Abstract

This study tested the hypothesis that frequent participation in cognitively-stimulating activities, specifically those related to playing games and puzzles, is beneficial to brain health and cognition among middle-aged adults at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Three hundred twenty-nine cognitively normal, middle-aged adults (age range, 43.2–73.8 years) enrolled in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention (WRAP) participated in this study. They reported their current engagement in cognitive activities using a modified version of the Cognitive Activity Scale (CAS), underwent a structural MRI scan, and completed a comprehensive cognitive battery. FreeSurfer was used to derive gray matter (GM) volumes from AD-related regions of interest (ROIs), and composite measures of episodic memory and executive function were obtained from the cognitive tests. Covariate-adjusted least squares analyses were used to examine the association between the Games item on the CAS (CAS-Games) and both GM volumes and cognitive composites. Higher scores on CAS-Games were associated with greater GM volumes in several ROIs including the hippocampus, posterior cingulate, anterior cingulate, and middle frontal gyrus. Similarly, CAS-Games scores were positively associated with scores on the Immediate Memory, Verbal Learning & Memory, and Speed & Flexibility domains. These findings were not modified by known risk factors for AD. In addition, the Total score on the CAS was not as sensitive as CAS-Games to the examined brain and cognitive measures. For some individuals, participation in cognitive activities pertinent to game playing may help prevent AD by preserving brain structures and cognitive functions vulnerable to AD pathophysiology.

Keywords: Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive activity, brain imaging, cognition, AD prevention

1. Background

Neural atrophy in areas such as the medial temporal lobe and temporoparietal association cortices are pathologic hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), even in its earliest stages (Chetelat & Baron 2003; Chiang et al. 2011; Dickerson et al. 2011). For example, cognitively normal individuals with atrophy in temporoparietal brain structures are at greater risk of progressing to clinical AD than those without such atrophy (Chiang et al. 2011; Dickerson et al. 2011). Impairment in episodic memory and executive function represents another well-established feature of AD (Storandt & Hill 1989); and there is growing recognition that, among cognitively normal adults, subtle changes in these cognitive domains may be present several years prior to the onset of dementia (Blacker et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2001). Given the public health epidemic that AD is becoming (Alzheimer's Association 2013), it is of paramount clinical and scientific interest to uncover factors that might forestall cognitive and brain alterations particularly in at-risk populations.

Participation in cognitively-stimulating activities has emerged as a potential mechanism for favorably altering the AD pathophysiological cascade among older adults (Crowe, Andel, Pedersen, Johansson, & Gatz 2003; Landau et al. 2012; Valenzuela, Sachdev, Wen, Chen, & Brodaty 2008; Wilson et al. 2002). For example, Valenzuela and colleagues (2008) found that older adults who reported high levels of lifespan mental activity exhibited significantly reduced rates of hippocampal atrophy over a 3-year period. With respect to cognition, Wilson et al. (2010) reported that, over 6 years of follow up, the annual rate of cognitive decline in cognitively normal older adults was reduced by 52% for each additional point on a cognitive activity measure. Similarly, another study (Hall et al. 2009) found increased engagement in cognitive activity at baseline decelerated memory decline by 0.18 years, independent of education. In a recent paper from our group (Jonaitis et al. 2013), participation in cognitively-engaging activities, especially those involving games such as puzzles and cards, was associated with better performance on cognitive tests even with adjustments for education and occupational complexity.

The majority of these investigations of the effects of cognitive activities on brain and neuropsychological indices has been conducted using older adult cohorts, and has primarily focused on how engagement in cognitive activities earlier in life affects these AD-relevant outcomes later in life. Therefore, it is not fully known whether concurrent participation in cognitive activities has any impact on neural health and cognition in midlife, especially in a cohort at increased risk for AD. Accordingly, building on our recent publication (Jonaitis et al. 2013), we investigated the influence of engagement in cognitively-stimulating activities on brain structures and cognitive functions vulnerable to the AD pathological cascade. Based on available evidence, we hypothesized that individuals who report more frequent participation in cognitive activities—specifically those related to playing games—will not only display greater gray matter (GM) volumes but also exhibit higher cognitive scores. Importantly, we also examined whether these associations are modified by core AD risk factors such as age, apolipoprotein E ε4 (APOE4) genotype, and having a parental family history (FH) of AD.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

The Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention (WRAP; Sager, Hermann, & La Rue 2005) is a large cohort of about 1500 cognitively normal, middle-aged adults between the ages of 40 and 65 at study entry. Three hundred and twenty-nine participants were selected for the present analyses on the basis of having completed a Cognitive Activity Scale (CAS; see Cognitive Activity Measure section below) and a T1 MRI scan. The sample was enriched with persons who had FH of AD (73.6%) and were APOE4 positive (39.5%). Table 1 presents the participants’ pertinent background characteristics. All study procedures were approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board and each subject provided informed consent prior to participation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of WRAP study participants*

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Female, % | 69.0% |

| Age | 60.31 (6.25) |

| Years of education | 16.04 (2.33) |

| APOE4 positive, % | 39.5% |

| Family history positive, % | 73.6% |

| MMSE | 29.45 (.92) |

| Interval between CAS and brain scan, y | 1.33 (1.19) |

Values indicate mean score and standard deviation, unless otherwise indicated.

APOE4=the varepsilon 4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene; MMSE=Mini-Mental State Examination; CAS=Cognitive Activity Scale.

2.2. Cognitive activity measure

We examined current frequency of cognitive activity using a modified version of the Chicago Health and Aging Study’s Cognitive Activity Scale (CAS; Wilson et al. 2002). The original version of the CAS was composed of seven cognitive activities commonly performed by older adults such as watching television; listening to the radio; reading newspapers; reading magazines or journals; reading books; playing games like cards, checkers, crosswords, or other puzzles; and going to museums. We modified this original version by including the following three items with the goal of extending the measure’s utility for our younger and more-educated population: attending lectures or continuing education classes, attending concerts or plays, and leisure use of a personal computer (Jonaitis et al. 2013). Participants provided responses to the CAS using a 5-point scale ranging from “once a year or less” [1] to “every day or nearly every day” [5], with higher scores indicating more frequent engagement in the activity.

Our primary analyses in this paper focused on the Games item (called CAS-Games henceforth), which inquires about frequency of “playing games like cards, checkers, crosswords, or other puzzles.” This a priori decision was informed by the CAS-Games’ face validity as a leisure activity that promotes brain health and cognition (ASA-Metlife Foundation 2006; CDC and the Alzheimer’s Association 2007) and because, of all 10 CAS items, it is arguably the item that best captures the essence of cognitively-stimulating activities (Jonaitis et al. 2013; Pillai et al. 2011). As secondary analyses, we also interrogated the CAS-Total score, computed as the sum of all responses on the CAS.

2.3. Neuroimaging protocol

The MRI images were acquired in the axial plane on GE ×750 3.0T scanner with an eight-channel phased array head coil (General Electric, Waukesha, WI). 3D T1-weighted inversion recovery prepared SPGR scans were collected using the following parameters: TI/TE/TR=450ms/3.2/8.2ms, flip angle=12°, slice thickness=1mm no gap, FOV=256, matrix size=256×256. Scanning was done after a minimum 4-hour fast from food, tobacco, caffeine, and medications with vasomodulatory properties. Participants underwent their MRI scans within 1.33 ± 1.19 years of completing the CAS and neuropsychological assessment.

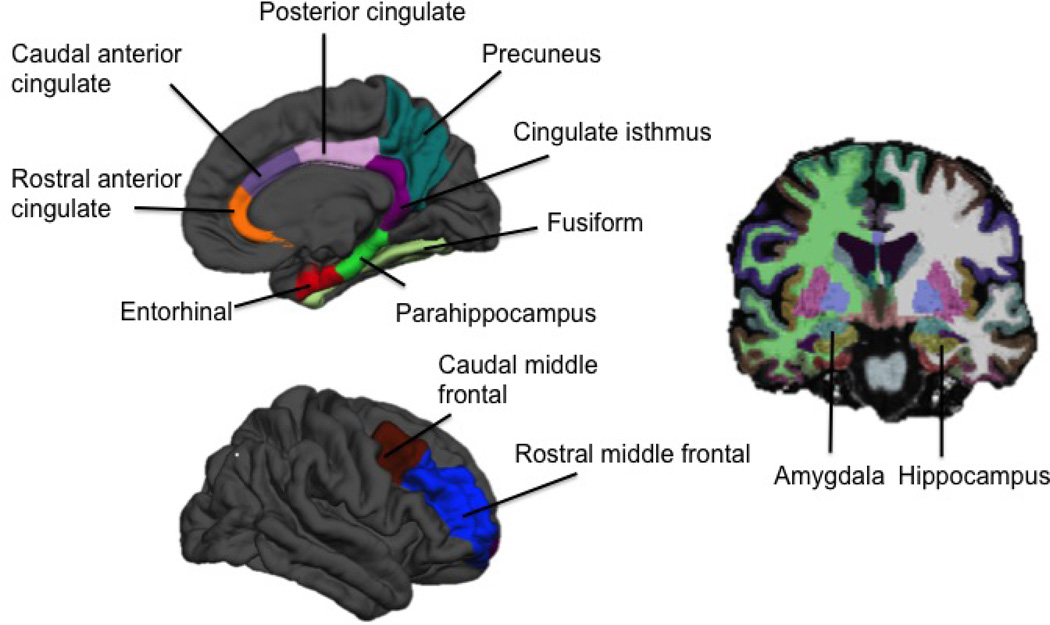

Gray matter volumes for the regions of interest (ROIs) examined in this study were derived using the FreeSurfer image analysis suite version 5.1.0 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). Technical details of this process have been described in prior publications (Dale, Fischl, & Sereno 1999; Fischl, Sereno, & Dale 1999). Each FreeSurfer output was visually inspected to ensure that the cortical reconstruction was accurate and without topological defects. For our analyses, we focused on ROIs implicated in episodic memory, executive function, or AD. These ROIs included the hippocampus, amygdala, entorhinal cortex, fusiform, parahippocampus, rostral and caudal anterior cingulate, rostral and caudal middle frontal gyrus, posterior cingulate, cingulate isthmus, and precuneus (see Figure 1). Hemispheric measurements were averaged to obtain a single bilateral value for each ROI.

Figure 1. Volumetric regions of interest examined in the study.

2.4. Neuropsychological assessment

The participants underwent an extensive battery of neuropsychological tests (Sager et al. 2005) that spanned conventional cognitive domains of memory, attention, executive function, language, and visuospatial ability. A previous factor analytic study (Koscik et al. 2014) of these tests within the larger WRAP cohort found that they map onto six cognitive factors i.e., Immediate Memory, Verbal Learning & Memory, Working Memory, Speed & Flexibility, Visuospatial Ability, and Verbal Ability. For this study, we only focused on the factors related to episodic memory and executive function. Constituent tests for the selected factors are as follows: Immediate Memory: Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) learning trials 1 and 2 (Schmidt 1996); Verbal Learning & Memory: RAVLT learning trials 3, 4, 5, and Delayed Recall (Schmidt 1996); Working Memory: Digit Span and Letter-Number Sequencing subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 3rd edition (Wechsler 1997); and Speed & Flexibility: Stroop Color-Word Test, Interference Trial (Trenerry, Crosson, DeBoe, & Leber 1989) and Trail-Making Test (Reitan 1958).

2.5. Data analysis

We assessed the relationship between CAS-Games and GM volume using a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with CAS-Games as our predictor and the volumetric ROIs as our outcome measures. We adopted a MANOVA approach to minimize alpha inflation given the number of ROIs [12] investigated. The model was adjusted for age, gender, time interval between CAS administration and MRI scan, and intracranial volume (ICV) because of their potential effects on brain structure. A significant omnibus MANOVA would provide justification for examining each ROI with follow-up univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs). For the association between CASGames and cognitive function, we fitted a series of linear regression models with CAS-Games as our predictor and the factor scores as our outcome measures. These analyses were adjusted for age and education because of their known influence on cognitive test scores.

Exploratory analyses were performed to determine whether any observed associations between CAS-Games and cognitive or regional GM volumes were moderated by major risk factors for AD, i.e., age, APOE4 status, and FH. This was accomplished by re-fitting the models described above while including a term for the interaction between the risk factor and CAS-Games. For example, FH*CAS-Games was added to the original models to determine whether FH moderates the association between CAS-Games and the examined outcome.

Another set of exploratory analyses were performed to determine whether CAS-Total would be as sensitive as CAS-Games to cognitive and volumetric alterations (Jonaitis et al. 2013). This was accomplished by substituting CAS-Total for CAS-Games in the original models described above. For all analyses conducted, evaluations of assumptions for ordinary least squares were carried out via graphical analyses as described by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007). All analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and only findings with a 2-tailed p-value ≤ .05 were considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Relationship between cognitive activity and brain structures

Pairwise plots revealed that the functional form of the association between CAS-Games and the regional GM volumes was not linear. Therefore, to optimize the derivation of the least squares estimates (Tabachnick & Fidell 2007), we fitted the MANOVA using a dichotomized version of the CAS-Games variable. Various dichotomizations were considered and we ultimately chose to split the sample into those who endorsed “everyday or about every day” (i.e. “5” on the original 5-point scale, “Frequent gamers”) versus those who did not (i.e., ≤4 on the original scale, “Infrequent gamers”), which theoretically constitutes an evaluation of CAS-Games’ maximal influence.

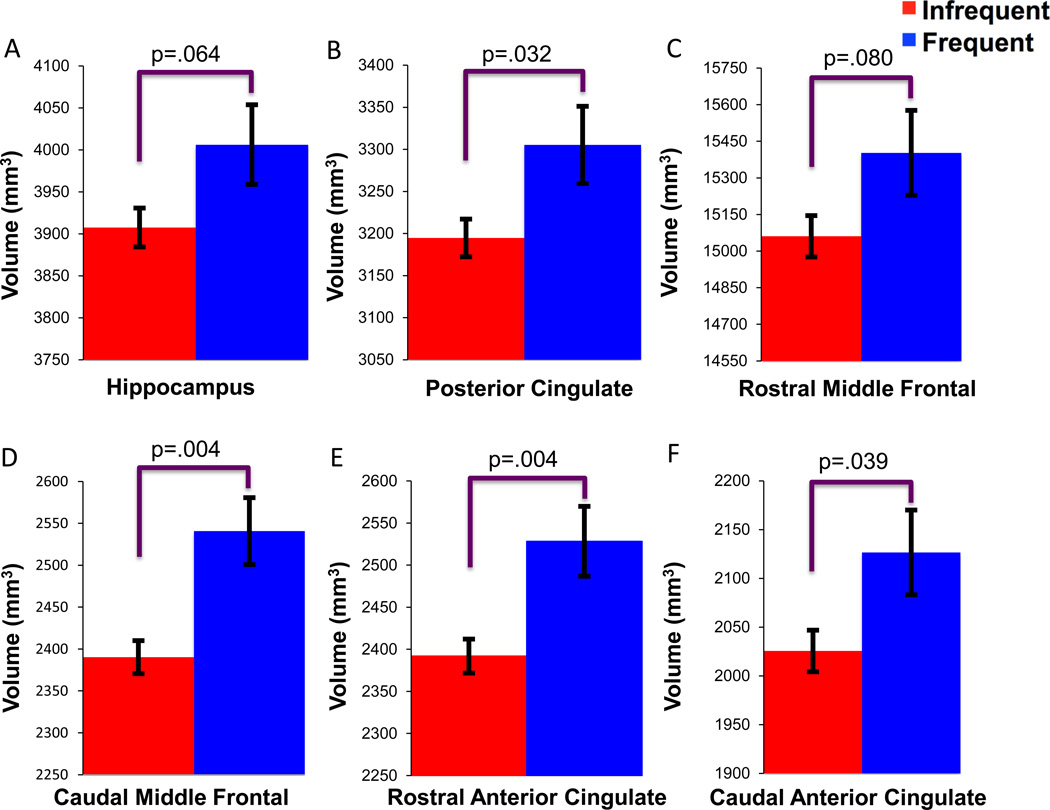

The MANOVA revealed a significant omnibus effect of CAS-Games on the regional GM volumes, Λ=.92, F(12, 313)=2.27, p=.009. Follow-up ANOVAs found significant CAS-Games effects for four ROIs. Mean (SE) and p values are as follows: rostral anterior cingulate (Infrequent gamers= 2391.95(20.28), Frequent gamers=2528.32(41.50), p=.004), caudal anterior cingulate (Infrequent gamers= 2025.57(21.27), Frequent gamers=2126.62(43.54), p=.039), caudal middle frontal gyrus (Infrequent gamers= 6156.41(55.08), Frequent gamers=6521.67(112.73), p=.004), and posterior cingulate (Infrequent gamers= 3194.69(22.42), Frequent gamers=3305.31(45.88), p=.032). There were nonsignificant trends for the hippocampus (Infrequent gamers= 3907.54(23.21), Frequent gamers=4006.25 (47.50), p=.064) and rostral middle frontal gyrus (Infrequent gamers= 15060.81(84.99), Frequent gamers=15402.53 (173.94), p=.080). These findings are displayed in Figure 2. The remaining ROIs were not significant (p’s> .185).

Figure 2. Relationship between CAS-Games and brain structure.

Blue bars=Frequent gamers (i.e.,“5” on the original 5-point CAS scale), Red bars=Infrequent gamers (i.e., ≤4 on the original CAS scale). A–F=adjusted mean volumes (mm3) and standard errors for the (A) hippocampus, (B) posterior cingulate, (C) rostral middle frontal, (D) caudal middle frontal, (E) rostral anterior cingulate, (F) caudal anterior cingulate. Sample size was 316 (62 Frequent gamers and 254 Infrequent gamers).

The exploratory MANOVA analyses performed to determine whether these effects were modified by core risk factors of AD failed to show a significant omnibus effect for any of the interaction terms: CAS-Games*age, Λ=.98, F(6, 318)=.87, p=.521; CAS-Games*APOE4, Λ=.97, F(6, 317)=1.87, p=.086, and CAS-Games*FH, Λ=.99, F(6, 317)=.50, p=.807.

3.2. Relationship between cognitive activity and cognitive performance

The regression models revealed significant associations between CAS-Games and Immediate Memory, Verbal Learning & Memory, and Speed & Flexibility, with a nonsignificant trend for Working Memory. The regression estimates all had positive weights, indicating that higher scores on CAS-Games were associated with better performance on these cognitive domains. These findings are depicted in Table 2. Of note, when gender was additionally included as a covariate in the models, the Immediate Memory and Verbal Learning & Memory findings were no longer statistically significant (p=.128 and p=.091, respectively). However, model diagnostics suggested that this might be due to collinearity between gender and other terms in the model as indicated by its Condition Index being 35.28 (cut point for absence of collinearity is < 15)(Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken 2003). Similar to the ROI analyses, exploratory analyses failed to find evidence that any of these effects were modified by age, APOE4, or FH (all interaction p’s > .169).

Table 2.

CAS-Games is associated with cognitive test scores

| Cognitive Factor |

β | Standard Error | t | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate Memory | .13 | .04 | 2.32 | .021 |

| Verbal Learning & Memory | .15 | .04 | 2.81 | .005 |

| Working Memory | .09 | .04 | 1.66 | .098 |

| Speed & Flexibility | .13 | .04 | 2.67 | .008 |

CAS-Games=Games item on the Cognitive Activity Scale. Analyses were adjusted for age and education.

Lastly, to investigate whether CAS-Games is truly capturing unique variance in cognition above and beyond the known association between brain volume and cognition, we re-ran the analyses that examined the associations between CAS-Games and cognition while additionally adjusting for brain volume. For this purpose, we created a composite brain volume measure by averaging the six ROIs shown to be associated with the CAS-games (i.e., hippocampus, posterior cingulate, rostral and caudal middle frontal, and rostral and caudal anterior cingulate). In these refitted models, CAS-Games continued to be significantly associated with Verbal Learning & Memory (p=.006), Immediate Memory (p=.022), and Speed & Flexibility (p=.007). Furthermore, when we reran the original models while adjusting for total GM volume, instead of the composite brain volume, measure, our original findings essentially persisted.

3.3. Relationship between total cognitive activity and cognitive and volumetric outcomes

The exploratory MANOVA examining the potential effect of CAS-Total on the ROIs was nonsignificant, Λ=.96, F(12, 313)=1.24, p=.258. The regression analyses performed to examine whether CAS-Total is associated with cognitive function revealed a significant effect only for Immediate Memory, β=.30, t= 2.18, p=.030. No other cognitive domains attained statistical significance (all p’s > .124).

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that engagement in cognitive activities pertinent to playing games was related to not only higher cognitive scores, but also greater GM volumes in areas vulnerable to AD pathology in a cohort of at-risk, middle-aged adults. These findings were not modified by known risk factors for AD, indicating that people at increased risk for AD (e.g., persons with FH of AD) may benefit from engagement in cognitively-stimulating activities just as much as their less vulnerable peers. We also found that CAS-Games was more strongly associated with our outcome measures than a composite measure of total cognitive activities (CAS-Total), suggesting that game playing might serve a unique role in the promotion of brain and cognitive health.

Currently, studies investigating the association between frequency of cognitive activity and AD-related brain changes have provided mixed results. For example, an epidemiological study (Valenzuela et al. 2008) analyzed lifespan cognitive activity of healthy older adults and found higher rates of cognitive activity were related to reductions in rate of hippocampal atrophy. Similarly, a recent study (Landau et al. 2012) found that older participants who frequently engaged in various cognitive activities had cerebral amyloid levels that were similar to young controls, while those who participated the least had amyloid levels in the range of AD patients. Data from animal studies (Cracchiolo et al. 2007) also provide evidence that cognitive activity is conducive to reduction in cognitive impairment and β-amyloid deposition, more so than physical and social activity. In contrast with the above studies, Vemuri and colleagues (2012) found no significant relationship between cognitive activity and hippocampal volume, amyloid accumulation, or glucose metabolism in a cohort of non-demented participants. Our results add to the current knowledgebase by showing that playing games and puzzles may influence a prognostic feature of AD—i.e., alterations in critical neuroanatomic structures—many years prior to possible disease onset, thus highlighting specific activities capable of doing so. Complete delineation of the mechanisms underlying these findings is beyond the scope of this study, but there is some indication that the mental stimulation provided by participation in cognitively-engaging activities may help promote neurogenesis to these specific brain regions (Mora 2013).

Past studies have also linked frequency of engagement in cognitive activity with cognitive function (Vemuri et al. 2012) and cognitive decline (Hall et al. 2009; Wilson et al. 2010). A recent cross-sectional study (Vemuri et al. 2012) has found that both current and lifetime cognitive activity of non-demented elderly adults were significantly correlated with a measure of global cognition, suggesting cognitive activity plays a role in the delay of dementia onset. Similar results were described in a study of community-dwelling elderly Chinese wherein those with higher levels of intellectual activity showed better cognitive function (Leung et al. 2010). Additionally, two longitudinal studies of non-demented older adults (Hall et al. 2009; Wilson et al. 2010) found that higher rates of mental activity are significantly associated with reduced rates of cognitive decline. Furthermore, a recent study (Pillai et al. 2011) found that the onset of accelerated memory decline was delayed by about two and a half years among dementia patients who performed crossword puzzles compared to those who did not. Our study complements these prior findings by showing that, in a cohort of late-middle-aged, at-risk adults, frequency of playing games is positively associated with performance on cognitive measures of Speed & Flexibility, Verbal Learning & Memory, and Immediate Memory. The memory findings were very intriguing because decrements in episodic memory are a hallmark feature of AD, even in its earliest stages (Blacker et al. 2007). Speed & Flexibility represents various executive functions that are essential for successfully navigating the demands of daily life, but also vulnerable to AD pathology (Reinvang, Grambaite, & Espeseth 2012). Overall, our findings suggest that frequent engagement in cognitive activities may hold potential as a buffer against cognitive deterioration in these cognitive abilities. Clinical trials that test the protective effect of cognitive stimulation will provide needed data on the extent to which games may play a role in delaying manifestation of frank dementia.

Our findings of an association between frequent game playing and greater brain volume and cognitive function are consistent with the reserve theory. Briefly, the reserve theory posits that inter-individual variations in the association between level of underlying AD brain lesion and degree of cognitive impairment may be due to an accumulation of cognitive or neural resources that allow individuals to sustain normal cognitive functioning despite deleterious brain insult (Stern 2012). However, it is important to note that while our finding of increased GM volume in Frequent gamers might be considered evidence that playing games promotes brain reserve, our results—strictly speaking—do not necessarily indicate that such activities promote cognitive reserve. To provide such evidence, we would need to show that, given the same degree of AD-related brain insults—such as may be seen on amyloid imaging—persons who engage in frequent game playing manifest fewer cognitive sequelae than those who do not. Ongoing analyses within our group are addressing this question. Even so, it is noteworthy that the brain regions that were associated with game playing in this study are some of the regions that have been shown in other studies (Alexander et al. 2012; Okonkwo et al. 2012) to be impacted in otherwise healthy, asymptomatic, middle-aged adults who either are at genetic risk for AD. This provides evidence that measurable gray matter differences are occurring decades prior to the potential onset of dementia, and highlight the importance of putative preventative approaches to mitigate such brain changes.

It was interesting that, in our study, CAS-Games was related to larger brain volume and cognitive health whereas CAS-Total (a composite measure of total cognitive activities) was not. This is somewhat at odds with findings from prior studies that have used such composite measures in their analyses and found significant relationships with several AD-relevant outcomes (Hall et al. 2009; Landau et al. 2012; Wilson et al. 2010; Wilson et al. 2002). Of note, Verghese et al. (2009) found that engaging in crossword puzzles—but not other cognitive activities—was associated with reduced risk of vascular cognitive impairment in the Bronx Aging Study. Our current finding regarding the relative sensitivity of CAS-Games vis-à-vis CAS-Total is also consistent with an earlier report from our group (Jonaitis et al. 2013), and might indicate that game playing has a unique role as a preventative strategy against AD and related disorders (ASA-Metlife Foundation 2006; CDC and the Alzheimer’s Association 2007; Pillai et al. 2011). It might also be a reflection of methodological issues related to “washout.” Specifically, because the CAS consists of diverse activities that may not all be tapping the same fundamental construct or equally conducive to brain/cognitive health, taking the sum of all responses might lead to a dilution of potent effects (e.g., game playing) by relatively weaker/unrelated ones (e.g., TV watching). Ongoing analysis within our group to determine the sensitivity and stability of each of the ten items that make up the CAS will help to further elucidate which activity or combination of activities may be the most impactful.

Our study has some limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the study precludes a conclusive arbitration of whether participating in games increases cognitive function and GM volumes or whether individuals who are endowed with these cognitive and neural resources—say, due to an enriched environment in childhood—elect to engage in more frequent participation in brain-healthy activities, such as game playing. Because the WRAP is an ongoing longitudinal study, we will be positioned to address this question as additional prospective data are collected. Such data will also enable us to determine the extent to which prior engagement in cognitively-stimulating activities is related to clinically-meaningful endpoints, such as the development of AD, in this risk-enriched cohort. Secondly, the demographic make-up of the cohort is not representative of the U.S. population. Therefore, the generalizability of our findings might be limited. Lastly, the CAS-Games is a single item that assesses diverse activities that potentially have differential cognitive demands (Carlson et al. 2012). It would be of interest to study in greater detail these distinct activities—e.g., crossword puzzles vs. board games—in order to determine their comparative effects on cognitive function and brain health.

In summary, this study found that participation in cognitive activities involving games and puzzles is related to better cognitive abilities and larger volumes in AD-vulnerable brain structures in a cohort of at-risk, middle-aged adults. Given the current lack of truly curative pharmaceutical agents for AD (Sperling, Jack, & Aisen 2011), these findings suggest that engagement in specific cognitive activities may promote healthy cognitive aging and, thereby, help prevent or delay AD for some individuals (Stern 2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Caitlin A. Cleary, BSc, Sandra Harding, MS, Jennifer Bond, BA, and the WRAP psychometrists for assistance with study data collection. In addition, we gratefully acknowledge the support of researchers and staff at the Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison, where the brain scans took place. Finally, we thank participants in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention for their continued dedication.

Funding:

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging grants K23 AG045957 (OCO), R01 AG027161 (MAS), R01 AG021155 (SCJ), P50 AG033514 (SA), and P50 AG033514-S1 (OCO); by a Veterans Administration Merit Review Grant I01CX000165 (SCJ); and by a Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1RR025011) to the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Portions of this research were supported by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, the Helen Bader Foundation, Northwestern Mutual Foundation, Extendicare Foundation, and from the Veterans Administration including facilities and resources at the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, WI.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Alexander GE, Bergfield KL, Chen K, Reiman EM, Hanson KD, Lin L, et al. Gray matter network associated with risk for Alzheimer's disease in young to middle-aged adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(12):2723–2732. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer's Association. 2013 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2013;9(2):208–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASA-Metlife Foundation. Attitudes and awareness of brain health poll. San Francisco, CA: American Society on Aging; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blacker D, Lee H, Muzikansky A, Martin EC, Tanzi R, McArdle JJ, et al. Neuropsychological measures in normal individuals that predict subsequent cognitive decline. Archives of Neurology. 2007;64(6):862–871. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.6.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MC, Parisi JM, Xia J, Xue QL, Rebok GW, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Lifestyle activities and memory: variety may be the spice of life. The women's health and aging study II. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2012;18(2):286–294. doi: 10.1017/S135561771100169X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC and the Alzheimer’s Association. The Healthy Brain Initiative: A national public health road map to maintaining cognitive health. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Ratcliff G, Belle SH, Cauley JA, DeKosky ST, Ganguli M. Patterns of cognitive decline in presymptomatic Alzheimer disease: a prospective community study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(9):853–858. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetelat G, Baron JC. Early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: contribution of structural neuroimaging. Neuroimage. 2003;18(2):525–541. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang GC, Insel PS, Tosun D, Schuff N, Truran-Sacrey D, Raptentsetsang S, et al. Identifying cognitively healthy elderly individuals with subsequent memory decline by using automated MR temporoparietal volumes. Radiology. 2011;259(3):844–851. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis fot the Behavioral Sciences. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cracchiolo JR, Mori T, Nazian SJ, Tan J, Potter H, Arendash GW. Enhanced cognitive activity--over and above social or physical activity--is required to protect Alzheimer's mice against cognitive impairment, reduce Abeta deposition, and increase synaptic immunoreactivity. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2007;88(3):277–294. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe M, Andel R, Pedersen NL, Johansson B, Gatz M. Does participation in leisure activities lead to reduced risk of Alzheimer's disease? A prospective study of Swedish twins. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58(5):P249–P255. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.5.p249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):179–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Stoub TR, Shah RC, Sperling RA, Killiany RJ, Albert MS, et al. Alzheimer-signature MRI biomarker predicts AD dementia in cognitively normal adults. Neurology. 2011;76(16):1395–1402. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182166e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis. II: Inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):195–207. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall CB, Lipton RB, Sliwinski M, Katz MJ, Derby CA, Verghese J. Cognitive activities delay onset of memory decline in persons who develop dementia. Neurology. 2009;73(5):356–361. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b04ae3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonaitis E, La Rue A, Mueller KD, Koscik RL, Hermann B, Sager MA. Cognitive activities and cognitive performance in middle-aged adults at risk for Alzheimer's disease. Psychology and Aging. 2013;28(4):1004–1014. doi: 10.1037/a0034838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koscik RL, La Rue A, Jonaitis E, Okonkwo OC, Johnson SC, Bendlin BB, et al. Emergence of mild cognitive impairment in late-middle-aged adults in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, in press. 2014 doi: 10.1159/000355682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau SM, Marks SM, Mormino EC, Rabinovici GD, Oh H, O'Neil JP, et al. Association of lifetime cognitive engagement and low beta-amyloid deposition. Archives of Neurology. 2012;69(5):623–629. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung GT, Fung AW, Tam CW, Lui VW, Chiu HF, Chan WM, et al. Examining the association between participation in late-life leisure activities and cognitive function in community-dwelling elderly Chinese in Hong Kong. International Psychogeriatrics. 2010;22(1):2–13. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209991025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora F. Successful brain aging: plasticity, environmental enrichment, and lifestyle. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2013;15(1):45–52. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.1/fmora. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonkwo OC, Xu G, Dowling NM, Bendlin BB, Larue A, Hermann BP, et al. Family history of Alzheimer disease predicts hippocampal atrophy in healthy middle-aged adults. Neurology. 2012;78(22):1769–1776. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182583047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai JA, Hall CB, Dickson DW, Buschke H, Lipton RB, Verghese J. Association of crossword puzzle participation with memory decline in persons who develop dementia. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2011;17(6):1006–1013. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinvang I, Grambaite R, Espeseth T. Executive Dysfunction in MCI: Subtype or Early Symptom. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:936272. doi: 10.1155/2012/936272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM. Validity of the trail making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Sager MA, Hermann B, La Rue A. Middle-aged children of persons with Alzheimer's disease: APOE genotypes and cognitive function in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18(4):245–249. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test: A Handbook. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Jack CR, Jr, Aisen PS. Testing the right target and right drug at the right stage. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(111):111cm133. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(11):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storandt M, Hill RD. Very mild senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. II. Psychometric test performance. Archives of Neurology. 1989;46(4):383–386. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520400037017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5 ed. New York: Harper Collins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Trenerry M, Crosson B, DeBoe J, Leber L. Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela MJ, Sachdev P, Wen W, Chen X, Brodaty H. Lifespan mental activity predicts diminished rate of hippocampal atrophy. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vemuri P, Lesnick TG, Przybelski SA, Knopman DS, Roberts RO, Lowe VJ, et al. Effect of lifestyle activities on Alzheimer disease biomarkers and cognition. Annals of Neurology. 2012;72(5):730–738. doi: 10.1002/ana.23665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese J, Cuiling W, Katz MJ, Sanders A, Lipton RB. Leisure activities and risk of vascular cognitive impairment in older adults. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2009;22(2):110–118. doi: 10.1177/0891988709332938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. WAIS-III: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - 3 rd edition. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Aggarwal NT, Boyle PA, Hebert LE, Mendes de Leon CF, et al. Cognitive activity and the cognitive morbidity of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2010;75(11):990–996. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f25b5e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Mendes De Leon CF, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Bienias JL, Evans DA, et al. Participation in cognitively stimulating activities and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2002;287(6):742–748. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.6.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]