Abstract

This qualitative, interview-based study assessed the cultural competence of health and social service providers to meet the needs of LGBT older adults in an urban neighborhood in Denver, Colorado, known to have a large LGBT community. Only 4 of the agencies were categorized as “high competency” while 12 were felt to be “seeking improvement” and 8 were considered “not aware.” These results indicate significant gaps in cultural competency for the majority of service providers. Social workers are well-suited to lead efforts directed at improving service provision and care competencies for the older LGBT community.

Keywords: LGBT, aging, qualitative research, service providers, cultural competence

INTRODUCTION

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons are at higher risk for health issues and face social and institutionalized barriers to accessing healthcare and social services as they age (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Emlet, Muraco, Erosheva, Hoy-Ellis, & Petry, 2011; Met Life, 2006). Related to these barriers, although older LGBT adults have disproportionately higher needs compared with their heterosexual counterparts (Cahill, South, Spade, 2000), older LGBT community members consistently report a lack of confidence in the “gay friendliness” of service providers, which likely contributes to their lower rates of service utilization (SAGE, 2010; Stein, Beckerman, & Sherman, 2010). This issue is not well understood and only recently has research been implemented to examine the factors associated with the lack of competence among social and health service providers when working with LGBT older adults. While efforts are underway to counter the lack of research on the LGBT aging population and to better integrate LGBT aging issues into related public policy (National Academy on an Aging Society, 2011), further research is needed to identify solutions regarding a lack of cultural competency among health and social service providers so that the needs of LGBT older adults can be appropriately addressed. The current study contributes to addressing this gap in the literature by investigating cultural competency of health and social service organizations serving LGBT older adults in one Denver, Colorado community.

LITERATURE REVIEW

There are an estimated 2–7 million older adults in the US who identify as LGBT; that is approximately 5–10% of the older adult population (Grant, 2010). Approximately 320,000 LGBT persons reside in Colorado, and Denver ranks 7th in the U.S. for percentage of LGBT households. In a 2011 survey (N=4,619) conducted by Colorado’s lead LGBT advocacy organization to learn more about the lives and issues faced by the state’s LGBT population, One Colorado Education Fund identified that about 15% (n=687) of the statewide LGBT respondents were 55 or older. When asked to identify the top five policy or social issues for LGBT people in Colorado, 52% identified increased support and services for LGBT older adults, and 42% ranked access to LGBT-welcoming healthcare. Thirty-five percent lived alone, 11% had caregiver duties for another adult or their partner, and 57% had no designated beneficiary agreement in Colorado. Thirty percent of respondents aged 65 or older (n=158) were not open about their sexual orientation/gender identity with their healthcare provider (One Colorado Education Fund, 2011).

Needs and Risks

LGBT older adults are identified as a group at risk for isolation (Addis et al., 2009; Wallace et al., 2011). Members of the LGBT community over the age of 50 are more likely to be single and live alone (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011). In addition, these individuals may be at higher risk of experiencing negative consequences of isolation because they are more than four times as likely as heterosexual older adults to be childless (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011). Caregiving support will likely be limited for many LGBT older adults, and LGBT persons providing care to a partner may face compounded risks related to reduced informal family supports in addition to fear of discrimination within the formal healthcare and legal systems (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Hoy-Ellis, 2007; Muraco & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2011). This factor has several health related implications:

Research suggests that social isolation can lead to a number of mental and physical ailments such as depression, delayed care-seeking, poor nutrition, and poverty—all factors that greatly lessen the quality of life for both LGBT older adults and elders of color. Living in isolation, and fearful of the discrimination they could encounter in mainstream aging settings, many marginalized elders are also at a higher risk for elder abuse, neglect, and various forms of exploitation. For LGBT elders of color, this social isolation might be intensified, since they might also be isolated from their racial and ethnic communities as LGBT older people and isolated from the mainstream LGBT community as people of color. (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011)

Although an initial understanding of the health needs and risks for LGBT older adults is underway, there is still much to learn. In 2011, the Institute of Medicine and National Institutes of Health (IOM) convened a group of experts to discuss ways to improve the limited evidence base on LGBT health. They put forth a research agenda focusing on demographics, social influences on health and health care inequities, interventions, and transgender-specific health needs (Institute of Medicine, 2011). This agenda directly relates to examining the quality of care LGBT older adults may receive; which in several ways is directly determined by the competence of the service providers. Additionally, The Joint Commission recently released a Field Guide for health and social service providers comprising a collation of approaches, practice examples, resources, and recommendations designed to support hospital staff in increasing quality of care by providing care that is more hospitable, safe, and inclusive of LGBT patients and families (The Joint Commission, 2011). Although there is a wealth of research related to cultural competence, there is a literature gap specific to competence of health and social service provision for LGBT older adults. These recent efforts by IOM and the Joint Commission are a response to this current gap in the research and practice.

Cultural Competence

Cultural competence in social work practice is multifaceted and comprised of a combination of factors including (Cooper & Lesser, 2008, p. 71):

Cultural literacy or the experience from immersion in another culture

Cross-cultural specific knowledge

Practitioner’s awareness of their own assumptions, values and beliefs

Willingness to learn and be comfortable with not being the expert in every culture

Importantly, when cultural competence is applied at an organizational rather than provider level, it involves policies and procedures that are flexible and considerate of the needs, fears, and preferences of disenfranchised groups that the organization serves.

Although cultural competency is an important value of professional social work, standards are not noticeably being pursued for LGBT older adults. Studies suggest there is a lack of culturally competent health and social services available for the older LGBT community nationwide. In many instances, social services sustain homophobic and heterosexist beliefs that provoke fear and anxiety in LGBT older adults when accessing services such as housing and healthcare (Cahill, South, & Spade, 2000; Coon, 2007). LGBT seniors are five times less likely to access available public and community services due to fear of discrimination or harm (SAGE, 2010; Stein, Beckerman, & Sherman, 2010).

LGBT older adults and their caregivers may be apprehensive of cultural competence deficiencies among health care providers (Brotman, Ryan, Collins, Chamberland, et al., 2007; MetLife Mature Market Institute, 2006). In an extensive review of the literature examining care seeking behavior of older LGBT individuals, Fredriksen-Goldsen and Muraco (2010) found that LGBT older adults are at increased risk of abstaining from needed care. A lack of access to care for this population has been established (Clark, Landers, Linde, & Sperber, 2001). Evidence suggests that fears experienced by LGBT seniors are warranted (Smedley, Stith, Nelson, 2003) and the need for improved competency of services provided to the LGBT aging population is clear (Meyer, 2011; Knochel, Quam, & Croghan, 2011). However, further examination of current cultural competencies of healthcare and social service providers is needed to understand best practices for intervention.

The purpose of this study was to explore the level of cultural competence of health and social service providers to ultimately improve services for LGBT older adults in an urban neighborhood of Denver, Colorado. The study was conducted by Seniors Using Supports To Age In Neighborhoods (SUSTAIN). This community-research partnership is comprised of aging service agencies, community-based organizations, health care systems and local universities whose purpose is to understand and begin to address health, social service, and community needs of LGBT older adults in this metropolitan Denver neighborhood. The SUSTAIN partners are members of the LGBT community or straight allies with strong connections to the LGBT aging community. The vision of the partnership is to create a community where LGBT seniors are able to age in a safe and trusting environment. This paper discusses findings from interviews conducted with service providers whose organizations address primary needs identified by the LGBT aging community. To better understand the level of cultural competence of local health and social service providers, the goals of this study were to: a) describe the services of local providers, b) better understand the consumers and staff characteristics of these organizations, and c) explore provider perceptions of LGBT older adults’ health and social needs.

METHOD

This investigation was a formative evaluation using rapid assessment techniques emphasizing a team-oriented, participatory action, and time-sensitive approach to generate information related to service provision for LGBT older adults (Beebe, 2013; Padgett, 2012; WHO, 2004). Rapid assessment is commonly used to design culturally appropriate interventions for health and social problems, by focusing on local knowledge about these issues. Rapid assessment is time efficient, team-based ethnographic approach to qualitative inquiry that can quickly develop a preliminary understanding of a problem or situation (Beebe, 2013). As a team, the SUSTAIN partnership conducted interviews with local social service, health, and faith-based organizations. All study related procedures were approved by the Kaiser Permanente Colorado Institutional Review Board.

Recruitment

A convenience sample of local neighborhood providers was selected from a comprehensive list of providers. This list of 110 organizations was created by researching all social service, health, and faith-based providers in the geographic area, and was then organized into service categories defined by the partnership, including: legal, benefit assistance, mental health, transportation, housing, aging specific, faith-based, home services, political, senior engagement, and end of life care. The list was then reviewed by SUSTAIN partners to select 2–3 organizations per category to provide a broad variety of service types for interviews. With the intent to interview 30 organizations, 43 potential interview participants were initially selected based upon the following criteria: a) unknown to the SUSTAIN partnership to be LGBT competent, and b) provided a specific service to older adults in the Denver neighborhood under investigation. SUSTAIN participating organizations and agencies known to the partnership as particularly LGBT-friendly were excluded from participation. With the intent to interview 30 providers, the list was then distributed across six SUSTAIN partners from various organizations for the recruitment of interviewees, each responsible for the recruitment of 5 participants. Thirty potential provider participants were contacted by these SUSTAIN partners via telephone and email, however, only 29 providers completed the interview.

Interviews

The interviews were completed by the six SUSTAIN partners over the phone or in-person based on the providers’ preference. All of the evaluators were trained interviewers with backgrounds in either clinical or research interview techniques. To prepare for data collection, the interviewers conducted mock interviews with fellow SUSTAIN partners. Prior to the interview, participants were given an informed consent document and oral consent was obtained. The interviews were structured in format, meaning a standardized sequence of questions was utilized to increase reliability across interviewers (Patton, 1991), and were approximately 30–90 minutes in length. While interviews were audio recorded to ensure accuracy in interpretation, due to the time sensitive nature of rapid assessment, field notes, rather than transcription were utilized for data analysis. Field notes were first taken during the interviews, and were later confirmed and detailed by the interviewer when reviewing the audio recordings.

The interview guide was created collaboratively by the SUSTAIN partners. Questions were derived from SUSTIAN’s previous community member needs assessment which is currently under review for publication elsewhere. Questions inquired about consumer and staff characteristics, service provision, and LGBT cultural competency (Table 1). Specifically pertaining to competency, these questions highlighted organizations’ awareness of the aging LGBT population served, friendliness of these services to older LGBT adults, and understanding of LGBT older adults’ needs. Although structured in nature, the interview guide allowed the flexibility for elaboration and probing if needed.

Table 1.

Interview Guide Summary

| Consumers and Staff |

| How would you describe your clients? |

| Do you have a sense of what percentage might be LGBT? What about staff? |

| What is the age range of LGBT clients? |

| What lets you know that your clients/staff are LGBT? |

| Does your employee benefits package equally recognize straight and LGBT partnerships? |

| Services |

| Have you thought about how welcoming your services are for LGBT older adults? |

| How would an older LGBT person know that you are welcoming? |

| Does your mission statement, intake form or marketing materials reflect that you are welcoming to the LGBT community? |

| Have you made any specific changes in your business to better serve the LGBT community? |

| How do you train your employees to be welcoming? |

| Serving LGBT Older Adults |

| What unique knowledge, skills or qualities do you feel you need to serve the LGBT community? |

| How do you keep yourself informed on LGBT community events and information? |

Analysis

Completed interview guides and field notes were compiled for all interviews and analyzed by research assistants at Kaiser Permanente Colorado to identify key topics related to consumer and staff characteristics, services, and cultural competency. Specifically, two cycles of coding were carried out to develop final results. Structure coding, which is used to identify specific areas of inquiry, and process coding, which identifies ongoing action in response to problematic situations were first used to code based on the structured question areas and ongoing actions of agencies (Saldana, 2009). The second cycle of coding employed focused coding in which the most significant initial codes are developed into salient categories (Saldana, 2009).

Through the coding process, agencies were classified into categories based on their service type and job responsibilities to describe characteristics and services of the local providers. To better understand their consumer and staff characteristics, providers were also categorized based on the percentage of LGBT consumers and staff they described during the interviews. Agencies typically reported a specific percentage estimate, which were organized into categories decided by the partnership which ranged from high (more than 70%) to medium (15–60%) to low (5% or less). None of the agencies identified having between 5–15% percent of LGBT consumers or staff, so this level was not included as a category. Providers that were unable to offer an estimate were labeled “unknown” or “no idea”, and providers who specifically stated the majority of their consumers were straight were assigned to the “mostly straight” category.

Focused codes were then used to explore provider perceptions about LGBT older adults’ needs and providers’ level of cultural competency. When discussing LGBT cultural competencies, three levels of proficiency were identified (Table 2); based on interview responses, agencies were categorized using this proficiency continuum. These categories emerged from the data, as organizations provided information and examples of their understanding, awareness, and targeted services for older LGBT adults. These qualitative categories, which ranged from high competence, or agencies demonstrating high levels of awareness for LGBT older adults, to low competence, labeled “not aware”, for organizations representing little understanding or appreciation for the needs of LGBT older adults, were used to measure the level of competency among the interviewed organizations. The level of cultural competency was then examined by agency type, service provision, percentage of LGBT consumers, and percentage of LGBT staff.

Table 2.

Level of Cultural Competency Focus Code and Description

| Focus Code | Description/Definition |

|---|---|

| High Competence | Service provider demonstrated understanding of LGBT aging issues and implemented services appropriately. These agencies explained how older LGBT adults would know services were welcoming; used appropriate materials; made changes to better serve the LGBT community; and stayed informed on LGBT issues. |

| Seeking Improvement | Service provider recognized the need for improving services to meet needs of LGBT older adults |

| Not Aware | Service provider stressed being “inclusive” but disregarded need for specific LGBT cultural competencies |

To maintain rigor throughout the analysis process the research assistants met regularly to discuss any challenges or inconsistencies in coding. Memos were recorded throughout the analysis process to document decision making. Coding results were presented to the partnership ongoing to gain feedback and insight from experts and community partners. It is also important to note partnership presuppositions. Specifically, although SUSTAIN felt that a range of competence levels would be identified, some partners speculated that competency would be lower among faith-based organizations. No other a priori assumptions were identified by the partnership.

RESULTS

Participants

Interviewees were typically executive managers (n=13), but program coordinators (n=7) were also commonly interviewed. Most service providers were social service organizations, health providers, or both. However, faith-based, business, and mental health providers were also interviewed. While some of the organizations identified as a non-profit (n=6) or for-profit agency (n=4), the majority of interviewees did not specify their non-profit status (n=19). Providers offered a variety of programming for older LGBT adults, including: individual and direct services, community development, network collaboration, advocacy and public policy, outreach and education, and research services. Table 3 summarizes the provider characteristics.

Table 3.

Service Provider Characteristics

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Profit Status | |

| Non-Profit | 6 (20) |

| For-Profit | 4 (15) |

| Unknown | 19 (65) |

| Service Categoriesa | |

| Social Service | 13 (45) |

| Health | 9 (31) |

| Spiritual/Religious | 3 (10) |

| Legal/Business | 3(10) |

| Mental Health | 2 (7) |

Categories are not mutually exclusive.

Consumer and Staff Characteristics

Capturing the number of LGBT older adults receiving services was difficult, with 44% of all providers responding that they did not know the proportion of their consumers who were LGBT (Table 4). Agencies often did not inquire about sexual orientation due to anti-discrimination laws. Only three agencies asked about sexual orientation, although none of these providers tracked the information. Self-disclosure and self-identification were the most common ways of knowing the estimated number of LGBT individuals served by the agency. Organizations who identified higher rates of LGBT consumers of all ages often attributed their answer to the type of work in which the provider specialized (e.g. HIV case management services), the location of the agency within the specific neighborhood, or a strong referral system with LGBT specific organizations. While most agencies did not know the number of LGBT staff, regardless of age, many organizations provided staff with same-sex partner benefits. However, some agencies did not provide benefits to same-sex partners, and two required proof of marriage for benefit provision.

Table 4.

Service Provider Estimates of LGBT Consumers and Staff

| Percent of Clients | N (%) |

| High (>70%) | 4 (14) |

| Medium (15–60%) | 4 (14) |

| Low (5%) | 6 (21) |

| “Mostly Straight” | 2 (7) |

| Unknown/”No Idea” | 13 (44) |

| Percent of Staff | N (%) |

| High (>70%) | 2 (3) |

| Medium (15–60%) | 5 (17) |

| Low (5%, #) | 6 (21) |

| Unknown | 16 (56) |

Serving LGBT Older Adults

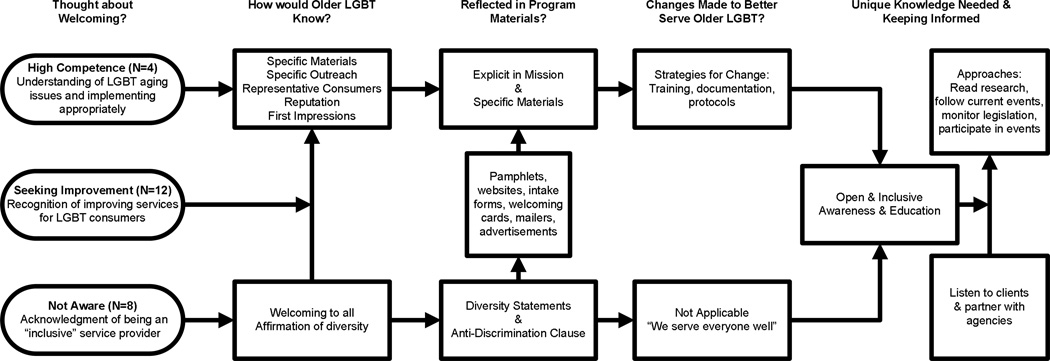

The thematic framework describing agency cultural competency processes is illustrated in Figure 1. Only a few organizations (n=4) were considered proficient in their awareness, understanding, and actions to appropriately serve LGBT older adults. Labeled the “high competence” group, these providers were clearly able to explain how older LGBT adults would know their services were welcoming, used appropriate materials, made changes to better serve the LGBT community, and stayed informed regarding LGBT issues. The “high competence” group expressed a strong understanding of LGBT aging issues and was implementing strategies appropriately to address important needs. As such, these organizations used specific materials and outreach efforts for LGBT older adults and marketed themselves effectively to maintain a “welcoming” reputation. In addition to specific materials, some of these organizations included explicit statements about being open to the LGBT population in their mission statement. Because these agencies felt it was important to meet these individualized needs, they were either currently or in the process of adopting strategies, such as training and documentation protocols, to improve the competence and inclusivity of their agency. These were the same agencies that specifically followed current research, monitored legislation, and participated in events related to LGBT issues.

Figure 1.

Thematic framework.

Most organizations (n=12) were “seeking improvement.” These providers used only a few welcoming practices and, during the interview, most recognized several areas in need of improvement. The organizations classified as “not aware” (n=8) stressed being inclusive but disregarded that LGBT older adults have distinct needs. The providers reported that they were welcoming to all diverse groups and stressed the use of diversity statements and anti-discrimination clauses within organization materials. The “not aware” group did not see a reason to make changes to their current practices and expressed that all persons were treated fairly and the same, regardless of specific characteristics.

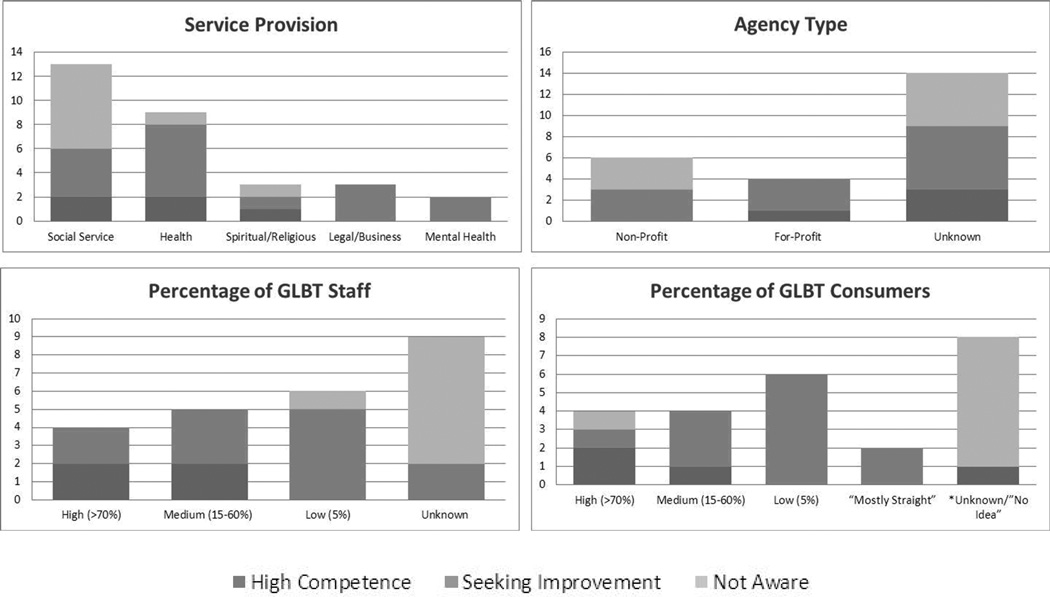

Competency by agency type, service provision and percentage of LGBT consumers and staff varied. Half of the non-profit organizations were classified as “seeking improvement” while the other half were “not aware,” whereas the majority of for-profit organizations were classified as “seeking improvement.” The largest grouping of “not aware” was among unknown non-profit status organizations. Seven social service agencies and only one health agency were identified as “not aware,” while all mental health and legal/business providers were “seeking improvement.” The three spiritual/religious organizations interviewed were represented across all three levels of competency. The majority of providers who were unable to provide an estimate of LGBT consumers (n=9 agencies) and staff (n=7 agencies) were considered “not aware,” however one agency specifying a high number of LGBT consumers was also classified as “not aware.”

DISCUSSION

This interview-based study of service providers for older adults in a metropolitan area of Denver known to have a large LGBT community revealed a broad spectrum of services and practices. Few participating agencies were categorized as having “high competence” to address the needs of LGBT older adults. Similar findings have been presented for aging network services in Michigan, revealing a lack of services specific to LGBT older adults and little outreach to this population (Hughes, Harold and Boyer, 2011). However, regardless of competency classification, all providers interviewed expressed interest in partnering with SUSTAIN in ongoing work to address health and social service barriers. Thus, our results indicate a role for social work practitioners in increasing awareness of and education about culturally competent and sensitive service provision for the aging LGBT community.

The findings from these data and conversations with community stakeholders and policy makers have confirmed that the majority of organizations lack appropriate focus on the specific needs of the LGBT aging population. Social workers, whether they are community or clinical practitioners, are uniquely suited to work with communities and providers to ensure that culturally competent services are available. A few topic areas that social workers can hone their focus of practice are worth mentioning here. First, navigating and coaching older adults to identify LGBT-friendly providers is a role that social workers should seek out. As those most often providing case management services aimed at keeping older adults in their homes and maintaining independence, social workers can advocate that services be modified in a way to attend to the unique needs of LGBT older adults. Social workers can collaborate with provider agencies to identify ways to increase socialization and decrease isolation for this vulnerable population. Social workers can also work with communities to identify unique health and social service priorities based on neighborhood assessments and recommend subsequent interventions. For example, recommending competency training for providers who lack cultural proficiency for LGBT older adults.

Training provided to area agencies on aging (aging network organizations) around LGBT aging issues is limited. However, agencies with such training are significantly more likely to have services and outreach to the older LGBT community (Knochel, Croghan, Moone, & Quam, 2012). Therefore, LGBT aging curricula must first be available to social work students. This topic might best be suited for diversity or aging practice courses. Recent research suggests that LGBT aging training should provide useful and valuable information, a safe enviornment for deeper understanding and self-relflection, and incorpeate older LGBT instructors (Rogers, Rebbe, Gardella, Worlein, & Chamberlin, 2013).

Project Visibility is one example of a group that has received local as well as national accolades for providing LGBT aging specific cultural education to nursing homes, assisted livings, home care agencies and other senior service agencies in Colorado. Project Visibility highlights the fears of “going back in the closet” and “being invisible” when LGBT older adults have to go to a nursing home or assisted living situation (Project Visability, n.d.). Even with this wonderful resource available locally, we found many local agencies stuck in the “treat everybody the same” mindset are unlikely to be open to these education opportunities. Social workers can increase organizations’ awareness of LGBT older adult consumers, identify inadequate services, advocate for openly LGBT employees, and utilize welcoming marketing materials.

Many of the providers interviewed could not specify the sexual orientation of their client population. When agencies are unaware of the populations they serve, they are also likely to be unfamiliar with the specialized needs of diverse and vulnerable populations. Anti-discrimination policies restricted providers from inquiring about sexual minority status, and LGBT older adults are unlikely to disclose this information (Colorado One Education Fund, 2011, SAGE, 2010; Stein, Beckerman, & Sherman, 2010); however, agency level policies can be put in place to enhance the provision of individualized competent services. Specifically, policies and procedures that are flexible and considerate of the needs, fears, and preferences of disenfranchised groups that the organization serves (Cooper & Lesser, 2008). However, Hughes, Harold and Boyer, 2011 identified an agency-level resistance to provide LGBT specific services to aging adults. Addressing the reluctance of health and social service agencies to increase awareness of the expanding LGBT aging population and discomfort with LGBT issues must be addressed.

As an initial step towards providing culturally competent services for LGBT older adults, social workers must address issues of LGBT older adults’ awareness of their services by improving the welcoming nature of the organization and ensuring the acceptability and accessibility of their services to LGBT older adults. Overall, there are several recommendations for macro social work practitioners that can serve as a guide for the provision of culturally competent services for LGBT older adults, including (Coon, 2003; The Joint Commission, 2011; Lee and Quam, 2013; SAGE, 2010): (a) provide LGBT older adult competency training, (b) develop and adopt LGBT aging specific non-discrimination policies, (c) collaborate with aging and LGBT supportive organizations to develop improved service standards, (d) increase onsite LGBT older adult specific services, and (e) improve opportunities for LGBT older adults to engage in services, such as volunteering and equal employment, and participate in decision making processes relevant to LGBT older adults’ needs.

In addition to improvements in macro practice, clinical social workers can develop cultural competencies for older LGBT adults through the use of reflective practice to learn about their lives and concerns (Lee & Quam, 2013). Social workers should first adopt an LGBT-affirming attitude, avoiding assumptions about sexual orientation and gender identity, and working within the spectrum of “openness” (Concannon, 2007; The Joint Commission, 2011). Use of open-ended and gender-neutral language in assessment questions, forms and when speaking with consumers is essential, as is listening to individual descriptions of sexual orientation, relationships, and partnership (Concannon, 2007; Coon, 2003; The Joint Commission, 2011). By providing informed, open-minded and supportive care, social workers are likely to offer enhanced culturally competent services for LGBT older adults.

Several study limitations should be acknowledged. First, the list of local aging service providers developed by the SUSTAIN partnership was meant to be highly representative but not comprehensive, and the final choice of providers interviewed was determined by convenience rather than random selection. This study was also limited to a specific region of a metropolitan area that has unique demographic characteristics that may influence the types of providers serving the area and thus may impact generalizability. However, it should be noted that this community was targeted due to a higher percentage of LGBT persons suggesting that our findings could represent a “best case” scenario for a high likelihood of cultural competency. Finally, the number of LGBT older adults actually receiving services through these local agencies remains poorly captured.

Overall, while some providers demonstrated high levels of competency and welcoming strategies, most providers need assistance in improving service provision for LGBT older adults. Further research exploring the specialized needs of this population is required to inform best practices with LGBT older adults. Social workers should collaborate with health and social service agencies and at-risk communities to enhance welcoming and sensitive services through awareness and education efforts.

Figure 2.

LGBT cultural compentency by service provider characteristics. Due to the small sample size the frequency (n) was provided for each category. Service provision are not a mutually exclusive categories.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of additional SUSTAIN community partners: Debra Angell, Carlos Martinez, Rene Hickman, and William Lundgren. This work was supported by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000154. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Dickman Portz, Institute for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Denver, Colorado, USA, Graduate School of Social Work, University of Denver, Denver, Colorado, USA, and School of Social Work, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Jessica H. Retrum, Department of Social Work, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Denver, Colorado, USA and School of Public Affairs, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado, USA

Leslie A. Wright, Institute for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Denver, Colorado, USA

Jennifer M. Boggs, Institute for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Denver, Colorado, USA

Shari Wilkins, The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center of Colorado, Denver, Colorado, USA.

Cathy Grimm, Jewish Family Service, Denver, Colorado, USA.

Kay Gilchrist, Services and Advocacy for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual & Transgender Elders (SAGE) of the Rockies Committee, Denver, Colorado, USA.

Wendolyn S. Gozansky, Institute for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Denver, Colorado, USA

References

- Addis S, Davies M, Greene G, MacBride Stewart S, Shepherd M. The health, social care and housing needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender older people: A review of the literature. Health & social care in the community. 2009;17(6):647–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe J. Rapid assessment process. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.rapidassessment.net/ [Google Scholar]

- Brotman S, Ryan B, Collins S, Chamberland L, Cormier R, Julien D, Richard B. Coming out to care: Caregivers of gay and lesbian seniors in Canada. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(4):490–503. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.4.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill S, South K, Spade J. Outing age: Public policy issues affecting gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender elders. The Policy Institute of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Foundation. 2000 Retrieved from http://www.thetaskforce.org/downloads/reports/reports/OutingAge.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Clark ME, Landers S, Linde R, Sperber J. The GLBT Health Access Project: a state-funded effort to improve access to care. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):895–896. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concannon L. Developing Inclusive Health and Social Care Policies for Older LGBT Citizens. British Journal of Social Work. 2007;39(3):403–417. [Google Scholar]

- Coon DW. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) issues and family caregiving. San Francisco, CA: Family Caregiver Alliance, National Center on Caregiving; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Coon DW. Exploring interventions for LGBT caregivers. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2007;18(3):109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MG, Lesser JG. Clinical social work practice: an integrated approach. Boston, MA: Pearson Education; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Hoy-Ellis CP. Caregiving with pride. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2007;18(3–4):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Muraco A, Mincer S. Chronically ill midlife and older lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals and their informal caregivers: The impact of the social context. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2009;6(4):52–64. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2009.6.4.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Muraco A. Aging and sexual orientation: A 25-year review of the literature. Research on Aging. 2010;32(3):372–413. doi: 10.1177/0164027509360355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Emlet CA, Muraco A, Erosheva EA, Hoy-Ellis, & Petry H. The aging and health report: Disparities and resilience among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Institute for Multigenerational Health. 2011 Retrieved from http://caringandaging.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Full-Report-FINAL-11-16-11.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Grant JM. Outing age: Public policy issues affecting gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender elders. The Policy Institute of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Foundation. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.thetaskforce.org/downloads/reports/reports/outingage_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AK, Harold RD, Boyer JM. Awareness of LGBT aging issues among aging servies network providers. Gerotological Social Work. 2011;54(7):659–677. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2011.585392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/The-Health-of-Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-and-Transgender-People.aspx. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knochel KA, Croghan CF, Moone RP, Quam JK. Training, Geography, and Provision of Aging Services to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Older Adults. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2012;55(5):426–443. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2012.665158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knochel KA, Quam JK, Croghan CF. Are old lesbian and gay people well served? Understanding the perceptions, preparation, and experiences of aging services providers. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2011;30(3):370–389. [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Quam JK. Comparing Supports for LGBT Aging in Rural Versus Urban Areas. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2013;56(2):112–126. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2012.747580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MetLife Mature Market Institute. Out and aging: The MetLife study of lesbian and gay baby boomers. 2006 Retrieved from https://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/studies/mmi-out-aging-lesbian-gay-retirement.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer H. Safe spaces? The need for LGBT Cultural Competency in Aging Services. Public Policy & Aging Report. 2011;24 [Google Scholar]

- Muraco A, Fredriksen-Goldsen K. “That’s what friends do”: Informal caregiving for chronically ill midlife and older lesbian, gay, bisexual adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2011;28(8):1073–1092. doi: 10.1177/0265407511402419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academy on an Aging Society. Public policy & aging report: Integrating lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults into aging policy and practice. In: Hudson RB, editor. National Academy on an Aging Society. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- One Colorado Education Fund. Invisible: The state of LGBT health in Colorado. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.one-colorado.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/OneColorado_HealthSurveyResults.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK. Qualitative and mixed methods in public health. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Project Visability. Training schedule and information. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.bouldercounty.org/family/seniors/pages/projvis.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers A, Rebbe R, Gardella C, Worlein M, Chamberlin M. Older LGBT adult training panels: An opportunity to educate about issues faced by the older LGBT community. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2013 doi: 10.1080/01634372.2013.811710. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Service and Advocacy for GLBT Elders (SAGE) Movement advancement project and services and advocacy for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender elders. Retrieved from http://www.lgbtmap.org/policy-and-issue-analysis/improving-the-lives-of-lgbt-older-adults. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankle MD, Maxwell CA, Katzman ES, Landers S. An invisible population: older lesbian gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. Clinical Research and Regulatory Affairs. 2003;20(2):159–182. [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, Beckerman NL, Sherman PA. Lesbian and gay elders and long-term care: Identifying the unique psychosocial perspectives and challenges. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2010;53(5):421–435. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2010.496478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient-and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A Field Guide. 2011 Retrieved from: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/LGBTFieldGuide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace SP, Cochran SD, Durazo EM, Ford CL. The Health of Aging Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Adults in California. UC Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) A guide to rapid assessment of human resources for health. 2004 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hrh/tools/en/Rapid_Assessment_guide.pdf.