The interactions of nanoparticles with biological systems at a cellular and molecular level is a rapidly evolving field that requires an improved understanding of endocytic trafficking as the principal driver and regulator of signaling events and cellular responses. An understanding of these processes is vital to many applications, including nanomedicine delivery, cellular imaging, and cytotoxicity analysis, among others. Studies investigating the complex interplay of these processes and their relationship to well-defined targeted nanoparticle probes exploiting endocytic pathways are notably lacking, particularly for particles at the sub-10 nanometer scale. It is known that integrins, as cell-adhesion molecules are trafficked through the endosomal pathway and participate in diverse roles controlling intercellular and cell-extracellular matrix interactions, such as signal transduction, cell migration, and proliferation. Here we report that ultrasmall, non-toxic fluorescent silica core-shell nanoparticles (Cornell or C dots), surface PEGylated and functionalized with cyclic cRGDY peptide ligands (cRGDY-PEG-C dots), activate integrin-signaling pathways that, in turn, promote enhancement of cellular functions. First, nanomolar concentrations of particles, about two orders of magnitude higher than those achieved in vivo in current clinical trials, were shown to bind to and internalize within two αvβ3 integrin-expressing cell types, M21 melanoma cells and Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs), predominantly through an integrin receptor-dependent endocytic route. Second, we present evidence that at these and higher concentrations, integrin-mediated activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and multiple downstream signaling pathways in M21 cells occurs, in turn, upregulating phosphorylated protein expression levels and promoting concentration-dependent cellular migration and proliferative activity. Targeting FAK catalytic activity with the FAK inhibitor, PF-228, led to decreased phosphorylation levels and cellular migration rates. The findings presented here may inform the subsequent design of more effective targeted nanomedicine delivery systems and provide insights into the endocytic regulation of signal transduction.

1. Introduction

Integrins are transmembrane heterodimers of α and β subunits, both of which comprise a cytoplasmic tail, membrane-spanning helix, and extracellular domain; these mediate a broad range of interactions between the intracellular actin-cytoskeleton and the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM).[1, 2] In addition to their well-established roles in mediating adhesion to the ECM, integrins are essential for cellular migration and invasion, as well as for regulating downstream signaling events controlling these and other key biological processes, such as cell survival, proliferation, and cytoskeletal organization, in both tumor and normal cells[2–4]. Integrin binding to ligands in the ECM induces integrin clustering which, in turn, leads to binding and activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) via phosphorylation of its tyrosine residue 397 (Y937)[5], as well as activation of multiple downstream signaling proteins, including RhoGTPases, and the Src, Akt, and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs).[1] The αv-integrin subfamily is involved in cell migration[6], cell growth, tumor invasion/metastasis[7], and angiogenesis.[8–10] Moreover, the promotion of tumor survival and disease progression in the malignant phenotypes of certain tumors, such as metastatic melanoma, is linked to the expression of one of its members, αvβ3 integrin.[11–13]

Phenotypic changes associated with such invasive cancers are partially mediated by dramatic alterations in integrin surface expression and distribution, as well as integrin affinity and avidity for ECM substrates.[3, 14] For instance, the invasive front of malignant melanoma cells and angiogenic blood vessels is known to strongly express integrin αvβ3[15], which is only weakly expressed on pre-neoplastic melanomas and quiescent blood vessels. Further, alterations in adhesion profiles, the result of an increased affinity of integrins for their ligands, can regulate the migratory phenotype of cells. In prior studies, modulation of αvβ3 affinity has been noted in a number of cell types[16], while selective blocking of high-affinity αvβ3 has led to a reduction in migratory capacity.[17] Thus, the alteration of integrin expression and affinity profiles may modulate adhesive properties and intracellular signaling events, in turn, leading to more invasive and migratory phenotypes.

As one of the main types of ECM receptors for cell adhesion[2], integrins traffic through the endosomal pathway via an endocytic-exocytotic transport or recycling system that is known to influence their function.[1, 18–21] Endocytic trafficking is considered a principal driver of cell signaling[22, 23], and is thought to play a critical role in cellular migration, among other physiological and biochemical processes, by (1) maintaining a spatially restricted and polarized distribution of integrins [24], (2) modulating key signaling events [25], and (3) altering the recycling of other cell surface receptors (i.e., EGFR[26]). Internalization of many integrin heterodimers, including αvβ3 integrins, can occur through clathrin-dependent (i.e., receptor-mediated)[27, 28] and/or clathrin-independent[19, 29] endocytic mechanisms.

Integrins can be targeted by specific arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD)-containing moieties to deliver a variety of payloads, including nanoparticles (liposomes, polymers) and small molecular drugs for tumor-directed anti-angiogenesis therapy.[30–33] However, data addressing internalization mechanisms associated with these and alternative classes of particle-based probes (i.e., inorganic platforms) binding to integrin αvβ3 are lacking, particularly at sub-10 nm particle sizes. Endocytosis is responsible for the internalization of particles from the extracellular environment and is a major pathway for nanomaterial transport to lysosomes in mammalian cells. A growing number of distinct internalization routes can be exploited for transport that vary with the nature of the cargo, cell type, and/or proteins mediating cell membrane invagination. Particles can enter via one or more routes at the same time.[22]

In this study, we investigated the targeting of FDA IND-approved ultrasmall (~7.0 nm diameter) fluorescent core-shell silica nanoparticles (Cornell or C dots), surface-modified with polyethylene glycol (PEG) and cRGD peptide ligands containing the sequence cyclo-(Arg-Gly-Asp-d-Tyr-Cys) (cRGDY-PEG-C dots), and in specific cases radio-labeled at the Tyr residues with 124I (124I-cRGDY-PEG-C dots), to two αvβ3 integrin-overexpressing cell types (i.e., M21, HUVEC cells) (Figure 1A), and their subsequent alteration of key intracellular biological processes– migration, proliferative activity, and cellular adhesion/spreading. We explored the dependence of receptor binding/uptake kinetics, endocytosis, and integrin-mediated signaling profiles on particle concentrations and incubation times, in the absence and presence of a small molecule inhibitor, PF-573228 (referred to hereafter as PF-228)[34], targeting FAK catalytic activity. This study extends the results of previous efforts that comprehensively characterized this non-toxic platform, and revealed a distinct combination of structural, optical, and biological properties in melanoma models.

Figure 1.

Competitive integrin receptor binding and temperature-dependent uptake using cRGDY-PEG-C dots and anti–ανβ3 antibody for 2 cell types. A. Schematic of cRGDY-PEG-C dots. B. Specific binding and uptake of cRGDY-PEG-C dots in M21 cells as a function of temperature (4°C, 25°C, 37°C) and concentration (25nM, 100nM) using anti–ανβ3 integrin receptor antibody and flow cytometry. Anti–ανβ3 integrin receptor antibody concentrations were 250 times (i.e., 250x) the particle concentration. C. Uptake of cRGDY-PEG-C dots in M21 cells, as against M21L cells lacking normal surface integrin expression by flow cytometry. D. Selective particle uptake in HUVECs using anti-ανβ3 integrin receptor antibody and flow cytometry. Each data point in B–D represents the mean ± SD of 3 replicates. E. cRGDY-PEG-C dot (1 μM, red) colocalization assay with endocytic (transferrin-Alexa-488, FITC-dextran, green) and lysosomal markers (LysoTracker Red) after 4h particle incubation using M21 cells. Colocalized vesicles appear in yellow; Hoechst counterstain (blue) was used to visualize the cell nucleus. Scale bar = 15 μm (i, iii, iv) and 6 μm (ii).

2. Results

2.1 Binding of cRGDY-PEG-C-dots to M21 cells and HUVECs

The binding of cRGDY-PEG-C dots to αvβ3 integrins, expressed on the surfaces of human melanoma cells (M21) and human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs), was evaluated as a function of particle concentration and incubation time. A progressive increase in the binding of cRGDY-PEG-C dots to M21 cells and HUVECs as a function of concentration was observed by flow cytometry (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 1A). Particle binding demonstrated saturation at cRGDY-PEG-C dot concentrations of about 100 nM for both cell lines, with mean % gated values of about 80% for M21 cells and 96% for HUVECs. Binding kinetics was additionally investigated as a function of particle incubation time for both cell types at fixed particle concentration (i.e., 100 nM cRGDY-PEG-C dots). Maximum binding was achieved by 2 hours post-incubation and remained relatively stable thereafter (Supplementary Figure 1B). No significant variations in αvβ3 integrin receptor expression levels were observed for these cell lines by flow cytometry, although distinct differences in their responses might be traced to variations in other integrin receptor expression levels and/or expression profiles.

2.2 Endocytosis and Intracellular Trafficking of cRGDY-PEG-C-dots

To assess whether intracellular internalization occurs following incubation of cRGDY-PEG-C-dots with M21 cells and HUVECs, we examined the temperature-dependent uptake of these particles at three temperatures (i.e., 4°, 25°C and 37°C) after a 4-hour particle exposure time. The results, summarized in Figure 1B and 1D indicate a progressive increase in the intracellular localization of cRGDY-PEG-C-dots at 37°C as compared with 25°C, and a significant jump by more than an order of magnitude relative to the behavior at 4°C, in both cell lines tested. Further, internalization of cRGDY-PEG-C-dots was significantly blocked in the presence of excess (x250) antibody to αvβ3 receptor in M21 cells and HUVECs (Figures 1A, C), suggesting that the primary mechanism of uptake was receptor-mediated endocytosis. In addition, uptake in αvβ3-negative M21L cells was roughly a factor of 4- to 8-fold lower than that seen with αvβ3-expressing cells at both 37°C and 25°C (Figure 1C), respectively.

To further characterize the intracellular trafficking pathways navigated by cRGDY-PEG-C dots, we performed colocalization assays in M21 cells using cRGDY-PEG-C dots and fluorescent biomarkers for endocytic vesicles. Using an inverted confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP2 AOBS) equipped with a HCX PL APO objective (63x 1.2NA Water DIC D), targeted particles (~1 μM, red, 4-hr incubation) were found to be internalized in two distinct pathways (Figure 1E). Using endocytic markers LysoTracker Red (100 nM, green) (iv) and transferrin-Alexa488 (iii), uptake into acidic endocytic structures was confirmed, suggesting receptor-mediated pathway activity and gradual acidification of vesicles. Figure 1E shows co-localization of the particle and acidic endocytic vesicles (yellow puncta). cRGDY-PEG-C dots were also shown to co-localize with an established macropinocytotic marker, FITC-dextran (70-kDa), suggesting that uptake into macropinosomes was a second pathway of internalization.. No particles were found to enter the nucleus. Time-lapse imaging confirmed that particles were delivered to the lysosomal compartment in M21 cells, noting co-localization with the lysosomal marker, Lamp1 (Supplementary Movie #1).

2.3 Competitive αvβ3 Integrin Receptor Binding and Molecular Specificity

Competitive binding assays showed blocking of receptor-mediated particle binding in M21 cells and HUVECs (Supplementary Figure 2A) by 80%–85% and 30–40%, respectively, using excess (x50–x100) cRGDY peptide and gamma counting of the radiolabeled particle tracer (124I-PEG-cRGDY-C dots). By contrast to cRGDY-PEG-C dots, significantly less receptor binding in M21 cells (~30%–43%) and HUVECs (~13%–27%) was observed after incubation with non-targeted particle probes (i.e., PEG-C dots) by flow cytometry (Supplementary Figure 2B).

2.4 Influence of cRGDY-PEG-C dots on Cell Viability and Proliferation

To demonstrate that cRGDY-PEG-C dots did not adversely affect cell survival and proliferation, G0/G1 phase–synchronized M21 cells and HUVECs were exposed to a range of particle concentrations (25 – 200 nM cRGDY-PEG-C dots; 15 min or 24 hr) and subsequent incubation times (0 – 93 hrs) in serum-supplemented media (2%, 10% FBS) at 37°C, and time-dependent changes in absorbance were measured using an optical plate reader (λ=440 nm). Relative to controls (i.e., serum-supplemented media), absorbance measurements were relatively constant over the range of particle concentrations tested, suggesting no significant loss of cell survival (Supplementary Figure 3A, 3B). Further, no time-dependent decreases in absorbance were found following multi-dose (n=5) addition of 100 nM cRGDY-PEG-C dots to M21 cells and HUVECs, suggesting no alteration in the proliferative properties of cells (Supplementary Figure 3C, 3D).

2.5 Activation of the FAK pathway by cRGDY-PEG-C-dots

Integrin binding to RGD-bearing molecules in the ECM induces integrin clustering, which, in turn, leads to autophosphorylation of the non-receptor tyrosine kinase FAK at tyrosine 397, a binding site for the Src family kinases. Autophosphorylation of FAK induces activation of multiple signaling cascades and downstream pathway intermediates, including the Mitogen Activated Protein Kinases (MAPK), also known as the Ras/Raf/MEK/Erk pathway, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathways (AKT, mTOR, S6K) (Figure 2A). Recruitment of Src kinase leads to phosphorylation of FAK at tyrosine 576/577 and tyrosine 925 in the carboxyl-terminal region.

Figure 2.

Expression levels of phosphorylated FAK, Src, MEK, Erk1/2, and Akt in M21 cells. A. Simplified schematic of how FAK/Src complex transduces signals from integrin cell surface receptors via activation of downstream signaling pathways (PI3K-Akt, Ras-MAPK) to elicit a range of biological responses (boxes indicate assayed protein intermediates). B. Western blots of phosphorylated and total protein expression levels of key pathway intermediates after exposure (2h, 37°C) of G0/G1 phase-synchronized M21 cells to 100 nM cRGDY-PEG-C-dots relative to cells in serum-deprived (0.2% FBS) media (i.e., control). After trypsinization of cells and re-suspension of the pellet in lysis buffer, proteins were resolved by 4–12% gradient SDS-PAGE and analyzed by anti-FAK 397, pFAK 576/577, p-Src, pMEK, pErk1/2, and pAkt antibodies. Antibodies against FAK, Src, MEK, Erk, and Akt were also used to detect the amount of total protein. C. Graphical summary of percent signal intensity changes in phosphorylated to total protein (Adobe Photoshop CS2; see Methods) for particle-exposed versus serum-deprived cells. GF, growth factors; EC, endothelial cell; ECM, extracellular matrix.

To determine whether αvβ3 integrin-binding cRGDY-PEG-C dots modulate the activity of these pathways, we treated serum-deprived (0.2% FCS) M21 cells with 100 nM of cRGDY-PEG-C-dots for 2 hrs at 37°C; serum-deprived cells treated with 0.2% FCS alone served as controls. Western blot analyses of lysates from particle-exposed cells revealed enhanced expression of pFAK-397 and pFAK-576/577, Src, pMEK, pErk, and AkT (Figure 2B), which suggested activation of downstream signaling pathways. These findings, depicted graphically as normalized intensity ratios, have been expressed relative to their respective total protein levels, and normalized to corresponding values measured under control conditions (Figure 2C). Incubation of cells with only PEGylated C dots did not augment phosphorylation levels of the proteins tested (data not shown). More detailed response assessments were performed, which yielded intensity ratios for M21 cells that were maximal at earlier particle exposure times (i.e., up to 2 hours; Supplementary Figure 4) and that progressively increased with particle concentration (Supplementary Figure 5).

We evaluated whether the observed activation of downstream signaling pathways was dependent on the phosphorylation of FAK at tyrosine 397 (Tyr397) by blocking this pathway with a small-molecule inhibitor, PF-228. This inhibitor interacts with FAK in the ATP-binding pocket and effectively blocks both the catalytic activity of FAK protein and subsequent FAK phosphorylation on Tyr397. Following addition of two concentrations (i.e., 250 nM, 500 nM) of PF-228 to serum-deprived M21 cells 1 hour prior to the addition of 100 nM cRGDY-PEG-C dots, Western blot analyses revealed inhibition of the phosphorylation of Src, MEK1/2, Erk1/2, and FAK on Tyr397 (Figure 3A), which are graphically displayed as intensity ratios relative to their respective total protein levels (Figure 3B) or to actin (Supplementary Figure 6). Resulting ratios were normalized to corresponding values measured under control conditions. Inhibition of MEK1/2 and Erk1/2 phosphorylation was observed only at the higher inhibitor concentration (Figures 3A, B).

Figure 3.

Signaling induction and inhibition studies in M21 cells using PF-573228 (PF-228), a FAK inhibitor. A. Western blots of phosphorylated and total protein expression levels using the foregoing process of Figure 2 with the addition of two concentrations (250 nM, 500 nM PF-228) to cells prior to particle exposure (0.5h, 37°C). B. Summary of percent intensity changes of phosphorylated to total protein expression levels in particle-exposed versus control cells with and without PF-228.

2.6 Effect of cRGDY-PEG-C dots on Cellular Migration

In the following using a cell migration assay we sought to determine whether cRGDY-PEG-C dots altered the migration of M21 cells and HUVECs. Using time-lapse imaging, an initial set of experiments measured time-dependent changes in M21 cell migration into the cell-free zone of a well plate after exposing cells to successively higher particle concentrations (0 nM – 400 nM; 37°C) over a 96-hour time period (Figure 4A, i–xx). Statistically significant increases in mean area closure (i.e., ~87% – 92%) were observed as a percentage of the baseline values (t=0); these were essentially constant over the range of particle concentrations used relative to non-particle-exposed cells (73%; p<0.05) (Figure 4A, B). No significant changes were seen at earlier time intervals (Figure 4B). Incubation of HUVECs (37°C, 20 hours) over a range of cRGDY–PEG-C dot concentrations (i.e., 100 – 400 nM) in the presence of 0.2% FCS showed a statistically significant increase in the mean area closure for a concentration of 400 nM (i.e., 34%) (Figures 5A, B), as compared to 19% (p<0.05) for non-particle exposed cells (controls). No appreciable change in migration was observed at the lower particle concentrations used (Figures 5A, B). Particle-exposed cells (Supplementary Movie 2) were seen to exhibit higher rates of migration as compared to controls (Supplementary Movie 3).

Figure 4.

Effect of cRGDY-PEG-C dots on M21 cellular migration using time-lapse imaging. A. Time-dependent changes in cell migration using ORIS™ collagen coated plates for a range of particle concentrations (0 – 400nM; 37°C) in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 0.2% FBS, as against supplemented media alone (controls). Images were captured at time t=0 (pre-migration) and at subsequent 24h intervals following stopper removal by a Zeiss Axiovert 200M inverted microscope (5x/.25NA objective) and a scan slide module (Metamorph® Microscopy Automation & Image Analysis Software) for a total of 96 hrs. B. Graphical plot of changes in the mean area of closure (%) as a function of particle concentration using ImageJ software. Mean area of closure represents the difference in the areas demarcated by the border of advancing cells (pixels) at arbitrary time points and after stopper removal (t=0), divided by the latter area. Quadruplicate samples were statistically tested for each group using a one-tailed t-test: *, p=.011; **, p=.049; ***, p=.036. Scale bars are 100 μm and 33 μm (for magnified images of x and xv only).

Figure 5.

Effect of cRGDY-PEG-C dots on the migration of HUVECs. A. Serial HUVEC migration was assayed using the same process as in Figure 4 over a 24-hr time interval. The displayed images and area of closure values indicated are representative of a single experiment. B. Mean areas of closure (%) were determined over this time interval for a range of particle concentrations (0 – 400 nM) using ImageJ software. Triplicate assays were performed for each concentration and time point. One-tailed t-test *, p<0.05. Scale bar in all images is 76 μm.

We further showed that increases in cell migration rates were attenuated by the addition of FAK inhibitor, PF-228. Initial phase-contrast images were acquired after incubating HUVEC cells with 400 nM particles over a 24-hour time interval (Figure 6A, i–viii), and mean area closure was determined and graphically displayed relative to serum alone (Figure 6B). Percentage change in mean areas of closure relative to controls, and before and after addition of an inhibitor, was seen to decrease from +34% to +3%. Statistically significant differences were found between values for particle-exposed cells without inhibitor (p<0.03) and particles treated with different inhibitor concentrations (250nM, 500nM; p<0.001) relative to serum-deprived controls; differences between the first two groups were also statistically significant (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of HUVEC migration using PF-228. A. Same process as in Figure 5, except cells were exposed to 250 nM and 500 nM PF-228 (0.5h, 37°C) prior to particle exposure or incubation in 0.2% FCS supplemented media. B. Mean area closure (%) for cells incubated under the foregoing conditions. C. Tabulated p values for each exposure condition using a one-tailed t-test. Quadruplicate samples were run for each inhibitor concentration. Scale bar in all images is 50 μm.

2.7 Effect of cRGDY-PEG-C dots on Cellular Adhesion and Spreading

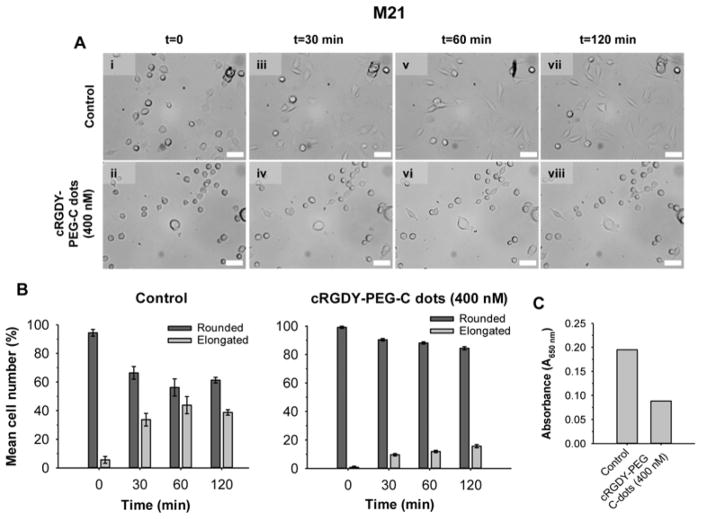

The RGD tripeptide is known to be a component of the extracellular matrix, which includes fibronectin and vitronectin. A competitive binding assay was performed using M21 cells pre-incubated without and with 400 nM cRGDY-PEG-C dots, after transferring cells to fibronectin-coated wells. About ~40–45% of the cells that were not pre-incubated with cRGDY-PEG-C-dots attached and spread on fibronectin-coated wells in the first 30 minutes. By contrast, a significantly lower percentage of M21 cells (i.e., ~10–15%) pre-incubated with 400 nM cRGDY-PEG-C-dots attached and spread on the fibronectin coated well, even 120 minutes after seeding (Figures 7A, 7B, Supplementary movies 4, 5). Average cell counts of ‘elongated’ (spreading cells) versus ‘rounded’ cells over a 2-hour period revealed that, in the absence of particles (i.e., control condition), cell spreading occurred, while a predominantly rounded appearance was seen in the case of particle-bound cells that were not able to attach to the substrate (Figure 7A). These results are graphically depicted in Figure 7B. Of note, cells pretreated with particles were seen to re-adhere to the substrate about 3 to 4 hours after particle exposure (data not shown). Quantification of the optical densities of cells after addition of methylene blue (absorbance) revealed that cells that attached and spread on fibronectin took up two times more methylene blue than particle-exposed cells (Figure 7D). We observed the same phenomenon if vitronectin-coated wells were used (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Modulation of M21 cell spreading and adhesion using cRGDY-PEG-C dots. A. Time-lapse imaging showing changes in cellular attachment and spreading. Cells were pre-incubated in 0.2% FBS-supplemented RPMI (0.5h, 25°C), without and with particles (400 nM), followed by seeding in (5 μg/ml) fibronectin-coated 96-well plates. Images were captured at t=0, 0.5h, 1h, and 2h using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M inverted microscope (20x/.4NA objective) and a scan slide module in Metamorph®. B. Graphical plot showing the mean number of rounded and elongated cells within two groups as a function of time: non-particle exposed (elongated, graph #1) and particle exposed (rounded, graph #2). Cells in each of three wells of a 96-well plate were manually counted in a minimum of three high power fields (x200 magnification) and averaged. C. Absorbance (λ=650 nm; SpectroMax M5 microplate reader) values for 4% paraformaldehyde fixed cells, exposed to media or 400 nM cRGDY-PEG C-dots, and treated with methylene blue reagent (1 ml; 1h, 37°C), as a measure of cellular attachment. Scale bar in A for all images is 30 μm. Quadruplicate samples were run for each group.

2.8 Influence of cRGDY-PEG-C dots on Cell Cycle in M21 Cells

Since integrin receptor activity can modulate cell survival and proliferation, we assessed the influence of cRGDY-PEG-C-dots on the cell cycle. G0/G1-phase-synchronized M21 cells were incubated for 48 hours using two concentrations of cRGDY-PEG-C-dots (100 nM, 300 nM) in 0.2% FCS supplemented media. Over this range, the percentage of cells in the S phase rose by 11%, with statistical significance achieved at 100 nM (p< 0.05) and 300 nM (p< 0.005) in relation to controls (Figure 8A, B). Corresponding declines of 6% and 5% were seen in the G1 and G2 phases of the cell cycle, respectively. These data suggest a trend toward an increased S phase population in the presence of cRGDY-PEG-C dots.

Figure 8.

Influence of cRGDY-PEG-C dots on cell cycle. A. Percentage (%) of viable cells in the G1, S, and G2 phases of the cell cycle as a function of particle concentration (0, 100, 300 nM) added to G0/G1-phase-synchronized M21 cells incubated for a total of 96 hours. Italicized numbers above each bar represent the percentage of cells (particle-incubated, control) in S, G1 and G2 phases, determined by flow cytometry. B. Representative cell cycle histograms are shown for cells under control conditions (i.e., no particles) and after incubation with 100 and 300 nM particles, respectively. One-way ANOVA: *, p<.05; **, p<.005 relative to S-phase control. Insets: Group mean values (n=3) ± SD for each cell cycle phase. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

3. Discussion

Integrins, as transmembrane receptors, serve as a bridge between cancer cells and enable direct binding between cancer cells with other important cellular as well as protein components of the ECM. As such, they play a key role in the bidirectional transmission of signals between the ECM and intracellular compartment. Integrin ligands are abundantly expressed by many cell types in the ECM of solid tumors[3], including vascular endothelial cells [35], while several ECM proteins (i.e., fibronectin, vitronectin) additionally share RGD, a common integrin-binding motif. Moreover, a number of tumor types, such as melanoma, express integrins directly.[13, 36] Integrin-mediated interactions with the ECM are known to activate a cascade of intracellular signaling events which play fundamental roles in a broad array of cancer cell activities, including cytoskeletal organization, migration, survival, proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis. The important role of integrins in the context of these cancer biological processes has made them appealing targets for oncologic therapy. However, the use of integrin antagonists, such as RGD-mimetic αvβ3/αvβ5 inhibitors (i.e., cilengitide, EM 121974, Merck), which treat cancer by targeting tumor cells directly and by inhibiting formation of a tumor vascular network, have generally not been efficacious in human cancer trials[37–40], noting the recent late-stage failure of cilengitide for treatment of newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients.[41] Given the more complex role of αvβ3 integrin in tumor angiogenesis [42, 43] and other important aspects of tumor biology, such as migration and intracellular signal transduction, identification of factors that reduce antitumor activity is crucial.[37]

Here we demonstrate that ~100 nM concentrations of αvβ3 integrin-binding cRGDY-PEG-C dots (or ~600 nM peptide concentrations; ~6 cRGD ligands per nanoparticle) modestly activated integrin-signaling events that controlled M21 and endothelial (HUVEC) cell migration rates and M21 proliferative activity. Of note, enhanced migration rates for both cell types were statistically significant relative to controls only at higher nanomolar particle concentrations (i.e., 400 nM) and after 96-hour exposure times in the case of M21 cells. By contrast, protein phosphorylation levels were not augmented under control conditions (i.e., 0.2% serum or PEGylated C dots). We inferred that the particle probe promoted these processes by increasing expression levels of key signaling pathway intermediates– pFAK-397, Src, pMEK, pErk, and AkT– to a modest degree in M21 cells (Figure 2). Additional lines of evidence supporting an integrin activation process were based upon inhibition of integrin-regulated FAK catalytic activity in particle-exposed cells in the presence of PF-228 and reduced phosphorylation of additional downstream targets (Src, MEK and Erk; Figure 3B) in a concentration-dependent manner. Decreased migration of particle-exposed HUVECs (Figure 6) was additionally observed in the presence of PF-228, a biological activity ascribed to FAK. This observation may be a consequence of decreased focal adhesion turnover[44], a process required for cell migration that involves the coordinated formation and disassembly of focal adhesions comprising areas of the cell surface interacting with the ECM. PF-228 was found to also inhibit cell migration in a concentration-dependent manner, consistent with a role for FAK kinase activity as a regulator of migration.[44] Importantly, biological assessments were not affected by changes in media conditions, as the latter did not alter particle sizes, concentrations, or brightness over a 24 hour period

Activation of FAK has been implicated in adhesion-dependent signaling events that regulate migration, as well as proliferation and survival.[45–47] Interestingly, however, PF-228 concentrations used to efficiently inhibit FAK activity and presumably regulate cell migration were not observed to alter cell growth nor induce apoptotic changes in this study, perhaps due to lack of sufficient inhibition of FAK kinase activity, growth conditions used, and/or pathway activation differences.[34] FAK activation is known to further mediate integrin-induced activation[48] of the RAS–MAPK (or RAS–Erk) pathway, leading to enhanced protein (i.e., MEK, Erk) expression levels that promote proliferative activity and survival.[49] Notably, we found that by blocking FAK catalytic activity, full activation of MEK and Erk was abrogated (Figure 3; Supplementary Figure 6).

Nearly all aspects of cellular signaling are tightly connected with endocytosis, leading to the notion that mechanistically diverse endocytic pathways may regulate intracellular signaling events during processes, such as cell migration.[19, 23, 29] For instance, receptor-mediated (i.e., clathrin dependent) endocytosis is thought to modulate signal transduction by controlling the surface density of signaling receptors, as well as the clearance and downregulation of activated signaling receptors.[29] Observations in biological systems have suggested that receptor internalization may be selectively driven by the physicochemical properties of nanoparticles. These properties will dictate specific endocytic route(s) of transport[22], in turn modulating downstream signaling and subsequent cellular biochemical and biomechanical responses.[50–52]

Although particle platforms may be surface-adapted with ligands (i.e., cRGD) to preferentially enhance receptor-mediated uptake via a particular pinocytic route, concomitant entry of particles via a number of endocytic routes will typically be found.[22] In this study, we demonstrated internalization of our αvβ3 integrin-targeting particle by two distinct pathways in M21 cells – receptor-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis; these pathways merged with the lysosomal compartment, as seen by Lamp-1 and time-lapse imaging (Figure 1E). Furthermore, two lines of evidence suggested that intracellular internalization occurred primarily via integrin-dependent receptor-mediated endocytosis. First, temperature-dependent particle uptake studies in M21 cells (Figure 1B) and HUVECs (Figure 1D) showed a dramatic decrease in the uptake of particles at 4°C (i.e., >95%) relative to that observed at 37°C.[53–55] Second, significant αvβ3 integrin receptor blocking of both cell lines (Figures 1B, 1D) was observed at all temperatures (4°C, 25°C, and 37°C) using an anti–ανβ3 integrin receptor antibody.

Endocytic trafficking pathways navigated by monomeric RGD ligands, multimeric RGD molecules, and anti-αvβ3 integrin monoclonal antibody (mAb 17E6) have also been studied in human melanoma (M21) cells.[56] In contrast to our findings for cRGDY-PEG-C dots, results point to an integrin-independent fluid-phase endocytic pathway for monomeric RGD. However, internalization of multimeric RGD molecules and blocking mAb via integrin-dependent endocytic pathways was similar to that seen for cRGDY-PEG-C dots. Of note, the use of multimeric RGD-complexes are known to increase integrin affinity and clustering[31, 57, 58], and thereby enhance integrin-mediated internalization. This was previously shown to be the case for our particle probe given its surface functionalization with multiple cRGD targeting ligands.[59] Furthermore, internalization and degradation of RGD-modified protein conjugates by αvβ3/αvβ5–expressing primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) have also been observed, a process inhibited by lysosomal degradation inhibitors, such as chloroquine.[60]

Cellular adhesion and spreading of M21 cells was assessed using a competitive binding assay. Initial pretreatment of M21 cells with particles (i.e., 400 nM) prior to their transfer to wells coated with RGD-containing substrates (i.e., fibronectin, vitronectin) suggested that cRGDY-PEG-C-dots had a greater binding affinity for αvβ3–expressing M21 cells than substrate-coated wells. Particle binding inhibited the ability of these cells to adhere and spread normally in culture, altering not only their cellular adhesion characteristics, but their physical (i.e., rounded morphology) and perhaps their biomechanical properties (i.e., elasticity). However, pretreated cells were found to retain their re-adhesion capacity; reattachment to the substrate was observed to occur within a ~2.5 hour time frame post-exposure. These findings were similar to those observed in a prior study[56] for melanoma cells pretreated with cRGD peptide. Under this condition, cells retained their re-adhesion capacity, as against those pretreated with mAb, which did not re-adhere to the substrate.

4. Conclusion

The results of this study provide a detailed biological assessment of a sub-10 nm, integrin-targeted fluorescent core-shell silica nanoparticle platform, cRGDY-PEG-C dots, in human melanoma and endothelial cell lines. By investigating cellular- and molecular-level interactions of this particle probe, interrelationships among endocytosis, a principal regulator of cellular function, and other critical physiological and biochemical processes, including signal transduction, migration, proliferation, and adhesion may be better understood. Although these processes are often investigated separately, they are not independent, and we therefore attempted to study several of these processes together in αvβ3 integrin-driven biological systems using cRGDY-PEG-C dots. This fluorescent inorganic nanoparticle platform is the first of its kind and class to be FDA-IND approved as a drug for clinical diagnostic applications. These particles primarily induced internalization via an integrin-dependent receptor-mediated endocytic process, likely the result of multivalency-enhanced binding given its surface functionalization with multiple cRGD targeting ligands. The data suggested that endocytosis and integrin trafficking at 100 – 400 nM particle concentration levels may have induced modest integrin-mediated activation of signaling protein intermediates, and promoted cell migration in HUVECs and M21 cells as well as M21 cell proliferative activity. Further in vitro investigations are still required to mechanistically explain how endocytic trafficking links integrins to cell migration and other cellular events in relation to particle-driven integrin-mediated signal transduction. It will be interesting to determine whether these results are generalizable across a range of integrin-expressing cells types, and the extent to which the number of surface-bound cRGD ligands may modulate these biological processes. It will additionally be important to determine whether these findings also occur in vivo, as similar results would have significant implications on the designs of molecularly targeted theranostics.

5. Experimental Section

Western Blots (WB)

M21 cells (1x106 cells/96-well plate) were grown in six wells coated with collagen (10 mg/ml), and made quiescent by growing under serum-deprived conditions. The medium was then changed to 0.2% FBS, and different concentrations (25–400 nM) of cRGDY-PEG-C-dots were added (37°C, 0.5–8 hours). Cells were rinsed twice in ice cold PBS, collected by trypsinization, and the pellet re-suspended in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH-8.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100), 1% Na deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, Complete™ protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail Tablet –PhosSTOP (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Lysates were centrifuged (10 min, 4°C). Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). A 50-μg protein aliquot of each fraction was separated by 4–12% gradient sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in Tris Buffered Saline (TBS)-Tween 0.1%, and signal visualized by ECL chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) or Immobilon Western, (Millipore Billerica, MA) after applying primary (1:1000) and secondary (1:2000 – 1:5000) antibodies. The experiment was repeated except that serum-deprived cells were exposed to two concentrations of PF-228 (i.e., 250 nM, 500 nM) one hour prior to addition of 100 nM cRGDY-PEG-C dots.

Cell cycle analysis

G0/G1-phase-synchronized M21 cells were incubated for 48 hours using two concentrations (100 and 300 nM) of cRGDY-PEG-C dots after changing the medium to 0.2% FCS. Following trypsinization, cells were centrifuged (1200 rpm, 5 min), and the pellet suspended in PBS, followed by fixation with 70% ethanol (4°C, 0.5–1 hour). Cells were successively re-suspended in 1 ml PBS containing 1% FCS and 0.1% Triton X-100, 200 μl PBS containing 25 μg/ml propidium iodide, and 100 mg/ml RNaseA (4°C, 60 minutes). Cell cycle analysis was performed by flow cytometry, using FACSCalibur (Mountain View, CA) and Phoenix Flow MultiCycle software (Phoenix Flow Systems, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Cell Proliferation

Cells were split (1x104 cells/well) in a 96-well plate coated with collagen as described for in-vitro cell binding studies. Different concentrations of cRGDY-PEG-C dots were added (25–200 nM) for 24–48 hours at 37°C. Then, 20 μl of the proliferation reagent WST-1 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) was added to the plate (37°C, 1 hour). For determination of optical densities, we used a SpectraMax5 micro plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Absorbance was measured at 440 nm.

Migration assay

M21 cells were seeded (6x104 cells/well) using a migration kit (Oris™ Collagen I coated plate, PLATYPUS TEC). Twenty-four hours after seeding the cells, stoppers in the plate were removed. Fresh culture media (100 μl) supplemented with 0.2% FBS was introduced and cRGDY-PEG-C-dots were added at several concentrations: 25, 100 and 400 nM. Every 24 hours thereafter, the medium was replaced, along with new particles, over a 72 hr time interval. Prior to incubating the plate at 37°C overnight, time zero images were captured by the Axiovert 200M microscope (Carl Zeiss) using a 5x (.15NA) objective and using a scan slide module in the Metamorph software (molecular devices, PA). Serial microscopy was then performed and images captured every 24 hrs for a total of 96 hours post-incubation to assess the percent areas of closure. The data were analyzed by using ImageJ software.

HUVEC cells

HUVEC cells were additionally seeded (5x104 cells/well) and, 24 hours later, incubated with several particle concentrations (100, 200, and 400 nM) after replacement of the media. The experiment was repeated in the presence of PF-228 one hour prior to addition of 400 nM cRGDY-PEG-C dots. A similar microscopy procedure was performed as that for M21 cells, with serial imaging acquired 20 hours later.

Adhesion and spreading assays

The effect of cRGDY-PEG-C dots on the binding of M21 cells to fibronectin coated plates was evaluated by initially coating 96–well micro titer plates with fibronectin in PBS (5 μg/ml), followed by 200 μl RPMI/0.5% BSA (37°C, 1 hour). Cells (1–3 × 104 cells/100 μl/well) were pre-incubated with or without 400 nM of cRGDY-PEG-C dots in RPMI/0.1% BSA (25°C, 30 minutes), and added to fibronectin-coated wells (37°C, 30–120 minutes). For quantification of the number of attached cells, wells were rinsed with RPMI/0.1% BSA to remove non-adherent cells. Adherent cells were fixed with 4% PFA (25°C, 20 minutes) and stained with methylene blue (37°C, 1 hour). The methylene blue was extracted from cells by the addition of 200 μl of 0.1 M HCl (37°C, 1 hour). Optical densities were determined using a SpectraMax5 micro plate reader, and absorbance was measured at 650 nm. For spreading assay: Time lapse was performed (37°C, 2 hours) and images were captured by Axiovert 200M microscope (Carl Zeiss) using a 20x (.15NA) objective and using a scan slide module in the Metamorph Software (Molecular Devices).

Quantitative analyses

In order to quantify the differences in the size and intensity between Western blot bands, we performed densitometry of phosphorylated and total protein intermediates using Photoshop CS2 (Adobe, San Jose, CA). Bands were scanned at 300 dpi (Scanjet 7650, Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA), and converted to grayscale. Regions of interest (ROI) were defined within the boundaries of each band in order to derive the following: area (number of pixels), mean grayscale value within the selected area (0–255) and the associated standard deviation. The product of the first two values for each band was computed, and divided by the product for the initial band in each set (control band), yielding an intensity value for each sample relative to the control. Finally the ratio of phosphorylated protein to total protein and the corresponding propagated error (SD) were computed for each sample using the relative intensities.

Phase contrast images captured for migration studies were analyzed using ImageJ 1.45s (National Institutes of Health, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) in order to quantify the extent of cell migration (i.e., area closure) for M21 cells and HUVECs. At high power views, an enclosed area was drawn adjacent to the rim of attached cells seen in each image after stopper removal. The enclosed area for each image was measured (pixels) and used to calculate percent closure relative to time zero (following particle addition and media replacement) as follows: difference in area at a given time point (24, 48, 72 or 96 hr) and at time zero divided by the same area at time zero multiplied by 100. The resulting values were averaged and a standard error computed for each group.

For cellular adhesion and spreading assays, cell counts in three high power fields per well were manually quantified and microscopically averaged. The assay was performed in quadruplicate at each time point.

Statistics

All graphical values are plotted as mean ± SE, except where noted. One-tailed Student’s t-test was used to test the statistical significance of differences in cellular migration between HUVECs or M21 cells incubated with serum alone or cRGDY-PEG-C dots. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to perform statistical pair-wise comparisons between the percentage of M21 cells in S phase that were incubated with serum alone, 100 nM or 300 nM cRGDY-PEG-C dots. We assigned statistical significance for all tests at P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Ow for supplying and characterizing fluorescent silica particles. This work was supported by an NIH/NCI R01CA129553 grant and a Research and Development award. Technical services provided by the MSKCC Flow Cytometry and Molecular Cytology Core Facilities, supported in part by the NIH Center Grant No P30 CA008748, are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Miriam Benezra, Department of Radiology, Sloan Kettering Institute for Cancer Research, New York, NY 10065, USA.

Evan Phillips, Department of Radiology, Sloan Kettering Institute for Cancer Research, New York, NY 10065, USA.

Michael Overholtzer, Department of Cell Biology, Sloan Kettering Institute for Cancer Research, New York, NY 10065, USA.

Pat B. Zanzonico, Department of Medical Physics, Sloan Kettering Institute for Cancer Research, New York, NY 10065, USA

Esa Tuominen, Department of Radiology, Sloan Kettering Institute for Cancer Research, New York, NY 10065, USA.

Prof. Ulrich Wiesner, Department of Materials Science & Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA

Michelle S. Bradbury, Email: bradburm@mskcc.org, Department of Radiology, Sloan Kettering Institute for Cancer Research, New York, NY 10065, USA

References

- 1.Caswell P, Norman J. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:257–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hynes RO. Cell. 2002;110:673–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hood JD, Cheresh DA. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:91–100. doi: 10.1038/nrc727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aplin AE, Howe A, Alahari SK, Juliano RL. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:197–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolos V, Gasent JM, Lopez-Tarruella S, Grande E. Onco Targets Ther. 2010;3:83–97. doi: 10.2147/ott.s6909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujii H, Nishikawa N, Komazawa H, Suzuki M, Kojima M, Itoh I, Obata A, Ayukawa K, Azuma I, Saiki I. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1998;16:94–104. doi: 10.1023/a:1006520220426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitjans F, Sander D, Adan J, Sutter A, Martinez JM, Jaggle CS, Moyano JM, Kreysch HG, Piulats J, Goodman SL. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 8):2825–38. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.8.2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks PC, Stromblad S, Klemke R, Visscher D, Sarkar FH, Cheresh DA. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1815–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI118227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eliceiri BP, Cheresh DA. Cancer J Sci Am. 2000;6:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh CH, Peng HC, Huang TF. Blood. 1998;92:3268–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felding-Habermann B, Mueller BM, Romerdahl CA, Cheresh DA. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:2018–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI115811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall JF, Nesbitt SA, Helfrich MH, Horton MA, Polakova K, Hart IR. Int J Cancer. 1991;49:924–31. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910490621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petitclerc E, Stromblad S, von Schalscha TL, Mitjans F, Piulats J, Montgomery AM, Cheresh DA, Brooks PC. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2724–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizejewski GJ. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1999;222:124–38. doi: 10.1177/153537029922200203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks PC, Montgomery AM, Rosenfeld M, Reisfeld RA, Hu T, Klier G, Cheresh DA. Cell. 1994;79:1157–64. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pampori N, Hato T, Stupack DG, Aidoudi S, Cheresh DA, Nemerow GR, Shattil SJ. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21609–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiosses WB, Shattil SJ, Pampori N, Schwartz MA. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:316–20. doi: 10.1038/35060120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caswell PT, Norman JC. Traffic. 2006;7:14–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caswell PT, Vadrevu S, Norman JC. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:843–53. doi: 10.1038/nrm2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones MC, Caswell PT, Norman JC. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:549–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pellinen T, Ivaska J. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3723–31. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duncan R, Richardson SC. Mol Pharm. 2012;9:2380–402. doi: 10.1021/mp300293n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sigismund S, Confalonieri S, Ciliberto A, Polo S, Scita G, Di Fiore PP. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:273–366. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caswell PT, Spence HJ, Parsons M, White DP, Clark K, Cheng KW, Mills GB, Humphries MJ, Messent AJ, Anderson KI, McCaffrey MW, Ozanne BW, Norman JC. Dev Cell. 2007;13:496–510. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White DP, Caswell PT, Norman JC. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:515–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caswell PT, Chan M, Lindsay AJ, McCaffrey MW, Boettiger D, Norman JC. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:143–55. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Deyne PG, O’Neill A, Resneck WG, Dmytrenko GM, Pumplin DW, Bloch RJ. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 18):2729–40. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.18.2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wickham TJ, Mathias P, Cheresh DA, Nemerow GR. Cell. 1993;73:309–19. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90231-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conner SD, Schmid SL. Nature. 2003;422:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nature01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiffelers RM, Ansari A, Xu J, Zhou Q, Tang Q, Storm G, Molema G, Lu PY, Scaria PV, Woodle MC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e149. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Temming K, Schiffelers RM, Molema G, Kok RJ. Drug Resist Updat. 2005;8:381–402. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellerby HM, Arap W, Ellerby LM, Kain R, Andrusiak R, Rio GD, Krajewski S, Lombardo CR, Rao R, Ruoslahti E, Bredesen DE, Pasqualini R. Nat Med. 1999;5:1032–8. doi: 10.1038/12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haubner R, Weber WA, Beer AJ, Vabuliene E, Reim D, Sarbia M, Becker KF, Goebel M, Hein R, Wester HJ, Kessler H, Schwaiger M. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e70. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slack-Davis JK, Martin KH, Tilghman RW, Iwanicki M, Ung EJ, Autry C, Luzzio MJ, Cooper B, Kath JC, Roberts WG, Parsons JT. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14845–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Danhier F, Le Breton A, Preat V. Mol Pharm. 2012;9:2961–73. doi: 10.1021/mp3002733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reynolds AR, Hart IR, Watson AR, Welti JC, Silva RG, Robinson SD, Da Violante G, Gourlaouen M, Salih M, Jones MC, Jones DT, Saunders G, Kostourou V, Perron-Sierra F, Norman JC, Tucker GC, Hodivala-Dilke KM. Nat Med. 2009;15:392–400. doi: 10.1038/nm.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stupp R, Ruegg C. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1637–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.8376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tucker GC. Curr Oncol Rep. 2006;8:96–103. doi: 10.1007/s11912-006-0043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reardon DA, Cheresh D. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:1159–65. doi: 10.1177/1947601912450586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roger Stupp MEH, Gorlia Thierry, Erridge Sara, Grujicic Danica, Steinbach Joachim Peter, Wick Wolfgang, Tarnawski Rafal, Nam Do-Hyun, Weyerbrock Astrid, Hau Peter, Taphoorn Martin JB, Nabors Louis B, Reardon David A, Van Den Bent Martin J, Perry James R, Hong Yong Kil, Hicking Christine, Picard Martin, Weller Michael on behalf of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), the Canadian Brain Tumor Consortium, and the CENTRIC Study Team, . J Clin Oncol. 2013;31 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hodivala-Dilke K. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:514–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hynes RO. Nat Med. 2002;8:918–21. doi: 10.1038/nm0902-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webb DJ, Donais K, Whitmore LA, Thomas SM, Turner CE, Parsons JT, Horwitz AF. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:154–61. doi: 10.1038/ncb1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gabarra-Niecko V, Schaller MD, Dunty JM. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:359–74. doi: 10.1023/a:1023725029589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitra SK, Hanson DA, Schlaepfer DD. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parsons JT. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1409–16. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sieg DJ, Hauck CR, Schlaepfer DD. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 16):2677–91. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.16.2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frisch SM, Vuori K, Ruoslahti E, Chan-Hui PY. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:793–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chithrani BD, Ghazani AA, Chan WC. Nano Lett. 2006;6:662–8. doi: 10.1021/nl052396o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang W, Kim BY, Rutka JT, Chan WC. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:145–50. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Osaki F, Kanamori T, Sando S, Sera T, Aoyama Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6520–1. doi: 10.1021/ja048792a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chithrani BD, Chan WC. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1542–50. doi: 10.1021/nl070363y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kam NW, Liu Z, Dai H. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:577–81. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmid SL, Carter LL. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2307–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Castel S, Pagan R, Mitjans F, Piulats J, Goodman S, Jonczyk A, Huber F, Vilaro S, Reina M. Lab Invest. 2001;81:1615–26. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garanger E, Boturyn D, Dumy P. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2007;7:552–8. doi: 10.2174/187152007781668706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gestwicki JE, Cairo CW, Strong LE, Oetjen KA, Kiessling LL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14922–33. doi: 10.1021/ja027184x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Benezra M, Penate-Medina O, Zanzonico PB, Schaer D, Ow H, Burns A, DeStanchina E, Longo V, Herz E, Iyer S, Wolchok J, Larson SM, Wiesner U, Bradbury MS. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2768–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI45600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schraa AJ, Kok RJ, Berendsen AD, Moorlag HE, Bos EJ, Meijer DK, de Leij LF, Molema G. J Control Release. 2002;83:241–51. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.