Background: There is cross-talk between serotonin and melatonin hormones.

Results: There is evidence for unidirectional transactivation and a heteromer-specific signaling profile for formation of functional melatonin MT2 and serotonin 5-HT2C receptor heteromers.

Conclusion: A new potential target of the antidepressant agomelatine is identified.

Significance: The importance of binding of multitarget drugs to GPCR heteromers in psychiatric disorders is demonstrated.

Keywords: Cell Signaling, Depression, G Protein-coupled Receptor (GPCR), Molecular Pharmacology, Serotonin, GPCR, Heteromerization, Melatonin

Abstract

Inasmuch as the neurohormone melatonin is synthetically derived from serotonin (5-HT), a close interrelationship between both has long been suspected. The present study reveals a hitherto unrecognized cross-talk mediated via physical association of melatonin MT2 and 5-HT2C receptors into functional heteromers. This is of particular interest in light of the “synergistic” melatonin agonist/5-HT2C antagonist profile of the novel antidepressant agomelatine. A suite of co-immunoprecipitation, bioluminescence resonance energy transfer, and pharmacological techniques was exploited to demonstrate formation of functional MT2 and 5-HT2C receptor heteromers both in transfected cells and in human cortex and hippocampus. MT2/5-HT2C heteromers amplified the 5-HT-mediated Gq/phospholipase C response and triggered melatonin-induced unidirectional transactivation of the 5-HT2C protomer of MT2/5-HT2C heteromers. Pharmacological studies revealed distinct functional properties for agomelatine, which shows “biased signaling.” These observations demonstrate the existence of functionally unique MT2/5-HT2C heteromers and suggest that the antidepressant agomelatine has a distinctive profile at these sites potentially involved in its therapeutic effects on major depression and generalized anxiety disorder. Finally, MT2/5-HT2C heteromers provide a new strategy for the discovery of novel agents for the treatment of psychiatric disorders.

Introduction

The monoamine serotonin (5-HT)2 is derived from dietary tryptophan, which is transformed into 5-HT in diverse clusters of neurons in the gut and brain. 5-HT exerts its actions via 14 classes of receptors, which are broadly expressed in peripheral tissues and the central nervous system (1). Conversely, although the neurohormone melatonin is derived from 5-HT, it is mainly produced by the pineal gland in a circadian pattern under the control of hypothalamic nuclei, attaining peak levels during the night. Melatonin binds with high affinity to MT1 and MT2 receptors and with moderate affinity to the enzyme quinone reductase 2 (2). Both MT1 and MT2 receptors as well as all 14 classes of 5-HT receptor (except 5-HT3) belong to the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily. Despite structural similarities between melatonin and 5-HT, melatonin does not recognize 5-HT receptors, and 5-HT fails to bind MT1 or MT2 receptors. Furthermore, to date, there have been only a few reports of functional cross-talk between melatonergic and serotonergic transmission: for example, melatonin inhibits the ability of 5-HT to phase shift the suprachiasmatic circadian clock (3).

Recent studies have demonstrated other more direct modes of potential functional interaction expressed not only among signaling pathways but also operating directly at the level of GPCRs, which can assemble into heteromeric complexes (4). Such complexes frequently display functional properties distinct from those of the corresponding homomers and may even transduce novel and unique cellular responses. Moreover, several classes of GPCR heteromers have been associated with the pathogenesis and control of CNS disorders like 5-HT2A and metabotropic glutamate-2 receptor (mGluR2) heteromers in frontal cortex implicated in schizophrenia and in the actions of antipsychotics (5) and limbic dopamine D1 and D2 receptor heteromers incriminated in depressed states (6).

To date, the possible existence of heteromeric associations of MT1 or MT2 receptor with specific classes of 5-HT receptors has not been evaluated. Their putative existence is of particular interest inasmuch as the clinically proven antidepressant agomelatine, the first to possess a non-monoaminergic component of action, behaves as an agonist at Gi-coupled MT1 and MT2 receptors but as a neutral antagonist at Gq/11-coupled 5-HT2C receptors (7, 8). Intriguingly, although the affinity of agomelatine is substantially lower at 5-HT2C versus MT1 and MT2 in vitro, this apparent difference is much less pronounced in vivo, suggesting that it may exert its actions “synergistically” via these sites. Indeed, both 5-HT2C and MT1 and MT2 receptors are necessary for expression of the antidepressant actions of agomelatine, which cannot be reproduced either by melatonin or by selective 5-HT2C antagonists alone (9). For example, “synergistical” MT1, MT2, and 5-HT2C receptor-transduced actions of agomelatine may account for its induction of neurogenesis and BDNF synthesis as well as its modulation of glutamate release (for a review, see Ref. 9). In light of the above observations, the present studies explored the potential formation of heteromers between melatonin receptors and 5-HT2C receptors and specifically examined the functional profile of agomelatine at these sites.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Compounds

All chemicals and ligands were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich with the exception of pertussis toxin, which was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals, and 4-PPDOT, luzindole, and SB242084, which were purchased from Tocris. S20928, S21767, and agomelatine were a gift from the Institut de Recherches Servier (France).

Cell Culture and Transfection

HEK293 cells were grown in complete medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 4.5 g/liter glucose, 100 units/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, and 1 mm glutamine) (Invitrogen). Geneticin (G418) was added at 0.4 mg/ml to culture HEK293 cells stably expressing the MT2 receptor from the pcDNA3-CMV plasmid containing the neomycin resistance gene. Transient transfections were performed using JetPEI (Polyplus Transfection, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

DNA Constructs

The pcDNA3-CMV vectors expressing the human MT2 receptor, the double brilliance Rluc8-βARR2-YPet sensor, and the MT1-YFP and the 5-HT4d-YFP fusion proteins were described previously (10–12). The INI isoform of the human 5-HT2C coding region was fused at its C terminus with the coding region of Renilla luciferase (5-HT2C-Rluc) or the yellow fluorescent protein (5-HT2C-YFP) or at its N terminus with three HA tags (3xHA-5-HT2C). The 5-HT2C-S138N-Rluc mutant was obtained by mutagenesis from the 5-HT2C-Rluc plasmid. All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Immunoprecipitation

For co-immunoprecipitation assays, HEK293 cells were seeded in 10-cm dishes and co-transfected with 4 μg of each indicated plasmid. 48 h after transfection, crude membranes were prepared as described previously (13). Membrane proteins were solubilized with 1% digitonin, and receptors were precipitated with the indicated antibodies (14). Immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted with 4× Laemmli buffer and immunoblotted using the indicated primary antibodies. Immunoreactivity was revealed using secondary antibodies coupled to 680 or 770 nm fluorophores using the LI-COR Odyssey infrared fluorescence scanner (ScienceTec, France). For experiments with the pork plexus choroid, membranes were prepared, and melatonin receptors were labeled with 400 pm 2-[125I]iodomelatonin as described previously (15). Receptors were solubilized with 1% digitonin and precipitated with a mixture of three anti-5-HT2C rabbit antibodies (18461-10656, 18461-10657, and 18003-42961, Genway) or a pool of control preimmune serum, and immunoprecipitated radioactivity was determined.

Immunofluorescence

HeLa cells transiently expressing 6xMyc-MT2 and 3xHA-5-HT2C were fixed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Monoclonal anti-Myc antibody 9E10 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and polyclonal anti-HA antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) were applied followed by TRITC-tagged anti-mouse and fluorescein isothiocyanate-tagged anti-rabbit antibodies. Cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy.

In-cell Western Experiments

Cell surface expression of 5-HT2C receptors was evaluated by in-cell Western experiments in intact and Triton X-100-permeabilized HEK293 cells transiently expressing the 3xHA-5-HT2C construct and stably expressing the MT2 receptor (5-HT2C expression) or transiently expressing the 6xMyc-MT2 receptor (MT2 expression) as described previously (16) using the rabbit monoclonal anti-HA antibody (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Myc 9E10 antibody (1:500) and the LI-COR Odyssey infrared imaging system.

Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET) Measurement

For BRET donor saturation curves, HEK293 cells seeded in 12-well plates were transiently transfected with 50 ng of 5-HT2C-Rluc and 50–1950 ng of the corresponding YFP plasmids. 24 h after transfection, cells were transferred into a 96-well white Optiplate (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences) precoated with 10 μg/ml poly-l-lysine (Sigma) and incubated for another 24 h before BRET measurements. Luminescence and fluorescence were measured simultaneously using the lumino/fluorometer MithrasTM (Berthold) as described previously (11) using optimized filter settings (Rluc filter, 480 ± 10 nm; YFP filter, 540 ± 20 nm).

Intracellular Signaling Assays

HEK293 cells stably expressing 20–30 fmol of MT2/mg of protein and transiently expressing or not 20–30 fmol of 5-HT2C or HEK293 cells transiently expressing only 5-HT2C receptors were used. Inositol 1-phosphate (IP) levels were determined in cells stimulated with the indicated ligands for 1 h at 37 °C by homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence using the Cisbio IP-One Tb kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cyclic AMP levels were determined in cells treated with the indicated ligands for 30 min at room temperature in the absence or presence of 2 μm forskolin by homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence using the Cisbio cAMP femto Tb kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. IP and cAMP measurements were performed in triplicates, and experiments were repeated three to eight times. To determine ERK1/2 phosphorylation levels, cells were stimulated for 2, 5, 10, 15, and 30 min with 100 nm melatonin, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation was determined as described previously (16, 17).

Statistical Analysis

Results were analyzed by PRISM (GraphPad Software). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. of at least three experiments. Student's t test was applied for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Physical Interaction between 5-HT2C and MT1/MT2 Receptors

We first carried out co-immunoprecipitation experiments to assess a possible interaction between the human 5-HT2C and MT1 and MT2 receptors. These experiments revealed that 5-HT2C interacts with MT1 and MT2 in HEK293 cells co-expressing the respective receptors (Fig. 1, A and B). To further confirm the existence of these heteromeric complexes and to assess the propensity of heteromer formation, BRET experiments were performed. 5-HT2C was fused at its C terminus to the energy donor Rluc. C-terminal YFP fusion proteins (5-HT2C-YFP, MT1-YFP, MT2-YFP, and 5-HT4d-YFP) acted as energy acceptors (Fig. 1C). The expected hyperbolic donor saturation curve, reflecting a specific interaction between BRET donor and acceptor pairs, was observed for all receptor combinations except for the negative control 5-HT4d-YFP fusion protein for which a quasilinear increase in BRET reflecting a nonspecific interaction due to random collision was observed (18, 19). Determination of BRET50 values, corresponding to the saturation of 50% of BRET donors by BRET acceptors, revealed that the relative propensity of 5-HT2C to form heteromers with MT2 (BRET50 = 2.2 ± 0.4) is higher than with MT1 (BRET50 = 6.9 ± 1.5) or with itself (BRET50 = 8.8 ± 1.5), indicating preferential formation of MT2/5-HT2C heteromers. As shown by immunofluorescence staining, 5-HT2C expressed alone was mainly intracellular, and a significant amount of MT2 and 5-HT2C was present at the plasma membrane where both receptors colocalized (Fig. 1D). Formation of MT2/5-HT2C heteromers was further suggested by co-immunoprecipitation studies in human cortex and hippocampus, two regions shown previously to express melatonin and 5-HT2C receptors (20, 21) (data not shown). Heat-inactivated anti-MT2 antibodies were used as a negative control. Further evidence for the formation of MT2/5-HT2C heteromers was obtained from choroid plexus membranes, which are known to express significant amounts of 5-HT2C receptors. Melatonin receptors were labeled with 2-[125I]iodomelatonin, and protein complexes were solubilized and immunoprecipitated with anti-5-HT2C antibodies. As shown in Fig. 1E, significant amounts of radiolabeled melatonin receptors were precipitated with anti-5-HT2C antibodies as compared with a mixture of irrelevant control antibodies. Overall, our results indicate that 5-HT2C specifically interacts with MT2 in transfected HEK293 cells and in the cortex, hippocampus, and choroid plexus.

FIGURE 1.

Formation of MT1/5-HT2C and MT2/5-HT2C heteromers. A and B, co-immunoprecipitation of MT1/5-HT2C and MT2/5-HT2C heteromers. Lysates from HEK293T cells expressing the indicated receptors were immunoprecipitated (IP) with antibodies recognizing Myc and FLAG epitopes, and the presence of co-precipitated 5-HT2C-YFP was detected with antibodies against GFP (lower Western blot (WB)). Expression of fusion proteins in lysates was assessed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies (upper Western blots). Data are representative of three experiments. C, BRET donor saturation curves were determined by co-transfecting a fixed amount of 5-HT2C-Rluc in the presence of increasing amounts of the indicated YFP fusion proteins in HEK293 cells. Curves were normalized to BRETmax values. The saturation curves were obtained from three independent experiments performed in triplicates. D, immunofluorescence staining of permeabilized HeLa cells showing localization of 3xHA-5-HT2C (FITC) and Myc-MT2 (TRITC) expressed alone (upper and middle panels, respectively) or together (lower panels) (scale bar, 17 μm). Data are representative of three experiments. E, immunoprecipitation of melatonin receptors with 5-HT2C receptors in pork choroid plexus; 125I-labeled melatonin receptors were immunoprecipitated from solubilized membranes by anti-5-HT2C antibodies (Ab) or control (Ctrl) rabbit sera (pool of five preimmune rabbit sera). Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of three independent experiments (*, p < 0.05). Representative results are shown for A, C, and D; similar results were obtained in two additional experiments.

Melatonin but Not 5-HT Activates the Gi/cAMP Pathway through MT2/5-HT2c Heteromers

HEK293 cells expressing equivalent and physiologically relevant levels of MT2 and 5-HT2C (20–30 fmol each/mg of protein) either alone or together were treated with forskolin and increasing concentrations of melatonin followed by determination of cAMP levels. Melatonin decreased cAMP levels in cells expressing MT2 alone as expected and in cells co-expressing MT2 and 5-HT2C with the same efficiency (EC50 = 0.76 ± 0.46 versus 0.76 ± 0.39 nm, respectively) and potency (30% reduction) (Fig. 2A and Table 1). Melatonin was without effect in cells expressing 5-HT2C alone. Stimulation with up to 10 μm 5-HT did not modify cAMP levels in any of the three cell types (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that activation of the MT2 protomer of the MT2/5-HT2C heteromer activates the Gi/cAMP pathway but that activation of the 5-HT2C protomer is unable to transactivate this pathway.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of melatonin- and 5-HT-promoted activation of MT2/5-HT2C heteromers on the Gi/cAMP pathway. HEK293 cells expressing 5-HT2C (▿), MT2 (●), or 5-HT2C and MT2 (○) receptors were either treated with 2 μm forskolin (Fsk) and increasing concentrations of melatonin (MLT) (A) or increasing concentrations of 5-HT (B). Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicates.

TABLE 1.

Compared potencies and properties of melatonin receptor ligands on two signaling pathways in cells expressing MT2 or MT2 and 5-HT2C receptors

The Ki values of MTR antagonists are derived from data shown in Fig. 6 and are defined as Ki = IC50/1 + (S/X) where S and X represent the agonist concentration and EC50, respectively. ND, not determined.

| EC50 ± S.E. |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition of cAMP production |

Stimulation of inositol phosphate production |

|||

| MT2 | MT2/5-HT2C | MT2 | MT2/5-HT2C | |

| nm | ||||

| MTR agonists | ||||

| MLT | 0.76 ± 0.46 | 0.76 ± 0.39 | No effect | 69 ± 20 |

| Agomelatine | 0.29 ± 0.16 | 0.89 ± 0.35 | No effect | Antagonist |

| MTR antagonists | ||||

| Luzindole | Antagonist (Ki = 1.12 ± 0.48 nm) | Antagonist (Ki = 7.73 ± 4.98 nm) | No effect | Full agonist (EC50 = 223 ± 97 nm) |

| 4-PPDOT | Antagonist (Ki = 0.14 ± 0.12 nm) | Antagonist (Ki = 0.04 ± 0.01 nm) | No effect | Partial agonist (EC50 = 2.5 ± 1.7 nm) |

| S20928 | Antagonist (Ki = 4.88 ± 1.5 nm) | Antagonist (Ki = 0.66 ± 0.45 nm) | No effect | Antagonist (Ki = ND) |

MT2 Potentiates 5-HT-induced Signaling by Increasing Cell Surface Expression of 5-HT2C in the MT2/5-HT2C Heteromer

We next investigated the capacity of MT2/5-HT2C heteromers to activate the Gq/PLC pathway by monitoring 5-HT-induced IP production. Stimulation of HEK293 cells expressing 5-HT2C alone resulted in the expected dose-dependent increase in IP production (Fig. 3A). This response was potentiated (∼3-fold) in cells expressing similar quantities of 5-HT2C receptors, but in the presence of MT2, the response was of similar potency (EC50 = 21 ± 11 nm (5-HT2C) versus 68 ± 25 nm (MT2/5-HT2C)). 5-HT was ineffective in cells expressing MT2 alone (Fig. 3A). Amplification of the 5-HT-induced response was Gq/11- but not Gi-dependent as determined by pretreating cells with YM254890 or pertussis toxin inhibitors, respectively (Fig. 3B). Expression of the Gβγ scavenger βARKCter had no significant effect (Fig. 3C), confirming the predominant role of Gq/11α proteins in the observed amplification. Pretreatment of cells with 5-HT2C antagonists (RS102221 and SB242084) or an inverse agonist (SB206553) completely blocked the 5-HT-induced IP production in cells expressing 5-HT2C alone and in the presence of MT2 as expected (Fig. 3D). Pretreatment with S20928, a melatonin receptor antagonist, showed no cross-reactivity on 5-HT-induced responses (Fig. 3E).

FIGURE 3.

5-HT-promoted potentiation of the Gq/PLC pathway by the MT2/5-HT2C heteromer. A, 5-HT-induced IP production was assessed in HEK293 cells expressing 5-HT2C (▿), MT2 (●), or 5-HT2C and MT2 (○) receptors. B–E, HEK293 cells expressing 5-HT2C receptors alone or together with MT2 receptors were treated with heterotrimeric G protein inhibitors (B), 5-HT2C receptor ligands (D), or the melatonin receptor ligand S20928 (E) or co-expressed with the βARKCter Gβγ scavenger (C). F, cell surface expression of 5-HT2C and MT2 receptors in cells expressing 5-HT2C in the absence and presence of MT2 receptors measured by in-cell Western experiments (*, p < 0.05; n.s., not significantly different). Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicates. Results that are statistically different compared with 5-HT alone for 5-HT2C cells (●, p < 0.05; ●●, p < 0.01) and MT2/5-HT2C cells (**, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001) are indicated.

Amplified 5-HT-induced responses in the context of the MT2/5-HT2C heteromer might be explained by increased cell surface expression of 5-HT2C receptors. In agreement with previous reports, only a minor fraction of 5-HT2C receptors (13.2 ± 1.1%) was expressed at the cell surface when expressed alone as determined by in-cell Western experiments (Fig. 3F). In cells co-expressing 5-HT2C and MT2 receptors, the fraction of cell surface-expressed 5-HT2C almost doubled (22.7 ± 3.0%), whereas the total amount of 5-HT2C receptors was not modified. The total amount and the fraction of cell surface-expressed MT2 remained constant irrespective of the presence or absence of 5-HT2C. Taken together, our results indicate that MT2 co-expression potentiates 5-HT2C receptor signaling in the MT2/5-HT2C heteromer by increasing the cell surface expression of 5-HT2C.

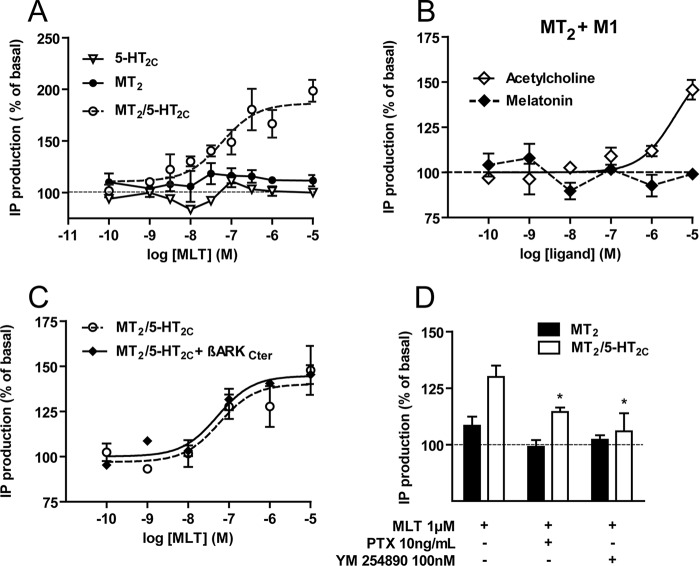

Activation of the MT2 Protomer Transactivates the PLC Pathway and Improves β-Arrestin Recruitment in the MT2/5-HT2C Heteromer

To explore the possible effect of MT2 activation in the MT2/5-HT2C heteromer on the Gq/PLC pathway, we stimulated HEK293 cells expressing MT2 and 5-HT2C either alone or together with melatonin and determined IP production. Whereas melatonin had no effect in cells expressing either receptor alone, a dose-dependent increase in IP production was observed in cells co-expressing both receptors with an EC50 of 69 ± 20 nm (Fig. 4A). To verify that melatonin-induced IP production is not due to the signaling cross-talk between MT2 and any Gq-coupled GPCR, we co-expressed MT2 with the Gq-coupled M1 muscarinic receptor, which does not form heteromers with MT2 (data not show). In these cells, melatonin did not increase IP production, indicating that melatonin-induced IP production is specific for the MT2/5-HT2C heteromer (Fig. 4B). Functional expression of M1 receptors was shown by the expected increase in IP production in the presence of acetylcholine (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Melatonin activates the Gq/PLC pathway in the MT2/5-HT2C heteromer. A, melatonin (MLT)-induced IP production was assessed in HEK293 cells expressing 5-HT2C (▿), MT2 (●), or 5-HT2C and MT2 (○) receptors. B, HEK293 cells co-expressing MT2 receptors and M1 muscarinic receptors were stimulated with melatonin or acetylcholine, and IP production was measured. The influence of the βARKCter Gβγ scavenger (C) or heterotrimeric G protein inhibitors (D) on melatonin-promoted IP production of the MT2/5-HT2C heteromer is shown. Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicates. Results that are statistically different compared with melatonin alone for MT2/5-HT2C cells (*, p < 0.05) are indicated.

Melatonin-induced IP production in cells co-expressing MT2 and 5-HT2C receptors was not affected by the expression of the Gβγ scavenger βARKCter (Fig. 4C), but it was partially and completely abrogated by pertussis toxin and YM254890 treatment, respectively (Fig. 4D). This indicates the predominant role of Gq/11α proteins, which can be assisted by the presence of Giα proteins. This result raises the intriguing possibility that melatonin binding to the MT2 protomer of the MT2/5-HT2C heteromer transactivates the 5-HT2C protomer, which then activates Gq.

To verify this hypothesis, we evaluated whether the melatonin-induced response depended on the activation state of the 5-HT2C protomer. Pretreatment of cells with 5-HT2C neutral antagonists (RS102221 and SB242084) prior to melatonin addition had no effect on melatonin-induced IP production, whereas the inverse agonist SB206553 blocked the effect (Fig. 5A). This is consistent with the notion that the melatonin-induced effect is independent of the occupation of the 5-HT2C receptor binding site but dependent on the constitutive activity of the 5-HT2C protomer.

FIGURE 5.

Transactivation of the Gq/PLC pathway by melatonin in the MT2/5-HT2C heteromer. A, melatonin (MLT)-induced IP production in the presence of 5-HT2C ligands in HEK293 cells expressing MT2 receptors alone or co-expressing 5-HT2C receptors (*, p < 0.05: melatonin versus melatonin + SB206553 on heteromers). B, 5-HT-induced IP production in cells co-expressing the 5-HT2C-S138N mutant and MT2 receptor. C, melatonin-induced transactivation of 5-HT2C wild-type and 5-HT2C-S138N mutant receptors in the presence of MT2. D, BRET donor saturation curves of HEK293 cells expressing MT2-Rluc and 5-HT2C-Rluc or 5-HT2C-S138N-Rluc. Melatonin-induced (E) and 5-HT-induced (F) recruitment of β-arrestin 2 measured by BRET in HEK293 cells expressing 5-HT2C (▿), MT2 (●), or 5-HT2C and MT2 (○) receptors is shown. Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicates. mBu, milli-BRET units.

To further verify the transactivation hypothesis, we used the 5-HT2C-S138N mutant, which does not bind 5-HT and exhibits decreased constitutive activity due to decreased coupling to Gq proteins compared with the wild-type receptor (22). The absence of 5-HT-promoted IP production was confirmed in cells expressing 5-HT2C-S138N and MT2 (Fig. 5B). When cells co-expressing this mutant and MT2 receptors were stimulated with melatonin, the anticipated reduction in amplitude and efficiency (EC50 = 550 ± 187 versus 69 ± 20 nm for MT2/5-HT2C-S138N and MT2/5-HT2C, respectively (p < 0.001)) was observed compared with 5-HT2C wild-type receptor-expressing cells (Fig. 5C). Decreased activity was not due to less efficient heteromerization with MT2 as comparable BRET50 values (2.2 ± 0.4 versus 3.5 ± 0.6 for MT2/5-HT2C and MT2/5-HT2C-S138N, respectively) were observed (Fig. 5D). The decreased response to melatonin in the presence of the 5-HT2C-S138N mutant further supports the transactivation mechanism in which the melatonin-induced conformational change in the MT2 protomer is transmitted to the 5-HT2C protomer and then further downstream to the Gq/PLC pathway.

Apart from interacting with heterotrimeric G proteins, GPCRs are also known to recruit β-arrestins. We therefore studied the ability of melatonin to activate the previously described β-arrestin 2 BRET sensor (11, 23) in cells expressing either MT2 alone or together with 5-HT2C. As seen in Fig. 5E, MT2 alone only weakly activated the BRET sensor with an EC50 of 260 ± 170 nm. In contrast, melatonin potently recruited the sensor in cells co-expressing MT2 and 5-HT2C (EC50 = 65 ± 23 nm). No effect was seen in cells expressing 5-HT2C receptors alone as expected. Stimulation with 5-HT activated the sensor in cells expressing 5-HT2C irrespective of the presence of MT2 (Fig. 5F). These results show that melatonin-induced β-arrestin recruitment to MT2 is potentiated in the MT2/5-HT2C heteromer.

Agomelatine Exhibits a Unique Functional Profile at MT2/5-HT2C Heteromers

To further explore the functional profile of MT2/5-HT2C heteromers, we studied the effect of several synthetic melatonin receptors ligands. S20928, a well know melatonin receptor antagonist (24), antagonized the melatonin-induced inhibition of cAMP levels as expected in cells expressing MT2 alone (Ki = 4.88 ± 1.50 nm) but also in cells co-expressing MT2 and 5-HT2C receptors (Ki = 0.66 ± 0.45 nm) (Table 1 and Fig. 6A). Similarly, IP production was also antagonized by S20928 under both conditions (Fig. 6B), suggesting that S20928 behaves as an antagonist of MT2/5-HT2C heteromers for both pathways. Some agonistic activity is seen at micromolar concentrations. In contrast, 4-PPDOT and luzindole, two reported antagonists of MT2 on the Gi/cAMP pathway (7, 25), showed pathway-biased properties on MT2/5-HT2C heteromers as they behaved as full antagonists on the Gi/cAMP pathway (Ki = 0.04 ± 0.01 nm and Ki = 7.73 ± 4.98 nm, respectively) but as a partial (4-PPDOT) or full (luzindole) agonist on the Gq/PLC pathway (EC50 = 2.5 ± 1.7 nm and EC50 = 223 ± 97 nm, respectively) (Fig. 6, A and C, and Table 1). Taken together, these data suggest that S20928 is an antagonist at both pathways with some partial agonistic activity at very high concentrations and that 4-PPDOT and luzindole are Gq/PLC pathway-biased ligands of MT2/5-HT2C heteromers.

FIGURE 6.

Biased ligands reveal unique functional profile of MT2/5-HT2C heteromers. A, cAMP production in HEK293 cells co-expressing MT2 and 5-HT2C receptors in the presence of 2 μm forskolin (Fsk) and different concentrations of melatonin (MLT) or 10 nm melatonin and different concentrations of 4-PPDOT, luzindole, or S20928. B, antagonistic effect of S20928 on melatonin-induced IP production in HEK293 cells expressing MT2 alone or together with 5-HT2C receptors. C, IP production in HEK293 cells co-expressing MT2 and 5-HT2C receptors in the presence of different concentrations of the indicated ligands. Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicates.

We next studied the effect of agomelatine, the antidepressant with agonistic activity at MT2 receptors and neutral antagonistic properties at 5-HT2C receptors (7, 8). In cells expressing MT2 in the absence or presence of 5-HT2C receptors, agomelatine behaved as an agonist of the Gi/cAMP pathway (EC50 = 0.29 ± 0.16 nm and EC50 = 0.89 ± 0.35 nm, respectively) (Fig. 7A and Table 1) but as an antagonist for the melatonin-induced activation of the Gq/PLC pathway (Fig. 7, B and C). Agomelatine also antagonized the 5-HT response on this pathway, which is compatible with the properties of this compound (Fig. 7D). This clearly shows that agomelatine has a distinct action profile on MT2/5-HT2C heteromers as compared with melatonin and 5-HT.

FIGURE 7.

Effect of agomelatine on the MT2/5-HT2C heteromer signaling. Effect of melatonin (MLT) and agomelatine on cAMP (A) and IP (B) production in HEK293 cells co-expressing MT2 and 5-HT2C receptors. C, effect of agomelatine on melatonin-promoted IP production in cells expressing MT2 receptors alone or together with 5-HT2C receptors. D, effect of agomelatine on 5-HT-promoted IP production in cells expressing 5-HT2C receptors alone or together with MT2 receptors. Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicates. Results that are statistically different compared with melatonin (C) or 5-HT (D) alone for MT2/5-HT2C cells (*, p < 0.05) are indicated. Fsk, forskolin.

DISCUSSION

We describe here a previously unappreciated dimension of cross-talk between melatonin and 5-HT that is mediated by heteromers of MT2 and 5-HT2C receptors. MT2/5-HT2C heteromers have unique functional properties and are formed preferentially compared with the corresponding homomers. MT1 and 5-HT2C receptors also form heteromers in transfected cells, but we focus herein on MT2/5-HT2C heteromers. Within these heteromers, melatonin is able to activate distinct cellular cascades: not only the Gi/cAMP pathway as for MT2 homomers but also the Gq/PLC pathway by transactivation of the 5-HT2C protomer. This transactivation was unidirectional and not observed for the MT2 protomer upon 5-HT stimulation. Whereas melatonin activates both pathways, other ligands have a more restricted profile using either the direct activation or transactivation mode. Interestingly, the clinically active antidepressant agomelatine shows functional properties on MT2/5-HT2C heteromers that are biased toward the Gi/cAMP pathway and thus distinct from those of melatonin- and 5-HT2C-specific antagonists.

GPCR heteromers are indeed increasingly recognized as independent pharmacological entities participating in physiological functions and drug action (4). Ligands such as agomelatine are particularly interesting in this context as they have the potential to bind to both protomers. Previous studies established that agomelatine behaves as an agonist at Gi-coupled MT1 and MT2 receptors and as a neutral antagonist at Gq/11-coupled 5-HT2C receptors (7, 8). Our data indicate that agomelatine preserves these properties in MT2/5-HT2C heteromers and behaves as a competitive antagonist on the 5-HT binding site and as an agonist on the melatonin binding site. However, not all effects of melatonin are mimicked by agomelatine because it is unable to transactivate 5-HT2C receptors. Importantly, these properties clearly distinguish agomelatine from melatonin or any other tested compound including 5-HT2C receptor antagonists.

Interestingly, the MT2/5-HT2C heteromer appears to behave in an asymmetric manner as the properties of the two protomers are differently affected by heteromerization. In the case of the 5-HT2C protomer, no modification of the signaling profile per se was observed but rather an amplification of known 5-HT-promoted responses most likely due to increased surface expression of the 5-HT2C receptor. Limited surface expression of 5-HT2C receptors is in agreement with previous studies showing a high level of constitutive internalization for this receptor (26). In the MT2 protomer, melatonin stimulation not only activates the Gi/cAMP pathway as for MT2 homomers but also transactivates the Gq/PLC pathway through the 5-HT2C protomer in a unidirectional manner (not seen upon 5-HT stimulation). Transactivation between protomers is a unique property of GPCR dimers that has been observed in a limited number of other cases such as the GABAB receptor, which is an obligatory heteromer composed of two subunits with one subunit binding the ligand and the other activating the G protein (27). Another example of this activation mode is the dopamine D2 receptors (28). Notably, the present functional characterization allowed us to identify biased ligands. Whereas luzindole and 4-PPDOT behave as agonists in the transactivation mode of the 5-HT2C protomer by the MT2 protomer, agomelatine is completely inactive in this mode but still able to fully activate the MT2 protomer.

Simultaneous activation of Gi- and Gq-dependent signaling by melatonin is a distinctive feature of MT2/5-HT2C heteromers compared with the corresponding homomers. Notably, the balance between Gi- and Gq-dependent signaling has been recently suggested to be an important parameter determining the ligand action on GPCR heteromers (29). This has been shown for mGluR2/5-HT2A heteromers, which are composed of the Gq-coupled 5-HT2A receptor and the Gi-coupled mGluR2 receptor (5) and for which the balance between Gi- and Gq-dependent signaling predicts the anti- or propsychotic activity of drugs targeting mGluR2 and 5-HT2A receptors. Antipsychotic drugs have a high Gi/Gq activation ratio regardless of which receptor they target, whereas propsychotic drugs have a low ratio. A similar balance between Gi and Gq activation can be proposed for ligands acting on MT2/5-HT2C heteromers. According to our current functional characterization, agomelatine is unique inasmuch as it possesses the highest Gi/Gq activation ratio (activation of Gi pathway and allosteric antagonistic effect on 5-HT-induced Gq pathway activation), whereas melatonin would have a more balanced Gi/Gq activation ratio (activation of both pathways), and luzindole, 4-PPDOT, and 5-HT would have a low ratio, exclusively activating the Gq pathway.

In conclusion, this present work revealed the capacity of MT2 and 5-HT2C receptors to assemble into functional heteromers. The binding and coupling properties of MT2/5-HT2C heteromers and the cellular pathway-biased ligands identified in the present study provide a solid framework for the study of the potential involvement of MT2/5-HT2C heteromers in the beneficial action of agomelatine in the treatment of major depression and generalized anxiety disorder. Targeting of GPCR heteromers might be of general importance for the increasing number of multitarget drugs developed in particular to treat psychiatric diseases (30, 31).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jean A. Boutin, Olivier Nosjean, and Francis Cogé (Servier, Croissy, France) for help during the initial phase of the project; Erika Cecon (University of Sao Paulo, Brazil) for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Fondation Recherche Médicale (Equipe FRM to R. J.), The French National Research Agency (ANR) Recherches Partenariales et Innovation Biomédicale 2012 “MED-HET-REC-2,” INSERM, CNRS, and the Who am I? laboratory of excellence ANR-11-LABX-0071 funded by the French Government through its “Investments for the Future” program operated by the ANR under Grant ANR-11-IDEX-0005-01.

- 5-HT

- serotonin

- BRET

- bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- mGluR2

- metabotropic glutamate-2 receptor

- 4-PPDOT

- 4-phenyl-2-propionamidotetralin

- Rluc

- Renilla luciferase

- TRITC

- tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate

- IP

- inositol 1-phosphate

- βARK

- β-adrenergic receptor kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Millan M. J., Marin P., Bockaert J., Mannoury la Cour C. (2008) Signaling at G-protein-coupled serotonin receptors: recent advances and future research directions. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 29, 454–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jockers R., Maurice P., Boutin J. A., Delagrange P. (2008) Melatonin receptors, heterodimerization, signal transduction and binding sites: what's new? Br. J. Pharmacol. 154, 1182–1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Prosser R. A. (1999) Melatonin inhibits in vitro serotonergic phase shifts of the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Brain Res. 818, 408–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Milligan G. (2009) G protein-coupled receptor hetero-dimerization: contribution to pharmacology and function. Br. J. Pharmacol. 158, 5–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. González-Maeso J., Ang R. L., Yuen T., Chan P., Weisstaub N. V., López-Giménez J. F., Zhou M., Okawa Y., Callado L. F., Milligan G., Gingrich J. A., Filizola M., Meana J. J., Sealfon S. C. (2008) Identification of a serotonin/glutamate receptor complex implicated in psychosis. Nature 452, 93–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pei L., Li S., Wang M., Diwan M., Anisman H., Fletcher P. J., Nobrega J. N., Liu F. (2010) Uncoupling the dopamine D1-D2 receptor complex exerts antidepressant-like effects. Nat. Med. 16, 1393–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Audinot V., Mailliet F., Lahaye-Brasseur C., Bonnaud A., Le Gall A., Amossé C., Dromaint S., Rodriguez M., Nagel N., Galizzi J. P., Malpaux B., Guillaumet G., Lesieur D., Lefoulon F., Renard P., Delagrange P., Boutin J. A. (2003) New selective ligands of human cloned melatonin MT1 and MT2 receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 367, 553–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Millan M. J., Gobert A., Lejeune F., Dekeyne A., Newman-Tancredi A., Pasteau V., Rivet J. M., Cussac D. (2003) The novel melatonin agonist agomelatine (S20098) is an antagonist at 5-hydroxytryptamine 2C receptors, blockade of which enhances the activity of frontocortical dopaminergic and adrenergic pathways. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 306, 954–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Racagni G., Riva M. A., Molteni R., Musazzi L., Calabrese F., Popoli M., Tardito D. (2011) Mode of action of agomelatine: Synergy between melatonergic and 5-HT2C receptors. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 12, 574–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Petit L., Lacroix I., de Coppet P., Strosberg A. D., Jockers R. (1999) Differential signaling of human Mel1a and Mel1b melatonin receptors through the cyclic guanosine 3′–5′-monophosphate pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 58, 633–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kamal M., Marquez M., Vauthier V., Leloire A., Froguel P., Jockers R., Couturier C. (2009) Improved donor/acceptor BRET couples for monitoring β-arrestin recruitment to G protein-coupled receptors. Biotechnol. J. 4, 1337–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berthouze M., Ayoub M., Russo O., Rivail L., Sicsic S., Fischmeister R., Berque-Bestel I., Jockers R., Lezoualc'h F. (2005) Constitutive dimerization of human serotonin 5-HT4 receptors in living cells. FEBS Lett. 579, 2973–2980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jockers R., Issad T., Zilberfarb V., de Coppet P., Marullo S., Strosberg A. D. (1998) Desensitization of the β-adrenergic response in human brown adipocytes. Endocrinology 139, 2676–2684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Savaskan E., Ayoub M. A., Ravid R., Angeloni D., Fraschini F., Meier F., Eckert A., Müller-Spahn F., Jockers R. (2005) Reduced hippocampal MT2 melatonin receptor expression in Alzheimer's disease. J. Pineal Res. 38, 10–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guillaume J. L., Daulat A. M., Maurice P., Levoye A., Migaud M., Brydon L., Malpaux B., Borg-Capra C., Jockers R. (2008) The PDZ protein mupp1 promotes Gi coupling and signaling of the Mt1 melatonin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 16762–16771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bonnefond A., Clément N., Fawcett K., Yengo L., Vaillant E., Guillaume J. L., Dechaume A., Payne F., Roussel R., Czernichow S., Hercberg S., Hadjadj S., Balkau B., Marre M., Lantieri O., Langenberg C., Bouatia-Naji N., Meta-Analysis of Glucose and Insulin-Related Traits Consortium (MAGIC), Charpentier G., Vaxillaire M., Rocheleau G., Wareham N. J., Sladek R., McCarthy M. I., Dina C., Barroso I., Jockers R., Froguel P. (2012) Rare MTNR1B variants impairing melatonin receptor 1B function contribute to type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 44, 297–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chaste P., Clement N., Mercati O., Guillaume J. L., Delorme R., Botros H. G., Pagan C., Périvier S., Scheid I., Nygren G., Anckarsäter H., Rastam M., Ståhlberg O., Gillberg C., Serrano E., Lemière N., Launay J. M., Mouren-Simeoni M. C., Leboyer M., Gillberg C., Jockers R., Bourgeron T. (2010) Identification of pathway-biased and deleterious melatonin receptor mutants in autism spectrum disorders and in the general population. PLoS One 5, e11495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mercier J. F., Salahpour A., Angers S., Breit A., Bouvier M. (2002) Quantitative assessment of β1- and β2-adrenergic receptor homo and hetero-dimerization by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 44925–44931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Couturier C., Jockers R. (2003) Activation of leptin receptor by a ligand-induced conformational change of constitutive receptor dimers. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 26604–26611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brunner P., Sözer-Topcular N., Jockers R., Ravid R., Angeloni D., Fraschini F., Eckert A., Müller-Spahn F., Savaskan E. (2006) Pineal and cortical melatonin receptors MT1 and MT2 are decreased in Alzheimer's disease. Eur. J. Histochem. 50, 311–316 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pasqualetti M., Ori M., Castagna M., Marazziti D., Cassano G. B., Nardi I. (1999) Distribution and cellular localization of the serotonin type 2C receptor messenger RNA in human brain. Neuroscience 92, 601–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Herrick-Davis K., Grinde E., Harrigan T. J., Mazurkiewicz J. E. (2005) Inhibition of serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine 2c receptor function through heterodimerization: receptor dimers bind two molecules of ligand and one G-protein. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 40144–40151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Charest P. G., Terrillon S., Bouvier M. (2005) Monitoring agonist-promoted conformational changes of β-arrestin in living cells by intramolecular BRET. EMBO Rep. 6, 334–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ying S. W., Rusak B., Delagrange P., Mocaer E., Renard P., Guardiola-Lemaitre B. (1996) Melatonin analogues as agonists and antagonists in the circadian system and other brain areas. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 296, 33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. MacKenzie R. S., Melan M. A., Passey D. K., Witt-Enderby P. A. (2002) Dual coupling of MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors to cyclic AMP and phosphoinositide signal transduction cascades and their regulation following melatonin exposure. Biochem. Pharmacol. 63, 587–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marion S., Weiner D. M., Caron M. G. (2004) RNA editing induces variation in desensitization and trafficking of 5-hydroxytryptamine 2c receptor isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 2945–2954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Galvez T., Duthey B., Kniazeff J., Blahos J., Rovelli G., Bettler B., Prézeau L., Pin J. P. (2001) Allosteric interactions between GB1 and GB2 subunits are required for optimal GABAB receptor function. EMBO J. 20, 2152–2159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Han Y., Moreira I. S., Urizar E., Weinstein H., Javitch J. A. (2009) Allosteric communication between protomers of dopamine class A GPCR dimers modulates activation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 688–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fribourg M., Moreno J. L., Holloway T., Provasi D., Baki L., Mahajan R., Park G., Adney S. K., Hatcher C., Eltit J. M., Ruta J. D., Albizu L., Li Z., Umali A., Shim J., Fabiato A., MacKerell A. D., Jr., Brezina V., Sealfon S. C., Filizola M., González-Maeso J., Logothetis D. E. (2011) Decoding the signaling of a GPCR heteromeric complex reveals a unifying mechanism of action of antipsychotic drugs. Cell 147, 1011–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Millan M. J. (2006) Multi-target strategies for the improved treatment of depressive states: conceptual foundations and neuronal substrates, drug discovery and therapeutic application. Pharmacol. Ther. 110, 135–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wong E. H., Tarazi F. I., Shahid M. (2010) The effectiveness of multi-target agents in schizophrenia and mood disorders: relevance of receptor signature to clinical action. Pharmacol. Ther. 126, 173–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]