Abstract

Objective

Little is known about factors influencing the rate of progression of Alzheimer’s dementia. Using data from the Cache County Dementia Progression Study, we examined the link between clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild Alzheimer’s dementia and progression to severe dementia or death.

Method

The Cache County Dementia Progression Study is a longitudinal study of dementia progression in incident cases of the condition. Survival analyses included unadjusted Kaplan-Meier plots and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models. Hazard ratio estimates controlled for age of dementia onset, dementia duration at baseline, gender, education level, General Medical Health Rating, and apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 (APOE-ε4) genotype.

Results

Three hundred thirty-five patients with incident Alzheimer’s dementia were studied. Sixty-eight (20%) developed severe dementia over the follow-up. Psychosis (hazard ratio=2.007, p=0.028), agitation/aggression (hazard ratio=2.946, p=0.004), and any one clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptom (domain score of ≥4, hazard ratio=2.682, p=0.001) were associated with more rapid progression to severe dementia. Psychosis (hazard ratio=1.537, p=0.011), affective symptoms (hazard ratio=1.510, p=0.003), agitation/aggression (hazard ratio=1.942, p=0.004), mildly symptomatic neuropsychiatric symptoms (domain score of 1–3, hazard ratio=1.448, p=0.024), and clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptoms (hazard ratio=1.951, p=<0.001) were associated with earlier death.

Conclusions

Specific neuropsychiatric symptoms are associated with shorter survival time from mild Alzheimer’s dementia to severe dementia and/or death. The treatment of specific neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild Alzheimer’s dementia should be examined for its potential to delay time to severe dementia or death.

Keywords: incident dementia, severe dementia, severe Alzheimer’s disease, rate of decline, progression, mortality

Introduction

The increasing number of people diagnosed with dementia is a well-known phenomenon driven by an aging population and increased public recognition of its signs and symptoms (1). The United States annual costs for health care, long-term care, and hospice care of people with dementia are expected to increase from $200 billion in 2012 to $1.1 trillion in 2050 (2). Many of these costs are related to the long-term care required for those with severe dementia. Delaying progression to late-stage dementia has the potential of increasing meaningful time spent with those afflicted. Several studies have examined predictors of progression from onset of dementia to severe dementia (3–5). Factors shown to accelerate progression include younger age of onset, higher level of education, greater severity of cognitive impairment (defined as lower baseline modified Mini-Mental State Examination or higher clinical dementia rating scores), greater severity of behavioral disturbance, and presence of psychosis or other neuropsychiatric symptom (3, 4). Storandt et al. showed that rate of decline on psychometric testing accelerates as dementia severity worsens, but in their study no individual test was predictive of dementia progression (i.e. nursing home placement) (6).

Using the same population-based study utilized here, the Cache County Dementia Progression Study, Rabins et al. (5) found that female gender, less than high school education, and at least one clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptom at baseline were predictive of shorter time to severe Alzheimer’s dementia. Age at onset of dementia was predictive in that the youngest (68–80) and oldest (87–104) tertiles of age progressed to severe Alzheimer’s dementia faster than the middle tertile of age (81–86). In addition, subjects with mild or at least one clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptom and subjects with worse health were more likely to progress to severe dementia or death. The present article aims to expand on this work.

The Cache County Dementia Progression Study (7, 8) is a longitudinal study with regular reassessment of cognition and detailed collection of neuropsychiatric symptom data. Although it is known that neuropsychiatric symptoms are associated with a worse prognosis in dementia (9), the relationship between individual neuropsychiatric symptom or clusters of neuropsychiatric symptoms and progression to severe dementia or death is not fully understood. In this analysis we examine the association between clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptoms, including psychotic and affective clusters of symptoms, and progression to severe dementia and/or death. We hypothesized that the presence of psychotic symptoms, and the individual symptom of agitation/aggression, would predict shorter time to severe dementia.

Method

Methods of the Cache County Study and the Dementia Progression Study have been described in detail elsewhere (7, 8). Briefly, all permanent residents of Cache County, Utah who were 65 years or older in January 1995 (n=5677) were invited into the study. We enrolled 5092 (90%) in Wave 1 of the Cache County Study, all of whom were screened for dementia in a multi-staged assessment protocol. Rate of dementia was 9.6% in the prevalence wave, similar to many epidemiological samples. Individuals were reassessed at 3- to 5-year intervals (mean = 3.53, standard deviation = 0.6) in three incidence waves. A consensus panel made diagnoses of dementia and dementia type. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia followed the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria (10). The Dementia Progression Study (11) limited analyses to those individuals from the Cache County study who converted from no dementia to Alzheimer’s dementia with follow-up rates, excluding mortality, exceeding 90%. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Severe Alzheimer’s dementia was defined as a mini-mental state examination (12) score of ≤10 or clinical dementia rating scale (13) score equal to 3 (severe). If only the mini-mental state examination criteria was met, inclusion required a clinical dementia rating score of at least 2 (moderate) and if only clinical dementia rating criteria was met, inclusion required a mini-mental state examination score of less than 16.

To identify potentially predictive neuropsychiatric symptoms, the 10-item neuropsychiatric inventory (14) was utilized. The neuropsychiatric inventory is a fully structured informant-based interview that provides a systematic assessment of 10 neuropsychiatric symptom domains: delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, depression/dysphoria, anxiety, elation/euphoria, apathy/indifference, disinhibition, irritability/lability, and aberrant motor behavior. The presence of symptoms in each domain during the past 30 days was queried and if endorsed, specific follow up questions were asked to clarify the nature of the symptoms, including degree of change from premorbid and treatment. Once the disturbances relevant to each domain were defined, the informant was asked about the frequency of these on a 4-point scale from 1 (occasionally) to 4 (very frequently, more than once a day). The informant was also asked to rate the severity of the behavior on a 3-point severity scale (mild, moderate, or severe). Neuropsychiatric inventory scores were obtained at the time of diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia and scored as follows: (1) presence of at least one of the psychosis neuropsychiatric symptom domains (delusions and hallucinations), (2) presence of at least one of the affective neuropsychiatric symptom domains (depression, anxiety, and irritability), (3) presence of the individual neuropsychiatric symptom of apathy/indifference or agitation/aggression, and (4) frequency × severity neuropsychiatric inventory score across all domains trichotomized as no symptoms, at least one neuropsychiatric symptom domain score 1 to 3 (mild), or at least one neuropsychiatric symptom domain score ≥4 (clinically significant).

To identify individual factors associated with time to develop severe Alzheimer’s dementia, we constructed unadjusted Kaplan-Meier plots for each of the neuropsychiatric inventory groups described above. In addition, we ran bivariate and multi-variate Cox proportional hazard models. Based on the results from Rabins et al.(5), the hazard models were controlled for age of dementia onset, gender, education level, and General Medical Health Rating(15). General Medical Health Rating scores were obtained at the time of diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia and were coded as excellent, good, or fair/poor. In addition, given results of prior studies (16), we also controlled for apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 (APOE-ε4) genotype status, with positive designation coded if at least one ε4 allele was present. Lastly, we controlled for time between dementia onset and diagnosis (dementia duration at baseline). The same analyses were run for association with time to death. All analyses met the proportional hazards assumption and were conducted with SPSS version 21 (IBM corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

Three hundred thirty-five incident cases of possible or probable Alzheimer’s dementia were identified. Mean age at onset was 84.3 (standard deviation = 6.4) years, and mean time between dementia onset and diagnosis was 1.7 (standard deviation = 1.3) years. Sixty-eight (20% of the incident sample) developed severe Alzheimer’s dementia over the course of the study (1995–2009). After extended follow-up through October 21, 2010, 273 individuals were deceased. Median time to severe Alzheimer’s dementia for the sample was 8.4 years (95% confidence interval: 7.6–9.2) and to death was 5.742 years (95% confidence interval: 5.423–6.061). Age of onset showed a nonlinear relationship for time to severe Alzheimer’s dementia and a linear association with time to death. Global Medical Health Rating was not associated with time to severe Alzheimer’s dementia, but was associated with time to death and those with poor/fair scores had 1.6 times the death hazard compared to good/excellent (neuropsychiatric symptom results were not affected significantly by this).

Neuropsychiatric symptoms were common, with 50.9% of the sample having at least one neuropsychiatric symptom. The baseline percentages of the neuropsychiatric symptom clusters were as follows: psychosis cluster – 18.1% and affective cluster – 38.8%. The individual neuropsychiatric symptom domain of apathy/indifference was seen in 16.9% of individuals at baseline and the individual domain of agitation/aggression was seen in 10% of individuals. At baseline, 25.9% of individuals had at least one mild neuropsychiatric symptom and 25.0% of individuals had at least one clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptom.

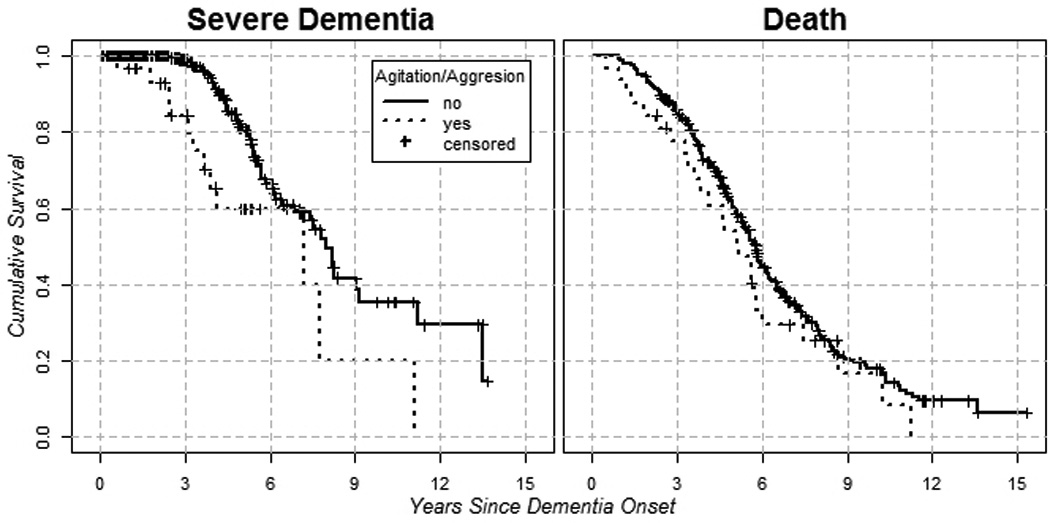

The results of the bivariate and multi-variable Cox regression models (controlled for age of dementia onset, dementia duration at baseline, gender, education level, Global Medical Health Rating, and APOE- ε4 status) are in Table 1 for hazard of severe dementia and Table 2 for hazard of death. The psychosis cluster (hazard ratio = 2.007, p=0.028), agitation/aggression (hazard ratio = 2.946, p=0.004), and at least one clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptom (hazard ratio = 2.682, p=0.001) were predictive of progression to severe dementia. The psychosis cluster (hazard ratio = 1.537, p=0.011), affective cluster (hazard ratio = 1.510, p=0.003), agitation/aggression (hazard ratio = 1.942, p=0.004), at least one mild neuropsychiatric symptom (hazard ratio = 1.448, p=0.024), and at least one clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptom (hazard ratio = 1.951, p=<0.001) were predictive of progression to death. Figure 1 shows unadjusted Kaplan-Meier plots for the outcome of severe dementia and death as predicted by agitation/aggression and is meant to serve as a proxy illustration for other predictors as well.

TABLE 1.

Multivariate1 Cox regression models for time to severe dementia

| Psychosis Cluster | Affective Cluster | Agitation/Aggression | Apathy/Indifference | Neuropsychiatric Inventory Significance2 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazard Ratio |

P-value | Hazard Ratio |

P-value | Hazard Ratio |

P-value | Hazard Ratio |

P-value | Hazard Ratio |

P-value | ||

| Unadjusted, bivariate value3 | 2.024 | 0.018 | 1.387 | 0.191 | 2.321 | 0.009 | 1.176 | 0.604 | --* (1.214/2.129) |

0.025* (0.560/0.008) |

||

| ADJUSTED MODEL | Alzheimer’s dementia onset age | 0.290 | <0.001 | 0.313 | <0.001 | 0.351 | 0.001 | 0.279 | <0.001 | 0.295 | <0.001 | |

| Alzheimer’s dementia onset age squared | 1.008 | <0.001 | 1.007 | <0.001 | 1.007 | 0.001 | 1.008 | <0.001 | 1.008 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 1.949 | 0.031 | 1.888 | 0.038 | 1.885 | 0.039 | 1.998 | 0.025 | 1.852 | 0.047 | ||

| Education4 | 1.791 | 0.79 | 1.910 | 0.048 | 1.934 | 0.041 | 1.888 | 0.56 | 0.756 | 0.095 | ||

| Apolipoprotein E – e4 Carrier | 0.940 | 0.823 | 1.076 | 0.767 | 1.109 | 0.706 | 1.070 | 0.808 | 1.106 | 0.711 | ||

| Global medical health rating | 1.554 | 0.140 | 1.585 | 0.128 | 1.511 | 0.174 | 1.527 | 0.146 | 1.737 | 0.074 | ||

| Dementia duration at baseline | 0.811 | 0.026 | 0.827 | 0.042 | 0.753 | 0.006 | 0.821 | 0.038 | 0.763 | 0.005 | ||

| Psychosis Cluster | 2.007 | 0.028 | ||||||||||

| Affective Cluster | 1.512 | 0.119 | ||||||||||

| Agitation/Aggression | 2.946 | 0.004 | ||||||||||

| Apathy/Indifference | 1.552 | 0.172 | ||||||||||

| Neuropsychiatric inventory significance2 | ||||||||||||

| Trichotomized | -- | 0.002 | ||||||||||

| Mild symptom(s) | 1.077 | 0.832 | ||||||||||

| Clinically significant symptom(s) | 2.682 | 0.001 | ||||||||||

Cox regression models were controlled for age of dementia onset, dementia duration at baseline, gender, education level, global medical health rating, and apolipoprotein E – e4 status;

Neuropsychiatric inventory examined as a trichotomous variable (none vs. mild vs. clinically significant);

Bivariate unadjusted model for each neuropsychiatric inventory symptom or cluster;

Reference category is greater than or equal to high school;

Data is shown as trichotomized comparison followed in parentheses by mild symptoms vs. none / clinically significant symptoms vs. none

TABLE 2.

Multivariate1 Cox regression models for time to death

| Psychosis Cluster | Affective Cluster | Agitation/Aggression | Apathy/Indifference | Neuropsychiatric Inventory Significance2 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazard Ratio |

P-value | Hazard Ratio |

P-value | Hazard Ratio |

P-value | Hazard Ratio |

P-value | Hazard Ratio |

P-value | ||

| Unadjusted, bivariate value3 | 1.567 | 0.006 | 1.192 | 0.195 | 1.276 | 0.251 | 1.074 | 0.683 | --* (1.425/1.267) |

0.073* (0.029/0.147) |

||

| ADJUSTED MODEL | Alzheimer’s dementia onset age | 1.092 | <0.001 | 1.100 | <0.001 | 1.096 | <0.001 | 1.095 | <0.001 | 1.102 | <0.001 | |

| Female | 0.706 | 0.018 | 0.725 | 0.028 | 0.701 | 0.017 | 0.733 | 0.034 | 0.694 | 0.013 | ||

| Education4 | 1.226 | 0.229 | 1.268 | 0.160 | 1.278 | 0.148 | 1.269 | 0.173 | 1.221 | 0.242 | ||

| Apolipoprotein E – e4 Carrier | 1.067 | 0.656 | 1.114 | 0.451 | 1.168 | 0.282 | 1.116 | 0.443 | 1.134 | 0.385 | ||

| Global medical health rating | 1.593 | 0.002 | 1.560 | 0.004 | 1.558 | 0.004 | 1.622 | 0.002 | 1.577 | 0.003 | ||

| Dementia duration at baseline | 0.781 | <0.001 | 0.780 | <0.001 | 0.761 | 0.004 | 0.781 | <0.001 | 0.752 | <0.001 | ||

| Psychosis Cluster | 1.537 | 0.011 | ||||||||||

| Affective Cluster | 1.510 | 0.003 | ||||||||||

| Agitation/Aggression | 1.942 | 0.004 | ||||||||||

| Apathy/Indifference | 1.261 | 0.211 | ||||||||||

| Neuropsychiatric inventory significance2 | ||||||||||||

| Trichotomized | -- | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Mild symptom(s) | 1.448 | 0.024 | ||||||||||

| Clinically significant symptom(s) | 1.951 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

Cox regression models were controlled for age of dementia onset, dementia duration at baseline, gender, education level, global medical health rating, and apolipoprotein E – e4 status;

Neuropsychiatric inventory examined as a trichotomous variable (none vs. mild vs. clinically significant);

Bivariate unadjusted model for each neuropsychiatric inventory symptom or cluster;

Reference category is greater than or equal to high school;

Data is shown as trichotomized comparison followed in parentheses by mild symptoms vs. none / clinically significant symptoms vs. none.

FIGURE 1.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier Plots for Agitation and Severe Dementia (left plot) and for Agitation and Death (right plot).

Additional models were constructed controlling for psychotropic medication use (data not shown). Analyses were run for any antidepressant use (with separate analysis for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use), any antipsychotic use (with separate analyses for first generation antipsychotic and second generation antipsychotic use), and benzodiazepine use. Medication use was consistently not significant and there was no appreciable change in the results (i.e. the same predictors were predictive).

Discussion

In this population-based study of individuals with incident Alzheimer’s dementia, psychosis, agitation/aggression, and clinically significant neuropsychiatric symptoms were predictive of earlier progression to severe dementia and death. Affective neuropsychiatric symptoms and mild neuropsychiatric symptoms were associated with earlier death, but not earlier progression to severe dementia. These results expand on the analyses performed by Rabins et al. (5), in which women, those with less than high school education, participants with at least one clinically significant neuropsychiatric inventory domain, and the youngest or oldest age-of-onset cohorts progressed more rapidly to severe dementia. Age of onset showed a nonlinear relationship for time to severe Alzheimer’s dementia and a linear association with time to death. Global Medical Health Rating was not associated with time to severe Alzheimer’s dementia, but was associated with time to death and those with poor/fair scores had 1.6 times the death hazard compared to good/excellent (neuropsychiatric symptom results were not affected significantly by this).

In other samples, psychosis was shown to be predictive of progression to nursing home care, but not mortality, in Alzheimer’s dementia patients (4). In addition, behavioral disturbance has been associated with faster cognitive decline over 24 weeks among untreated patients (3). In this study, early agitation/aggression was a robust predictor of both accelerated progression and mortality. Other studies have commented on an apathy syndrome in Alzheimer’s disease as predictive of increased mortality (17). In this study, apathy was not predictive of accelerated mortality or progression to severe Alzheimer’s dementia. The treatment of specific neuropsychiatric symptoms in early dementia should be examined for its potential to delay time to severe dementia or death.

Although the causal nature of these predictive associations is not known, several possibilities exist. First of all, it is possible that a confounder exists that is not being measured in this study. Or perhaps, localized pathology of brain regions associated with agitation/aggression or psychosis occurs in more aggressive forms of Alzheimer’s dementia. Alternatively, the presence of these neuropsychiatric symptoms may influence the care environment in some way that in turn affects progression. For example, one may speculate that the presence of psychosis or agitation/aggression may lead to behaviors, situations, and relationships that are more conducive to worsening of disease. Affective symptoms could lead to similar modification. Although not evident in this study, it is also possible that the treatment of these symptoms with anti-psychotic medication increased mortality, as these drugs are associated with a 1.5–1.7 fold mortality increase in randomized trials and large scale cohort studies(18). The present study did not show a modification in progression based on medication use of any kind.

Limitations of this study include the lack of incident cases of age <65 years, small number of cases with severe Alzheimer’s dementia, and the homogeneity of the population (low rates of alcohol and illicit substance abuse and low representation of nonwhites). In general, the fact that this is a one time look at the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms based on frequency scores on the neuropsychiatric inventory without including severity scores or longitudinal measures of behavioral burden over the course from diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia to study endpoint is a limitation of the study. Lastly, it is a limitation that there was not a delirium screen included in the assessment as there is a very high risk of delirium in advancing dementia, and psychosis/agitation are known manifestations of delirium (19). A formal delirium assessment method, such as the confusion assessment method (CAM) (20), might identify undetected delirium and therefore subgroups at risk.

Strengths of the study include its epidemiologic sampling frame; high participation rate; its prospective, longitudinal data collection; and the use of state-of-the-art clinical diagnostic assessments of Alzheimer’s dementia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This research was supported by the Cache County Memory Study, Dementia Progression Study, and the Joseph and Kathleen Bryan ADRC: R01AG11380, R01AG21136, R01AG18712.

Authors have no conflicts of interest unless listed: Dr. Lyketsos receives grant support (research or CME) from NIMH, NIA, Associated Jewish Federation of Baltimore, Weinberg Foundation, Forest, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Eisai, Pfizer, Astra-Zeneca, Lilly, Ortho-McNeil, Bristol-Myers, Novartis, National Football League, Elan, Functional Neuromodulation; is a consultant/advisor to Astra-Zeneca, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Eisai, Novartis, Forest, Supernus, Adlyfe, Takeda, Wyeth, Lundbeck, Merz, Lilly, Pfizer, Genentech, Elan, NFL Players Association, NFL Benefits Office, Avanir, Zinfandel, BMS, Abvie, Janssen, Orion; and has received honorarium or travel support from Pfizer, Forest, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Health Monitor

Footnotes

Previous Presentation: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC), Vancouver, British Columbia, July 14–19, 2012; American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP) Conference, Orlando, Florida, March 14–17, 2014.

References

- 1.Rabins P, Lyketsos C, Steele C. Practical Dementia Care. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer's Association. 2012 Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez OL, Schwam E, Cummings J, Gauthier S, Jones R, Wilkinson D, Waldemar G, Zhang R, Schindler R. Predicting cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease: an integrated analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2010 Nov;6(6):431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stern Y, Tang MX, Albert MS, Brandt J, Jacobs DM, Bell K, Marder K, Sano M, Devanand D, Albert SM, Bylsma F, Tsai WY. Predicting time to nursing home care and death in individuals with Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 1997 Mar 12;277(10):806–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabins PV, Schwartz S, Black BS, Corcoran C, Fauth E, Mielke M, Christensen J, Lyketsos C, Tschanz J. Predictors of progression to severe Alzheimer's disease in an incidence sample. Alzheimers Dement. 2013 Mar;9(2):204–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Storandt M, Grant EA, Miller JP, Morris JC. Rates of progression in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2002 Oct 8;59(7):1034–1041. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.7.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breitner JC, Wyse BW, Anthony JC, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Steffens DC, Norton MC, Tschanz JT, Plassman BL, Meyer MR, Skoog I, Khachaturian A. APOE-epsilon4 count predicts age when prevalence of AD increases, then declines: the Cache County Study. Neurology. 1999 Jul 22;53(2):321–331. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyketsos CG, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Steffens DC, Breitner JC. Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000 May;157(5):708–714. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyketsos CG, Colenda CC, Beck C, Blank K, Doraiswamy MP, Kalunian DA, Yaffe K Task Force of American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. Position statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006 Jul;14(7):561–572. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221334.65330.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984 Jul;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tschanz JT, Corcoran CD, Schwartz S, Treiber K, Green RC, Norton MC, Mielke MM, Piercy K, Steinberg M, Rabins PV, Leoutsakos JM, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Breitner JC, Lyketsos CG. Progression of cognitive, functional, and neuropsychiatric symptom domains in a population cohort with Alzheimer dementia: the Cache County Dementia Progression study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011 Jun;19(6):532–542. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181faec23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982 Jun;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cummings JL. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology. 1997 May;48(5) Suppl 6:S10–S16. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5_suppl_6.10s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyketsos CG, Galik E, Steele C, Steinberg M, Rosenblatt A, Warren A, Sheppard JM, Baker A, Brandt J. The General Medical Health Rating: a bedside global rating of medical comorbidity in patients with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999 Apr;47(4):487–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb07245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters ME, Rosenberg PB, Steinberg M, Norton MC, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Hayden KM, Breitner J, Tschanz JT, Lyketsos CG Cache County Investigators. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms as Risk Factors for Progression From CIND to Dementia: The Cache County Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013 Feb 6; doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vilalta-Franch J, Calvo-Perxas L, Garre-Olmo J, Turro-Garriga O, Lopez-Pousa S. Apathy syndrome in Alzheimer's disease epidemiology: prevalence, incidence, persistence, and risk and mortality factors. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(2):535–543. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg M, Lyketsos CG. Atypical antipsychotic use in patients with dementia: managing safety concerns. Am J Psychiatry. 2012 Sep;169(9):900–906. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF, Kalisvaart KJ, Eikelenboom P, van Gool WA. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010 Jul 28;304(4):443–451. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990 Dec;15113(12):941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.