Abstract

The pathogenesis of inhibitory antibodies has been the focus of major scientific interest over the last decades, and several studies on underlying immune mechanisms and risk factors for formation of these antibodies have been performed with the aim of improving the ability to both predict and prevent their appearance. It seems clear that the decisive factors for the immune response to the deficient factor are multiple and involve components of both a constitutional and therapy-related nature. A scientific concern and obstacle for research in the area of hemophilia is the relatively small cohorts available for studies and the resulting risk of confounded and biased results. Careful interpretation of data is recommended to avoid treatment decisions based on a weak scientific platform. This review will summarize current concepts of the underlying immunological mechanisms and risk factors for development of inhibitory antibodies in patients with hemophilia A and discuss how these findings may be interpreted and influence our clinical management of patients.

Introduction

Understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms leading to the development of inhibitory anti-factor (F)VIII antibodies in patients with hemophilia A has improved considerably over the last 2 decades. It is clear that the process is multifactorial and involves cells, cytokines, and other immune regulatory molecules, the level and action of which are both genetically and nongenetically defined. Despite improvements in understanding, we remain unable to fully predict the immune response to the deficient factor and inhibitor risk at the onset of replacement therapy. There are several ongoing efforts aiming to achieve more accurate methods for prediction and others to develop nonimmunogenic hemostatic options, but these remain opportunities for the future. Findings continue to emerge regarding risk factors and potential immune mechanisms of significance for the outcome, but until new results have been sufficiently confirmed through replication and the mechanisms of action in humans better defined, the chances of withholding a beneficial treatment or administering one associated with an adverse outcome are increased. Efficacy and safety should be the guiding principles for all treaters in the environment of cost constraints in which they act. This review will summarize current data-based findings and interpretations of how and why inhibitory antibodies develop in patients with hemophilia A and explore how the findings may or may not influence our daily practice.

Immune response to FVIII

The initiation of an immune response and formation of high-affinity polyclonal antibodies toward FVIII requires endocytosis of the infused molecule by antigen presenting cells (APCs), eg, dendritic cells, macrophages, and/or B cells, processing intracellularly in the endosomes, and presentation of antigen-derived peptides via the HLA class II molecules on the cell surface to the CD4+ T cells. In previously untreated patients, ie, patients never exposed to the deficient factor, the immune response presumably takes place by dendritic cell pathways, whereas among primed patients with an established immune response, the B cells seem to be the key APCs. Differing endocytic receptors leading to removal and degradation of FVIII have been described, but thus far, only the mannose-specific receptors have been found to process FVIII and present the digested peptides to the T cells in a manner that promotes the immune response.1 However, in recent studies, it has been shown that blockage of the mannose receptors by mannan does not prevent FVIII uptake by dendritic cells, suggesting that additional, as yet unidentified, endocytic receptors are of clinical significance.2,3 These findings are supported by the inhibitory effect on endocytosis by the monoclonal antibody KM33 that targets an epitope in the FVIII C1 domain.3 The potential role of the von Willebrand factor (VWF) as an immunoprotective chaperone for FVIII is not clear, but it may act by antigenic competition and/or by reducing endocytosis of the FVIII molecule in a dose-dependent manner, thereby preventing activation of immune effectors.2,4 The importance of cross-talk between APC and CD4+ T cells has been shown in animal models using antibodies toward costimulatory cell surface molecules interfering with the binding to the CD40 ligand, CD80/86, and CTLA4.5-10 In addition, for the CD4+ T cells to become activated and acquire the capacity to stimulate antigen-specific B-cell differentiation into antibody-secreting plasma cells and/or memory B cells, additional triggers or alert signals are often required.11 These signals—often termed danger signals—can arise from different sources, but will mainly be released by cell death, tissue damage, stress, and systemic inflammatory responses, eg, interleukins (ILs), heat shock proteins, adenosine triphosphate, reactive oxygen species, and growth factors.12 Whether a T cell-independent immune response toward FVIII is evoked into producing FVIII-specific antibodies is not completely clear, but this could potentially be of relevance for the formation of nonneutralizing antibodies and/or low-affinity antibodies.13

The neutralizing antibodies are mainly of the immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 and IgG4 subtypes and the epitopes recognized are located on both the light and heavy chains of FVIII with a preference for the A2 and C2 domains,14 although several epitopes of both neutralizing and non-neutralizing types located outside these, some in the B domain, have also been described.15,16 The main mechanism by which the antibodies neutralize the factor is by steric hindrance, but the formation of immune complexes and subsequent enhanced catabolism as well as hydrolysis have also been suggested.17 Regarding nonneutralizing antibodies, it remains debated as to whether these antibodies, or at least any immune response they provoke, are of clinical significance and should be considered as well.18-20

The importance of T-regulatory cells (Tregs) in the process of antibody formation has been established, and to date, different subsets of cells with suppressor activities have been defined, eg, CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells, IL-10-producing Tr1 cells, transforming growth factor-β-producing Th3 cells, and CD8+ Treg cells.21 Among these subsets, the CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells have received the most attention. They originate during thymic T-cell development and are also referred to as natural Tregs. They may also be induced in the periphery from conventional T cells. Treg activation occurs through antigen-specific binding to T-cell receptors, but the suppression per se appears to be a more nonspecific event, which may add somewhat to the complexity of inhibitor formation and the difficulty in finding consistent associations in relatively small hemophilia cohort studies of inhibitor formation. The action of Tregs is multifactorial and includes direct cell contact-dependent mechanisms involving APCs and/or effector T cells, as well as cytokine-mediated suppression of proliferation and differentiation. Tregs may also promote secretion of suppressive factors by dendritic cells. Interestingly, not least for the subject of inhibitor formation in hemophilia, heme oxigenase-1, which catalyzes the formation of carbon monoxide through heme degradation, has also been linked to Treg function.22 Thus, the recent report of associations between inhibitor development and polymorphisms in the HMOX-1 gene is of interest and requires further follow-up.23

Tregs have also been implicated in the process of inducing tolerance in patients with an established memory using immune tolerance induction (ITI) therapy. Here, frequent exposure to the deficient factor in the absence of systemic inflammation may induce Tregs with a subsequent lack of T-helper cells, preventing B-cell differentiation and promoting tolerance through B-cell anergy and/or deletion.24 In this process, dosing has been implicated as a crucial factor in that high doses in a murine model of hemophilia A irreversibly inhibited the memory B cells via an indirect effect on both APCs and T cells.25 This may explain the benefits of high-dose immune tolerance protocols, but because only 1 randomized ITI study has been completed in humans and that study focused on “good-risk” patients, the extent to which these in vitro findings are applicable is not clear. Whether the dose as such will be important for the outcome of ITI in other patient groups remain to be studied. Other findings, including those from the original Malmö ITI protocol,26,27 are the suggested effect of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) on Treg expansion and function, as well as the activation of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells by major histocompatibility complex class II epitopes in the Fc fragment of IgG.28,29 These results should be further evaluated to better understand the potential benefit of including IVIG in ITI protocols.

Risk factors for inhibitor risk

Causative FVIII mutation

A threefold higher risk for siblings to develop an inhibitor, if an inhibitor has previously been identified within the family, has been described.30,31 These findings suggest a genetic predisposition for development of inhibitory antibodies. Whether this is also true for nonneutralizing antibodies is not yet clear, but logically follows. Interestingly, recent preliminary findings also suggest that the epitopes of these antibodies may be inherited and shared constitutionally within families (Christoph Königs, personal communication, July 1, 2014). These are results that have potential therapeutic implications.

The importance of the causative mutation is well established, and in a recent meta-analysis by Gouw et al, the inhibitor risks in patients with large deletions (odds ratio = 3.6; 95% confidence interval, 2.3-5.7) and nonsense mutations (odds ratio = 1.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-1.8) were confirmed to be higher than those in patients with intron 22 inversions.32 A high frequency of inhibitors has also been reported for other mutations, eg, small deletions/insertions outside A-runs, splice-site mutations at conserved nucleotides at position + or –1 or 2 nucleotides, and certain missense mutations (Arg593 > Cys, Tyr2105 > Cys, Arg2150 > His, Arg2163 > His, Trp2229 > Cys, and Pro2300 > Leu).33 The determinants of inhibitor formation are far more complex and individually variable than can be described in a meta-analysis. It is surprising that not all patients without circulating endogenous antigen (cross-reacting material negative [crm−]) form antibodies when exposed to the deficient factor; only some do! The role of the major histocompatibility complex class II alleles is implicated and will be discussed below, but it is certainly the case that as yet unidentified mechanisms will contribute to efficient downregulation of the immune response in the majority of crm− patients. It is even the case that discordant inhibitor histories within families with large deletions have been described, which is further proof of the complexity of the system.34 Therefore, it is worth emphasizing that despite odds ratios of the magnitude of 2 to 3 for various risk factors, including the most scrutinized risk factor of all, ie, the underlying mutation, the predictive value of a specific factor is rather weak, and the treater should not, at this point, make therapeutic decisions based on a perceived inhibitor risk, unless these are justified by other circumstances. In crm+ patients, such as those with a mild form of the disease carrying the Arg593 > Cys mutation, the association with the underlying mutation appears clearer, and whenever possible, the use of replacement therapy should be avoided and other hemostatic agents such as desmopressin should be used instead.35,36

HLA class II

A point mutation may be associated with inhibitor risk based on the induced conformational changes and/or impaired function. There will also be a close correlation to the HLA class II alleles in each subject. It has been difficult to consistently define risk alleles within the HLA system, presumably due to promiscuity and heterogeneity and the peptides they bind. This does not diminish its importance and critical role. Recently, using computer-based in silico methods, the FVIII-specific T-cell tolerance and inhibitor risk was suggested to correlate with the binding affinity of the oligopeptides to the HLA alleles in subjects with point mutations.37 Computerized models for determining the role of the HLA class II alleles have become frequently used over the years, recently in the context of FVIII polymorphisms and inhibitor risk in patients with the H3/H4 haplotypes.38 Indeed, this approach may be a useful tool for further elucidating the complex immune response, but more data and relationship to the clinical setting are required to confirm the findings.

The types of FVIII mutations that confer high risk are under debate, and the HLA class II system may be one of the keys to defining this group. As recently reported for the intron 22 inversion, tolerance may also be induced in patients considered to be crm− by endogenous synthesis of the deficient protein, or at least part of it.39 The factors that mitigate the discrepant outcome among patients, including sibling pairs, with this type of mutation may be determined by the number of putative T-cell epitopes in the infused molecule and the ability to form stable HLA-peptide complexes. Whether endogenous synthesis may also be relevant for tolerance induction in other cases remains to be investigated.

Immune response genes

The significant capacity of cytokines, chemokines, and other immune regulatory molecules to modify immunogenicity and clinical outcome has been reported for a variety of immune-mediated diseases, and, in some instances, therapeutic interventions targeting these molecules have significantly improved patient care. Thus far, this is not the case for hemophilia, but several polymorphic candidate genes have been suggested over the last decade. These are summarized in Table 1.40-52 Based on current understanding, it seems unlikely that a single marker of significantly greater importance than multiple others will be identified. In fact, the associations found between polymorphic genes and inhibitory antibodies have not been consistent across study cohorts, and the question, of course, is why? Presumably, the reason is multifactorial and includes differing analytical/technical approaches, study design and insufficient statistical power, the influence of nongenetic factors, and the complexity of the immune response per se. The most consistent and frequently reported polymorphic gene associated with inhibitor risk is the IL-10 gene. This was first reported in the Malmö International Brother Study, but has since been confirmed in other study cohorts and different study designs (Table 1). Polymorphisms within the promoter region of this gene are associated with modified expression levels, and because the IL-10 molecule appears to be a crucial immune mediator with mechanisms of action including modification of T-cell proliferation and cytokine production, promotion of Treg-cell proliferation and B-cell proliferation and maturation, and various effects on APCs, the potential relevance of the findings are obvious.53 An IL-10-mediated interplay between viral infections, such as HIV, and the antibody response has also been suggested, but the importance for this in patients with hemophilia requires further evaluation.43 Among the other polymorphic candidate genes reported to be associated with FVIII inhibitors are those coding for tumor necrosis factor α (TNFA) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4). These have also been replicated in different cohorts as well. Additional polymorphic markers have been reported but require further evaluation to rule out false-positive associations. In the Hemophilia Inhibitor Genetics Study (HIGS), 3 independent study cohorts were used for replication.33 The results of a subsequent evaluation of initial HIGS findings in brother pairs are of special interest for more detailed scrutiny. Among the panel of genes and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) tested, those indicating a significant association independently in the cohorts were tested in the group of 104 brother pairs discordant for inhibitor status. Despite the relatively small number of pairs, 8 SNPs (Table 1) were consistently significant, including regulators of the intracellular signaling of T-cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation. This includes, for example, IGSF2, a transmembrane glycoprotein expressed on APCs, T effector cells, and CD4+CD25+Fox3p+ cells, with an effect on T cells mediated via IL-10 production.54,55 The HIGS findings encourage the search for common pathways of immune mediators that may act together and hopefully provide potential therapeutic targets to intervene on the immune mechanisms. It is also noteworthy that the immune regulatory genes demonstrate the highest degree of recombination, causing a substantial degree of variability among patients, which, together with the variation of HLA class II alleles profiles, may explain the varying frequency of inhibitor development reported among ethnic groups.

Table 1.

Summary of polymorphic immune response genes reported in the literature to be associated with increased (risk) or decreased (protective) frequency of inhibitors in the literature

| Gene | Type of polymorphism | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interleukin 10 (IL 10) | Microsatellite | Risk | 40 |

| SNP | Risk | 41 | |

| SNP | Risk | 42 | |

| SNP Haplotype | Risk | 43 | |

| SNP Haplotype | Risk | 44 | |

| SNP Haplotype | Risk | 45 | |

| SNP Haplotype | Risk | 46 | |

| Interleukin 1α (IL-1α) | SNP Haplotype | Risk | 43 |

| Interleukin 1β (IL-1β) | SNP Haplotype | Protective | 43 |

| Interleukin 2 (IL-2) | SNP Haplotype | Protective | 43 |

| Interleukin 5 (IL-5) | SNP | Risk | 47 |

| Interleukin 12A (IL-12A) | SNP Haplotype | Risk | 43 |

| Transforming Growth Factor β | NA | Protective | 48 |

| Tumor Necrosis Factor α (TNFA) | SNP | Risk | 45 |

| SNP | Risk | 41 | |

| SNP | Risk | 49 | |

| Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte Antigen 4 (CTLA4) | SNP | Risk | 50 |

| SNP | Protective | 51 | |

| CD40/CD40L | NA | Protective | 48 |

| CD44 | SNPs (2) | Risk | 33 |

| Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase, Receptor Type, M (PTPRM) | SNP | Risk | 33 |

| Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Superfamily, Member 21 (TNFRSF21) | SNP | Risk | 33 |

| Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase 9 (MAPK9) | SNP | Risk | 33 |

| Immunoglobulin Superfamily, Member 2 (IGSF2) | SNP | Protective | 33 |

| Macrophage Scavenger Receptor 1 (MSR1) | SNP | Protective | 33 |

| Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase, Receptor Type, E (PTPRE) | SNP | Protective | 33 |

| Heme Oxygenase-1-Encoding (HMOX1) | Microsatellite | Risk | 23 |

| Fc γ Receptors 2A (FCGR2A) | SNP | Risk | 52 |

For the HIGS combined cohort study, only SNPs associated with inhibitors in the subgroup of discordant brother pairs are shown.33

Race and ethnicity

Variation in inhibitor risk among racial and ethnic groups has been a consistent finding in several studies, eg, a higher risk in those of African and Latino ancestry, underlining the importance of inherent factors of the individual.56-59 The explanation for the discrepancy remains to be elucidated. In the case of subjects of African descent, a two- to threefold higher inhibitor risk has been attributed to the FVIII haplotype and a mismatch between the endogenous FVIII molecule and the molecule in the factor concentrate used for treatment.57 However, there are several other genetic markers with a significant degree of ethnic variability, including both HLA class II alleles and the polymorphic profile of immune regulatory genes, all of which may contribute to the outcome.38,58

Nongenetic factors

Several potential nongenetic risk factors have been suggested over the years.60 Interestingly, some factors initially thought to enhance inhibitor risk, such as young age at start of replacement therapy, have since either been ruled out or shown to potentially be associated with the opposite effect. This underscores the importance of careful evaluation of new literature reports and the need for confirmation of results from other cohorts and clinical settings before making significant revisions in the clinical management of patients—revisions that may in fact jeopardize outcome in other respects. In a survey performed within a European network of large hemophilia comprehensive care centers, the disparate opinions of experienced colleagues with respect to those factors that moderated risk was obvious. Both the views on importance of different factors, as well as how they influenced the clinical management of patients, varied widely.60 It is hoped that some of the ongoing studies within the field will be able to shed more light and either confirm, or rule out, a number of these factors.

Nongenetic risk factors include those related to treatment, such as the type of product, dosing regimen, switching products, and mode of administration, and those related to immune system challenges and inflammatory processes providing alert signals to the immune system. Apart from outbreaks in the early 1990s due to a modified and neo-immunogenic factor molecule,61,62 none of the treatment-related factors have been confirmed, in a rigorously scientific manner, to influence inhibitor risk. This includes the long-standing debate regarding factor concentrate-related immunogenicity and whether some of the currently available products are associated with more or less risk for inhibitors than others.63-65 This is not to say that all FVIII molecules in the concentrates act alike or evoke exactly the same immunological response, but no clinical decisions should be made on the data available today to minimize risk. Rather, other aims and conditions should be the deciding factors. The ongoing Survey of Inhibitors in Plasma-Product Exposed Toddlers study may add to the knowledge base, but for now and the coming years, it is unlikely there will be sufficient evidence with which to base a decision, because all studies will be hampered by heterogeneity among patients, small cohort sizes, and lack of statistical power, as well as the inability to adequately adjust for crucial confounding factors. Instead, the reason why treatment has been provided will be of major importance. It is possible that in an inflammatory setting in the presence of alert signals for the immune system, the amount of exposed antigen may be of relevance to risk. Thus, to the degree possible from a medical and safety perspective, treatment should be minimized—in terms of time and amount—to avoid what has been termed peak treatment moments.66,67 This refers to infusion of factor concentrates for consecutive days for treatment of severe bleeds and/or to cover for surgical procedures. In the Concerted Action on Neutralizing Antibodies in severe hemophilia A study, peak treatment moments for ≥5 days as the initial treatment were associated with an adjusted relative risk of 2 to 3 for inhibitor development.66 It is logical to assume that replacement therapy in association with immunizations and severe infections should also confer a higher risk of inhibitor formation due to coexistence of alert or danger signals. However, this has not been observed, perhaps due to study design and/or lack of statistical power, but whenever possible, these procedures and conditions should be provided and treated in the absence of a high antigen load. Starting treatment at a young age by providing the antigen prophylactically, once weekly in relatively low doses in the absence of any alert signals, has been suggested to reduce the inhibitor risk.68 However, the findings have not been reproducible in other cohorts, and a recent study designed to address this potentially beneficial effect of prophylaxis was terminated in advance due to the relatively high frequency of inhibitors.69 The Research of Determinants of Inhibitor Development (RODIN) study also could not replicate the initial Concerted Action on Neutralizing Antibodies in severe hemophilia A study findings of a protective effect of use of prophylaxis for the first 20 exposures, ie, the time period during which most inhibitors develop.70 Prophylaxis remains the gold standard of treatment and should be used whenever possible, but the tolerogenic benefits and the potential effects of dosing and treatment intervals remain to be settled.

Avoidance and concluding remarks

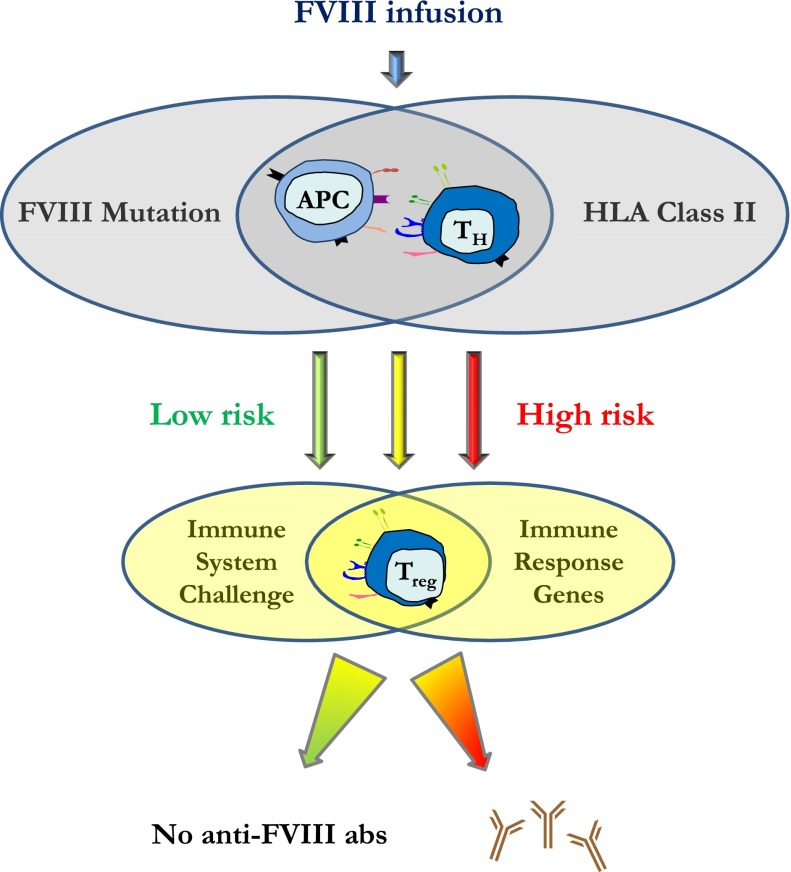

Therefore, to sum up: to what extent does our knowledge of the pathogenesis and risk factors for development of inhibitors to FVIII permit us to predict and prevent them from occurring? First, once the immune response has been established and memory cells have been formed, it will likely not be possible to identify single mechanisms and/or factors to target to prevent the formation of inhibitors and/or to induce tolerance. Instead, to effectively prevent the antibodies from occurring, it will be crucial to prevent the initial activation of the naïve cells at a young age, perhaps even in utero. Once established, several immune mechanisms and pathways will have the capacity to modify the risk on an individual basis. Subgroups of patients may be defined: the high-risk patients with crm− antigen status and HLA class II alleles forming stable peptide complexes with numerous T-cell epitopes; the low-risk population with crm+ status, a point mutation associated with minor effects on the secondary and tertiary FVIII structure, and HLA class II profiles not able to present the mutated amino acid(s) to the T cells (Figure 1). An intermediate subgroup of patients will be the most challenging to define. In these subjects, inflammatory markers released in association with immune system challenges and partly genetically defined will probably be discriminative. As a general rule, replacement therapy in association with a systemic inflammatory response should be avoided if possible, feasible, and medically defensible. Instead, despite the lack of confirmatory data on inhibitor prevention, when indicated, such as for patients with more severe forms of hemophilia, regular replacement therapy provided at young age to prevent bleeding events in the presence of a minimum of coexisting inflammatory markers is preferable, because this treatment mode, besides being recommended for protection against harmful bleeds, still may be tolerogenic in a subset of patients. If prophylaxis is not possible using peripheral veins, then the placement of central lines can be considered; even though the insertion of such devices entails surgery, there is no substantive evidence to show that these procedures increase inhibitor risk. Given risk of infection and other adverse events, a peripheral route of administration should, however, if possible, be the first option. Regarding FVIII dosing, dose interval, and the proposed preventive effect of low-dose prophylaxis at young age, there may be an advantage for high-risk patients if treatment could be started with low doses prophylactically, but there are no confirmed clinical data to support this approach and no data suggesting that an interval of once weekly is preferable to more frequent infusions, provided the factor is not provided in an inflammatory setting. Regarding type of concentrate and inhibitor risk, there is no current information to suggest a more favorable outcome for one product over another. This includes the choice of product used to eradicate the immune response once established.71 However, due to the potential modulation of exposed epitopes and idiotypic competitive binding by VWF binding to FVIII, it is not possible to rule out a potential beneficial effect among some patients. Therefore, a VWF-containing FVIII product may be indicated for use in patients failing initial ITI attempts. Immunizations should be provided to all patients according to the same schedule as healthy subjects but, whenever possible, preferentially administered subcutaneously to avoid combined infusion of the deficient factor in a setting of alert signals.

Figure 1.

Schematic model of anti-FVIII inhibitor formation. The causative FVIII mutation and HLA class II will be the main contributors to the risk of development of antibodies; from very low risk (green) unlikely to experience any antibodies with commercially available FVIII concentrates to very high risk (red). The final immune response and outcome will then be fine-tuned by T-regulatory cells and a variety of immune regulatory molecules, the activity of which will be defined genetically by therapy-related factors and immune system challenges.

Finally, a patient-specific discriminative predictive score for use before the onset of treatment would be of great value, as more individualized treatment options will presumably be available in the future. Is this possible? Animal models will certainly contribute to reaching this goal, but unlikely be able to address the complex mechanisms in humans. Instead, these models must be derived from studies of patient cohorts with a minimum of variability in constitutional, environmental, and treatment-related factors. Brothers discordant for inhibitor status may, in this setting, be of special value—perhaps as good as it gets. International collaborative studies of this design should be encouraged. If then, an improved prediction can be made, how may the treatment be individualized? First, hemostatic agents other than the deficient factor may be available and used without introducing the problem of immunogenicity. In addition, the coadministration of the deficient factor and immunosuppressive drugs may be a way forward, and, in fact, the coadministration of FVIII and dexamethasone was recently reported to reduce anti-FVIII antibody development in a mouse model of hemophilia A.72 Interestingly, there are other single gene disorders with a complete loss of protein expression analogous to severe hemophilia A, such as congenital inborn errors of metabolism, in which this concept appears to be a successful method for avoiding antibody formation. Some of the disorders can be treated with recombinant human substitutes, and, as with hemophilia, this replacement is often compromised by inactivating antibodies, especially in crm− subjects. In both animal and human models, the use of immunosuppressive agents, eg, methotrexate and/or rituximab, with or without IVIG, were found to induce immune tolerance to the deficient enzyme,73,74 and a similar strategy may be relevant for patients with hemophilia and evaluation in well-designed studies should be considered.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Sharyne Donfield for skilled technical support, expertise, and valuable comments on the manuscript.

Authorship

Contribution: J.A. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.A. has received research grants from Baxter, Octapharma, and Bayer and participated in advisory boards for CSL Behring, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, Baxter, and Bayer.

Correspondence: Jan Astermark, Department for Hematology and Vascular Medicine, Center for Thrombosis and Haemostasis, Skåne University Hospital Malmö, SE-205 02 Malmö, Sweden; e-mail: jan.astermark@med.lu.se.

References

- 1.Dasgupta S, Navarrete AM, Bayry J, et al. A role for exposed mannosylations in presentation of human therapeutic self-proteins to CD4+ T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(21):8965–8970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702120104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delignat S, Repessé Y, Navarrete AM, et al. Immunoprotective effect of von Willebrand factor towards therapeutic factor VIII in experimental haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2012;18(2):248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herczenik E, van Haren SD, Wroblewska A, et al. Uptake of blood coagulation factor VIII by dendritic cells is mediated via its C1 domain. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;129(2):501-509. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Dasgupta S, Repessé Y, Bayry J, et al. VWF protects FVIII from endocytosis by dendritic cells and subsequent presentation to immune effectors. Blood. 2007;109(2):610–612. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-022756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian J, Collins M, Sharpe AH, Hoyer LW. Prevention and treatment of factor VIII inhibitors in murine hemophilia A. Blood. 2000;95(4):1324–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reipert BM, Sasgary M, Ahmad RU, Auer W, Turecek PL, Schwarz HP. Blockade of CD40/CD40 ligand interactions prevents induction of factor VIII inhibitors in hemophilic mice but does not induce lasting immune tolerance. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86(6):1345–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossi G, Sarkar J, Scandella D. Long-term induction of immune tolerance after blockade of CD40-CD40L interaction in a mouse model of hemophilia A. Blood. 2001;97(9):2750–2757. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.9.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hausl C, Ahmad RU, Schwarz HP, et al. Preventing restimulation of memory B cells in hemophilia A: a potential new strategy for the treatment of antibody-dependent immune disorders. Blood. 2004;104(1):115–122. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miao CH, Ye P, Thompson AR, Rawlings DJ, Ochs HD. Immunomodulation of transgene responses following naked DNA transfer of human factor VIII into hemophilia A mice. Blood. 2006;108(1):19–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng B, Ye P, Blazar BR, et al. Transient blockade of the inducible costimulator pathway generates long-term tolerance to factor VIII after nonviral gene transfer into hemophilia A mice. Blood. 2008;112(5):1662–1672. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-128413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matzinger P. The danger model: a renewed sense of self. Science. 2002;296(5566):301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.1071059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pradeu T, Cooper EL. The danger theory: 20 years later. Front Immunol. 2012;3:287. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pordes AG, Baumgartner CK, Allacher P, et al. T cell-independent restimulation of FVIII-specific murine memory B cells is facilitated by dendritic cells together with toll-like receptor 7 agonist. Blood. 2011;118(11):3154–3162. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-336198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whelan SF, Hofbauer CJ, Horling FM, et al. Distinct characteristics of antibody responses against factor VIII in healthy individuals and in different cohorts of hemophilia A patients. Blood. 2013;121(6):1039–1048. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-444877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmer DS, Dudani AK, Drouin J, Ganz PR. Identification of novel factor VIII inhibitor epitopes using synthetic peptide arrays. Vox Sang. 1997;72(3):148–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.1997.7230148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang CC, Shen MC, Chen JY, Hung MH, Hsu TC, Lin SW. Epitope mapping of factor VIII inhibitor antibodies of Chinese origin. Br J Haematol. 2001;113(4):915–924. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacroix-Desmazes S, Bayry J, Misra N, et al. The prevalence of proteolytic antibodies against factor VIII in hemophilia A. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(9):662–667. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavigne-Lissalde G, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Wootla B, et al. Molecular characterization of human B domain-specific anti-factor VIII monoclonal antibodies generated in transgenic mice. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98(1):138–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klintman J, Hillarp A, Berntorp E, Astermark J. Long-term anti-FVIII antibody response in Bethesda-negative haemophilia A patients receiving continuous replacement therapy. Br J Haematol. 2013;163(3):385–392. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butenas S, Krudysz-Amblo J, Rivard GE, G Mann K. Product-dependent anti-factor VIII antibodies. Haemophilia. 2013;19(4):619–625. doi: 10.1111/hae.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao O, Loduca PA, Herzog RW. Role of regulatory T cells in tolerance to coagulation factors. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(Suppl 1):88–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang Q, Bluestone JA. The Foxp3+ regulatory T cell: a jack of all trades, master of regulation. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(3):239–244. doi: 10.1038/ni1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Repessé Y, Peyron I, Dimitrov JD, et al. ABIRISK consortium. Development of inhibitory antibodies to therapeutic factor VIII in severe hemophilia A is associated with microsatellite polymorphisms in the HMOX1 promoter. Haematologica. 2013;98(10):1650–1655. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.084665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reipert BM, van Helden PM, Schwarz HP, Hausl C. Mechanisms of action of immune tolerance induction against factor VIII in patients with congenital haemophilia A and factor VIII inhibitors. Br J Haematol. 2007;136(1):12–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hausl C, Ahmad RU, Sasgary M, et al. High-dose factor VIII inhibits factor VIII-specific memory B cells in hemophilia A with factor VIII inhibitors. Blood. 2005;106(10):3415–3422. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berntorp E, Astermark J, Carlborg E. Immune tolerance induction and the treatment of hemophilia. Malmö protocol update. Haematologica. 2000;85(10 Suppl):48–50, discussion 50-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlborg E, Astermark J, Lethagen S, Ljung R, Berntorp E. The Malmö model for immune tolerance induction: impact of previous treatment on outcome. Haemophilia. 2000;6(6):639–642. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2000.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ephrem A, Chamat S, Miquel C, et al. Expansion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by intravenous immunoglobulin: a critical factor in controlling experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Blood. 2008;111(2):715–722. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-079947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Groot AS, Moise L, McMurry JA, et al. Activation of natural regulatory T cells by IgG Fc-derived peptide “Tregitopes”. Blood. 2008;112(8):3303–3311. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-138073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Astermark J, Berntorp E, White GC, Kroner BL MIBS Study Group. The Malmö International Brother Study (MIBS): further support for genetic predisposition to inhibitor development in hemophilia patients. Haemophilia. 2001;7(3):267–272. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2001.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gill JC. The role of genetics in inhibitor formation. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82(2):500–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gouw SC, van den Berg HM, Oldenburg J, et al. F8 gene mutation type and inhibitor development in patients with severe hemophilia A: systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2012;119(12):2922–2934. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Astermark J, Donfield SM, Gomperts ED, et al. Hemophilia Inhibitor Genetics Study (HIGS) Combined Cohort. The polygenic nature of inhibitors in hemophilia A: results from the Hemophilia Inhibitor Genetics Study (HIGS) Combined Cohort. Blood. 2013;121(8):1446–1454. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-434803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Astermark J, Oldenburg J, Escobar M, White GC, II, Berntorp E Malmö International Brother Study study group. The Malmö International Brother Study (MIBS). Genetic defects and inhibitor development in siblings with severe hemophilia A. Haematologica. 2005;90(7):924–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eckhardt CL, Menke LA, van Ommen CH, et al. Intensive peri-operative use of factor VIII and the Arg593—>Cys mutation are risk factors for inhibitor development in mild/moderate hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(6):930–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eckhardt CL, van Velzen AS, Peters M, et al. INSIGHT Study Group. Factor VIII gene (F8) mutation and risk of inhibitor development in nonsevere hemophilia A. Blood. 2013;122(11):1954–1962. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-483263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pashov AD, Calvez T, Gilardin L, et al. In silico calculated affinity of FVIII-derived peptides for HLA class II alleles predicts inhibitor development in haemophilia A patients with missense mutations in the F8 gene. Haemophilia. 2014;20(2):176–184. doi: 10.1111/hae.12276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pandey GS, Yanover C, Howard TE, Sauna ZE. Polymorphisms in the F8 gene and MHC-II variants as risk factors for the development of inhibitory anti-factor VIII antibodies during the treatment of hemophilia a: a computational assessment. PLOS Comput Biol. 2013;9(5):e1003066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pandey GS, Yanover C, Miller-Jenkins LM, et al. PATH (Personalized Alternative Therapies for Hemophilia) Study Investigators. Endogenous factor VIII synthesis from the intron 22-inverted F8 locus may modulate the immunogenicity of replacement therapy for hemophilia A. Nat Med. 2013;19(10):1318–1324. doi: 10.1038/nm.3270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Astermark J, Oldenburg J, Pavlova A, Berntorp E, Lefvert AK MIBS Study Group. Polymorphisms in the IL10 but not in the IL1beta and IL4 genes are associated with inhibitor development in patients with hemophilia A. Blood. 2006;107(8):3167–3172. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pavlova A, Delev D, Lacroix-Desmazes S, et al. Impact of polymorphisms of the major histocompatibility complex class II, interleukin-10, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 genes on inhibitor development in severe hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(12):2006–2015. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaves D, Belisário A, Castro G, Santoro M, Rodrigues C. Analysis of cytokine genes polymorphism as markers for inhibitor development in haemophilia A. Int J Immunogenet. 2010;37(2):79–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2009.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lozier JN, Rosenberg PS, Goedert JJ, Menashe I. A case-control study reveals immunoregulatory gene haplotypes that influence inhibitor risk in severe haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2011;17(4):641–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu Y, Ding Q, Dai J, Wang H, Wang X. Impact of polymorphisms in genes involved in autoimmune disease on inhibitor development in Chinese patients with haemophilia A. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(1):30–36. doi: 10.1160/TH11-06-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pinto P, Ghosh K, Shetty S. Immune regulatory gene polymorphisms as predisposing risk factors for the development of factor VIII inhibitors in Indian severe haemophilia A patients. Haemophilia. 2012;18(5):794–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2012.02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pergantou H, Varela I, Moraloglou O, et al. Impact of HLA alleles and cytokine polymorphisms on inhibitors development in children with severe haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2013;19(5):706–710. doi: 10.1111/hae.12168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fidancı ID, Zülfikar B, Kavaklı K, et al. A Polymorphism in the IL-5 Gene is Associated with Inhibitor Development in Severe Hemophilia A Patients. Turk J Haematol. 2014;31(1):17–24. doi: 10.4274/Tjh.2012.0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gaitonde P, Peng A, Straubinger RM, Bankert RB, Balu-Iyer SV. Downregulation of CD40 signal and induction of TGF-β by phosphatidylinositol mediates reduction in immunogenicity against recombinant human Factor VIII. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101(1):48–55. doi: 10.1002/jps.22746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Astermark J, Oldenburg J, Carlson J, et al. Polymorphisms in the TNFA gene and the risk of inhibitor development in patients with hemophilia A. Blood. 2006;108(12):3739–3745. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Astermark J, Wang X, Oldenburg J, Berntorp E, Lefvert AK MIBS Study Group. Polymorphisms in the CTLA-4 gene and inhibitor development in patients with severe hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(2):263–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pavlova A, Diaz-Lacava A, Zeitler H, et al. Increased frequency of the CTLA-4 49 A/G polymorphism in patients with acquired haemophilia A compared to healthy controls. Haemophilia. 2008;14(2):355–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eckhardt CL, Astermark J, Nagelkerke SQ, et al. The Fc gamma receptor IIa R131H polymorphism is associated with inhibitor development in severe hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(8):1294–1301. doi: 10.1111/jth.12631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bouloc A, Bagot M, Delaire S, Bensussan A, Boumsell L. Triggering CD101 molecule on human cutaneous dendritic cells inhibits T cell proliferation via IL-10 production. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30(11):3132–3139. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200011)30:11<3132::AID-IMMU3132>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fernandez I, Zeiser R, Karsunky H, et al. CD101 surface expression discriminates potency among murine FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179(5):2808–2814. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aledort LM, Dimichele DM. Inhibitors occur more frequently in African-American and Latino haemophiliacs. Haemophilia. 1998;4(1):68. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.1998.0146c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Viel KR, Ameri A, Abshire TC, et al. Inhibitors of factor VIII in black patients with hemophilia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1618–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa075760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schwarz J, Astermark J, Menius ED, et al. Hemophilia Inhibitor Genetics Study Combined Cohort. F8 haplotype and inhibitor risk: results from the Hemophilia Inhibitor Genetics Study (HIGS) Combined Cohort. Haemophilia. 2013;19(1):113–118. doi: 10.1111/hae.12004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carpenter SL, Michael Soucie J, Sterner S, Presley R Hemophilia Treatment Center Network (HTCN) Investigators. Increased prevalence of inhibitors in Hispanic patients with severe haemophilia A enrolled in the Universal Data Collection database. Haemophilia. 2012;18(3):e260–e265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Astermark J, Altisent C, Batorova A, et al. European Haemophilia Therapy Standardisation Board. Non-genetic risk factors and the development of inhibitors in haemophilia: a comprehensive review and consensus report. Haemophilia. 2010;16(5):747–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosendaal FR, Nieuwenhuis HK, van den Berg HM, et al. Dutch Hemophilia Study Group. A sudden increase in factor VIII inhibitor development in multitransfused hemophilia A patients in The Netherlands. Blood. 1993;81(8):2180–2186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peerlinck K, Arnout J, Gilles JG, Saint-Remy JM, Vermylen J. A higher than expected incidence of factor VIII inhibitors in multitransfused haemophilia A patients treated with an intermediate purity pasteurized factor VIII concentrate. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69(2):115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iorio A, Halimeh S, Holzhauer S, et al. Rate of inhibitor development in previously untreated hemophilia A patients treated with plasma-derived or recombinant factor VIII concentrates: a systematic review. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(6):1256–1265. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gouw SC, van der Bom JG, Ljung R, et al. PedNet and RODIN Study Group. Factor VIII products and inhibitor development in severe hemophilia A. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(3):231–239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Franchini M, Coppola A, Rocino A, et al. Italian Association of Hemophilia Centers (AICE) Working Group. Systematic review of the role of FVIII concentrates in inhibitor development in previously untreated patients with severe hemophilia a: a 2013 update. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2013;39(7):752–766. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1356715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gouw SC, van der Bom JG, Marijke van den Berg H. Treatment-related risk factors of inhibitor development in previously untreated patients with hemophilia A: the CANAL cohort study. Blood. 2007;109(11):4648–4654. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-056291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gouw SC, van den Berg HM, le Cessie S, van der Bom JG. Treatment characteristics and the risk of inhibitor development: a multicenter cohort study among previously untreated patients with severe hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(7):1383–1390. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kurnik K, Bidlingmaier C, Engl W, Chehadeh H, Reipert B, Auerswald G. New early prophylaxis regimen that avoids immunological danger signals can reduce FVIII inhibitor development. Haemophilia. 2010;16(2):256–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2009.02122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Auerswald G, Kurnik K, Blatny J, et al. The EPIC Study: a clinical trial to assess whether early low dose prophylaxis in the absence of immunological danger signals reduces inhibitor incidence in previously untreated patients (PUPs) with hemophilia A. Abstract No. 576. American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting, New Orleans 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gouw SC, van den Berg HM, Fischer K, et al. PedNet and Research of Determinants of INhibitor development (RODIN) Study Group. Intensity of factor VIII treatment and inhibitor development in children with severe hemophilia A: the RODIN study. Blood. 2013;121(20):4046–4055. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-457036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.van Velzen AS, Peters M, van der Bom JG, Fijnvandraat K. Effect of von Willebrand factor on inhibitor eradication in patients with severe haemophilia A: a systematic review. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):485–495. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moorhead P, van Velzen A, Sponagle K, et al. Co-administration of factor VIII and dexamethasone prevents anti-factor VIII antibody development in a mouse model of hemophilia A. Abstract No. (OC 56.6) International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Congress 2013, Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Messinger YH, Mendelsohn NJ, Rhead W, et al. Successful immune tolerance induction to enzyme replacement therapy in CRIM-negative infantile Pompe disease. Genet Med. 2012;14(1):135–142. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Garman RD, Munroe K, Richards SM. Methotrexate reduces antibody responses to recombinant human alpha-galactosidase A therapy in a mouse model of Fabry disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;137(3):496–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]