Abstract

We describe the design, synthesis and SAR profiling of a series of novel combretastatin–nocodazole conjugates as potential anticancer agents. The thiophene ring in the nocodazole moiety was replaced by a substituted phenyl ring from the combretastatin moiety to design novel hybrid analogues. The hydroxyl group at the ortho position in compounds 2, 3 and 4 was used as the conformationally locking tool by anticipated six-membered hydrogen bonding. The bioactivity profiles of all compounds as tubulin polymerization inhibitors and as antiproliferative agents against the A-549 human lung cancer cell line were investigated Compounds 1 and 4 showed μM IC50 values in both assays.

Keywords: Tubulin binding, Nocodazole, Colchicine, Anticancer

Microtubules are long, hollow, cylindrical biopolymers composed of 13 protofilaments. Their subunit protein is the αβ-tubulin heterodimer. In addition, many other proteins bind to microtubules, such as microtubule-associated proteins and numerous motor proteins. Moreover, many chemically diverse natural products and their analogues bind to tubulin or to microtubules.1 Many of these compounds, as well as a variety of synthetic molecules bind to the colchicine binding domain of tubulin at the heterodimer interface between α- and β-tubulin and affect polymerization dynamics.2

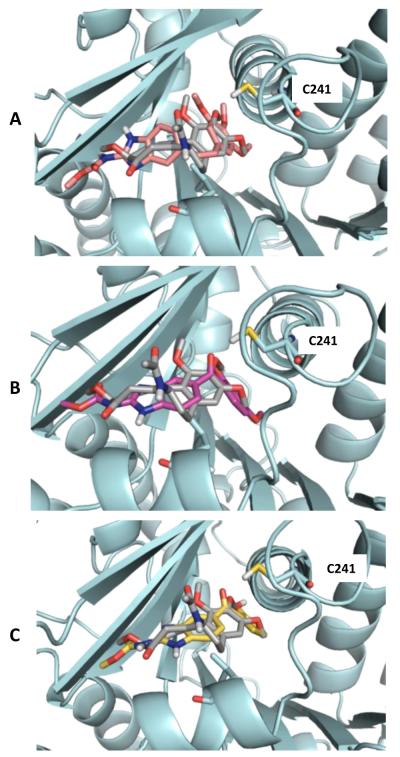

Among the various microtubule-interacting agents that bind to the colchicine site, nocodazole and combretastatin A-4 (CA-4) (Fig. 1) have attracted considerable attention due to their simplicity in structure and their potent antiproliferative activity. Nocodazole has potent antitubulin activity, thus affecting the microtubule component of the cytoskeleton, and it is one of the potent members of the benzimidazole family.3 Analogues of nocodazole with diverse structural modifications and variation in biological activity have been reported.4 Combretastatins are another potent class of antimitotic agents known to interact with the colchicine binding site of tubulin.5 Among the combretastatin analogues, CA-4 is one of the most potent tubulin polymerization inhibitors, and its derivative CA-4 phosphate6 is presently in clinical trials for the treatment of cancer. A possible approach to novel analogues is to design structures imparting conformational restriction in nocodazole and combretastatin to improve potentially their bio-activity profiles.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of colchicine, nocodazole and combretastatin A-4.

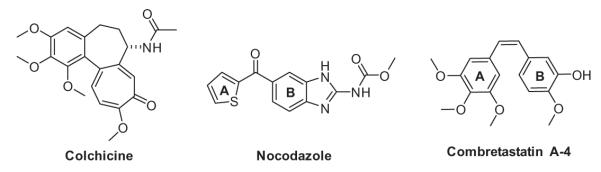

Herein, we describe the design and synthesis of novel hybrid nocodazole analogues (1–4) as potential tubulin binding agents (Fig. 2). SAR studies reveal that the A ring and cisoid conformation of CA-4 are fundamental for tubulin binding,7 hence the design strategy to develop analogue 1 was to replace the B ring of CA-4 with the B ring of nocodazole. The constrained nocodazole hybrid analogues (2–4) were designed using a conformational restriction strategy through hydrogen bonding. The analogue 2 was designed by introducing the hydroxyl group at the ortho position and the hydrophobic methoxy (OCH3) group at the para position on the aromatic ring A of nocodazole. We anticipated that the hydroxyl group would be involved in six-membered intramolecular hydrogen bonding, while the methoxy group would provide hydrophobic interactions. Also, the hydroxy group can effectively increase binding affinity owing to H-bonding interactions with protein amino acid residues, as described in the case of resveratrol.8 Analogue 3 is a modification of analogue 2 obtained by replacing the hydrophobic para methoxy group in the aromatic ring of part A with a hydrophilic hydroxyl group. We have previously reported that the role of conformational restriction through hydrogen bonding in the case of tetrazole-tethered combretastatin analogues results in a mixed response in terms of bioactivity profile.9 The conformation of nocodazole can also be restricted by inserting a hydroxyl group on the A ring of nocodazole as in designed analogue 4.

Figure 2.

Molecular structures of designed nocodazole hybrid analogues.

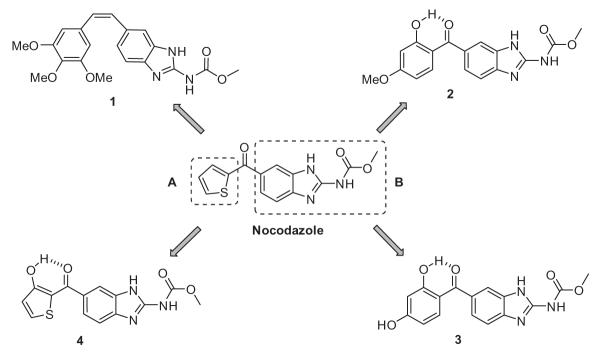

Synthesis of hybrid analogue 1 began with C–C coupling of aromatic acetylene 510 with 4-iodo-2-nitroaniline 611 under standard Sonogashira reaction conditions to afford 7 (Scheme 1). Compound 7 was initially subjected to controlled reduction of the triple bond functionality to cis-olefin functionality. However, this strategy did not yield a tangible result, regardless of best efforts. Therefore, the nitro functionality of 7 was subjected to reduction using Zn and ammonium formate to afford crude diamine. Subsequently, diamine acetylene was selectively reduced to the cis-olefin using Lindlar catalysis and quinoline to furnish 8. The intermediate 8 was quickly subjected to 1,3-bis(methoxycarbonyl)-2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea mediated cyclization to afford hybrid analogue 1.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (i) Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, CuI, Et3N, THF, rt, 12 h; (ii) (a) Zn, HCOONH4, MeOH, rt, 4 h, (b) Lindlar cat., H2, quinoline, 1 atm, MeOH, 4 h; (iii) 1,3-bis(methoxycarbonyl)-2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea, MeOH, PTSA, reflux, 10 h.

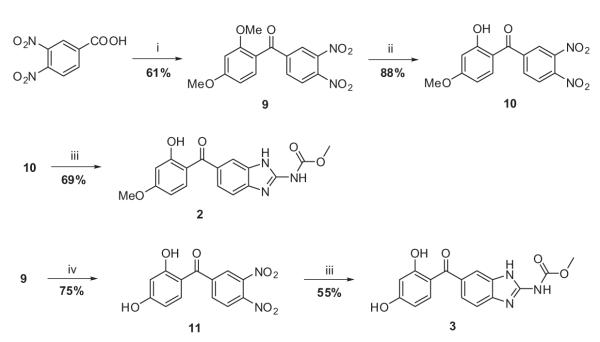

Synthesis of hybrid analogues 2 and 3 was started with Friedel–Crafts acylation of 1,3-dimethoxybenene (Scheme 2). The 3,4-dinitrobenzoic acid was converted to the corresponding acid chloride using SOCl2 at reflux condition. The electrophilic aromatic substitution of 1,3-dimethoxybenzene with 3,4-dinitrobenzoyl chloride in the presence of Lewis acid-TiCl4 furnished intermediate 9. The selective mono-demethylation of 9 was carried out using BBr3/DCM to yield 10. The nitro functionalities of 10 were reduced to the diamines under catalytic hydrogenation conditions, followed by 1,3-bis(methoxycarbonyl)-2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea mediated cyclization to afford the designed analogue 2. Furthermore, the extensive demethylation of 9 was carried out using excess BBr3/DCM at reflux condition for 48 h to furnish intermediate 11. The compound 11 was subjected to dinitro reduction, followed by cyclization using a similar protocol as described for 2, to afford analogue 3.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (i) (a) SOCl2, reflux, 12 h, (b) 1,3-dimethoxybenzene, TiCl4, DCM, reflux, 8 h; (ii) BBr3, dry DCM, reflux, 12 h; (iii) (a) H2, Pd/C, 60 psi, 12 h, (b) 1,3-bis(methoxycarbonyl)-2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea, MeOH, PTSA, reflux, 10 h; (iv) BBr3, dry DCM, reflux, 48 h.

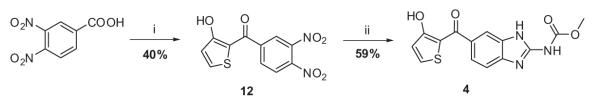

Aluminum chloride-mediated electrophilic aromatic acylation of the 3-methoxy thiophene and the 3,4-dinitrobenzoyl chloride furnished intermediate 12 (Scheme 3). Intermediate 12 was subjected to catalytic hydrogenation conditions to afford crude diamine, followed by 1,3-bis(methoxycarbonyl)-2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea mediated cyclization to furnish analogue 4.

Scheme 3.

Reagents and conditions: (i) (a) SOCl2, reflux, 12 h, (b) 3-methoxythiophene, AlCl3, dry DCM, reflux, 12 h; (ii) (a) H2, Pd/C, 60 psi, 12 h, (b) 1,3-bis(methoxycarbonyl)-2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea, MeOH, PTSA, reflux,10 h.

The novel designed hybrid nocodazole analogues (1–4) were evaluated for potential inhibition of tubulin assembly and for inhibition of the binding of [3H]colchicine to tubulin (Table 1), using CA-4 as a positive control. Analogues 1, 2 and 4 showed excellent activities as inhibitors of tubulin assembly, differing little from the activity observed with CA-4. The compounds were less active than CA-4 as inhibitors of colchicine binding to tubulin. Analogue 3 having two hydroxyl groups on the A ring was inactive as a tubulin polymerization inhibitor. The designed analogues were also examined for their cytotoxic activity against the A549 human lung cancer cell line, again using CA-4 as a positive control (Table 2). Compound 1 and 4 were most active with IC50 values of 12 and 6 μM, respectively, while compounds 2 and 3 showed no activity against this cell line.

Table 1.

Inhibition of tubulin polymerization and colchicine binding by compounds 1–4

| Compound | Inhibition of tubulin assembly;a IC50 (μM) ± SD |

Inhibition of colchicine binding;b% inhibition ± SD; 5 μM inhibitor |

|---|---|---|

| CA-4 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 99 ± 0.06 |

| 1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 39 ± 0.5 |

| 2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 38 ± 2 |

| 3 | >20 | – |

| 4 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 56 ± 4 |

Inhibition of tubulin polymerization (tubulin was at 10 μM).

Inhibition of [3H]colchicine binding (tubulin, colchicine, and tested compounds were at 1, 5, and 5 μM, respectively).

Table 2.

IC50a values (μM) of compounds 1–4

| Analogues | A549 Lung cancer cell line |

|---|---|

| CA-4 | 0.28 ± 0.05 |

| 1 | 12 ± 1.35 |

| 2 | >100 |

| 3 | >100 |

| 4 | 6 ± 2.8 |

The data are expressed as the mean ± SE from the dose–response curves of at least three experiments.

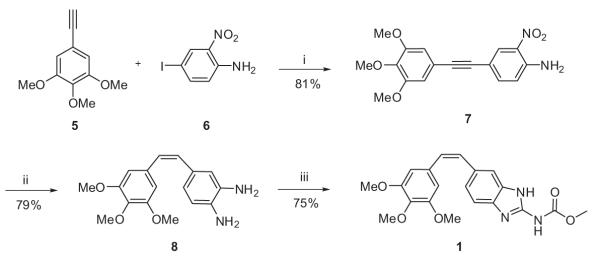

Using the 1SA0 crystal structure of αβ-tubulin as a template,12 compounds 1–4 were docked into the colchicine binding site to provide a molecular basis for understanding their activity and concomitantly to explain the lesser activity of 3.

The docking model comprising the receptor protein with compound 1, 2 and 4 indicates that these ligands get oriented in active site fitted conformation which is almost similar to colchicine (Fig. 3). Compounds 1, 2 and 4 have hydrophobic moieties after modification in nocodazole (non-conserved part) which was predominantly responsible for obtaining colchicine like conformation in active site which was further corroborated by non-covalent interactions. However, in case of compound 3 the hydrophilic moiety, in non-conserved structure of nocodazole, leads to different orientation in active site of receptor protein having weak interactions in comparison to colchicine.13

Figure 3.

Predicted binding model from Schrodinger, binding model of compound 1(A), 2 (B) and 4 (C) overlaid with that of colchicine in the binding site on β-tubulin, which is shown in cyan blue. The ligands are rendered in stick with oxygen, nitrogen and polar hydrogen atom colored red, blue and white, respectively. The carbon atoms are colored raspberry, magenta, yellow and gray for compound 1, 2, 4, and colchicine, respectively.

In conclusion, a series of novel nocodazole analogues were designed and synthesized and their bio-activity profile as tubulin polymerization inhibitors and as antiproliferative agents against the A549 human cancer cell line were investigated. This study demonstrates a designed strategy to synthesize novel hybrid analogues of nocodazole. The reduced potency of compounds 2 and 3 have shown the importance of hydrophobic interactions in Ring A for better inhibition of tubulin assembly and colchicine binding and hence for potential anticancer activity. There is ample scope for further modification of these analogues and application of such a strategy elsewhere.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

S.S.K. and G.S.J. are thankful to CSIR, New Delhi, for a research fellowship. G.J.S. thanks CSIR-Biodiversity programme (BSC-0120) for funding this project.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.03.019.

References and notes

- 1(a).Jordan A, Hadfield JA, Lawrence NJ, McGown AT. Med. Res. Rev. 1998;18:259. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(199807)18:4<259::aid-med3>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dixon N, Wong LS, Geerlings TH, Micklefield J. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007;24:1288. doi: 10.1039/b616808f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2(a).Hastie SB. Pharmacol. Ther. 1991;51:377. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(91)90067-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Skoufias DA, Wilson L. Biochemistry. 1992;31:738. doi: 10.1021/bi00118a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nguyen TL, McGrath C, Hermone AR, Burnett JC, Zaharevitz DW, Day BW, Wipf P, Hamel E, Gussio R. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:6107. doi: 10.1021/jm050502t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Den Bossche H, Rochette F, Hörig C. Advances in Pharmacology and Chemotherapy. Vol. 19. Academic Press; New York: 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4(a).Kruse LI, Ladd DL, Harrsch PB, McCabe FL, Mong S-M, Faucette L, Johnsons R. J. Med. Chem. 1989;32:409. doi: 10.1021/jm00122a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ross ST, Kruse LI, Kingsbury WD, Erhard KF, Harrsch PB, Debrosse CW, Webb RL, Mccabe FL, Mong S-M, Johnson RK. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1989;4:363. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rashid M, Husain A, Siddiqui AA, Mishra R. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;62:785. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pettit G, Cragg GM, Herald DL, Schmidt JM, Lohavanijaya P. Can. J. Chem. 1982;60:1374. [Google Scholar]

- 6(a).Pettit GR, Temple C, Narayanan VL, Varma R, Simpson MJ, Boyd MR, Rener GA, Bansal N. Anticancer Drug Des. 1995;10:299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dark GG, Hill SA, Prise VE, Tozer GM, Pettit GR, Chaplin DJ. Cancer Res. 1829;1997:57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7(a).Blanch NM, Chabot GG, Quentin L, Scherman D, Bourg S, Dauzonne D. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;54:22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Alvarez R, Alvarez C, Mollinedo F, Sierra BG, Medarde M, Pelaez R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:6422. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pettit GR, Rhodes MR, Herald DL, Hamel E, Schmidt JM, Pettit RK. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:4087. doi: 10.1021/jm0205797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murias M, Handler N, Erker T, Pleban K, Ecker G, Saiko P, Szekeres T, Jager W. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:5571. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jedhe GS, Paul D, Gonnade RG, Santra MK, Hamel E, Nguyen TL, Sanjayan GJ. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:4680. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawrence NJ, Ghani FA, Hepworth LA, Hadfield JA, McGown AT, Pritchard RG. Synthesis. 1999;9:1656. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emmanuvel L, Shukla RK, Sudalai A, Gurunath S, Sivaram S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:4793. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ravelli RB, Gigant B, Curmi PA, Jourdain I, Lachkar S, Sobel A, Knossow M. Nature. 2004;428:198. doi: 10.1038/nature02393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.See Supplementary material for overlaid image of compound 3 with colchicine in tubulin.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.