Abstract

It is unclear how the variability of kinematic errors experienced during motor training affects skill retention and motivation. We used force fields produced by a haptic robot to modulate the kinematic errors of 30 healthy adults during a period of practice in a virtual simulation of golf putting. On day 1, participants became relatively skilled at putting to a near and far target by first practicing without force fields. On day 2, they warmed up at the task without force fields, then practiced with force fields that either reduced or augmented their kinematic errors and were finally assessed without the force fields active. On day 3, they returned for a long-term assessment, again without force fields. A control group practiced without force fields. We quantified motor skill as the variability in impact velocity at which participants putted the ball. We quantified motivation using a self-reported, standardized scale. Only individuals who were initially less skilled benefited from training; for these people, practicing with reduced kinematic variability improved skill more than practicing in the control condition. This reduced kinematic variability also improved self-reports of competence and satisfaction. Practice with increased kinematic variability worsened these self-reports as well as enjoyment. These negative motivational effects persisted on day 3 in a way that was uncorrelated with actual skill. In summary, robotically reducing kinematic errors in a golf putting training session improved putting skill more for less skilled putters. Robotically increasing kinematic errors had no performance effect, but decreased motivation in a persistent way.

Keywords: motor learning, motivation, movement variability, motor skill, robotic training

the effective integration of robotic systems in motor skill training and neurorehabilitation requires an improved understanding of the learning mechanisms used by the human motor system when it interacts with these systems. These learning mechanisms involve both motor performance aspects and the psychological experience of the training; these two factors likely interact (Abe et al. 2011; Avila et al. 2012; Badami et al. 2011; Saemi et al. 2012; Trempe et al. 2012). Two prominent strategies for robotic-assisted training have emerged, both based on the manipulation of kinematic errors: error reduction (ER; also known as haptic guidance), and error augmentation (EA) (see review, Marchal-Crespo and Reinkensmeyer 2009). However, the conditions under which these strategies work best, and the learning and motivation mechanisms they stimulate, are at present unclear.

Haptic guidance reduces a person's kinematic errors during training to improve motor learning. Different forms of haptic guidance have been developed (Bluteau et al. 2008; Liu et. al. 2006; Lüttgen and Heuer 2012, 2013; Marchal-Crespo et al. 2013; van Asseldonk et al. 2009), but most of them share the goal of providing proprioceptive and/or visual cues that allow individuals to experience the ideal feel and look of a task. Experiments testing the efficacy of haptic guidance in improving motor performance have produced mixed results. Although there have been studies verifying that haptic guidance can improve the learning of both spatial and temporal motor tasks (Bluteau et al. 2008; Lüttgen and Heuer 2012; Marchal-Crespo et al. 2013; Marchal-Crespo and Reinkensmeyer 2008; Milot et al. 2010), other studies have shown that haptic guidance provides no significant benefits compared with either visual demonstration or unassisted training (Feygin et al. 2002; Liu et al. 2006; van Asseldonk et al. 2009; Winstein et al. 1994).

In contrast to ER strategies, EA training is based on the idea that motor learning is an error-driven process rather than a correct-feedback driven process. Thus increasing kinematic errors during the execution of a motor task should enhance the motor learning process by causing the motor system to respond more strongly or faster (Emken et al. 2007; Patton et al. 2006). Increased error could also enhance attentional mechanisms (Dvorkin et al. 2013), invoke adaptive impedance control mechanisms for reducing kinematic error (Franklin et al. 2007, 2013), or increase variability so that exploration of the task space and therefore learning is enhanced (Wu et al. 2014). Training with EA has been found to improve trajectory straightness in reaching (Cesqui et al. 2008), as well as the timing of a pinball task for more highly skilled trainees (Milot et al. 2010). One study that examined training of balance on a beam, however, found no benefits from EA training in improving short-term learning (Domingo and Ferris 2010).

Important but less well-studied aspects of robot-assisted motor training are the effect of the intervention on motivation. Stroke patients who received robot-assisted therapy using an ER strategy reported that such therapy was motivating (Housman et al. 2009), in part because of the improved self-efficacy accomplished with physical assistance (Reinkensmeyer and Housman 2007). Sport psychology studies have found that positive feedback increases participants' intrinsic motivation and feelings of self-efficacy for a given training program and can improve motor learning (Avila et al. 2012; Badami et al. 2011; Saemi et al. 2012). The experience of success can also improve consolidation in motor learning (Abe et al. 2011; Trempe et al. 2012).

For this study, we chose an engaging and well-known task–golf putting–to study the relative merits of a brief period of practice with ER and EA compared with normal practice. We were specifically interested in how these training strategies affected learning and motivation when trainees were already relatively well practiced at the task, i.e., after the initial familiarization/learning curve had plateaued. Training approaches that enhance motor learning in this stage would be useful because they are more relevant to real-world training. In this situation, we hypothesized that any benefits of ER training for learning “the feel” of the task would be minimal since the trainees had already acquired the feel of the task, limiting the effectiveness of ER training, while EA training would still be beneficial.

We also examined the role of ER and EA on the participants' perception of training using a self-reported motivation scale. We hypothesized that training with ER would increase feelings of competence and self-efficacy, but would lead trainees to feel less engaged and to perceive that they exerted less effort while training. Conversely, we hypothesized that training with EA would decrease feelings of competence and self-efficacy, but would lead trainees to feel more engaged and to perceive that they exerted more effort during training. We were especially interested if there would be persisting motivational effects of robotic error manipulation days after the practice with ER or EA had occurred. Portions of this work were reported previously in a conference paper (Duarte et al. 2013).

METHODS

Participants.

Thirty healthy participants (ages 20–30 yr; 8 women) with no history of neurologic disorders completed the experiment. One participant was left-hand dominant. Each participant provided written, informed consent in accordance with a protocol approved by the University of California at Irvine's Institutional Review Board.

Experimental apparatus and robot-generated dynamic environments.

Participants were instructed how to play a game of virtual golf using a 3 degrees-of-freedom lightweight haptic robot (PHANToM 3.0 Premium, Sensable Technologies). The robot handle attached to the robot arm through a passive 3 degrees-of-freedom gimbals (Fig. 1A). To play the game, seated participants controlled the head of a virtual golf club using their dominant hand to putt a virtual ball to either a near or far target. The haptic robot was used to record the position, velocity, and forces and to apply the prescribed forces during game play at 1,000 Hz.

Fig. 1.

A: experimental setup for a participant playing the virtual putting game. Participants controlled the head of a virtual putter by using a 3 degrees-of-freedom haptic robot. The computer screen provided participants with visual feedback about their performance, which included a scoring system and a streak counter. B: two sample trajectories, one for the short target and one for the long target, in the velocity vs. position (state-space) domain. The subcomponents of the swing are labeled as follows: backswing, downswing, and follow through. The arrows around the long target represent the error reduction (ER) force field, while the arrows around the short target represent the error augmentation (EA) force field. Note that the force fields were only active during the downswing. [Photograph reprinted with permission.]

To decrease variability in putting style, motion of the robot was constrained, via software, to one dimension, a straight line in the x-axis parallel to the participant's shoulders just above waist height. The use of a virtual environment allowed us to also remove the variability due to the putting surface (a constant friction force was the only force acting on the virtual ball after impact), the quality of the impact (we assumed no energy loss during impact), and the angle of impact (the impact angle was always in a straight line to the hole). In this controlled environment, impact velocity alone determined the distance traveled by the ball. Speed control is an important parameter in many sporting activities, but one which, to our knowledge, has only been studied in one experiment in the context of robotic training (Marchal-Crespo et al. 2013).

We divided the swing of the putt into three parts: backswing, downswing, and follow through (Fig. 1B) and defined the impact velocity as the velocity at which the virtual club crossed the starting position (i.e., at the end of the downswing). A small and constant amplitude impulse, opposite to the direction of motion, was applied at impact to simulate the impact with the ball. The force fields used for EA and ER were active only during the downswing portion of the putt. Specifically, the robot was programmed to provide a dynamic environment in which participants' velocity errors were haptically reduced (ER), augmented (EA), or unaltered (control). In ER training mode, the robot decreased velocity errors proportional to the predicted error for each putt. In the EA training mode, the robot increased velocity errors proportional to the predicted error. In the control condition, the robot did not manipulate velocity errors.

The force fields for the ER and EA training conditions were defined as:

where ẋerror is velocity errors, and the gains, BER and BEA, were set higher for the near target (ER: 0.0035 kg·m−1·s−1; EA: −0.0016 kg·m−1·s−1) than the far target (ER: 0.003 kg·m−1·s−1; EA: −0.0015 kg·m−1·s−1) because the impact velocities required to perform the task were lower for the near target (putting to the center of the hole required an impact velocity of 1.12 m/s and 1.65 m/s for the near and far targets, respectively). The gains were kept constant across all participants. These gains were chosen after extensive pilot testing to find force fields that significantly decreased impact velocity errors while being qualitatively unnoticeable to participants, because we wanted to produce an environment in which the participant attributed errors to their own performance and not the robot (Kluzik et al. 2008).

We used the phase space representation of the swing to compute the velocity errors (Fig. 1B) during the downswing. The velocity error was defined as the difference between a target trajectory and the participant's downswing trajectory. To compute the target trajectory for a given swing, we created an algorithm whose effect was to define a trajectory that began at the onset of the downswing (immediately after the end of the backswing), at which point the head velocity was zero, and ended at the location of the virtual ball with the velocity equaling the desired impact velocity. This desired impact velocity was the velocity that would cause the ball to travel from its initial position to the center of the target.

The target trajectory was obtained as follows. First, we defined an ideal trajectory for the near and far targets by averaging hundreds of successful putts performed during pilot testing. We then stored these ideal trajectories in a look-up table as xideal, ẋideal pairs. Finally, we defined a morphing factor, m, that decreased linearly from a value of 1 at the start of the downswing to a value of 0 at the end of the downswing (i.e., the location of ball impact). The target trajectory was then calculated using the following algorithm at the moment the putter reached its maximum backswing length xbsMax:

where xbsIdeal is the location of the putter head at the start of the ideal downswing trajectory, which is the first entry in the look-up table.

We created a scoring mechanism to further engage participants in the experiment. Participants were shown, on the same screen as the game (see Fig. 1A), the error of the last putt (defined as the percentage error from the ideal impact velocity), the mean error of the last 5 putts, and the mean error of all putts completed. They also saw their current streak counter, defined as the number of consecutive putts that were within a 10% error from the center of the hole (i.e., “sunk putts”), as well as the maximum streak they had achieved during that session. A “sunk putt” was also rewarded by playing the sound of a golf ball dropping inside of the hole.

Experimental protocol.

Prior to starting the experiment, participants were instructed verbally and by demonstration how to perform the desired putting motion. The putting motion required an initial shoulder abduction (backswing), followed by shoulder adduction across the body (downswing and follow through) while keeping the wrist straight and elbow bent (Fig. 1A). Participants were also told that the objective of the game was to impact the ball so that it would reach the center of the target shown on the screen.

A trial started once a participant addressed the ball by placing the virtual club over a rectangular target displayed behind the pending location of the ball and held the club at this position for 1 s. A virtual golf ball then appeared directly in front of the club, and the participant was allowed to putt the ball. Participants were also shown a line across the path of their backswing that marked the minimum distance for the backswing (a point that experienced participants always passed when practicing). We displayed this line to prevent participants from putting using undesired motions such as a very short backswing followed by a jerky, forced, downward motion dissimilar to skilled putting motion. To prevent this aberrant style of putting, and the possibility of a switch in style during the experiment, we programmed the ball so that it would not move at impact unless the backswing passed the minimum length criterion.

The participants practiced putting on three separate days (Fig. 2). On day 1, the initial practice day, they performed a total of 100 putts, 50 to each target location, with no force fields applied. The target locations were randomized prior to the experiment, and all participants were presented with the same randomized order of target locations. The purpose of the initial practice day was twofold: 1) familiarize participants with the task, removing any learning effects due to the initial interaction with the robot and experience of the task (i.e., we wanted participants to be relatively competent at the task prior to exposure to the force fields), and 2) extract an initial putting skill measure that was then used to divide participants into training groups with matched average initial skill. Skill matching was achieved by ranking the 30 participants based on their average mean squared error of impact velocity during the second half of the session on day 1, taking sequential blocks of three participants from this ranking list, and randomizing each block of three participants into the three training conditions.

Fig. 2.

Experimental protocol. The experiment was carried out on 3 separate days for each participant. On day 1, all participants trained without force fields for 100 putts to become familiar with the task and have their skill level assessed. On day 2, which occurred at least 1 wk after day 1, participants putted 40 trials without haptic input to warm-up and measure pretraining skill, 90 trials with force fields (depending on their group), and 40 trials without force fields to measure short-term skill retention. Finally, on day 3, all participants putted 100 trials without force fields to measure their long-term skill retention. Throughout all days of practice, participants were periodically forced to take breaks of at least 1 min during which they responded to four questions (4Q) concerning motivation during practice; they also answered a set of 13 motivation-related questions (13Q) at the end of each day.

Day 2 was performed 1 wk after day 1, and it was on this day that the participants trained with the ER or EA force fields, or in the control condition (Fig. 2). A total of 170 putts were divided into three phases: 1) a baseline warm-up/assessment phase without force fields (40 trials); 2) a training phase with the force fields (90 trials); and 3) a short-term retention assessment without force fields (40 trials). The participants were unaware of this breakdown. The target location was randomized for the baseline and short-term retention phases with 20 trials to each target. It was in the force-field training phase on day 2, and only during this phase, that some subjects experienced ER or EA force fields, depending on their group. For this phase, the same target location was presented in sets of three consecutive trials. The goal was to resemble a training session in which a trainee adjusts his or her execution across several attempts based on previous errors at the same target. This pattern of three putts to the same distance was repeated 15 times for the near target, and 15 times for the far target, with target distance randomly mixed, resulting in 45 trials to each target, or, a total of 90 practice putts with the force field on. On day 3, which occurred 1 to 3 days after day 2, long-term retention was evaluated by asking participants to repeat the same 100 trials as on day 1 without any robotic force fields.

Rest breaks of at least 1 min were periodically scheduled during all sessions to minimize fatigue. The schedule of breaks was as follows (Fig. 2): days 1 and 3, trials 33 and 66, and day 2, trials 30, 60, 90, 120, 150. Note that the breaks on day 2 were scheduled at least 10 trials before or after changing the force fields so that they did not interfere with the transitions from putting with or without the force fields.

Assessment of motivation.

At the end of each day of the experiment, participants responded to 13 questions selected from the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI), a reliable and valid scale (Ryan 1982), (Table 1). During the periodic rest breaks, the participants also responded to a subset of four questions (marked with a asterisk in Table 1). Note that the first break on day 2 was scheduled before the force fields were applied; this provided a baseline measurement of the responses that was then used to compare the changes in responses due to practice with the force fields.

Table 1.

IMI questionnaire

| Question No. | Question Statement |

|---|---|

| 1 | I enjoyed doing this activity very much |

| 2 | I felt very tense while doing this activity |

| 3 | I would describe this activity as very interesting |

| 4 | This activity did not hold my attention at all* |

| 5 | I was anxious while working on this task |

| 6 | After working at this task for a while, I felt pretty competent* |

| 7 | I put a lot of effort into this* |

| 8 | I think that doing this activity was very useful |

| 9 | I am satisfied with my performance at this task* |

| 10 | This activity was fun to do |

| 11 | I think this is an important activity |

| 12 | I tried very hard on this activity |

| 13 | I thought this activity was quite enjoyable |

Set of questions from the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) used to assess motivation, competence, and effort. Questions marked with an asterisk are part of the subset of questions given at each break on day 2. Participants responded using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree).

Data analysis.

We defined motor skill as the variability in the impact velocity of the putt. Previous studies have shown that the main differentiator between highly skilled and lowly skilled putters lies in the variability in their impact velocity; this is in spite of their average impact velocities being comparable (Lee et al. 2008). To calculate variability, we first removed trials where the impact velocity was three standard deviations away from the mean for each participant at each experimental phase of the experiment. Variability was then calculated as the standard deviation of the sequence of impact velocities achieved at a target location (near or far) during a given experimental phase (pretraining assessment, short-term assessment, and long-term assessment; see Fig. 2 for the trial numbers corresponding to these phases). We performed initial postprocessing of the data using Matlab (Mathworks, version 7.8); we used the R-package (version 3.0.1) to perform the linear mixed-model analysis described below.

We used a linear mixed-model (Eq. 1) to measure the effects that the two target locations (near vs. far; fixed effect), the three training conditions (control, error-reduction, error-amplification; fixed effect), the two assessment sessions (short- and long-term; fixed effect), and the pretraining skill level (modeled as a covariate; fixed effect) had on the change in variability (response variable) measured from the pretraining assessment on day 2 to the short-term retention assessment (end of day 2) and to the long-term retention assessment (day 3). We modeled the subjects as random effects. We defined the change in variability as the percent change in variability between each retention assessment and the pretraining assessment. In this model, we used the control group as the reference for analyzing the change in variability for both the ER and EA conditions. We included interaction terms between training condition and initial skill level, target location, and retention assessment in the model. Following an initial fit of the model, we performed a model comparison analysis using the Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion criteria to determine which factors (both main and interactions) were relevant in the model. Using this approach, we reached a model that included the main effects of pretraining skill level, training condition, and target location, and the interaction terms between training condition and pretraining skill level (Eq. 1). Following the fit of the model, the distribution of the residuals was visually inspected for normality using Q-Q plots.

| (1) |

We analyzed differences in variability between groups at the pretraining assessment using a one-way ANOVA. We analyzed the effect of turning on the force field within a group using a paired t-test of change in variability calculated between the end of the pretraining assessment on day 2 (last 10 trials of the pretraining assessment) and the start of the force-field training on day 2 (first 10 trials of force-field training). We analyzed offline learning between groups using a one-way ANOVA (with group as the main factor) of change in variability, calculated between the end of the short-term assessment (last 10 trials of the short-term retention assessment; end of day 2) and the start of the long-term assessment (first 10 trials of the long-term retention assessment; start of day 3). For this ANOVA, we used only the last 10 trials in the short-term assessment phase because we wanted to ensure that any short-term effects of training with the force fields had washed out (i.e., after-effects). We used only the first 10 trials in the long-term assessment phase, because we were interested in performance at the start of the day and did not want further performance improvements that could accrue with the 100 more trials of practice in this phase to bias the measure of offline learning. If an ANOVA was significant, multiple comparisons were carried out using Tukey's range test.

To measure the effects of force field training on motivation, we compared the responses to the 13 IMI questions at the end of day 2 and day 3 of the experiment relative to the responses given at the end of day 1. We also analyzed the effect of force-field training on motivation at a finer time resolution during each session using the subset of four questions of the IMI given during the rest breaks. For this within-day analysis, we used the response at break 1 as the reference point. We compared the changes in responses at each day, or break, using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA with training condition as the main factor. Tukey's range test was used on pairwise comparisons, if the ANOVA was significant.

For all tests, significance was set at a P value below α = 0.05; P values below 0.1 are also reported.

RESULTS

Did the force fields modulate kinematic variability?

After day 1, participants were relatively well practiced at the task. All groups had comparable performance at the end of the pretraining assessment on day 2 for both the near and far target locations [near target: ANOVA, F(2,27) = 0.16, P = 0.86; far target: ANOVA, F(2,27) = 1.69, P = 0.20]. Once the force fields were turned on (during the force-field training phase on day 2), the EA force field significantly increased participants' impact velocity variability at both target locations (Fig. 3; near target: 105.50 ± 24.29%; far target: 101.27 ± 26.01% SE; paired-sample t-test, near target P = 0.002; far target P = 0.004), while the ER field decreased (near target: −56.22% ± 5.80 SE; far target: −41.68% ± 9.37 SE), the impact velocity variability for both target locations (Fig. 3; paired-sample t-test, near target P < 0.001; far target P = 0.002); thus the force fields modulated kinematic errors during the training session as planned.

Fig. 3.

Effect of the force fields on kinematic variability. A: near target. B: far target. The ER force field significantly reduced (near target: −56.22 ± 5.80% SEM; far target: −41.68 ± 9.37% SEM) the kinematic variability of participants (paired-sample t-test, near target P < 0.001; far target P = 0.002). The EA force significantly increased (near target: 107.50 ± 24.29% SEM; far target: 101.27 ± 26.01% SEM) the kinematic variability of participants (paired-sample t-test, near target P = 0.002; far target P = 0.004). Stars denote significant differences. CTRL, control.

Did experiencing the force fields affect skill retention?

There was no main effect of training with the force fields on the change in variability at the short- or long-term retention assessment relative to the control condition [Table 2 and Fig. 4; training condition main effect: ER, β = −35.02, t(27) = −1.82, P = 0.08; EA, β = −20.53, t(27) = −1.20, P = 0.24]. The pretraining skill level was a strong regressor on the change in variability at both retention assessments [Table 2 and Fig. 4; initial skill level main effect: β = 412.23, t(84) = −4.12, P < 0.001], meaning that participants who were initially less skilled at the task retained more skill improvement after either force-field or control training. There was a significant interaction effect between pretraining skill level and the training condition for the ER group [Table 2 and Fig. 4; pretraining skill and ER interaction: β = 246.45, t(84) = 1.97, P = 0.05], but not for the EA group [Table 2 and Fig. 4; pretraining skill and EA interaction: β = 137.25, t(84) = 1.15, P = 0.25]. That is, initially less skilled participants benefited significantly more from the exposure to ER relative to the control group, which always trained without a force field.

Table 2.

Results of the linear mixed-effects model of change in impact velocity variability

| Estimate | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial skill level | 412.23* | 86.90 | 244.62, 579.84 |

| Far target | −17.45* | 4.40 | −25.93, −8.96 |

| ER | −35.02 | 19.28 | −73.39, 3.35 |

| EA | −20.53 | 17.10 | −54.55, 13.50 |

| Initial skill level × ER | 246.45* | 125.10 | 5.17, 487.72 |

| Initial skill level × EA | 137.25 | 118.53 | −91.36, 365.86 |

ER, error reduction; EA, error augmentation; SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval. Results from the linear mixed-model revealed that the initial skill level had a significant effect on the change in kinematic variability across all participants, with those participants who were initially less-skilled benefiting the most [β = 412.23, t(84) = −4.12, P < 0.001]. For these participants, those whose kinematic variability was reduced (i.e., ER group) had a significant improvement over those in the control condition [β = 246.45, t(84) = 1.97, P = 0.05].

P ≤ 0.05.

Fig. 4.

Linear mixed model to analyze motor skill retention. A linear mixed model with three training conditions, two target locations, two retention assessments, and the participants' pretraining skill level was used to measure the retention of motor skill (impact velocity variability in putting) after training with the ER and EA force fields. In this figure, positive changes reflect improvements in motor skill. The pretraining skill level was a significant regressor [β = 412.23, t(84) = −4.12, P < 0.001]; therefore, participants who were initially less skilled at the task benefited more from the training. An interaction between the pretraining skill level and the ER group [β = 246.45, t(84) = 1.97, P = 0.05] revealed that, relative to the CTRL group, initially less-skilled participants benefited more from training with reduced kinematic variability.

The change in variability was significantly lower for the far target relative to the near target [target location main effect: β = −17.45, t(84) = −3.96, P < 0.001]. This is indicative of the greater difficulty of putting to a longer distance.

Kinematic error manipulation and offline learning.

We quantified offline learning as the change in performance from the end of day 2 (last 10 trials of the short-term retention assessment) to the beginning of day 3 (first 10 trials of the long-term retention assessment). Offline learning, or lack thereof, was significantly different between groups [Fig. 5; ANOVA, F(2,27), P = 0.03] for the far target but not the near target. On average, only participants in the ER training group showed offline learning at the far target. Follow-up multiple comparisons revealed significant differences in offline learning between the ER and EA groups (Tukey test, P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Offline learning across training groups. We defined offline learning as the change in performance from the end of day 2 to the start of day 3. A: no significant differences in offline learning were found for the short target. B: there was a significant difference in offline learning between training groups for the long target (ANOVA P = 0.03, follow-up Tukey test indicated pairwise difference between ER and EA, P < 0.05). Star denotes significant difference. Error bars represent the standard error.

Error-based learning and putt distance recalibration.

During the force-field training phase, participants were allowed to putt three times in a row to each target. We expected an improvement in performance during the sequence of three putts as a result of trial-to-trial, error-based learning. Participants in the EA group significantly reduced errors from the first putt to the second and third putts for the near putt [Fig. 6A; ANOVA, F(2,42), P < 0.001]. For the control group at the far target, participants' significantly reduced errors by the third putt [Fig. 6B; ANOVA, F(2,42), P = 0.037].

Fig. 6.

Error-based learning and recalibration errors. A and B: signed errors incurred during the training phase of the experiment. A: near target. B: far target. For error-based learning, we expected errors to decrease for consecutive putts to the same target location. This was evident in the EA group at the short target (ANOVA, P < 0.001; A) and in the CTRL group at the long target (ANOVA, P = 0.037; B). In A and B, the stars indicate significant differences in the error size for a training condition. C and D: signed recalibration error (i.e., the error incurred after there is a change in target location) for the short (C) and long (D) target locations. We found a clear trend for the recalibration error to be in the direction of the previous putt. Participants had a tendency to overshoot the short target and undershoot the long target following a change in the target location. In C and D, the asterisks show significant differences between experimental phases for a given training condition; the stars show significant differences between training conditions for a given experimental phase. Error bars represent the standard error.

When participants switched from practicing at the near target to practicing at the far target, they exhibited a systematic error toward the distance of the previous putt. That is, participants on average overshot the near target and undershot the far target following a change in target location. We term this recalibration error (Fig. 6, C and D). While the force fields were being applied, EA increased recalibration error, while ER reduced it at the near target. When the force fields were removed, the group that trained with EA had significantly reduced calibration error relative to the other two groups at the near target. This effect of practicing in the EA force field was reversed at the far target, with EA causing a larger recalibration error at short- and long-term retention.

How did modulating kinematic variability affect the subjective experience of training?

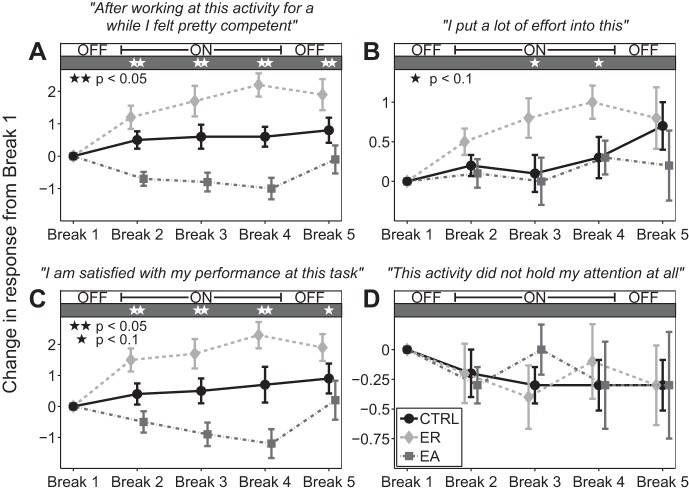

Manipulating kinematic errors on day 2 had a significant effect on how participants experienced the task on both days 2 and 3 (Figs. 7 and 8). At the first break after experiencing the force field on day 2, participants in the ER group reported higher feelings of competence, while participants in the EA group reported lower levels [Table 1, question 6 (Q6); Fig. 7A; Kruskal-Wallis test, breaks 2–5: P < 0.05]. Participants in the ER group had a tendency to report higher effort levels (Table 1, Q7) while the error-reducing force field was active; however, this difference failed to reach significance at the 95% confidence level (Fig. 7B; Kruskal-Wallis test, break 3: P = 0.08; break 4: P = 0.06). Participants in the ER group reported higher levels of satisfaction (Table 1, Q9), while those in the EA group reported lower levels (Fig. 7C; Kruskal-Wallis test, breaks 2–4: P < 0.05 and break 5: P = 0.07). Finally, experiencing the force fields did not have a significant effect on the reported levels of attention to the task between training conditions (Table 1, Q10, Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Responses to the subset of 4Q from the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) during training on day 2. The top bar, labeled with ON, indicates when the force field was active (i.e., during breaks 2, 3, and 4). Stars denote significant differences by Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA. Participants in the ER group reported high levels of competence (A) and satisfaction (C), while the EA group reported the opposite. B: the ER group also reported higher effort. D: no differences were found in the reported levels of attention. Error bars represent the standard error.

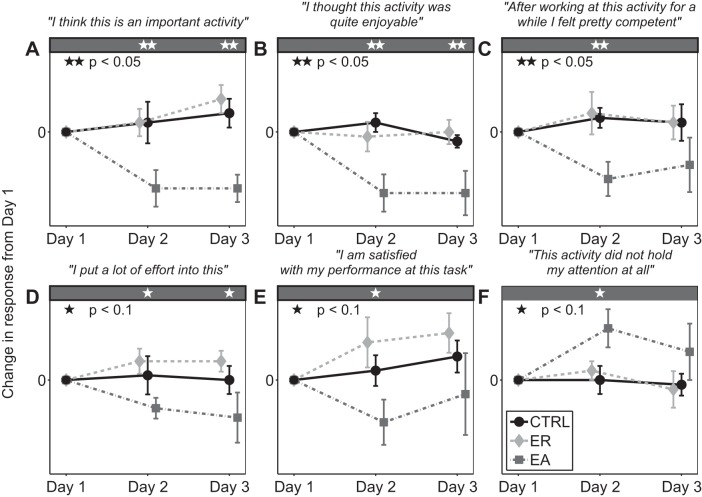

Fig. 8.

A–F: responses to the subset of 13Q from the IMI given at the end of each day. Only those questions with significant or near significant differences between training groups are shown. There was a significant trend for participants in the EA group to report more negative feelings toward the training at the end of day 2 (A, B, C, and E). Some of these feelings persisted at the end of day 3 (A and B), even though the force field was not active during day 3. In addition, the EA group showed a tendency to report a lower level of effort put into the task on days 2 and 3. Error bars represent the standard error. Stars denote significant difference.

On day 3 (Fig. 8), participants in the EA group continued to report more negative feelings toward the task. Regarding the importance of the task, (Table 1, Q11), the EA group reported significantly lower scores both at the end of day 2 (Fig. 8A, Kruskal-Wallis test, P = 0.02), and day 3, 1–3 days and 140 putts after having experienced the force fields (Fig. 8A, Kruskal-Wallis test, P = 0.001). This same behavior was seen in relation to the reported levels of enjoyment of the task (Table 1, Q13; Fig. 8B; Kruskal-Wallis test, day 2: P = 0.003; day 3: P = 0.02). EA caused participants to report lower feelings of competence and satisfaction on day 3 and reduced effort and attention, but these trends did not reach statistical significance (Table 1, Q7, 9, 4; Fig. 8, D–F). Responses to the other 7 questions were not significantly different between training conditions.

The participants expressed these subjective motivational differences across groups, despite the fact that their absolute skill levels were comparable at the end of day 3 [ANOVA, F(2,27) = 0.82, P = 0.45]. There was no correlation between the participants' putting skill at the end of day 3 and the subjective reports of importance of the task (IMI, Q11) or enjoyment of the task (IMI, Q1).

DISCUSSION

We assessed the effects of robotically modulating kinematic errors during a short period of practice on motor skill learning and motivation for a virtual game of golf putting for participants who were well-practiced at the task. We manipulated velocity errors by reducing them (ER force field), amplifying them (EA force field), or leaving them unchanged (control condition). We found that, across all training conditions, those participants who were initially less skilled benefited from training. For these participants, training with reduced kinematic variability led to increased benefits in the reduction of impact velocity variability. Training with the ER force field also led to higher feelings of competence and satisfaction, while training with the EA force field caused participants to feel less competent and less satisfied. We were surprised that this latter effect persisted even days after participants had experienced the EA force field. We will now relate these results to previous work in motor learning to outline the conditions under which modulating kinematic variability may be useful for motor skill training.

When is reducing kinematic variability during training beneficial?

The benefits of reducing kinematic errors (i.e., haptic guidance) during training have been reported previously for learning to drive a wheelchair (Marchal-Crespo and Reinkensmeyer 2008), making spatiotemporal trajectories (Feygin et al. 2002; Lüttgen and Heuer 2012), and in simulated tennis (Marchal-Crespo et al. 2013). For these tasks, it was suggested that ER aids in the development of the sense of timing for the task by giving haptic cues. The putting task reported in this experiment was a velocity-control task where participants had to achieve a target velocity of the hand at the impact location. This can be viewed as a type of timing task, in that participants had to learn to control the timing of the downswing. Thus this work supports and extends the observation that ER training may be useful for teaching timing-related movement features via haptic cues.

The benefit of ER was stronger for less skilled participants. This result agrees with previous findings in a simulated tennis environment (Marchal-Crepo et al. 2013) and for a steering task (Marchal-Crespo et al. 2010). Note that, in contrast to these previous experiments, we designed the experiment with an initial practice day to ensure subjects were relatively well practiced at the task. In this case, ER still benefitted the less skilled subjects. This is still consistent with a framework in which the benefits of ER are strongest when the basic feel of the task has not yet been learned well.

The short period of training with ER caused higher feelings of competence and satisfaction, and a trend toward higher self-reported effort levels. Thus ER may be useful for boosting the willingness to engage in training, at least during a single training session. The observation that training with ER improved offline learning for the far target may also be attributable to the motivational effects we observed. Previous studies have found that providing positive feedback during training promotes retention (Abe et al. 2011; Saemi et al. 2012). For example, participants who experienced higher success rates in a visuomotor rotation adaptation test during training, by virtue of relaxing the criterion for counting a successful trial, performed better at a 24-h retention test than participants who experienced less success by virtue of a stricter success criterion (Trempe et al. 2012). A possible mechanism that could account for better learning with more experience of success is error-related negativity, which is the reduced release of dopamine during motor learning when failure is common (Robertson and Cohen, 2006). ER prevents performance failure and thus may in some training situations cause a greater release of dopamine, better sealing motor memory (Abe et al. 2011; Trempe et al. 2012).

Effects of augmenting kinematic variability during training.

Training with EA has been found to be beneficial in tasks that involve position control (Abdollahi et al. 2014; Emken and Reinkensmeyer 2005; Huang et al. 2010; Patton et al. 2006;). Error augmentation was also found to be helpful for more skilled subjects who learned a pinball-like timing task (Milot et al. 2010). In addition, previous studies have correlated increased variability during training with enhanced motor learning (Hidler et al. 2009; Shah et al. 2012; Wu et al. 2014). We failed to extend these findings to the velocity control task studied here.

Why was EA not beneficial? We anticipated EA would improve at least short-term learning through three mechanisms: 1) increasing attention to the task; 2) enhancing error-based learning; or 3) impedance control. Regarding the first mechanism, self-reports of attention were not different during training for the three groups. This may be a result of our designing the EA field to be subtle enough that participant's attributed performance changes to themselves rather than the robot. However, although it did not produce an overall benefit to impact velocity variability, the EA group did reduce their recalibration error more for the near target at short-term retention, which might indeed be due to increased attention to this type of error.

With regards to enhancing error-based learning, participants in the EA group indeed showed evidence of error-based learning, but only clearly at the near target location, as they decreased their error from the first putt to the second and third putts in each set of three putts for the near target. This repeated exercising of error-based learning mechanisms during the force field exposure, however, did not produce a detectable benefit at the short- or long-term retention assessments. This may be because error-based learning is useful only for larger systematic errors, and not for reducing more subtle variance in movement execution.

Regarding the possibility of impedance control, we did not see a gradual decrease in variability across the practice period when the EA force field was active, as might have been expected if the motor system was iteratively increasing impedance (Franklin et al. 2007). This could have been because the EA field was relatively subtle, or because it is difficult to increase impedance about a target velocity. The mechanisms of the beneficial effects of EA need further research; a useful future direction would be to measure mechanical impedance during the putting task.

Participants who trained with EA reported lower levels of competence and enjoyment during training, and, surprisingly, on day 3, when the force fields were inactive and their performance was as comparable to the control group, they continued these reports. Evidently the experience of an inexplicable increase in error and corresponding decline in success in sinking putts persistently impaired motivation in a way that was out-of-step with actual performance. Two factors that have been shown to correlate with motivation in exercise training are as follows: 1) perception of success, which refers to how successful trainees feel they were in improving their ability through training; and 2) self-efficacy, which refers to how confident a trainee is that they could achieve a target performance level if tested again (McAuley and Duncan 1989; McAuley et al. 1991). The increase in kinematic variability almost certainly had a negative effect on perception of success because trainees experienced a long period of time in which they rarely sank putts. The fact that EA suddenly and inexplicably caused trainees' errors to become large, and that trainees were not able to adapt to the EA field while it was on, likely also diminished self-efficacy. This is a significant caveat that should be considered when applying EA training in the real world.

Implications for robot-assisted motor skill training and neurorehabiliation.

Self-efficacy is an important concept in exercise, sports and neurorehabilitation training because it can lead to higher motivation and persistence when faced with difficulties in performing the task (Bandura 1977). Theories of self-efficacy argue that a person's “expectations of personal mastery affect both initiation and persistence of coping behavior” (Bandura 1977). A possible approach for robotic-assisted training is to use ER force fields early on in motor training to generate an expectation of behavior that leads trainees to a greater willingness to practice. In this scenario, people's capabilities are reinforced during training by using devices that provide assistance, such as ER training, to improve motivation and perceived self-efficacy. An important issue is whether negative motivation and self-efficacy effects could occur when the subject leaves the laboratory and has difficulty performing tasks. Performing without robotic assistance in the real world may act like an EA condition. Key questions are how much the motivational effects generalize to other tasks encountered in the real world, and what is the effect on motivation of the interplay between laboratory success and real-world struggle.

For neurorehabilitation, similar motivational and motor learning mechanisms are likely operating. Subjective reports from stroke patients who have undergone robotic therapy suggest they find it more motivating in part because it allows them to accomplish tasks they normally could not achieve (Reinkensmeyer and Housman 2007). There is evidence for a threshold-based dynamic in achieved rehabilitation dosage after stroke where patients who achieve a threshold level of movement ability engage in spontaneous use of the hand outside of therapy, further increasing the dose of therapy and improving their outcomes (Schweighofer et al. 2009). The evidence presented in this paper for the ability of ER to improve a participant's perception of training provides a possible explanation as to why robot-assisted rehabilitation therapies sometimes have shown increased retention levels compared with conventional training (Housman et al. 2009; Lo et al. 2010).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.E.D. and D.J.R. conception and design of research; J.E.D. performed experiments; J.E.D. and D.J.R. analyzed data; J.E.D. and D.J.R. interpreted results of experiments; J.E.D. prepared figures; J.E.D. and D.J.R. drafted manuscript; J.E.D. and D.J.R. edited and revised manuscript; J.E.D. and D.J.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Justin B. Rowe for insights in the design of the experiment.

REFERENCES

- Abdollahi F, Case Lazarro ED, Listenberger M, Kenyon RV, Kovic M, Bogey RA, Hedeker D, Jovanovic BD, Patton JL. Error augmentation enhancing arm recovery in individuals with chronic stroke: a randomized crossover design. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 28: 120–128, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe M, Schambra H, Wassermann EM, Luckenbaugh D, Schweighofer N, Cohen LG. Reward improves long-term retention of a motor memory through induction of offline memory gains. Curr Biol 21: 557–562, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila LTG, Chiviacowsky S, Wulf G, Lewthwaite R. Positive social-comparative feedback enhances motor learning in children. Psychol Sport Exerc 13: 849–853, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Badami R, VaezMousavi M, Wulf G, Namazizadeh M. Feedback after good versus poor trials affects intrinsic motivation. Res Q Exerc Sport 82: 360–364, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 84: 191–215, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluteau J, Coquillart S, Payan Y, Gentaz E. Haptic guidance improves the visuo-manual tracking of trajectories. PLos One 3: e1775, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesqui B, Macrì G, Dario P, Micera S. Characterization of age-related modifications of upper limb motor control strategies in a new dynamic environment. J Neuroeng Rehabil 5: 31, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo A, Ferris DP. The effects of error augmentation on learning to walk on a narrow balance beam. Exp Brain Res 206: 359–370, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte JE, Gebrekristos B, Perez S, Rowe JB, Sharp K, Reinkensmeyer DJ. Effort, performance, and motivation: Insights from robot-assisted training of human golf putting and rat grip strength. IEEE Int Conf Rehabil Robot 2013: 6650461, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorkin AY, Ramaiya M, Larson EB, Zollman FS, Hsu N, Pacini S, Shah A, Patton JL. A “virtually minimal” visuo-haptic training of attention in severe traumatic brain injury. J Neuroeng Rehabil 10: 92, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emken JL, Benitez R, Sideris A, Bobrow JE, Reinkensmeyer DJ. Motor adaptation as a greedy optimization of error and effort. J Neurophysiol 97: 3997–4006, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emken JL, Reinkensmeyer DJ. Robot-enhanced motor learning: accelerating internal model formation during locomotion by transient dynamic amplification. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 13: 33–39, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feygin D, Keehner M, Tendick F. Haptic guidance: experimental evaluation of a haptic training method for a perceptual motor skill. IEEE Haptics Symp 2002: 40–47, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin DW, Liaw G, Milner TE, Osu R, Burdet E, Kawato M. Endpoint stiffness of the arm is directionally tuned to instability in the environment. J Neurosci 27: 7705–7716, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin DW, Selen LP, Franklin S, Wolpert DM. Selection and control of limb posture for stability. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2013: 5626–5629, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidler J, Nichols D, Pelliccio M, Brady K, Campbell DD, Kahn JH, Hornby TG. Multicenter randomized clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of the Lokomat in subacute stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 23: 5–13, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housman SJ, Scott KM, Reinkensmeyer DJ. A randomized controlled trial of gravity-supported, computer-enhanced arm exercise for individuals with severe hemiparesis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 23: 505–514, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang FC, Patton JL, Mussa-Ivaldi FA. Manual skill generalization enhanced by negative viscosity. J Neurophysiol 104: 2008–2019, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluzik J, Diedrichsen J, Shadmehr R, Bastian AJ. Reach adaptation: what determines whether we learn an internal model of the tool or adapt the model of our arm? J Neurophysiol 100: 1455–1464, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TD, Ishikura T, Kegel S, Gonzalez D, Passmore S. Head-putter coordination patterns in expert and less skilled golfers. J Mot Behav 40: 267–272, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Cramer SC, Reinkensmeyer DJ. Learning to perform a new movement with robotic assistance: comparison of haptic guidance and visual demonstration. J Neuroeng Rehabil 3: 20, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo AC, Guarino PD, Richards LG, Haselkorn JK, Wittenberg GF, Federman DG, Ringer RJ, Wagner TH, Krebs HI, Volpe BT, Bever CT Jr, Bravata DM, Duncan PW, Corn BH, Maffucci AD, Nadeau SE, Conroy SS, Powell JM, Huang GD, Peduzzi P. Robot-assisted therapy for long-term upper-limb impairment after stroke. N Engl J Med 362: 1772–1783, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüttgen J, Heuer H. The influence of haptic guidance on the production of spatio-temporal patterns. Hum Mov Sci 31: 519–528, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüttgen J, Heuer H. The influence of robotic guidance on different types of motor timing. J Mot Behav 45: 249–258, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchal-Crespo L, McHughen S, Cramer SC, Reinkensmeyer DJ. The effect of haptic guidance, aging, and initial skill level on motor learning of a steering task. Exp Brain Res 201: 209–220, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchal-Crespo L, Reinkensmeyer DJ. Haptic guidance can enhance motor learning of a steering task. J Mot Behav 40: 545–556, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchal-Crespo L, Reinkensmeyer DJ. Review of control strategies for robotic movement training after neurologic injury. J Neuroeng Rehabil 16: 20, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchal-Crespo L, van Raai M, Rauter G, Wolf P, Riener R. The effect of haptic guidance and visual feedback on learning a complex tennis task. Exp Brain Res 231: 277–291, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley E, Duncan T. Psychometric properties of the intrinsic motivation inventory in a competitive sport setting: a confirmatory factor analysis. Res Q Exerc Sport 60: 48–58, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley E, Wraith S, Duncan TE. Self-efficacy, perceptions of success, and intrinsic motivation for exercise. J Appl Soc Psychol 21: 139–155, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Milot MH, Marchal-Crespo L, Green CS, Cramer SC, Reinkensmeyer DJ. Comparison of error-amplification and haptic-guidance training techniques for learning of a timing-based motor task by healthy individuals. Exp Brain Res 201: 119–131, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JL, Stoykov ME, Kovic M, Mussa-Ivaldi FA. Evaluation of robotic training forces that either enhance or reduce error in chronic hemiparetic stroke survivors. Exp Brain Res 168: 368–383, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinkensmeyer DJ, Housman SJ. “If I can't do it once, why do it a hundred times?”: connecting volition to movement success in a virtual environment motivates people to exercise the arm after stroke. Virtual Rehabilitation 2007: 44–48, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson EM, Cohen DA. Understanding consolidation through the architecture of memories. Neuroscientist 12: 261–271, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM. Control and information in the intrapersonal sphere: an extension of cognitive evaluation theory. J Pers Soc Psychol 43: 450–461, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Saemi E, Porter JM, Ghotbi-Varzaneh A, Zarghami M, Maleki F. Knowledge of results after relatively good trials enhances self-efficacy and motor learning. Psychol Sport Exerc 13: 378–382, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schweighofer N, Han CE, Wolf SL, Arbib MA, Winstein CJ. A functional threshold for long-term use of hand and arm function can be determined: predictions from a computational model and supporting data from the extremity constraint-induced therapy evaluation (EXCITE) trial. Phys Ther 89: 1327–1336, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah PK, Gerasimenko Y, Shyu A, Lavrov I, Zhong H, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. Variability in step training enhances locomotor recovery after a spinal cord injury. Eur J Neurosci 36: 2054–2062, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trempe M, Sabourin M, Proteau L. Success modulates consolidation of a visuomotor adaptation task. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 38: 52–60, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Asseldonk EH, Wessels M, Stienen AH, van der Helm FC, van der Kooij H. Influence of haptic guidance in learning a novel visuomotor task. J Physiol (Paris) 103: 276–285, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstein CJ, Pohl PS, Lewthwaite R. Effects of physical guidance and knowledge of results on motor learning: support for the guidance hypothesis. Res Q Exerc Sport 65: 316–323, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HG, Miyamoto YR, Castro LN, Olveczky BP, Smith MA. Temporal structure of motor variability is dynamically regulated and predicts motor learning ability. Nat Neurosci 17: 321–321, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]