Abstract

Flexor tendons (FT) in the hand provide near frictionless gliding to facilitate hand function. Upon injury and surgical repair, satisfactory healing is hampered by fibrous adhesions between the tendon and synovial sheath. In the present study we used antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), specifically targeted to components of Tgf-β signaling, including Tgf-β1, Smad3 and Ctgf, to test the hypothesis that local delivery of ASOs and suppression of Tgf-β1 signaling would enhance murine FT healing by suppressing adhesion formation while maintaining strength. ASOs were injected in to the FT repair site at 2, 6 and 12 days post-surgery. ASO treatment suppressed target gene expression through 21 days. Treatment with Tgf-β1, Smad3 or Ctgf ASOs resulted in significant improvement in tendon gliding function at 14 and 21 days, relative to control. Consistent with a decrease in adhesions, Col3a1 expression was significantly decreased in Tgf-β1, Smad3 and Ctgf ASO treated tendons relative to control. Smad3 ASO treatment enhanced the max load at failure of healing tendons at 14 days, relative to control. Taken together, these data support the use of ASO treatment to improve FT repair, and suggest that modulation of the Tgf-β1 signaling pathway can reduce adhesions while maintaining the strength of the repair.

Keywords: Flexor tendon healing, Antisense oligonucleotides, Smad3, Ctgf, Tgf-β1

Introduction

Post-surgical adhesion formation is a significant clinical challenge following flexor tendon (FT) repair. Up to 30–40% of primary FT repairs exhibit unsatisfactory healing due to adhesion formation [1]. Fibrous adhesions between the tendon and synovial sheath disrupt the near frictionless gliding of the FT that is required for digit range of motion, and can impair the function of the entire hand. Although improvements in surgical techniques and new physical therapy protocols have dramatically improved FT repair outcomes [2, 3], there remains an unmet need to augment the healing process. More recently, biological approaches have emerged as potential approach to enhance FT healing and reduce adhesion formation, including delivery or inhibition of growth factors [4–6], with Transforming Growth Factor β (Tgf-β) signaling being one such candidate [5, 7].

Tgf-β signaling is causally associated with scar formation during healing in several tissues [8, 9], and is strongly correlated with pathological fibrosis during wound healing [10]. The Tgf-β pathway promotes scar formation through several mechanisms including stimulation of fibroblast proliferation and migration, synthesis of ECM components, and altered tissue remodeling through the regulation of Matrix metalloproteinases [11, 12]. In tendon cells, Tgf-β alters the balance away from tissue remodeling, a key step in the resolution of adhesions, and toward extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, potentially enhancing the scar formation response during tendon healing. Suppression of Tgf-β signaling has shown promise in enhancing tendon repair with respect to adhesion formation; digit range of motion (ROM) is increased using Tgf-β inhibitors [13, 14], while neutralizing antibodies against Tgf-β decreased adhesion formation during FT healing [5, 15, 16]. Given the therapeutic implications of its inhibition, the Tgf-β pathway is an attractive target to control scarring and adhesions following tendon injury.

Canonical Tgf-β signaling occurs via ligand binding to the TGF-β type II receptor, phosphorylation of Smad2/3, and activation of transcription of Tgf-β target genes via Smad2/3/4 [17]. Smad3 signaling modulates gene transcription related to ECM deposition [18], inflammation [19], and proliferation [20]. Smad3 deficient mice demonstrate resistance to scar formation in several models of fibrosis [21, 22]. We have previously demonstrated that FTs from Smad3−/− mice heal with fewer adhesions, decreased expression of ECM components, and increased Mmp expression. However, these improvements in gliding function come at the expense of the strength of the repair, with Smad3−/− repairs significantly weaker than wild type (WT) [7].

In addition to modulating Smad3 expression, Tgf-β signaling can be regulated by downstream signaling molecules. Connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf, Ccn2) is a matricellular protein that is implicated in pathological fibrosis [23, 24], while antisense-mediated suppression of Ctgf decreases hypertrophic scarring during dermal wound healing [25]. Taken together, there is a clear role for Tgf-β signaling in pathologic scar formation, with inhibition of specific signaling components, including Smad3 and Ctgf, being a feasible approach to reduce scar and adhesion formation during the healing process.

To move towards a more translational approach to enhance FT repair we have used antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) as a means to suppress Tgf-β signaling during healing. ASOs are single-stranded, modified oligonucleotides that bind specifically to the mRNA of interest, resulting in down-regulation of the protein. In the present study we have used ASOs against Tgf-β1, Smad3, and Ctgf to test the hypothesis that suppression of Tgf-β signaling results in attenuated scar formation during FT healing.

Methods

Flexor Tendon Repair and Treatment

All animal procedures were approved by the University Committee on Animal Research (UCAR). Eight-week-old male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were divided randomly into four treatment groups: ASO Control (scrambled oligonucleotide), Smad3 ASO, Tgf-β1 ASO, or Ctgf ASO. In the hind paw, the flexor digitorum longus (FDL) tendon was transected at the mid-paw and repaired with 8-0 nylon sutures in a modified Kessler pattern [26]. ASO treatments were delivered on post-operative days 2, 6 and 12 by local injection to the repair site using a micro-syringe. Tendons were harvested on post-repair days 3, 7, 10, 14, and 21 for real-time RT-PCR (n=4 mice per treatment per time point), histological analysis (n=4 mice per treatment per time point), and adhesion and biomechanical testing (n=6 mice per treatment per time point).

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs)

Twenty-mer phosphorothioate oligonucleotides to Smad3, Tgf-β1, and Ctgf containing 2′-O-methoxy-ethyl modifications were used for all experiments. In addition, a scrambled mismatch control twenty-mer containing a random mix of all four bases was used as a control. For in vivo use, 300μg of ASO was injected directly into the tendon repair site. To define the localization pattern of ASOs injected in to the hind paw, 100μl of black ink (Bradley Products, Bloomington, MN) was separately injected through the skin and remained localized to the hind paw (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Black ink was injected into the hind paw to evaluate the distribution of locally injected ASOs. (B) Repaired, ASO treated tendons were harvested on post-repair day 21. mRNA expression of Smad3, TgfB1, and Ctgf following gene-specific ASO treatment relative to expression in ASO control treated repairs. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *, **, and *** indicate significant differences of p<0.05, p<0.01, and p<0.001, respectively, between targeted ASO and ASO control.

RNA extraction and Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from individual FDL tendons as previously described [26]. In addition to murine specific primers for target genes (Smad3, Tgfβ1, Ctgf), changes in matrix deposition (Col3a1, Col1a1), tenogenic genes (Scx, Tnmd) and tissue remodeling (Mmp9) were assessed. mRNA expression was normalized to β-actin, and expression in ASO control tendons at day three post-surgery.

Histology

The hind limb containing the repaired FDL tendon was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 hours at 4°C, such that the foot was fixed at a 90° angle relative to the tibia. Fixed tissues were washed in PBS and decalcified for 21 days in 14% EDTA. The tissues were then processed and embedded in paraffin. Longitudinal 3 μm sections were stained with Alcian Blue/Hematoxylin/Orange G and assessed qualitatively.

Immunohistochemistry

Five-micron sections were probed with phospho-Smad3 (Abcam #ab52903, 1:100) or Ctgf (Santa Cruz #sc-13100, 1:100) primary antibodies, followed by a goat-anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Staining was visualized with DAB chromogen and counterstained with Hematoxylin (Ctgf) or Methyl Green (Smad3) and assessed qualitatively.

MTP Joint flexion and biomechanical testing

Following harvest of the hind limbs, samples were rigidly fixed in a custom testing apparatus to determine MTP ROM [26, 27]. The proximal end of the FDL tendon was isolated and loaded with incremental static weights up to 19g, while digital images were taken at each increment. The MTP ROM corresponds to the MTP Joint angle at the maximum applied load of 19g. Un-injured control tendons reach complete flexion (~73°) when 19g is applied. The metatarsophalangeal (MTP) range of motion (ROM) was measured using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) by two blinded independent observers [27].

Following MTP ROM testing, tendon biomechanics were tested as previously described using the 8841 Instron DynaMight axial servo-hydraulic testing system (Instron Industrial Products, Norwood, MA) [26–28].

Statistical Analysis

Results are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was tested via two-way ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post hoc multiple comparisons with significance set at p<0.05.

Results

ASOs efficiently knock-down target gene expression in tendon tissue

Relative to ASO control, mRNA expression of all three genes was significantly decreased 21 days after repair (Figure 1B); Smad3 was decreased 57% (p<0.01), Ctgf was decreased 30% (p<0.001), Tgf-β1 was decreased by 50%, (p<0.05) suggesting that each ASO effectively decreases expression of the target gene.

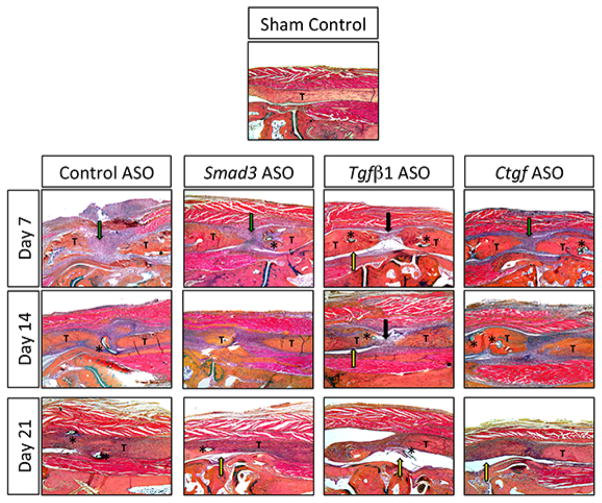

ASO Treatment Enhances Remodeling Between the Tendon and Surrounding Tissue

The control ASO treated group exhibited a robust granulation tissue response at day seven (green arrow), to bridge the gap at the injury site, with a less robust response in Smad3 ASO (green arrow) and Ctgf ASO (green arrow) treated repairs. In contrast, Tgf-β ASO treated repairs demonstrated a paucity of granulation tissue (black arrow) along with space between the tendon and surrounding tissue (yellow arrow).

On day 14, the ASO-control treated tendons were more closely approximated and the granulation response was less extensive than on day seven. Further, the tendon-healing site was becoming better organized but the scar tended to merge with the surrounding soft tissues. Similar morphologic changes were observed in Smad3 ASO and Ctgf ASO treated repairs but with a reduced granulation tissue response, and decreases merging with the native tendon. Consistent with its morphology on day seven, Tgf-β ASO treated repairs continued to have less of a granulation tissue response after 14 days.

By day 21, the control ASO treated repairs exhibited progressive healing with the original tendon tissue bridged with granulation tissue that was more organized, demonstrating remodeling of the repair tissue. However, there was still abundant merging of the tendon repair site with the surrounding tissue. In contrast, a clear space exists between the regenerating tendons and surrounding tissue in all three ASO treated groups (yellow arrows), suggesting reduced adhesions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A representative section of the uninjured FDL tendon is shown for comparison (Sham Control, top image). In each section, “T” is used to label the proximal and distal ends of the tendon around the repair site. An asterisk (*) is placed adjacent to the suture material when it appears in the representative section. Robust granulation tissue response (green arrow), paucity of granulation tissue (black arrow), and space between the tendon and surrounding tissue (yellow area) are indicated by colored arrows. Sections were stained with alcian blue hematoxylin/orange G eosin (100× magnification).

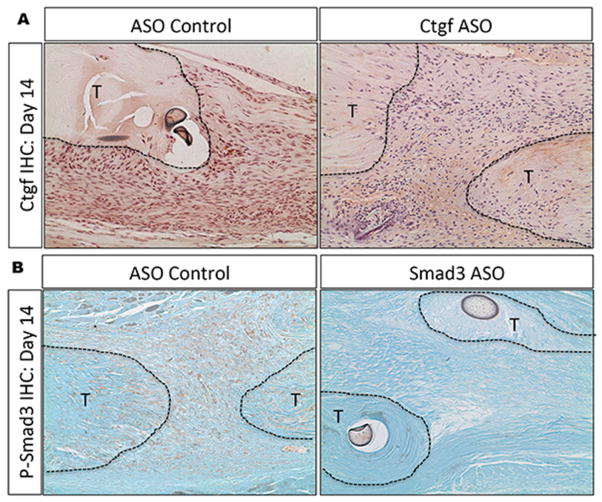

ASOs decrease target protein expression during FT healing

At day 14, abundant Ctgf positive cells were observed in the granulation tissue of control ASO treated tendons, with a few Ctgf expressing cells in the native tendon. In contrast, an appreciable decrease in Ctgf positive cells are observed in the granulation tissue and native tendon of Ctgf ASO treated tendons, relative to ASO control (Figure 3A). Phospho-Smad3 expressing cells were located in both the granulation tissue and native tendon at 14 days in control ASO treated tendons. In Smad3 ASO treated tendons, the abundance of p-Smad3 positive cells in the native tendon and granulation tissue was markedly reduced, relative to control ASO treated tendons (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Ctgf is expressed in the granulation tissue of ASO control treated tendons at 14 days, while very few Ctgf+ cells are observed in the granulation tissue or native tendon of Ctgf ASO treated tendons. (B) Phosph-Smad3 expression is observed in native tendon and granulation tissue in ASO control treated repairs at day 14, while a paucity of p-Smad3 cells are observed in Smad3 ASO treated tendons.

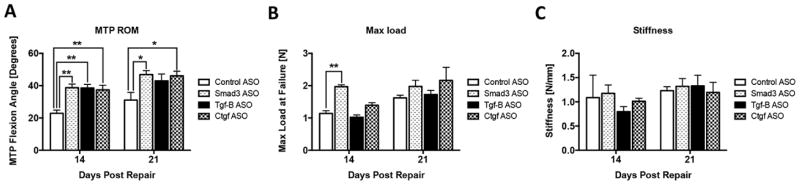

Gliding Function is Improved By ASO Treatment

On day 14, all three ASO treated repairs showed a significant increase in MTP ROM relative to control ASO (Smad3: +69%; Tgf-β: +68%; Ctgf: +63%)(p<0.01) (Figure 4A). This significance was maintained on post-repair day 21 in the Smad3 ASO (+51%) and Ctgf ASO (+48%)(p<0.05) treated repairs. MTP ROM was increased Tgf-β ASO treated repairs, however the increase relative to control ASO was not statistically significant (+38%, p=0.09).

Figure 4.

(A) Metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint range of motion (ROM), (B) Maximum load at failure, and (C) stiffness in ASO treated and control ASO treated FDL tendons on post-repair days 14 and 21. Data is presented as mean ± SEM. * and ** indicate significant differences of p<0.05 and, p<0.01 between ASO treated and control ASO.

ASO Treated Repairs Maintain Strength and Stiffness

Smad3 ASO treated repairs had a significant increase in maximum load at failure, relative to control ASO at day 14 (1.97N ± 0.14 vs. 1.14N ± 0.20, p<0.05) (Figure 4B). There were no significant differences in maximum load at failure between the Tgfb and Ctgf ASO treatment groups and control ASO at day 14, and there were no significant differences in strength between the treatment and control ASO groups 21 days post-repair. This suggests that ASO treatment does not impair the strength of repair, and, in the case of Smad3 ASO treatment, may improve the early strength of repairs.

The stiffness was not significantly different between ASO treated and control ASO repairs at either 14 or 21 days post-repair (Figure 4C), suggesting that ASO treatment does not compromise the biomechanical properties of the healing tendon.

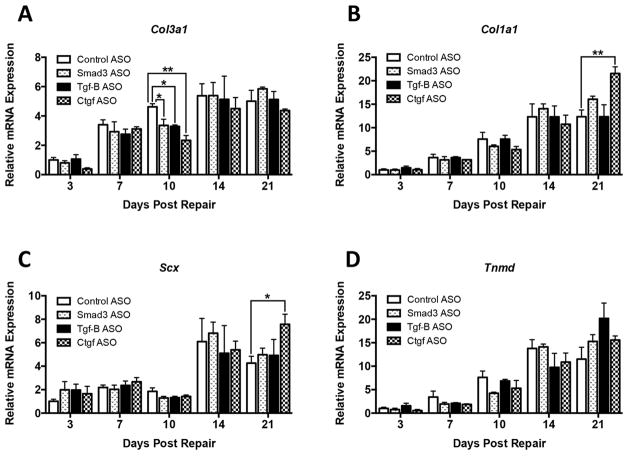

Attenuating Tgf-β Signaling Alters ECM and Tenogenic Gene Expression During Healing

Significant decreases in Col3a1 mRNA expression were observed in the ASO treated groups relative to control ASO on day 10; Smad3 (−27%, p<0.05), Tgf-β1 (−29%, p<0.05), and Ctgf (−50%, p<0.01) (Figure 5A). Col3a1 expression remained elevated over day three levels through day 21, however, expression was not significantly different between treatment groups and control ASO at any other time points.

Figure 5.

Relative mRNA expression of (A) Col3a1, (B) Col1a1, (C) Scx, and (D) Tnmd in FDL tendon repair tissue on post-operative days 3, 7, 10, 14, and 21. Expression was normalized to βactin, and expression in control ASO repairs at day 3. Data is presented as mean ± SEM. * and ** indicate significant differences of p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively, between gene targeted ASO and control ASO.

Significant increases in Col1a1 were seen at 21 days in Ctgf ASO treated repairs relative to control ASO (+75%, p<0.01) (Figure 5B), suggesting an increase in the collagen profile associated with mature, remodeled tendons. In all groups, ASO treated and control ASO, Col1a1 expression increased from day three through day 21 (Figure 5B).

Scleraxis (Scx) is required for tendon formation [29], and regulates expression of Col1a1 and Tenomodulin (Tnmd) [30], while Tnmd can regulate tenocyte proliferation and collagen maturation [31]. Relative to control ASO, Scx expression on day 21 was significantly increased in Ctgf ASO treated repairs (+78%, p<0.05) (Figure 5C), consistent with increased expression of Col1a1 observed at the same time point (Figure 5B). No significant differences in Tnmd expression were seen between any of the treatment groups.

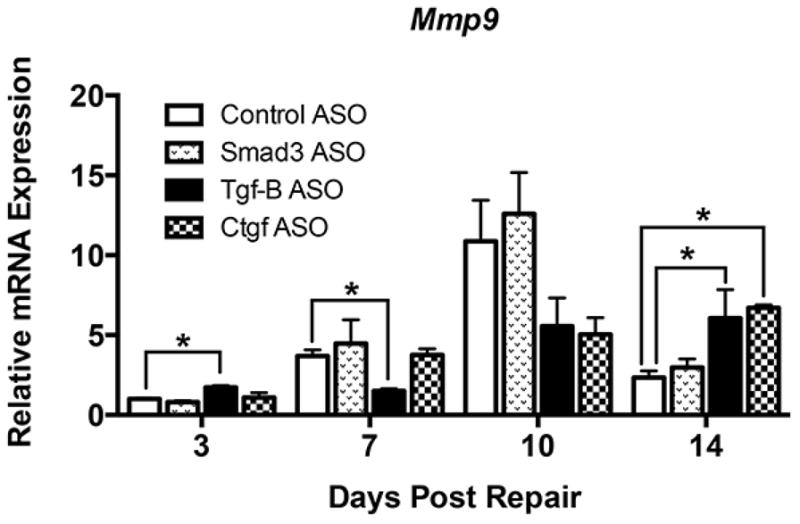

Tgf-β ASO Treatment Alters Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Expression During Healing

Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (Mmp9; Gelatinase B) expression increases during the early inflammatory response of murine FT healing [26], and is associated with catabolism of native collagen at the repair site [28]. Consistent with this, Mmp9 expression was significantly increased in control ASO treated repairs at day 10, relative to day three, with expression levels returning to those comparable to day three by day 14. Relative expression of Mmp9 was significantly increased at day three in Tgf-β ASO treated repairs compared to control ASO (+73%, p<0.05) (Figure 6). By day seven, repairs treated with Tgf-β ASO showed a significant decrease in Mmp9 expression relative to control ASO (−59%, p<0.05). Increases in Mmp9 expression were observed 14 days in both Tgf-β ASO (+159%, p<0.05) and Ctgf ASO treated groups (+188%, p<0.05), relative to control ASO. Smad3 ASO treatment resulted in elevated Mmp9 expression at day 10, though Smad3 ASO repairs were not significantly different than control ASO treated repairs at any time.

Figure 6.

Relative mRNA expression of Mmp9 in FDL tendons on post-operative days 3, 7, 10, and 14. Expression was normalized to β-actin, and expression in control ASO repairs at day 3. Data is presented as mean ± SEM. * and ** indicate significant differences of p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively, between gene targeted ASO and control ASO.

Discussion

In the present study we have demonstrated that local injection of Tgf-β1, Smad3, and Ctgf ASO’s results in sustained down-regulation of target gene and protein expression during FT repair. Disrupting Tgf-β signaling significantly attenuates adhesion formation without further compromising the biomechanical properties of the healing tendon.

Tgf-β is crucial for fibroblast proliferation [32], indeed, Tgf-β ASO treated tendons display a dramatic reduction in cellularity and granulation tissue at the repair site at seven and 14 days, relative to all other groups, likely accounting, in part, for the increase in MTP ROM observed in Tgf-β ASO treated tendons, relative to control ASO. This is consistent with previous studies in which direct inhibition of Tgf-β [5, 13–16] resulted in improved gliding function and ROM. In addition, Tgf-β ASO treated tendons had a significant reduction in Mmp9 expression, relative to control ASO at 7 and 10 days, likely resulting in decreased catabolism of native collagen and suppressing the granulation tissue response, consistent with Tgf-β mediated up-regulation of Mmp9 during fibrosis [33], although Mmp9 was increased in Tgf-β ASO treated tendons at day 14.

We have previously demonstrated that Smad3−/− mice heal with a significant decrease in adhesion formation, resulting in improved gliding function, relative to WT; however, Smad3−/− repairs are also significantly weaker than WT (only 42% of the strength of WT repairs at 21 days) [7]. In contrast, treatment with Smad3 ASO does not impair the biomechanics of the repair, while dramatically improving gliding function, suggesting that local, rather than systemic inhibition of Smad3 has potential therapeutic value. In addition while Smad3−/− mice have complete absence of gene expression, the reduction in gene expression in Smad3 ASO treated repairs is incomplete. Smad3 ASO treatment decreased Col3a1 expression at 10 days, consistent with decreased Col3a1 expression in Smad3−/− mice, supporting the concept that inhibition of Smad3 may decrease scarring by blunting ECM deposition. Moreover, un-injured Smad3−/− tendons are significantly weaker than WT littermates [7], indicating a potential role for Smad3 in normal tendon homeostasis. Recently, Berthet et al., have demonstrated that Smad3 is required for appropriate tendon development, and that Smad3−/− tendons have decreased Col1a1 and Tnmd [34], suggesting that Smad3 plays an important role in tendon ECM deposition and organization. Based on the consistent decrease in adhesion formation between Smad3−/− and Smad3 ASO treated mice, but the dramatic improvements in the biomechanical properties of Smad3 ASO treated mice, relative to Smad3−/− repairs, there is a clear advantage to ASO mediated inhibition of Smad3, resulting in targeted and inducible suppression of gene/protein expression, without the systemic and tendon homeostatic effects of gene deletion, however inducible, systemic inhibition of Smad3 may also be a feasible approach for future study.

Ctgf promotes fibroblast proliferation, ECM production, and formation of granulation tissue [23], and is required for the profibrotic effects of Tgf-β in several models of disease [23]. In tendon, Ctgf is expressed during early healing, coinciding with elevated levels of Tgf-β [35], and is elevated in an in vitro model of tendinopathy [36]. Here we show that Ctgf ASO treatment enhances MTP ROM, possibly due to decreased Mmp9 mediated collagen catabolism and subsequent ECM deposition, as more of the native tendon remains present after 21 days of healing.

While the present study validates the use of ASOs as a therapeutic approach to enhance FT healing by decreasing adhesion formation while maintaining the biomechanical properties, in the context of attenuated Tgf-β signaling, there are a number of limitations that must be considered. We have demonstrated that ASO treatment results in sustained decrease in target gene and protein expression through 21 days, however, we do not know how long this attenuation is maintained. While ASOs are generally quite sensitive to degradation in vivo, we have used 2′-O-methoxyethyl chemically modified ASOs, which are resistant to nuclease degradation in vivo [37]. In addition, we have focused on the early events of FT healing, since adhesion formation is associated with the early inflammatory events [38, 39]. However, given the relationship between Tgf-β signaling and Mmp activity, it will be particularly important going forward to understand the effects on long-term tissue remodeling.

Taken together, we have demonstrated that ASO mediated inhibition of both Tgf-β1 and Tgf-β1 signaling molecules decreases adhesion formation and improves gliding function following murine FT repair, while Smad3 ASO treatment also improves the early biomechanical properties of the healing tendon. Given that ASOs have been approved by the FDA [40, 41], and are in clinical trials[42, 43], there is a clear translational application of this technology to enhance the challenging problem of adhesion formation during FT healing.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Histology, Biochemistry and Molecular Imaging (HBMI) and Biomechanics and Multimodal Tissue Imaging (BMTI) cores for technical assistance. This work is supported by the Department of Defense (DOD) grant (W81XWH-09-PRORP-IDA) to RJO, and NIH/NIAMS R01AR056696 to HAA. MBG was supported by CTSA (TL1 TR000096) from NIH/NCATS. SK was supported by funding from the UR Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI). The HBMI and BMTI cores are supported by NIH/NIAMS P30 AR061307.

Footnotes

Author roles: Study design/data acquisition/analysis/interpretation: AEL, KY, MBG, SK, SS JHJ, HAA, RJO. Drafted the manuscript: AEL, KY, MBG, SK, RJO. Approved the manuscript: AEL, KY, MBG, SK, SS, JHJ, HAA, RJO.

References

- 1.Aydin A, Topalan M, Mezdegi A, et al. Single-stage flexor tendoplasty in the treatment of flexor tendon injuries. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2004;38(1):54–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osei DA, Stepan JG, Calfee RP, et al. The effect of suture caliber and number of core suture strands on zone II flexor tendon repair: a study in human cadavers. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(2):262–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang JB, Amadio PC, Boyer MI, et al. Current practice of primary flexor tendon repair: a global view. Hand Clin. 2013;29(2):179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basile P, Dadali T, Jacobson J, et al. Freeze-dried tendon allografts as tissue-engineering scaffolds for Gdf5 gene delivery. Mol Ther. 2008;16(3):466–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang J, Thunder R, Most D, et al. Studies in flexor tendon wound healing: neutralizing antibody to TGF-beta1 increases postoperative range of motion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(1):148–55. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200001000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomopoulos S, Das R, Silva MJ, et al. Enhanced flexor tendon healing through controlled delivery of PDGF-BB. J Orthop Res. 2009;27(9):1209–15. doi: 10.1002/jor.20875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katzel EB, Wolenski M, Loiselle AE, et al. Impact of Smad3 loss of function on scarring and adhesion formation during tendon healing. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(5):684–93. doi: 10.1002/jor.21235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez IE, Eickelberg O. The impact of TGF-beta on lung fibrosis: from targeting to biomarkers. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2012;9(3):111–6. doi: 10.1513/pats.201203-023AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeves WB, Andreoli TE. Transforming growth factor beta contributes to progressive diabetic nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(14):7667–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.7667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krummel TM, Michna BA, Thomas BL, et al. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) induces fibrosis in a fetal wound model. J Pediatr Surg. 1988;23(7):647–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(88)80638-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashiwagi K, Mochizuki Y, Yasunaga Y, et al. Effects of transforming growth factor-beta 1 on the early stages of healing of the Achilles tendon in a rat model. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2004;38(4):193–7. doi: 10.1080/02844310410029110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang G, Crawford RC, Wang JH. Proliferation and collagen production of human patellar tendon fibroblasts in response to cyclic uniaxial stretching in serum-free conditions. J Biomech. 2004;37(10):1543–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bates SJ, Morrow E, Zhang AY, et al. Mannose-6-phosphate, an inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta, improves range of motion after flexor tendon repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(11):2465–72. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiong Y, Zhang Z. Experimental studies on decorin in suppression of postoperative flexor tendon adhesion in rabbits. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2006;20(3):251–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukui N, Tashiro T, Hiraoka H, et al. Adhesion formation can be reduced by the suppression of transforming growth factor-beta1 activity. J Orthop Res. 2000;18(2):212–9. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jorgensen HG, McLellan SD, Crossan JF, Curtis AS. Neutralisation of TGF beta or binding of VLA-4 to fibronectin prevents rat tendon adhesion following transection. Cytokine. 2005;30(4):195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heldin CH, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P. TGF-beta signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature. 1997;390(6659):465–71. doi: 10.1038/37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arany PR, Flanders KC, Kobayashi T, et al. Smad3 deficiency alters key structural elements of the extracellular matrix and mechanotransduction of wound closure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(24):9250–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602473103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dennler S, Goumans MJ, ten Dijke P. Transforming growth factor beta signal transduction. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71(5):731–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moustakas A, Pardali K, Gaal A, Heldin CH. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling in regulation of cell growth and differentiation. Immunol Lett. 2002;82(1–2):85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flanders KC, Sullivan CD, Fujii M, et al. Mice lacking Smad3 are protected against cutaneous injury induced by ionizing radiation. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(3):1057–68. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64926-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujimoto M, Maezawa Y, Yokote K, et al. Mice lacking Smad3 are protected against streptozotocin-induced diabetic glomerulopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305(4):1002–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00885-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipson KE, Wong C, Teng Y, Spong S. CTGF is a central mediator of tissue remodeling and fibrosis and its inhibition can reverse the process of fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2012;5:S24. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-5-S1-S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponticos M, Holmes AM, Shi-wen X, et al. Pivotal role of connective tissue growth factor in lung fibrosis: MAPK-dependent transcriptional activation of type I collagen. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(7):2142–55. doi: 10.1002/art.24620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sisco M, Kryger ZB, O’Shaughnessy KD, et al. Antisense inhibition of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) mRNA limits hypertrophic scarring without affecting wound healing in vivo. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(5):661–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loiselle AE, Bragdon GA, Jacobson JA, et al. Remodeling of murine intrasynovial tendon adhesions following injury: MMP and neotendon gene expression. J Orthop Res. 2009;27(6):833–40. doi: 10.1002/jor.20769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasslund S, Jacobson JA, Dadali T, et al. Adhesions in a murine flexor tendon graft model: autograft versus allograft reconstruction. J Orthop Res. 2008;26(6):824–33. doi: 10.1002/jor.20531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loiselle AE, Frisch BJ, Wolenski M, et al. Bone marrow-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 is associated with fibrous adhesion formation after murine flexor tendon injury. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murchison ND, Price BA, Conner DA, et al. Regulation of tendon differentiation by scleraxis distinguishes force-transmitting tendons from muscle-anchoring tendons. Development. 2007 doi: 10.1242/dev.001933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alberton P, Popov C, Pragert M, et al. Conversion of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells into tendon progenitor cells by ectopic expression of scleraxis. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(6):846–58. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Docheva D, Hunziker EB, Fassler R, Brandau O. Tenomodulin is necessary for tenocyte proliferation and tendon maturation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(2):699–705. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.699-705.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anzano MA, Roberts AB, Smith JM, et al. Sarcoma growth factor from conditioned medium of virally transformed cells is composed of both type alpha and type beta transforming growth factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80(20):6264–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.20.6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramirez G, Hagood JS, Sanders Y, et al. Absence of Thy-1 results in TGF-beta induced MMP-9 expression and confers a profibrotic phenotype to human lung fibroblasts. Lab Invest. 2011;91(8):1206–18. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berthet E, Chen C, Butcher K, et al. Smad3 binds Scleraxis and Mohawk and regulates tendon matrix organization. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(9):1475–83. doi: 10.1002/jor.22382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen CH, Cao Y, Wu YF, et al. Tendon healing in vivo: gene expression and production of multiple growth factors in early tendon healing period. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(10):1834–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakama LH, King KB, Abrahamsson S, Rempel DM. VEGF, VEGFR-1, and CTGF cell densities in tendon are increased with cyclical loading: An in vivo tendinopathy model. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(3):393–400. doi: 10.1002/jor.20053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H, Cook J, Nickel J, et al. Reduction of liver Fas expression by an antisense oligonucleotide protects mice from fulminant hepatitis. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18(8):862–7. doi: 10.1038/78475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strickland JW. Flexor Tendon Injuries: I. Foundations of Treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3(1):44–54. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beredjiklian PK. Biologic aspects of flexor tendon laceration and repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(3):539–50. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200303000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Highleyman L. FDA approves fomivirsen, famciclovir, and Thalidomide. Food and Drug Administration. BETA. 1998:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tse MT. Regulatory watch: Antisense approval provides boost to the field. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(3):179–179. [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Deutekom JC, Janson AA, Ginjaar IB, et al. Local dystrophin restoration with antisense oligonucleotide PRO051. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(26):2677–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schimmer AD, Estey EH, Borthakur G, et al. Phase I/II trial of AEG35156 X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein antisense oligonucleotide combined with idarubicin and cytarabine in patients with relapsed or primary refractory acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4741–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.8172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]