.M.); Omthera (A.L.C., B.G.N.); Pfizer (H.N.G., R.D.S., R.A.H., U.L., B.G.N., A.L.C, G.K.H., F.J.R., K.K.R., L.T., O.W., W.M., M.J.C., E.S.); Quest Diagnostics (R.M.K.); Recordati (A.L.C.); Rottapharm (A.L.C.), Roche/Genentech (E.A.S.); Sanofi-Aventis/Regeneron (E.B., A.C., T.A.J., R.M.K., U.L., L.A.L., H.N.G., F.J.R., R.D.S., E.A.S., L.T., R.A.H., B.G.N., A.L.C., G.K.H., K.K.R., O.W., W.M., M.J.C., E.S.); Servier (L.T.); Sigma-Tau (A.L.C.); Synageva (G.K.H., W.M.); Tribute (R.A.H.); Synlab (W.M.); Unilever (E.B., M.J.C., R.D.S., W.M.); Valeant (R.A.H., L.A.L.).

G.D.B., F.M., C.B.N., M.R., P.D.T., and G.D.V. declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This EAS Consensus Panel gratefully acknowledges Dr Sune F. Nielsen, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, for preparation of Figure 1. The authors are indebted to Dr Jane Stock for editorial support. We equally express our appreciation to Sherborne Gibbs Ltd for logistical support.

Appendix: EAS consensus panel writing committee

Erik Stroes (ES, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), Paul D. Thompson (Hartford Hospital, Hartford, Connecticut, USA), Alberto Corsini (University of Milan and Multimedica IRCSS Milano, Italy), Georgirene D. Vladutiu (School of Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA), Frederick J. Raal (University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa), Kausik K. Ray (St. Georges's University of London, UK), Michael Roden (Department of Endocrinology and Diabetology, University Hospital Düsseldorf Heinrich-Heine University, and Institute for Clinical Diabetology, German Diabetes Center, Leibniz Center for Diabetes Research, Germany), Evan Stein (Metabolic and Atherosclerosis Research Centre, Cincinnati, OH, USA), Lale Tokgözoğlu (Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey), Børge G. Nordestgaard (Herlev Hospital, Copenhagen University Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Denmark), Eric Bruckert (Pitié-Salpetriere University Hospital, Paris, France), , Ronald M. Krauss (Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute, Oakland, California, USA), Ulrich Laufs (Universitätsklinikum des Saarlandes, Homburg/Saar, Germany), Raul D. Santos (University of Sao Paulo, Brazil), Winfried März (Synlab Center of Laboratory Diagnostics Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany), Connie B. Newman (New York University School of Medicine, New York, USA), M. John Chapman (INSERM, Pitié-Salpetriere University Hospital, Paris, France), Henry N. Ginsberg (Columbia University, New York, USA).

Co-chairs: M. John Chapman (MJC) and Henry N. Ginsberg (HNG).

Other Panel Members: Guy de Backer (Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium), Alberico L. Catapano (University of Milan and Multimedica IRCSS Milano, Italy), Robert A. Hegele (Western University, London, ON, Canada), G. Kees Hovingh (Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Terry A. Jacobson (Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA), Lawrence Leiter (Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute and Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science, St. Michael's Hospital, University of Toronto, Canada), Francois Mach (Cardiology Service, HUG, Geneva, Switzerland), Olov Wiklund (Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden).

The Panel met three times in London, Barcelona and Madrid at meetings chaired by MJC and HNG. The first meeting critically reviewed the literature, and the second and third meetings scrutinized drafts of this review. Each drafted section and the complete draft was revised by ES, MJC, and HNG. All Panel members agreed to the conception and design of the review, contributed to interpretation of available data, and suggested revisions. All Panel members approved the final document before submission.

References

- 1.Reiner Z, Catapano AL, De Backer G, Graham I, Taskinen MR, Wiklund O, Agewall S, Alegria E, Chapman MJ, Durrington P, Erdine S, Halcox J, Hobbs R, Kjekshus J, Filardi PP, Riccardi G, Storey RF, Wood D. ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J 2011;32:1769–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:7–22.12114036 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Jr, Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, MacFadyen JG, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Willerson JT, Glynn RJ; JUPITER Study Group. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2195–2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kashani A, Phillips CO, Foody JM, Wang Y, Mangalmurti S, Ko DT, Krumholz HM. Risks associated with statin therapy: a systematic overview of randomized clinical trials. Circulation 2006;114:2788–2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Lancet 2000;355:253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Beevers G, de Faire U, Fyhrquist F, Ibsen H, Kristiansson K, Lederballe-Pedersen O, Lindholm LH, Nieminen MS, Omvik P, Oparil S, Wedel H; LIFE Study Group. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet 2002;359:995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Law M, Rudnicka AR. Statin safety: a systematic review. Am J Cardiol 2006;97:52C–60C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter AA, Gomes T, Camacho X, Juurlink DN, Shah BR, Mamdani MM. Risk of incident diabetes among patients treated with statins: population based study. BMJ 2013;346:2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mancini GB, Tashakkor AY, Baker S, Bergeron J, Fitchett D, Frohlich J, Genest J, Gupta M, Hegele RA, Ng DS, Pearson GJ, Pope J. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of statin adverse effects and intolerance: Canadian Working Group Consensus update. Can J Cardiol 2013;29:1553–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson K, Schoen M, French B, Umscheid CA, Mitchell MD, Arnold SE, Heidenreich PA, Rader DJ, de Goma EM. Statins and cognitive function: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:688–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, Yau C, Begaud B. Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients—the PRIMO study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2005;19:403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buettner C, Rippberger MJ, Smith JK, Leveille SG, Davis RB, Mittleman MA. Statin use and musculoskeletal pain among adults with and without arthritis. Am J Med 2012;125:176–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Ito MK, Jacobson TA. Understanding statin use in America and gaps in patient education (USAGE): an internet-based survey of 10,138 current and former statin users. J Clin Lipidol 2012;6:208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, Morrison F, Mar P, Shubina M, Turchin A. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: a cohort study. Ann Int Med 2013;158:526–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Salem K, Ababeneh B, Rudnicki S, Malkawi A, Alrefai A, Khader Y, Saadeh R, Saydam M. Prevalence and risk factors of muscle complications secondary to statins. Muscle Nerve 2011;44:877–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chodick G, Shalev V, Gerber Y, Heymann AD, Silber H, Simah V, Kokia E. Long-term persistence with statin treatment in a not-for-profit health maintenance organization: a population-based retrospective cohort study in Israel. Clin Ther 2008;30:2167–2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackevicius CA, Mamdani M, Tu JV. Adherence with statin therapy in elderly patients with and without acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2002;288:462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chowdhury R, Khan H, Heydon E, Shroufi A, Fahimi S, Moore C, Stricker B, Mendis S, Hofman A, Mant J, Franco OH. Adherence to cardiovascular therapy: a meta-analysis of prevalence and clinical consequences. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2940–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenson RS, Baker SK, Jacobson TA, Kopecky SL, Parker BA. An assessment by the statin muscle safety task force: 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol 2014;8:558–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganga HV, Slim HB, Thompson PD. A systematic review of statin-induced muscle problems in clinical trials. Am Heart J 2014;168:6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finegold JA, Manisty CH, Goldacre B, Barron AJ, Francis DP. What proportion of symptomatic side effects in patients taking statins are genuinely caused by the drug? Systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials to aid individual patient choice. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2014;21:464–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker BA, Capizzi JA, Grimaldi AS, Clarkson PM, Cole SM, Keadle J, Chipkin S, Pescatello LS, Simpson K, White CM, Thompson PD. Effect of statins on skeletal muscle function. Circulation 2013;127:96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keech A, Collins S, MacMahon S, Armitage J, Lawson A, Wallendszus K, Fatemian M, Kearney E, Lyon V, Mindell J, Mount J, Painter R, Parish S, Slavin B, Sleight P, Youngman L, Peto R. Three-year follow-up of the Oxford Cholesterol Study: assessment of the efficacy and safety of simvastatin in preparation for a large mortality study. Eur Heart J 1994;15:255–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. Effects of simvastatin 40 mg daily on muscle and liver adverse effects in a 5-year randomized placebo-controlled trial in 20,536 high-risk people. BMC Clin Pharmacol 2009;9:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mampuya WM, Frid D, Rocco M, Huang J, Brennan DM, Hazen SL, Cho L. Treatment strategies in patients with statin intolerance: the Cleveland Clinic experience. Am Heart J 2013;166:597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG, Bojesen SE. Statin use and reduced cancer-related mortality. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1792–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG. Statin use before diabetes and risk of microvascular disease: a nationwide nested matched study. Lancet Diabet Endocrinol 2014;2:894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasternak RC, Smith SC, Jr, Bairey-Merz CN, Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Lenfant C; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. ACC/AHA/NHLBI Clinical advisory on the use and safety of statins. Circulation 2002;106:1024–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Downs JR, Clearfield M, Tyroler HA, Whitney EJ, Kruyer W, Langendorfer A, Zagrebelsky V, Weis S, Shapiro DR, Beere PA, Gotto AM. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (AFCAPS/TexCAPS). Additional perspectives on tolerability of long-term treatment with lovastatin. Am J Cardiol 2001;87:1074–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armitage J. The safety of statins in clinical practice. Lancet 2007;370:1781–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joy TR, Hegele RA. Narrative review: statin-related myopathy. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:858–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corsini A. The safety of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors in special populations at high cardiovascular risk. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2003;17:265–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armitage J, Baigent C, Collins R. Misrepresentation of statin safety evidence. Lancet 2014;384:1263–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmad Z. Statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:1765–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alfirevic A, Neely D, Armitage J, Chinoy H, Cooper RG, Laaksonen R, Carr DF, Bloch KM, Fahy J, Hanson A, Yue QY, Wadelius M, Maitland-van Der Zee AH, Voora D, Psaty BM, Palmer CN, Pirmohamed M. Phenotype standardization for statin-induced myotoxicity. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2014;96:470–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bosch X, Poch E, Grau JM. Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med 2009;361:62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keating AJ, Campbell KB, Guyton JR. Intermittent nondaily dosing strategies in patients with previous statin-induced myopathy. Ann Pharmacother 2013;47:398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Athyros VG, Tziomalos K, Kakafika AI, Koumaras H, Karagiannis A, Mikhailidis DP. Effectiveness of ezetimibe alone or in combination with twice a week atorvastatin (10 mg) for statin intolerant high-risk patients. Am J Cardiol 2008;101:483–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reddy KJ, Singh M, Batsell RR, Bangit JR, Zaheer MS, John S, Varghese S, Molinella R. Efficacy of combination drug pulse therapy in maintaining lipid levels in patients intolerant of daily statin use. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2009;11:766–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Norata GD, Ballantyne CM, Catapano AL. New therapeutic principles in dyslipidaemia: focus on LDL and Lp(a) lowering drugs. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1783–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cannon CP, IMPROVE-IT Investigators. IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized study to establish the clinical benefit and safety of Vytorin (ezetimibe/simvastatin tablet) vs simvastatin monotherapy in high-risk subjects presenting with acute coronary syndrome. http://my.americanheart.org/idc/groups/ahamah-public/@wcm/@sop/@scon/documents/downloadable/ucm_469669.pdf (22 November 2014).

- 42.Stein EA, Ballantyne CM, Windler E, Sirnes PA, Sussekov A, Yigit Z, Seper C, Gimpelewicz CR. Efficacy and tolerability of Fluvastatin XL 80 mg alone, ezetimibe alone and the combination of Fluvastatin XL 80 mg with ezetimibe in patients with a history of muscle-related side effects with other statins: a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy trial. Am J Cardiol 2008;101:490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davidson MH, Dillon MA, Gordon B, Jones P, Samuels J, Weiss S, Isaacsohn J, Toth P, Burke SK. Colesevelam hydrochloride (cholestagel): a new, potent bile acid sequestrant associated with a low incidence of gastrointestinal side effects. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1893–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heel RC, Brogden RN, Pakes GE, Speight TM, Avery GS. Colestipol: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in patients with hypercholesterolaemia. Drugs 1980;19:161–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knopp RH, Brown WV, Dujovne CA, Farquhar JW, Feldman EB, Goldberg AC, Grundy SM, Lasser NL, Mellies MJ, Palmer RH. Effects of fenofibrate on plasma lipoproteins in hypercholesterolemia and combined hyperlipidemia. Am J Med 1987;83:50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.ACCORD Study Group Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, Crouse JR, III, Leiter LA, Linz P, Friedewald WT, Buse JB, Gerstein HC, Probstfield J, Grimm RH, Ismail-Beigi F, Bigger JT, Goff DC, Jr, Cushman WC, Simons-Morton DG, Byington RP. Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1563–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keech A, Simes RJ, Barter P, Best J, Scott R, Taskinen MR, Forder P, Pillai A, Davis T, Glasziou P, Drury P, Kesäniemi YA, Sullivan D, Hunt D, Colman P, d'Emden M, Whiting M, Ehnholm C, Laakso M; FIELD study investigators. Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;366:1849–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo J, Meng F, Ma N, Li C, Ding Z, Wang H, Hou R, Qin Y. Meta-analysis of safety of the coadministration of statin with fenofibrate in patients with combined hyperlipidemia. Am J Cardiol 2012;110:1296–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Capuzzi DM, Guyton JR, Morgan JM, Goldberg AC, Kreisberg RA, Brusco OA, Brody J. Efficacy and safety of an extended-release niacin (Niaspan): a long-term study. Am J Cardiol 1998;82:74U–81U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.AIM-HIGH Investigators Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, Chaitman BR, Desvignes-Nickens P, Koprowicz K, McBride R, Teo K, Weintraub W. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2255–2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.HPS2-THRIVE Collaborative Group. HPS2-THRIVE randomized placebo-controlled trial in 25 673 high-risk patients of ER niacin/laropiprant: trial design, pre-specified muscle and liver outcomes, and reasons for stopping study treatment. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1279–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anderson JW, Davidson MH, Blonde L, Brown WV, Howard WJ, Ginsberg H, Allgood LD, Weingand KW. Long term cholesterol-lowering effects of psyllium as an adjunct to diet therapy in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;71:1433–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gylling H, Plat J, Turley S, Ginsberg HN, Ellegård L, Jessup W, Jones PJ, Lütjohann D, Maerz W, Masana L, Silbernagel G, Staels B, Borén J, Catapano AL, De Backer G, Deanfield J, Descamps OS, Kovanen PT, Riccardi G, Tokgözoglu L, Chapman MJ; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel on Phytosterols. Plant sterols and plant stanols in the management of dyslipidaemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2014;232:346–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jenkins DJ, Jones PJ, Lamarche B, Kendall CW, Faulkner D, Cermakova L, Gigleux I, Ramprasath V, de Souza R, Ireland C, Patel D, Srichaikul K, Abdulnour S, Bashyam B, Collier C, Hoshizaki S, Josse RG, Leiter LA, Connelly PW, Frohlich J. Effect of a dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods given at 2 levels of intensity of dietary advice on serum lipids in hyperlipidemia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2011;306:831–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor BA, Lorson L, White CM, Thompson PD. A randomized trial of Coenzyme Q10 in patients with confirmed statin myopathy. Atherosclerosis 2015;238:329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Banach M, Serban C, Sahebkar A, Ursoniu S, Rysz J, Muntner P, Toth PP, Jones SR, Rizzo M, Glasser SP, Lip GYH, Dragan S, Mikhailidis DP, Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta-analysis Collaboration (LBPMC) Group. Effects of Coenzyme Q10 on statin-induced myopathy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Mayo Clinic Proc 2015;90:24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bookstaver DA, Burkhalter N, Hatzigeorgiou C. Effect of Coenzyme Q10 supplementation on statin-induced myalgias. Am J Cardiol 2012;110:526–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caso G, Kelly P, McNurlan MA, Lawson WE. Effect of Coenzyme Q10 on myopathic symptoms in patients treated with statins. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:1409–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pfeifer M, Begerow B, Minne HW. Vitamin D and muscle function. Osteoporos Int 2012;13:187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Michalska-Kasiczak M, Sahebkar A, Mikhailidis DP, Rysz J, Muntner P, Toth PP, Jones SR, Rizzo M, Kees Hovingh G, Farnier M, Moriarty PM, Bittner VA, Lip GY, Banach M; Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta-analysis Collaboration (LBPMC) Group., Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta-analysis Collaboration (LBPMC) Group. Analysis of vitamin D levels in patients with and without statin-associated myalgia – a systematic review and meta-analysis of 7 studies with 2420 patients. Int J Cardiol 2014;178C:111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mannarino MR, Ministrini S, Pirro M. Nutraceuticals for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Eur J Intern Med 2014;25:592–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li Y, Jiang L, Jia Z, Xin W, Yang S, Yang Q, Wang L. A meta-analysis of red yeast rice: an effective and relatively safe alternative approach for dyslipidemia. PLoS One 2014;9:e98611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lambert G, Sjouke B, Choque B, Kastelein JJ, Hovingh GK. The PCSK9 decade: thematic review series: new lipid and lipoprotein targets for the treatment of cardiometabolic diseases. J Lipid Res 2012;53:2515–2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stein EA, Raal F. Reduction of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by monoclonal antibody inhibition of PCSK9. Annu Rev Med 2014;65:417–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Norata GD, Tibolla G, Catapano AL. Targeting PCSK9 for hypercholesterolemia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2014;54:273–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stroes E, Colquhoun D, Sullivan D, Civeira F, Rosenson RS, Watts GF, Bruckert E, Cho L, Dent R, Knusel B, Xue A, Scott R, Wasserman SM, Rocco M; GAUSS-2 Investigators. Anti-PCSK9 antibody effectively lowers cholesterol in patients with statin intolerance: the GAUSS-2 randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial of evolocumab. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2541–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sullivan D, Olsson AG, Scott R, Kim JB, Xue A, Gebski V, Wasserman SM, Stein EA. Effect of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9 on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in statin-intolerant patients: the GAUSS randomized trial. JAMA 2012;308:2497–2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moriarty PM, Thompson PD, Cannon CP, Guyton JR, Bergeron J, Zıeve FJ, Bruckert E, Jacobson TA, Baccara-Dinet MT, Zhao J, Du Y, Pordy R, Gipe D. ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE: efficacy and safety of alirocumab versus ezetimibe, in patients with statin intolerance as defined by a placebo run-in and statin rechallenge arm. http://my.americanheart.org/idc/groups/ahamah-public/@wcm/@sop/@scon/documents/downloadable/ucm_469684.pdf (22 November 2014).

- 69.Stein EA, Giugliano RP, Koren MJ, Raal FJ, Roth EM, Weiss R, Sullivan D, Wasserman SM, Somaratne R, Kim JB, Yang J, Liu T, Albizem M, Scott R, Sabatine MS. Efficacy and safety of evolocumab (AMG 145), a fully human monoclonal antibody to PCSK9, in hyperlipidaemic patients on various background lipid therapies: pooled analysis of 1359 patients in 4 Phase 2 trials. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2249–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tavori H, Melone M, Rashid S. Alirocumab: PCSK9 inhibitor for LDL cholesterol reduction. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2014;12:1137–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.ClinicalTrials.gov. Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk (FOURIER). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01764633 http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01764633 (10 December 2014).

- 72.ClinicalTrials.gov. ODYSSEY Outcomes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes After an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment With Alirocumab SAR236553 (REGN727). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01663402 http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01663402 (10 December 2014).

- 73.ClinicalTrials.gov. The Evaluation of Bococizumab (PF-04950615) In Reducing The Occurrence Of Major Cardiovascular Events In High Risk Subjects (SPIRE-1). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01975376 http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01975376 (10 December 2014).

- 74.ClinicalTrials.gov. The Evaluation of Bococizumab (PF-04950615) In Reducing The Occurrence Of Major Cardiovascular Events In High Risk Subjects (SPIRE-2). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01975389 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01975389 (10 December 2014).

- 75.Davidson M, Liu SX, Barter P, Brinton EA, Cannon CP, Gotto AM, Jr, Leary ET, Shah S, Stepanavage M, Mitchel Y, Dansky HM. Measurement of LDL-C after treatment with the CETP inhibitor anacetrapib. J Lipid Res 2013;54:467–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nicholls SJ, Brewer HB, Kastelein JJ, Krueger KA, Wang MD, Shao M, Hu B, McErlean E, Nissen SE. Effects of the CETP inhibitor evacetrapib administered as monotherapy or in combination with statins on HDL and LDL cholesterol: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2011;306:2099–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.ClinicalTrials.gov. REVEAL: Randomized EValuation of the Effects of Anacetrapib Through Lipid-modification. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01252953 http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01252953 (10 December 2014).

- 78.ClinicalTrials.gov. A Study of Evacetrapib in High-Risk Vascular Disease (ACCELERATE). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01687998 http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01687998 (10 December 2014).

- 79.Needham M, Mastaglia FL. Statin myotoxicity: a review of genetic susceptibility factors. Neuromuscul Disord 2014;24:4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Phillips PS, Haas RH, Bannykh S, Hathaway S, Gray NL, Kimura BJ, Vladutiu GD, England JD; Scripps Mercy Clinical Research Center. Statin-associated myopathy with normal creatine kinase levels. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:581–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mohaupt MG, Karas RH, Babiychuk EB, Sanchez-Freire V, Monastyrskaya K, Iyer L, Hoppeler H, Breil F, Draeger A. Association between statin-associated myopathy and skeletal muscle damage. CMAJ 2009;181:E11–E18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lamperti C, Naini AB, Lucchini V, Prelle A, Bresolin N, Moggio M, Sciacco M, Kaufmann P, DiMauro S. Muscle coenzyme Q10 level in statin-related myopathy. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1709–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schick BA, Laaksonen R, Frohlich JJ, Päivä H, Lehtimäki T, Humphries KH, Côté HC. Decreased skeletal muscle mitochondrial DNA in patients treated with high-dose simvastatin. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007;81:650–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stringer HA, Sohi GK, Maguire JA, Côté HC. Decreased skeletal muscle mitochondrial DNA in patients with statin-induced myopathy. J Neurol Sci 2013;325:142–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Laaksonen R, Jokelainen K, Laakso J, Sahi T, Harkonen M, Tikkanen MJ, Himberg JJ. The effect of simvastatin treatment on natural antioxidants in low-density lipoproteins and high-energy phosphates and ubiquinone in skeletal muscle. Am J Cardiol 1996;77:851–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Päivä H, Thelen KM, Van Coster R, Smet J, De Paepe B, Mattila KM, Laakso J, Lehtimäki T, von Bergmann K, Lütjohann D, Laaksonen R. High-dose statins and skeletal muscle metabolism in humans: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2005;78:60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu JS, Buettner C, Smithline H, Ngo LH, Greenman RL. Evaluation of skeletal muscle during calf exercise by 31-phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy in patients on statin medications. Muscle Nerve 2011;43:76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marcoff L, Thompson PD. The role of coenzyme Q10 in statin-associated myopathy: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:2231–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hanai J, Cao P, Tanksale P, Imamura S, Koshimizu E, Zhao J, Kishi S, Yamashita M, Phillips PS, Sukhatme VP, Lecker SH. The muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1/MAFbx mediates statin-induced muscle toxicity. J Clin Invest 2007;117:3940–3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mallinson JE, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Sidaway J, Westwood FR, Greenhaff PL. Blunted Akt/FOXO signalling and activation of genes controlling atrophy and fuel use in statin myopathy. J Physiol 2009;587:219–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mallinson JE, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Glaves PD, Martin EA, Davies WJ, Westwood FR, Sidaway JE, Greenhaff P. Pharmacological activation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex reduces statin-mediated upregulation of FOXO gene targets and protects against statin myopathy in rodents. J Physiol 2012;590:6389–6402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Araki M, Maeda M, Motojima K. Hydrophobic statins induce autophagy and cell death in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells by depleting geranylgeranyl diphosphate. Eur J Pharmacol 2012;674:95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ghatak A, Faheem O, Thompson PD. The genetics of statin-induced myopathy. Atherosclerosis 2010;210:337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Curran J, Tang L, Roof SR, Velmurugan S, Millard A, Shonts S, Wang H, Santiago D, Ahmad U, Perryman M, Bers DM, Mohler PJ, Ziolo MT, Shannon TR. Nitric oxide-dependent activation of CaMKII increases diastolic sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release in cardiac myocytes in response to adrenergic stimulation. PLoS One 2014;9:e87495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Crane FL. Biochemical functions of coenzyme Q10. J Am Coll Nutr 2001;20:591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vladutiu GD, Simmons Z, Isackson PJ, Tarnopolsky M, Peltier WL, Barboi AC, Sripathi N, Wortmann RL, Phillips PS. Genetic risk factors associated with lipid-lowering drug-induced myopathies. Muscle Nerve 2006;34:153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Szendroedi J, Phielix E, Roden M. The role of mitochondria in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011;8:92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Szendroedi J, Schmid AI, Chmelik M, Toth C, Brehm A, Krssak M, Nowotny P, Wolzt M, Waldhäusl W, Roden M. Insulin-stimulated mitochondrial ATP synthesis occurs independently of intramyocellular lipid accumulation in well-controlled type 2 diabetic humans. PLoS Med 2007;4:e154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mikus CR, Boyle LJ, Borengasser SJ, Oberlin DJ, Naples SP, Fletcher J, Meers GM, Ruebel M, Laughlin MH, Dellsperger KC, Fadel PJ, Thyfault JP. Simvastatin impairs exercise training adaptations. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:709–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Obayashi H, Nezu Y, Yokota H, Kiyosawa N, Mori K, Maeda N, Tani Y, Manabe S, Sanbuissho A. Cerivastatin induces type-I fiber-, not type-II fiber-, predominant muscular toxicity in the young male F344 rats. J Toxicol Sci 2011;36:445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sidaway J, Wang Y, Marsden AM, Orton TC, Westwood FR, Azuma CT, Scott RC. Statin-induced myopathy in the rat: relationship between systemic exposure, muscle exposure and myopathy. Xenobiotica 2009;39:90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Madsen CS, Janovitz E, Zhang R, Nguyen-Tran V, Ryan CS, Yin X, Monshizadegan H, Chang M, D'Arienzo C, Scheer S, Setters R, Search D, Chen X, Zhuang S, Kunselman L, Peters A, Harrity T, Apedo A, Huang C, Cuff CA, Kowala MC, Blanar MA, Sun CQ, Robl JA, Stein PD. The guinea pig as a preclinical model for demonstrating the efficacy and safety of statins. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2008;324:576–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Naba H, Kakinuma C, Ohnishi S, Ogihara T. Improving effect of ethyl eicosapentanoate on statin-induced rhabdomyolysis in Eisai hyperbilirubinemic rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006;340:215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang P, Verity MA, Reue K. Lipin-1 regulates autophagy clearance and intersects with statin drug effects in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab 2014;20:267–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Limaye V, Bundell C, Hollingsworth P, Rojana-Udomsart A, Mastaglia F, Blumbergs P, Lester S. Clinical and genetic associations of autoantibodies to 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme a reductase in patients with immune-mediated myositis and necrotizing myopathy. Muscle Nerve 2014. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Knauer MJ, Urquhart BL, Meyer zu Schwabedissen HE, Schwarz UI, Lemke CJ, Leake BF, Kim RB, Tirona RG. Human skeletal muscle drug transporters determine local exposure and toxicity of statins. Circ Res 2010;106:297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rodrigues AC. Efflux and uptake transporters as determinants of statin response. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2010;6:621–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bersot T. Drug therapy for hypercholesterolemia and dyslipidemia. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011, p877–905. [Google Scholar]

- 109.DeGorter MK, Tirona RG, Schwarz UI, Choi YH, Dresser GK, Suskin N, Myers K, Zou G, Iwuchukwu O, Wei WQ, Wilke RA, Hegele RA, Kim RB. Clinical and pharmacogenetic predictors of circulating atorvastatin and rosuvastatin concentrations in routine clinical care. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2013;6:400–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gong IY, Kim RB. Impact of genetic variation in OATP transporters to drug disposition and response. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2013;28:4–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.SEARCH Collaborative Group Link E, Parish S, Armitage J, Bowman L, Heath S, Matsuda F, Gut I, Lathrop M, Collins R. SLCO1B1 variants and statin-induced myopathy--a genome wide study. N Engl J Med 2008;359:789–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vladutiu GD, Isackson PJ, Kaufman K, Harley JB, Cobb B, Christopher-Stine L, Wortmann RL. Genetic risk for malignant hyperthermia in non-anesthesia-induced myopathies. Molec Genet Metab 2011;104:167–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Vladutiu GD, Tarnopolsky M, Baker S, Christopher-Stine L, Peltier W, Weisman M, Isackson PJ. Inborn errors of muscle metabolism implicated in risk for statin-induced myopathy. Molec Genet Metab 2014;111:264–265. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Baker SK, Vladutiu GD, Peltier WL, Isackson PJ, Tarnopolsky MA. Metabolic myopathies discovered during investigations of statin myopathy. Can J Neurol Sci 2008;35:94–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ruaño G, Windemuth A, Wu AH, Kane JP, Malloy MJ, Pullinger CR, Kocherla M, Bogaard K, Gordon BR, Holford TR, Gupta A, Seip RL, Thompson PD. Mechanisms of statin-induced myalgia assessed by physiogenomic associations. Atherosclerosis 2011;218:451–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mangravite LM, Engelhardt BE, Medina MW, Smith JD, Brown CD, Chasman DI, Mecham BH, Howie B, Shim H, Naidoo D, Feng Q, Rieder MJ, Chen YD, Rotter JI, Ridker PM, Hopewell JC, Parish S, Armitage J, Collins R, Wilke RA, Nickerson DA, Stephens M, Krauss RM. A statin-dependent QTL for GATM expression is associated with statin-induced myopathy. Nature 2013;502:377–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Carr DF, Alfirevic A, Johnson R, Chinoy H, van Staa T, Pirmohamed M. GATM gene variants and statin myopathy risk. Nature 2014;513:E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Oh J, Ban MR, Miskie BA, Pollex RL, Hegele RA. Genetic determinants of statin intolerance. Lipids Health Dis 2007;6:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.De Vera MA, Bhole V, Burns LC, Lacaille D. Impact of statin adherence on cardiovascular disease and mortality outcomes: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;78:684–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]