Key Points

In this phase 1b study, obinutuzumab plus FC or B had acceptable safety, with infusion reactions the most common adverse event.

Obinutuzumab plus FC or B showed promising clinical activity in the initial treatment of CLL, with no relapses to date.

Abstract

Obinutuzumab is a type 2, glycoengineered, anti-CD20 antibody recently approved with chlorambucil for the initial therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). In this nonrandomized, parallel-cohort, phase 1b, multicenter study, we explored the safety and preliminary efficacy of obinutuzumab-bendamustine (G-B) or obinutuzumab fludarabine cyclophosphamide (G-FC) for the therapy of previously untreated fit patients with CLL. Patients received up to 6 cycles of G-B (n = 20) or G-FC (n = 21). The primary end point was safety, with infusion-related reactions (88%, grade 3-4 20%) being the most common adverse event and grade 3-4 neutropenia in 55% on G-B and 48% on G-FC. Mean cycles completed were 5.7 for G-B and 5.1 for G-FC, with 2 and 7 early discontinuations, respectively. The objective response rate (ORR) for G-B was 90% (18/20) with 20% complete response (CR) and 25% CR with incomplete marrow recovery (CRi). The ORR for G-FC was 62% (13/21), with 10% CR and 14% CRi, including 4 patients not evaluable. With a median follow-up of 23.5 months in the G-B cohort and 20.7 months in the G-FC cohort, no patient has relapsed or died. We conclude that obinutuzumab with either B or FC shows manageable toxicity and has promising activity. This study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01300247.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a chronic leukemia of adults, which has a widely variable disease course. Historically, therapy had been primarily palliative, but more potent regimens that included the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (FC) were found to improve patient survival.1-3 The subsequent advent of bendamustine (B) added another effective chemotherapy backbone, which has also been frequently combined with rituximab.4-6 This substantial efficacy and safety of rituximab in combination with chemotherapy has validated the use of monoclonal antibodies directed against CD20 as effective treatment of patients with CLL.

Obinutuzumab (previously known as GA101) is a humanized immunoglobulin G1 antibody targeting CD20, which was developed as a type 2 antibody and glycoengineered for enhanced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and phagocytosis.7-9 Like other type 2 antibodies, obinutuzumab does not stabilize CD20 in lipid rafts, and therefore it induces less complement-dependent cytotoxicity than type 1 antibodies. Obinutuzumab does induce stronger homotypic aggregation of B cells, resulting in greater direct cell death. In addition, the Fc segment of obinutuzumab is glycoengineered and is more effective at eliciting antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity than rituximab,8 as has been demonstrated with CLL cells in vitro.10

In phase 1 studies of obinutuzumab in patients with CLL and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, no dose-limiting toxicities were observed at obinutuzumab doses up to 2000 mg.11,12 The primary toxicity was infusion-related reaction, including some grade 3-4 events, which were manageable.11,12 Treatment-related neutropenia also appeared to be more common with obinutuzumab than with other anti-CD20 antibodies.11-13 The CLL11 trial of the German CLL Study Group compared therapy with chlorambucil alone (Clb) or with rituximab (R-Clb) or obinutuzumab (G-Clb) in previously untreated patients with CLL and comorbid medical conditions.14 Six patients were treated with G-Clb in a safety run-in, in which G-Clb was found to have an acceptable safety profile, albeit with the expected manageable infusion reactions and neutropenia. In this run-in, G-Clb produced rapid B-cell depletion in peripheral blood in these 6 CLL patients.13

The CLL11 study demonstrated that treatment of patients with G-Clb improved the objective response rate (ORR), complete response (CR) rate, rate of minimal residual disease–negative CR, and progression-free survival (PFS) compared with treatment with Clb alone.14 These results served as the basis for US Food and Drug Administration approval of the G-Clb regimen for the initial therapy of patients with CLL. Subsequently, updated data showed an overall survival (OS) benefit for G-Clb compared with Clb alone (9% deaths vs 20% for Clb; hazard ratio = 0.41; P = .002). In the same analysis, the comparison of the outcome of patients treated with G-Clb to those treated with R-Clb showed that G-Clb–treated patients had an improved ORR, CR rate, rate of minimal residual disease–negative CR, and PFS, which improved from 16.3 months with R-Clb to 26.7 months with G-Clb.14

Given the superior efficacy of treatment with obinutuzumab and Clb compared with rituximab and Clb, there was interest in evaluating the activity of obinutuzumab with other chemotherapies, such as FC or B. The study reported here, GALTON (NCT01300247), is the first study to assess the safety and preliminary efficacy of obinutuzumab in combination with FC or B in a nonrandomized, parallel-group, phase 1b study in previously untreated patients with CLL who were fit for chemoimmunotherapy.

Patients and methods

Study design

GALTON was an open-label, parallel-arm, nonrandomized, multicenter, phase 1b study that investigated the safety and preliminary efficacy of either the combination of obinutuzumab plus FC (G-FC) or the combination of obinutuzumab plus B (G-B) given every 28 days for up to 6 cycles to previously untreated patients with CLL who required treatment and were considered fit for chemoimmunotherapy by the enrolling investigator. Treatment arm assignment was on a per-center basis. Each center decided which chemotherapy backbone (FC or B) it would use for all its patients.

The primary end point was safety and tolerability of obinutuzumab with chemotherapy. Secondary end points included response rates, duration of response, PFS, OS, pharmacokinetics, peripheral B-cell depletion, and recovery. A total of 40 patients were planned to evaluate the safety of obinutuzumab in combination with FC or B. With 40 patients, there was at least an 87% chance of observing an adverse event with a true incidence of ≥5%. Within each chemotherapy regimen, the chance of observing an adverse event with a true incidence of ≥10% was at least 88%.

Patient population

Eligible patients were older than 18 years and had previously untreated CLL with an indication for treatment according to the 2008 International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia guidelines15 and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-2. Exclusion criteria included any prior therapy, transformation of CLL to an aggressive B-cell malignancy, and active bacterial or viral infections or positive serology for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or HIV. To enroll, patients had to have adequate renal function (creatinine clearance >60 mL/min for G-FC), liver function (alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase ≤2.5 × upper limit of normal), and marrow function (platelet ≥75 000 cells/mm3, hemoglobin >9 g/dL, and absolute neutrophil count >1.5 × 109 cells/mm3, unless due to underlying CLL). All patients provided written informed consent. This investigation was conducted according to Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice principles, and institutional review boards at each investigational site approved the protocol. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01300247.

Treatment

Patients received treatment with either G-FC or G-B. Obinutuzumab was administered IV (100 mg on day 1, 900 mg on day 2, and 1000 mg on day 8 and day 15 of cycle 1; 1000 mg on day 1 of cycles 2-6) with either FC (fludarabine 25 mg/m2 IV and cyclophosphamide 250 mg/m2 IV on days 2-4 of cycle 1, then days 1-3 of cycles 2-6) or B (90 mg/m2 IV on days 2-3 of cycle 1, then days 1-2 of cycles 2-6). Each cycle was 28 days. All patients received prophylaxis for infusion related reactions (IRRs) that included acetaminophen and an antihistamine such as diphenhydramine before each obinutuzumab infusion. In addition, premedication with a highly potent corticosteroid (eg, 100 mg IV prednisolone or equivalent, not including hydrocortisone) was mandatory for the first dose of obinutuzumab (100 mg on day 1, 900 mg on day 2). Allopurinol or rasburicase for tumor lysis syndrome prophylaxis, as well as Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis and antiviral prophylaxis, was recommended. Growth factor support, as primary prophylaxis, was permitted at the investigator’s discretion. Patients who required a >14-day treatment delay for any reason were mandated to discontinue therapy.

Assessments

Adverse events were reported per the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0. IRRs were broadly defined as any adverse event related to obinutuzumab that occurred during or within 24 hours of the end of the infusion. Serum chemistry and blood counts were performed weekly. Investigators assessed patients for response and progression on the basis of peripheral blood counts, physical examination, and marrow aspirate/biopsy results. Radiology reports from a posttreatment computed tomography (CT) scan were required to designate a CR or partial response. Clinical response was assessed no earlier than 2 months after the last dose of study treatment. IGHV, ZAP-70 by flow cytometry, and fluorescence in situ hybridization were all assessed by a central laboratory.

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

Pharmacokinetic (PK) samples were collected before, immediately after, and 30 minutes and 4 hours after the first dose of obinutuzumab in cycle 1. Additional PK samples were collected before and after obinutuzumab infusions on days 8 and 15 in cycle 1 and day 1 of cycles 2, 4, and 6. The PK data collected in this study have been compared with a robust population PK model of obinutuzumab in 590 patients (254 CLL and 336 non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients) using nonlinear mixed-effects modeling (with NONMEM software).

Whole-blood samples to determine B-cell depletion and recovery were collected on a schedule similar to that planned for the PK analysis. B-cell depletion was defined as <70 CD19-positive cells per μL and could occur only after at least 1 dose of study drug had been administered. B-cell recovery was defined as recovery of CD19-positive cells to ≥70/μL in a patient who was previously B-cell depleted. Also, anti-therapeutic antibodies to obinutuzumab were assessed prior to administration of obinutuzumab on day 1 of cycles 1, 3, and 5 and at 2 and 6 months after the last infusion of obinutuzumab.

Statistical analysis

Treatment regimen assignment was on a per-center basis and not randomized, and all results are presented for the G-FC and G-B treatment regimens separately without formal comparison. All patients who received any amount of study treatment were included in the safety analysis and were considered potentially evaluable for efficacy. A safety run-in analysis that included data from the first 3 patients in each study arm treated through day 28 was performed by the sponsor’s internal monitoring committee before exposing additional patients to the combination of obinutuzumab plus chemotherapy (FC or B). The primary analysis was based on the intent-to-treat population and was conducted in January 2013 (median follow-up time was 10.7 months for the G-FC cohort and 13.6 months for the G-B cohort), and safety and PFS data were updated in January 2014 (median follow-up time was 20.7 months for the G-FC cohort, 23.5 months for the G-B cohort, and 22.1 months overall). The analysis of preliminary efficacy was based on the end-of-treatment response assessment, which took place approximately 2 months after the last infusion of study treatment and not earlier than 51 days after study treatment (or 3 months for those patients who completed a marrow examination to confirm CR). Patients with missing or no response assessments were classified as nonresponders. Quantitative variables are summarized as median (range) or median (95% confidence interval [CI]). ORR and individual response categories are summarized in proportions, with the corresponding 95% CI using the Clopper Pearson Method. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics: G-B cohort

Twenty patients were enrolled in the G-B cohort, with a median age of 62 (42-80) years (Table 1). The median time from diagnosis to this first therapy was 32 months (range, 0.4-337). No patients had CLL cells with 17p deletion, whereas 2 patients had CLL cells with 11q deletion (11%). Forty-four percent of patients had CLL cells that used unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) genes. Approximately half the patients had B symptoms prior to therapy. Upon enrollment, 30% of the patients had advanced stage disease and 7 patients (35%) had bulky lymphadenopathy (at least 1 lymph node ≥5 cm).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| G-FC (n = 21) | G-B (n = 20) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 58 (25-72) | 62 (42-80) |

| Male, n (%) | 17 (81) | 15 (75) |

| Median time from diagnosis, mo (range) | 24 (3-108) | 32 (0.4-337) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 5 (24) | 3 (15) |

| 1 | 16 (76) | 17 (85) |

| Presence of B symptoms, n (%) | 11 (52) | 12 (60) |

| Rai stage III/IV, n (%) | 7 (33) | 6 (30) |

| Median lymphocyte count, 109/L (range) | 70 (5-334) | 42 (4-207) |

| Median SPD of target LN, mm2 (range) | 4 193 (215-16 080) | 3 094 (600-23 137) |

| Β2 microglobulin ≥3.5 mg/L, n (%) | 10/19 (53) | 12/16 (75) |

| Serum thymidine kinase ≥140 DU/L, n (%) | 6/7 (86) | 6/8 (75) |

| Cytogenetics, n (%) | n = 17 | n = 18 |

| 17p− | 1 (6) | 0 |

| 11q− | 4 (24) | 2 (11) |

| Trisomy 12 | 3 (18) | 5 (28) |

| 13q− | 5 (29) | 6 (33) |

| Normal karyotype | 4 (24) | 5 (28) |

| IGHV unmutated, n (%) | 9/20 (45) | 8/18 (44) |

| ZAP70 expression ≥20%, n (%) | 14/19 (74) | 11/18 (61) |

| CD38 expression ≥30%, n (%) | 8/19 (42) | 5/18 (28) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LN, lymph node; SPD, sum of the products of the greatest perpendicular diameters.

Therapy and patient disposition: G-B cohort

The median number of treatment cycles received was 6 (range, 1-6). The median delivered cumulative dose of obinutuzumab was the full planned 8-g dose, and the median delivered dose of B was 92% of that planned. Seventeen of 20 patients completed the full planned 6 cycles of therapy. Two patients discontinued with grade 3 neutropenia, 1 after cycle 2 day 1 (despite prophylactic filgrastim and pegfilgrastim administration) and 1 after cycle 5 day 1 (Table 2). Of 120 planned cycles of therapy, 113 cycles were administered, including 14 dose delays of up to 14 days. Fifteen patients (75%) on this arm received myeloid growth factor at some point during therapy, for either prophylaxis or therapy of neutropenia.

Table 2.

Adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation

| Patients, n (%) | G-FC (n = 21) | G-B (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients with at least 1 adverse event leading to discontinuation | 7 (33) | 2 (10) |

| Overall total number of events | 9 | 2 |

| Neutropenia | 3 (15) | 2 (10) |

| Pancytopenia | 1 (5) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 (10) | 0 |

| ALT/AST increased | 2 (10) | 0 |

| Cellulitis | 1 (5) | 0 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

Safety: G-B cohort

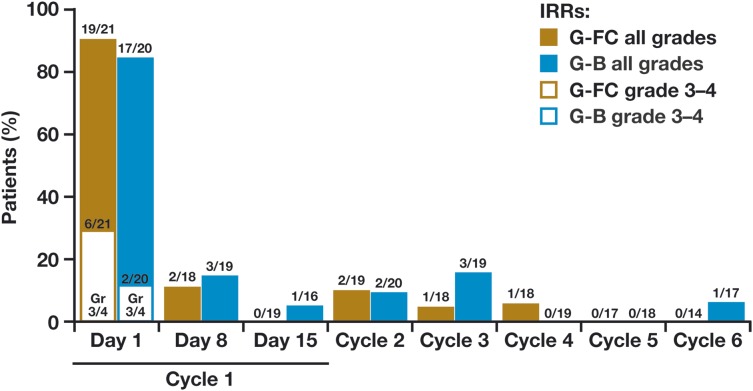

Serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported in 9 of 20 (45%) patients, with 2 events of febrile neutropenia (10%) and 1 event of infection (grade 3 skin infection; 5%). Seventeen of 20 (85%) patients experienced a grade 3-4 adverse event (Table 3). Sixty percent of patients experienced at least 1 grade 3-4 hematologic event, including 11 (55%) patients with neutropenia (including 2 [10%] patients with febrile neutropenia), 10% with thrombocytopenia, and 5% with anemia. One patient was diagnosed with a second malignancy, a squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. In the G-B cohort, 90% of patients had an IRR, including 4 IRR-related SAEs, 2 of which were grade 2, 1 grade 3, and 1 grade 1 fever that occurred 24 hours after completing the obinutuzumab infusion; 17 additional patients had a grade 1-2 infusion reaction. Most IRRs occurred with the first dose, and no grade 3-4 IRRs were observed after the first dose (Figure 1). Two patients in the G-B cohort also had early grade 3 elevation in hepatic transaminases, 1 on cycle 1 day 3 and 1 on cycle 1 day 14, despite no reported IRR events. Neither of these patients had evidence of infection with a hepatitis virus.

Table 3.

Selected adverse events

| Patients, n (%) | G-FC (n = 21) | G-B (n = 20) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | Grade 3-4 | All grades | Grade 3-4 | |

| All AEs | 21 (100) | 18 (86) | 20 (100) | 17 (85) |

| Hematologic AE | ||||

| Neutropenia | 6 (29) | 6 (29) | 10* (50) | 10 (50) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 4 (19) | 4 (19) | 2* (10) | 2 (10) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 4 (19) | 4 (19) | 4 (20) | 2 (10) |

| Anemia | 5 (24) | 3 (14) | 3 (15) | 1 (5) |

| Infections | 11 (52) | 4 (19) | 9 (45) | 1 (5) |

| Tumor lysis syndrome | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Laboratory investigations | ||||

| Elevation in hepatic transaminases | 4 (19) | 4 (19) | 2 (10) | 2 (10) |

The total number of patients treated with G-B who experienced grade 3-4 neutropenia was 11 (55%), as 1 patient was reported to have both febrile neutropenia and grade 3-4 neutropenia.

Figure 1.

Obinutuzumab infusion-related adverse events by cycle.

Efficacy: G-B cohort

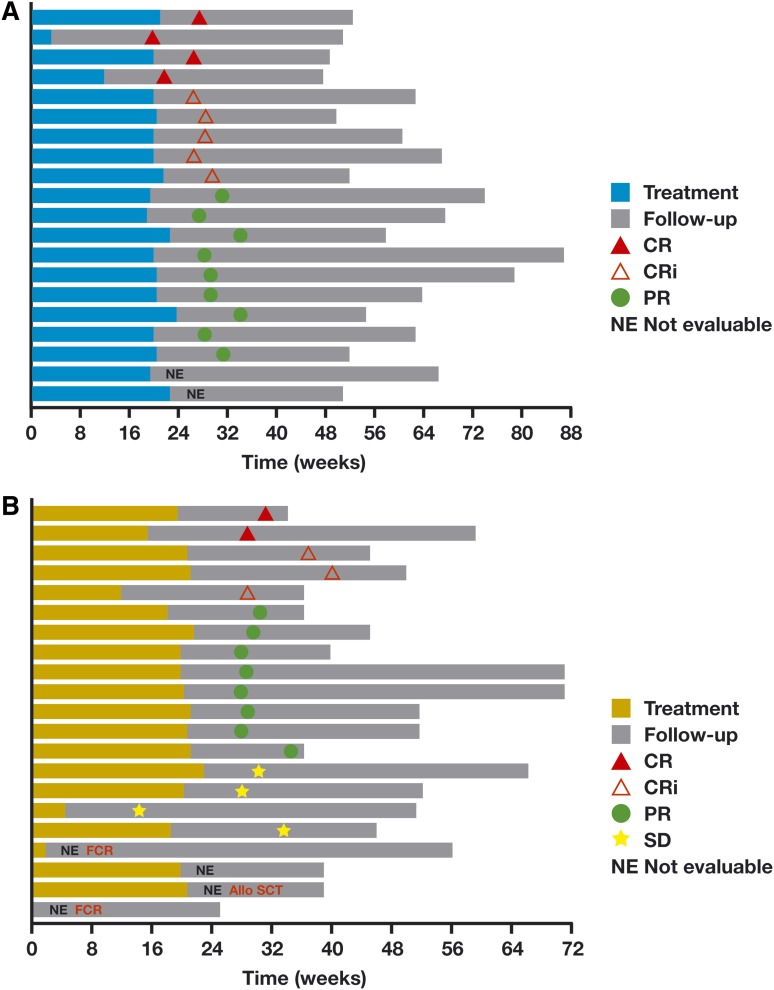

Objective response was observed in 18 of 20 (90%) patients, with 20% CRs and 25% CR with incomplete marrow recovery (CRi) (Table 4). All 20 patients who received any therapy were included in the denominator, which included 2 patients who were not evaluable due to absence of an end of treatment CT and an evaluation that was too early. All 14 patients who underwent end-of-treatment marrow evaluation showed no evidence of disease on pathological review. With a median follow-up of 23.5 months, no patients have progressed or died (Figure 2A). After the data cutoff, 1 patient who reportedly had stable CLL and prostate cancer died of pneumonitis and respiratory failure while in hospice.

Table 4.

End-of-treatment overall response rate

| Patients, n (%) | G-FC (n = 21) | G-B (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| ORR (CR + CRi + PR) | 13 (62) | 18 (90) |

| CR | 2 (10) | 4 (20) |

| CRi | 3 (14) | 5 (25) |

| PR | 8 (38) | 9 (45) |

| SD | 4 (19) | 0 |

| PD | 0 | 0 |

| Not evaluable* | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Missing† | 3 (14) | 1 (5) |

PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Not evaluable. G-FC (n = 1) and G-B (n = 1): end-of-treatment CT not evaluable.

Missing. G-FC: response assessed too early (n = 1); early treatment discontinuation due to adverse event (n = 2). G-B: response assessed too early (n = 1).

Figure 2.

Plots of duration of time on therapy and response for each patient. (A) Obinutuzumab plus B. (B) Obinutuzumab plus FC. Allo SCT, allogeneic stem cell transplantation; FCR, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide plus rituximab.

Patient characteristics: G-FC cohort

Twenty-one patients were enrolled on the G-FC cohort, with a median age of 58 years (range, 25-72) (Table 1). The median time from diagnosis to this first therapy was 24 months (range, 3-108). Five patients (30%) had CLL cells with either 17p or 11q deletion, and 45% of patients had CLL that used unmutated IGHV. Upon enrollment, 52% of patients had B symptoms, one-third had advanced-stage disease, and 8 patients (38%) had bulky lymphadenopathy (at least 1 lymph node ≥5 cm).

Therapy and patient disposition: G-FC cohort

The median number of treatment cycles was 6 (range, 1-6). The median delivered cumulative dose of obinutuzumab was the full planned 8-g dose. The median delivered doses of both fludarabine and cyclophosphamide were 92% of planned. Fourteen patients completed the full planned 6 cycles of therapy, with 3 additional patients completing 5 cycles (Table 2). Of 126 planned cycles of therapy, 106 were administered, including 9 dose delays up to 14 days. Two patients discontinued during cycle 1, 1 after a single 100 mg dose of obinutuzumab that resulted in grade 4 elevation in hepatic transaminases that mandated protocol withdrawal and the second after developing neutropenia complicated by cellulitis, without having received prophylactic myeloid growth factor. An additional patient discontinued in cycle 2 with the development of pancytopenia, also without prophylactic myeloid growth factor, and a fourth patient after cycle 4 with thrombocytopenia (Table 2). During cycle 5, 3 patients discontinued, 1 with grade 3 thrombocytopenia and 2 with neutropenia. Thirteen patients (62%) on this arm received growth factor at any point, for either prophylaxis or therapy of neutropenia.

Safety: G-FC cohort

SAEs were reported in 6 of 21 (29%) patients, with 3 events of febrile neutropenia (19%), 1 event of neutropenia (5%), and 3 events of infection (1 each appendicitis, cellulitis, and pneumonia; 14%). Eighty-six percent of patients experienced a grade 3-4 adverse event (Table 3). Forty-three percent of patients experienced at least 1 grade 3-4 hematologic event, including 8 (21%) patients that had neutropenia (including 4 [19%] patients with febrile neutropenia) and 14% each with anemia or thrombocytopenia. Fifty-two percent of patients had at least 1 infection-related adverse event, and 5 grade 3-4 infections (19%) were seen in 4 patients, including the above 3 plus a tooth infection and a paronychia. No patient in this arm was diagnosed with a second malignancy during treatment or follow-up. On the G-FC regimen, 91% of patients had an IRR, including 6 of 21 who had a grade 3-4 first infusion reaction. No patients had IRR-related SAEs. As in the G-B cohort, no grade 3-4 IRRs were observed after the first dose (Figure 1).

Four patients receiving G-FC experienced grade 3-4 elevation in hepatic transaminases, with 3 of the 4 developing this on cycle 1 day 2, after having received only the initial 100-mg obinutuzumab dose. Two of these four patients experienced a grade 2 IRR. These events were self-limited and without subsequent recurrence. None of these patients had evidence of infection with a hepatitis virus. The timing of these events suggests that they were related to the initial IRRs with obinutuzumab.

Efficacy: G-FC cohort

Objective response was observed in 13 of 21 (62%) patients, with 10% achieving CR and 14% obtaining a CRi (Table 4). All 21 patients who received any therapy were included in the denominator, which included 2 patients who discontinued study therapy in cycle 1 without a response evaluation, as well as a patient who missed the CT scan required for response assessment. One patient had a response evaluation that was prior to the time required by the study protocol. In addition, of the 4 patients said to have stable disease, 3 were designated as stable disease without undergoing the full response evaluation required to define response in the protocol. Only 1 stable-disease patient underwent a full response evaluation, which showed a 39% reduction in lymphadenopathy. Thus, the response rate data should be understood with the caveats of both small study numbers leading to very large confidence intervals and much missing data. In addition, of 14 patients who underwent end-of-therapy marrow biopsies, 13 showed no evidence of disease on pathological evaluation, demonstrating potent efficacy in clearing disease in the marrow. Ultimately, the durability of response will define the efficacy of the regimen, and with a median follow-up of 20.7 months, no patients have progressed or died (Figure 2B).

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

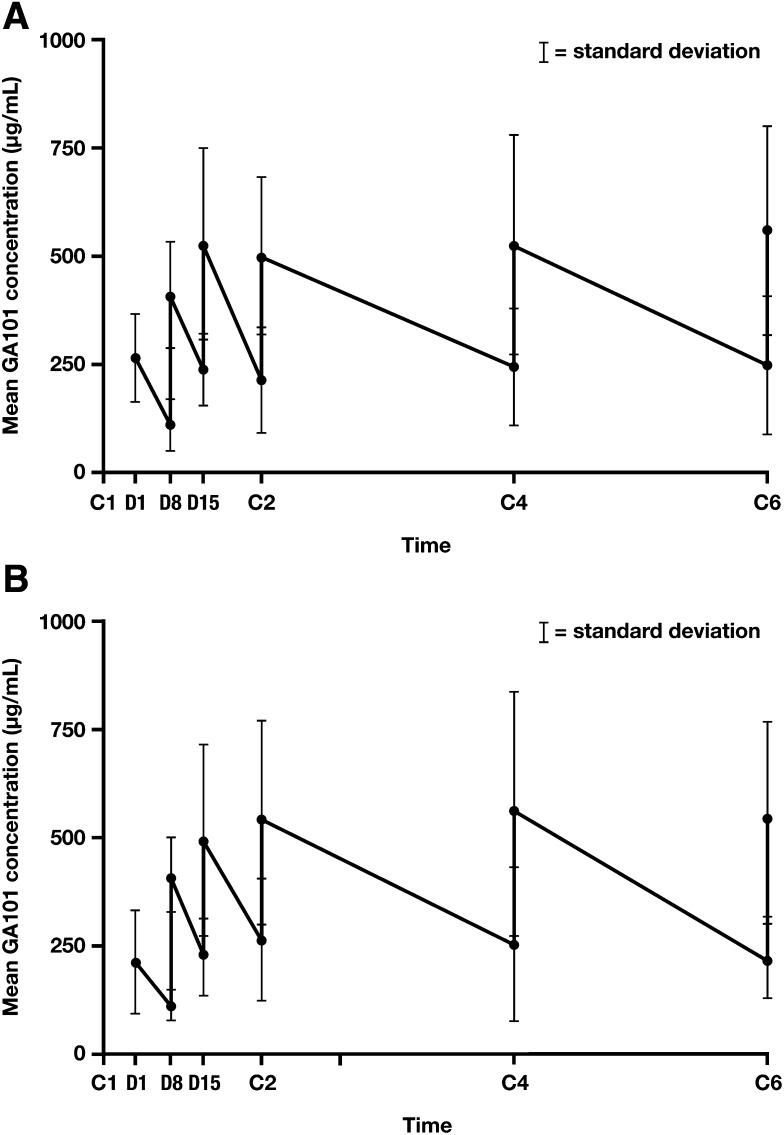

Thirty-eight patients (20 in the G-FC cohort and 18 in the G-B cohort) were evaluable for pharmacokinetics of obinutuzumab. No differences were seen between treatment arms, so data from both arms were pooled and compared with preexisting population PK models of obinutuzumab given as a single agent or in combination with chemotherapy to patients with CLL or other B-cell lymphomas (Figure 3A-B). The majority of values fell within the predicted range based on the model, suggesting that the addition of either FC or B did not alter the PK of obinutuzumab.

Figure 3.

Mean obinutuzumab serum concentrations in combination with chemotherapy. (A) Obinutuzumab plus B. (B) Obinutuzumab plus FC. C, cycle; D, day.

In the G-FC and G-B cohorts, baseline immunoglobulin A, immunoglobulin G, and immunoglobulin M values were similar, and median changes from baseline at the end of therapy were similar. Among patients with low immunoglobulin levels at the end of treatment, 3 of 16 patients (1 patient in the G-FC cohort and 2 patients in the G-B cohort), 2 of 11 patients (1 patient in each arm), and 2 of 17 patients (1 patient in each arm) recovered immunoglobulin A, immunoglobulin G, and immunoglobulin M levels, respectively, to within the normal range during the study follow-up. The median time to normalization had therefore not been reached for any immunoglobulin isotype level.

At the end of treatment, 36 of 41 patients with an assessment in the study had depletion of their B cells. With a median 22.1 months of follow-up, 11 patients (31%) had achieved B-cell recovery without evidence of disease progression. After the end of treatment, the median estimated time to B-cell recovery was 18.5 months (95% CI, 15.7-20.3 months) in the overall study population.

Discussion

Rituximab chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) combinations have been the mainstay of CLL therapy for fit patients, conferring an OS benefit. Given the recent data showing that CLL patients with comorbidities treated with obinutuzumab in combination with chlorambucil achieved higher ORR, CR rates, and longer PFS than patients treated with rituximab and chlorambucil,14 a study was warranted that examined the clinical activity of obinutuzumab with other chemotherapy agents commonly used with rituximab to treat fit patients with CLL. Here, we present phase 1b data from a parallel-cohort study showing that G-FC and G-B are well-tolerated and effective CIT regimens.

The toxicities seen on both arms of the study appear fairly similar to what one would expect for the cognate rituximab CIT regimen, with the caveat that this study was small and no formal statistical comparisons are possible. The median number of treatment cycles administered in both arms was similar to what has been previously reported in multicenter studies of both FC plus rituximab and B plus rituximab.2,4 The overall grade 3-4 neutropenia rate in the G-FC cohort does not appear greatly different (48%) from those reported for fludarabine and cyclophosphamide plus rituximab in CLL8 (34%)2 and CLL10 (89%),16 although more G-FC patients (62%) received myeloid growth factors for prophylaxis or treatment than CLL8 patients (19%). Infection rates in the G-FC cohort were similar to that reported in CLL8.2 In the G-B cohort the 55% incidence of grade 3-4 neutropenia (including 2 patients with febrile neutropenia) is higher than that previously reported with use of B and rituximab as initial therapy (20%).4 Several patients treated with either regimen had to discontinue therapy early after cycles 1 or 2, mostly due to cytopenias.

IRRs with obinutuzumab have been observed in earlier studies, including CLL11. In this study, IRRs were nearly universal on cycle 1 day 1, including grade 3-4 events in 20% of patients on this study. Fortunately all grade 3-4 events were confined to cycle 1 day 1. These events require careful patient management but can generally be managed well with potent corticosteroid prophylaxis and split dosing. At the American Society of Hematology’s annual meeting in 2014, Freeman et al presented an analysis showing that the first infusion of obinutuzumab is associated with a very rapid drop in circulating B-cell count accompanied by a sharp spike in multiple cytokines including interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosis factor α, suggesting that this cytokine release may relate to the frequency of IRRs.17 The ongoing GREEN trial also reported at the 2014 meeting by Bosch et al is exploring whether a smaller dose of 25 mg given at a slower rate (12.5 mg/h) on day 1 will reduce the incidence of IRRs.18

In this study, elevation of hepatic transaminases emerged as an associated finding particularly after early obinutuzumab infusions, but patients were asymptomatic and their laboratory abnormalities were self-limited, usually resolving within a week. Larger follow-up studies will be required to determine if hepatic transaminitis is more common with obinutuzumab in combination compared with single agent, or if it is more common in CIT regimens incorporating obinutuzumab relative to those incorporating rituximab.

Efficacy of the regimens was high in patients who continued on therapy and underwent full response evaluation. It is noteworthy that no patient on either arm of the study has had disease progression, now with median follow-up of 20.7 months on G-FC and 23.5 months on G-B. These results compare favorably with those of earlier studies, with the caveat that the current study had relatively small numbers of patients and a limited follow-up period. This efficacy is accurately reflected in the response rate data in the G-B cohort, in which most patients finished therapy and had a full response evaluation, allowing a 90% ORR and an impressive 45% CR/CRi rate. This contrasts with the response rate of patients treated with G-FC, whose ORR and CR rates are perhaps lower than expected, again with the caveat of small numbers. Nevertheless, the lack of disease progression in patients treated with G-FC, as well as the excellent CLL cell depletion and clearance of disease from the marrow, indicates that the G-FC regimen has substantial activity.

In summary, obinutuzumab in combination with chemotherapy has an acceptable safety profile when administered to previously untreated fit patients with CLL. IRRs were the most common AE; these most commonly occurred during the first infusion of obinutuzumab and were easily handled with corticosteroid premedication and split dosing. The adverse events observed in patients treated with G-FC or G-B, including myelotoxicity, were manageable. Our data demonstrate that obinutuzumab in combination with FC or B has promising activity when used in the therapy of patients with CLL.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families and the following investigators that participated in GALTON (GAO4779g): Paul Barr (James P. Wilmot Cancer Center, University of Rochester), Leonard T. Heffner (Winship Cancer Institute, Emory University), Robert Hermann (Northwest Georgia Oncology Centers, PC, William S. Gibbons Cancer Research Institute), Viran Holden (Mercy Medical Research Institute), Moacyr Ribeiro De Oliveira (Northwest Medical Specialties), and Javier Pinilla-Ibarz (H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center). They also thank the GALTON study management team (Roche/Genentech), Mijanur Rahman and Ross Farrugia for statistical programming support, Nicola Tyson for biostatistical support, and David Carlile and Michael Brewster for pharmacokinetic analysis support. The GALTON study was sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche. Editorial assistance was provided by Cheryl Wright at Gardiner-Caldwell Communications (Macclesfield, United Kingdom) and funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche.

Footnotes

Presented at the 55th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, New Orleans, LA, December 9, 2013.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: S.O., J.H., and T.J.K. designed the study; J.R.B., S.O., C.D.K., H.E., J.M.P., and T.J.K. enrolled patients; J.L. provided statistical analysis; J.R.B., J.L., J.H., and T.J.K. analyzed and interpreted data; J.R.B. wrote the first draft of the manuscript with assistance from J.H.; J.R.B., S.O., C.D.K., H.E., J.M.P., J.L., J.H., and T.J.K. reviewed and commented on the manuscript; and all authors had access to the primary study data and made a substantial contribution to the study, interpreted data, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.L. and J.H. are employees of Genentech. J.L., S.O., and T.J.K. receive research funding from F. Hoffmann-La Roche. J.L. and J.H. own stock in F. Hoffmann-La Roche. J.R.B. has served as a consultant for Genentech and F. Hoffmann-La Roche. T.J.K. has served as a consultant for, and received honoraria from, F. Hoffmann-La Roche. H.E. has served as a consultant for F. Hoffmann-La Roche and Genentech and has received honoraria from F. Hoffmann-La Roche. C.D.K. has received honoraria from Genentech. J.M.P. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jennifer R. Brown, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA, 02215; e-mail: jennifer_brown@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Byrd JC, Rai K, Peterson BL, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine may prolong progression-free survival and overall survival in patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an updated retrospective comparative analysis of CALGB 9712 and CALGB 9011. Blood. 2005;105(1):49–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. International Group of Investigators; German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Study Group. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1164–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keating MJ, O’Brien S, Albitar M, et al. Early results of a chemoimmunotherapy regimen of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as initial therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(18):4079–4088. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer K, Cramer P, Busch R, et al. Bendamustine in combination with rituximab for previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multicenter phase II trial of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(26):3209–3216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer K, Cramer P, Busch R, et al. Bendamustine combined with rituximab in patients with relapsed and/or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multicenter phase II trial of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(26):3559–3566. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.8061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knauf WU, Lissichkov T, Aldaoud A, et al. Phase III randomized study of bendamustine compared with chlorambucil in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26):4378–4384. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alduaij W, Ivanov A, Honeychurch J, et al. Novel type II anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (GA101) evokes homotypic adhesion and actin-dependent, lysosome-mediated cell death in B-cell malignancies. Blood. 2011;117(17):4519–4529. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-296913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mössner E, Brünker P, Moser S, et al. Increasing the efficacy of CD20 antibody therapy through the engineering of a new type II anti-CD20 antibody with enhanced direct and immune effector cell-mediated B-cell cytotoxicity. Blood. 2010;115(22):4393–4402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-225979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golay J, Da Roit F, Bologna L, et al. Glycoengineered CD20 antibody obinutuzumab activates neutrophils and mediates phagocytosis through CD16B more efficiently than rituximab. Blood. 2013;122(20):3482–3491. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-504043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patz M, Isaeva P, Forcob N, et al. Comparison of the in vitro effects of the anti-CD20 antibodies rituximab and GA101 on chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells. Br J Haematol. 2011;152(3):295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salles G, Morschhauser F, Lamy T, et al. Phase 1 study results of the type II glycoengineered humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody obinutuzumab (GA101) in B-cell lymphoma patients. Blood. 2012;119(22):5126–5132. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-404368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sehn LH, Assouline SE, Stewart DA, et al. A phase 1 study of obinutuzumab induction followed by 2 years of maintenance in patients with relapsed CD20-positive B-cell malignancies. Blood. 2012;119(22):5118–5125. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-408773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with GA101 plus chlorambucil in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and comorbidity: results of the CLL11 (BO21004) safety run-in. Leukemia. 2013;27(5):1172–1174. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(12):1101–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111(12):5446–5456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eichhorst B, Fink AM, Busch R, et al. Frontline chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine (F), cyclophosphamide (C), and rituximab (R) (FCR) shows superior efficacy in comparison to bendamustine (B) and rituximab (BR) in previously untreated and physically fit patients (pts) with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): final analysis of an international, randomized study of the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG) (CLL10 Study). Blood. 2014;124(21):19. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman CL, Morschhauser F, Sehn LH, et al. Pattern of cytokine release in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with obinutuzumab and possible relationship with development of infusion related reactions (IRR). Blood. 2014;124(21):4674. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosch F, Illmer T, Turgut M, et al. Preliminary safety results from the phase IIIb GREEN study of obinutuzumab (GA101) alone or in combination with chemotherapy for previously untreated or relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Blood. 2014;124(21):3345. [Google Scholar]