Abstract

Spermatogenesis is a highly coordinated process. Signaling from nuclear hormone receptors, like those for retinoic acid, is important for normal spermatogenesis. However, the mechanisms regulating these signals are poorly understood. Mediator complex subunit 1 (MED1) is a transcriptional enhancer that directly modulates transcription from nuclear hormone receptors. MED1 is present in male germ cells throughout mammalian development, but its function during spermatogenesis is unknown. To determine its role, we generated mice lacking Med1 specifically in their germ cells beginning just before birth. Conditional Med1 knockout males are fertile, exhibiting normal testis weights and siring ordinary numbers of offspring. Retinoic acid-responsive gene products Stimulated by retinoic acid gene 8 (STRA8) and Synaptonemal complex protein 3 (SYCP3) are first detected in knockout spermatogonia at the expected time points during the first wave of spermatogenesis and persist with normal patterns of cellular distribution in adult knockout testes. Meiotic progression, however, is altered in the absence of Med1. At postnatal day 7 (P7), zygotene-stage knockout spermatocytes are already detected, unlike in control testes, with fewer pre-leptotene-stage cells and more leptotene spermatocytes observed in the knockouts. At P9, Med1 knockout spermatocytes prematurely enter pachynema. Once formed, greater numbers of knockout spermatocytes remain in pachynema relative to the other stages of meiosis throughout testis development and its maintenance in the adult. Meiotic exit is not inhibited. We conclude that MED1 regulates the temporal progression of primary spermatocytes through meiosis, with its absence resulting in abbreviated pre-leptotene, leptotene and zygotene stages, and a prolonged pachytene stage.

Introduction

Spermatogenesis is a tightly regulated process driven by a complex network of germ cell-autonomous gene transcription and extrinsic signaling from supporting somatic cells. In adult mice, seminiferous tubules contain layers of germ cells at different developmental stages. Based on the composition of germ cells in a given tubule cross-section, a seminiferous epithelial cycle comprised of 12 distinct stages can be defined (Oakberg 1956). Germ cells develop through these stages in a spatiotemporally coordinated manner, resulting in constant sperm production. Progression of a cohort of germ cells through seminiferous epithelial cycles until they are released into the epididymis is referred to as a spermatogenic wave (Perey et al. 1961).

Ligands of nuclear hormone receptors have long been known to play an important role in spermatogenesis. Mice with deficiencies in vitamin A and vitamin D have impaired fertility (Howell et al. 1963, Thompson et al. 1964, Jensen 2014). Vitamin A is metabolized to retinoic acid (RA), and thus RA signaling is a readout for vitamin A levels. RA is required for spermatogonial differentiation as well as for meiotic entry (Van Pelt & De Rooij 1990, Zhou et al. 2008, Barrios et al. 2010). Male germ cells express a number of nuclear hormone receptors in a development-specific manner. Retinoic acid receptors γ (RARG) and α (RARA) function in undifferentiated spermatogonia (Vernet et al. 2006, Gely-Pernot et al. 2012). Mice with either a global or a germ cell-specific RARG and RARA ablation have an increased number of degenerative seminiferous tubules with no mature germ cells, due to a block in spermatogonial differentiation (Gely-Pernot et al. 2012). The vitamin D receptor (VDR) is highly expressed in male germ cells (Jensen 2014). VDR null mice are infertile and have abnormal histology, although the precise mechanisms are unknown (Kinuta et al. 2000).

Mediator is a large multi-protein complex that functions as a transcriptional enhancer. Mediator complex subunit 1 (MED1) specifically interacts with nuclear hormone receptors, including RARs and VDR, to activate target genes (Zhu et al. 1997, Yuan et al. 1998, Ren et al. 2000, Urahama et al. 2005). MED1 promotes nuclear hormone receptor-mediated transcription in a ligand-dependent manner through an interaction between the LxxLL motif of MED1 and the AF-2 domain of the receptor (reviewed in (Chen & Roeder 2011)). The global knockout of Med1 in mice is embryonic lethal in mid-gestation (Ito et al. 2000, Zhu et al. 2000). Conditional knockouts have revealed numerous roles for Med1 in regulating cell differentiation and lineage specification, including myelomonocytic differentiation, erythroid development, mammary luminal epithelial cell determination, and hair differentiation (Urahama et al. 2005, Jiang et al. 2010, Stumpf et al. 2010, Oda et al. 2012).

Previous work by us demonstrated that Med1 is highly expressed throughout male germ cell development (Huszar & Payne 2013). However, the functional role of Med1 in spermatogenesis is unknown. Due to the role of MED1 in promoting nuclear hormone receptor-mediated gene transcription, we hypothesized that MED1 may play a role in regulating the onset and duration of spermatogonial differentiation. To this end, we generated mice with a conditional germ cell-specific ablation of Med1. Unexpectedly, our results establish a novel role for Med1 in regulating the dynamics of meiotic progression, modulating the amount of time spermatocytes exist in leptonema, zygonema and pachynema.

Materials and methods

Mice

All procedures and care of animals were carried out in accordance with the Stanley Manne Children’s Research Institute Animal Care and Use Committee (Manne IACUC). The Manne IACUC specifically approved this study, protocol #13-002.0. Generation of floxed Med1 mice has been described previously (Jia et al. 2004). Germ cell-specific Med1 knockout mice were generated by crossing hemizygous FVB-Tg(Ddx4-cre)1Dcas/J mice (referred to here as Vasa-cre) with floxed C57BL/6 Med1fl/fl mice to generate Vasa-cre+;Med1fl/+ F1 mice. These mice were then crossed to additional Med1fl/fl to generate Vasa-cre+;Med1Δ/fl F2 mice. Control mice used were Vasa-cre−;Med1Δ/fl or Vasa-cre+;Med1fl/+. Genotyping was performed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on genomic DNA. PCR primer sequences are available upon request. Vasa-cre mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Testis weights and body weights were measured when mice were euthanized. To assess the fertility of knockout mice, 10-week-old male mice were backcrossed to wild type female mice for a period of 5 months and the number of pups generated through such matings was evaluated.

Histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Testes were fixed at 4° C in Bouins solution, and dehydrated for paraffin embedding. Sections were cut to a thickness of 5 μM, deparaffinized and rehydrated. For histology, sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H+E). For immunohistochemistry, slides were prepared by performing antigen retrieval. Slides were boiled in 0.01 M sodium citrate, pH 6.0, for 10 min. Sections were then blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 3% goat serum in PBS. Primary antibodies were diluted in 3% goat serum in PBS and incubated with sections overnight at 4° C. Primary antibodies used for IHC were anti-SYCP3 (#ab15093, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-γH2AX (#05-636, Millipore, Billerica, MA), anti-STRA8 (#ab49602, Abcam), anti-MED1 (#ab64965, Abcam), anti-TRA98 (#ab82527, Abcam), anti-BOULE (gift of Eugene Xu, Northwestern University), anti-SOHLH1 (gift of Aleksandar Rajkovic, University of Pittsburgh). Sections were then labeled with the appropriate fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were incubated for 10 min with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Coverslips were then affixed with Vectashield anti-fade mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and samples were imaged using a Leica DMR-HC epifluorescence microscope with 10x, 20x, and 40x objectives and a QImaging Retiga 4000R camera.

Chromosome spreads

Chromosome spreads were prepared from testis following previously reported methods (Peters et al. 1997). Briefly, the tunica albuginea was removed from testes at postnatal days P7, P14, P28 and 6-weeks-old, and the seminiferous tubules were placed in a hypotonic extraction buffer containing 30 mM Tris, 50 mM sucrose, 17 mM trisodium citrate dehydrate, 5 mM EDTA, and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF) at pH 8.2 for 60 min. A 20 μL drop of 100 mM sucrose at pH 8.2 was placed on a clean glass slide. A small section of a seminiferous tubule was placed in the sucrose and minced using fine forceps. An additional 20 μL of 100 mM sucrose was added and the cells were pipetted to create a suspension. The suspension was spread across 2 new slides that had been cleaned in 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) with 0.15% Triton X-100. Cells were allowed to dry for 4 h at room temperature with high humidity. The slides were then rinsed twice in 0.4% Photoflo (Kodak, Rochester, NY). To prepare slides for imaging, slides were blocked with 5% goat serum in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. They were then incubated overnight at 4° C with anti-SYCP3 and anti-γH2AX. Finally, the slides were incubated with secondary antibodies and imaged. Cells were incubated for 10 min with DAPI and then coverslips were attached with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). Chromosome spreads were made from 3 mice of each genotype.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least three times. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were carried out using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Significance between the means was determined using Student’s t-test.

Results

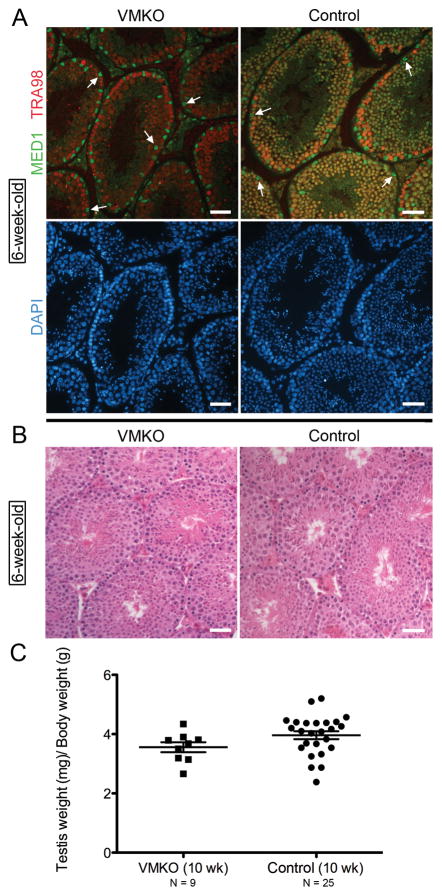

Med1 ablation in fetal prospermatogonia does not impact fertility in adult male mice

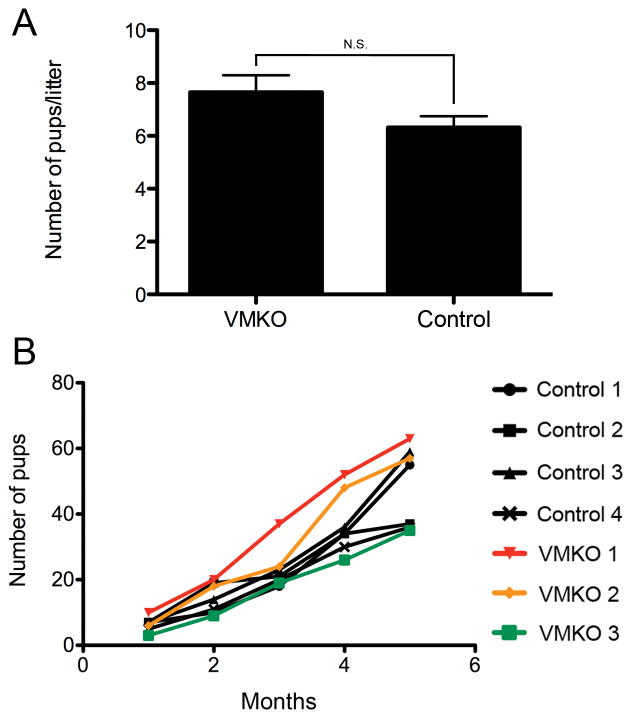

To examine the role Med1 plays in the developing male germ line, we generated germ cell-specific Med1 knockout mice by intercrossing floxed Med1 mice with Vasa-cre mice. These Vasa-cre;Med1Δ/fl mice are referred to here as Vasa-cre mediated Med1 Knock Out (VMKO) animals. Vasa-cre is specifically expressed in germ cells beginning at embryonic day 15 (Gallardo et al. 2007). To validate that Med1 was only ablated in germ cells, 6-week-old VMKO testes were examined for the co-distribution of MED1 and germ cell-specific antigen TRA98 (Tanaka et al. 1997). We did not detect any MED1 in VMKO germ cells (Fig. 1A). Only Sertoli cells and testicular interstitial cells contained MED1 in the conditional knockout samples. We then evaluated 6-week-old VMKO testes by histology and did observe any abnormalities. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed an appearance of VMKO cross-sections that was comparable to control sections (Fig. 1B). Testis weights and body weights were measured from VMKO and control animals. No differences were seen in the VMKO body weights (25.8g mean average ± 0.92g SEM vs. 24.1g mean average ± 0.74g SEM in controls) or in the testis weights (95.6mg mean average ± 4.94mg SEM vs. 95.2mg mean average ± 4.07mg SEM in controls), resulting in statistically similar testis weight:body weight ratios (Fig. 1C). We next examined the fertility of male mice lacking Med1 in their germ cells. 10-week-old VMKO males were mated with wild type females continuously for 5 months. VMKO males were fertile with normal litter sizes (Fig. 2A) and a normal accumulation of successive litters (Fig. 2B). From these data, we conclude that VMKO animals produce sperm and exhibit normal fertility.

Figure 1. Vasa-cre-mediated Med1 knockout (VMKO) testes exhibit normal morphology and weight.

A. Cross-sections of 6-week-old VMKO (left) and control (right) testes immunostained for MED1 (green) and the pan-germ cell marker TRA98 (red), and exposed to DNA stain DAPI (blue). Arrows identify Sertoli cell nuclei positive for MED1 but negative for TRA98. Scale bars = 50μm. B. Cross-sections of 6-week-old VMKO (left) and control (right) testes stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Scale bars = 50μm. C. Assessment of testis weight:body weight measurements of 10-week-old VMKO (left, N=9) and control (right, N=25) male mice. Differences are not statistically significant (Student’s t-test).

Figure 2. VMKO male mice exhibit normal fertility.

A. VMKO and control males were mated with wild type female mice for a period of 5 months. Average litter size for each group is shown. Graph exhibits mean values ± SEM. Difference is not statistically significant (N.S., Student’s t-test). B. The cumulative number of pups sired by each animal over the entire breeding period.

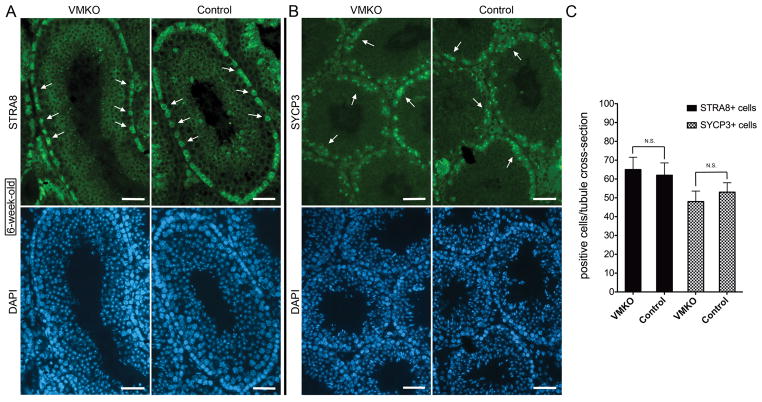

Male germ cells lacking Med1 exhibit normal STRA8 and SYCP3 localization but display altered meiotic progression

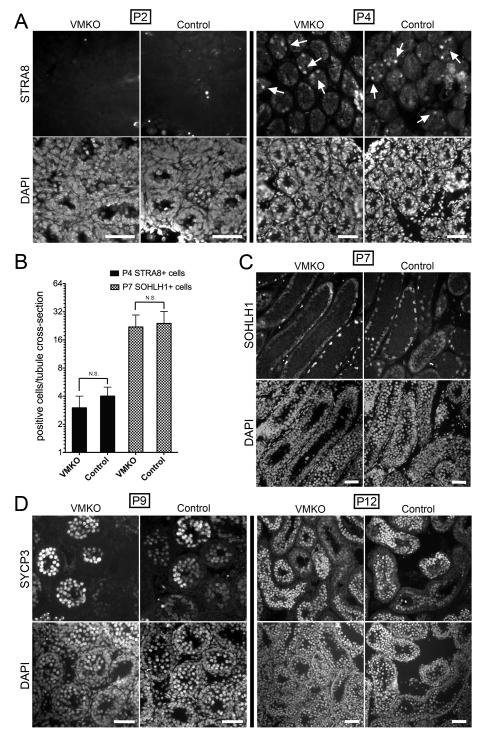

Because MED1 interacts with nuclear hormone receptors in many different cell types, we evaluated the cross-sections of adult VMKO testes for distribution patterns of retinoic acid (RA)-responsive gene products. The levels of two proteins, Stimulated by retinoic acid gene 8 (STRA8) and Synaptonemal complex protein 3 (SYCP3), increase in male germ cells upon exposure to RA (Snyder et al. 2011; Busada et al. 2014). Upregulation of Stra8 occurs through the direct engagement of response elements near the gene by activated RARs (Raverdeau et al. 2012; Kumar et al. 2013), while the increase in Sycp3 expression happens in a RAR-independent manner (Tedesco et al. 2013). Nonetheless, SYCP3 is an excellent marker of RA-induced differentiation. In 6-week-old VMKO testes, both STRA8 and SYCP3 appropriately localized to differentiating spermatogonia and meiotic spermatocytes (Figs. 3A and 3B). Equivalent numbers of STRA8+ and SYCP3+ cells were detected in VMKO seminiferous tubule cross-sections when compared to controls (Figs. 3A–C). Since adult testes reflect steady-state spermatogenesis, we next wondered whether the first-wave spermatogenic cells in developing VMKO testes exhibited comparable distribution patterns of STRA8 and SYCP3 to control testes. Endogenous RA signaling usually commences in male germ cells beginning at postnatal day 3 (P3) or P4 (Zhou et al. 2008; Snyder et al. 2010). When P2 testes were examined for STRA8, indeed both VMKO and control samples completely lacked STRA8+ cells in their seminiferous tubules (Fig. 4A). By contrast, P4 testes from VMKO and control animals exhibited STRA8+ cells in equivalent numbers (Figs. 4A–B). This finding suggests that there is no premature RA signaling response occurring in male germ cells lacking Med1.

Figure 3. Adult VMKO testes contain normal numbers of retinoic-acid responsive germ cells.

A. Cross-sections of 6-week-old VMKO (left) and control (right) testes immunostained for STRA8 (green) and exposed to DAPI (blue). Arrows identify STRA8 positive cells. Scale bars = 50μm. B. Cross-sections of 6-week-old VMKO (left) and control (right) testes immunostained for SYCP3 (green) and exposed to DAPI (blue). Arrows identify SYCP3 positive cells. Scale bars = 50μm. C. Quantitation of STRA8+ and SYCP3+ cells per seminiferous tubule cross-section in 6-week-old VMKO and control testes. Graph exhibits mean values ± SEM. Differences are not statistically significant (N.S., Student’s t-test).

Figure 4. Neonatal and juvenile VMKO testes contain normal numbers of retinoic-acid responsive germ cells.

A. Cross-sections of 2-day-old (P2, left) and P4 (right) VMKO and control testes immunostained for STRA8 (top) and exposed to DAPI (bottom). Arrows identify STRA8 positive cells. Scale bars = 50μm. B. Quantitation of STRA8+ (P4 testis) and SOHLH1+ (P7 testis) cells per seminiferous tubule cross-section in VMKO and control testes. Graph exhibits mean values ± SEM. Differences are not statistically significant (N.S., Student’s t-test). C. Cross-sections of P7 VMKO and control testes immunostained for SOHLH1 (top) and exposed to DAPI (bottom). Scale bars = 50μm. D. Cross-sections of P9 (left) and P12 (right) VMKO and control testes immunostained for SYCP3 (top) and exposed to DAPI (bottom). Scale bars = 50μm.

Spermatogonia committing to differentiation upregulate Spermatogenesis- and oogenesis-specific basic helix-loop-helix-containing protein 1 (SOHLH1) (Suzuki et al. 2012). This protein is essential for mitotic germ cell differentiation prior to entering meiosis (Ballow et al. 2006). P7 testes from VMKO males exhibited SOHLH1+ cells at numbers comparable to those in controls (Figs. 4B–C), indicating that the initial wave of spermatogonial differentiation is not disrupted in the absence of MED1. Subsequently, the first set of male germ cells enters the pre-leptotene and leptotene stages of meiosis in mice between P7 and P9, prompting our examination of VMKO testes for SYCP3 at this time window. At P9, VMKO testis cross-sections reveal an abundant number of SYCP3+ cells that is indistinguishable in scope from control sections (Fig. 4C). This pattern persists at P12, with both VMKO and control samples containing equivalent numbers of SYCP3+ cells (Fig. 4C).

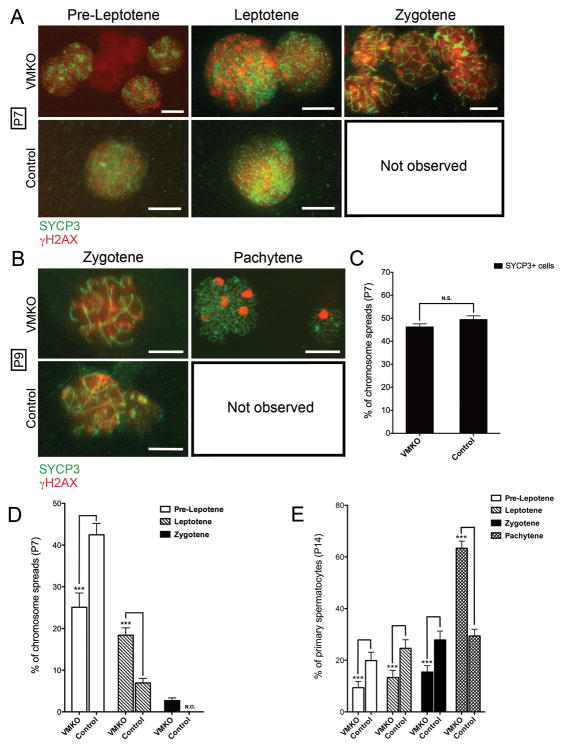

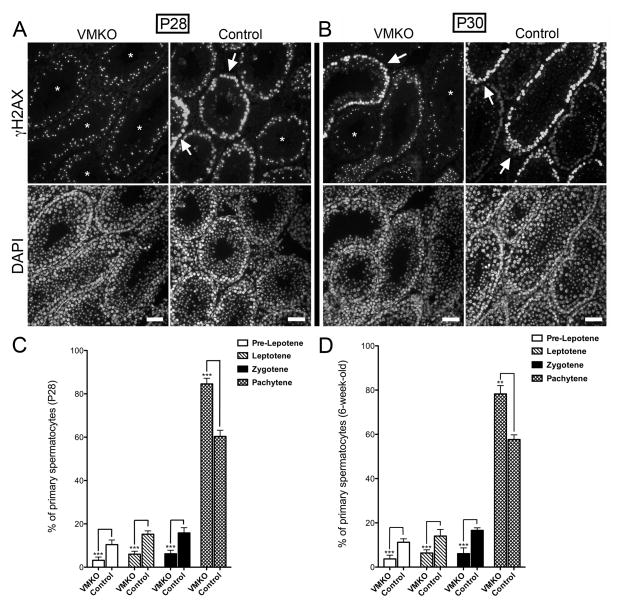

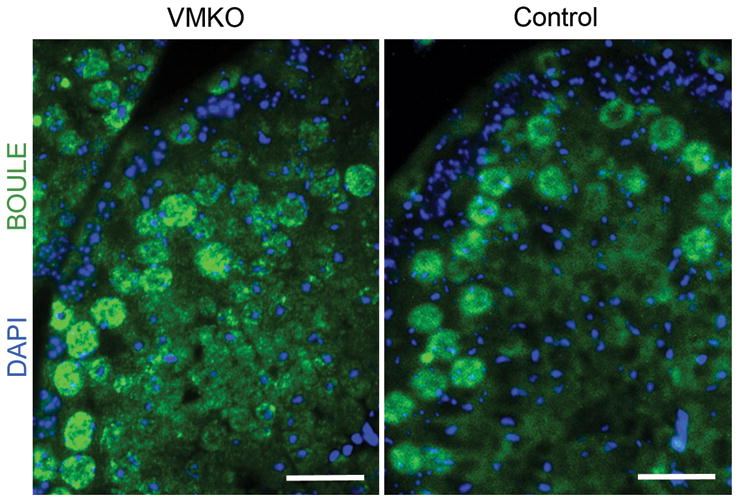

We next prepared chromosome spreads from VMKO testes, beginning at P7, to more closely evaluate the meiotic stages represented in the samples. The spreads were co-stained for SYCP3 and H2A histone family, member X (H2AFX; γH2AX), which allowed us to determine the specific stage of prophase I (Ashley 2004)). At P7, we observed zygotene-stage spermatocytes in the testes of VMKO males but not control males (Fig. 5A). At P9, we detected pachytene-stage spermatocytes in VMKO but not control testes (Fig. 5B), reflecting a premature progression through prophase I of meiosis. When the overall percentage of SYCP3+ cells in the P7 chromosome spreads was calculated, the values were statistically similar between VMKO and control samples (Fig. 5C). We determined the ratios of pre-leptotene, leptotene and zygotene spermatocytes in P7 chromosome spreads and found that VMKO samples had fewer pre-leptotene and more zygotene spermatocytes when compared to controls (Fig. 5D). P14 chromosome spreads exhibited an even greater difference in the ratios. While significantly fewer VMKO spermatocytes were in pre-leptonema, leptonema and zygonema at this time point, over twice as many VMKO cells were in pachynema when compared to control samples (Fig. 5E). γH2AX exhibits broad chromosomal distribution in leptotene and zygotene spermatocytes, but preferentially localizes to the sex chromosomes by the early pachytene stage, appearing as a concentrated focus of immunostaining in nuclei (Fernandez-Capetillo et al. 2003). To assess whether pachytene spermatocytes were overrepresented in the meiotic cell populations of VMKO testes between P14 and adulthood, we examined testis cross-sections at P28 and observed that the majority of γH2AX in VMKO samples appeared as concentrated foci (Fig. 6A). Control sections, by contrast, contained many germ cells in which γH2AX exhibited broad nuclear distribution, indicative of leptotene and zygotene spermatocytes. This pattern was also seen at P30 (Fig. 6B) and in 6-week-old testes (data not shown). Chromosome spreads from P28 testes revealed that, like in P14 testes, more VMKO spermatocytes were in pachynema when compared to control cells (Fig. 6C). This pattern persisted in 6-week-old testes, with greater numbers of pachytene spermatocytes and fewer numbers of pre-leptotene, leptotene and zygotene spermatocytes in VMKO testes when compared to controls (Fig. 6D). Finally, to determine whether post-meiotic germ cell development exhibits normal initiation in VMKO testes, we evaluated the distribution of the RNA binding protein BOULE, which is essential for round spermatids to begin the elongation process (VanGompel and Xu, 2010). Adult VMKO germ cells exhibited normal BOULE distribution (Fig. 7), suggesting that the initial stages of spermiogenesis are not disrupted by an overrepresentation of pachytene spermatocytes in the meiotic cell population.

Figure 5. VMKO male germ cells prematurely enter zygonema and pachynema in the first meiotic prophase.

A–B. Meiotic chromosome spreads were prepared from P7 (A) and P9 (B) VMKO and control testes and immunostained for SYCP3 (green) and γH2AX (red). Representative images are shown for all observed meiotic stages. Scale bars = 10 μM. C. Quantification of the percentage of P7 cells in the chromosome spreads that were SYCP3 positive. Difference is not statistically significant (N.S., Student’s t-test). D–E. Quantification of the percentage of P7 (D) and P14 (E) cells in the chromosome spreads that were pre-leptotene, leptotene, zygotene and pachytene. ***p<0.001; statistical significance calculated using Student’s t-test. N.O. = not observed. All graphs exhibit mean values ± SEM.

Figure 6. VMKO testes exhibit a higher proportion of pachytene cells relative to other meiotic stages.

A–B. Cross-sections of P28 (A) and P30 (B) VMKO and control testes immunostained for γH2AX (top) and exposed to DAPI (bottom). Asterisks demarcate seminiferous tubules enriched with pachytene cells (concentrated foci of γH2AX). Arrows identify leptotene and zygotene spermatocytes. Scale bars = 50μm. C–D. Quantification of the percentage of P28 (C) and 6-week-old (D) cells in the chromosome spreads that were pre-leptotene, leptotene, zygotene and pachytene. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; statistical significance calculated using Student’s t-test. Graphs exhibit mean values ± SEM.

Figure 7. VMKO testes exhibit normal post-meiotic germ cell development.

Cross-sections of 6-week-old VMKO (left) and control (right) testes immunostained for BOULE (green) and exposed to DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 25μm.

Discussion

In this study, we have described a role for MED1 in regulating the temporal progression of primary spermatocytes through meiosis. Med1-depleted germ cells prematurely appear in zygonema and pachynema during the initial wave of spermatogenesis, with a reduced proportion of cells remaining in pre-leptonema and leptonema. Once formed, pachytene cells lacking Med1 progress with temporal dynamics that result in a meiotic exit comparable to control cells. Subsequent spermatogenic waves retain this pattern of prolonged pachynema relative to other stages of the first meiotic prophase. Ultimately, fertility is normal in Med1 conditional knockout males, resulting in normal numbers of offspring.

The role MED1 plays in enhancing transcription in vivo from nuclear hormone receptors, including VDR, estrogen receptors, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, is well described (Oda et al. 2003, Jia et al. 2004, Zhang et al. 2005). While MED1 physically interacts with RARs, a functional role for a MED1-RAR interaction in vivo has not been shown. One study found that a human promyelocytic leukemia cell line was resistant to RA-induced differentiation in vitro following transient Med1 knockdown (Urahama et al. 2005). RA is the main driver of meiotic entry in germ cells (Griswold et al. 2012). While loss of Med1 does not inhibit spermatogonial differentiation or entry into meiosis, the Med1 loss-of-function effects alters the timing of meiotic progression once cells have committed to this process. It is important to note that MED1 interacts with members from other classes of transcription factors, including the GATA family (Crawford et al. 2002). Thus, it is possible that MED1 regulates transcription in developing germ cells through a non-hormone receptor or another previously unidentified binding partner.

Several other factors have been shown to play a role in the temporal progression of meiosis. Insulin-like factor 6 is essential for late pachynema of prophase I, with few germ cells differentiating beyond this stage in its absence (Burnicka-Turek et al. 2009). Loss of Dicer 1 in the male germline results in a higher proportion of leptotene and zygotene cells and a reduced proportion of pachytene, diplotene and metaphase I cells (Romero et al. 2011; Greenlee et al. 2012). Claudin 3 knockdown in the testis, meanwhile, generates meiotic cells that exhibit a prolonged preleptonema with respect to other stages in meiosis (Chihara et al. 2013). In light of these previous findings, MED1 could mediate its activity in spermatocytes downstream of growth factor secretion, tight junction formation or non-coding RNA production. The mechanism of how MED1 regulates meiotic progression remains to be defined in further detail.

The spermatogenic process relies on a high level of coordination between many different cell types. While RA and other extrinsic signaling molecules play key roles influencing spermatogonial differentiation and meiosis, the effects of these molecules are ultimately regulated within the germ cells themselves. Here, we describe a role for MED1 in regulating meiotic progression in male germ cells. Together with other transcriptional and epigenetic regulators, MED1 appears to modulate the influence of extrinsic signaling factors on germ cells to correctly time key events during spermatogenesis.

Acknowledgments

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge the Children’s Research Fund of the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and the Stanley Manne Children’s Research Institute for its generous financial support to J.M.H. (Outstanding Graduate Student Award) and C.J.P. (Institutional Funds). C.J.P. is the recipient of an NIH Pathway-to-Independence Award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R00 HD055330)

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- Ashley T. The mouse “tool box” for meiotic studies. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004;105:166–171. doi: 10.1159/000078186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballow D, Meistrich ML, Matzuk M, Rajkovic A. Sohlh1 is essential for spermatogonial differentiation. Dev Biol. 2006;294:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios F, Filipponi D, Pellegrini M, Paronetto MP, Di Siena S, Geremia R, Rossi P, De Felici M, Jannini EA, Dolci S. Opposing effects of retinoic acid and FGF9 on Nanos2 expression and meiotic entry of mouse germ cells. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:871–880. doi: 10.1242/jcs.057968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnicka-Turek O, Shirneshan K, Paprotta I, Grzmil P, Meinhardt A, Engel W, Adham IM. Inactivation of insulin-like factor 6 disrupts the progression of spermatogenesis at late meiotic prophase. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4348–4357. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busada JT, Kaye EP, Renegar RH, Geyer CB. Retinoic acid induces multiple hallmarks of the prospermatogonia-to-spermatogonia transition in the neonatal mouse. Biol Reprod. 2014;90:64. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.114645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Roeder RG. Mediator-dependent nuclear receptor function. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:749–758. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chihara M, Ikebuchi R, Otsuka S, Ichii O, Hashimoto Y, Suzuki A, Saga Y, Kon Y. Mice stage-specific claudin 3 expression regulates progression of meiosis in early stage spermatocytes. Biol Reprod. 2013;89:3. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.107847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford SE, Qi C, Misra P, Stellmach V, Rao MS, Engel JD, Zhu Y, Reddy JK. Defects of the heart, eye, and megakaryocytes in peroxisome proliferator activator receptor-binding protein (PBP) null embryos implicate GATA family of transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3585–3592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107995200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Capetillo O, Mahadevaiah SK, Celeste A, Romanienko PJ, Camerini-Otero RD, Bonner WM, Manova K, Burgoyne P, Nussenzweig A. H2AX is required for chromatin remodeling and inactivation of sex chromosomes in male mouse meiosis. Dev Cell. 2003;4:497–508. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo T, Shirley L, John GB, Castrillon DH. Generation of a germ cell-specific mouse transgenic Cre line, Vasa-Cre. Genesis. 2007;45:413–417. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gely-Pernot A, Raverdeau M, Celebi C, Dennefeld C, Feret B, Klopfenstein M, Yoshida S, Ghyselinck NB, Mark M. Spermatogonia differentiation requires retinoic acid receptor gamma. Endocrinology. 2012;153:438–449. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee AR, Shiao MS, Snyder E, Buaas FW, Gu T, Stearns TM, Sharma M, Murchison EP, Puente GC, Braun RE. Deregulated sex chromosome gene expression with male germ cell-specific loss of Dicer1. Plos One. 2012;7:e46359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griswold MD, Hogarth CA, Bowles J, Koopman P. Initiating meiosis: the case for retinoic acid. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:35. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.096610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell JM, Thompson JN, Pitt GA. Histology of the lesions produced in the reproductive tract of animals fed a diet deficient in vitamin A alcohol but containing vitamin A acid. I. The male rat. J Reprod Fertil. 1963;5:159–167. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0050159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huszar JM, Payne CJ. MicroRNA 146 (Mir146) Modulates Spermatogonial Differentiation by Retinoic Acid in Mice. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:15. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.103747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Yuan CX, Okano HJ, Darnell RB, Roeder RG. Involvement of the TRAP220 component of the TRAP/SMCC coactivator complex in embryonic development and thyroid hormone action. Mol Cell. 2000;5:683–693. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MB. Vitamin D and male reproduction. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:175–186. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Qi C, Kashireddi P, Surapureddi S, Zhu YJ, Rao MS, Le Roith D, Chambon P, Gonzalez FJ, Reddy JK. Transcription coactivator PBP, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-binding protein, is required for PPARalpha-regulated gene expression in liver. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24427–24434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Hu Q, Ito M, Meyer S, Waltz S, Khan S, Roeder RG, Zhang X. Key roles for MED1 LxxLL motifs in pubertal mammary gland development and luminal-cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6765–6770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001814107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinuta K, Tanaka H, Moriwake T, Aya K, Kato S, Seino Y. Vitamin D is an important factor in estrogen biosynthesis of both female and male gonads. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1317–1324. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.4.7403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Cunningham TJ, Duester G. Resolving molecular events in the regulation of meiosis in male and female germ cells. Sci Signal. 2013;6:e25. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakberg EF. A description of spermiogenesis in the mouse and its use in analysis of the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium and germ cell renewal. American Journal of Anatomy. 1956;99:391–413. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000990303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y, Hu L, Bul V, Elalieh H, Reddy JK, Bikle DD. Coactivator MED1 ablation in keratinocytes results in hair-cycling defects and epidermal alterations. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1075–1083. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y, Sihlbom C, Chalkley RJ, Huang L, Rachez C, Chang CP, Burlingame AL, Freedman LP, Bikle DD. Two distinct coactivators, DRIP/mediator and SRC/p160, are differentially involved in vitamin D receptor transactivation during keratinocyte differentiation. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:2329–2339. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perey B, Clermont Y, Leblond CP. The wave of the seminiferous epithelium in the rat. American Journal of Anatomy. 1961;108:47–77. [Google Scholar]

- Peters AH, Plug AW, van Vugt MJ, de Boer P. A drying-down technique for the spreading of mammalian meiocytes from the male and female germline. Chromosome Res. 1997;5:66–68. doi: 10.1023/a:1018445520117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raverdeau M, Gely-Pernot A, Feret B, Dennefeld C, Benoit G, Davidson I, Chambon P, Mark M, Ghyselinck NB. Retinoic acid induces Sertoli cell paracrine signals for spermatogonia differentiation but cell autonomously drives spermatocyte meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16582–16587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214936109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, Behre E, Ren Z, Zhang J, Wang Q, Fondell JD. Specific structural motifs determine TRAP220 interactions with nuclear hormone receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5433–5446. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5433-5446.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero Y, Meikar O, Papaioannou MD, Conne B, Grey C, Weier M, Pralong F, De Massy B, Kaessmann H, Vassalli JD, Kotaja N, Nef S. Dicer1 depletion in male germ cells leads to infertility due to cumulative meiotic and spermiogenic defects. Plos One. 2011;6:e25241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EM, Small C, Griswold MD. Retinoic acid availability drives the asynchronous initiation of spermatogonial differentiation in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2010;83:783–790. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.085811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EM, Davis JC, Zhou Q, Evanoff R, Griswold MD. Exposure to retinoic acid in the neonatal but not adult mouse results in synchronous spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:886–893. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.089755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumpf M, Yue X, Schmitz S, Luche H, Reddy JK, Borggrefe T. Specific erythroid-lineage defect in mice conditionally deficient for Mediator subunit Med1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21541–21546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005794107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Ahn HW, Chu T, Bowden W, Gassei K, Orwig K, Rajkovic A. SOHLH1 and SOHLH2 coordinate spermatogonial differentiation. Dev Biol. 2012;361:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Pereira LA, Nozaki M, Tsuchida J, Sawada K, Mori H, Nishimune Y. A germ cell-specific nuclear antigen recognized by a monoclonal antibody raised against mouse testicular germ cells. Int J Androl. 1997;20:361–366. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.1998.00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco M, Desimio MG, Klinger FG, De Felici M, Farini D. Minimal concentrations of retinoic acid induce stimulation by retinoic acid 8 and promote entry into meiosis in isolated pregonadal and gonadal mouse primordial germ cells. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:145. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.106526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JN, Howell JM, Pitt GA. Vitamin A and reproduction in rats. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1964;159:510–535. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1964.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urahama N, Ito M, Sada A, Yakushijin K, Yamamoto K, Okamura A, Minagawa K, Hato A, Chihara K, Roeder RG, Matsui T. The role of transcriptional coactivator TRAP220 in myelomonocytic differentiation. Genes Cells. 2005;10:1127–1137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Pelt AM, De Rooij DG. The origin of the synchronization of the seminiferous epithelium in vitamin A-deficient rats after vitamin A replacement. Biol Reprod. 1990;42:677–682. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod42.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanGompel MJ, Xu EY. A novel requirement in mammalian spermatid differentiation for the DAZ-family protein Boule. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2360–2369. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernet N, Dennefeld C, Rochette-Egly C, Oulad-Abdelghani M, Chambon P, Ghyselinck NB, Mark M. Retinoic acid metabolism and signaling pathways in the adult and developing mouse testis. Endocrinology. 2006;147:96–110. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan CX, Ito M, Fondell JD, Fu ZY, Roeder RG. The TRAP220 component of a thyroid hormone receptor- associated protein (TRAP) coactivator complex interacts directly with nuclear receptors in a ligand-dependent fashion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7939–7944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Krutchinsky A, Fukuda A, Chen W, Yamamura S, Chait BT, Roeder RG. MED1/TRAP220 exists predominantly in a TRAP/ Mediator subpopulation enriched in RNA polymerase II and is required for ER-mediated transcription. Mol Cell. 2005;19:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Nie R, Li Y, Friel P, Mitchell D, Hess RA, Small C, Griswold MD. Expression of stimulated by retinoic acid gene 8 (Stra8) in spermatogenic cells induced by retinoic acid: an in vivo study in vitamin A-sufficient postnatal murine testes. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:35–42. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Qi C, Jain S, Rao MS, Reddy JK. Isolation and characterization of PBP, a protein that interacts with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25500–25506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Qi C, Jia Y, Nye JS, Rao MS, Reddy JK. Deletion of PBP/PPARBP, the gene for nuclear receptor coactivator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-binding protein, results in embryonic lethality. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14779–14782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]