Abstract

Objective

To estimate the impact of HIV infection on the incidence of high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

Study Design

HIV seropositive and comparison seronegative women enrolled in a prospective U.S. cohort study were followed with semiannual Pap testing, with colposcopy for any abnormality. Histology results were retrieved to identify CIN3+ (CIN3, adenocarcinoma in situ, and cancer and CIN2+ (CIN2 and CIN3+). Annual detection rates were calculated and risks compared using Cox analysis. Median follow-up (IQR) was 11.0 (5.4–17.2) years for HIV seronegative and 9.9 (2.5–16.0) for HIV seropositive women.

Results

CIN3+ was diagnosed in 139 (5%) HIV seropositive and 19 (2%) seronegative women (P < 0.0001), with CIN2+ in 316 (12%) and 34 (4%) (P < 0.0001). The annual CIN3+ detection rate was 0.6/100 person-years in HIV seropositive women and 0.2/100 person years in seronegative women (P < 0.0001). The CIN3+ detection rate fell after the first two years of study, from 0.9/100 person-years among HIV seropositive women to 0.4/100 person-years during subsequent follow-up (P < 0.0001). CIN2+ incidence among these women fell similarly with time, from 2.5/100 person-years during the first two years after enrollment to 0.9/100 person-years subsequently (p < 0.0001). In Cox analyses controlling for age, the hazard ratio for HIV seropositive women with CD4 counts <200/cmm compared to HIV seronegative women was 8.1 (95% C.I. 4.8, 13.8) for CIN3+ and 9.3 (95% C.I. 6.3, 13.7) for CIN2+ (P < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Although HIV seropositive women have more CIN3+ than seronegative women, CIN3+ is uncommon and becomes even less frequent after initiation of regular cervical screening.

Keywords: Cervical cancer prevention, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, HIV in women

Introduction

Compared to HIV seronegative women, HIV seropositive women face a higher risk for coinfection by human papillomaviruses (HPV) and abnormal Pap tests (1–3). Despite this, cancer incidence in HIV seropositive women receiving cervical cancer prevention measures was not significantly increased (4, 5).

The reasons underlying this discrepancy are unclear. Women in a cancer prevention program may have a high frequency of precancers that are identified and eliminated, blocking oncogenesis. However, cervical treatments for HPV-related disease were not common among women in two U.S. HIV cohorts (7). Alternatively, HPV infections may progress rapidly to precancer and then cancer more rapidly in HIV seropositive than seronegative women, yet the disparity may only become apparent after years of observation. Even when assessed across time, most abnormal Paps in HIV seropositive women are atypical or low grade, not the high grade results strongly correlated with precancer (3). Cervical precancers may be similarly infrequent or may not progress over the short observation periods of most prior studies.

The objective of this study was to describe the incidence across time of cervical precancer among HIV seropositive and comparison seronegative U.S. women in a cancer prevention program.

Materials and Methods

The Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) is a U.S. multicenter cohort study of health outcomes among HIV seropositive women. The study also has followed at-risk HIV seronegative comparison women who were frequency matched for risk factors, including age, race/ethnicity, level of education, injection drug use since 1978, and total number of sexual partners since 1980. Enrollment began on October 3, 1994 at 6 study consortia and over time enrolled 4,068 women, including those enrolled during expansions from 2001–2002 and 2011–2012, and was designed to ensure that the cohort reflected the evolving HIV epidemic in U.S. women (8, 9). At each site, human subjects committees reviewed and approved the study, and all participants gave written informed consent. Follow up continues, but this analysis includes information on histologic outcomes through September 30, 2013.

According to study-wide protocol, single-slide conventional Pap smears were obtained every six months using spatula and brush for HIV seropositive and seronegative women. Colposcopy was required by study protocol for any epithelial cytologic abnormality, including ASCUS. HPV testing was performed for research only and was not used in clinical management, including for ASCUS triage. Biopsy results were interpreted at local sites and were not centrally reviewed. Abnormal results were categorized as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 1, 2, or 3, adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), or cancer. Unspecified high grade dysplasia was classified with CIN3. We examined CIN3 or worse (CIN3+) and CIN2 and worse (CIN2+) in separate analyses. Cervical disease treatments were identified by self-report, supplemented by medical record abstraction when available.

To minimize confusing prevalent with incident disease, women diagnosed with CIN3+ and CIN2+ within six months of study enrollment were excluded. Women who had hysterectomies at baseline were excluded, and women were censored at hysterectomy during follow-up. Those without follow-up were also excluded. Contingency tables were generated to assess baseline patient characteristics by HIV serostatus. Pearson’s chi-squared tests were used to compare baseline characteristics between HIV seropositive and seronegative women. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare medians. Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate the cumulative incidence. The incidence rates between HIV seropositive and HIV seronegative women were compared using Cox models with the normal approximation to the binomial distribution. And the incidence rates before 2 years and those after 2 years were compared using the bootstrapping method. All statistical tests defined significance as p < 0.05 using two-sided tests.

Results

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics at enrollment for the 3465 women at risk for CIN3+ during follow-up (900 HIV seronegative, 2565 HIV seropositive). The median age (interquartile range) for HIV seropositive women was 35 (30–41) years and for seronegative women was 33 (26–40) years (P < 0.0001). HIV seropositive women were less likely to be smokers at enrollment and more likely to have been abstinent during the six months before enrollment. Although the distribution of the reported lifetime number of male partners was different, with more HIV seropositive women reporting the extremes of partner number, the median number of partners was 10 for both HIV seropositive and seronegative women.

Table 1.

Demographic, behavioral, and medical characteristics at enrollment of HIV seropositive (HIV+) and seronegative (HIV−) women followed for incident CIN3+. (N, %)

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 3465) | HIV− (N = 900) | HIV+ (N = 2565) | p-value HIV+ vs HIV− |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | 0.75 | |||

| White | 489 (14) | 119 (13) | 370 (14) | |

| Hispanic | 897 (26) | 236 (26) | 661 (26) | |

| Black | 1957 (56) | 510 (57) | 1447 (56) | |

| Other | 122 (4) | 35 (4) | 87 (3) | |

| Smoking status | 0.01 | |||

| Never smoked | 1158 (34) | 278 (31) | 880 (34) | |

| Former smoker | 514 (15) | 119 (13) | 395 (15) | |

| Current smoker | 1778 (52) | 500 (56) | 1278 (50) | |

| Education | 0.14 | |||

| Less than high school | 1288 (37) | 310 (35) | 978 (38) | |

| high school | 1034 (30) | 272 (30) | 762 (30) | |

| Beyond high school | 1134 (33) | 312 (35) | 822 (32) | |

| Lifetime # of male sexual partners | 0.001 | |||

| <5 | 769 (23) | 167 (19) | 602 (24) | |

| 5–9 | 716 (21) | 194 (22) | 522 (21) | |

| 10–49 | 1142 (34) | 340 (38) | 802 (32) | |

| >=50 | 779 (23) | 189 (21) | 590 (23) | |

| # of male sexual partner in past 6 months | <.0001 | |||

| 0 | 865 (26) | 152 (17) | 713 (29) | |

| 1 | 1833 (54) | 439 (49) | 1394 (56) | |

| 2 | 372 (11) | 146 (16) | 226 (9) | |

| >=3 | 317 (9) | 158 (18) | 159 (6) | |

| CD4+ cell count/cmm | ||||

| >500 | 889 (36) | |||

| 200–500 | 1099 (44) | |||

| <200 | 505 (20) | |||

| HIV viral load (copies/cmm) | ||||

| <=4000 | 1057 (42) | |||

| 4001–20,000 | 518 (21) | |||

| 20,001–100,000 | 532 (21) | |||

| >100,000 | 403 (16) | |||

| Ever AIDS | ||||

| No | 2037 (79) | |||

| Yes | 528 (21) |

HIV-related disease characteristics among seropositive women are summarized in Table 1. Most HIV seropositive women had CD4 cell counts >200/cmm, with HIV RNA levels below or just above the threshold for detection at study initiation, which for most women was <4,000 copies/cmm. Most had never been diagnosed with AIDS.

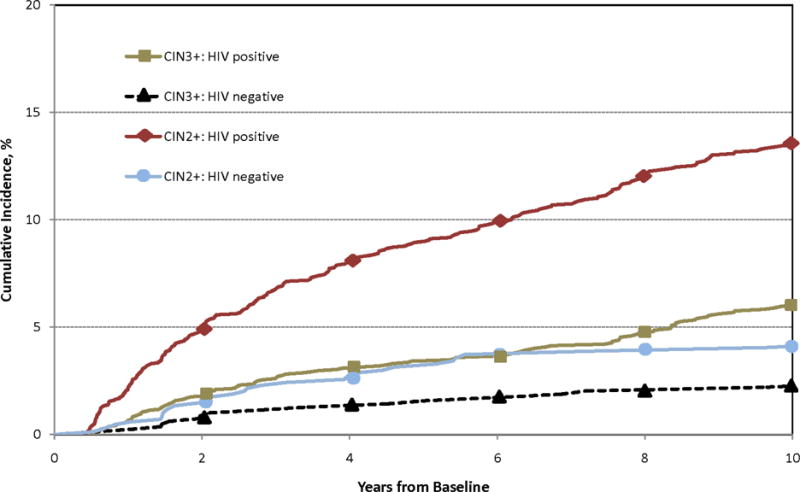

Median follow-up (IQR) was 11.0 (5.4–17.2) years for HIV seronegative and 9.9 (2.5–16.0) for HIV seropositive women. Follow-up rates for HIV seropositive and seronegative women at three years were 86% and 80%, at five years were 82% and 74% and at 10 years were 71% and 62%. Only 19 (2%) HIV seronegative women were diagnosed with CIN3+, while CIN3+ was found in 139 (5%) of HIV seropositive women (P < 0.0001). The risk of CIN2+ was substantially greater, occurring in 34 (4%) HIV seronegative women and 316 (12%) HIV seropositive women (P < 0.0001). The annual detection rate of CIN3+ was 0.6/100 person-years in HIV seropositive women and 0.2/100 person years in seronegative women (P < 0.0001). Similar rates for CIN2+ were 1.4 and 0.4/100 person-years (P < 0.0001).

The annual detection rate of CIN3+ and CIN2+ fell over time. We estimated the detection rate of these endpoints before and after the first two years after enrollment, excluding presumed prevalent disease discovered during the first six months of study. The annual rate of CIN3+ detection among HIV seropositive women was 0.9/100 person-years during the first two years of study and 0.4/100 person-years during subsequent follow-up (P < 0.0001). CIN2+ incidence among these women fell similarly with time, from 2.5/100 person-years during the first two years after enrollment to 0.9/100 person-years subsequently (P < 0.001). Incidence was lower among HIV seronegative women but also fell with time: CIN3+ incidence dropped from 0.4/100 person-years during the first two years to 0.1/100 person-years thereafter (P = 0.02), while CIN2+ incidence decreased from 0.7/100 person-years early in study to 0.2/100 person-years afterward (P = 0.03). Incidence of CIN3+ and CIN2+ was higher among HIV seropositive than seronegative women at both time points (P < 0.0001), except that the difference in CIN3+ during the first years was not significant (P = 0.07). The decline in risk after two years persisted among HIV seropositive women after controlling for CD4 count women and for age (HR 0.18 after two years, 95% C.I. 0.08, 0.40, P < 0.0001). There was insufficient data to conduct a similar multivariate analysis among HIV seronegative women.

If the observed increased risk of CIN3+ and CIN2+ in HIV seropositive women is related to immunosuppression, then risk should rise with more severe immunosuppression. In fact, the incidence of CIN3+ was 0.2/100 person-years (95% C.I. 0.1, 0.3) among HIV seronegative women, 0.5 (95% C.I. 0.3, 0.6, p = 0.003 compared to HIV seronegative women) among HIV seropositive women with CD4 counts >500/cmm, 0.5 (95% C.I. 0.4, 0.7, p = 0.0003) among women with CD4 counts 200–500/cmm, and 1.0 (95% C.I. 0.7, 1.3, P < 0.0001) among women with CD4 counts <200/cmm. CIN2+ risk rose similarly, from 0.4/100 person-years (95% C.I. 0.2, 0.5) among HIV seronegative women to 1.2 (95% C.I. 0.9, 1.4, P < 0.0001 compared to HIV seronegative women) among HIV seropositive women with CD4 counts >500/cmm, 1.4 (95% C.I. 1.1, 1.6, P < 0.0001) for women with CD4 counts 200–500/cmm, and 2.3 (95% C.I. 1.7, 2.8, P < 0.0001) among women with CD4 counts <200/cmm. Although significant, these results may obscure the impact of CD4 count on CIN3+ and CIN2+, as levels may vary over time. In analysis adjusting for CD4 count as a time-varying factor, we observed a progressive rise in CIN3+ and CIN2+ risk as CD4 counts fell (Table 2). In Cox analyses controlling for age and the timing of diagnosis, the hazard ratio for HIV seropositive women with CD4 counts <200/cmm compared to HIV seronegative women was 4.6 (95% C.I. 3.0, 7.2) for CIN3+ and 3.5 (95% C.I. 2.6, 4.7) for CIN2+ (P < 0.0001 for both).

Table 2.

Association of time-dependent CD4 count with incidence of CIN3+ and CIN2+, controlling for timing of diagnosis and age CIN3+

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (HR) | 95% LCL | 95% UCL | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing of diagnosis | Initial 2 yrs (ref) | 1 | |||

| After 2yrs | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.40 | <.0001 | |

| CD4+ T-cell count | >500 (ref) | 1 | |||

| 200–500 | 1.40 | 0.88 | 2.21 | 0.16 | |

| <200 | 4.62 | 2.95 | 7.22 | <.0001 | |

| Age | <30 (ref) | 1 | |||

| 30–34 | 0.87 | 0.46 | 1.65 | 0.66 | |

| 35–39 | 0.94 | 0.51 | 1.71 | 0.84 | |

| 40–44 | 0.66 | 0.34 | 1.26 | 0.21 | |

| >=45 | 0.73 | 0.38 | 1.39 | 0.33 | |

| a. CIN2+ | |||||

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (HR) | 95% LCL | 95% UCL | P-value | |

| Timing of diagnosis | Initial 2 yrs (ref) | 1 | |||

| After 2yrs | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.51 | <.0001 | |

| CD4+ T-cell count/cmm | >500 (ref) | 1 | |||

| 200–500 | 1.52 | 1.14 | 2.03 | 0.004 | |

| <200 | 3.45 | 2.56 | 4.65 | <.0001 | |

| Age | <30 (ref) | 1 | |||

| 30–34 | 0.60 | 0.41 | 0.87 | 0.01 | |

| 35–39 | 0.69 | 0.49 | 0.98 | 0.04 | |

| 40–44 | 0.39 | 0.26 | 0.59 | <.0001 | |

| >=45 | 0.46 | 0.31 | 0.69 | 0.0001 | |

We further explored factors associated with the incidence of CIN3+ and CIN2+. As shown in Table 3, CD4 count remained strongly associated with both CIN3+ and CIN2+. Smoking was associated with higher and increasing age with lower risk. Lifetime number of sexual partners was not associated with either CIN3+ or CIN2+ after controlling for these factors. Recent number of sexual partners was linked to CIN2+ but not CIN3+.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of correlates of CIN3+ and CIN2+.

| a. CIN3+ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (HR) | 95% LCL | 95% UCL | P-value | |

| CD4+ T-cell count | HIV- (ref) | 1 | <.00011 | ||

| >500 | 1.88 | 1.04 | 3.40 | 0.04 | |

| 200–500 | 2.45 | 1.40 | 4.27 | 0.002 | |

| <200 | 7.78 | 4.51 | 13.42 | <.0001 | |

| Age | <30 (ref) | 1 | |||

| 30–34 | 0.66 | 0.37 | 1.17 | 0.15 | |

| 35–39 | 0.64 | 0.37 | 1.10 | 0.11 | |

| 40–44 | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.83 | 0.01 | |

| >=45 | 0.53 | 0.29 | 0.97 | 0.04 | |

| Smoking | Never smoked (ref) | 1 | |||

| Former smoker | 0.85 | 0.47 | 1.54 | 0.60 | |

| Current smoker | 2.08 | 1.35 | 3.21 | 0.001 | |

| Life-time # of male sexual partner | <5 (ref) | 1 | |||

| 5–9 | 1.71 | 1.03 | 2.84 | 0.04 | |

| 10–49 | 1.11 | 0.67 | 1.85 | 0.69 | |

| >=50 | 1.24 | 0.72 | 2.13 | 0.43 | |

| # of male sexual partner in past 6 months | 0 (ref) | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1.20 | 0.83 | 1.75 | 0.34 | |

| 2 | 0.68 | 0.30 | 1.54 | 0.35 | |

| >=3 | 0.62 | 0.22 | 1.78 | 0.37 | |

| b. CIN2+ | |||||

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (HR) | 95% LCL | 95% UCL | P-value | |

| CD4+ T-cell count | HIV- (ref) | 1 | <.0001* | ||

| >500 | 2.86 | 1.89 | 4.33 | <.0001 | |

| 200–500 | 4.23 | 2.86 | 6.25 | <.0001 | |

| <200 | 9.50 | 6.36 | 14.18 | <.0001 | |

| Age | <30 (ref) | 1 | |||

| 30–34 | 0.53 | 0.37 | 0.76 | 0.001 | |

| 35–39 | 0.62 | 0.45 | 0.86 | 0.004 | |

| 40–44 | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.48 | <.0001 | |

| >=45 | 0.44 | 0.30 | 0.65 | <.0001 | |

| Smoking | Never smoked (ref) | 1 | |||

| Former smoker | 0.96 | 0.66 | 1.39 | 0.83 | |

| Current smoker | 1.87 | 1.41 | 2.47 | <.0001 | |

| Life-time # of male sexual partner | <5 (ref) | 1 | |||

| 5–9 | 1.13 | 0.81 | 1.57 | 0.49 | |

| 10–49 | 1.02 | 0.74 | 1.40 | 0.92 | |

| >=50 | 0.98 | 0.69 | 1.39 | 0.90 | |

| # of male sexual partner in past 6 months | 0 (ref) | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1.56 | 1.19 | 2.05 | 0.002 | |

| 2 | 1.69 | 1.09 | 2.60 | 0.02 | |

| >=3 | 1.46 | 0.84 | 2.53 | 0.18 | |

P for trend.

P for trend.

We assessed whether the incidence of CIN3+ and CIN2+ might have been reduced by treatment of lesser lesions. In all, 1270 women reported cervical disease treatment during follow-up (1040 HIV seropositive and 230 HIV seronegative women). However, incidence of CIN2+ did not appear to decline after treatment. Among treated women, the annual incidence of CIN3+ before treatment was 0.5/100 person-years among HIV seropositive women while that of HIV seronegative women was 0.2/100 person-years. After treatment, CIN3+ incidence was 0.7/100 person-years among HIV seropositive and 0.3/100 person-years among HIV seronegative women. While the rate of CIN3+ among HIV seropositive women was higher than among HIV seronegative women before and after self-reported treatment, the difference reached statistical significance only during the pre-treatment interval (P = 0.01), not during the post-treatment interval (P = 0.15). HIV seropositive women who were treated for cervical disease also had higher rates of CIN2+ before and after treatment: 1.6 vs 0.4/100 person-years among HIV seronegative women before treatment (P < 0.0001) and 1.7 vs 0.4/100 person-years after treatment (P = 0.0002).

Comment

HIV seropositive women have higher risk for CIN3+ than seronegative women, but their absolute risk is low across years of observation, well less than 1% annually and 5% across a median of 10 years of observation. Women with HIV warrant careful cervical cancer screening and meticulous investigation after abnormal screening results, with treatment for histologically confirmed precancers. However, HIV seropositive women with equivocal abnormalities should not be subjected to treatment solely because they are perceived to be at high risk. Risk rises with increasing immunosuppression as measured by CD4 count, and more aggressive intervention may be appropriate for more severely immunosuppressed women, provided expected survival in the face of HIV disease remains substantial.

CIN2+ is more common than CIN3+ in HIV seropositive women, occurring in about 1% annually and 12% during 10-year follow-up. This risk is also higher than in HIV seronegative women. The oncogenic potential of CIN2 is uncertain, as it appears to include some lesions with substantial and others with little malignant potential (10). Nevertheless, treatment of CIN2 may have aborted development of CIN3+ in some women. Cervical disease treatments in WIHS were done off-study, though sometimes in the same clinical sites. Some were tracked by participant self-report, which may undercount treatments. Cervical cancer incidence in HIV seropositive women in our cervical cancer prevention program remains low across a decade of observation (5). The low absolute risk of CIN3+ across a similar time span suggest that women with HIV receiving care that includes cervical cancer prevention do not face an impending epidemic of cervical cancer that has yet to manifest itself.

The incidence of CIN3+ fell after the first two years of our study, and this was true for HIV seropositive women regardless of age and CD4 count. Although we tried to minimize the impact of prevalent disease on incidence estimates by excluding cases diagnosed during the first six months after enrollment, cytology is insensitive and noncompliance with colposcopy referral was a problem early in the study. The higher initial detection rate we observed may be attributable in part to delayed diagnosis of prevalent lesions. In addition, treatment of CIN1 accounted for more than a third of all cervical treatments during initial years of the study (7), and we cannot exclude the possibility that removal of lesser precursors may have reduced subsequent risk for CIN3+ and CIN2+. Alternatively, initiation of HAART after study enrollment and corresponding engagement in HIV care might have reduced risk for CIN3+ and CIN2+ by reducing immunosuppression and facilitating immune-mediated clearance of HPV-induced cervical lesions beyond what can be addressed by CD4 count (11).

Regardless of the cause of the lower incidence of CIN3+ and CIN2+ after two years in study, the finding supports the concept that HIV seropositive women receiving regular gynecologic care are at low absolute risk for CIN3+. We have shown that the risk for CIN3+ after serial negative Pap tests or a single combination Pap/HPV cotest is low (12, 13). Despite a statistically increased risk of CIN3+, the low absolute risk for CIN3+ among HIV seropositive women after two years in care reinforces the recommendation that after initial negative cervical cancer screening tests, subsequent screening intervals can be safely lengthened.

Neither recent nor lifetime number of sexual partners was associated with CIN3+ after controlling for CD4 count, age, and smoking. This suggests that host factors that determine HPV clearance versus persistence, as well as the subsequent accumulation of somatic epigenetic and genetic changes, may be more important than simple HPV exposure in determining risk for cervical precancer and cancer among HIV seropositive women. Recent number of sexual partners was associated with CIN2+ but not CIN3+ after controlling for CD4 count, age, and smoking. This is consistent with the concept that many cases of CIN2 are recently acquired HPV infections of uncertain oncogenic potential.

This study has several strengths, including the prospective nature of the study and the use of CIN3+ as an endpoint, where most prior studies have been retrospective and have relied on cervical cytology, which can be nonspecific and may overestimate CIN2+ (14).

Our results are limited by several factors. Biopsies were not centrally reviewed, and some misclassification may have occurred. Nevertheless, the low incidence of cervical cancer in our cohort is consistent with a relatively low incidence of cervical precancer and suggests few cases were missed. Cervical disease treatments were not provided in this observational study and self-reporting may have undercounted treatment. Some women with CIN1 were treated early in the study. Although this might have reduced progression of lower grade CIN to CIN3+, our conclusion that new CIN3+ is uncommon in HIV seropositive women in a cancer prevention program remains valid. Women in WIHS are screened with cytology semiannually, more frequently than under current guidelines, but HIV seropositive women with negative screening results are at low risk for CIN3+ (12, 13) and similar low incidence should result from standard screening. Colposcopy compliance among women with HIV can be suboptimal (15), but serial observation over years should have identified most women with oncogenic lesions. HIV seropositive women who have not been screened may face higher risk, as reflected by the higher incidence of CIN3+ identified soon after study launch. We cannot exclude the possibility that CIN3+ incidence may rise after periods longer than we observed women, but WIHS is ongoing.

Despite an increased relative risk of cervical disease compared to HIV seronegative women, the low absolute incidence of CIN3+ in HIV seropositive women warrants cautious management of abnormalities detected in cervical cancer prevention programs. Clinicians need not rush to treat minor lesions out of fear of rapid progression. In fact, progression of CIN1 is uncommon (16), the negative predictive value of repeated Pap testing is good (17), and negative colposcopy after borderline cervical abnormalities is reassuring (18). Longer studies, including WIHS as it continues into its third decade of follow-up, should better define the long-term cancer risk in the face of frequent carcinogenic HPV infection and abnormal cytology.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative incidence of CIN3+ and CIN2+ among HIV seropositive and seronegative women. For both, P < 0.0001 by log-rank test.

Acknowledgments

Clinical data and specimens in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group with centers (Principal Investigators) at New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff); Washington DC Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); The Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); Data Coordinating Center (Stephen Gange). The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UO1-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590) and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (UO1-HD-32632). The study is co-funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Funding is also provided by the National Center for Research Resources (UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional support, including for statistical analysis, was provided by R01 CA85178 (Howard Strickler).

Funding source: Federal grants. See acknowledgement Reprints will not be available

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure of interests: Dr. Darragh reported potential conflicts. These include:

Hologic: Research supplies for anal cytology, honorarium for webinar on anal cancer screening, October 2012 OncoHealth Advisory Board, Stock options, ongoing

Roche, October 2013: Honorarium paid to UCSF, October 2013

No other authors report potential financial conflicts of interest related to the study.

A study of Dr. Strickler’s involves free blinded testing using HPV E6/E7 protein assays by Arbor Vita (CA, USA), p16/Ki67 cytology by MTM Laboratories / Ventura – Roche (Mannheim, Germany), MCM-2/TOP2A cytology, BD Diagnostics (NJ, USA). No financial payments to Dr Strickler or his home institution were received.

No other authors reported potential financial conflicts of interest.

Contribution to authorship: Dr Massad conceived the analysis, contributed patient data, and wrote the first manuscript draft. Drs D’Souza, Darragh, Minkoff, Assaye, Wright, and Evans, and Ms. Sanchez-Keeland all contributed to study execution and manuscript development. Drs. Xie and Strickler contributed to concept development and performed statistical analyses. All have approved the final manuscript for submission to BJOG.

Details of ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained at every site and subsite and was reapproved repeatedly over the past 20 years of the study. Documentation is not provided because of the large number of approvals required.

Contributor Information

L. Stewart MASSAD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO

Xianhong XIE, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY

Gypsyamber D’SOUZA, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD

Teresa M. DARRAGH, Departments of Pathology and Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, University of California, San Francisco, CA

Howard MINKOFF, Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY

Rodney WRIGHT, Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY

Christine COLIE, Georgetown University, Washington, DC

Ms. Lorraine SANCHEZ-KEELAND, Department of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA

Howard D. STRICKLER, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY

References

- 1.Palefsky JM, Minkoff H, Kalish LA, Levine A, Sacks HS, Garcia P, Young M, Melnick S, Miotti P, Burk R. Cervicovaginal human papillomavirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV)-positive and high-risk HIV-negative women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:226–36. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massad LS, Riester KA, Anastos KM, Fruchter RG, Palefsky JM, Burk RD, Burns D, Greenblatt RM, Muderspach LI, Miotti P. Prevalence and predictors of squamous cell abnormalities in Papanicolaou smears from women infected with HIV-1. Women’s Interagency HIV Study Group. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;21:33–41. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199905010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massad LS, Seaberg EC, Wright RL, Darragh T, Lee YC, Colie C, Burk R, Strickler HD, Watts DH. Squamous cervical lesions in women with human immunodeficiency virus: long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1388–93. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181744619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massad LS, Seaberg EC, Watts DH, Hessol NA, Melnick S, Bitterman P, Anastos K, Silver S, Levine AM, Minkoff H. Low incidence of invasive cervical cancer among HIV infected US women in a prevention program. AIDS. 2004;18:109–13. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200401020-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massad LS, Seaberg EC, Watts DH, Minkoff H, Levine AM, Henry D, Colie C, Darragh TM, Hessol NA. Long-term incidence of cervical cancer in women with HIV. Cancer. 2009;115:524–30. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strickler HD, Palefsky JM, Shah KV, Anastos K, Klein RS, Minkoff H, Duerr A, Massad LS, Celentano DD, Hall C, Fazzari M, Cu-Uvin S, Bacon M, Schuman P, Levine AM, Durante AJ, Gange S, Melnick S, Burk RD. Human papillomavirus type 16 and immune status in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1062–71. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.14.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massad LS, Fazzari MJ, Anastos K, Klein RS, Minkoff H, Jamieson DJ, Duerr A, Celentano D, Gange S, Cu-Uvin S, Young M, Watts DH, Levine AM, Schuman P, Harris TG, Strickler HD. Outcomes after treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia among women with HIV. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11:90–7. doi: 10.1097/01.lgt.0000245038.06977.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Martin-Preston S, Weber K, Kalish LA, Miotti P, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Epidemiol. 1998;9:117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bacon M, von Wyl V, Alden C, Sharp G, Robison E, Hessol N, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diag Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1013. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT, Heller DS, Henry MR, Luff RD, et al. for the LAST Project Work Groups The Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology Standardization Project for HPV-Associated Lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16:205–42. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31825c31dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minkoff H, Zhong Y, Burk RD, Palefsky JM, Xue X, Watts DH, et al. Influence of adherent and effective antiretroviral therapy use on human papillomavirus infection and squamous intraepithelial lesions in human immunodeficiency virus-positive women. J Infect Dis. 2010 Mar;201(5):681–90. doi: 10.1086/650467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massad LS, D’Souza G, Tian F, Minkoff H, Cohen M, Wright RL, et al. Negative predictive value of pap testing: implications for screening intervals for women with human immunodeficiency virus. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:791–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31826a8bbd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller MJ, Burk RD, Xie X, Anastos K, Massad LS, Minkoff H, et al. Risk of cervical precancer and cancer among HIV-infected women with normal cervical cytology and no evidence of oncogenic HPV infection. JAMA. 2012;308:362–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massad LS, Schneider M, Watts H, Darragh T, Abulafia O, Salzer E, et al. Correlating Papanicolaou smears, colposcopic impression and biopsy. Results from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. J Lower Genital Tract Dis. 2001;5:212–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cejtin HE, Komaroff E, Massad LS, Korn A, Schmidt JB, Eisenberger-Matiyahu D, et al. Adherence to colposcopy among women with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999 Nov 1;22(3):247–52. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199911010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massad LS, Evans CT, Minkoff H, Watts DH, Strickler HD, Darragh T, et al. Natural history of grade 1 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in women with human immunodeficiency virus. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1077–85. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000143256.63961.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massad LS, D’Souza G, Tian F, Minkoff H, Cohen M, Wright RL, et al. Negative predictive value of Pap testing: Implications for screening intervals for women with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:791–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31826a8bbd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massad LS, Evans CT, Strickler HD, Burk RD, Watts DH, Cashin L, et al. Outcome after negative colposcopy among human immunodeficiency virus-infected women with borderline cytologic abnormalities. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:525–32. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000172429.45130.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]