Abstract

Objective

We examined the performance of the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) and the short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA) in caregivers of children.

Method

Caregivers of children ≤ 12 years old seeking care for their child in a pediatric emergency department were tested using the NVS and the S-TOFHLA to measure health literacy. The results were compared with ED use outcomes.

Result

The S-TOFHLA was found to have a ceiling effect as compared to the NVS; few caregivers scored in low literacy categories (p < 0.0001). This finding was demonstrated in both lower (p=0.01) and higher (p < 0.001) educational attainment groups. The NVS was predictive of ED use outcomes (p=0.02 and p<0.01) whereas the S-TOFHLA was not (p=0.21, p=0.11).

Conclusions

The measures do not seem to function similarly nor predict health outcomes equally. The NVS demonstrates sensitivity in identifying limited health literacy in younger adult populations.

Keywords: Health literacy, Newest Vital Sign, Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults, infant, child, preschool, child

Introduction

Over 90 million American adults have limited health literacy, affecting their ability to make appropriate health decisions.1 Health literacy has been defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.” 1 Limited health literacy is associated with worse disease specific outcomes, less primary care and preventative visits, increased ED visits and hospitalizations resulting in increased mortality.2 Given the association with important health outcomes, the ability to evaluate health literacy is crucial to provide our patients with the highest quality of care.

Much of the evidence of the effects of limited health literacy has resulted from study in adults, and likewise, measures of health literacy have been developed mainly for populations of adult patients. Pediatrics presents a unique situation where a surrogate decision maker, a parent or caregiver, is making health decisions for the patient. Researchers have acknowledged differences in measurement of health literacy in this population with a ceiling effect being found.3 Prior use of versions of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) in parents has shown a prominent ceiling effect,3–5 making analysis difficult. This ceiling effect may be partially attributable to differences in the population of parents who are, as a whole, younger than the general adult population. On a national level, parents have better health literacy (26% low health literacy) as compared to the adult population of non-parents (36%).6 There is also uncertainty that the original cut-off functions well when investigating outcomes in a younger population.7 Others have speculated that health literacy has a dose-dependent effect on health outcomes, and the categorization of limited and adequate health literacy may depend on the population studied.8 This acknowledged difference has resulted in development of pediatric specific health literacy measures such as the Parent Health Literacy Assessment Test.3 These measures are of limited use in some settings due to a length of administration time over 20 minutes.

One brief, validated measure of health literacy, the Newest Vital Sign (NVS), tests both document and quantitative literacy, and was validated using the S-TOFHLA.9 In a previous study of health literacy by the authors of this study, the NVS showed measure predictive ability for health outcomes in the population of caregivers of children.7 The NVS was able to determine differences in care-seeking behavior for ED utilization based on health literacy. Further, this study described the need for a different threshold in caregivers of children, at least for that population.

In this study, we sought to determine the differences between the NVS and the S-TOFHLA. We hypothesized that the NVS would function without a ceiling effect in parents of young children as compared to the S-TOFHLA. In addition, we hypothesized that the NVS will be more predictive of health outcomes than the S-TOFHLA, specifically non-urgent emergency department (ED) use and ED utilization, important for the reliability of this measure to detect limited health literacy in samples of parents.

Method

Participants

This was a planned analysis of a study conducted to investigate the association between limited health literacy and emergency department utilization. 7 Caregivers (parent or legal guardian) ≥ 18 years of age of children ≤ 12 years old presenting to the ED at a tertiary Midwest children’s hospital serving an urban and suburban population were recruited for participation. Subjects were excluded if the caregiver had already completed the study, did not speak English or Spanish, if the child was in acute distress (e.g., highest triage acuity level), or presented for child maltreatment or non-accidental trauma. The hospital’s Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Materials and Procedure

Procedure

Caregivers were enrolled during pre-determined four-hour blocks encompassing daytime, evening, and weekend hours between June 1, 2011 and May 31, 2012. In order to obtain a cross-sectional sample of the ED population, a room number was selected from a random list of ED room numbers every 30 minutes and a caregiver in that room was eligible for enrollment. This enrollment method allowed for collection of a variety of health literacy abilities not limited by a convenience sample. Verbal consent was obtained using a script written at a fifth grade reading level during which a written copy was provided for the caregiver. After consent, the research assistant verbally administered the NVS 9 and the S-TOFHLA10 to assess health literacy and provided a self-administered survey of sociodemographic information. The NVS and S-TOFHLA were counterbalanced to reduce bias due to test fatigue.

Newest Vital Sign (NVS)

The NVS is a six-question test orally administered to assess health literacy and numeracy.9 The NVS requires interpretation of a nutrition facts label to answer health related questions including the performance of calculations; tasks which are thought to measure the composite skills of both print and numeric literacy. The NVS has been validated for administration in both English and Spanish and is ideal for the ED environment taking only 2–6 minutes to administer. The NVS is scored as high likelihood of limited literacy (0–1 correct), possibility of limited literacy (2–3 correct), and adequate literacy (4–6 correct) based on the prediction of adequate health literacy by the TOFHLA in the NVS validation study.9 Four items on the NVS contain quantitative (numeracy) skills along with literacy skills, while two questions assess document literacy skills only.

Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA)

The S-TOFHLA contains thirty-six cloze passages involving reading comprehension of patient medical documents to assess document health literacy.10 Four numeracy questions are included, requiring interpretation of medication instructions, test results, and an appointment slip. The initial cloze passages are time limited at 7 minutes. The remainder of the questions takes approximately 5 minutes to complete, for a total of 12 minutes. The S-TOFHLA is scored as inadequate functional health literacy (score 0–53), marginal functional health literacy (54–66), and adequate functional health literacy (67–100).

Non-Urgent Index ED Visit

Resources used during the visit at which the subject was enrolled, the index ED visit, were reviewed to classify visits as urgent or non-urgent using similar to previous studies of non-urgent ED use.11,12 A research assistant, different from the research assistant who enrolled the caregiver, reviewed the ED chart and recorded all resources used. Consistent with prior published standards, visits were considered urgent if the child utilized any diagnostic testing (including blood work, urine studies, electrocardiography, or other fluids such as CSF or joint aspirate, excluding strep or rapid antigen swabs), radiologic studies, administration of IV fluids, or provision of any medication (excluding oral antibiotics and over the counter medications).11–13 All other visits were considered non-urgent.

Prior ED Use

A regional database recording ED use from 29 ED sites in the surrounding city and state was available as part of the medical record. The research assistant reviewed the database printout and the number of ED visits over the prior 365 days extracted. This data was missing for 25% of subjects when the database was offline.

Statistical analyses

Demographic characteristics were compiled using descriptive statistics. NVS and the S-TOFHLA were scored as a raw score as well as 3-category categorization into limited/inadequate (referred to as low), marginal/possibility of limited (referred to as marginal), and adequate health literacy. An ordinal chi-square test was used to compare the proportions of each category for the NVS and S-TOFHLA scores. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to evaluate the shared variance of the scores (r2) on the NVS and S-TOFHLA as well as the numeracy items on each of the tests. The analysis was stratified by educational attainment to assess the performance of the tests in these sub-populations.

To determine the predictive ability of the NVS and brief TOFHLA, an ordinal chi-square was used to compare the proportions of each category for non-urgent ED use as well as proportion of patients with greater than three prior ED visits (highest utilizers).

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Medical College of Wisconsin. SAS OnDemand Enterprise Guide software, Version 4.3 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary NC) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

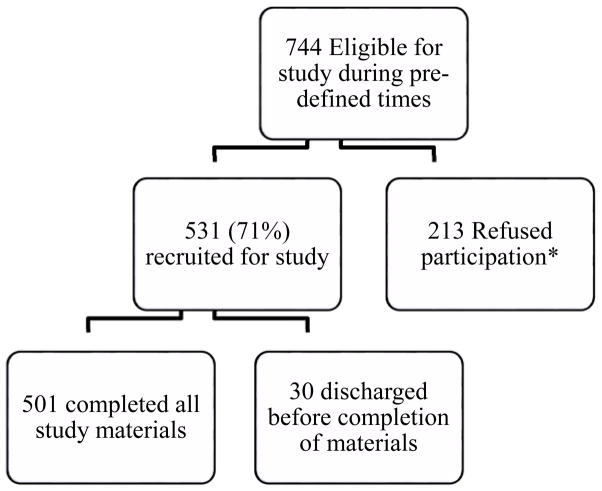

During eligible periods, 744 caregivers/child pairs were eligible, 531 consented (71%), and 501 completed all study materials (Figure 1). Caregivers were a median age of 32.4 (range 18–69) years, almost all were female, and 46% were white, 37% black, and 10% Hispanic. (Table 1) Notably, 62% of caregivers had training or education beyond high school.

Figure 1.

Study Subject Flow Diagram.

*Refused subjects did not differ from study subjects in age (p= 0.09), triage level (p = 0.36), or month of recruitment (0.39).

Table 1.

Caregiver and Child Characteristics

| % | |

|---|---|

| Caregiver (n=501) | |

| Age, y, median (range) | (32.4; 18–69) |

| Female gender | 85.4 |

| Foreign born | 15.2 |

| Ethnicity/race | |

| White | 46.9 |

| Black | 37.1 |

| Hispanic | 9.6 |

| Other | 5.0 |

| Education | |

| Less than HS | 12.2 |

| Graduated HS | 24.8 |

| 1–4 years college | 30.9 |

| ≥ College degree | 31.3 |

| Child | |

| Age, y, median (range) | (4.5; 0.06–12) |

| Insurance | |

| Private | 32.3 |

| Public | 64.1 |

| None | 1.0 |

Comparison of the NVS and S-TOFHLA

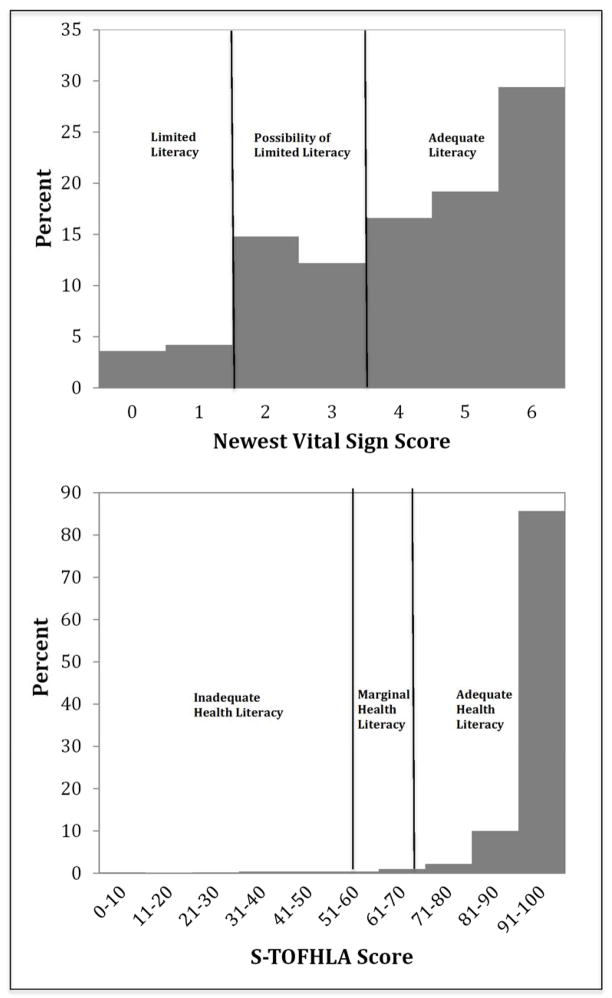

The distribution of scores across the scoring spectrum is wider on the NVS compared to the S-TOFHLA. As seen in Figure 2, the NVS scores are spread across the spectrum with a slight left shift. In contrast, the S-TOFHLA scores are nearly all at the right (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The NVS Categories Caregivers Across Score Categories

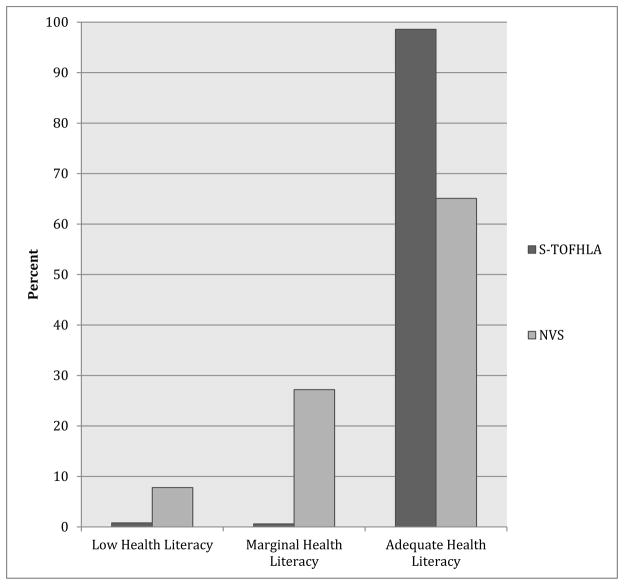

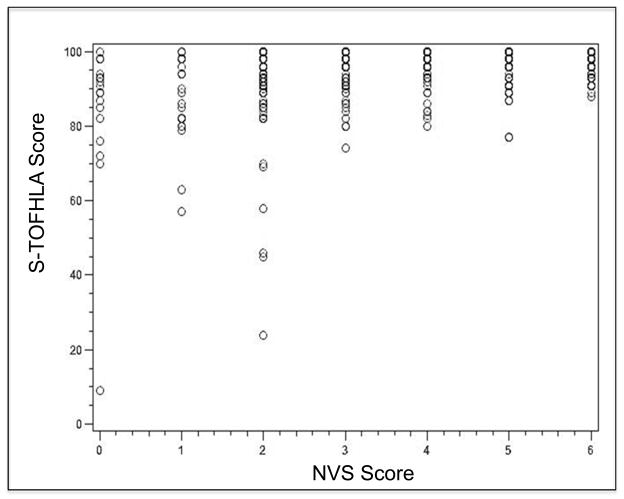

The scores between the S-TOFHLA and the NVS are significantly different when analyzed by proportions of scores in each score category (p<0.001, Figure 3). If a caregiver scored limited or marginal health literacy on S-TOFHLA (n=7), 100% were classified as limited or possibility of limited literacy on the NVS. Of those caregivers scoring adequate on the S-TOFHLA, 7% were categorized as limited health literacy on the NVS and 26% categorized as possibility of limited literacy, demonstrating the ceiling effect of the S-TOFHLA (Table 2). A scatterplot of the S-TOFHLA compared to the NVS (Figure 4) visually depicts the ceiling effect with the S-TOFHLA scores situated near the top of the plot, indicating high scores. When evaluating the scores as a continuous variable rather than categorical, the tests remain significantly different with only 20% of the variance of the scores being shared (Spearman’s correlation p<0.0001 r=0.45).

Figure 3.

Score Categories for S-TOFHLA and NVS

Table 2.

Number of Caregivers in Each Health Literacy Category

| Newest Vital Sign

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Marginal | Adequate | ||

|

|

||||

| S- TOFHLA | Low | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Marginal | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Adequate | 36 | 131 | 326 | |

Figure 4.

Scatterplot of NVS Score in Comparison to S-TOFHLA score

Numeracy Items

In comparing the numeracy items on the S-TOFHLA to the NVS, only 10% of the variance is shared between the two measures (Spearman’s correlation p<0.0001, r=0.32).

Educational Attainment and Score Categorization

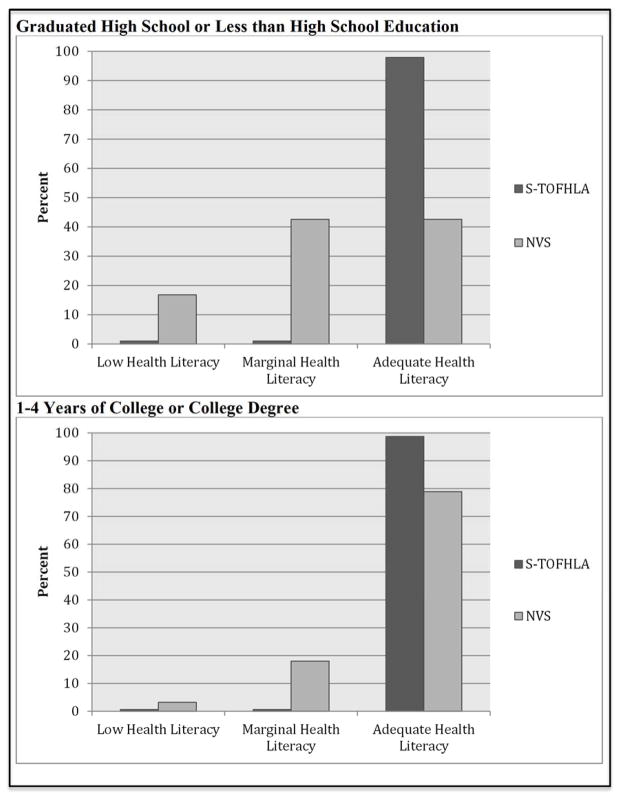

Scores on each of the measures were stratified by educational attainment. The NVS categorizes across all score categories whether the caregiver has lower or higher educational attainment whereas the S-TOFHLA classifies few caregivers in the lowest categories (Figure 5). The proportion of scores in each category are significantly different between the NVS and the S-TOFHLA in both lower (p=0.01) and higher (p < 0.001) educational attainment groups. When comparing continuous scores, the tests are significantly different in both the lower (Spearman’s correlation p < 0.001, r=0.47) and higher (p<0.0001, r=0.32) educational attainment groups.

Figure 5.

Score Categorizations by Educational Attainment

Predictive Ability of NVS and S-TOFHLA

To further evaluate the predictive ability of each measure, an ordinal chi-square test was used to evaluate the non-urgent ED outcome. Lower scores on the NVS are associated with increased odds of a non-urgent index ED visit (p = 0.02). The S-TOFHLA did not predict a non-urgent ED visit (p=0.21). For prior ED visits, lower NVS scores were related to more high utilizers of the ED (p <0.01) but the S-TOFHLA was not (p=0.11).

Discussion

Accurate categorization of health literacy is important to determine the effect of health literacy on health outcomes. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to compare health literacy in caregivers of children (parents and guardians) with both the S-TOFHLA and the NVS. We found that the measures do not function similarly and only 20% of the variance of the scores is equivalent. We found that the S-TOFHLA has a ceiling effect in parents with < 2% scoring in the marginal and limited functional health literacy categories.

The NVS was able to differentiate caregivers across a range of scores with a wider distribution. This difference was also acknowledged in the validation study for the NVS; the developers found that the NVS was a better discriminator of health literacy skills at the higher end of the distribution with greater measure sensitivity.9 This effect was even more prominent in caregivers of young children as we have seen in this study. 6 The S-TOFHLA functions well to distinguish health outcomes in many adult populations, however, in our sample of younger adults, the TOFHLA did not function as well with little variability across the spectrum of scores. Others have noted that the TOFHLA may not differentiate as well in certain populations 8,14 such as parents. The S-TOFHLA was validated in adults of a median age of 44 years, whereas our study population had a median age of 32 years. Knowing that fewer parents have limited health literacy in a national sample in comparison to adults that do not have children under the age of 18 years, it is not surprising that the measurement of health literacy differs in this population.6 The younger age of parents, along with differences in health literacy-related tasks, has led others to develop measures specifically for parents (Parental Health Literacy Activities Task-PHLAT).14 However, given the length of administration time, the PHLAT has limited use in some research environments such as a clinic or emergency department settings. Rather, we have found the NVS to be efficient, yielding an array of scores in younger adults.

Potentially due to the tertiary nature of our facility, the educational attainment of our population may be greater than at other centers with over 60% obtaining education beyond high school. We found that the test performance does not vary in the caregivers with lower educational attainment. In fact, the S-TOFHLA performs similarly poor in the caregivers with high school education or less. The NVS, however, does classify caregivers across literacy levels in both lower and higher educational attainment groups. Showing appropriate measure characteristics for those caregivers with lower educational attainment, the NVS categorizes more caregivers in the lower literacy levels. The NVS does categorize some caregivers as adequate health literacy among those with lower educational attainment, appropriately reflecting the characteristic of health literacy as a concept beyond that of literacy attainment or grade level achievement.

Another important aspect of measure evaluation, predictive ability, was investigated in this study. The NVS has shown predictive ability in a study of emergency department utilization whereas the S-TOFHLA did not. Others have found the NVS to distinguish health outcomes in patients, including diabetes,15 obesity,16 health system navigation,17 medication dosing and understanding,18,19 and use of mHealth,20 Additionally, the NVS has been used to assess health literacy in adolescents.15,21,22 As in our study, another study found that the NVS performed superiorly in detecting a relationship between limited health literacy and a health outcome (knowledge of appropriate antibiotic use) whereas the S-TOFHLA did not.23

Limitations

This study is limited to a single center and to caregivers willing to participate in the study, limiting interpretation of the findings. Additionally, no measures of cognitive function were administered alongside these measures to understand the relationship between cognitive functioning along with health literacy. Future research across multiple sites with parents may help to elucidate the utility of these measures and administering with other cognitive testing batteries would create a better understanding of the cognitive abilities of parents and how this relates to these health literacy measures. Our population may have differed from the general population, with over 60% of caregivers obtaining training beyond high school, which may artificially have lowered the prevalence estimate of limited health literacy on the S-TOFHLA. However, given that the NVS was able to detect health outcomes in this population, it is more likely that the NVS was more sensitive for health literacy abilities in a younger population of parents.

The measurement of health literacy is complex given the broad array of skills attributed to the concept including understanding and interpreting health information as well as decision-making regarding health.1 Both of the tests in this study are limited and reflect the nature of the existing tests of health literacy; both are measures of print, document, and quantitative literacy skills applied to health materials.

Conclusion

Though validated using the S-TOFHLA as a gold-standard, the NVS functions differently in younger adult populations such as parents or guardians of young children. The tests should not be considered equivalent in all populations. The tests likely measure the same constructs including document and quantitative literacy skills, however, the NVS appears to be a more difficult measure of these constructs. Across all health literacy levels, NVS serves as a more sensitive discriminator in caregivers of children. Additionally, the NVS has shown measure predictive ability for differences in health outcomes in this study and others. The NVS should be considered for use when measuring health literacy in adults with a younger median age, such as parents or caregivers of young children.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This publication was partially supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number 8UL1TR000055.

Abbreviations

- CSHCN

Children with Special Health Care Needs

- ED

Emergency department

- NVS

Newest Vital Sign

- S-TOFHLA

Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults

- OR

Odds Ratio

- AOR

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- IRR

Incidence Rate Ratio

- aIRR

Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio

Footnotes

Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Conflicts of Interest: No author has conflicts of interest and there are no corporate sponsors of this research.

References

- 1.Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, et al., editors. Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. 1. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar D, Sanders L, Perrin EM, et al. Parental understanding of infant health information: Health literacy, numeracy, and the parental health literacy activities test (PHLAT) Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(5):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janisse HC, Naar-King S, Ellis D. Brief report: Parent’s health literacy among high-risk adolescents with insulin dependent diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(4):436–440. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tran TP, Robinson L, Keebler J, Walker R, Wadman M. Health literacy among parents of pediatric patients. The western journal of emergency medicine. 2008;9(3):130–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin HS, Johnson M, Mendelsohn AL, Abrams MA, Sanders LM, Dreyer BP. The health literacy of parents in the united states: A nationally representative study. Pediatrics. 2009;124 (Suppl 3):S289–98. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1162E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrison AK, Schapira MM, Gorelick MH, Hoffmann RG, Brousseau DC. Low caregiver health literacy is associated with higher pediatric emergency department use and non-urgent visits. Acad Pediatr. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.01.004. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson J, Baker DW. In search of ‘low health literacy’: Threshold vs. gradient effect of literacy on health status and mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(9):1335–41. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss B, Mays M, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The newest vital sign. Annals of family medicine. 2005;3(6):514. doi: 10.1370/afm.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeAngelis C, Fosarelli P, Duggan AK. Use of the emergency department by children enrolled in a primary care clinic. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1985;1(2):61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mistry RD, Brousseau DC, Alessandrini EA. Urgency classification methods for emergency department visits: Do they measure up? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(12):870–874. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31818fa79d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mistry RD, Cho CS, Bilker WB, Brousseau DC, Alessandrini EA. Categorizing urgency of infant emergency department visits: Agreement between criteria. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(12):1304–1311. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar D, Sanders L, Perrin EM, et al. Parental understanding of infant health information: Health literacy, numeracy, and the parental health literacy activities test (PHLAT) Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(5):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassan K, Heptulla RA. Glycemic control in pediatric type 1 diabetes: Role of caregiver literacy. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):e1104–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chari R, Warsh J, Ketterer T, Hossain J, Sharif I. Association between health literacy and child and adolescent obesity. Patient Educ Couns. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jimenez ME, Barg FK, Guevara JP, Gerdes M, Fiks AG. The impact of parental health literacy on the early intervention referral process. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(3):1053–1062. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin HS, Mendelsohn AL, Fierman A, van Schaick L, Bazan IS, Dreyer BP. Use of a pictographic diagram to decrease parent dosing errors with infant acetaminophen: A health literacy perspective. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(1):50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin HS, Mendelsohn AL, Nagin P, van Schaick L, Cerra ME, Dreyer BP. Use of active ingredient information for low socioeconomic status parents’ decision-making regarding cough and cold medications: Role of health literacy. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(3):229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gazmararian JA, Yang B, Elon L, Graham M, Parker R. Successful enrollment in Text4Baby more likely with higher health literacy. J Health Commun. 2012;17 (Suppl 3):303–311. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.712618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Driessnack M, Chung S, Perkhounkova E, Hein M. Using the “newest vital sign” to assess health literacy in children. J Pediatr Health Care. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warsh J, Chari R, Badaczewski A, Hossain J, Sharif I. Can the newest vital sign be used to assess health literacy in children and adolescents? Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2013 doi: 10.1177/0009922813504025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunn-Navarra AM, Stockwell MS, Meyer D, Larson E. Parental health literacy, knowledge and beliefs regarding upper respiratory infections (URI) in an urban latino immigrant population. J Urban Health. 2012;89(5):848–860. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9692-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]