Abstract

An elevated level of homocysteine called hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy) is associated with pathological cardiac remodeling. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) acts as a cardioprotective gas, however the mechanism by which H2S mitigates homocysteine mediated pathological remodeling in cardiomyocytes is unclear. We hypothesized that H2S ameliorates HHcy mediated hypertrophy by inducing cardioprotective miR-133a in cardiomyocytes. To test the hypothesis, HL1 cardiomyocytes were treated with: 1) plain medium (control, CT), 2) 100μM of homocysteine (Hcy), 3) Hcy with 30μM of H2S (Hcy+H2S), and 4) H2S for 24 hour. The levels of hypertrophy markers: c-fos, atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), and beta-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC), miR-133a and its transcriptional inducer myosin enhancer factor- 2c (MEF2C) were determined by Western blotting, RT-qPCR, and immunofluorescence. The activity of MEF2C was assessed by co-immunoprecipitation of MEF2C with histone deacetylase -1(HDAC1). Our results show that H2S ameliorates homocysteine mediated up regulation of c-fos, ANP and β-MHC, and down regulation of MEF2C and miR-133a. HHcy induces the binding of MEF2C with HDAC1, whereas H2S releases MEF2C from MEF2C-HDAC1 complex causing activation of MEF2C. These findings elicit that HHcy induces cardiac hypertrophy by promoting MEF2C-HDAC1 complex formation that inactivates MEF2C causing suppression of anti-hypertrophy miR-133a in cardiomyocytes. H2S mitigates hypertrophy by inducing miR-133a through activation of MEF2C in HHcy cardiomyocytes. To our knowledge this is a novel mechanism of H2S mediated activation of MEF2C and induction of miR-133a and inhibition of hypertrophy in HHcy cardiomyocytes.

Keywords: Hyperhomocysteinemia, Hydrogen sulfide, MiR-133a, Hypertrophy, MEF2C, HDAC

1. Introduction

Homocysteine (Hcy) is a sulfur containing non-protein coding amino acid that contributes to cardiovascular diseases [1, 2]. Elevated level of Hcy is called hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy), which is associated with increased incidence of mortality [3]. It is considered that 5μM/L raise in plasma Hcy level increases the risk of coronary artery disease by as much as 0.5mmol/L of cholesterol [4]. HHcy differentially regulates miRNAs [5] and attenuates beta-adrenergic signaling by suppressing stimulatory G protein (Gs) [6], which lead to pathological cardiac remodeling. HHcy is caused either due to impaired re-methylation process, which involves methyl tetrahydrofolate reductase enzyme and folic acid and B vitamins co-factors, or defect in any of the three Hcy metabolic enzymes: cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfur transferase (3MST). These three enzymes convert Hcy into hydrogen sulfide (H2S) [7]. Contrary to HHcy, H2S is a cardioprotective gas [8–11]. H2S ameliorates cardiac dysfunction at several levels. It preserves mitochondrial function in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury [12], suppresses activation of nuclear factor kappa B and mitogen activated protein kinases in Coxsackie virus B3 infected rat cardiomyocytes [13], mitigates endoplasmic reticulum stress in high fat diet fed mice [14], induces Nrf2 transcription factor to alleviate oxidative stress in myocardial ischemia [15], and up regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase for nitric oxide bioavailability in ischemia-reperfusion injury [16]. Although the pathological effect of HHcy and the cardioprotective role of H2S are well documented, the mechanism by which HHcy induces pathological cardiac remodeling and H2S mitigates that remodeling is poorly understood.

MicroRNAs (miRs) are a newly emerged tiny, con-coding, regulatory RNAs that modulate gene expression either by mRNA degradation or translational repression [17]. They are recognized as a novel therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases [18, 19]. In human hearts, >800 miRNAs are present and >250 miRNAs are differentially regulated in pathological hearts [20]. MiR-133a is one of the most abundant miRNA in the heart [21]. It is cardioprotective and mitigates cardiac fibrosis [22, 23] and hypertrophy [24]. MiR-133a transcription is regulated by myosin enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C) [25]. Members of the MEF2 family are repressed when they make complex with histone deacetylase (HDAC) [26]. Therefore, formation of MEF2C-HDAC complex inactivates MEF2C. However, role of Hcy in formation of MEF2C-HDAC complex, and thereby transcription of miR-133a in cardiomyocytes is unclear. Also, whether the H2S ameliorates the effect of Hcy on MEF2C-HDAC complex formation, and miR-133a deregulation is nebulous. Accordingly, we investigated the role of Hcy on MEF2C mediated attenuation of miR-133a, and H2S in restoring the level of miR-133a in HHcy cardiomyocytes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell culture and treatments

HL1 cardiomyocytes were cultured in Claycomb media as described elsewhere [5]. In brief, cells are treated with only incomplete (serum deprived) medium (control, CT), Hcy (100μm) and/or H2S (30μm) in the incomplete medium for 24 hour. We selected 100 μm dose of Hcy because at in vitro level, lower dose of Hcy (30 μm) did not engender significant effect on pathological remodeling in cardiomyocytes [5]. It is also reported that inborn errors of Hcy metabolism results into elevation of plasma Hcy level from 200–300 μm/L, which is markedly higher than the mild elevation (>15 μm/L) of Hcy in humans [27]. Therefore, 100 μm is physiologically relevant dose of Hcy. After 24 hour, cells were used for either protein extraction or imaging. Hematoxylin-Eosin (H-E) (#HAE-1, ScyTeK laboratories Inc., USA) staining of cells were performed after fixing the cells with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were observed under bright field color microscope. For inhibiting miR-133a, we used anti-miR-133a oligonucleotide (AMO-133a) (Catalogue # AM17000, ID: AM10413 Ambion, Life technologies Inc., USA). AMO-133a was transfected before treatment with Hcy and H2S. In brief, 75 picomole AMO-133a was transfected with lipofectamine (6μl per well of 6 well plate) in final volume of 300μl optiMEM (Catalogue #31985-70, Gibco Life technologies Inc., USA) for 8 hours. Cells were then treated for Hcy + H2S for 24 hour in antibiotic free medium.

2.2. Western Blotting

Radio-Immuno-Precipitation Assay (RIPA, catalogue # BP-115D, Boston BioProducts, USA) lysis buffer was used to isolate total protein from HL1 cells after treatment. The quantity of protein was estimated by using Pierce BCA protein Assay kit (catalogue # 23227, Thermo scientific, USA). Western blotting was performed using SDS-PAGE (10%). Protein was transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (catalogue #162-0115, Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA) by overnight transfer at 4°C. The primary antibodies of MEF2C (catalogue # ab79436, Abcam, USA), β-MHC (catalogue # ab172967, Abcam, USA), ANP (catalogue # AB5490, Millipore, USA) and β-actin (catalogue # sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotech, USA) were diluted in the ratio of 1:1000. The secondary antibodies, anti-mouse IgG-HRP (catalogue # sc-2005, Santa Cruz Biotech, USA) and anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (catalogue # sc -2054, Santa Cruz Biotech, USA) were diluted in the ratio of 1:2000. The membranes were developed and band intensity was analyzed by ChemiDoc software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA).

2.3. miRNA assay

For miRNA assay, RNA was isolated from HL1 cells using miRVana™ miRNA Isolation Kit (catalogue # AM1560 Life technologies, USA). The RNAs quality was assessed by NanoDrop 2000c (Thermo Scientific Inc., USA) and RNAs with 260/280 >1.8 and 260/230 >1.8 were used for miR-133a assay using Taqman probes. The miRNA Reverse Transcriptase-PCR followed by Taqman qPCR were performed using miR-133a (Assay ID-002246) and U6 SnRNA (Assay ID: 001973) specific primers following the manufacturer’s instruction and protocol (Life technologies, USA). The details of the protocol is published elsewhere [28]. U6 SnRNA was used as an endogenous control for miR-133a. The miRNA PCR reactions mixtures were amplified in a 96 well plate in Bio-Rad CFX qPCR Instrument, and data were analyzed by integrated BioRad CFX Manager3.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA).

2.4. Immunocytochemistry

In vitro immunocytochemistry studies on HL1 cells were performed using standard protocol. In brief, cells were cultured in 24 well plates and treated for 24 hour in incomplete medium. After treatment medium was removed and cells were washed with1xPBS, pH 7.4 followed by fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde (catalogue #158127, Sigma, USA) for 40 minutes. Fixed cells were washed in 1xPBS for 5 minutes three times, then permeabilized in 0.01% Triton-X-100 in 1xPBS for 30 minutes, and blocked in 1% BSA in PBS for 1 hour. After blocking solution was removed, cells were washed with 1xPBS for 5 minutes three times followed by incubation in diluted primary antibody solution in 1xPBS with 0.1% BSA overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies used were: 5μg/mL of rabbit anti-Atrial Natriuretic Peptide (catalogue # AB5490, Millipore, USA), 1:400 dilution of c-fos (9F6) Rabbit mAb (catalogue # 2250, Cell Signaling Technologies, USA), 1:500 dilution of rabbit anti-MEF2C (catalogue# ab79436, Abcam, USA), and 1:500 dilution of rabbit anti-β-MHC (catalogue # ab172967, Abcam, USA). Primary antibody was removed after 24 hour at 4°C, and cells were washed in 1xPBS for 5 minutes three times at room temperature. Cells were incubated with secondary antibody for 1 hour in dark. The secondary antibodies were: chicken anti-rabbit-IgG and/or anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488/594 conjugated secondary antibodies (catalogue # A21441, A21200, A21201, Life Technologies, USA). Then cells were washed with 1x PBS for 5 minutes 3 times, and incubated with 1μg/ml DAPI solution in 1xPBS (catalogue # A1001, AppliChem, USA) for 1 minute. Cells were washed twice in 1xPBS for 5minute each and observed under EVOS Cell Imaging Systems (Life Technologies, USA). The intensity of color was analyzed by Image J software (NIH, USA).

2.5. Co-Immunoprecipitation

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) was performed using dynabeads (catalogue # 10003D, Life Technologies, USA) following the protocol from the company. In brief, cells were lysed using IP lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific, USA). Diluted anti-HDAC1 antibody (catalogue # ab46985, Abcam, USA) was added to dynabeads and mixed by gentle shaking and incubated for 10 minute at room temperatures. Tubes were placed on a magnet and supernatant was removed. Beads were re-suspended in PBS and washed three times with PBS-Tween-20. Protein samples were added in the tubes and gently pipetted to re-suspend the samples. Tubes were incubated with rotation (15 rpm) for 30 minute at room temperature. After incubation beads were washed and transferred into a new tube. Elution was done with sample buffer having β-mercaptoethanol. 10% SDS-PAGE was performed and membranes were blotted with MEF2C and HDAC1 antibodies. In another gel, same protein lysates were electrophoresed for β-actin to confirm the equal loading of proteins that was used for immunoprecipitation.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The values are represented as mean ± standard error of mean (S.E). To determine the statistical significance between the groups, one way analyses of variance (ANOVA) was performed, which was followed by Newman–Keuls method to determine differences in means between the groups. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. H2S mitigates HHcy induced hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes

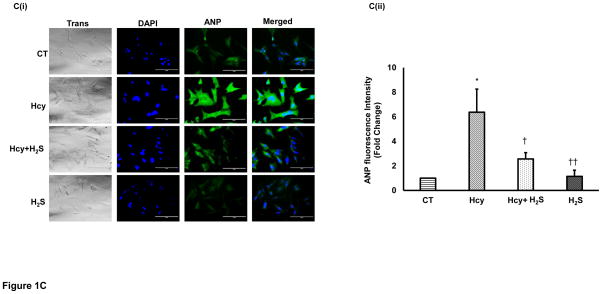

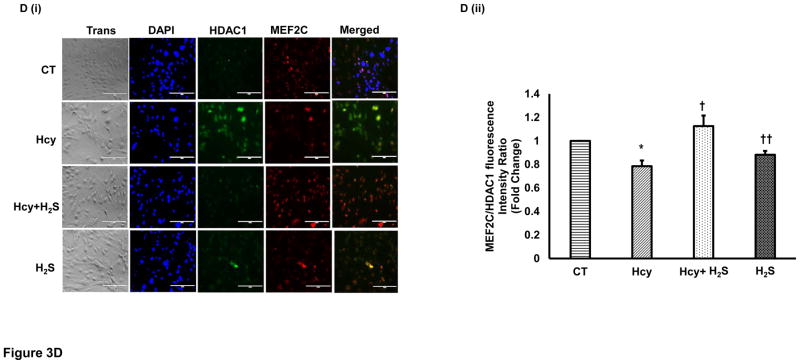

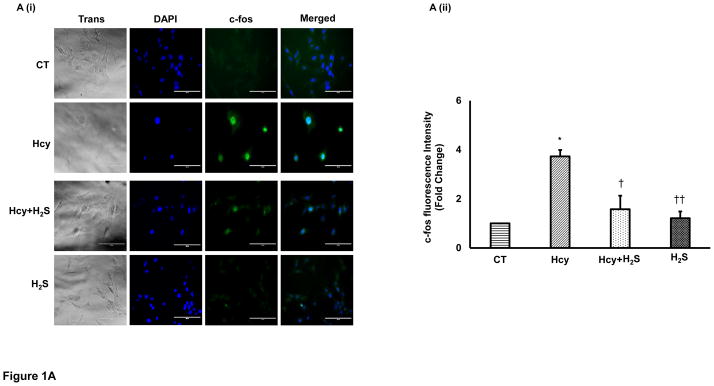

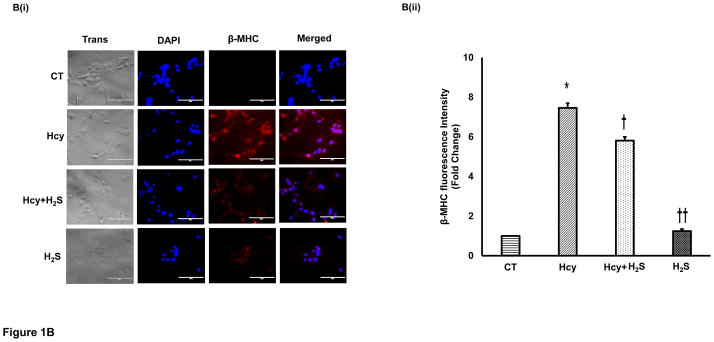

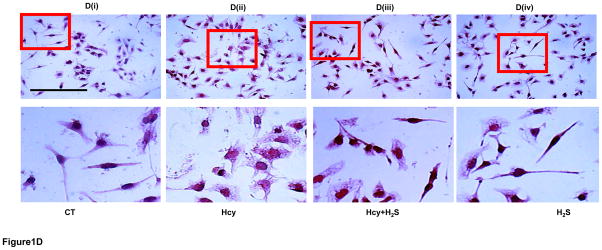

To determine the hypertrophic effect of Hcy on cardiomyocytes, we treated HL1 cells with high dose (100μM) of Hcy for 24 hour as per the published report [29], and determined the expression of β-MHC, ANP and c-fos. We found that HHcy induces both the early hypertrophy maker c-fos (Figure 1A), and late hypertrophy markers β-MHC (Figure 1B), and ANP (Figure 1C) in the cardiomyocytes. To assess the cardioprotective effect of H2S in HHcy mediated hypertrophy, the cardiomyocytes were treated with both Hcy and H2S (30μM). Interestingly, the levels of both early and late hypertrophy markers were significantly down regulated in Hcy and H2S (Hcy+ H2S) treated group as compared to the Hcy group (Figure 1A–C) suggesting that H2S mitigates the initiation and progression of HHcy mediated hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes. Furthermore, there was no significant difference between CT and H2S groups (Figure 1A–C) suggesting that H2S maintains the normal size of the cardiomyocytes. The one-way ANOVA showed significant difference among the mean value of c-fos, ANP and BNP among the groups. These molecular studies clearly show that H2S retains the size of healthy cardiomyocytes but has an anti-hypertrophic effect in HHcy cardiomyocytes. To reinforce our results, we observed the changes in cell morphology in the four groups (CT, Hcy, Hcy+ H2S, and H2S) by H-E staining. Our results show that cells were enlarged and morphology of the cells were more round –shape in Hcy as compared to the CT, where the shape of the cells were triangular with tapering ends. Notably, in Hcy+ H2S, the cell size and morphology were more like CT (Figure 1D). These result are consistent with the molecular data that H2S alleviates Hcy mediated hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes (Figure 1A–C). In cells, which were treated with H2S only, the cell size and morphology were similar to that of the CT cells suggesting that the treated dose of H2S did not have any significant effect on the size and morphology of the cardiomyocytes.

Figure 1.

H2S mitigates Hcy mediated induction of hypertrophy in the cardiomyocytes. Immunofluorescence (IF) of c-fos, β-MHC, and ANP in the four groups of HL1 cardiomyocytes: control (CT), homocysteine treated (Hcy), Hcy and H2S treated (Hcy+ H2S), and H2S treated (H2S). A. (i) Representative IF of c-fos (green) in the four groups. Dapi (blue) represents nucleus. A (ii) Bar graph shows quantitative analyses of green color and represented as mean ± S. E. B (i). Representative IF of β-MHC (red) in the four groups. B (ii) Bar graph shows quantitative analyses of red color and values are mean ± S. E. C (i). Representative IF of ANP (green) in the four groups C (ii). Bar graph shows quantitative analyses of green color and values are represented as mean ± S. E. Scale bar: 100μm. D (i) – (iv). Hematoxylin and Eosin staining of HL1 cardiomyocytes in the four groups. The changes in the size and morphology of cardiomyocytes are shown in high magnification. Scale bar: 100μm. N=3. *, p<0.05 compared to CT; †, p<0.05 compared Hcy; ††, p<0.05 compared Hcy+H2S.

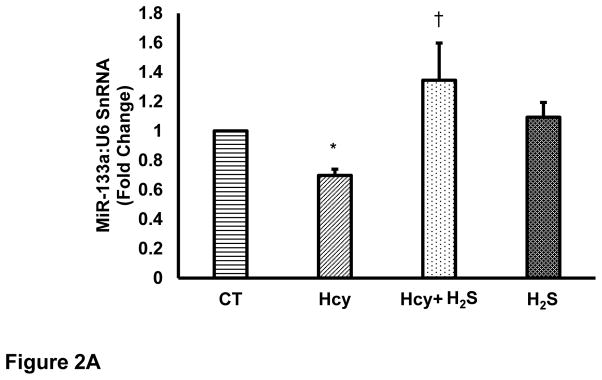

3.2. HHcy attenuates and H2S induces miR-133a in cardiomyocytes

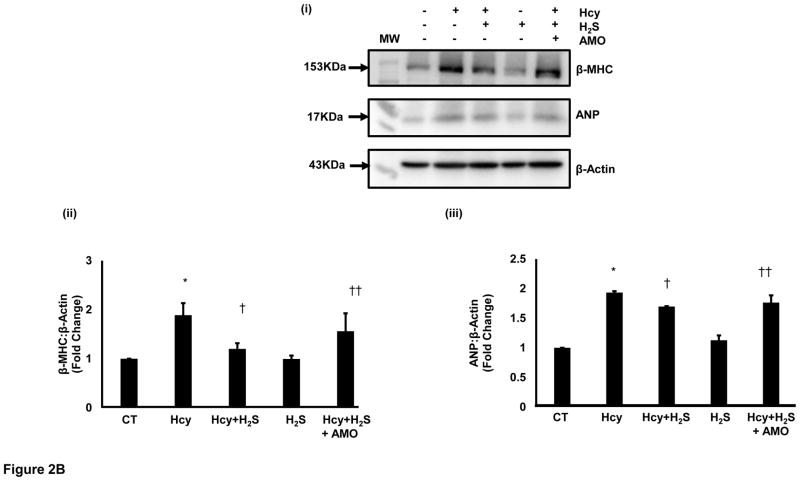

Since miR-133a is recognized as an anti-hypertrophy miRNA [24], and H2S is reported to induce miR-133a [30], we were interested to evaluate the effect of HHcy on miR-133a in cardiomyocytes. For that, we measured the levels of miR-133a in the above-mentioned four groups using individual miR-133a assay as described elsewhere [31]. The miR-133a assay revealed that HHcy down regulates miR-133a, whereas concomitant treatment with H2S induces miR-133a in the cardiomyocytes (Figure 2A). However, there was no significant difference between CT and H2S groups. One-way ANOVA showed significant difference in miR-133a among the four groups. These findings elucidate that HHcy inhibits miR-133a, which is ameliorated by H2S in cardiomyocytes. Since miR-133a inhibits hypertrophy [24], we were interested to understand whether the mitigation of HHcy mediated hypertrophy by H2S is due to up regulation of miR-133a. For that, we treated Hcy+ H2S with anti-miR-133a (AMO). If H2S inhibits HHcy mediated hypertrophy through induction of miR-133a, then treatment with AMO in Hcy+ H2S should blunt the anti-hypertrophic effect of H2S. We evaluated the levels of β-MHC and ANP in the five (four above and Hcy+ H2S+AMO) groups, which revealed that AMO treatment nullified the anti-hypertrophy effect of H2S in HHcy cardiomyocytes (Figure 2B). It suggests that miR-133a plays crucial role in H2S mediated mitigation of hypertrophy in HHcy cardiomyocytes. These results provide evidence that H2S inhibits Hcy mediated hypertrophy by inducing miR-133a in the cardiomyocytes.

Figure 2.

H2S mitigates Hcy mediated attenuation of miR-133a in the cardiomyocytes. Individual miR-133a assay in the four groups of HL1 cardiomyocytes: control (CT), homocysteine treated (Hcy), Hcy and H2S treated (Hcy+ H2S), and H2S treated (H2S). U6 is used as an endogenous control for miR-133a. Data represents expression in fold change (mean± S. E.) of miR-133a in treated samples compared to control (CT). Experiments repeated at least three times, N=7. *, p<0.05 as compared to CT; †, p<0.05 as compared Hcy. B. MiR-133a in H2S mediated recovery in HL1 cells treated with homocysteine (Hcy). B (i). Representative Western blot of β-MHC and ANP in different groups. β-actin is a loading control. HL1 cells treated with Hcy and Hcy+H2S for 24 hour and expression of ANP was analyzed. AMO-133a was transfected before Hcy+H2S treatment. B (ii). Bar graph shows densitometric analyses of β-MHC bands and represented as fold change of control. B (iii). Bar graph represents densitometric analyses of ANP bands and presented as fold change of control. N=3. *, p<0.05 as compared to CT; †, p<0.05 as compared Hcy; ††, p<0.05 as compared Hcy+H2S.

3.3 H2S augments miR-133a by activating MEF2C in HHcy cardiomyocytes

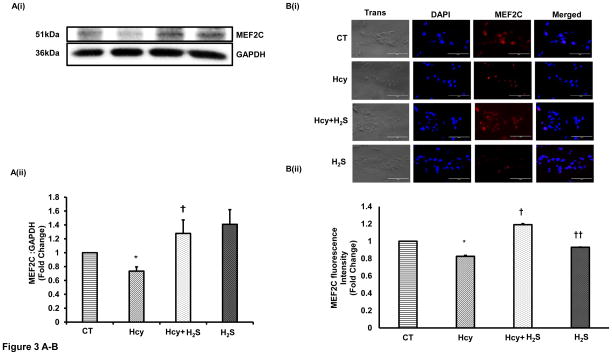

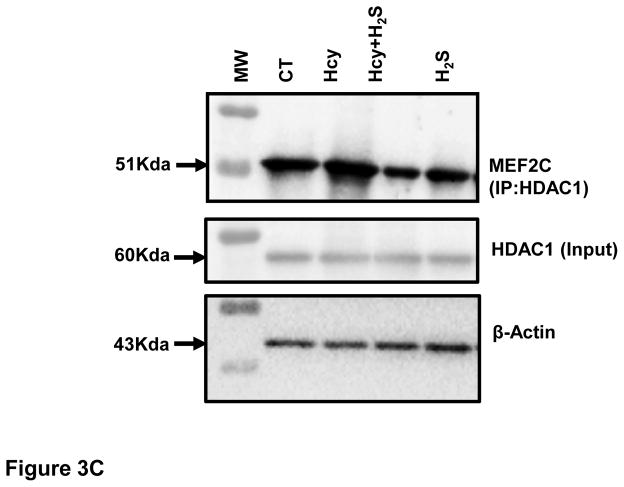

After showing that H2S induces miR-133a, we were interested to understand how H2S up regulated miR-133a in HHcy cardiomyocytes. To investigate the underlying mechanism, we first measured the protein and cellular levels of MEF2C- a transcriptional inducer of miR-133a [25] in the four groups. Our results show that HHcy down regulates whereas H2S induces MEF2C in HHcy cardiomyocytes at both protein and cellular levels (Figure 3A–B). However, there was no significant difference between CT and H2S group (Figure 3A–B). The significant increase in MEF2C in Hcy+H2S as compared to Hcy group suggests that H2S induces miR-133a by up regulating MEF2C in HHcy cardiomyocytes. Next, we determined whether the Hcy has any effect on activation of MEF2C. Since MEF2C remains inactivate if it binds to HDAC [26], we performed co-IP of MEF2C with HDAC1. The bound form of MEF2C with HDAC1 was evaluated by immunoprecipitation of HDAC1 (input) and probing it with MEF2C. The co-IP analyses revealed that the bound form of MEF2C (MEF2C-HDAC1) was robust in HHcy cardiomyocytes but dramatically decreased in Hcy+H2S (Figure 3C). To rule out unequal loading of proteins for co-IP, we separately performed Western blot with the same amount of protein and measured the levels of β-actin, which showed equal loading of proteins in the four groups (Figure 3C). To reinforce the co-IP results, we determined the cellular levels of MEF2C and HDAC1 in the four groups. The immunofluorescence results show that HDAC1 was up regulated in Hcy as compared to CT, and mitigated in Hcy+ H2S (Figure 3D(i)). The cellular expression of MEF2C was less in Hcy but elevated in Hcy+H2S. Interestingly, co-localization of MEF2C with HDAC1 revealed that the number of cells expressing both HDAC1 and MEF2C was comparatively higher in Hcy group (Figure 3D(i)). To evaluate the co-expression of MEF2C with HDAC1, we determined the ratio of MEF2C with HDAC1 in the four groups. If the HDAC1 level is higher than MEF2C, there will be more probability of bound (MEF2C-HDAC1) or inactive form of MEF2C. The fluorescence analyses showed that in Hcy group MEF2C/HDAC1 was decreased than that of CT indicating that HHcy induces the formation of MEF2C-HDAC1 complex. On contrary, treatment with H2S increased MEF2C and decreased HDAC1, thereby increasing the ratio of MEF2C/HDAC1 and decreasing the bound form of MEF2C in HHcy cardiomyocytes (Figure 3D(i)–(ii)). These results demonstrate that HHcy attenuates miR-133a by inhibiting MEF2C, whereas H2S up regulates miR-133a by inducing MEF2C in HHcy cardiomyocytes.

Figure 3.

H2S induces expression and activity of MEF2C expression in HHcy HL1 cardiomyocytes. A (i). Representative Western blot of MEF2C in the four groups. GAPDH is a loading control. A (ii). Bar graph shows densitometric analyses of MEF2C bands and represented as fold change of control. B (i). Immunofluorescence of MEF2C in HL1 cells treated with homocysteine (Hcy), H2S donor (Na2S) and Hcy+H2S. Red color represents MEF2C and blue color shows DAPI. Scale bar: 100μm. (ii) Bar graph shows quantitative analyses of color and represented as mean ± S. E. C. Co-Immunoprecipitation of MEF2C with HDAC in cell lysate of HL1 cells treated with homocysteine (Hcy), H2S donor (Na2S) and Hcy+H2S. Immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-HDAC1 antibody and Western blotting was performed for MEF2C. Input was electrophoresed in a separate gel and developed for β-actin. D (i). Immunofluorescence showing co-localization of MEF2C with HDAC1 in the four groups of HL1 cardiomyocytes. Red color represents MEF2C, green color HDAC1, and blue color DAPI (nucleus). D (ii). Bar graph shows quantitative analysis of MEF2C/HDAC1 immunofluorescence intensity in the above groups and represented as mean± S. E. Scale bar: 100μm. N=3. *, p<0.05 compared to CT; †, p<0.05 compared Hcy; ††, p<0.05 compared Hcy+H2S.

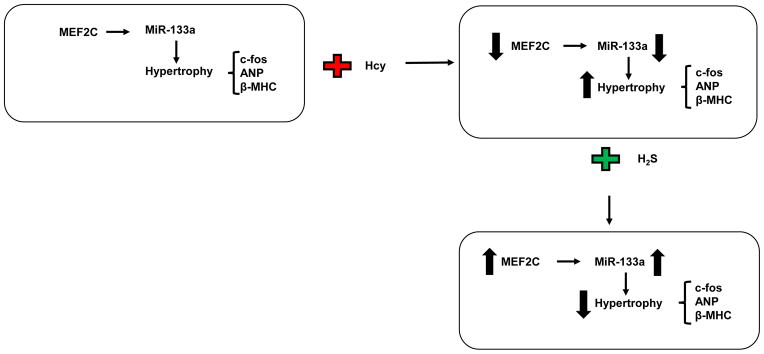

Overall, our results show that HHcy down regulates and inactivates MEF2C causing attenuation of miR-133a, which induces hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes. On contrary, H2S up regulates and activates MEF2C, and increases the level of miR-133a that mitigates HHcy mediated hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A schematic representation showing cardioprotective mechanism of H2S in Hcy induced hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes. Elevated level of Hcy causes hypertrophy by increasing the level of c-fos, ANP, and β-MHC; and decreasing the level of miR-133a in cardiomyocytes. H2S treatment induces MEF2C that in turn up regulates miR-133a, which alleviates c-fos, ANP, and β-MHC; and ultimately mitigates hypertrophy.

4. Discussion

We demonstrate a novel mechanism of Hcy mediated inhibition of miR-133a and induction of hypertrophy, and H2S mediated mitigation of hypertrophy in HHcy cardiomyocytes (Figure 4). Hcy is reported to play crucial role in pathological cardiac remodeling [2, 3, 5, 18, 32–34]. However, there is debate on whether Hcy is a cause or effect of cardiovascular diseases [27]. The negative results of clinical trials, where lowering Hcy level by folic acid supplements did not improve the conditions in heart failure patients poses a major setback on HHcy being a cause for heart failure [35–37]. Additionally, the underlying molecular mechanisms that elicit the causative role of Hcy in the heart disease is poorly understood [38]. Our results demonstrate that HHcy induces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by suppressing miR-133a, which show a causative role of Hcy in pathological remodeling of the heart. Further, we provided a detailed mechanism by which Hcy down regulates miR-133a. HHcy inactivates and down regulates MEF2C in the cardiomyocytes (Figure 3A–C). Since miR-133a is attenuated in the failing human hearts [24] and in diabetic hearts [22, 28], and its role is established as anti-hypertrophy [24, 39] and anti-fibrosis [22, 23], our results suggest a new role of Hcy in miR-133a mediated pathological remodeling in the heart, which is relevant to the human heart failure.

H2S is a metabolic product of Hcy [7]. Mutation of cystathionine beta-synthase or cystathionine gamma- lyase genes or enzymatic inactivation of these proteins impairs the endogenous production of H2S [7]. H2S is emerged as a novel cardioprotective gas with therapeutic potential for heart diseases [8, 10, 11, 40]. It has multifaceted role such as vasorelaxant [41], inducer of anti-stress AKT [42, 43], preserver of mitochondrial function [12], and inhibitor of hypertrophy and fibrosis [44]. H2S also mitigates Hcy mediated induction of oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress [45]. Since HHcy can be caused due to inhibition of metabolic enzymes that produce H2S from Hcy [7], one of the fundamental question could be whether the inhibition of H2S production is the major cause of HHcy mediated cardiovascular diseases. To answer this question, we treated cardiomyocytes with both Hcy and H2S concomitantly. Our results show that treatment of H2S mitigates the hypertrophic effect of Hcy (Figure 1A–C) supporting the notion that inhibition of H2S production in HHcy cardiomyocytes leads to hypertrophy. Since H2S is reported to mitigate phenylephrine mediated hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes [30], we also measured the levels of miR-133a in HHcy cardiomyocytes treated with and without H2S. Our results show that H2S mitigates Hcy mediated attenuation of miR-133a in cardiomyocytes (Figure 2) suggesting that effect of HHcy is alleviated by H2S in cardiomyocytes. Our results also support the anti-hypertrophic effect of H2S in cardiomyocytes [30]. To get insight into how Hcy suppresses and H2S induces miR-133a, we measured the levels of MEF2C, a known inducer of miR-133a [25] in HHcy cardiomyocytes treated with and without H2S. Interestingly, we observed that Hcy inactivates MEF2C by promoting the binding of MEF2C with HDAC1 in cardiomyocytes. On contrary, H2S treatment mitigates binding of MEF2C with HDAC1 releasing more MEF2C that in turn increases transcription of miR-133a in HHcy cardiomyocytes. To our knowledge this is first study showing the mechanism of Hcy and H2S mediated regulation of miR-133a transcription in cardiomyocytes. These findings also suggest that inhibition of H2S could be the major cause of HHcy mediated pathological remodeling, and supplement of H2S could be a major therapeutic strategy to ameliorate Hcy mediated cardiovascular pathology.

Hypertrophy is marker for cardiac pathogenesis [46]. Our results show that c-fos, an early marker of hypertrophy [47] is up regulated in HHcy cardiomyocytes, and mitigated by H2S in HHcy cardiomyocytes (Figure 1A). Our results are consistent with the previous report showing that HHcy induces c-fos in hepatocytes [48]. HHcy is also reported to induce left ventricular (LV) to body weight ratio, which is an indicator of cardiac hypertrophy [49]. Our results show up regulation of β-MHC and ANP- late markers of cardiac hypertrophy in HHcy cardiomyocytes (Figure 1B–D) supporting HHcy mediated induction of LV hypertrophy. It is documented that H2S mitigates cardiac hypertrophy in pathological hearts [44, 50], which is consistent with our results, where H2S mitigates Hcy mediated hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes (Figure 1A–D). The anti-hypertrophic effect of miR-133a is due to its regulatory effect on RhoA and CDC42, which are involved in cytoskeletal and myofibrillar arrangements during cardiac hypertrophy [24]. One of the key molecules involved in regulation of cardiac remodeling is connective tissue growth factor (CTGF). CTGF regulates collagens synthesis by inducing fibroblast and is a direct target of miR-133a [51]. In cardiomyocytes, knockdown of miR-133a robustly increased the mRNA and protein levels of CTGF, which is blunted by overexpression of miR-133a [51]. Our results show that Hcy induces hypertrophy by suppressing miR-133a, whereas H2S mitigates hypertrophy by inducing miR-133a in HHcy cardiomyocytes. The cardioprotective effect of H2S is also mediated through miR-21, which attenuates myocardial ischemic and inflammatory injury in mice [52].

In conclusion, our findings provide new insight on Hcy mediated down regulation and inactivation of MEF2C, attenuation of miR-133a, and induction of hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes. It also suggests that the pathophysiology of HHcy is attributed to the decreased levels of H2S, and H2S has therapeutic potential for HHcy pathogenesis. Our findings also provide a novel mechanism of H2S mediated induction of miR-133a in cardiomyocytes.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from National Institute of Health grants: HL-113281and HL-116205 to Paras K. Mishra is gratefully acknowledged. We would like to thank Bryan T Hackfort, a member of our laboratory for editing the final version of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- HHcy

Hyperhomocysteinemia

- H2S

Hydrogen sulfide

- Hcy

Homocysteine

- ANP

atrial natriuretic peptide

- β-MHC

beta-myosin heavy chain

- MEF2C

myosin specific enhancer factor 2c

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Authors declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ganguly P, Alam SF. Role of homocysteine in the development of cardiovascular disease. Nutr J. 2015;14:6. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-14-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCully KS. Homocysteine and the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2015:1–9. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2015.1010516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nygard O, Nordrehaug JE, Refsum H, Ueland PM, Farstad M, Vollset SE. Plasma homocysteine levels and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:230–236. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707243370403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCully KS. Homocysteine and vascular disease. Nat Med. 1996;2:386–389. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra PK, Tyagi N, Kundu S, Tyagi SC. MicroRNAs are involved in homocysteine-induced cardiac remodeling. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2009;55:153–162. doi: 10.1007/s12013-009-9063-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vacek TP, Sen U, Tyagi N, Vacek JC, Kumar M, Hughes WM, et al. Differential expression of Gs in a murine model of homocysteinemic heart failure. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:79–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sen U, Mishra PK, Tyagi N, Tyagi SC. Homocysteine to hydrogen sulfide or hypertension. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2010;57:49–58. doi: 10.1007/s12013-010-9079-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barr LA, Calvert JW. Discoveries of hydrogen sulfide as a novel cardiovascular therapeutic. Circ J. 2014;78:2111–2118. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-14-0728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calvert JW, Elston M, Nicholson CK, Gundewar S, Jha S, Elrod JW, et al. Genetic and pharmacologic hydrogen sulfide therapy attenuates ischemia-induced heart failure in mice. Circulation. 2010;122:11–19. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.920991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavu M, Bhushan S, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide-mediated cardioprotection: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011;120:219–229. doi: 10.1042/CS20100462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel VB, McLean BA, Chen X, Oudit GY. Hydrogen sulfide: an old gas with new cardioprotective effects. Clin Sci (Lond) 2015;128:321–323. doi: 10.1042/CS20140668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, Doeller JE, Kraus DW, Tao L, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15560–15565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu Z, Peng H, Du Q, Lin W, Liu Y. GYY4137, a hydrogen sulfidereleasing molecule, inhibits the inflammatory response by suppressing the activation of nuclear factorkappa B and mitogenactivated protein kinases in Coxsackie virus B3infected rat cardiomyocytes. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:1837–44. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barr LA, Shimizu Y, Lambert JP, Nicholson CK, Calvert JW. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates high fat diet-induced cardiac dysfunction via the suppression of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nitric Oxide. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.12.013. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calvert JW, Jha S, Gundewar S, Elrod JW, Ramachandran A, Pattillo CB, et al. Hydrogen sulfide mediates cardioprotection through Nrf2 signaling. Circ Res. 2009;105:365–374. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King AL, Polhemus DJ, Bhushan S, Otsuka H, Kondo K, Nicholson CK, et al. Hydrogen sulfide cytoprotective signaling is endothelial nitric oxide synthase-nitric oxide dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:3182–3187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321871111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mishra PK, Givvimani S, Metreveli N, Tyagi SC. Attenuation of beta2-adrenergic receptors and homocysteine metabolic enzymes cause diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;401:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyagi AC, Sen U, Mishra PK. Synergy of microRNA and stem cell: a novel therapeutic approach for diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2011;7:367–376. doi: 10.2174/157339911797579179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leptidis S, El AH, Lok SI, de WR, Olieslagers S, Kisters N, et al. A deep sequencing approach to uncover the miRNOME in the human heart. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hedley PL, Carlsen AL, Christiansen KM, Kanters JK, Behr ER, Corfield VA, et al. MicroRNAs in cardiac arrhythmia: DNA sequence variation of MiR-1 and MiR-133A in long QT syndrome. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2014;74:485–491. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2014.905696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen S, Puthanveetil P, Feng B, Matkovich SJ, Dorn GW, Chakrabarti S. Cardiac miR-133a overexpression prevents early cardiac fibrosis in diabetes. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:415–421. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matkovich SJ, Wang W, Tu Y, Eschenbacher WH, Dorn LE, Condorelli G, et al. MicroRNA-133a protects against myocardial fibrosis and modulates electrical repolarization without affecting hypertrophy in pressure-overloaded adult hearts. Circ Res. 2010;106:166–175. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.202176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Care A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, Bonci D, Addario A, Gallo P, et al. MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2007;13:613–618. doi: 10.1038/nm1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu N, Williams AH, Kim Y, McAnally J, Bezprozvannaya S, Sutherland LB, et al. An intragenic MEF2-dependent enhancer directs muscle-specific expression of microRNAs 1 and 133. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20844–20849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710558105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nebbioso A, Manzo F, Miceli M, Conte M, Manente L, Baldi A, et al. Selective class II HDAC inhibitors impair myogenesis by modulating the stability and activity of HDAC-MEF2 complexes. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:776–782. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brattstrom L, Wilcken DE. Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease: cause or effect? Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:315–323. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chavali V, Tyagi SC, Mishra PK. Differential expression of dicer, miRNAs, and inflammatory markers in diabetic Ins2+/− Akita hearts. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;68:25–35. doi: 10.1007/s12013-013-9679-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maron BA, Loscalzo J. The treatment of hyperhomocysteinemia. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:39–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.041807.123308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, Hao DD, Zhang JS, Zhu YC. Hydrogen sulphide inhibits cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by up-regulating miR-133a. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;413:342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.08.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chavali V, Tyagi SC, Mishra PK. MicroRNA-133a regulates DNA methylation in diabetic cardiomyocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;425:668–672. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cattaneo M. Hyperhomocysteinemia, atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 1999;81:165–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jager A, Kostense PJ, Nijpels G, Dekker JM, Heine RJ, Bouter LM, et al. Serum homocysteine levels are associated with the development of (micro)albuminuria: the Hoorn study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:74–81. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mishra PK, Tyagi N, Sen U, Joshua IG, Tyagi SC. Synergism in hyperhomocysteinemia and diabetes: role of PPAR gamma and tempol. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2010;9:49. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonaa KH, Njolstad I, Ueland PM, Schirmer H, Tverdal A, Steigen T, et al. Homocysteine lowering and cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1578–1588. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marti-Carvajal AJ, Sola I, Lathyris D, Salanti G. Homocysteine lowering interventions for preventing cardiovascular events. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD006612. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006612.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lonn E, Yusuf S, Arnold MJ, Sheridan P, Pogue J, Micks M, et al. Homocysteine lowering with folic acid and B vitamins in vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1567–1577. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vizzardi E, Bonadei I, Zanini G, Frattini S, Fiorina C, Raddino R, et al. Homocysteine and heart failure: an overview. Recent Pat Cardiovasc Drug Discov. 2009;4:15–21. doi: 10.2174/157489009787259991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng B, Chen S, George B, Feng Q, Chakrabarti S. miR133a regulates cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26:40–49. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martelli A, Testai L, Breschi MC, Blandizzi C, Virdis A, Taddei S, et al. Hydrogen sulphide: novel opportunity for drug discovery. Med Res Rev. 2012;32:1093–1130. doi: 10.1002/med.20234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang G, Wu L, Jiang B, Yang W, Qi J, Cao K, et al. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science. 2008;322:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1162667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cai WJ, Wang MJ, Moore PK, Jin HM, Yao T, Zhu YC. The novel proangiogenic effect of hydrogen sulfide is dependent on Akt phosphorylation. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tamizhselvi R, Sun J, Koh YH, Bhatia M. Effect of hydrogen sulfide on the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-protein kinase B pathway and on caerulein-induced cytokine production in isolated mouse pancreatic acinar cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:1166–1177. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.150532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang J, Wang D, Zheng J, Huang X, Jin H. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis induced by abdominal aortic coarctation in rats. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:923–928. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang L, Geng B, Yu F, Zhao J, Jiang H, Du J, et al. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits myocardial injury induced by homocysteine in rats. Amino Acids. 2008;34:573–585. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vikstrom KL, Bohlmeyer T, Factor SM, Leinwand LA. Hypertrophy, pathology, and molecular markers of cardiac pathogenesis. Circ Res. 1998;82:773–778. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.7.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carreno JE, Apablaza F, Ocaranza MP, Jalil JE. Cardiac hypertrophy: molecular and cellular events. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2006;59:473–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woo CW, Siow YL, OK Homocysteine induces monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in hepatocytes mediated via activator protein-1 activation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1282–1292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707886200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pal SA, Kaur T, SinghDahiya R, Singh N, Singh Bedi PM. Ameliorative role of rosiglitazone in hyperhomocysteinemia-induced experimental cardiac hypertrophy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2010;56:53–59. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181de308b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Snijder PM, de Boer RA, Bos EM, van den Born JC, Ruifrok WP, Vreeswijk-Baudoin I, et al. Gaseous hydrogen sulfide protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice partially independent from hypometabolism. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duisters RF, Tijsen AJ, Schroen B, Leenders JJ, Lentink V, van d MI, et al. miR-133 and miR-30 regulate connective tissue growth factor: implications for a role of microRNAs in myocardial matrix remodeling. Circ Res. 2009;104:170–178. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toldo S, Das A, Mezzaroma E, Chau VQ, Marchetti C, Durrant D, et al. Induction of microRNA-21 with exogenous hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemic and inflammatory injury in mice. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014;7:311–320. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]