Abstract

Objective

Observational studies show that when a depressed mother’s symptoms remit, her children’s symptoms decrease. Without random assignment of mother’s treatment, we cannot conclude that the child’s improvement is due to the mother’s treatment. The objective is to determine the differential effects of a depressed mother’s treatment on her child.

Methods

Randomized double-blind 12-week clinical trial of escitalopram, bupropion, or the combination in depressed mothers (N=76), and independent assessment of their children (N=135) ages 7–17 years. We hypothesized that mothers on combination treatment would have significantly earlier onset and higher rate of remission than on either monotherapy. The mothers’ outcome would be reflected in their children.

Results

There were no significant treatment differences in mothers’ depressive symptoms or remission. However, children’s depressive symptoms and functioning improved significantly if their mothers received escitalopram (vs. bupropion and combination). Only in the escitalopram group was significant improvement of mother’s depression associated with improvement in the child’s symptoms. Exploratory analyses suggested that this may be due to changes in parental functioning: Mothers on escitalopram (vs. bupropion and combination) reported significantly greater improvement in their ability to listen and talk to their children, who as a group reported that their mothers were more caring over the 12 weeks. Mother’s baseline negative affectivity appeared to moderate the effect of mother’s treatment on children, although the effect was not statistically significant. Children of mothers with low negative affectivity improved on all treatments. Children of mothers with high negative affectivity improved significantly only if the mother was on escitalopram (vs. bupropion and combination).

Conclusions

The effects of the depressed mother’s improvement on her children may depend on her type of treatment. Depressed mothers with high anxious distress and irritability may require medications that reduce these symptoms in order to show the effect of her remission on her children.

INTRODUCTION

There are no published exceptions that the school-aged offspring of mothers with major depression (MDD) have increased rates of depression.1–7 We and others previously found that the remission of maternal depression is associated with reduction of their offspring’s psychiatric symptoms.8–11 These studies were observational, and treatment of mothers was not randomly assigned. We could not conclude that the improvement in the child’s symptoms was due to the mother’s treatment.

A nine-month randomized controlled study of 47 depressed mothers receiving interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) or treatment as usual (TAU), and their children ages 6–18 years,12 found that the mother’s improvement on IPT was statistically significant at 12 weeks. The treatment effects on children were significant at 9 months. Two other randomized controlled clinical trials testing the effects of maternal treatment on children included much younger children (ages 2–4 and 4–11), and found that there were no statistically significant treatment effects on children.13,14

We independently assessed children of depressed mothers participating in a randomized, double-blind clinical trial testing the effects of escitalopram, bupropion, or the combination for 12 weeks.15 We hypothesized that mothers on combination treatment would have an earlier onset and higher rate of remission than either monotherapy and that the results would be reflected in their children.

METHODS

Adult Study participants were psychiatric outpatients aged 18–65 with non-psychotic major depression, and without a lifetime history of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or a current substance use disorder. Patients with current medical and psychiatric conditions, except as noted above, were included unless a medication was contraindicated.

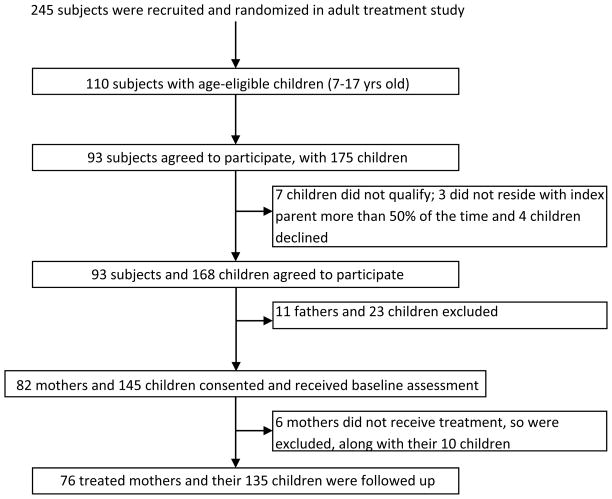

Parents were eligible for the Child Study if they participated in the Adult Study and had at least one child aged 7–17 years old who lived at least half of the time with the treated parent and had no developmental disability that would preclude participation. All eligible parents and children were enrolled. Among the 245 randomized adults, 110 (44.9%) had age-eligible children and 93 (84.5%) eligible parents entered the Child Study (Figure 1). Ninety-three parents (82 mothers and 11 fathers) had 175 age-eligible children of whom 168 children (96%) participated in the Child Study. This report is limited to mothers. Seventy-six (92%) of the 82 eligible mothers and 135 (93%) of their 145 children entered the study and comprise the reported cohort. There were no age or baseline Hamilton score differences between the six women not enrolled in the study and the women enrolled.

Figure 1.

STAR*D-2 Flowchart

Children were not excluded if they were in treatment and were referred if requested. The protocol, approved by the institutional review boards, took place in New York City and Ottawa, Canada. Each site had two clinics under the direction of the principal investigator, with the same protocol and IRB.

Adult Study

Mothers received a battery of assessments by the Adult Study team at baseline, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 weeks. The mother’s diagnosis was established by the Schedule for Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Diagnoses, Axis I, Patient Version (SCID-IV-I/P).16 The severity of depressive symptoms was estimated with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-17).17 Remission was a score of ≤7. Relapse was ≥14 after remission.18

The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report (QIDS-SR), a self-report measure designed to assess the severity of depressive symptoms, which can be transformed to HAMD-17 scores,19 was used if a mother missed a HAMD-17 rating. This occurred with five mothers in week 4, six in week 8, and seven in week 12, and did not vary by maternal treatment.

The Montgomery Asberg Rating Scale (MADRS),20 a 10-item instrument with severity on a scale ranging from 0 to 6 (higher = greater severity), was used.

The Social Adjustment Scale Self-Report (SAS-SR) assessed performance in work, social and leisure activities, extended family, marital role, and parental role.21,22 Parenting questions include: interest in child activities, ability to talk and listen to your child, getting along with, and feeling affection towards your child.

Nutt and Stahl23,24 have reported that high negative affect () might result from serotonin deficiency. Gerra et al.,25 based on the Adult Study, developed a negative affectivity score and hypothesized that patients with high negative affectivity would preferentially respond to selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRI’s). Negative affectivity was composed of items from the HAM-D17, MADRS, QIDS-SR, and SAS-SR and included three dimensions: guilt, hostility/irritability, and fear/anxiety (see eMethods). Because of the different ranges of item scores, the variables were recoded into a 7-point scale. The mean affect scores were used, and negative affectivity was derived by summing the three dimension scores. The sample median (2.10) was used to split into low and high negative affectivity.

Medication side effects were recorded on a checklist at each appointment. The escitalopram dose ranged from 10 mg to 40 mg and the bupropion dose from 150 mg to 450 mg. Treating physicians were encouraged to reach doses of 40 mg for escitalopram and 450 mg for bupropion, in order to maximize the effect of treatment (see 15 for details). To maintain the blind, medication and placebo looked identical, and the same number were used for each treatment. The dose of escitalopram over 20 mg is higher than FDA recommendations. The study was designed before these guidelines.

Child Study

The Child Study assessments were conducted by independent assessors who knew that participating mothers were depressed but did not have access to their Adult Study assessments. Children were assessed at baseline, 4, 8, and 12 weeks.

Children’s psychiatric disorders were established by independent interviews of mothers and children using the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, Present and Lifetime Measures (K-SADS-PL).26 Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 27-item self-report Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) with values from 0 to 2 (symptom present).27,28 Children’s functioning was assessed by the child version of the Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS).29

Children’s perception of their mothers’ parenting was assessed with the self-report Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI).30 The 12-item dimension of care and affection (eTable 5) was used to replicate findings of Garber et al.11

Mental health treatment received by the child historically at baseline and during the 12 weeks was recorded. Six interviewers with prior child clinical experience received assessment training under the supervision of child psychiatrists (DJP, MFF) and completed the child assessments (see eMethods).

Data Analysis

Difference in means of continuous variables by treatment for mother’s baseline characteristics were determined using analysis of variance; differences in categorical variables by treatment were analyzed using contingency table analyses and associated χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests when expected counts were low. Differences in children’s baseline characteristics by treatment were analyzed using linear mixed models for continuous variables and logistic regression analyses in the context of generalized estimating equations31 for categorical variables, to enable adjustment for correlation between siblings. Baseline characteristics found to be significantly different were adjusted for in subsequent analyses.

Differences in rates of maternal remission from depression during the 12 weeks by treatment assignment were determined using logistic regression analysis as follows: Maternal remission status was the binary outcome variable; treatment assignment, represented by two dummy variables, was considered as the set of independent variables; and age of mother as well as other baseline demographic and clinical characteristics that had been previously shown to have significant differences in distribution by treatment assignment, were also included as potential confounding variables. Differential effects of treatment on change in mother’s depressive symptoms and functioning were analyzed using linear mixed effects regression analyses, which account for the nesting of time within person, to test linear and curvilinear (quadratic) trends over time and their interaction with treatment.

The differential effect of maternal treatments on child outcomes was investigated as follows: Model 1: When the child outcome was a continuous variable, linear mixed effects models were fitted to the data with child outcome as the dependent variable, maternal treatment status and time (study week) as independent variables, and an interaction term representing treatment × time. In addition, age and sex of child and study site were included as covariates. Other child and maternal baseline characteristics that were significantly different between treatments were also tested, but were dropped from the model if they did not contribute to an appreciable difference in the results. A statistically significant interaction term indicated a differential treatment effect. Correlations between related measures over time, as well as non-independence of observations among siblings, were handled by including nested random effects in the model, i.e., within-subject observations nested within family.32 When child outcomes were binary variables (child diagnoses) or count variables (child symptoms), logistic random effects regression models (for binary outcomes) and Poisson random effects regression (for outcomes that are counts) were used to determine differential effects of maternal treatment on these outcomes.33 Repeated measures over time and non-independence of siblings as well as potential confounding variables were handled as described for continuous outcomes.

For child outcomes that showed statistically significant differences in trend parameters over time, we investigated whether differential effects of changes in mother’s depressive symptoms over time could explain (i.e., mediated) these differences. Using Model 2: Including mother’s depressive symptoms as time-varying covariates in models with relevant child outcomes as dependent variables, and maternal treatment effects as the independent variables, we tested for main effects and/or interactions of mother’s depressive symptoms over time by treatment, including a main effect for treatment in the models that we used to estimate the effect of mother’s treatment on child outcomes implicitly controlled for baseline differences by treatment (if any).34 Exploratory analyses of the potential moderating effect of mother’s baseline Negative Affect on the patterns of differential effects of mother’s treatment on child outcomes (if any) were conducted by including main effects and two- and three-way interaction terms for negative affectivity (coded as a binary variable) and time, treatment, and time × treatment in Model 1.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Depressed Mothers and their Children by Maternal Treatment

There were no significant differences in mothers’ or children’s demographic or clinical characteristics at baseline by maternal treatment, with the following exceptions. Mothers receiving combination treatment were older than those receiving the other two treatments (p=0.003), and 20% of mothers treated with bupropion were married or cohabitating, as compared to approximately 52% of mothers who received either escitalopram or combination treatment. A significantly lower proportion of children of mothers on bupropion were females (p<0.001). There were no differences in children’s depressive symptom (CDI) or impairment (CIS) scores, or current or lifetime diagnosis at baseline. Analyses of both mother’s and children’s outcomes were adjusted for these demographic differences (see eTable 1).

Maternal Outcomes by Treatment

The overall rate of maternal remission during the 12 weeks following treatment initiation was high (67%) and did not vary by treatment (χ2=2.36, df=2, p=0.31). The relapse rates were low and did not vary by treatment: only 7 mothers of 15 children relapsed over the 12 weeks (eTables 2 and 3).

The results of fitting a mixed effects regression model with linear and quadratic terms to estimate changes in maternal depression symptoms over time by maternal treatment appear in eFigure 1. Both linear and quadratic terms were found to be significant but did not vary significantly with treatment. Taken together, the negative linear component (Beta1=−2.62, SE=0.17, t=−15.22, p<0.001) and the positive quadratic component (Beta2=0.14, SE=0.01, t=9.85, p<0.001) suggest that maternal HAMD-17 scores decreased significantly and then leveled off for all treatments over the 12 weeks.

Child Outcomes by Maternal Treatment Over 12 Weeks after Treatment Initiation

We compared child outcomes by maternal treatment adjusting for child’s age and gender, within-family correlation, and study site over the 12 weeks. Statistically significant differential treatment effects were shown on the CDI and the CIS. Additional models were tested which included maternal baseline characteristics that were significantly different between treatment groups (i.e., age and marital status); these additional variables did not confound results or qualify as moderators thus were subsequently omitted from the analyses.

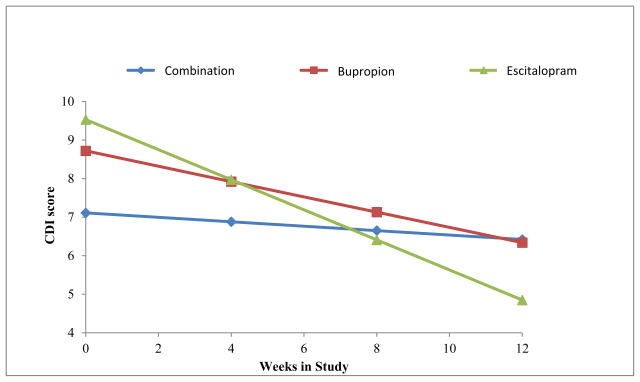

We first determined whether there were significant changes among child outcomes in each of the maternal treatments separately during the 12 weeks. Table 1 shows that there was a statistically significant decrease over time in mean CDI scores among children of bupropion- and escitalopram-treated mothers (reflected in the negative beta coefficients and associated p values), indicating that children whose mothers were treated with bupropion or escitalopram became less depressed over time, and those whose mothers were treated with the combination did not. The group-by-time interaction was significant (F=7.28, df=2, 227, p<0.001), suggesting a difference in treatment effect. Post hoc tests revealed that the time trend for children of escitalopram mothers was statistically different from those of combination (t=3.81, p<0.001) and bupropion (t=2.04, p=0.04) mothers. There were no significant differences between combination and bupropion (t=1.51, p=0.13) (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Time Trends for Child Reported Symptoms and Impairment by Maternal Treatment Assignment: Baseline to 12 weeksa

| Outcome | N=76 mothers, 135 childrenb

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Beta | SE | p | Change over time | |

| Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Scores | |||||

|

| |||||

| Bupropion | 8.6 | −0.20 | 0.07 | 0.006 | −2.38 |

| Escitalopram | 10.5 | −0.39 | 0.06 | <0.0001 | −4.68 |

| Combination treatment | 7.2 | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.35 | −0.68 |

| Group-by-time | F=7.28 | 0.0009 | |||

| Pairwisec | |||||

| Bupropion vs escitalopram | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.04 | ||

| Combination vs bupropion | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.13 | ||

| Combination vs escitalopram | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.0002 | ||

|

| |||||

| Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS) Scores | |||||

|

| |||||

| Bupropion | 10.6 | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.62 | −0.53 |

| Escitalopram | 12.6 | −0.44 | 0.08 | <0.0001 | −5.22 |

| Combination | 10.2 | −0.19 | 0.07 | 0.01 | −2.27 |

| Group-by-time | F=5.57 | 0.004 | |||

| Pairwised | |||||

| Bupropion vs escitalopram | 0.39 | 0.12 | 0.001 | ||

| Combination vs bupropion | −0.15 | 0.12 | 0.22 | ||

| Combination vs escitalopram | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.03 | ||

All analyses were adjusted for child age (centered) and gender, site, and within-family correlation.

N=54 children of 27 combination-treated mothers, 35 children of 20 bupropion-treated mothers, and 46 children of 29 escitalopram-treated mothers.

Post hoc tests revealed that the time trend for children of escitalopram-treated mothers was statistically different from those of either combination- (t=3.81, p=0.0002) or bupropion-treated (t=2.04, p=0.04) mothers. There were no differences between combination treatment and bupropion (t=1.51, p=0.13).

Post hoc tests revealed that the time trend for children of escitalopram-treated mothers was statistically different from those of either combination- (t=2.25, p=0.03) or bupropion-treated (t=3.25, p=0.001) mothers. There were no differences between combination treatment and bupropion (t=−1.24, p=0.22).

Figure 2. Estimated Trends in Mean Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Scores Over 12 Weeks by Maternal Treatment Assignment.

Note. Figure shows means for 54 children of 27 combination-treated mothers, 35 children of 20 bupropion-treated mothers, and 46 children of 29 escitalopram-treated mothers. Lower scores indicate improvement. All analyses were adjusted for child age (centered) and gender, site, and within-family correlation. Time trends by treatment imply that children of escitalopram-treated mothers improved the most (Beta=−0.39, SE=0.06, t=−6.27, p<0.0001), followed by children of bupropion- (Beta=−0.20, SE=0.07, t=−2.82, p=0.006) and combination-treated mothers (Beta=−0.06, SE=0.06, t=−0.93, p=0.36). The overall week × treatment interaction was statistically significant (F=7.28, df= 2,227, p<0.001), implying that the change in child depression score over time differed significantly between treatment groups. Pairwise comparisons showed significant differences between children of mothers on combination vs. escitalopram treatment (Beta=0.33, SE=0.09, t=3.81, p=0.0002) and bupropion vs. escitalopram treatment (Beta=0.19, SE=0.09, t=2.04, p=0.04), and no significant differences between children of mothers on combination vs. bupropion treatment (Beta=−0.14, SE=0.09, t=1.51, p=0.13).

There was a statistically significant decrease over time in mean CIS scores among children of combination- and escitalopram-treated mothers (Table 1), indicating that these children became less impaired over time, as reflected in the statistically significant group-by-time interaction (F=5.57, df=2,238, p=0.004). Post hoc tests revealed that the time trend for children of mothers on escitalopram was statistically different from those of both combination (t=2.25, p=0.03) and bupropion (t=3.25, p=0.001) treated mothers. There were no significant differences between combination and bupropion (t=−1.24, p=0.22) (eFigure 2).

Changes in Maternal Depressive Symptoms and Treatment Effects on Child Outcomes

Tables 2a and 2b show results of the analysis to determine the relation between the changes in maternal depressive symptoms over time and the observed effect of treatment on Child Depressive Inventory (CDI) scores. Analyses reported in these tables are based on subjects with HAMD-17 data. Table 2a shows models where the main predictors are maternal treatment assignment, time, and their interaction; and Table 2b shows models where mothers’ HAMD-17 scores were added as a main predictor, along with interactions among HAMD-17 scores, treatment assignment, and time.

Table 2a.

Effect of Maternal Treatment Assignment on Trends in Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Outcome Over 12 Weeks

| Predictors | Betaa | SE | p | Overall p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week | −0.40 | 0.06 | <.0001 | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Treatment | 0.097 | |||

|

| ||||

| Bupropion | −0.71 | 1.37 | 0.60 | |

| Combination | −2.55 | 1.21 | 0.04 | |

| Escitalopram (reference) | – | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| Week × Treatment | 0.0007 | |||

|

| ||||

| Week × bupriopion | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.03 | |

| Week × combinaton | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.0001 | |

| Week × escitalopram (reference) | – | – | – | |

Note. All analyses were adjusted for child age (centered) and gender, site, and within-family correlation, and were restricted to subjects with HAMD17 data.

Beta denotes regression coefficient corresponding to specific effect.

Table 2b.

Explaining Maternal Treatment Effect on Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Outcome Over 12 Weeks

| Predictors | Does HAMD-17 effect vary by treatment? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Betaa | SE | p | Overall p | |

| Week | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.57 | 0.63 |

|

| ||||

| Treatment | 0.003 | |||

|

| ||||

| Bupropion | 5.73 | 2.15 | 0.008 | |

| Combination | −1.50 | 2.02 | 0.46 | |

| Escitalopram (reference) | – | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| Week × Treatment | 0.13 | |||

|

| ||||

| Week × bupropion | −0.37 | 0.21 | 0.08 | |

| Week × combination | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.93 | |

| Week × escitalopram (reference) | – | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| HAMD17 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.0002 | 0.008 |

|

| ||||

| HAMD17 × Treatment | 0.0003 | |||

|

| ||||

| HAMD17 × bupropion | −0.35 | 0.09 | 0.0001 | |

| HAMD17 × combination | −0.09 | 0.09 | 0.32 | |

| HAMD17 × escitalopram (reference) | – | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| Week × HAMD17 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.07 |

|

| ||||

| Week × HAMD17 × Treatment | 0.02 | |||

|

| ||||

| Week × HAMD17 × bupropion | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| Week × HAMD17 × combination | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.006 | |

| Week × HAMD17 × escitalopram (reference) | – | – | – | |

Note. All analyses were adjusted for child age (centered) and gender, site, and within-family correlation, and were restricted to subjects with HAMD17 data.

Beta denotes regression coefficient corresponding to specific effect.

There was a statistically significant interaction between change in maternal depression symptoms over time and treatment (i.e., the week × HAMD-17 × treatment interaction in Table 2b), implying that the association between maternal depressive symptoms and child depressive symptoms over time varied significantly by maternal treatment assignment (p=0.02).

To investigate these results further, we examined each treatment arm separately (Table 3). This investigation revealed that a reduction in mother’s HAMD-17 scores was associated with a reduction in the child’s CDI scores over time, as originally hypothesized, but only in mothers treated with escitalopram. That is, there was a positive association between HAMD-17 scores and child CDI scores (Beta=0.11, SE=0.05, p=0.03), and the coefficient corresponding to week (number of weeks from baseline) decreased in magnitude and statistical significance with the addition of HAMD-17 scores as the time-dependent covariate (i.e., the beta coefficient decreased in absolute magnitude from 0.40 [SE=0.06, p<0.001] to 0.27 [SE=0.08, p=0.002]). Furthermore, when the effects of HAMD-17 scores on child CDI scores were allowed to vary over time (by inclusion of an additional HAMD-17 × week interaction term) this effect was found to be highly significant (p=.001). These results suggest that as maternal HAMD-17 scores decrease over time there is a corresponding decrease in child depressive symptoms (CDI scores) but the strength of the association decreases over the first eight weeks of the study until it levels off during the last four weeks. The effect of HAMD-17 scores did not vary with time for CDI scores of children whose mothers were on bupropion (i.e., the week × HAMD-17 × treatment interactions are non-significant). Furthermore, there was a negative association between mother’s HAMD-17 scores and child’s CDI scores on average, and the magnitude of the slope coefficient increased rather than decreased with the addition of mothers’ HAMD-17 scores as time-dependent covariates, suggesting that a decrease in mother’s HAMD-17 scores does not explain the decrease in child’s CDI scores for mothers on bupropion. There was no significant change over time in CDI scores for children whose mothers were on combination treatment, therefore the question of mediation of change in child CDI scores over time by change in mothers’ depressive symptoms over time became irrelevant for this group.

Table 3.

Mother’s Depressive Symptom Score (HAMD-17) and Children’s Depressive Inventory Score (CDI) by Maternal Treatment

| Predictors | HAMD17 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Unadjusted Model | Add Main Effect | Add Interaction | |||||||

| Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | |

| Combination treatmenta | |||||||||

| Week | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.43 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| HAMD17 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| HAMD17 × Week | – | – | – | ||||||

| Bupropion | |||||||||

| Week | −0.19 | 0.08 | 0.03 | −0.31 | 0.10 | 0.004 | −0.28 | 0.18 | 0.12 |

| HAMD17 | −0.12 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.10 | |||

| HAMD17 × Week | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.88 | ||||||

| Escitalopram | |||||||||

| Week | −0.40 | 0.06 | <0.0001 | −0.27 | 0.08 | 0.002 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.65 |

| HAMD17 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.0005 | |||

| HAMD17 × Week | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.003 | ||||||

Note. All analyses were adjusted for child age (centered) and gender, site, and within-family correlation, and were restricted to subjects with HAMD17 data.

Additional analysis was not performed for children of mothers in combination treatment because CDI score did not change significantly over time in the unadjusted model.

Similar analyses to determine whether reduction in maternal depressive scores explained the differential treatment effects on child impairment (CIS scores) found no significant relationship between improvement in child CIS scores and reduction in mother’s HAMD-17 scores for any of the three treatments.

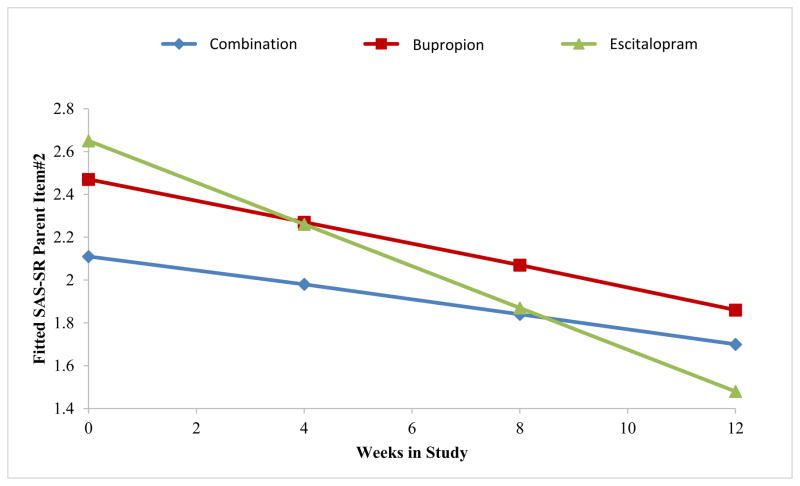

Possible Reasons for Mother’s Treatment Effect on Children

The next exploratory analyses were carried out to understand the effect of mother’s treatment on the decrease in children’s depressive symptoms. Results of fitting a regression model to overall maternal social functioning (SAS-SR) scores showed a significant linear decrease in overall scores over time (Beta1=−0.05, SE=0.01, t=−5.84, p<0.001), but the rate of improvement did not vary significantly with treatment. However, when we fit the same model to the parenting role scores over time, we found a marginally significant differential treatment effect over time (p=0.09) (see eFigure 3), with mothers on escitalopram showing greater improvement in parental functioning over the study period as compared to those treated with bupropion or combination. This effect was primarily due to a differential effect of escitalopram as compared to the other medications (p=0.02) of the mother’s report “being able to talk to and listen to my child” (Figure 3). The results with parental role scores and the individual parenting items are shown in eTable 4.

Figure 3. Estimated Trends in SAS-SR Parenting Item “Been able to talk to and listen to your child” Over 12 Weeks.

Note. Figure shows means for 27 combination-treated mothers, 20 bupropion-treated mothers, and 29 escitalopram-treated mothers. Lower scores indicate improvement. All analyses were adjusted for site. Time trends by treatment imply that mothers on escitalopram improved the most (Beta=−0.10, SE=0.02, t=−5.83, p= <0.0001), followed by mothers on bupropion (Beta=−0.05, SE=0.02, t=−2.94, p=0.004) and combination treatment (Beta=−0.03, SE=0.01, t=−2.35, p=0.02). The overall week × treatment interaction was statistically significant (F=4.12, df=2,150, p=0.02), implying that change in scores on SAS-SR parent item #2 over time is significantly different between treatment groups. Pairwise comparisons showed significant differences between mothers on combination vs. escitalopram treatment (Beta=0.06, SE=0.02, t=2.82, p=0.005), marginally significant differences between mothers on bupropion vs. escitalopram (Beta=0.05, SE=0.02, t=1.92, p=0.057), and no significant differences between mothers on combination vs. bupropion treatment (Beta=0.02, SE=0.02, t=0.73, p=0.47).

We next examined the child’s report of mother’s care and affection on the Parental Bonding Inventory (PBI). Results showed that over time, children of escitalopram mothers reported a significant increase in maternal care and affection (Beta=0.17, SE=0.08, t=2.00, p=0.047), while those of both combination (Beta=−0.09, SE=0.09, t=−1.04, p=0.30) and bupropion (Beta=−0.09, SE=0.09, t=−0.95, p=0.34) reported no significant change in maternal care and affection over time. The overall week × treatment interaction (F=2.99, df=2,164, p=0.05) suggested that changes in child-reported maternal care and affection over time differed between treatment groups. This was confirmed in pairwise comparisons, with significant differences observed between children of mothers on combination treatment vs escitalopram (Beta=−0.26, SE=0.12, t=−2.14, p=0.03) and on bupropion vs escitalopram (Beta=−0.26, SE=0.13, t=−2.04, p=0.04), while there were no significant differences between children of mothers on combination treatment vs bupropion (Beta=−0.001, SE=0.13, t=−0.01, p>0.99) (eTable 5).

There were no significant differential medication side effects or dosing patterns in mothers. The mean daily doses were escitalopram = 23.8 mg, bupropion = 244.8 mg, and combination (escitalopram = 24.3 mg, bupropion = 314.3 mg).

There was no significant difference in the percent of children at baseline or in the past who received psychiatric treatment by maternal treatment. During the 12 weeks, there were significant differences: 31.5%, 20.6%, and 8.7% of children whose mothers were receiving combination, bupropion, and escitalopram, respectively (p<0.02), were receiving psychiatric treatment. These findings suggest that children’s greater improvement in the mothers receiving escitalopram could not be explained by children having received treatment. The children of mothers on escitalopram received the least amount of treatment.

Gerra et al. (in press), in a re-analysis of the Adult Study, examined negative affectivity ()— which included three domains of aversive moods: guilt, hostility/irritability, and fear/anxiety—as a moderator of differential treatment response. This was based on Nutt et al. and Stahl23,24 who suggested that high negative affectivity is a result of serotonin deficiency and should respond to antidepressants that enhance serotonin neurotransmission, namely escitalopram vs. bupropion. This finding was confirmed in the full adult sample and we tested it in relationship to the mothers and children. We found that children of mothers with low negative affectivity showed a significant decrease in depressive symptoms (CDI scores) over time regardless of mothers’ treatment assignment (eFigure 4). For children of mothers with high negative affectivity, only children whose mothers were on escitalopram showed a decrease in CDI scores (eFigure 5).

Further investigation showed that for children of mothers with high baseline negative affectivity, the overall week × treatment interaction was significant (F=4.84, df=2,113, p<0.01), implying that CDI changes over time differ between treatment groups. Individual betas showed that only children of mothers treated with escitalopram (Beta=−0.33, SE=0.09, p=0.001) showed a significant reduction in CDI scores over time, whereas children of mothers with high negative affectivity at baseline, treated with combination (Beta=0.03, SE=0.09, p=0.77) and bupropion (Beta= 0.02, SE=0.10, p=0.85) showed no significant changes over time in CDI scores. However, a formal test of a three-way interaction of differential effects of maternal treatment on children’s CDI scores by maternal baseline negative affectivity did not reach statistical significance, possibly because of lack of statistical power.

DISCUSSION

Depressed mothers receiving escitalopram, bupropion, or combination treatment had a high remission rate (67%), a significant reduction in symptoms over 12 weeks, and no statistically significant treatment differences. Our main hypothesis that mothers on combination treatment would have an earlier onset and higher rate of remission than either of the monotherapies and that the outcome in their children would follow was not confirmed and could not explain the findings in children. However, there were significant treatment effects in their children. Children whose mothers were on escitalopram showed significantly greater improvement on symptoms and functioning as compared to children whose mothers were on the other treatments. Furthermore, improvement in mothers’ depressive symptoms was significantly related to improvements in children’s depressive symptoms over the 12 weeks only in children whose mothers were on escitalopram.

We then undertook a number of exploratory analyses to understand the findings. Mothers on escitalopram and not on the other medications showed improvement in self-reported parental functioning. They reported being better able to talk to and listen to their children. These findings were paralleled in the children’s reports that their mothers on escitalopram as compared to the other two medications were more caring over the 12 weeks. These differential treatment effects could not be explained by differential dose of maternal medications or side effects, or by the child’s receiving psychiatric treatment. However, mothers with high negative affectivity at baseline moderated the effects of escitalopram.

We do not know why children did better when their mothers were on escitalopram as compared to bupropion or combination treatment, or why the results on escitalopram were not similar to combination treatment. There is a small advantage (6%) of SSRIs as compared to bupropion in the treatment of anxious depression.35,36 Negative affectivity, which captures high levels of stress, irritability, and anxiety, may be similar to DSM-5 major depression with anxious distress. This subgroup may be better treated with a medication like escitalopram that enhances serotonergic neurotransmission as compared to bupropion, which enhances dopaminergic neurotransmission. The combination treatment group results might suggest that avoiding bupropion’s effects is important. These findings do not imply that treating depressed mothers with escitalopram is better for their children than other SSRIs or psychotherapy.12

The effects of improved parenting on children are comparable to Garber et al.,11 who showed that the relationship between parent’s and child’s depressive symptoms was partially mediated by improvement in parental acceptance and care. Both studies suggested that reduction in maternal symptoms resulted in changes in parenting behavior, which in turn may be related to symptom reductions in their children. Our findings are similar to the Swartz et al. study,12 which found that the decrease in the children’s depressive symptoms (CDI) but not impairment (CIS) was mediated by improvement in the mothers’ depressive symptoms.

The study has limitations. Our treatment of mothers was limited to three medications, no psychotherapy, no placebo, and no longitudinal control sample of children of non-depressed mothers.11 We did not include fathers. While controlled clinical trials are needed to determine the effects of maternal treatment, differential treatment drop-out could confound analyses in a randomized study. Our low attrition of mothers and children is a strength. The sample size, while the largest of this type of study, was still too small to fully carry out the exploratory analyses. In addition, multiple ancillary analyses were performed without statistical adjustments for multiplicity, and consequently results from these exploratory analyses must be interpreted with caution. There were fewer married mothers in the bupropion group, but marital status and living arrangement were controlled in all analyses and were explained by site differences (fewer married women in NY as compared to Ottawa). The differential effect of mothers’ receiving escitalopram on child outcomes was found in both sites. The Parental Bonding Inventory (PBI), while used in young children, may be less reliable in 7- and 8-year-olds. Also, the negative affectivity measurement is based on unproven approximations and requires replication. Finally, the maximum medication dose of escitalopram is higher than the 20 mg per day currently recommended by the FDA. The average maternal dose over 12 weeks was about 24 mg, and the average maximum dose at last interview was 30 mg. However, dose was not related to outcome in the mothers or in their children.

Clinically, medication for depression may not show differential effects on standard symptom measures used in clinical trials. More subtle behavioral effects may be captured by measures of parental functioning which could show differential effects on children. A similar conclusion regarding behavioral outcome was reached by an NIMH panel examining the STAR*D data.37 Personalizing the treatment of depressed mothers may be enhanced by assessing parental behavior and monitoring the impact on children. Concomitant targeted interventions that enhance parenting may be useful. Medications which reduce symptoms of high anxious distress and irritability may be required. These findings also highlight the importance of active treatment of depressed mothers which may help them and their children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants MH082255 (Parental Remission for Depression and Child Psychopathology; MMW, PI), MH076961-01A2 (JWS, PI), and MH077285-01A2 (PB, PI). The authors thank Dr. Marc Gameroff for his computational support.

Footnotes

Clinical trial registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov #NCT00519428

References

- 1.Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR, O’Connor EE. Transmission and prevention of mood disorders among children of affectively ill parents: a review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:1098–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batten LA, Hernandez M, Pilowsky DJ, Stewart JW, Blier P, Flament MF, Poh E, Wickramaratne P, Weissman MM. Children of treatment-seeking depressed mothers: A comparison with the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) Child Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:1185–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammen C, Burge D, Burney E, Adrian C. Longitudinal study of diagnoses in children of women with unipolar and bipolar affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:1112–1117. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810240032006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Rush AJ, Hughes CW, Garber J, Malloy E, King CA, Cerda G, Sood AB, Alpert JE, Wisniewski SR, Trivedi MH, Talati A, Carlson MM, Liu HH, Fava M, Weissman MM. Children of currently depressed mothers: a STAR*D ancillary study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:126–136. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weissman MM, Feder A, Pilowsky DJ, Olfson M, Fuentes M, Blanco C, Lantigua R, Gameroff MJ, Shea S. Depressed mothers coming to primary care: maternal reports of problems with their children. J Affect Disord. 2004;78:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Verdeli H, Pilowsky DJ, Grillon C, Bruder G. Families at high and low risk for depression: a 3-generation study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:29–36. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker ED, Copeland W, Maughan B, Jaffee SR, Uher R. Relative impact of maternal depression and associated risk factors on offspring psychopathology. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:124–129. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Talati A, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Hughes CW, Garber J, Malloy E, King CA, Cerda G, Sood AB, Alpert JE, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ. Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: a STAR*D-child report. JAMA. 2006;295:1389–1398. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne P, Talati A, Tang M, Hughes CW, Garber J, Malloy E, King C, Cerda G, Sood AB, Alpert JE, Trivedi MH. Children of depressed mothers 1 year after the initiation of maternal treatment: findings from the STAR*D-Child Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1136–1147. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wickramaratne P, Gameroff MJ, Pilowsky DJ, Hughes CW, Garber J, Malloy E, King C, Cerda G, Sood AB, Alpert JE, Trivedi MH, Fava M. Children of depressed mothers 1 year after remission of maternal depression: findings from the STAR*D-Child study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;42:962–971. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garber J, Ciesla JA, McCauley E, Diamond G, Schloredt KA. Remission of depression in parents: links to healthy functioning in their children. Child Dev. 2011;82:226–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swartz HA, Frank E, Zuckoff A, Cyranowski JM, Houck PR, Cheng Y, Fleming MAD, Grote NK, Brent DA, Shear MK. Brief interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed mothers whose children are receiving psychiatric treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1155–1162. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coiro MJ, Riley A, Broitman M, Miranda J. Effects on children of treating their mothers’ depression: results of a 12-month follow-up. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:357–363. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verduyn C, Barrowclough C, Roberts J, Tarrier N, Harrington R. Maternal depression and child behaviour problems: randomised placebo-controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural group intervention. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:342–348. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Tessier P, Deliyannides D, Hellerstein D, Norris S, Amat J, Pilowski DJ, Blondeau C, O’Shea D, Chen Y, Bergeron R, Withers A, Blier P. Combination antidepressant therapy for major depressive disorder: speed and probability of remission. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;52:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.First MB, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-1) In: Rush AJ, First MB, Blacker D, editors. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2008. pp. 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endicott J, Cohen J, Nee J, Fleiss J, Sarantakos S. Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Extracted from Regular and Change Versions of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:98–103. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780260100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, Markowitz JC, Ninan PT, Kornstein S, Manber R, Thase ME, Kocsis JH, Keller MB. The 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, Thompson WD, Harding PS, Myers JK. Social adjustment by self-report in a community sample and in psychiatric outpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1978;166:317–326. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197805000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gameroff MJ, Wickramaratne P, Weissman MM. Testing the Short and Screener versions of the Social Adjustment Scale –Self-report (SAS-SR) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:52–65. doi: 10.1002/mpr.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nutt D, Demyttenaere K, Janka Z, Aarre T, Bourin M, Canonico PL, Carrasco JL, Stahl S. The other face of depression, reduced positive affect: the role of catecholamines in causation and cure. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21:461–471. doi: 10.1177/0269881106069938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stahl SM, Pradko JF, Haight BR, Modell JG, Rockett CB, Learned-Coughlin S. A review of the neuropharmacology of bupropion, a dual norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor. Prim Care Companion. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6:159–166. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v06n0403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerra ML, Marchesi C, AMat JA, Blier P, Hellerstein D, Stewart JW. Does negative affectivity predict differential responsivity to SSRI vs. non-SSRI? J Psychiatr Res. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09025. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory Manual. Toronto, ON, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brotman LM, Kamboukos D, Theise R. Symptom-specific measures for disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood or adolescence. In: Rush AJ, First MB, Blacker D, editors. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. 2. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2008. pp. 333–335. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bird HR, Shaffer D, Fisher P, Gould MS. The Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS): pilot findings on a measure of global impairment for children and adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1993;3:167–176. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker G, Tupling H, Brown LB. A parental bonding instrument. Br J Med Psychol. 1979;52:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singer JD. Using SAS PROC Mixed to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models and individual growth models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1998;29:323–355. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss RE. Modeling Longitudinal Data. New York, NY: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. Vol. 998. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papakostas GI, Stahl SM, Krishen A, Seifert CA, Tucker VL, Goodale EP, Fava M. Efficacy of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of major depressive disorder with high levels of anxiety (anxious depression): a pooled analysis of 10 studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1287–1292. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papakostas GI, Trivedi MH, Alpert JE, Seifert CA, Krishen A, Goodale EP, Tucker VL. Efficacy of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of anxiety symptoms in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 10 double-blind randomized clinical trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen RM, Greenberg JM, IsHak WW. Incorporating multidimensional patient-reported outcomes of symptom severity, functioning, and quality of life in the individual burden of illness index for depression to measure treatment impact and recovery in MDD. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:343–350. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.