Abstract

Aims

Aging is a major risk factor for carotid artery disease and stroke. Endothelin-1 (ET-1) and angiotensin II (Ang II) are important modifiers of vascular disease, partly through increased activity of NADPH oxidase and vasoconstrictor prostanoids. Since the renin-angiotensin and endothelin systems become activated with age, we hypothesized that aging affects NADPH oxidase- and prostanoid-dependent contractions to ET-1 and Ang II.

Methods

Carotid artery rings of young (4 month-old) and old (24 month-old) C57BL6 mice were pretreated with the NO synthase inhibitor L-NAME to exclude differential effects of NO. Contractions to ET-1 and Ang II were determined in the presence and absence of NADPH oxidase (gp91ds-tat) or thromboxane-prostanoid receptor (SQ 29,548) inhibition. Gene expression of endothelin and angiotensin receptors was measured by qPCR.

Key findings

Aging reduced ET-1-induced contractions and diminished ETA but increased ETB receptor gene expression levels. Gp91ds-tat inhibited contractions to ET-1 in young and to a greater extent old animals, whereas SQ 29,548 had no effect. Ang II-induced contractions were weak compared to ET-1 and unaffected by aging, gp91ds-tat, and SQ 29,548. Aging had also no effect on AT1A and AT1B receptor gene expression levels.

Significance

Aging in carotid arteries decreases ETA receptor gene expression and responsiveness to ET-1, which nevertheless becomes increasingly dependent upon NAPDH oxidase activity with age; responses to Ang II and gene expression of its receptors are however unaffected. These findings suggest that physiological aging differentially regulates functional responses to G protein-coupled receptor agonists and the signaling pathways associated with their activation.

Keywords: age, atherosclerosis, artery, cyclooxygenase, dementia, GPCR, gp91ds-tat, NADPH, Nox, oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species, ROS, prostanoid, stroke, superoxide, vascular

Introduction

Aging is a main risk factor for the development of carotid artery atherosclerosis and its clinical consequences such as stroke and dementia, and the associated social burden of disability and cognitive impairment becomes increasingly important as people live longer [1]. Arterial stiffening is a hallmark of the vascular aging process, which is characterized by dysregulated production of collagen, elastin and other structural proteins of the vascular wall, as well as by increased vascular tone [2]. Vasoconstrictor mediators that are involved in the physiology of vascular aging include endothelin-1 (ET-1) and angiotensin II (Ang II) [2, 3], which facilitate vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, fibrosis and remodeling [4, 5], thus further promoting atherosclerosis and arterial stiffening [2, 4, 5]. In fact, increased expression of ET-1 [6, 7] and Ang II [8] has been found in carotid and other arteries of otherwise healthy aged animals. Furthermore, inhibiting the action of either ET-1 [9] or Ang II [10–12] has been proven effective in partially counteracting the deleterious effects resulting from physiological aging in the cardiovascular system.

ET-1 is the predominant isoform of three distinct isopeptides constitutively secreted by endothelial and other vascular cells [4], and the most potent endogenous vasoconstrictor known [13]. Ang II is the major bioactive peptide of the renin-angiotensin system and is produced both systemically and locally within the vascular wall [5]. ET-1 and Ang II induce vascular effects by activating specific G protein-coupled receptors, endothelin ETA/ETB and angiotensin AT1/AT2 receptors, respectively, resulting in the activation of similar signaling pathways [4, 5]. Moreover, Ang II stimulates vascular production of ET-1 [14] and causes hypertrophic remodeling, which can be prevented by blocking ETA receptors [15], indicating that both vasoactive systems functionally interact. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by NAPDH oxidase as well as cyclooxygenase (COX)-derived vasoconstrictor prostanoids are part of the complex signaling network stimulated by ET-1 [4] and Ang II [5, 10, 16]. Moreover, increased expression of NAPDH oxidase and COX, as well as the augmented vascular activity of ROS and prostanoids, has been demonstrated to occur with vascular aging [10, 17–20].

Despite the important clinical and economic complications that arise from carotid artery disease [1], physiological effects of aging in this vascular bed are poorly understood. In the common carotid artery of adult mice, basal nitric oxide (NO) production is particularly high [21], and NO-mediated vasodilator responses are only slightly impaired with aging compared to other vascular beds [22]. Whether aging of carotid arteries also affects contractile responses to ET-1 and Ang II is unknown, although both contractile peptides have been implicated in age-dependent vascular stiffening and disease [2, 4, 5]. Because the vascular activity of NADPH oxidase-derived ROS and vasoconstrictor prostanoids is regulated by ET-1 and Ang II [4, 5, 10, 16] and increases with aging [10, 17–20], we hypothesized that these pathways are integral to the age-dependent alterations in responsiveness to ET-1 and Ang II. We therefore set out to investigate the role of NADPH oxidase and COX-derived prostanoids in ET-1- and Ang II-mediated contractility of common carotid arteries from young and old healthy mice. In addition, we determined gene expression levels of the receptors for ET-1, Ang II and selected NADPH oxidase proteins.

Materials and Methods

Materials

ET-1 was from American Peptide (Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and Ang II was from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH, USA). The thromboxane-prostanoid (TP) receptor antagonist[lS-[la,2a(Z),3a,4a]]-7-[3-[[2-[(phenylamino)carbonyl]hydrazino] methyl]-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-2-yl]-5-heptenoic acid (SQ 29,548) [23] and the NO synthase inhibitor L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester (L-NAME) were from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA), and the NADPH oxidase-selective inhibitor gp91ds-tat [24] was from Anaspec (Fremont, CA, USA). All other drugs were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Stock solutions were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and diluted in physiological saline solution (PSS, composition in mmol/L: 129.8 NaCl, 5.4 KC1, 0.83 MgS04, 0.43 NaH2P04, 19 NaHC03, 1.8 CaCl2, and 5.5 glucose; pH 7.4) to the required concentrations before use.

Animals

Male mice (C57BL6, Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were sacrificed at 4 (mean body weight 31.2±1.2g, young) and 24 (mean body weight 30.8±1.1g, old) months of age by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (2.2mg/g body weight). Animals were kept at the University of New Mexico Animal Resource Facility on a 12 hour light-dark cycle and received standard rodent chow and water ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the University of New Mexico Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Isolated vessel preparation

Immediately after sacrifice, common carotid arteries were isolated, excised, and carefully cleaned of adherent connective tissue and fat in cold (4°C) PSS under a dissecting microscope. Arteries were transferred to organ chambers of a Mulvany-Halpern myograph (620M Multi Wire Myograph System, Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark) containing PSS, and mounted by threading two 25 μn tungsten wires through the vessel lumen and securing each wire to a mounting jaw. Each jaw was connected either to a micropositioner or to a force transducer for recording of isometric tension using a PowerLab 8/35 data acquisition system and LabChart Pro software (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA).

Vascular function experiments

Arteries were allowed to equilibrate for 30 min in PSS (37°C, pH 7.4, bubbled with 21% O2, 5% CO2 and balanced N2), and stretched stepwise until the optimal passive tension for generating force during isometric contraction was reached. After equilibrating for an additional 45 min, functional integrity of the vascular smooth muscle was confirmed by repeatedly exposing vessels to KC1 (PSS with equimolar substitution of 60 mmol/L potassium for sodium). These reference contractions were comparable between groups (7.2±0.4 mN and 7.9±0.3 mN in carotid arteries from young and old animals, respectively). Vessels were then incubated with the NO synthase inhibitor L-NAME (300 μmol/L for 30 min) to unmask contractile effects of ET-1 and Ang II [25, 26], and to exclude ETB or AT2 receptor-stimulated NO release [4, 5] as well as potential differences in NO bioavailability between age groups [3, 27] that would complicate analysis of agonist-mediated contractions. A subset of arteries was additionally incubated with the NADPH oxidase-selective inhibitor gp91ds-tat (3 μmol/L) [24] or the TP receptor antagonist SQ 29,548 (1 μmol/L) [23] for 30 min. Thereafter, responses to cumulative concentrations of ET-1 (0.1–100 nmol/L) or to Ang II (100 nmol/L) were recorded. A single concentration of Ang II that elicits a maximal contraction was chosen because in mouse arteries the contractile response to Ang II is not sustained but undergoes rapid desensitization with a complete loss of tension within minutes [26].

Quantitation of carotid artery gene expression levels

Total RNA was extracted from carotid arteries and reverse transcribed as described [28]. Quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green-based detection of amplified gene-specific cDNA fragments on a 7500 FAST real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with the following sets of primers: 5′-GAA GGA CTG GTG GCT CTT TG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTT CTC GAC GCT GTT TGA GG-3′ (reverse) for amplification of a specific cDNA fragment encoding for murine ETA receptor (GenBank ID: BC008277); 5′-CGG TAT GCA GAT TGC TTT GA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAC CTG TGT GGA TTG CTC TG-3′ (reverse) for amplification of a specific cDNA fragment encoding for murine ETB receptor (GenBank ID: BC026553); 5′-GCG GTC TCC TTT TGA TTT CC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAA AGG GCT CCT GAA ACT TG-3′ (reverse) for amplification of a specific cDNA fragment encoding for murine AT1A receptor (GenBank ID: NM_177322.3); 5′-TAT TTT CCC CAG AGC AAA GC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGT TGC TTC CTT GTC CCT TG-3′ (reverse) for amplification of a specific cDNA fragment encoding for murine AT1B receptor (GenBank ID: NM_175086.3); 5′-CCA GCA CTA TGT GTA CAT GT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCA ATG GGG AAC ATC TCC TT-3′ (reverse) for amplification of a specific cDNA fragment encoding for murine p47phox (GenBank ID: NM_010876.3); 5′-TTC ACC ACC ATG GAG AAG GC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGC ATG GAC TGT GGT CAT GA-3′ (reverse) for amplification of a specific cDNA fragment encoding for murine GAPDH (GenBank ID: NM008084), which served as the house-keeping control. Relative gene expression was calculated based on the 2−∆CT method [29].

Data calculation and statistical analyses

Contractions are expressed as percentage of the maximal contraction to KC1 (60 mmol/T). Area under the curve (AUC), EC50 values (as negative logarithm, pD2) and maximal effects (Emax) were calculated by curve fitting as described by deLean et al. [30]. Data was analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test, or unpaired Student’s t-test as appropriate (Prism version 5.0 for Macintosh, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Values are expressed as the mean±SEM of independent experiments; n equals the number of animals used. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effect of aging on contractions to ET-1 and Ang II in the common carotid artery

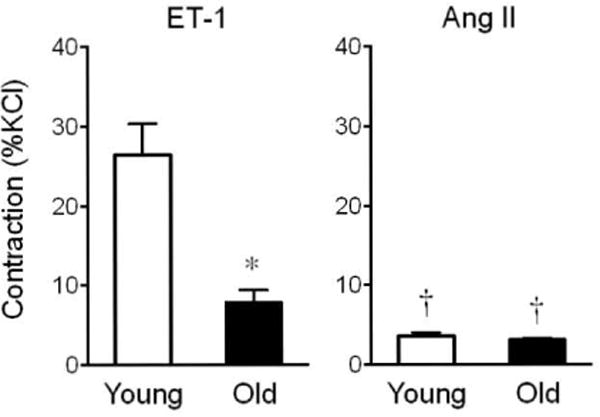

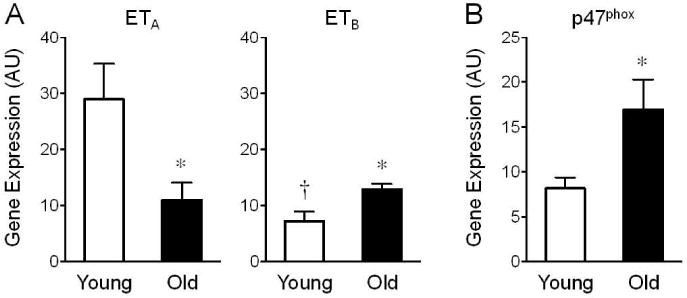

We first examined whether aging affects contractions induced by ET-1 and Ang II in arteries of mice at 4 months (young) and 24 months (old) of age. Contractions to ET-1 (100 nmol/L) were markedly greater in vessels from young compared to old mice (3-fold difference, 26±4% KC1 vs. 9±2% KC1, n=4–6, p<0.01, Figure 1). This age-dependent decrease in contractility was associated with reduced sensitivity to ET-1 (pD2 values) in arteries from old mice (p<0.01 vs. young mice, Table 1). Furthermore, aging diminished ETA receptor gene expression levels by 62%, whereas ETB receptor gene expression levels increased by 79% (n=3–4, p<0.05 vs. young mice, Figure 2A). Compared to ET-1-induced responses, contractions to equimolar concentrations of Ang II (100 nmol/L) were 7-fold and 3-fold weaker in vessels from young and old mice, respectively (n=4–6, p<0.05, Figure 1). Moreover, unlike responses to ET-1, aging neither affected Ang II-induced contractions (Figure 1) nor gene expression levels of the AT1A receptor (26±8 AU vs. 28±15 AU, n=4, p=n.s.) or the AT1B receptor (5±1 AU vs. 5±1 AU, n=3–4, p=n.s.).

Figure 1. Effect of aging on contractions to endothelin-1 and angiotensin II in the carotid artery.

Responses to equimolar concentrations (100 nmol/L) of endothelin-1 (ET-1, left panel) and angiotensin II (Ang II, right panel) were determined in arteries from young (4 months) and old (24 months) mice. *p<0.01 vs. young animals; †p<0.05 vs. ET-1 (n=4–6).

Table 1.

Area under the curve (AUC), maximal responses (Emax), and pD2 values of endothelin-1-induced contractions.

| Inhibitor | AUC (AU) | Emax (%KC1) | pD2 (-log mol/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | ||||

| untreated | 40.3±5.4 | 26.2±3.8 | 8.54±0.02 | |

| gp91ds-tat | 21.1±4.5* | 15.3±3.4* | 8.38±0.03 | |

| SQ 29,548 | 45.5±8.6 | 30.7±4.4 | 8.43±0.10 | |

|

| ||||

| Old | ||||

| untreated | 10.4±2.1† | 8.9±1.8† | 8.02±0.07† | |

| gp91ds-tat | 3.7±1.3*† | 3.4±l.*† | 7.85±0.15† | |

| SQ 29,548 | 7.1±2.1† | 6.3±1.7† | 7.89±0.09† | |

Responses were obtained in young (4 months) and old (24 months) mice in the presence and absence of the NADPH oxidase-selective inhibitor gp91ds-tat (3 μmol/L) or the TP receptor antagonist SQ 29,548 (1 μmol/L). Values were calculated by fitting of dose-response curves [30]. AUC is expressed as arbitrary units (AU).

p<0.05 vs. untreated

p<0.01 vs. young mice (n=4–6).

Figure 2. Age-dependent gene expression levels of ETA and ETB receptors (A) and the NAPDH oxidase adaptor protein p47phox (B) in the carotid artery.

Gene expression levels in young (4 months) and old (24 months) mice were determined by quantitative PCR and are expressed as arbitrary units (AU). *p<0.05 vs. young animals; †p<0.05 vs. ETA (n=3–4).

Age-dependent role of NADPH oxidase in ET-1-induced contractions

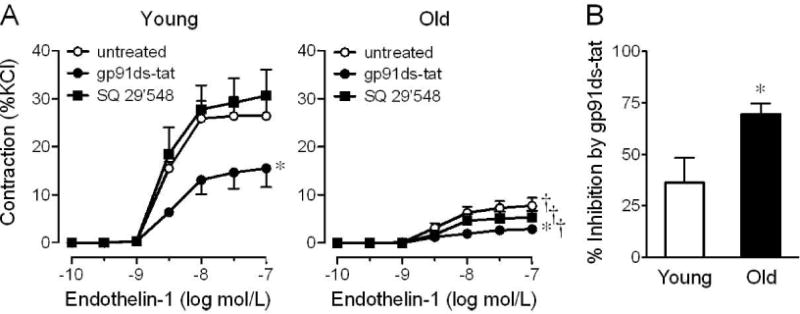

We next determined whether contractions to ET-1 and Ang II involve the vascular activity of NADPH oxidase and COX-derived vasoconstrictor prostanoids, both of which increase with aging [10, 17–20] and can be stimulated by ET-1 and Ang II [4, 5, 10, 16]. In young mice, inhibition of NADPH oxidase using its selective inhibitor gp91ds-tat (3 μmol/L) [24] reduced contractions to ET-1 (from 26±3% KC1 to 15±3% KC1, n=4, p<0.05, Figure 3A and Table 1). This effect was even more pronounced in old mice (from 8±1% KC1 to 3±1% KC1, n=6, p<0.01, Figure 3A and Table 1). Analysis of paired vascular rings from the same mouse treated with and without gp91ds-tat revealed that inhibition of NADPH oxidase reduces ET-1 (100 nmol/L)-induced contractions by 36±12% in young animals and by 70±5% in old animals (n=4, p<0.05, Figure 3B), indicating that ET-1-dependent contractions are increasingly dependent upon functional NAPDH oxidase with aging. Similarly, gene expression levels of p47phox, an adaptor protein of the NADPH oxidase complex whose interaction with Nox1/Nox2 is required for stimulus-induced ROS production but prevented by gp91ds-tat treatment, increase with age by 2-fold (n=3–4, p<0.05, Figure 2B). Gene expression levels of the transmembrane scaffolding protein p22phox were unchanged in arteries from young and old mice (not shown).

Figure 3. Effect of aging and role of NADPH oxidase and vasoconstrictor prostanoids in endothelin-1-induced contractions in the carotid artery.

A, Concentration-dependent responses to endothelin-1 in arteries of young (4 months) and old (24 months) mice were determined in the presence and absence of the NADPH oxidase-selective inhibitor gp91ds-tat (3 μmol/L) or the TP receptor antagonist SQ 29,548 (1 umol/L). B, Gp91ds-tat-mediated relative inhibition of contractions to ET-1 (100 nmol/L) was calculated in paired carotid artery rings of individual mice. *p<0.05 vs. untreated; †p<0.05 vs. young animals (n=4–6).

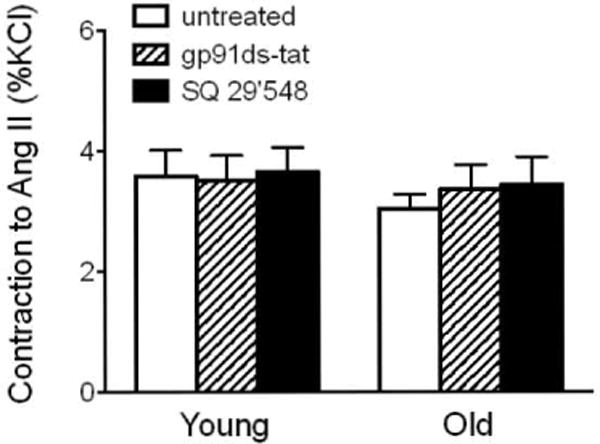

In contrast to NADPH oxidase activity, inhibition of vasoconstrictor prostanoid signaling using the selective TP receptor antagonist SQ 29,548 (1 μmol/L) [23] did not affect ET-1-induced contractions independent of age (Figure 3A and Table 1). Moreover, inhibition of NAPDH oxidase activity or TP receptor signaling had no effect on the contractile responses to Ang II in arteries from either young or old mice (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Age-dependent, Ang II-induced contractions and inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity or TP receptor signaling in the carotid artery.

Contractions to Ang II (100 nmol/L) in young (4 months) and old (24 months) mice were determined in the presence and absence of the NADPH oxidase-selective inhibitor gp91ds-tat (3 umol/L) or the TP receptor antagonist SQ 29,548 (1 umol/L; n=4–7).

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that physiological aging in the murine common carotid artery is associated with decreased responsiveness to ET-1, which however increasingly depends on functional NADPH oxidase activity with advancing age. Surprisingly, aging had no effect on contractility to Ang II, which was also independent of NAPDH oxidase activity, regardless of age. This finding was unexpected since both ET-1 and Ang II activate similar signaling pathways, functionally interact in the vasculature [14, 15], and have been implicated in age-dependent atherosclerosis progression, vascular stiffening and disease [2, 4, 5]. It is therefore likely that aging differentially regulates responses to vasoactive agonists and the signaling pathways involved, lending further support to the hypothesis that age-dependent functional changes may not be uniform throughout the vascular system. This is in line with studies in humans demonstrating that the initiation, rapidity of development, and phenotypic expression of atherosclerotic plaques varies greatly between different arteries depending on location, hemodynamics and arterial wall structure [31]. Accordingly, individual factors may explain why the common carotid artery is less susceptible to atherosclerotic plaque development than the bifurcation and the curved terminal part of the internal carotid artery [31, 32].

There is limited information whether and how physiological aging affects the regulation of vascular tone in carotid arteries, both in humans and in animals. Compared to other vascular beds, murine common carotid arteries are characterized by particularly high NO bioavailability [21]. Moreover, endothelium-dependent NO-mediated dilation as well as endothelial NO synthase expression are mostly preserved in old mice at 24 months of age [22], and only start to deteriorate as the animals age further [33, 34]. Although these findings are consistent with maintained NO bioavailability even at an advanced age, the present study now demonstrates profound age-dependent alterations in contractile responses to ET-1, suggesting that aging differentially regulates the activity of endothelial vasoactive factors known to be associated with age-dependent functional vascular injury and disease development [3, 27,31,32].

Aging is associated with increased local concentrations of ET-1 in the vascular wall of carotid arteries and other vascular beds [6, 7]. It has been suggested that increased formation of the constrictor peptide and its activity within the local vascular microenvironment may negatively affect receptor responsiveness or down-stream signaling pathways [4] that potentially lead to the reduced constrictor response to exogenous ET-1 in aged arteries as observed in the present and in previous studies [6, 35, 36]. Indeed, we found that not only the sensitivity to ET-1 but also ETA receptor gene expression levels in carotid arteries decline with aging. Interestingly, we also observed an age-dependent increase in gene expression levels of the ETB receptor, which generally mediates the release of the vasodilators prostacyclin and NO [4], although the latter pathway has been inhibited by L-NAME in our study.

Oxygen-derived free radicals have been implicated as playing a causative role in age-dependent endothelial cell dysfunction [3, 27]. In line with this concept, we observed that ET-1-induced contractions increasingly depend on superoxide-generating NAPDH oxidase activity with aging. Among other sources, such as uncoupled endothelial NO synthase, xanthine oxidase, and mitochondrial ROS formation [3, 27], increased expression as well as basal and substrate-stimulated activity of NADPH oxidase has been associated with enhanced oxidative stress during vascular aging [17, 18, 33, 37]. The present study extends these findings by demonstrating that ET-1-induced vascular NADPH oxidase activity, as well as gene expression of p47phox, an adaptor protein of the NADPH oxidase complex, increases in common carotid arteries of aged mice. ET-1 has previously been found to stimulate vascular superoxide production by NADPH oxidase under healthy conditions [38, 39] as well as in the presence of hypertension [38] and atherosclerosis [40]. Moreover, ET-1-induced contractions in rat aorta and renal arteries are sensitive to apocynin [39, 41]; the latter finding may have to be interpreted with caution, since apocynin, depending on the concentration used, can also act as a NAPDH oxidase-independent ROS inhibitor due to potent antioxidant and other effects [42]. Here, we used the selective NAPDH oxidase inhibitor gp91ds-tat (a 9-amino acid peptide from gp91 linked to an 11-amino acid cell-penetrating tat peptide of HIV) that prevents the assembly of Nox1 and Nox2 with p47phox, which is necessary for full activation of NADPH oxidase [24, 42]. Our results thus not only indicate that vascular responses to ET-1 are indeed NADPH oxidase-dependent and mediated by the inducible Nox1 and/or Nox2 isoforms, but also that the increased vascular p47phox gene expression levels with aging may be functionally relevant for the enhanced NADPH oxidase activity induced by ET-1.

COX-dependent formation of vasoconstrictor prostanoids is importantly involved in the regulation of vascular tone, both as endothelium-dependent contracting factor (EDCF) [19, 20, 43] and as adipose-derived contracting factor (ADCF) released from perivascular adipose [44]. Similar to the amplified generation of ROS, the vascular activity of COX-derived vasoconstrictor prostanoids increases with vascular aging in certain species [3, 27]. In the aorta of hamsters, TP receptor-mediated contractions in response to prostaglandin F2α increase in old compared to young animals [20], and enhanced responses to vasoconstrictor prostanoids in the aorta of aged rats are augmented due to increased ROS formation [19]. Moreover, prostanoid-dependent TP receptor activation can increase vascular ROS production by NADPH oxidase [45, 46]. Although endothelium-dependent contractions to vasoconstrictor prostanoids are highly potent in carotid arteries from adult mice [43], we found that inhibition of prostanoid signaling using a selective TP receptor antagonist did not affect contractions to ET-1, independent of age. Taken together, these findings suggest that TP receptor activation is not involved in the age-dependent increased contribution of NAPDH oxidase to ET-1-mediated responses, and that ET-1 selectively activates distinct signaling pathways in carotid arteries that are associated with functional aging.

We have previously shown that contractile responses to Ang II in murine common carotid arteries of adult mice are weak even following acute inhibition of NO production and that contractions undergo rapid desensitization [26]. Although the renin-angiotensin system has been implicated in age-dependent impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation [5, 10] and despite the fact that aging substantially increases Ang II-mediated concentrations in the aorta from nonhuman primates [8], we unexpectedly observed that in carotid arteries, Ang II-induced contractions as well as gene expression of the two isoforms of the rodent AT1 receptor that mediate constrictor effects of Ang II, AT1A and AT1B [5], remain unaffected by aging. Unlike other vascular beds [5, 10, 47, 48], responses of the common carotid artery to Ang II were also independent of functional NADPH oxidase and TP receptor signaling, suggesting that Ang II-dependent regulation of carotid artery tone in mice is maintained even at advanced age. The tachyphylaxis of the weak responses to Ang II poses a limitation to the current study since it did not allow study of the arteries’ sensitivity to Ang II. Furthermore, the activation of other signaling pathways such as phospholipases C and D [5] may underlie the weak constrictor response to Ang II in murine common carotid arteries.

Conclusions

The present study provides evidence that the physiological aging process has pronounced and differential effects on functional responses to G protein-coupled receptor agonists and the signaling pathways associated with their activation. In carotid arteries, we observed substantial age-dependent changes in the responsiveness to ET-1 that partly involved NAPDH oxidase-dependent pathways, whereas functional responses to Ang II as well as prostanoid signaling remained unaffected by aging.

Age-dependent increases in vascular tone, as well as induction of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, fibrosis and remodeling in response to both ET-1 and Ang II have been implicated in atherosclerosis progression and vascular stiffening [2–5]. Pharmacologic inhibition of the renin angiotensin-system has been proven effective in the prevention of stroke and dementia in hypertensive patients [1]. Moreover, observational studies have shown that carotid artery intima-media thickness (IMT) positively correlates with plasma ET-1 concentrations in hypertensive [49, 50] and in diabetic [51] patients, and that carotid artery IMT is positively associated with plasma ET-1 levels in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome [52]. Supporting the findings of the present study, the relationship between plasma ET-1 concentration and carotid artery IMT also appears to be dependent on plasma antioxidant capacity [50], suggesting that the deleterious vascular effects of ET-1 are partly ROS-mediated. Whether interfering with the vascular activity of ET-1 can prevent age-induced carotid artery disease and the increased risk for stroke and cognitive impairment associated with it awaits future studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Chelin Hu and Daniel F. Cimino for expert technical assistance. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA127731 and CA163890 to ERP), Dedicated Health Research Funds from the University of New Mexico School of Medicine allocated to the Signature Program in Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases (to ERP), and the Swiss National Science Foundation (grants 135874 & 141501 to MRM and grants 108258 & 122504 to MB). NCF was supported by a National Institutes of Health training grant (T32 HL07736).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Chemical compounds studied in this article:

Angiotensin II (PubChem CID: 172198); Endothelin-1 (PubChem CID: 16212950); L-NG-nitroarginine mathyl ester (PubChem CID: 39836); SQ 29,548 (PubChem CID: 5271)

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, Launer LJ, Laurent S, Lopez OL, Nyenhuis D, Petersen RC, Schneider JA, Tzourio C, Arnett DK, Bennett DA, Chui HC, Higashida RT, Lindquist R, Nilsson PM, Roman GC, Sellke FW, Seshadri S. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011;42:2672–713. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zieman SJ, Melenovsky V, Kass DA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and therapy of arterial stiffness. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:932–43. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000160548.78317.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton M. Obesity and aging: determinants of endothelial cell dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460:825–37. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0860-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohan DE, Rossi NF, Inscho EW, Pollock DM. Regulation of blood pressure and salt homeostasis by endothelin. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:1–77. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00060.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C82–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barton M, Cosentino F, Brandes RP, Moreau P, Shaw S, Luscher TF. Anatomic heterogeneity of vascular aging: role of nitric oxide and endothelin. Hypertension. 1997;30:817–24. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goettsch W, Lattmann T, Amann K, Szibor M, Morawietz H, Munter K, Muller SP, Shaw S, Barton M. Increased expression of endothelin-1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase isoform II in aging arteries in vivo: implications for atherosclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:908–13. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang M, Takagi G, Asai K, Resuello RG, Natividad FF, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Lakatta EG. Aging increases aortic MMP-2 activity and angiotensin II in nonhuman primates. Hypertension. 2003;41:1308–16. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000073843.56046.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortmann J, Amann K, Brandes RP, Kretzler M, Munter K, Parekh N, Traupe T, Lange M, Lattmann T, Barton M. Role of podocytes for reversal of glomerulosclerosis and proteinuria in the aging kidney after endothelin inhibition. Hypertension. 2004;44:974–81. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000149249.09147.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukai Y, Shimokawa H, Higashi M, Morikawa K, Matoba T, Hiroki J, Kunihiro I, Talukder HM, Takeshita A. Inhibition of renin-angiotensin system ameliorates endothelial dysfunction associated with aging in rats. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1445–50. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000029121.63691.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basso N, Cini R, Pietrelli A, Ferder L, Terragno NA, Inserra F. Protective effect of long-term angiotensin II inhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1351–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00393.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benigni A, Corna D, Zoja C, Sonzogni A, Latini R, Salio M, Conti S, Rottoli D, Longaretti L, Cassis P, Morigi M, Coffman TM, Remuzzi G. Disruption of the Ang II type 1 receptor promotes longevity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:524–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI36703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Tomobe Y, Kobayashi M, Mitsui Y, Yazaki Y, Goto K, Masaki T. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1988;332:411–5. doi: 10.1038/332411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barton M, Shaw S, d’Uscio LV, Moreau P, Luscher TF. Angiotensin II increases vascular and renal endothelin-1 and functional endothelin converting enzyme activity in vivo: role of ETA receptors for endothelin regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;238:861–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreau P, d’Uscio LV, Shaw S, Takase H, Barton M, Luscher TF. Angiotensin II increases tissue endothelin and induces vascular hypertrophy: reversal by ET(A)-receptor antagonist. Circulation. 1997;96:1593–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohnaka K, Numaguchi K, Yamakawa T, Inagami T. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 by angiotensin II in cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 2000;35:68–75. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oudot A, Martin C, Busseuil D, Vergely C, Demaison L, Rochette L. NADPH oxidases are in part responsible for increased cardiovascular superoxide production during aging. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:2214–22. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donato AJ, Eskurza I, Silver AE, Levy AS, Pierce GL, Gates PE, Seals DR. Direct evidence of endothelial oxidative stress with aging in humans: relation to impaired endothelium-dependent dilation and upregulation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Circ Res. 2007;100:1659–66. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000269183.13937.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi Y, Man RY, Vanhoutte PM. Two isoforms of cyclooxygenase contribute to augmented endothelium-dependent contractions in femoral arteries of 1-year-old rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29:185–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong SL, Leung FP, Lau CW, Au CL, Yung LM, Yao X, Chen ZY, Vanhoutte PM, Gollasch M, Huang Y. Cyclooxygenase-2-derived prostaglandin F2alpha mediates endothelium-dependent contractions in the aortae of hamsters with increased impact during aging. Circ Res. 2009;104:228–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.179770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crauwels HM, Van Hove CE, Herman AG, Bult H. Heterogeneity in relaxation mechanisms in the carotid and the femoral artery of the mouse. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;404:341–51. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00619-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Modrick ML, Kinzenbaw DA, Chu Y, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma protects against vascular aging. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R1184–90. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00557.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogletree ML, Harris DN, Greenberg R, Haslanger MF, Nakane M. Pharmacological actions of SQ 29,548, a novel selective thromboxane antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985;234:435–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rey FE, Cifuentes ME, Kiarash A, Quinn MT, Pagano PJ. Novel competitive inhibitor of NAD(P)H oxidase assembly attenuates vascular 0(2)(−) and systolic blood pressure in mice. Circ Res. 2001;89:408–14. doi: 10.1161/hh1701.096037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Widmer CC, Mundy AL, Kretz M, Barton M. Marked heterogeneity of endothelin-mediated contractility and contraction dynamics in mouse renal and femoral arteries. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231:777–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kretz M, Mundy AL, Widmer CC, Barton M. Early aging and anatomic heterogeneity determine cyclooxygenase-mediated vasoconstriction to angiotensin II in mice. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;48:30–3. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000242061.18981.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seals DR, Jablonski KL, Donato AJ. Aging and vascular endothelial function in humans. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011;120:357–75. doi: 10.1042/CS20100476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer MR, Field AS, Kanagy NL, Barton M, Prossnitz ER. GPER regulates endothelin-dependent vascular tone and intracellular calcium. Life Sci. 2012;91:623–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeLean A, Munson PJ, Rodbard D. Simultaneous analysis of families of sigmoidal curves: application to bioassay, radioligand assay, and physiological dose-response curves. Am J Physiol. 1978;235:E97–102. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.2.E97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalager S, Paaske WP, Kristensen IB, Laurberg JM, Falk E. Artery-related differences in atherosclerosis expression: implications for atherogenesis and dynamics in intima-media thickness. Stroke. 2007;38:2698–705. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.486480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solberg LA, Eggen DA. Localization and sequence of development of atherosclerotic lesions in the carotid and vertebral arteries. Circulation. 1971;43:711–24. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.43.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Durrant JR, Seals DR, Connell ML, Russell MJ, Lawson BR, Folian BJ, Donato AJ, Lesniewski LA. Voluntary wheel running restores endothelial function in conduit arteries of old mice: direct evidence for reduced oxidative stress, increased superoxide dismutase activity and down-regulation of NADPH oxidase. J Physiol. 2009;587:3271–85. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.169771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fleenor BS, Seals DR, Zigler ML, Sindler AL. Superoxide-lowering therapy with TEMPOL reverses arterial dysfunction with aging in mice. Aging Cell. 2012;11:269–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00783.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishihata A, Katano Y, Morinobu S, Endoh M. Influence of aging on the contractile response to endothelin of rat thoracic aorta. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;200:199–201. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90689-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shipley RD, Muller-Delp JM. Aging decreases vasoconstrictor responses of coronary resistance arterioles through endothelium-dependent mechanisms. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:374–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takenouchi Y, Kobayashi T, Matsumoto T, Kamata K. Gender differences in age-related endothelial function in the murine aorta. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li L, Fink GD, Watts SW, Northcott CA, Galligan JJ, Pagano PJ, Chen AF. Endothelin-1 increases vascular superoxide via endothelin(A)-NADPH oxidase pathway in low-renin hypertension. Circulation. 2003;107:1053–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051459.74466.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loomis ED, Sullivan JC, Osmond DA, Pollock DM, Pollock JS. Endothelin mediates superoxide production and vasoconstriction through activation of NADPH oxidase and uncoupled nitric-oxide synthase in the rat aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:1058–64. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cerrato R, Cunnington C, Crabtree MJ, Antoniades C, Pernow J, Channon KM, Bohm F. Endothelin-1 increases superoxide production in human coronary artery bypass grafts. Life Sci. 2012;91:723–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Just A, Whitten CL, Arendshorst WJ. Reactive oxygen species participate in acute renal vasoconstrictor responses induced by ETA and ETB receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F719–28. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00506.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brandes RP, Weissmann N, Schroder K. NADPH oxidases in cardiovascular disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:687–706. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Traupe T, Lang M, Goettsch W, Munter K, Morawietz H, Vetter W, Barton M. Obesity increases prostanoid-mediated vasoconstriction and vascular thromboxane receptor gene expression. J Hypertens. 2002;20:2239–45. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200211000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meyer MR, Fredette NC, Barton M, Prossnitz ER. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle tone by adipose-derived contracting factor. PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079245. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang M, Song P, Xu J, Zou MH. Activation of NAD(P)H oxidases by thromboxane A2 receptor uncouples endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:125–32. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bayat H, Schroder K, Pimentel DR, Brandes RP, Verbeuren TJ, Cohen RA, Jiang B. Activation of thromboxane receptor modulates interleukin-1 betainduced monocyte adhesion–a novel role of Nox1. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:1760–6. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawada N, Dennehy K, Solis G, Modlinger P, Hamel R, Kawada JT, Aslam S, Moriyama T, Imai E, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. TP receptors regulate renal hemodynamics during angiotensin II slow pressor response. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F753–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00423.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pfister SL, Nithipatikom K, Campbell WB. Role of superoxide and thromboxane receptors in acute angiotensin II-induced vasoconstriction of rabbit vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H2064–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01135.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katona E, Settakis G, Varga Z, Paragh G, Bereczki D, Fulesdi B, Pall D. Target-organ damage in adolescent hypertension. Analysis of potential influencing factors, especially nitric oxide and endothelin-1. J Neurol Sci. 2006;247:138–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skalska AB, Grodzicki T. Carotid atherosclerosis in elderly hypertensive patients: potential role of endothelin and plasma antioxidant capacity. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:538–44. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2009.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Migdalis IN, Kalogeropoulou K, Iiopoulou V, Varvarigos N, Karmaniolas KD, Mortzos G, Cordopatis P. Progression of carotid atherosclerosis and the role of endothelin in diabetic patients. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 2000;108:27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orio F, Jr, Palomba S, Cascella T, De Simone B, Di Biase S, Russo T, Labella D, Zullo F, Lombardi G, Colao A. Early impairment of endothelial structure and function in young normal-weight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4588–93. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]