Abstract

The VOICE Adherence Strengthening Program (VASP) was implemented in May 2011 to improve adherence counseling in VOICE (MTN-003), a multisite placebo-controlled trial of daily oral or vaginal tenofovir-based Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). Anonymous baseline (N = 82) and final follow-up (N = 75) surveys were administered to counselors and pharmacists at 15 VOICE sites, and baseline (N = 18) and final (N = 26) qualitative in-depth interviews were conducted with purposively selected counseling staff at 13 VOICE sites. Qualitative interviews with VOICE participants (N = 38) were also analyzed for segments related to counseling. Behavioral and biological measures of product use collected in the 6 months prior to VASP implementation were compared to those collected during the 6 months following implementation. Results show that the majority of staff preferred VASP and thought that participants preferred VASP over the previous education and counseling strategy, although there was no evidence to suggest that participants noticed modifications in the counseling approach. No meaningful changes were observed in pre/post levels of reported use or drug detection. Interpretation of results is complicated by mid-trial implementation of VASP and its proximity to early closure of oral and vaginal tenofovir study arms because of futility.

Keywords: PrEP, Microbicides, Adherence, Intervention, Counseling staff, HIV prevention trial

Introduction

Heterogeneity of results across effectiveness trials of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) have in large part been attributed to suboptimal adherence, highlighting the critical need for enhanced approaches to measure and support product use in clinical trials [1, 2]. Several HIV prevention trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of oral or vaginal tenofovir-based PrEP, with greater protection observed among those with higher product adherence [3–7]. In contrast, two large trials among women, FemPrEP and VOICE (Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic), were unable to demonstrate any effect in the context of low product use [8, 9]. Although these findings demonstrate that adequate protection hinges on high product adherence [10], it is less evident how to achieve effective use of PrEP in clinical trials or real-world settings [11–13]. Experiences from completed trials may inform the development of adherence support strategies going forward, even as further research is needed to improve adherence within PrEP trials.

VOICE was a Phase IIb placebo-controlled trial of daily 1 % vaginal tenofovir (TFV) gel, oral tenofovir (TDF) tablets, and oral tenofovir/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC, Truvada®) tablets for the prevention of HIV infection among sexually active, HIV-uninfected women in South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. Final analyses of the trial indicate that products were not effective. However, substantial rates of product non-use limit efficacy and safety conclusions [14].

As previously described, mid-trial, the VOICE Adherence Working Group examined the product adherence counseling and support component of the VOICE study and identified procedural changes to encourage accuracy in reporting as well as strategies to promote product use. A revised approach was developed and implemented in May 2011—the VOICE Adherence Strengthening Program (VASP). VASP was based on Next-Step-Counseling and other participant-centered approaches for behavior change [12, 15]. Its goal was to create a supportive environment where participants could share their experience using the product with the counselors, while recognizing that product use is ultimately a choice.

The ACME (Adherence Counseling Monitoring and Evaluation) project collected data concerning the perception and experience of VOICE staff providing product adherence counseling1 both before and after the implementation of VASP. This paper presents findings from quantitative surveys and qualitative individual in-depth interviews (IDIs) with VOICE counseling staff prior to VASP implementation (baseline) and at final follow-up. In addition, we report on qualitative interviews as well as self-reported adherence among VOICE participants, and plasma tenofovir drug detection before and after VASP implementation, among a random subset of VOICE participants in the active study arms for whom plasma drug levels are available, in order to explore whether implementation of VASP had an effect on adherence.

Methods

Study Populations

Staff

The primary population for the ACME evaluation was counseling staff at all 15 VOICE sites, which included an estimated 130 counselors, nurse counselors, and pharmacists, at the time of the baseline assessment in February 2011. All staff involved in participant product adherence counseling were invited to complete an anonymous web-based survey at baseline (N = 82) prior to VASP training and at final follow-up (N = 75) in May 2012, just prior to completing the VOICE study. Baseline (N = 18) and follow-up (N = 26) qualitative IDIs were conducted with purposively selected staff at 13 sites. ACME data collection and analyses were conducted by San Francisco-based RTI/WGHI staff.

VOICE Participants

From September 2009 to August 2012, 5,029 HIV-negative, sexually active, non-pregnant women on effective contraception and aged 18-45 were enrolled and followed monthly for up to 36 months at 15 sites in South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe as part of the VOICE trial [9]. Participants were equally randomized to one of five study groups: oral TDF (300 mg); oral TDF/FTC (300/200 mg); oral placebo; vaginal TFV 1 % gel; or vaginal placebo gel. In September 2011, the NIAID Prevention Data Safety Monitory Board (DSMB) providing oversight for the VOICE trial recommended that the oral TDF arm be discontinued for futility [16]. In November 2011, a similar determination was made for TFV gel, and the active and placebo gel arms were also discontinued and exited from the study [17]. Women assigned to the Truvada or oral placebo arms continued participation until planned study end in August 2012. A subset of VOICE participants assigned to the active study product arms was randomly selected for analysis of plasma TFV concentrations at quarterly visits (N = 488). This random pharmacokinetic [PK] cohort allowed assessment of product use with a biological measure [14].

VOICE-C Participants and Methods

As previously described, VOICE-C was a qualitative, exploratory ancillary study implemented between July 2010 and August 2012 at the Wits-RHI Johannesburg site in South Africa, concurrent with the VOICE trial [18]. In VOICE-C, the VOICE participants were randomly preselected and randomly assigned to several qualitative interview modalities, including an in-depth interview (IDI; N = 41), using a guide that included questions about adherence counseling. For this study, we analyzed 38 IDI transcripts that had coded segments with “counseling-related” content.

Counseling Intervention: VASP

A total of six 1-day VASP trainings were held locally in March to April 2011, to train all counseling staff (and site leadership when possible) from the 15 VOICE sites, with a range of 1–3 sites per training. The trainings included basic and advanced client-centered counseling skills on each of the steps included in VASP through a combination of didactic, interactive, role play, and experiential-based learning (see [12]). The VASP approach was implemented in May 2011, approximately 20 months after VOICE study initiation and 4 months prior to the oral TDF arm discontinuation. We used a mentoring approach to follow up with site counseling staff during monthly calls to keep the calls small and interactive. Mentors were asked to meet regularly with their site's counseling staff to debrief and discuss counseling issues. In addition, 5 months after VASP implementation, a booster training was conducted with all counseling staff at the sites [12]. Several aspects of the original adherence support program (ASP) were retained and bolstered to create VASP, while elements that were thought to be counterproductive were modified or eliminated (Table 1; and [12]). The most significant changes were eliminating the counseling scripts that were tied to estimated adherence levels and eliminating product reconciliation between the pharmacy and self-report during the counseling session. Counseling staff roles also shifted with the implementation of VASP. Pharmacists focused on product education and accountability (including assessing adherence based on returned product counts) and other counseling staff (counselors and nurse counselors) focused solely on adherence counseling. This change was made to fully separate adherence assessment from adherence counseling and support and to promote greater openness and honesty in both areas. The separation of assessment and counseling varied among sites, where some sites eliminated participant-pharmacist interactions entirely.

Table 1.

Key revisions to adherence counseling approach in VOICE

| Original adherence support program (ASP) | VOICE adherence strengthening program (VASP) |

|---|---|

| Used product count from pharmacists to inform the counseling session; reconciled product count and self-reported adherence | Counselors will NOT review product count prior to counseling session or probe about discrepancies in product count versus self-report |

| Asked the participant how often she had been able to use the product and then based counseling on reported level of adherence | Counseling will focus on participant's experiences using the product, and what makes using product easier or harder, regardless of how much she used it |

| Adherence plan/strategies based on overcoming barriers to product use | Adherence plan/strategies based on addressing adherence-related needs |

| Used reported adherence (none, some, or all of the time) to determine the focus of the session | All sessions will follow the same 8 steps, regardless of how much the participant has been using the study product |

| Reinforcement of product use instructions (10 key messages) by the adherence counselor | Product use instructions (10 key messages) removed from the counseling session and instead reviewed by other staff as needed |

| Positive reinforcement of good adherence | Maintain a neutral counseling approach |

| Goals focused on perfect adherence | Goals focused on making product use manageable |

Measures

Staff Experience and Perception

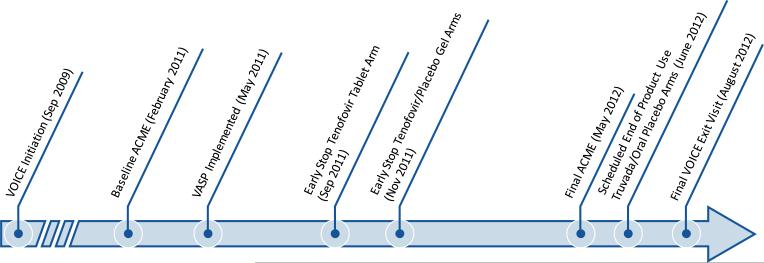

Timing of the staff baseline and follow-up assessments relative to VASP implementation, early stopping of study arms per DSMB recommendations and end of study follow-up are illustrated in Fig. 1. Baseline and final follow-up assessments included a quantitative anonymous web-based survey, with close-ended and open-ended questions, as well as IDIs with adherence counseling staff, conducted by interviewers not affiliated with the VOICE team. The IDIs were collected confidentially, and by design were not linked to the anonymous surveys. No identifying information was collected during the IDIs and the analysis team did not include any of the qualitative interviewers to preserve anonymity. Questions in the web-based survey explored staff perceptions about the goals of product adherence counseling, usefulness, and attitudes toward the adherence support approach, as well as stress and support experienced in their counseling roles; IDI discussion topics were similar and complemented the surveys. IDIs were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed for key themes.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of VOICE, VASP implementation and ACME assessments (not to scale) ACME Adherence Counseling Monitoring and Evaluation project, VASP VOICE Adherence Strengthening Program

Product Adherence Assessments

Behavioral measures of product use amongst VOICE participants included [1] clinic product counts (CPC; ratio of returned unused pills, or unused gel applicators over expected days of use) conducted monthly; and [2] pictorial audio-computer assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) frequency of product use, dichotomized as zero versus ≥ 1dose taken in the past 7 days, conducted quarterly. Other measures collected monthly by face-to-face interviews are not presented, as they yielded virtually the same findings.

Plasma Drug Levels

Plasma tenofovir detection was conducted in a subset of participants in the active product random PK cohort, as described previously [9]. Briefly, tenofovir plasma concentration <0.3 ng/mL (the lower limit of quantification, LLOQ) or undetectable tenofovir level was defined as biological non-use [19, 20].

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of Staff Attitudes and Experience

Quantitative data were summarized across all sites and stratified by staff cadre (counselor or pharmacist) because of their different roles in adherence counseling. Additional analyses, comparing baseline and final surveys were conducted on staff attitudes and experiences with ASP/VASP, among the subset of 39 participants who could be matched between the baseline and endline surveys, in order to confirm that changes observed were due to actual shifts in behavior/attitudes rather than to differences in the samples; findings are essentially the same as those of the unmatched analyses, and thus are not presented here.

Qualitative data from the open-ended questions in the staff surveys and the IDIs of staff and VOICE-C participants were coded by two analysts, not affiliated with VOICE, with average inter-coder reliability of ≥80 %. Study-specific codebooks were developed for the ACME as well as for the VOICE-C qualitative data [18]. Open-ended responses to the staff baseline and final survey questions were categorized based on the ACME codebook. Wherever possible, qualitative data were quantified to illustrate the frequency of themes and to compare themes by staff role. Matched interview pairs were used to assess change over time on two key themes: [1] openness/honesty of participants as perceived by staff; and [2] counseling approach. For VOICE-C data, the coded reports were analyzed based on date of VOICE participants’ IDIs (11 IDIs conducted pre-VASP and 27 IDIs conducted post-VASP) and focused on two key themes: [1] perceived changes in counseling approach, and [2] experiences with adherence counseling and counseling staff. Direct quotes from IDIs and open-ended survey responses are used to illustrate specific themes (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Qualitative quotes with VOICE counselors; pharmacists and participants

| Theme | Representative quotes |

|---|---|

| Counseling role, Successful session | [A successful session is when]...you've made them feel at home with you; they're talking with ease and they're giving you all of the experiences they have had... and you find that they are also willing to re-strategize on how they're going to take the product and you set a goal...I normally want to address a woman in whole, in total...They know you're not only concerned about [product use]..if I attend to them in total and try to address their issues it will help me, and I'm sure they'll take also the product because they know...I'm concerned about them in total. (Counselor #02) |

| Diminished role of pharmacists | I feel like [VASP] makes it to look like we don't care the way we used to care before...I feel like we are not getting more details to the way we were before. And, if others were happy to say something in the pharmacy or with a pharmacist staff, so, if now we don't interact like that... there are other things that might go unnoticed because maybe [the participants] are not comfortable [with other counseling staff]. (Pharmacist #205) |

| VASP experience—shift to conversational | ...[VASP is] more directed to [participants] than lecturing to them. Because before we used to like look at those questions and go by them and it was more us telling them what to do than them telling us their experiences... [Now] it's more like one-on-one. It's a two-way process I would say. No more [of] that lecturing pain of telling you what to do, whether they like it or not. (Nurse Counselor #15) |

| VASP experience—facilitating openness, empowerment | Before, when we used the previous approach...it was more like an approach of police approach...now, she knows that she's been caught, that she didn't use the study product. Then, you find that she will be saying anything just to please you...And, this approach...you're just letting her be in control and coming up with the strategies. And, then, too, the previous one really—we were focusing on the negatives, rather than focusing on the positives. (Nurse Counselor #12) |

| VASP experience—empowerment | [When women come up with their own goals]...it empowers them. It gives them confidence that they know they are in charge; they know what they are doing. Unlike you telling them, and then they think you think they don't know anything. (Nurse Counselor #02) |

| VASP experience—less judgmental | ...I can now interact without being judgmental...VASP has taught me that it's not as easy to take a tablet...if you give that person the chance to explain how she's managing, she can give you a hint. She can give you some advice, or she can explain herself, how she's managing to [take the tablets]. (Nurse Counselor #03) |

| VASP experience-perception of change | They are still talking in the same way like when I started the clinic. They still motivate me to use the gel if you have a problem they tell you what to do. They are still the same they have not changed.(VOICE-C Participant, gel group, August 2011) |

| VASP experience-perception of change | No, I didn't notice any changes, you know. It was just the same way, you know. They would just tell me the results of how the tablets are working and what is happening with them as well. I didn't notice any change at all. (VOICE-C Participant, tablet group, October 2011) |

| Pharmacist—product use/probing | ... [VASP has] sort of like taken away that other aspect whereby you then try...to get accurate information from the whole process...If someone then says, “I took all the time” and yet [the product count is] showing that they probably missed some doses ... [VASP] doesn't close the loop to say, okay, probably this person has a problem...we are not going to identify it because we are not marrying the two pieces of information to probably come up with a...true reflection of how the participant is actually taking the product. (Pharmacist #201) |

| Counselor—product use/probing | I think it puts them at ease not to ask about missed doses and what were the reasons of missing those doses... basically they feel that they are not being judged about failing to adhere to product use. (Counselor, open-ended final follow-up survey) |

| Pharmacist—product use/probing | Although not probing may make a participant more at ease to disclose her true adherence, it also results in lost opportunities to counsel on adherence as well as pick up other issues like gel sharing. Probing is still required for some scenarios irrespective of VASP. (Pharmacist, open-ended final follow-up survey) |

| Pharmacist—VASP lack of accountability | ...in terms of clinical trials...purely from a safety and ethical responsibility there has to be accountability...which, I think...VASP has ignored. I understand the social aspects of VASP and I understand what they're trying to do, but I really think that the way it was implemented was that they really ignored the ethical obligations of the study...You have to account for everything that you received in some way whether it's by destruction, by use or in other ways where it's lost or, you know, something like that...you have to account for it.” (Pharmacist #203) |

| Counselor—perceived participant acceptability | [The participants] are happy to know that we no longer concentrate on the study product. They are happy to know that we are also concerned about their affairs, their burdens, and also thanking them and showing them that they are very important people...So, many of our participants they're now feeling that they own this study.” (Nurse Counselor, #03) |

| Participants views: product counseling pre-VASP | Each and every time you must have a date to come back [to the clinic] and receive your tablets, you see, that is how it helps me. And the staffs are concerned - they ask you if you are still using the tablets in the right way. (VOICE-C participant, tablet group, November, 2010) |

| I think it [adherence counseling] should not be conducted at every clinic visit because the messages are the same. The [VOICE] nurses ask the same questions over and over again.(VOICE-C participant, tablet group, May 2011) | |

| Participants views: product counseling post-VASP | They [nurse counselors] encourage us that we must use them and not stop using them. [...] They tell us that without us [the participants] there is nothing they can do. We are the ones in the fore front, without us coming to the clinic they are nothing. That is why we have to make sure that we come to the clinic, they are really taking care of us. They are doing everything well for us.(VOICE-C participant, gel group, June 2011) |

| They [nurse counselors] did make a difference because they were encouraging me and it motivated me so much in such a way that I want to see the end results (VOICE-C participant, tablet group, September 2011) | |

| Counselor—perceived effectiveness of VASP | [Participants were more adherent] because of the nonjudgmental approach, when you're...showing them that you trust them and you believe in them...I think maybe [their] conscience is getting the better of them, thinking that, ‘Let's start maybe to be more adherent because these people really trust us.’ (Nurse Counselor, #12) |

| Pharmacist—perceived effectiveness of VASP | I feel that participants that had good adherence remained having good adherence, and bad ones went bad. I didn't see—I personally didn't see a major shift. (Pharmacist, #202) |

| Pharmacist—perceived effectiveness of VASP | I found that the participants, they become maybe less adherent, because then you know ... you don't ask any more what they're doing...So, they could get away with a lot of things even if they bring a lot of number of tablets that we're not expecting...[After VASP] they would forget more their study products at home because they know, ‘Okay, it's okay. They won't ask too much questions.’ (Pharmacist, #206) |

| Staff Stress | ... sometimes you also find that...maybe they're not choosing condoms consistently and you ask if they [will] bring their husband...to find a solution...The husband doesn't want to come or if the husband...is not supportive in them taking the product and doesn't want to come even for counseling...as much as she wants to be independent and to take the product freely...if the husband is giving them like that resistance, sometimes I cannot help. It's not like I can just go—drive to their house and start talking about things. You have limitations and those limitations sometimes also—they can stress you out. (Nurse Counselor, #02) |

| Staff support | The good thing is that we are three counselors and we have an opportunity to just talk about it and just have a time when we can just laugh and talk. ... You don't take things seriously especially when you discuss about it...it helps a lot. It does. (Nurse Counselor #02) |

| Futility results | I think...it was a bit of disappointment, in a sense that suddenly, these arms were getting dropped, and where something looked like it might have been promising, but suddenly, sort of it's just a bit futile. I mean honestly, a lot of time has been invested on our part, and on the participant's part. (Pharmacist #206) |

| Futility results | There was a bit of tenseness. Can I say tenseness? There was a bit of confusion to the participants. When we were exiting some participants, some participants thought those who exited were not taking their study products. There were mixed feelings about the stopping of the tenofovir. But with constant discussion with the participants, they understood that it's a research. (Nurse Counselor #03) |

| DSMB | [The remaining participants] know that everybody is looking at them, and they are supposed to make sure the VOICE study results should come out clearly... (Counselor #06) |

| DSMB | It was a lot because we...had to do the PUEVs [product end use visits]. They were long visits for the Truvada...our retention dropped because they were recalling mostly the tenofovir to be done. And we got behind with the Truvada [visits]...[staff] rescheduled the Truvada [participants] and forgot to call them back...then the participant would not take the initiative to call back and they will wait to take the phone call from the site. (Nurse Counselor #22) |

| Changing discourse about honesty | Baseline: “I think most of them now, they are quite free to discuss. But you find one or two whom you really doubt if they are using their study product. Because when you ask them, they're not open. They don't tell you much. You ask a question, they just give you a one-word answer. You probe. They just continually say “yeah. I do.” Or “maybe I was busy.” Or you ask them, “Can you remember how this dose was missed?” And they say, “I don't know.” |

| Follow up:..“they continually just repeat the same answer when you know—you know if would've probably be better to get the truth; then you also don't want to make them sense that you know they're lying. You want to still maintain their dignity and say, “Okay.” That what they're saying is true. So, that sometimes is not good for the counselor. Just continually hear lying when you know that it could have achieved the truth from this person.” (Nurse Counselor #02) | |

| Changing discourse about honesty | Baseline: “You try to probe. [...] and if she's not ready to disclose, it becomes a challenging session, because you want to find out what is happening with the product. Is she really taking it?” |

| Follow up: “Unsuccessful session is when the participant lies. You know, sometimes she forgets that she has told you this and she starts to tell you something, but you can see that she's lying, though you cannot tell her that she's lying”. (Counselor #04) |

Estimated Product Adherence Pre/Post VASP

To explore changes in product use pre- and post-VASP implementation, data subsets were created that included all VOICE participants on-product by protocol follow-up time, with the adherence measure of interest available within 6 months pre-VASP and 6 months post-VASP (measures collected after DSMB results were released were not considered for this analysis). Each participant then contributed a pair of observations to the analysis: one from the visit just before and one from after VASP implementation. All participants included in the analyses had at least one VASP counseling session between their pre- and post-assessments. Statistical tests appropriate for these paired observations were used as follows: dichotomous variables (detectable drug in plasma, self-reported use) used McNemar's test and continuous variables (e.g., CPC) were evaluated with paired t-tests.

Results

ACME with VOICE Staff

The anonymous surveys were completed by 82 staff at baseline (71 counselors and 11 pharmacists) and 75 staff at the final one-year follow-up (53 counselors and 22 pharmacists). All VOICE sites were represented in the surveys. Overall, the majority of baseline and final respondents were female (87 and 84 %) with a median age of 36 years (range 25–64) and 35 years (27–58), respectively. Eighteen baseline IDIs were completed with counselors, and 26 final IDIs were completed with 20 counselors and 6 pharmacists. Tables 2 and 3 present selected questions from the baseline and final follow-up surveys, stratified by staff role. Full survey results are available online (http://www.mtnstop shiv.org/).

Table 2.

Select baseline and final follow-up survey responses, stratified by Staff Role

| Baseline (ASP) |

Final (VASP) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All staff N (%) | Counselors N (%) | Pharmacists N (%) | All staff N (%) | Counselors N (%) | Pharmacists N (%) | |

| Total | 82 (100) | 71 (86.6) | 11 (13.4) | 75 (100) | 53 (70.7) | 22 (29.3) |

| Current approach satisfaction | ||||||

| Strongly dislike | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Dislike | 9 [11] | 7 (9.9) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (6.7) | – | 5 (22.7) |

| Like | 58 (70.7) | 49 (69) | 9 (81.8) | 41 (54.7) | 30 (56.6) | 11 (50) |

| Strongly like | 15 (18.3) | 15 (21.1) | – | 29 (38.7) | 23 (43.4) | 6 (27.3) |

| Most important rolea | ||||||

| Provide information | 9 [11] | 4 (5.6) | 5 (45.5) | 11 (14.7) | 1 (1.9) | 10 (45.5) |

| Motivate to use best | 13 (15.9) | 12 (16.9) | 1 (9.1) | 18 [24] | 15 (28.3) | 3 (13.6) |

| Motivate to use 100 % | 22 (26.8) | 21 (29.6) | 1 (9.1) | 8 (10.7) | 6 (11.3) | 2 (9.1) |

| Identify barriers/overcome | 21 (25.6) | 17 (23.9) | 4 (36.4) | 27 (36) | 21 (39.6) | 6 (27.3) |

| Reinforce need for 100 % | 14 (17.1) | 14 (19.7) | – | 3 [4] | 3 (5.7) | – |

| Other | 3 (3.7) | 3 (4.2) | – | 3 [4] | 3 (5.7) | – |

| Address adherence needs | NA | NA | NA | 5 (6.7) | 4 (7.5) | 1 (4.5) |

| Perceived participants’ openness about challenges | ||||||

| Not free | – | – | – | 2 (2.7) | – | 2 (9.1) |

| A little free | 25 (30.5) | 22 (31) | 3 (27.3) | 19 (25.3) | 10 (18.9) | 9 (40.9) |

| Free | 40 (48.8) | 34 (47.9) | 6 (54.5) | 43 (57.3) | 32 (60.4) | 11 (50) |

| Very free | 17 (20.7) | 15 (21.1) | 2 (18.2) | 11 (14.7) | 11 (20.8) | – |

| Perceived frequency of participants being honest about product use | ||||||

| A few | 12 (14.6) | 8 (11.3) | 4 (36.4) | 14 (18.7) | 6 (11.3) | 8 (36.4) |

| Some | 41 (50) | 36 (50.7) | 5 (45.5) | 38 (50.7) | 29 (54.7) | 9 (40.9) |

| Most | 29 (35.4) | 27 (38) | 2 (18.2) | 23 (30.7) | 18 (34) | 5 (22.7) |

| Current approach promotes engagement | ||||||

| Yes | 46 (56.1) | 42 (59.2) | 4 (36.4) | 46 (61.3) | 36 (67.9) | 10 (45.5) |

| No | 7 (8.5) | 5 [7] | 2 (18.2) | 5 (6.7) | 1 (1.9) | 4 (18.2) |

| Not sure | 29 (35.4) | 24 (33.8) | 5 (45.5) | 24 (32) | 16 (30.2) | 8 (36.4) |

| Current approach ‘Works’ | ||||||

| Yes | 51 (62.2) | 45 (63.4) | 6 (54.5) | 44 (58.7) | 36 (67.9) | 8 (36.4) |

| No | 7 (8.5) | 5 [7] | 2 (18.2) | 8 (10.7) | 2 (3.8) | 6 (27.3) |

| Not sure | 24 (29.3) | 21 (29.6) | 3 (27.3) | 23 (30.7) | 15 (28.3) | 8 (36.4) |

| Staff's level of stress | ||||||

| Low | 19 (23.2) | 17 (23.9) | 2 (18.2) | 27 (36) | 20 (37.7) | 7 (31.8) |

| Medium | 37 (45.1) | 32 (45.1) | 5 (45.5) | 29 (38.7) | 17 (32.1) | 12 (54.5) |

| High | 18 [22] | 15 (21.1) | 3 (27.3) | 11 (14.7) | 9 [17] | 2 (9.1) |

| Very high | 8 (9.8) | 7 (9.9) | 1 (9.1) | 8 (10.7) | 7 (13.2) | 1 (4.5) |

| Staff's experience of burnout | ||||||

| Not burned-out | 28 (34.1) | 26 (36.6) | 2 (18.2) | 43 (57.3) | 26 (49.1) | 17 (77.3) |

| A little burned-out | 43 (52.4) | 37 (52.1) | 6 (54.5) | 27 (36) | 23 (43.4) | 4 (18.2) |

| A lot burned-out | 11 (13.4) | 8 (11.3) | 3 (27.3) | 5 (6.7) | 4 (7.5) | 1 (4.5) |

Full text response choices for Most Important Role: To provide information about study product use; to motivate participant to try as best they can to use study product; to motivate participants to do whatever needs to be done to use the study product 100 % of the time; to identify barriers causing poor adherence and provide ways to overcome them; to reinforce the need for 100 % adherence; and other. The category “To address participants’ adherence related needs” was added in the final follow-up survey and not present in baseline responses

Table 3.

Opinions of VASP in final survey responses, stratified by staff role

| Total | Final follow-up survey |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| All staff N (%) 75 (100) | Counselors N (%) 53 (70.7) | Pharmacists N (%) 22 (29.3) | |

| Shift to focus on needs/experiences | |||

| Very helpful | 22 (29.3) | 17 (32.1) | 5 (22.7) |

| Helpful | 44 (58.7) | 29 (54.7) | 15 (68.2) |

| A little helpful | 8 (10.7) | 7 (13.2) | 1 (4.5) |

| Not helpful | – | – | – |

| Not applicable (NA) | 1 (1.3) | – | 1 (4.5) |

| Elimination of dosage inquiry (product count reconciliation) | |||

| Very helpful | 22 (29.3) | 18 (34) | 4 (18.2) |

| Helpful | 29 (38.7) | 25 (47.2) | 4 (18.2) |

| A little helpful | 13 (17.3) | 5 (9.4) | 8 (36.4) |

| Not helpful | 10 (13.3) | 4 (7.5) | 6 (27.3) |

| Not applicable (NA) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.9) | – |

| Willingness to recommend VASP for PrEP | |||

| Yes | 69 (92) | 53 (100) | 16 (72.7) |

| No | 6 [8] | – | 6 (27.3) |

| Staff preference | |||

| VASP approach | 49 (65.3) | 42 (79.2) | 7 (31.8) |

| Previous approach | 8 (10.7) | 1 (1.9) | 7 (31.8) |

| Both | 13 (17.3) | 7 (13.2) | 6 (27.3) |

| Neither | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.9) | – |

| NA/Don't know | 4 (5.3) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (9.1) |

| Participant preference | |||

| VASP approach | 54 (72) | 43 (81.1) | 11 (50) |

| Previous approach | 1 (1.3) | – | 1 (4.5) |

| Both | 5 (6.7) | 3 (5.7) | 2 (9.1) |

| Neither | 3 [4] | – | 3 (13.6) |

| NA/Don't know | 12 [16] | 7 (13.2) | 5 (22.7) |

| Staff support | |||

| I would like more support | 21 (28) | 16 (30.2) | 5 (22.7) |

| I like the current level of support | 48 (64) | 32 (60.4) | 16 (72.7) |

| I would like less support | 6 [8] | 5 (9.4) | 1 (4.5) |

Adherence Counseling Role and Overall ASP/VASP Experience

Overall, staff at both baseline and final follow-up indicated that they either liked or strongly liked the current adherence counseling approach, with a greater proportion strongly liking the approach at final follow-up. Although 43 % of counselors strongly liked VASP at final follow-up, only 27 % of the pharmacists had the same opinion (Table 2). Differing opinions between counselors and pharmacists about the counseling approach is a key theme that emerged throughout surveys and qualitative interviews.

At baseline, staff indicated that their most important role as an adherence counselor was “motivating participants to have 100 % product adherence” (27 %) followed by “identifying adherence barriers and providing ways to overcome them” (26 %). These responses shifted at final follow-up when the modal response (36 %) was “identifying barriers and overcoming them” followed by “motivating participants to try their best to use product” (24 %). In both surveys, pharmacists reported that “providing information” was their most important role (46 %).

VASP was designed to shift counseling away from a focus on barriers, toward a client-centered approach based on individual needs for facilitating product use in one's own specific environment/context. Despite this change in emphasis, few survey respondents at final follow-up indicated that “addressing participants’ adherence-related needs” was their most important role (7 %). However, when specifically asked about the focus on needs over barriers in VASP, the majority (88 %) felt that this shift was helpful or very helpful to the participant, regardless of staff role (Table 3).

Another key change in the VASP approach was eliminating a reconciliation step during the study visit, which occurred when adherence estimated at the pharmacy by returned study products differed from the participant's self-reported adherence. Prior to VASP, differences would lead to additional discourse between counselor and participant to reconcile self-reported adherence with product returns. When asked how helpful the removal of the reconciliation step was, most staff thought this was either very helpful (29 %) or helpful (39 %) (Table 3). Only 10 respondents (but over one quarter of pharmacists) responded that this was not helpful.

These results are consistent with the themes in the open-ended questions from the surveys and the IDIs. At baseline, the qualitative data reflected a focus on supporting participant product adherence and ensuring clear understanding of information as a measure of counseling success. At final follow-up, perspectives on successful counseling shifted toward participant engagement in the session and helping participants identify strategies to overcome stated challenges. For many counselors, the process of engaging women in developing their own strategies and goals diminished an inequitable dynamic between staff and participants. Addressing the person in her life context during adherence counseling was also a key theme that emerged in interviews. Data from matched IDIs revealed that counselors felt VASP helped shift the counseling approach away from a ‘lecture’ and toward a conversation, which was felt to improve rapport and openness. Few counselors, if any, mentioned any aspects of VASP that participants disliked. Nearly every counselor interviewed said that participants liked VASP more than the previous counseling approach, most notably because of the elimination of the reconciliation step, which could be experienced as policing or scrutinizing.

Pharmacists interviewed in the final follow-up generally felt that their role in the study was greatly diminished as a result of VASP. Prior to VASP, pharmacists felt they were able to engage with participants about their product use in ways that fostered mutual respect and a good rapport. After VASP, however, this interaction was truncated or eliminated because of a shift away from product count, leaving pharmacists with little time to interact with participants and few opportunities to offer their expertise and guidance. Pharmacists also generally felt that more product accountability should have been integrated into VASP. Separating product count from the counseling was seen as a missed opportunity for intervention and potential failure in uncovering issues like product sharing/stealing, incorrect dosing, or throwing product away. Quotes reflecting counselors and pharmacists’ views are presented in Table 4.

IDIs conducted with 38 VOICE-C participants before (N = 11) and after (N = 27) VASP implementation revealed little change in discourses related to adherence counseling. Participants did not appear to notice any modification in the counseling approach. None mentioned a change, either spontaneously or when explicitly probed about it. Nevertheless, participants were for the most part happy with the way the counseling staff interacted with them and with the counseling staff's care and professionalism. Throughout, most (but not all) said the counseling helped them and was encouraging. One difference that emerged in the post-VASP IDIs was a greater emphasis on the participants’ central role in research—participants reported being told that the study cannot be done without them and that they needed to take their product so that the study can get valid results (see Table 4).

Perceived Openness and Honesty of Participants

The majority of surveyed staff stated that, overall, participants felt free to discuss their challenges with product use (Table 2). The responses were generally consistent from baseline to final follow-up and also reflected in staff quotes (Table 4).

Most staff felt that ‘some’ participants were honest about product use, and this did not change much between baseline and follow-up (Table 2). Notably, at final follow-up, staff were sensitized to the issue of inflated self-reported adherence coming from other trial results (e.g., iPrex [Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Initiative], FemPrEP), and anticipation that poor adherence may have contributed to the early stopping of two of the products in VOICE. Many staff interviewed at final follow-up indicated that dealing with participants who were not forthcoming about adherence difficulties or were “lying” about product use was the greatest negative impact on counseling, making the sessions challenging or unsuccessful. Results from matched IDIs revealed more judgmental terms used when describing challenges with participant honesty at final follow-up. For example, one counselor at baseline said that sometimes a participant is “not ready to disclose,” and at follow-up she said, “you can see that that one is a liar.” (Table 4). This change, exhibited in a number of interviews, suggests a shift in perspective that is inconsistent with the intent of VASP but likely reflective of staff feelings in response to the perceived contribution of non-adherence to futility results.

Perceived VASP Efficacy and Acceptability

Over half of surveyed staff believed that the current adherence counseling approach (whether ASP at baseline or VASP at follow up) promoted participant engagement and “worked” (i.e., helped participants use their product consistently). However, at final follow-up, the responses of pharmacists were fairly evenly split between “yes it works” (36 %), “no it doesn't work” (27 %), and “not sure” (36 %). In contrast, the majority of counselors thought VASP worked (68 %). These results were echoed in final follow-up interviews with counselors, who expressed that participants were generally happy with VASP and felt adherence had increased after VASP implementation; although, some pharmacists interviewed expressed feeling that there was no change or a negative effect from VASP (Table 4). One pharmacist suggested that adherence counseling should be a shared experience that allows all people involved (pharmacists, nurses, counselors, doctors, etc.) to engage when necessary because often participants have different levels of comfort with different staff. As this pharmacist said, “everybody can offer a little bit of expertise...it's teamwork.”

In the final follow-up survey, staff were asked about their preferred approach; the majority preferred VASP and thought that participants preferred VASP as well. However, consistent with the trends previously described, preference for VASP was more pronounced among counselors than pharmacists. Nearly all staff recommended VASP in the context of real-word effective PrEP support (92 %)—all counselors and 73 % of pharmacists.

Staff Stress & Support

The baseline and final follow-up surveys and interviews assessed counseling staff experience with stress and burn-out as well as the resources and skills they used to cope with that stress. At both time points, most staff reported feeling a “medium” level of stress and feeling a little burned out (Table 2). Workload and overextension in their roles was a source of stress mentioned by staff in both baseline and final IDIs (Table 4). Overall, staff were satisfied with the level of support they received (64 %) (Table 3). This opinion was shared by both counselors and pharmacists. The most commonly requested improvement to staff support in the baseline and final follow-up interviews was to have more consistent opportunities to debrief both formally and informally with other staff (Table 4).

DSMB Results & Adherence Counseling Experience

The DSMB recommendations to terminate two study products because of futility created an influential context for adherence counseling and staff experience in the trial. Nearly all counselors and pharmacists felt that the process of explaining the DSMB results and exiting participants from the study was challenging and disappointing (Table 4). Many interviewees said that they themselves felt “let down” by the results and some staff “lost hope,” or felt sad and frustrated that they had devoted time and energy to something that was not working.

During IDIs, staff discussed that the DSMB decisions and subsequent exiting of a majority of participants from the study resulted in confusion and tension among participants: those participants in the process of exiting were often blamed by others for not taking their study products and being the cause of the DSMB results. When asked about how the DSMB impacted the adherence of participants remaining in the trial, many counselors said that Truvada (or placebo) participants were more motivated to continue taking their product because they wanted to see successful results. In contrast, a few interviewees said that participants just stopped coming to their clinic visits after the DSMB recommendations were released. These women did not see the point in continuing on a path that was not working. Considerable confusion also arose about which product was being stopped and when. A few staff cited media release of the futility information as a key factor in that confusion, as well as stopping participants at two different points in time.

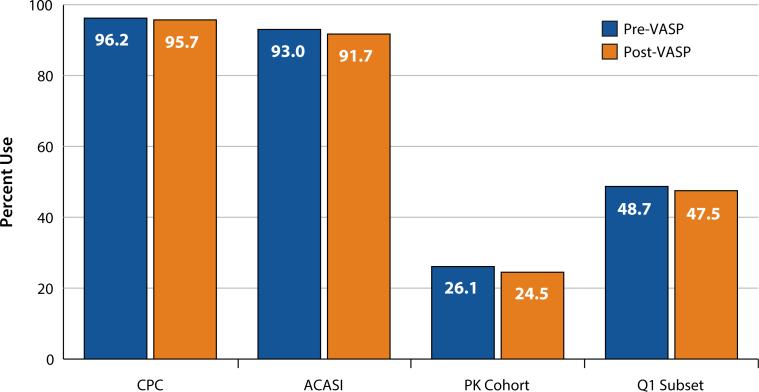

Product Use Pre- and Post-VASP (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Behavioral and biological product use by VOICE participants pre- and post-VASP CPC: Clinic Product Count included 2,958 VOICE participants in oral and vaginal groups combined, who had a monthly visit with returned CPC available within 6 months pre- and post-VASP implementation. Using a paired t test, there was no statistically significant difference pre- versus post-VASP within the oral and vaginal modes of administration, or when the groups were combined (p = 0.14). ACASI: Audio-computer assisted self-interviewing included 3,111 VOICE participants in oral and vaginal groups combined with self-reported product use information in the past week, collected at a quarterly visit within 6 months pre- and post-VASP implementation. Using McNemar's test, there was no statistically significant difference pre- versus post-VASP within the oral and vaginal modes of administration (p = 0.10). However, when combined, the decrease in reported use post-VASP was statistically significant (p = 0.02). PK cohort: Plasma TFV drug detection was measured among a subset of 379 participants on active products (oral and vaginal combined) in the VOICE random PK cohort, within 6 months pre- and post-VASP. Using McNemar's test, there was no statistically significant difference in TFV detection prevalence pre-versus post-VASP (p = 0.54). Q1 subset: Plasma TFV drug detection was assessed in a subset of participants who had plasma drug detectable at the first quarterly visit (N = 78). Using McNemar's test, there was no statistically significant difference in TFV detection prevalence pre- versus post-VASP (p = 1.00)

The CPC analysis included a subset of 2,958 (oral: 1,791; vaginal: 1,167) VOICE participants with CPC available within 6 months pre- and post-VASP. Mean adherence by CPC was high (>95 %) pre- and post-VASP with a < 1 % decrease that was not statistically significant. Similarly, the analysis of product use within the previous week by ACASI included a subset of 3,111 (oral: 1,900; vaginal: 1,211) VOICE participants with quarterly data available within 6 months pre- and post-VASP. Self-reported use by ACASI was also high pre- and post-VASP (93 vs. 92 %; p = 0.02). Detectable plasma TFV was measured among a subset of 379 participants on active products (oral and vaginal combined) in the random PK cohort, within 6 months pre- and post-VASP, with no difference overall (26 vs. 25 %; p = 0.54), or in the subset of participants (N = 78) who had plasma drug detectable at the first quarterly visit as an indicator of early product use (49 vs. 48 %; p = 1.00).

DISCUSSION

This study presents counseling staff experiences with implementing a novel client-centered adherence support program (VASP) about midway into the VOICE trial. We additionally describe the counseling experiences, product counts, self-reported, and biological measures of product use in a subset of VOICE participants pre- and post-VASP implementation. We found staff to be generally supportive of the changes in adherence counseling introduced with VASP, although attitudes varied based on staff role. Counselors appeared more positive toward VASP, which largely enhanced their role in adherence support; pharmacists perceived a diminished role with VASP and were generally less supportive. During IDIs, VOICE-C participants were generally appreciative of the professionalism and support provided by the counseling staff, however, none noticed any modification to the adherence counseling approach, style, or content. Similarly, self-reports, product- count and biological measures of product use demonstrated no differences pre- and post-VASP implementation.

Among the several limitations of this study, we want to note that plasma levels only capture recent active product use, and could reflect the “white-coat effect” of taking product just prior to study visits. Also, assessment pre- and post-VASP were conducted over a short time period, because of early closure of study arms. This study was not designed to assess the effect of VASP on adherence for a variety of reasons, including no opportunity to include an experimental design in the context of a randomized controlled trial, no fidelity evaluation, and no ability to assess “dose effect” during implementation. In other words, the participants’ behavioral and biological measures of product use cannot be interpreted directly as a measure of VASP's efficacy. Rather, the findings indicate that VASP was not able to undo the poor adherence and lack of uptake that was already fairly well established among participants at the time of its implementation. VASP started mid-trial in May 2011, and major changes in the VOICE trial because of DSMB findings of futility occurred shortly thereafter, in September and November 2011. Collection of staff experiences and participant product use overlapped with some of these changes. Although post-VASP product use data were censored to include only data collected prior to notification of assigned study arm early termination, the overall impact of discontinuation and exiting of participants cannot be estimated. Introduction of VASP to participants was framed with invitations to report on product use honestly and dispel beliefs that report of nonuse would lead to removal from the study. However, shortly after delivering these messages, participants in discontinued arms were exited from the study. This may have provided mixed messages to staff and participants. As the staff interviews revealed, the DSMB outcome was challenging and certainly modified the experience of VASP, perceptions around counseling, and the study overall. Coupled with the change in adherence counseling approach midway through the study, the two successive DSMB results were a disruptive factor that influenced participant-staff rapport and may have affected perceived participant satisfaction, product and study visit adherence, and other related issues.

One notable change introduced by VASP was the removal of a reconciliation process intended to determine why product counts differ from reported use during the counseling session.2 Counseling staff data from surveys and IDIs suggests that one of the main strengths of the VASP approach was its positive impact on the dynamic between participants and adherence counseling staff through the removal of “fault finding” that was at times described as interrogating and policing. With VASP, staff perceived that participants felt they were treated as experts in their own decision-making rather than being patronized, and this apparently created a more open, trusting, and empowering relationship dynamic. VOICE participants seem to have recognized this, through an increased sense of ownership towards the trial, noting that they felt valued by staff who emphasized their critical role in the study.

The intention with VASP was to streamline and localize adherence messaging to counselors so that participants would not receive multiple, redundant messaging throughout their study visit such that they “tuned out.” However, this delineation unintentionally shrank the pharmacist role at several sites. Initially, the VASP approach focused on counselors, overlooking pharmacists’ role in product counseling. As a result it failed to actively engage pharmacists during the development of the program, one reason why few pharmacists completed the baseline anonymous survey and no baseline IDIs included pharmacists. This oversight was corrected when VASP training took place, and is reflected by the greater representation of pharmacists during the follow-up data collection. Nevertheless, an improved approach may draw on the skills and unique perspectives of different staff involved in adherence support. Experience with VASP also highlights the importance that both staff and participants feel included in decision making, respected for their contributions, and are offered active roles in the study experience to effectively support product use-related needs. Because research sites vary considerably in clinic flow and staff-participant interactions, we recommend more flexibility in adherence approaches that support site-level decisions for staff-specific roles in adherence support. This would allow sites to adapt approaches to fit site culture and leverage available resources most effectively.

Findings from the behavioral and biological measures of product use among VOICE participants did not suggest differences pre- and post-VASP implementation. Biological assessment revealed very low overall product use that decreased over time [9]. Returned study products and reported product use remained very high and incongruent with plasma drug levels. This is in contrast to CAPRISA 004 trial, where the revised adherence support program, which shared many similarities with the VASP approach [12], and was also implemented mid-trial, resulted in increased self-reported and biologically measured product use, as well as improved effectiveness of the gel [21]. One explanation for this difference in outcome may be that in CAPRISA the improvement was mostly driven by participants with intermediate level of adherence, while those with low levels of adherence did not appear to benefit from the intervention. Notably, some adherence challenges to the BAT 24 peri-coital gel dosing used in CAPRISA are likely to be different than those for daily gel use. CAPRISA's adherence support program was denoted by a change in staff providing counseling as well as the introduction of several tools and aids during the counseling sessions [22]. In VOICE, adherence was already very low at the time VASP was implemented, no new tools or aids were introduced, the same counseling staff delivered the new intervention, and counselor-specific meetings and in-person debriefing varied in frequency. Other research has indicated that providing ongoing one-on-one supervision and support for counselors adopting a new approach may be essential for fidelity of implementation [23].

Without an experimental design to assess the effect of an adherence support intervention, we cannot control for the impact of time on product use. Thus, to assess the effect of VASP or another new counseling approach on adherence, a randomized study would be needed. Interpretation of data pre- and post-VASP is limited by the observational nature of the analysis and the proximity of early study arm closures to the implementation of VASP. That said, it may be challenging to modify adherence approaches mid-trial despite retraining staff, since staff habits and learned behaviors by experienced participants are difficult to change. The ACME project did not formally evaluate the fidelity of VASP implementation by the counseling staff.

VASP was part of a shift in prevention clinical trials, from a primarily biomedical to a more holistic perspective, embracing the importance of the socio-behavioral sciences and community engagement in clinical trials. As such, VASP contributed to a new standard for counseling approaches in microbicide research studies. VASP sought to increase openness of participant-staff discussions around product use in the context of the one-on-one counseling session. This was a first step, but we likely missed opportunities to engage others and leverage peer influence, partners, and the community as a whole in supporting product use [18]. Subsequent efforts in ongoing microbicide trials are engaging participants more systematically in group and social activities outside of the counseling session to promote sustained product use [24]. Research exploring contextual factors influencing disclosure, motivations for study participation, and investigational product use is ongoing, and may ultimately provide a more comprehensive understanding of study product adherence behavior [25, 26].

In conclusion, our data suggest that VASP was experienced by counseling staff as a useful approach that allowed for greater discussion around the many factors that influence participant adherence in their life context. Pre and post levels of product use were very similar, suggesting minimal, if any, influence of VASP on participant product use and self-reports. Modification of the counseling approach may not have been clearly denoted by staff or communicated to or noticed by participants. Modifying adherence support approaches in the midst of clinical trials is challenging, and careful consideration to include all staff should be made. Despite the limitations in drawing conclusions from these findings, guidance for future intervention efforts has emerged. We recommend that adherence support packages use an integrated multidisciplinary approach, as well as multiple modalities for participant engagement (e.g., individual, group, and community) to best fit the local culture. In addition, process monitoring to determine fidelity of implementation and potential impact on observable proxies for adherence would be well advised. Finally, research to identify factors influencing product uptake and sustained use, as well as effective strategies to promote product use at individual, social, and community levels should remain a priority on forthcoming research agendas.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the MTN-003 and MTN003C study participants, research team, site staff, and site communities. Specifically we would like to thank Dr. Jonathan Stadler, Busisiwe Magazi, Florence Mathebula and the other VOICE-C researchers at the Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute in South Africa. We would like to thank Catie Magee, Dr. Elizabeth Montgomery, Miriam Hartmann, and Andrea Hanson of WGHI/RTI International, in helping with different aspects of ACME data collection and/or study report writing. The contributions of the MTN Behavioral Research Working Group, the VOICE trial leadership, Kaila Gomez of FHI 360, and other study team members are acknowledged as critical in the development and implementation of this study. The full MTN-003 study team can be viewed at http://www.mtnstopshiv.org/people/emailgroups/86/cards. MTN-003 was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). The Microbicide Trials Network is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UM1AI068633, UM1AI068615, UM1AI106707), with co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health, all components of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Please note that the term “counseling staff” globally refers to a range of site staff (e.g., counselors, nurse/counselor and/or pharmacists) who provide product adherence counseling to participants. “Counselor” refers to the specific cadre of staff that are counselors or nurse/counselors.

Of note, behavioral adherence assessment was already separate from counseling; it was collected through ACASI and interviewer-based questionnaires.

Contributor Information

Ariane van der Straten, Women's Global Health Imperative (WGHI), RTI International, 351 California Street, Suite 500, San Francisco, CA 94104, USA; Department of Medicine, Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, University of California, San Francisco, USA.

Ashley Mayo, FHI 360, Durham, NC, USA.

Elizabeth R. Brown, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA University of Washington, Seattle, USA.

K. Rivet Amico, Center for Health, Intervention and Prevention, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA.

Helen Cheng, Women's Global Health Imperative (WGHI), RTI International, 351 California Street, Suite 500, San Francisco, CA 94104, USA.

Nicole Laborde, Women's Global Health Imperative (WGHI), RTI International, 351 California Street, Suite 500, San Francisco, CA 94104, USA.

Jeanne Marrazzo, University of Washington, Seattle, USA.

Kristine Torjesen, FHI 360, Durham, NC, USA.

References

- 1.Baeten JM, Grant R. Use of antiretrovirals for HIV prevention: what do we know and what don't we know? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10:142–51. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0157-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Straten A, Van Damme L, Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR. Unraveling the divergent results of pre-exposure prophylaxis trials for HIV prevention. AIDS (London, England) 2012;26(7):F13–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283522272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karim QA, Karim SSA, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329:1168–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. NEJM. 2012;367:399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. NEJM. 2012;367(5):423–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the bangkok tenofovir study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. NEJM. 2012;367:411–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marrazzo J, Ramjee G, Nair G, Palanee T, Mkhize B, Nakabiito C, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in women: daily oral tenofovir, oral tenofoviremtricitabine, or vaginal tenofovir gel in the VOICE Study (MTN 003). CROI.; Atlanta GA. March 3–6, 2013.2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendrix CW. Exploring concentration response in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis to optimize clinical care and trial design. Cell. 2013;155(3):515–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amico KR, Stirratt MJ. Adherence to preexposure prophylaxis: current, emerging, and anticipated bases of evidence. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(Suppl 1):s55–s60. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amico KR, Mansoor L, Corneli A, Torjesen K, van der Straten A. Adherence support approaches in biomedical HIV prevention trials: experiences, insights and future directions from four multisite prevention trials. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2143–55. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0429-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koenig LJ, Lyles C, Smith DK. Adherence to antiretroviral medications for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: lessons learned from trials and treatment studies. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(1 Suppl 2):S91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marrazzo J, Ramjee G, Nair G, Palanee T, Mkhize B, Nakabiito C, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in women: Daily oral tenofovir, oral tenofoviremtricitabine, or vaginal tenofovir gel in the voice study (mtn 003). NEJM. 2014 forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amico K, McMahan V, Goicochea P, Vargas L, Marcus JL, Grant RM, et al. Supporting study product use and accuracy in self-report in the IPREX study: next step counseling and neutral assessment. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(5):1243–59. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Microbicide trials network statement on decision to discontinue use of oral tenofovir tablets in voice, a major HIV prevention study in women. Microbicide Trials Network; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Microbicide trials network statement on decision to discontinue use of tenofovir gel in voice, a major HIV prevention study in women. 2011.

- 18.van der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, Hartmann M, Magazi B, Mathebula F, et al. Women's experiences with oral and vaginal pre-exposure prophylaxis: the voice-c qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendrix CW, Andrade A, Kashuba A, Marzinke M, Anderson PL, Moore A, et al. Tenofovir-emtricitabine directly observed dosing: 100 % adherence concentrations (hptn 066).. 21st Conference on Retorviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston. March 3–6.2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz JL, Rountree W, Kashuba ADM, Brache V, Creinin MD, Poindexter A, et al. A multi-compartment, single and multiple dose pharmacokinetic study of the vaginal candidate microbicide 1 % tenofovir gel. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansoor LE, Karim QA, Werner L, Madlala B, Ngcobo N, Cornman DH, et al. Impact of an adherence intervention on the effectiveness of tenofovir gel in the Caprisa 004 trial. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):841–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0752-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansoor LE, Abdool Karim Q, Yende-Zuma N, MacQueen KM, Baxter C, Madlala BT, et al. Adherence in the Caprisa 004 tenofovir gel microbicide trial. AIDS Behav. 2014;81:811–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0751-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dewing S, Mathews C, Schaay N, Cloete A, Louw J, Simbayi L. Behaviour change counseling for arv adherence support within primary health care facilities in the Western Cape, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1286–94. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0059-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz K, Ndase P, Torjesen K, Mayo A, Scheckter R, van der Straten A, et al. Supporting participant adherence through structured engagement activities in the MTN-020 (aspire) trial.. Community Engagement in Prevention Research, HIV Research for Prevention 2014 (HIV R4P); Cape Town, South Africa. October 28–31, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corneli A, Perry B, Agot K, Ahmed K, McKenna K, Malamatsho F, et al. Fem-prep: participant explanations for non-adherence.. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, Mass.. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Straten A, Montgomery E, Hartmann M, Levy L, Piper J, Mensch B. Strategies to explore factors impacting study product adherence among women in VOICE.. IAPAC Conference; Miami, Florida. June 8–10, 2014.2014. [Google Scholar]