Abstract

Plant hormone auxin regulates most, if not all aspects of plant growth and development, including lateral root formation, organ pattering, apical dominance, and tropisms. Peptide hormones are peptides with hormone activities. Some of the functions of peptide hormones in regulating plant growth and development are similar to that of auxin, however, the relationship between auxin and peptide hormones remains largely unknown. Here we report the identification of OsCLE48, a rice (Oryza sativa) CLE (CLAVATA3/ENDOSPERM SURROUNDING REGION) gene, as an auxin response gene, and the functional characterization of OsCLE48 in Arabidopsis and rice. OsCLE48 encodes a CLE peptide hormone that is similar to Arabidopsis CLEs. RT-PCR analysis showed that OsCLE48 was induced by exogenously application of IAA (indole-3-acetic acid), a naturally occurred auxin. Expression of integrated OsCLE48p:GUS reporter gene in transgenic Arabidopsis plants was also induced by exogenously IAA treatment. These results indicate that OsCLE48 is an auxin responsive gene. Histochemical staining showed that GUS activity was detected in all the tissue and organs of the OsCLE48p:GUS transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Expression of OsCLE48 under the control of the 35S promoter in Arabidopsis inhibited shoot apical meristem development. Expression of OsCLE48 under the control of the CLV3 native regulatory elements almost completely complemented clv3-2 mutant phenotypes, suggesting that OsCLE48 is functionally similar to CLV3. On the other hand, expression of OsCLE48 under the control of the 35S promoter in Arabidopsis has little, if any effects on root apical meristem development, and transgenic rice plants overexpressing OsCLE48 are morphologically indistinguishable from wild type plants, suggesting that the functions of some CLE peptides may not be fully conserved in Arabidopsis and rice. Taken together, our results showed that OsCLE48 is an auxin responsive peptide hormone gene, and it regulates shoot apical meristem development when expressed in Arabidopsis.

Keywords: auxin, peptide hormone, OsCLE48, CLV3, apical meristem, Arabidopsis, Oryza sativa

Introduction

Auxin regulates many aspects of plant growth and development, including apical dominance, organ formation, lateral root formation, root and stem elongation, and vascular development (Davies, 1995). It is very likely that auxin regulated plant growth and development is initiated by the activation of auxin response genes by locally increased auxin concentration (Chapman and Estelle, 2009).

Activation of auxin response genes is controlled by two different groups of transcription factors, auxin response factors (ARFs) and Aux/IAA proteins. When the cellular auxin level is low, Aux/IAA proteins are dimmerized with ARFs, thus inhibit the expression of auxin response genes. When the auxin level is elevated, auxin binds to TIR1 auxin receptor, leading to the activation of TIR1, and eventually the degradation of Aux/IAA proteins by 26S proteasome, result in the activation of auxin response genes by ARFs (Dharmasiri et al., 2005; Kepinski and Leyser, 2005; Guilfoyle and Hagen, 2007; Tan et al., 2007; Hayashi, 2012).

Several different gene families including Aux/IAAs, GH3s, and SAURs have been identified as auxin response genes (Hagen and Guilfoyle, 2002). Expression of some other genes such as ASL/LBD (LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN/ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2-LIKE) is also induced by auxin (Lee et al., 2009; Coudert et al., 2013). However, considering that auxin regulates almost every aspect of plant growth and development, it is likely that large numbers of auxin response genes remain unidentified (Kieffer et al., 2010).

Peptide hormones are peptides with hormone activities. Peptide hormones regulate many cellular processes in animals, bacteria and yeast (Edlund and Jessell, 1999). It has been believed that plants do not produce peptide hormones, until the identification of Systemin, a 18 amino acids peptide, as a signal molecule in wounding response in tomato (Pearce et al., 1991). So far nearly 20 plant peptide hormones have been identified (Germain et al., 2006; Hashimoto et al., 2008; Katsir et al., 2011; Leasure and He, 2012).

Plant peptide hormones are encoded by genes with small open reading frames (ORFs), and can be classified into two different groups: secreted and non-secreted peptide hormones (Hashimoto et al., 2008; Katsir et al., 2011; Matsubayashi, 2011). Precursors of secreted peptide hormones contain an N-terminal signal peptide, which facilities protein transport and will be removed during post-transcriptional modifications. On the other hand, non-secreted peptide hormones do not contain signal peptides (Hashimoto et al., 2008; Katsir et al., 2011; Matsubayashi, 2011).

Non-secreted plant peptide hormones include Systemin, Enod40 (Early Nodulin 40), POLARIS (PLS), ROT FOUR LIKE (RTFL), amd BRICK1 (BRK1; Charon et al., 1997; Germain et al., 2006; Hashimoto et al., 2008). Non-secreted peptide hormones are involved in the regulation of plant growth and development, and plant response to enviromental stresses. For example, PLS regulates root growth and vascular development (Casson et al., 2002), RTFL peptides DEVIL (DVL1) and ROTUNDIFOLIA4 (ROT4) regulate leaf and fruit development (Narita et al., 2004; Wen et al., 2004), IDL peptides regulate floral organ abscission (Butenko et al., 2003; Cho et al., 2008; Stenvik et al., 2008), and Systemin invloves in the regulation of plant stress response (Pearce et al., 1991, 2001; Constabel et al., 1998).

More than 10 different secreted peptide hormones have been identified in plants, including CLAVATA3/ENDOSPERM SURROUNDING REGION (CLE), EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR (EPF), ROOT MERISTEM GROWTH FACTOR (RGF)/CLE LIKE (CLEL)/GOLVEN (GLV), INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION LIKE (IDL), and RAPID ALKALINISATION FACTOR (RALF). Secreted peptide hormones are mainly involved in the regulation of plant growth and development. For example, CLE peptides are involved in the regulation of shoot and root apical meristem (SAM and RAM) mataining (Kinoshita et al., 2007; Jun et al., 2010; Katsir et al., 2011), RGF/CLEL/GLV peptides regulate root growth and lateral root formation (Matsuzaki et al., 2010; Meng et al., 2012a; Fernandez et al., 2013), and EPF peptides regulate stomata development (Hara et al., 2007; Hunt and Gray, 2009; Sugano et al., 2010). Most of the secreted peptide hormones are encoded by gene families. In Arabidopsis, for example, there are 32 genes encoding CLE peptides, 11 encoding RGF/CLEL/GLV peptides, and six encoding IDL peptides (Sawa et al., 2008; Stenvik et al., 2008; Matsuzaki et al., 2010; Meng et al., 2012a).

Very limited experimental evidence has shown that there is cross-talk between auxin and some of the peptide hormones. For example, PLS and RGF/CLEL/GLV peptides have been shown to regulate auxin transport, and the expression of PLS and RGF/CLEL/GLV genes are regulated by auxin (Casson et al., 2002; Chilley et al., 2006; Meng et al., 2012b; Whitford et al., 2012). On the other hand, auxin has been shown to involve in CLE-induced vascular proliferation (Whitford et al., 2008). In this study, we report the identification of OsCLE48, a rice CLE gene as an auxin response gene, and the functional characterization of OsCLE48 in Arabidopsis and rice.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis) ecotype Columbia (Col-0) and Japonica rice (Oryza sativa) variety Nipponbare were used for plant transformation. Arabidopsis mutant clv3-2 is in the ecotype Landsberg erecta (Ler) background (Clark et al., 1995).

Rice seeds were germinated and grown on water for 10 days. Seedlings were then transferred into soil pots and kept in a growth room. Arabidopsis seeds were sterilized and grown on plates containing ½ MS (Murashige and Skoog) medium with vitamins (PlantMedia) and 1% (w/v) sucrose, solidified with 0.6% (w/v) phytoagar (PlantMedia). Seedlings were transferred into soil pots and kept in a growth room. For plant transformation and phenotypic analysis of adult plants, Arabidopsis seeds were sown directly into soil and grown in a growth room. Arabidopsis plants were grown at 20°C, and rice plants at 28°C, with a 16 h light/8 h darkness photoperiod.

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNA from rice was isolated following the procedure described previously for RNA isolation from poplar (Geraldes et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014). Total RNA from Arabidopsis was isolated using the EazyPure Plant RNA Kit (TransGen Biotech) following the manufacturer’s procedure. cDNA was synthesized using the EazyScript First-Strand DNA Synthesis Super Mix (TransGen Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-PCR or quantitative RT-PCR was used to examine the expression of corresponding genes. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on a StepOne Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) with StepOne Software v2.1. All reactions were performed in three replications. Expression of Arabidopsis gene ACTIN2 (ACT2) or rice gene OsACT2 was used as control for RT-PCR. Rice gene UBQ5 (Jain et al., 2006) was used as control reference gene for quantitative RT-PCR.

All primers used in this study including primers for gene cloning and primers for gene expression analysis were listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of primers used in this study.

| Primers | Sequences |

|---|---|

| OsCLE48-Nde1F | 5′-CAACATATGGCGAAGGCGAAGGTTAGC-3′ |

| OsCLE48-Sac1R | 5′-CAAGAGCTCTCAGTGATGCTGAGGGTCTGGAC-3′ |

| OsCLE48-qPCRF | 5′-TCCTGCTGATTCTCTCGTACT-3′ |

| OsCLE48-qPCRR | 5′-TCGTCTCCTCTCGCATTATCT-3′ |

| UBQ5-qPCRF | 5′-ACCACTTCGACCGCCACTACT-3′ |

| UBQ5-qPCRR | 5′-ACGCCTAAGCCTGCTGGTT-3′ |

| OsCLE48p-Pst1F | 5′-CAACTGCAGTTCAAACCGAAATTACGTTC-3′ |

| OsCLE48p-Nco1R | 5′-CAACCATGGCCTAGGAAAAACCAAGAGCTC-3′ |

| WUS-Nde1F | 5′-CAACATATGGAGCCGCCACAGCATCAGC-3′ |

| WUS-Sac1R | 5′-CAAGAGCTCTAGTTCAGACGTAGCTCAAG-3′ |

| CLV3-5′sequence-Pst1F | 5′ -CAACTGCAGCCGGATTATCCATAATAAAAAC-3′ |

| CLV3-5′sequence-Nde1R | 5′ -CCCCCATATGAGAGAAAGTGACTGAGTGAG-3′ |

| CLV3-3′sequence-Sac1F | 5′ -AAAAGAGCTCCCTAATCTCTTGTTGCTTTAA-3′ |

| CLV3-3′sequence-EcoR1R | 5′ -CCCCGAATTCTATGTGTGTTTTTTCTAAACAA-3′ |

| OsACT2-F | 5′-TGTATGCCAGTGGTCGTACCAC-3′ |

| OsACT2-R | 5′-GAGATGCCAAGATGGATCCTCC-3′ |

| ACT2-F | 5′-ATGGATTCGAAGAGTTTTCTG-3′ |

| ACT2-R | 5′-TCAAGGGAGCTGAAAGTTGTTTC-3′ |

Constructs

To generate HA tagged OsCLE48 construct for plant transformation, the 252 bp full-length ORF of OsCLE48 was amplified by RT-PCR using RNA isolated from 10-days-old rice seedlings, and cloned in frame with an N-terminal HA tag into the pUC19 vector under the control of the double 35S enhancer promoter of CaMV. The pUC19OsCLE48 construct generated was then digested with proper enzymes, and subcloned into vector pPZP211 and pCAMBIA1301 to generate binary vector pPZP211OsCLE48 and pCAMBIA1301OsCLE48 for Arabidopsis and rice transformation, respectively.

To generate the OsCLE48p-GUS construct, a fragment that covers the region -1509 to +1 of the start codon of the OsCLE48 gene was amplified using DNA isolated from rice seedling as template, the PCR products was then used to replace the PtrCesA8 promoter in the PtrCesA8p-GUS construct (Wang et al., 2014). To generate the CLV3p-OsCLE48 construct, the 35S promoter and the nos terminator in the pUC19OsCLE48 construct was replaced respectively, by the 1.5-kb 5′ upstream and the 1.2-kb 3′ downstream regulatory sequences of CLV3 (Brand et al., 2002). Corresponding constructs in pUC19 were then digested with proper enzymes, and subcloned into pPZP211 vector for Arabidopsis transformation.

Plant Transformation

About 5-weeks-old Arabidopsis plants with several mature flowers on the main inflorescence were used for plant transformation. The transformation was conducted via Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GV3101) by using the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Phenotypes of transgenic plants were examined in the T1 generation, and confirmed in the following 2–4 generations. For all the transformation, more than five transgenic lines with similar phenotypes were obtained, and at least two lines were used for phenotypic analysis.

Rice transgenic plants were generated by using tissue culture and Agrobacterium tumefaciens co-cultivation methods (Hiei et al., 1994).

Auxin Treatment

To examine the expression of OsCLE48 in response to auxin, 10-days-old rice seedlings were treated with 10 μM IAA in darkness for 4 h on a shaker at 40 rpm. Samples were frozen in liquid N2, RNA was then isolated and used for RT-PCR analysis.

To examine the expression of the OsCLE48p-GUS reporter in response to auxin, seedlings of OsCLE48p-GUS transgenic Arabidopsis plants were treated with 10 μM IAA in darkness overnight on a shaker at 40 rpm. GUS activity was examined by histochemical staining.

GUS Staining

Seedlings and different organs collected from adult OsCLE48p-GUS transgenic Arabidopsis plants were stained with X-gluc (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-glucuronide, Rose Scientific Ltd) to monitor GUS activity by following the procedure described by Ulmasov et al. (1997).

Phylogenetic Analysis

Closely related Arabidopsis CLEs to OsCLE48 were identified by BLAST searching Arabidopsis proteome database1 using the entire amino acid sequence of OsCLE48. Full-length amino acid sequences of OsCLE48 and closely related Arabidopsis CLEs were subjected to phylogenetic analysis on Phylogeny2 using “One Click” mode with default settings.

Results

OsCLE48 is an Auxin Responsive Gene Encoding an A-type CLE

The expression of some peptide hormone genes such as PLS and RGF/CLEL/GLV have been shown to be regulated by auxin (Casson et al., 2002; Chilley et al., 2006; Meng et al., 2012b; Whitford et al., 2012), and auxin has been shown to be involved in CLE-induced vascular proliferation (Whitford et al., 2008), however, no CLE genes have been identified as auxin response gene. In an attempt to identify and characterize unknown function auxin response genes in rice, we found that the expression of OsCLE48 (LOC_Os05g48730) was dramatically induced by exogenously application of IAA (Figure 1A), a naturally occurred auxin in plants, indicating that OsCLE48 is an auxin response gene.

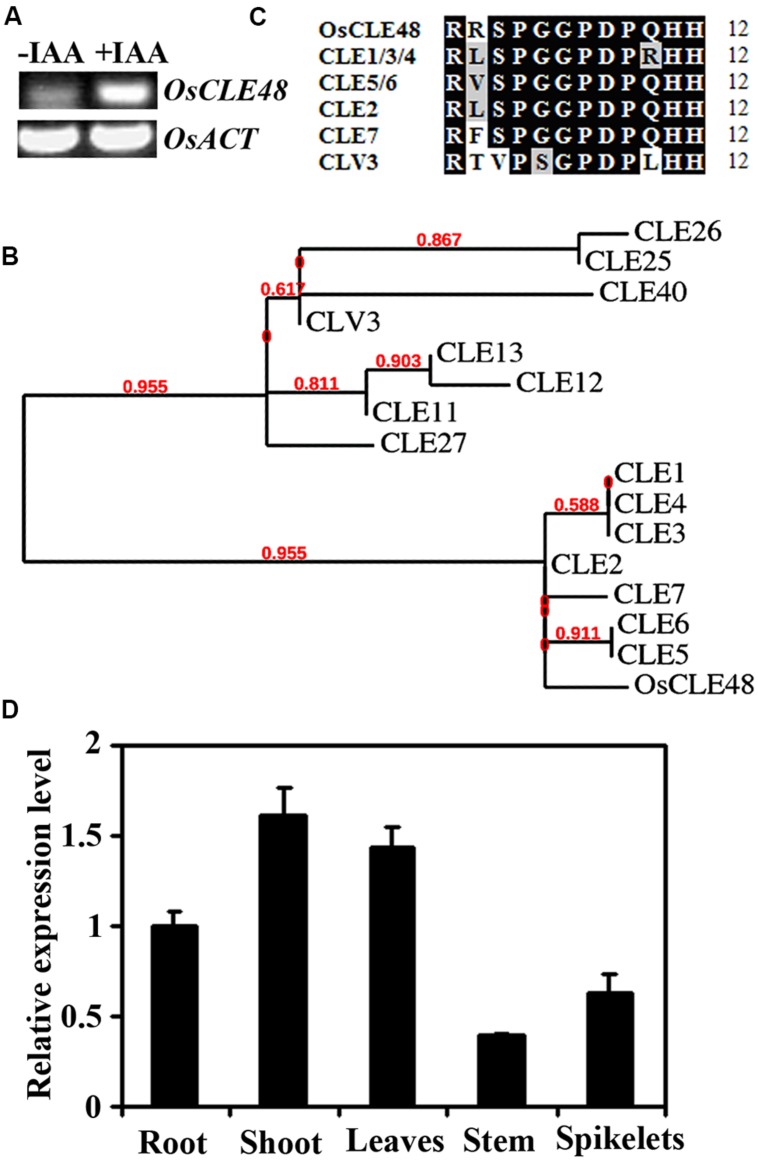

FIGURE 1.

OsCLE48 is an auxin response gene encoding an A-type CLE peptide. (A) Expression of OsCLE48 in response to auxin. Ten-days-old rice seedlings were treated with 10 μM IAA for 4 h, RNA was isolated and RT-PCR was used to examine the expression of OsCLE48. Expression of OsACT2 was used as a control. (B) Phylogenetic analysis of OsCLE48 and some of the A-type Arabidopsis CLEs. The entire amino acid sequences were used for analysis, and the phylogenetic tree was generated on Phylogeny (www.phylogeny.fr) by using the “One Click” mode with default settings. Branch support values are indicated above the branches. The accession codes for the Arabidopsis CLE genes are: CLV3, At2g27250; CLE1, At1g73165; CLE2, At4g18510; CLE3, At1g06225; CLE4, At2g31081; CLE5, At2g31083; CLE6, At2g31085; CLE7, At2g31082; CLE11, At1g49005; CLE12, At1g68795; CLE13, At1g73965; CLE25, At3g28455; CLE26, At1g69970; CLE27, At3g25905; CLE40, At5g12990. (C) Sequence alignment of OsCLE48 peptide and closed related A-type Arabidopsis CLE peptides. Identical amino acids are shaded in black, and similar amino acids in gray. (D) Expression of OsCLE48 in various tissues and organs of rice. RNA was isolated from roots and shoots of 7-days-old seedlings, and leaves, stem and spikelet of mature plants. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to examine the expression of OsCLE48. Rice UBQ5 was used as reference gene, and expression of OsCLE48 in root was set as 1. Data represent mean ± SD of three replications.

OsCLE48 belongs to the CLE gene family in rice. There are at least 47 genes in rice genome encoding CLE proteins. All the CLE proteins have a characteristic amino-terminal signal peptide, and in most of the case, one CLE motif at the carboxyl-terminal (Sawa et al., 2008). By using the entire amino acid sequence of OsCLE48 to BLAST search the Arabidopsis protein database1, we found that OsCLE48 is most closely related to a subgroup of Arabidopsis A-type CLE proteins, CLE1–CLE7. Phylogenetic analysis using the entire amino acid sequences of OsCLE48 and some A-type Arabidopsis CLEs showed that OsCLE48 and CLE1–CLE7 formed one subgroup, whereas CLV3 (CLAVATA3) and a few other A-type Arabidopsis CLEs formed another subgroup (Figure 1B).

Amino acid alignments showed that there is a only one or two aminio acids difference between the 12-amino acid OsCLE48 and CLE1-CLE7 peptides, but four between OsCLE48 and CLV3 peptide (Figure 1C).

Quantitative RT-PCR results showed that OsCLE is expressed in all tissues and organs examined. In rice seedlings, OsCLE48 had relative stronger expression in shoots than in roots. In adult plants, relative higher expression level of OsCLE48 was observed in leaves, whereas lowest expression was observed in stems (Figure 1D).

Expression and Auxin Response of OsCLE48 Promoter in Arabidopsis

None of the Arabidopsis CLE genes has been shown to be an auxin response gene. Having shown that OsCLE48 is an auxin response gene (Figure 1A), it encodes a CLE peptide hormone similar to A-type Arabidopsis CLEs (Figures 1B,C), we wanted to examine if the promoter of OsCLE48 confers auxin response in Arabidopsis. A 1509bp DNA fragment immediately before the start codon of OsCLE48 gene was used to drive the expression of GUS reporter gene in Arabidopsis. Three- and 10-days-old transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings were treated with exogenously IAA, and GUS activity was examined using X-Gluc as substrates. As shown in Figure 2, enhanced GUS staining was observed in seedlings treated with IAA, indicating that the promoter of OsCLE48 is able to response to auxin in Arabidopsis.

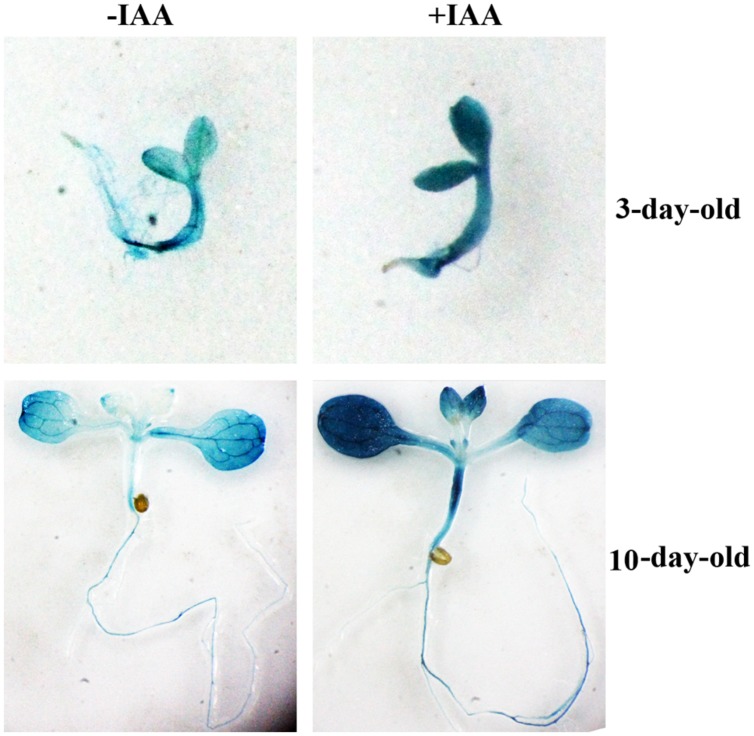

FIGURE 2.

Auxin response of OsCLE48p:GUS reporter gene in Arabidopsis transgenic plants. Arabidopsis transgenic seedlings expressing OsCLE48p:GUS were treated with 10μM IAA overnight. X-Gluc (5-bromo-4-chloro-3indolyl-β-D-glucuronide) was used for histochemical staining to monitor GUS activity.

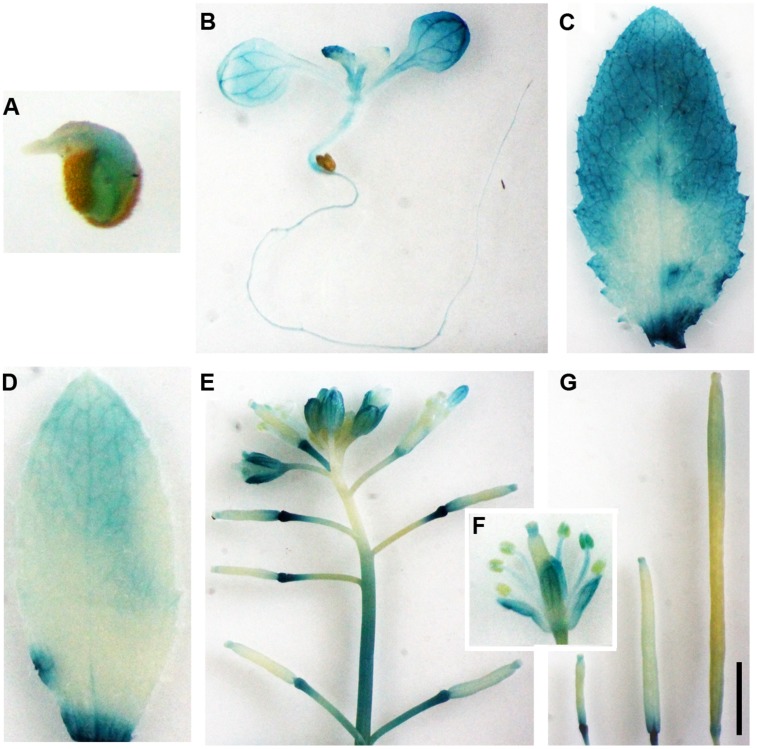

Tissue and/or organ specific expression has been observed for most of the Arabidopsis A-type CLE gene promoters (Jun et al., 2010). To examine if OsCLE48 promoter is tissue and/or organ specific expressed in Arabidopsis, we examine the expression pattern of the OsCLE48 promoter in Arabidopsis. The results showed that GUS activity was detected in germinated seeds, seedlings, and all tissues and organs examined including rosette leaf, cauline leaf, inflorescence, flower, and siliques (Figure 3). Expression of the GUS reporter gene in siliques at different growth stages suggest that the expression of OsCLE48p-GUS is developmental regulated (Figure 3G).

FIGURE 3.

Expression of OsCLE48p:GUS reporter gene in Arabidopsis transgenic plants. Expression of OsCLE48p:GUS in germinated seed (A), seedling (B), rosette leaf (C), cauline leaf (D), inflorescence (E), flower (F), and siliques at different developmental stages (G) in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. X-Gluc was used for histochemical staining to monitor GUS activity. Bar in (G): 3 mm.

OsCLE48 Inhibited Shoot, but not Root Apical Meristem Development in Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants

To examine the possible roles of OsCLE48 in shoot and/or root apical meristem development, we decided to generate Arabidopsis transgenic plants expressing OsCLE48, and to examine the phenotypes of the transgenic plants.

OsCLE48 construct under the control of the 35S promoter was transformed into Arabidopsis Col-0 wild type plants. Multiple lines of transgenic plants with arrested shoot apical meristem were observed. Compared with wild type plant (Figure 4A), the shoot apical meristem of the transgenic plants was arrested at different plant growth stages (Figures 4B–F). On the other hand, root growth in the transgenic plants are largely unaffected (Figure 4G). These results suggest that OsCLE48 regulates shoot, but not root apical meristem development when expressed in Arabidopsis.

FIGURE 4.

Phenotypes of transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing OsCLE48. (A) Wild type plant, (B–F) transgenic plants with shoot apical meristem arrested at different growth stages. Pictures were taken from 3-weeks-old soil-grown plants. Inserts in (A–F), close views of the shoot apical meristems. (G) Seedlings of wild type and transgenic plants (three different lines, two seedlings per line) expressing OsCLE48. Pictures were taken from 7-days-old seedlings grown on vertically plates.

Expression of OsCLE48 Under the Control of the CLV3 cis-Regulatory Elements Rescued the clv3-2 Mutant Phenotypes

CLV3 is the only Arabidopsis CLE identified by mutagenesis, and lost-of-function mutants of CLV3 gene have enlarged shoot and floral apical meristems with extra floral organs (Clark et al., 1995; Fletcher et al., 1999), whereas all other null mutants identified for other A-type CLE genes are largely morphological indistinguishable from wild type plants (Jun et al., 2010). Having shown that expression of OsCLE48 in Arabidopsis resulted in arrested shoot apical meristem (Figure 4), a phenotype observed in transgeninc plants overexpressing some of the A-type CLE genes (Jun et al., 2010; Katsir et al., 2011), we tested whether OsCLE48 will rescue the clv3 mutant phenotypes when expressed under the control of the CLV3 cis-regulatory elements in the clv3-2 mutant.

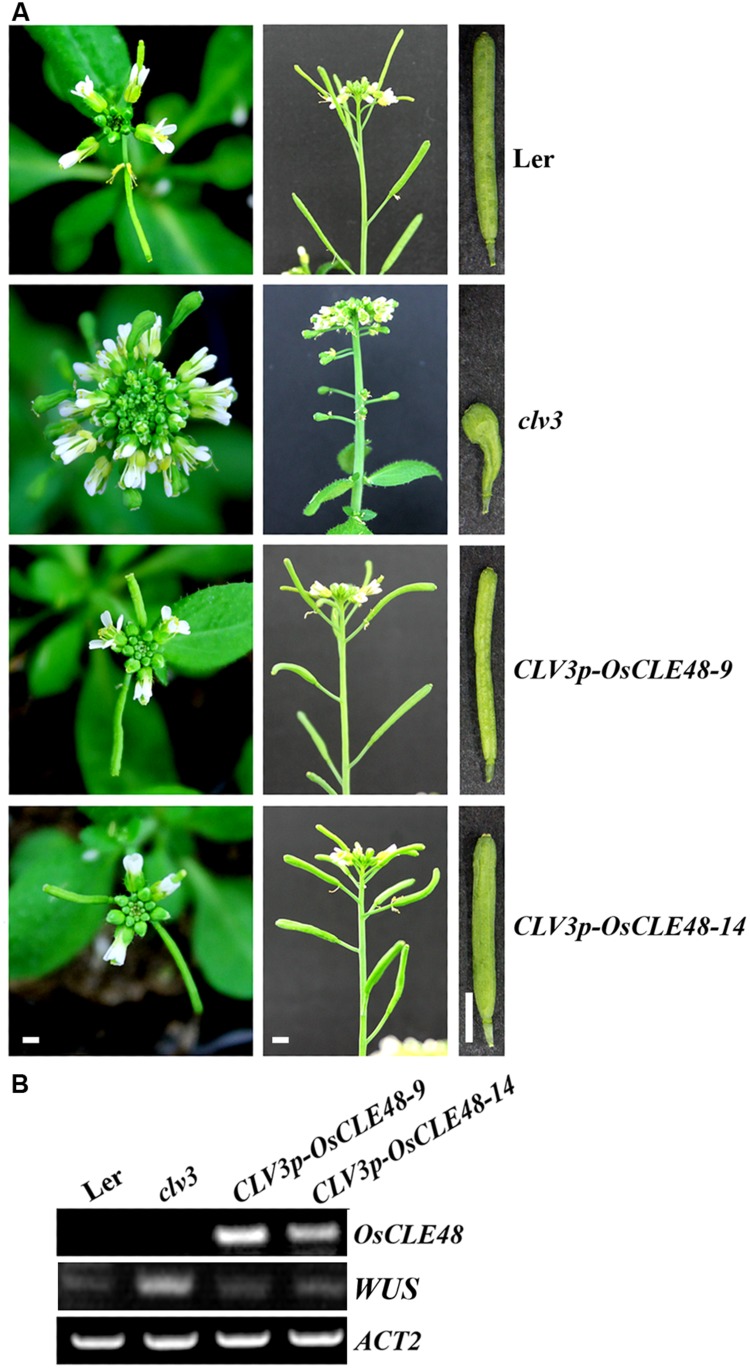

The CLV3p-OsCLE48 construct was generated by replacing the 35S promoter and the nos terminator in the 35S-OsCLE48 construct with the 5′ upstream and 3′ downstream regulatory sequence of CLV3 (Brand et al., 2002), respectively. The construct was transformed into clv3-2 mutants, and phenotypes in the transgenic plants were examined. As described previously (Clark et al., 1995; Fletcher et al., 1999), clv3-2 mutant plants produce enlarged floral apical meristem, short siliques with increased number of carpels (Figure 5A), whereas these phenotypes were almost completely rescued by the entopic expression of OsCLE48 (Figure 5A). The expression of WUSCHEL (WUS) in the transgenic plants was also restored to wild type level in the clv3-2 mutant plants expressing OsCLE48 (Figure 5B). These results indicate that OsCLE48 is functional equivalent to CLV3 in regulating shoot apical meristem development in Arabidopsis.

FIGURE 5.

Rescue of clv3-2 mutant phenotype by OsCLE48. (A) Inflorescence and silique phenotypes of wild type, clv3-2, and CLV3p-OsCLE48/clv3-2 plants. Pictures were taken from 5-weeks-old soil-grown plants. (B) Expression of OsCLE48 and WUS in transgenic plants. RNA was isolated from 10-days-old seedlings of wild type, clv3-2, and CLV3p-OsCLE48/clv3-2 plants, RT-PCR was used to examine the expression of OsCLE48. Expression of ACT2 was used as a control. Bar: 2 mm, all corresponding photos were taken at same magnification.

Shoot Apical Meristem Development is Largely Unaffected in Transgeinc Rice Plants Overexpressing OsCLE48

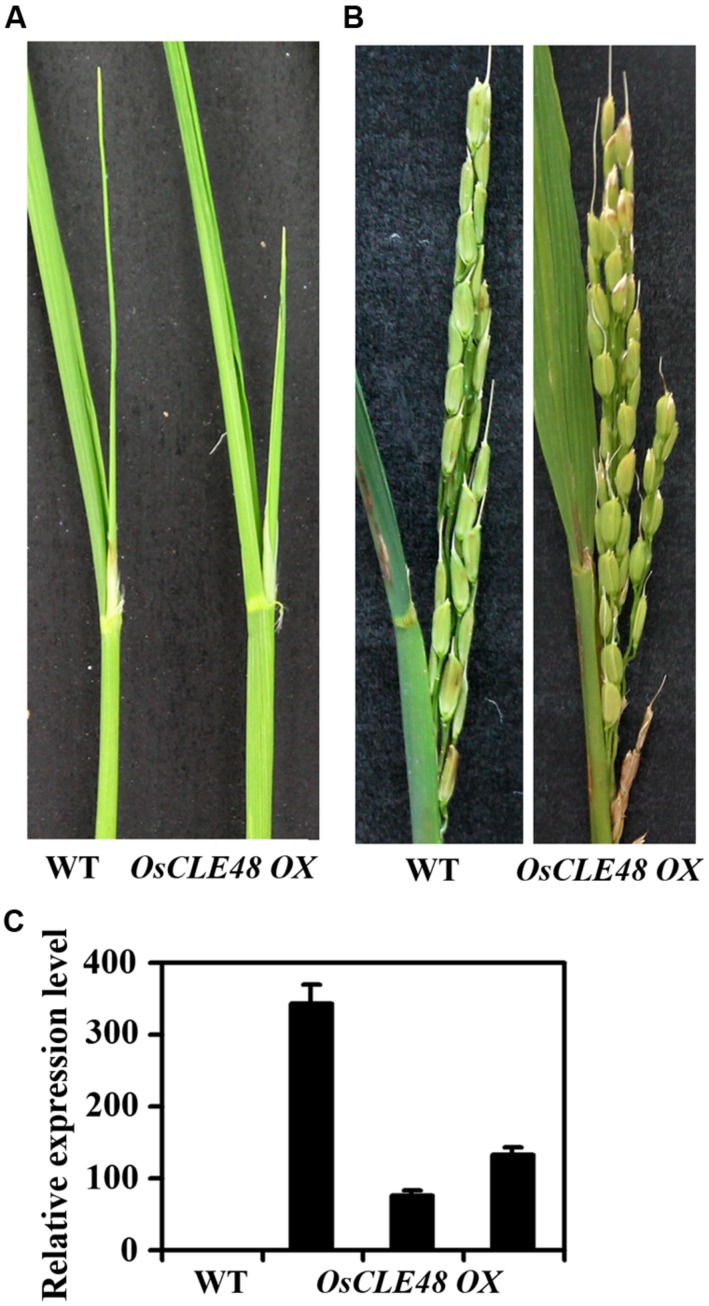

To examine if OsCLE48 may also play a role in the regulating shoot apical meristem development in rice, we generated transgenic rice plants expressing OsCLE48 under the control of the 35S promoter. As shown in Figure 6A, shoot development in transgenic rice plants was largely unaffected when compared with wild type plants, and panicles in the transgenic plants was also indistinguishable from that in wild type plants (Figure 6B). The overexpression of OsCLE48 in the transgenic plants was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 6C), rolled out the possibility that the morphological similarity observed between transgenic and wild type plants was due to low expression levels of the OsCLE48 gene.

FIGURE 6.

Phenotypes of rice transgenic plants overexpressing OsCLE48. (A) Shoots and (B) Panicles of wild and transgenic rice plants overexpressing OsCLE48. (C) Expression of OsCLE48 in wild type and three different lines of transgenic rice plants. RNA was isolated from rice leaves. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to examine the expression of OsCLE48. UBQ5 was used as control reference gene. Expression of OsCLE48 in wild type was set as 1. Data represent mean ± SD of three replications.

Discussion

Plant hormone auxin and peptide hormones have overlapping functions in regulating plant growth and development. Experimental evidence have showed that the expression of some peptide genes such as PLS and RGF/CLEL/GLV are regulated by auxin (Casson et al., 2002; Chilley et al., 2006; Meng et al., 2012b; Whitford et al., 2012), and auxin is involved in CLE-induced vascular proliferation (Whitford et al., 2008). There are 32 genes in Arabidopsis genome, and at least 47 genes in rice genome, encoding CLEs (Kinoshita et al., 2007; Sawa et al., 2008; Jun et al., 2010), however, none of them have been shown to be regulated by auxin. We provide evidence in this study that OsCLE48 is an auxin response gene, and it regulates shoot apical meristem development when expressed in Arabidopsis.

RT-PCR results showed that the expression of OsCLE48 in rice seedlings was induced by auxin treatment (Figure 1A). The expression of the integrated OsCLE48p-GUS reporter gene in transgenic Arabidopsis was also induced by auxin treatment (Figure 2). Sequence scanning showed that there is a TGTCTC auxin response element in the 1509 bp promoter region of OsCLE483, it may responsible for the auxin response observed for OsCLE48 gene. These results indicate the OsCLE48 is an auxin response gene, and its promoter confers auxin responsiveness in Arabidopsis. Phylogenic analysis showed that OsCLE48 is closely related to a subgroup of A-type Arabidopsis CLEs (Figure 1B), and OsCLE48 contains a conserved CLE motif (Figure 1C). Taken together, these evidence supports that OsCLE48 is an auxin response CLE gene.

It has been shown that peptide hormones are involved in auxin transport (Chilley et al., 2006; Whitford et al., 2012), and auxin is involved in CLE-induced vascular proliferation (Whitford et al., 2008). We show here that OsCLE48 is an auxin response gene, thus it may worthwhile to examine if OsCLE48 is involved in regulating auxin transport and/or signaling, in a feed back manner.

Some of the Arabidopsis CLE peptide hormones have been shown to regulate shoot and/or root apical meristem maintenance (Kinoshita et al., 2007; Jun et al., 2010; Katsir et al., 2011). Several rice CLEs have also been shown to regulate shoot and root apical meristem development (Chu et al., 2006; Suzaki et al., 2006, 2009). The OsCLE48-GUS reporter is expressed in all tissues and organs examined in transgenic Arabidopsis (Figure 3), a pattern different from that of all the Arabidopsis CLE gene promoters tested (Jun et al., 2010). However, expression of OsCLE48 under the control of the 35S promoter in Arabidopsis arrested shoot apical meristem development (Figure 4), a phenotype similar to that observed in Arabidopsis transgenic plants overexpressing some of the CLE genes (Jun et al., 2010). Expression of OsCLE48 in the clv3-2 mutant under the control of the CLV3 regulatory elements almost completely rescued the clv3-2 mutant phenotypes (Figure 5A). WUS is a key regulatory factor controlling shoot apical meristem stem cell populations. Expression of WUS is regulated by CLV3 signaling, in turn, WUS regulates CLV3 expression in a feedback manner (Brand et al., 2000, 2002; Schoof et al., 2000). Our RT-PCR results showed that the expression of WUS in clv3-2 was restored to wild type level by expressing OsCLE48 under the control of CLV3 cis-regulatory elements (Figure 5B). These results suggest that OsCLE48 encodes a functional CLE peptide hormone. It should note that CLE5/6 is closely related to OsCLE48 (Figure 1), however, exogenously application of CLE6/7 peptides does not have any effects in Arabidopsis (Kinoshita et al., 2007), possibly because exogenously application of CLE peptides and overexpression of a CLE gene in plant may not always have the same effects.

Several rice CLEs including FLORAL ORGA NUMBER 2 (FON2), FON4, and FON2 SPARE1 (FOS1) have been shown to involve in the regulation of shoot and/or root apical meristem development in rice (Chu et al., 2006; Suzaki et al., 2006, 2009). Both fon2 and fon4 mutants have enlarged floral meristem and increased numbers of floral organs (Chu et al., 2006; Suzaki et al., 2006), a phenotype similar to that of clv3 mutants (Clark et al., 1995; Fletcher et al., 1999). On the other hand, transgenic rice plants overexpressing FON2 have reduced number of flowers and floral organs (Suzaki et al., 2006), overexpressing of FOS1 in rice resulted in arrested shoot meristem (Suzaki et al., 2009), exogenous application of FON4 peptides also resulted in termination of shoot apical meristem (Chu et al., 2006), whereas overexpression of FON2 in Arabidopsis resulted in termination of shoot apical meristem (Suzaki et al., 2006). Our results showed that transgenic rice plants overexpressing OsCLE48 were morphological indistinguishable from wild type plants (Figure 6). We could not role out the possibility that OsCLE48 may regulate shoot apical meristem development in rice without examining lost-of-function mutants. However, there is no loss-of-function mutant available for OsCLE48 gene. On the other hand, considering that there are at least 47 genes in rice genome encoding CLEs, and there is only one amino acid different between the OsCLE48 peptide and CLE peptides produced by several other CLE genes (Sawa et al., 2008), it is likely that OsCLE48 may have redundant functions with some other CLE genes. Recently, antagonistic peptide technology has been shown to be an efficient way to analyze the functions of some CLEs in Arabidopsis (Song et al., 2013), consequently to create antagonistic peptides of OsCLE48 and examine their functions in rice may uncover the roles played by OsCLE48 in rice.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The clv3-2 mutant seeds were provided by Dr. Chun-Ming Liu (Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences). This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31470297), and the startup funds from Northeast Normal University4.

Footnotes

References

- Brand U., Fletcher J. C., Hobe M., Meyerowitz E. M., Simon R. (2000). Dependence of stem cell fate in Arabidopsis on a feedback loop regulated by CLV3 activity. Science 289 617–619 10.1126/science.289.5479.617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand U., Grünewald M., Hobe M., Simon R. (2002). Regulation of CLV3 expression by two homeobox genes in Arabidopsis. Plant physiol. 129 565–575 10.1104/pp.001867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butenko M. A., Patterson S. E., Grini P. E., Stenvik G. E., Amundsen S. S., Mandal A., et al. (2003). Inflorescence deficient in abscission controls floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis and identifies a novel family of putative ligands in plants. Plant Cell 15 2296–2307 10.1105/tpc.0143655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casson S. A., Chilley P. M., Topping J. F., Evans I. M., Souter M. A., Lindsey K. (2002). The POLARIS gene of Arabidopsis encodes a predicted peptide required for correct root growth and leaf vascular patterning. Plant Cell 14 1705–1721 10.1105/tpc.002618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman E. J., Estelle M. (2009). Mechanism of auxin-regulated gene expression in plants. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43 265–285 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charon C., Johansson C., Kondorosi E., Kondorosi A., Crespi M. (1997). Enod40 induces dedifferentiation and division of root cortical cells in legumes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 8901–8906 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilley P. M., Casson S. A., Tarkowski P., Hawkins N., Wang K. L., Hussey P. J., et al. (2006). The POLARIS peptide of Arabidopsis regulates auxin transport and root growth via effects on ethylene signaling. Plant Cell 18 3058–3072 10.1105/tpc.106.040790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S. K., Larue C. T., Chevalier D., Wang H., Jinn T. L., Zhang S., et al. (2008). Regulation of floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 15629–15634 10.1073/pnas.0805539105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H., Qian Q., Liang W., Yin C., Tan H., Yao X., et al. (2006). The floral organ number4 gene encoding a putative ortholog of Arabidopsis CLAVATA3 regulates apical meristem size in rice. Plant Physiol. 142 1039–1052 10.1104/pp.106.086736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S. E., Running M. P., Meyerowitz E. M. (1995). CLAVATA3 is a specific regulator of shoot and floral meristem development affecting the same processes as CLAVATA1. Development 121 2057–2067. [Google Scholar]

- Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16 735–743 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constabel C. P., Yip L., Ryan C. A. (1998). Prosystemin from potato, black nightshade, and bell pepper: primary structure and biological activity of predicted systemin polypeptides. Plant Mol. Biol. 36 55–62 10.1023/A:1005986004615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coudert Y., Dievart A., Droc G., Gantet P. (2013). ASL/LBD phylogeny suggests that genetic mechanisms of root initiation downstream of auxin are distinct in lycophytes and euphyllophytes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 569–572 10.1093/molbev/mss250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P. J. (1995). Plant Hormones: Physiology, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 10.1007/978-94-011-0473-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmasiri N., Dharmasiri S., Estelle M. (2005). The F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature 435 441–445 10.1038/nature03543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund T., Jessell T. M. (1999). Progression from extrinsic to intrinsic signaling in cell fate specification: a view from the nervous system. Cell 96 211–224 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80561-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A., Drozdzecki A., Hoogewijs K., Nguyen A., Beeckman T., Madder A., et al. (2013). Transcriptional and functional classification of the GOLVEN/ROOT GROWTH FACTOR/CLE-like signaling peptides reveals their role in lateral root and hair formation. Plant Physiol. 161 954–970 10.1104/pp.112.206029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher J. C., Brand U., Running M. P., Simon R., Meyerowitz E. M. (1999). Signaling of cell fate decisions by CLAVATA3 in Arabidopsis shoot apical meristems. Science 283 1911–1914 10.1126/science.283.5409.1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraldes A., Pang J., Thiessen N., Cezard T., Moore R., Zhao Y., et al. (2011). SNP discovery in black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa) by population transcriptome resequencing. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 11(Suppl. 1) 81–92 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02960.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain H., Chevalier E., Matton D. (2006). Plant bioactive peptides: an expanding class of signalling molecules. Can. J. Bot. 84 1–19 10.1139/b05-162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guilfoyle T. J., Hagen G. (2007). Auxin response factors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10 453–460 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen G., Guilfoyle T. J. (2002). Auxin-responsive gene expression: genes, promoters, and regulatory factors. Plant Mol. Biol. 49 373–485 10.1023/A:1015207114117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K., Kajita R., Torii K. U., Bergmann D. C., Kakimoto T. (2007). The secretory peptide gene EPF1 enforces the stomatal one-cell-spacing rule. Genes Dev. 21 1720–1725 10.1101/gad.1550707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto Y., Kondo T., Kageyama Y. (2008). Lilliputians get into the limelight: novel class of small peptide genes in morphogenesis. Dev. Growth Differ. 50(Suppl. 1) S269–S276 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2008.00994.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K.-I. (2012). The interaction and integration of auxin signaling components. Plant Cell Physiol. 53 965–975 10.1093/pcp/pcs035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiei Y., Ohta S., Komari T., Kumashiro T. (1994). Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J. 6 271–282 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1994.6020271.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt L., Gray J. E. (2009). The signaling peptide EPF2 controls asymmetric cell divisions during stomatal development. Curr. Biol. 19 864–869 10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M., Nijhawan A., Tyagi A. K., Khurana J. P. (2006). Validation of housekeeping genes as internal control for studying gene expression in rice by quantitative real-time PCR. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 345 646–651 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun J., Fiume E., Roeder A. H., Meng L., Sharma V. K., Osmont K. S., et al. (2010). Comprehensive analysis of CLE polypeptide signaling gene expression and overexpression activity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 154 1721–1736 10.1104/pp.110.163683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsir L., Davies K. A., Bergmann D. C., Laux T. (2011). Peptide signaling in plant development. Curr. Biol. 21 356–364 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepinski S., Leyser O. (2005). The Arabidopsis F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature 435 446–451 10.1038/nature03542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer M., Neve J., Kepinski S. (2010). Defining auxin response contexts in plant development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13 12–20 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita A., Nakamura Y., Sasaki E., Kyozuka J., Fukuda H., Sawa S. (2007). Gain-of-function phenotypes of chemically synthetic CLAVATA3/ESR-related (CLE) peptides in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. Plant Cell Physiol. 48 1821–1825 10.1093/pcp/pcm154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leasure C. D., He Z.-H. (2012). CLE and RGF family peptide hormone signaling in plant development. Mol. Plant 5 1173–1175 10.1093/mp/sss082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. W., Kim N. Y., Lee D. J., Kim J. (2009). LBD18/ASL20 regulates lateral root formation in combination with LBD16/ASL18 downstream of ARF7 and ARF19 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 151 1377–1389 10.1104/pp.109.143685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi Y. (2011). Post-translational modifications in secreted peptide hormones in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 52 5–13 10.1093/pcp/pcq169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki Y., Ogawa-Ohnishi M., Mori A., Matsubayashi Y. (2010). Secreted peptide signals required for maintenance of root stem cell niche in Arabidopsis. Science 329 1065–1067 10.1126/science.1191132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L., Buchanan B. B., Feldman L. J., Luan S. (2012a). CLE-like (CLEL) peptides control the pattern of root growth and lateral root development in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 1760–1765 10.1073/pnas.1119864109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L., Buchanan B. B., Feldman L. J., Luan S. (2012b). A putative nuclear CLE-like (CLEL) peptide precursor regulates root growth in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 5 955–957 10.1093/mp/sss060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita N. N., Moore S., Horiguchi G., Kubo M., Demura T., Fukuda H., et al. (2004). Overexpression of a novel small peptide ROTUNDIFOLIA4 decreases cell proliferation and alters leaf shape in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 38 699–713 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02078.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce G., Moura D. S., Stratmann J., Ryan C. A. (2001). Production of multiple plant hormones from a single polyprotein precursor. Nature 411 817–820 10.1038/35081107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce G., Strydom D., Johnson S., Ryan C. A. (1991). A polypeptide from tomato leaves induces wound-inducible proteinase inhibitor proteins. Science 253 895–898 10.1126/science.253.5022.895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa S., Kinoshita A., Betsuyaku S., Fukuda H. (2008). A large family of genes that share homology with CLE domain in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Signal. Behav. 3 337–339 10.4161/psb.3.5.5344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoof H., Lenhard M., Haecker A., Mayer K. F., Jürgens G., Laux T. (2000). The stem cell population of Arabidopsis shoot meristems in maintained by a regulatory loop between the CLAVATA and WUSCHEL genes. Cell 100 635–644 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80700-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X. F., Guo P., Ren S. C., Xu T. T., Liu C. M. (2013). Antagonistic peptide technology for functional dissection of CLV3/ESR genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 161 1076–1085 10.1104/pp.112.211029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenvik G. E., Tandstad N. M., Guo Y., Shi C. L., Kristiansen W., Holmgren A., et al. (2008). The EPIP peptide of INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION is sufficient to induce abscission in Arabidopsis through the receptor-like kinases HAESA and HAESA-LIKE2. Plant Cell 20 1805–1817 10.1105/tpc.108.059139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugano S. S., Shimada T., Imai Y., Okawa K., Tamai A., Mori M., et al. (2010). Stomagen positively regulates stomatal density in Arabidopsis. Nature 463 241–244 10.1038/nature08682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzaki T., Ohneda M., Toriba T., Yoshida A., Hirano H. Y. (2009). FON2 SPARE1 redundantly regulates floral meristem maintenance with FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER2 in rice. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000693 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzaki T., Toriba T., Fujimoto M., Tsutsumi N., Kitano H., Hirano H. Y. (2006). Conservation and diversification of meristem maintenance mechanism in Oryza sativa: Function of the FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER2 gene. Plant Cell Physiol. 47 1591–1602 10.1093/pcp/pcl025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X., Calderon-Villalobos L. I., Sharon M., Zheng C., Robinson C. V., Estelle M., et al. (2007). Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitun ligase. Nature 446 640–645 10.1038/nature05731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T., Murfett J., Hagen G., Guilfoyle T. J. (1997). Aux/IAA proteins repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. Plant Cell 9 1963–1971 10.1105/tpc.9.11.1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Li E., Porth I., Chen J. G., Mansfield S. D., Douglas C. J. (2014). Regulation of secondary cell wall biosynthesis by poplar R2R3 MYB transcription factor PtrMYB152 in Arabidopsis. Sci. Rep. 4:5054 10.1038/srep05054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J., Lease K. A., Walker J. C. (2004). DVL, a novel class of small polypeptides: overexpression alters Arabidopsis development. Plant J. 37 668–677 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2003.01994.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitford R., Fernandez A., De Groodt R., Orteqa E., Hilson P. (2008). Plant CLE peptides from two distinct functional classes synergistically induce division of vascular cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 18625–19630 10.1073/pnas.0809395105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitford R., Fernandez A., Tejos R., Pérez A. C., Kleine-Vehn J., Vanneste S., et al. (2012). GOLVEN secretory peptides regulate auxin carrier turnover during plant gravitropic responses. Dev. Cell 22 678–685 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]