Infection by parasitic plants has been considered as an effective method for controlling invasive plants because the parasites partially or completely absorb water, nutrients, and carbohydrates from their host plants, suppressing the vitality of the host. Our study verified that younger and smaller Bidens pilosa plants suffer from higher levels of damage and are less likely to recover from infection by the parasitic plant Cuscuta australis than relatively older and larger plants, suggesting that Cuscuta australis is only a viable biocontrol agent for younger Bidens pilosa plants.

Keywords: Defence, deleterious effect, growth, invasive plant, parasitic plant

Abstract

Understanding changes in the interactions between parasitic plants and their hosts in relation to ontogenetic changes in the hosts is crucial for successful use of parasitic plants as biological controls. We investigated growth, photosynthesis and chemical defences in different-aged Bidens pilosa plants in response to infection by Cuscuta australis. We were particularly interested in whether plant responses to parasite infection change with changes in the host plant age. Compared with the non-infected B. pilosa, parasite infection reduced total host biomass and net photosynthetic rates, but these deleterious effects decreased with increasing host age. Parasite infection reduced the concentrations of total phenolics, total flavonoids and saponins in the younger B. pilosa but not in the older B. pilosa. Compared with the relatively older and larger plants, younger and smaller plants suffered from more severe damage and are likely less to recover from the infection, suggesting that C. australis is only a viable biocontrol agent for younger B. pilosa plants.

Introduction

A parasitic plant is a type of angiosperm (flowering plant) that directly attaches to another plant via a haustorium (Press 1998). Over 4500 known plant species are parasitic to some extent and acquire some or all of their water, carbon and nutrients from a host (Press 1998; Li et al. 2014). Parasitic plants are classified as stem or root parasites including facultative, hemiparasitic and holoparasitic forms (Yoder and Scholes 2010).

Infection by parasitic plants has been considered as an effective method for controlling invasive plants because the parasites partially (hemiparasites) or completely (holoparasites) absorb water, nutrients and carbohydrates from their host plants, suppressing the vitality of the host (Parker et al. 2006; Yu et al. 2008, 2009; Li et al. 2012). For example, the holoparasite Cuscuta australis, native to China, can inhibit the growth of Bidens pilosa, an invasive plant in China, and thus serve as an effective biological control agent for controlling the invasive B. pilosa (Zhang et al. 2012, 2013). Compared with the effects of feeding by herbivores, the defence responses of plants infected by parasitic plants have rarely been studied (Runyon et al. 2006; Ranjan et al. 2014), even though such knowledge is important for the successful use of parasitic plants as enemies against invasive plants.

It has been documented that plant defences to herbivore or pathogen damage vary with a plant's ontogenetic stages (Boege and Marquis 2006; Barton and Koricheva 2010; Tucker and Avila-Sakar 2010; Barton 2013). The ontogenetic patterns of plant defences were found to differ with plant life form (woody, herbaceous and grass, Barton and Koricheva 2010; Massad 2013), growth stage (seedlings, juveniles, mature plants, Barton and Koricheva 2010; Houter and Pons 2012; Barton 2013), development stage (flowering stage, fruiting stage, Tucker and Avila-Sakar 2010) and growth rate (slow-growing plant and fast-growing plant, Massad 2013). For herbaceous plants, for example, young plants are normally more heavily chemically defended than older ones (Cipollini and Redman 1999; Barton and Koricheva 2010; Massad 2013). However, as expected from the resource limitation hypothesis, the smaller reserves of resources stored in younger plants may negatively influence secondary metabolites in comparison with the larger resource reserves stored in mature plants, as expected from the resource limitation hypothesis (Bryant et al. 1991). Thus, younger plants may be less defended and less able to recover after herbivory or parasitic infestation (Hódar et al. 2008).

Similar to those defence reaction induced by herbivores and pathogens infection, plants may increase their chemical complexes to defend against parasitic infection through plant hormones, salicylic acid and jasmonic acid pathway (Runyon et al. 2010). Little attention has been paid to the ontogenetic changes of invasive plants inresponse to holoparasites. Wu et al. (2013) found that Cuscuta campestris seedlings cannot parasitize the invasive Mikania micrantha if the stem diameter of the host is ≥0.3 cm. Our field investigation found that the infestation rate of plants, such as B. pilosa, Solidago canadensis and Phytolacca americana, by C. australis decreased with increasing host age (data not shown). Accordingly, we conducted an experiment to understand the host defences in relation to host age in a holoparasite–host system. The growth characteristics and the concentrations of the main chemical defences were determined in different-aged invasive B. pilosa plants infected by C. australis to test the hypothesis that younger hosts are more easily damaged and less able to recover than the older ones because the younger plants with limited resource reserves have less capacity to produce chemical defences and to promote compensatory growth. We aimed to answer the following questions: (i) Do younger and older B. pilosa plants differ in their responses to infection by C. australis? (ii) Are these differences in responses are correlated with the growth of different-aged invasive host plants? The answers to these questions could provide basic scientific knowledge for using C. australis to manage the invasive plant B. pilosa.

Methods

Plant species

Bidens pilosa is native to the tropical America and has widely spread throughout China. It is an annual forb and can grow up to 1 m in height and produces numerous seeds every year, and it grows both in nutrient-rich and -poor soils. In November, 2009, seeds of B. pilosa were collected near Sanfeng temple (121°16′E, 28°88′N) in Linhai City, Zhejiang Province, China, and stored in a low-humidity storage cabinet (HZM-600, Beijing Biofuture Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology Development) until use.

Cuscuta australis, a native annual holoparasitic plant species to South China, and is considered a noxious weed of agriculture (Yu et al. 2011). It can infect a wide range of herbs and shrubs (e.g. plants in the families of Fabaceae and Asteraceae), including the invasive plants M. micrantha, Ipomoea cairica, Wedelia trilobata, Alternanthera philoxeroides and Bidens (Yu et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2012).

Experimental design

We conducted a greenhouse experiment at Taizhou University (121°17′E, 28°87′N) in Linhai City, Zhejiang Province, China. We sowed B. pilosa seeds in trays with sand to germinate in a greenhouse on 13 March, 22 March and 6 April 2011, to create three different-aged B. pilosa seedlings of three different ages. Approximately 20 days after sowing, B. pilosa seedlings (∼10 cm in height) were transplanted into pots (28 cm in inner diameter and 38 cm deep; 1 seedling per pot) filled with 2.5 kg yellow clay soil mixed with sand in a 2 : 1 ratio (v : v). Plant materials and stones were removed from the yellow clay soil collected from fields in Linhai. The soil mixture had a pH of 6.64 ± 0.01, with an organic matter content of 15.74 ± 2.65 g kg−1, available nitrogen of 0.27 ± 0.10 g kg−1, available phosphorus of 0.026 ± 0.004 g kg−1 and available potassium of 0.049 ± 0.003 g kg−1.

The pots were randomly placed in a greenhouse and irrigated with tap water twice daily. One week after transplantation, 2 g slow release fertilizer (Scotts Osmocote, N : P : K = 20 : 20 : 20, The Scotts Miracle-Gro Company, Marysville, OH, USA) was added to each pot.

On 5 June, when B. pilosa plants were of ages 59 days (mean height 32.0 cm and mean diameter 2.7 mm), 74 days (mean height 62.6 cm and mean diameter 5.1 mm) and 83 days old (mean height 93.3 cm and mean diameter 5.7 mm), plants were infected by C. australis manually. Three 15-cm long segments of parasitic C. australis stems collected from fields in Linhai were twined onto the stems of a B. pilosa plant to induce infection. After 24 h, most of C. australis successfully parasitized the host and died segments were substituted by new ones. For each age class, six individuals were infected and six plants were left intact as controls (n = 6). Six individuals were harvested, separated into shoots and roots, and then dried at 70 °C for 72 h, to determine the initial plant biomass (W1) at the beginning of infection (t1, i.e. 5 June).

Measurements

On 30 June 2011, i.e. after 26 days of infection, the net photosynthetic rate (Pn) of B. pilosa plants was determined on fully expanded, mature sun leaves in the upper canopy between 10:00 and 11:30 am, using a portable photosynthesis system (LI-6400/XT, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). For each measurement, three leaves per plant were chosen, and six consecutive measurements were performed.

On 9 July 2011 (t2), i.e. 35 days after infection, when C. australis was flowering and the host plants were 94, 109 and 118 days old, respectively, all plants were harvested. Cuscuta australis plants were separated from their hosts and dried at 70 °C for 72 h to determine the C. australis' biomass (Bc). The host plants were separated into leaves, stems and roots. Leaves, stems and roots of the host plants were dried at 70 °C for 72 h to determine their biomass (W2). The relative growth rate (RGR) of biomass was calculated with the equation RGR = (ln W2 − ln W1)/(t2 − t1) (González-Santana et al. 2012; Li et al. 2012).

The dried stems of the host plants were ground using a universal high-speed grinder (F80, Xinkang Medical Instrument Co. Ltd, Jiangyan, Jiangsu). The powder was filtered through a 20-mesh sieve and stored in a drier until chemical analysis.

Approximately 0.1 g of powder was extracted three times with 70 % ethanol (v/v) under reflux at 90 °C and the aqueous extract was used to measure the concentration of total phenolics and total flavonoids. The concentration of total phenolics and total flavonoids was determined using the Folin–Denis method and AlCl3 reaction method according to Cortés-Rojas et al. (2013) and Jin et al. (2007). Absorbance at 750 nm for total phenolics and 420 nm for total flavonoids was determined with a T6 UV–VIS spectrophotometer (Beijing Purkinje General Instrument Co. Ltd, Beijing, China). Gallic acid and rutin (purchased from National Institutes for Food and Drug Control, Beijing, China) were used as the standard for total phenolics and total flavonoids, respectively.

Approximately 0.1 g of powder was extracted three times with 70 % methanol under reflux at 70 °C, and the aqueous extract was used to measure the concentration of saponins and alkaloids. The concentration of total saponins and alkaloids was determined by a colourimetric method and bromocresol green reaction method, respectively, according to Li et al. (2006) and Jin et al. (2006). Absorbance at 560 nm (saponins) and 470 nm (alkaloids) was determined with a T6 UV–VIS spectrophotometer (Beijing Purkinje General Instrument Co. Ltd, Beijing, China). Ginsenosides-Re and berberin HCl (purchased from National Institutes for Food and Drug Control, Beijing, China) were used as the standard for saponins and alkaloids, respectively.

Approximately 0.1 g of powder was extracted three times with boiled water and the aqueous extract was used to measure the concentration of soluble tannin via the potassium permanganate redox titrations method according to Li et al. (2007). Gallic acid (purchased from National Institutes for Food and Drug Control, Beijing, China) was used as the standard.

Data analysis

The plastic responses (PR) of the host plants to parasite infection were calculated for all plant traits studied, using the equation PR = (VPP − MVC)/MVC (Barton 2008), where VPP is the value of a trait in a parasite-infected plant and MVC is the mean value of that trait in the same-aged controls. For example, if the mean biomass of the non-parasitized B. pilosa is A and the biomass of the parasitized B. pilosa is B, then PR = (B − A)/A. Such PR values reflect the relative changes in the host traits caused by parasites. A value of PR = 0 indicates no response. A value of PR < 0 indicates a negative response, whereas a value of PR > 0 indicates a positive response of the host to parasite infection.

The normality of the distribution and the homogeneity of the data were checked (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) before any further statistical analysis. A two-way ANOVA was used to analyse the effects of parasitism and host age on the host traits studied, followed by a one-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD analysis to test the difference in means within a parasite treatment and between the infected and non-infected plants. All tests were conducted at a significance level of P < 0.05 using SPSS (version 16.0).

Results

Effects of C. australis infection on host growth

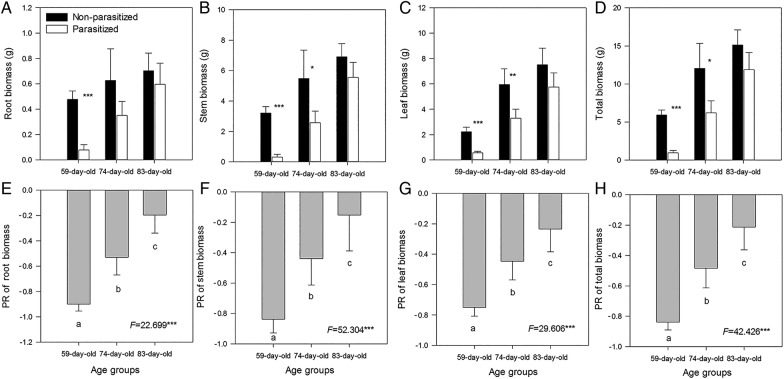

Cuscuta australis infection decreased the root, stem, leaf and total biomass of the hosts compared with the controls within each age class (Fig. 1, upper panel), and this negative effect on host growth significantly decreased with increasing host age (Fig. 1, lower panel). Compared with the non-infected control hosts, the total plant biomass of the infected hosts decreased 84 % for the 59-day-old plants, 48 % for the 74-day-old plants and 21 % for the 83-day-old plants.

Figure 1.

The root (A), stem (B), leaf (C) and total plant biomass (D) of different-aged invasive B. pilosa plants infected and not infected by C. australis, and the PR of the stem (E), root (F), leaf (G) and total plant biomass (H) of the infected B. pilosa plants. Values are given as means +1 SD (n = 6). Asterisks in the upper panel indicate significant difference in means between non-infected and infected plants within the same age class at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, respectively. Different letters in the lower panel indicate significant difference between PRs (P < 0.05).

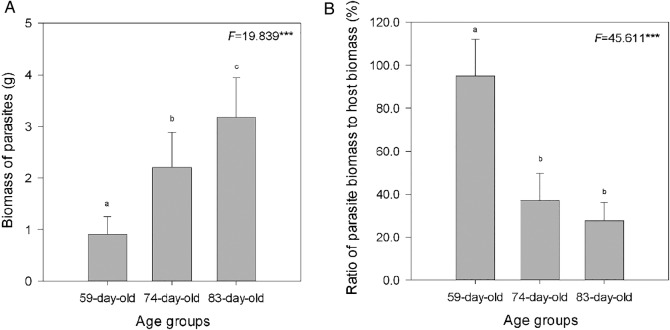

The growth of the parasites significantly increased with host age (Fig. 2A). However, the biomass ratio of parasite to host significantly decreased with host age (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

The biomass of parasites (A) of different-aged invasive B. pilosa plants, and the ratio of parasite biomass to host biomass (B). Values are given as means +1 SD (n = 6). Different letters indicate significant difference between host plants of different ages at P < 0.05. F-value and significance levels are given. ***Significant difference in means between plants within the same age class at P < 0.001.

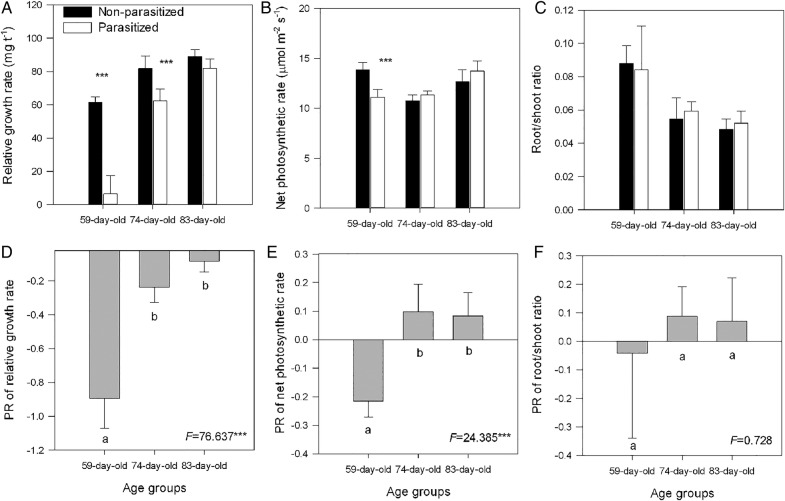

The infection of C. australis significantly decreased the growth rates in the younger (i.e. the 59- and 74-day-old hosts; both P < 0.001) but not in the 83-day-old hosts compared with those in the corresponding controls (Fig. 3A and D). The infection significantly suppressed the net photosynthetic rates only in the younger (59- and 74-day-old) hosts but not in the older hosts (Fig. 3B and E). Cuscuta australis infection had no effects on the root/shoot ratio in different-aged hosts (Fig. 3C), and the root/shoot ratio tended to decrease with increasing host age (Fig. 3C). The negative effect of C. australis infection on B. pilosa's RGRs (Fig. 3D), net photosynthetic rates (Fig. 3E) and root/shoot ratios (Fig. 3F) decreased with increasing host age (Fig. 3D–F). Host age (A) interacted with parasites (P) to affect the total biomass (P < 0.01 for A × P interaction), RGRs (P < 0.001) and net photosynthetic rates (P < 0.001) of the hosts (Table 1).

Figure 3.

The RGR (A), net photosynthetic rate of leaves (B) and root/shoot ratio (C) of different-aged invasive B. pilosa plants infected and not infected by C. australis, and the PR of RGR of plant biomass (D), net photosynthetic rate of leaves (E) and ratio of root biomass to shoot biomass (F) of different-aged invasive B. pilosa to the parasitic C. australis. Values are given as means +1 SD (n = 6). Different letters indicate significant difference between host plants of different ages at P < 0.05. F-value and significance levels are given. Asterisks indicate significant difference in means between plants within the same age class at ***P < 0.001.

Table 1.

Two-way ANOVA analysis of age and parasitism on the growth of invasive B. pilosa. Bold values indicate significant effects on the growth of B. pilosa.

| df | Leaf biomass |

Stem biomass |

Root biomass |

Total biomass |

Root/shoot ratio |

Relative growth rate |

Net photosynthetic rate |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | ||

| Age (A) | 2 | 97.135 | <0.001 | 59.992 | <0.001 | 19.819 | <0.001 | 121.986 | <0.001 | 23.926 | <0.001 | 175.610 | <0.001 | 29.308 | <0.001 |

| Parasitism (P) | 1 | 43.267 | <0.001 | 51.293 | <0.001 | 29.009 | <0.001 | 116.349 | <0.001 | 0.112 | 0.740 | 137.485 | <0.001 | 131.144 | <0.001 |

| A × P | 2 | 1.036 | 0.367 | 2.368 | 0.111 | 3.065 | 0.061 | 9.763 | <0.01 | 0.342 | 0.713 | 38.004 | <0.001 | 50.772 | <0.001 |

Effects of infection on host's secondary metabolites

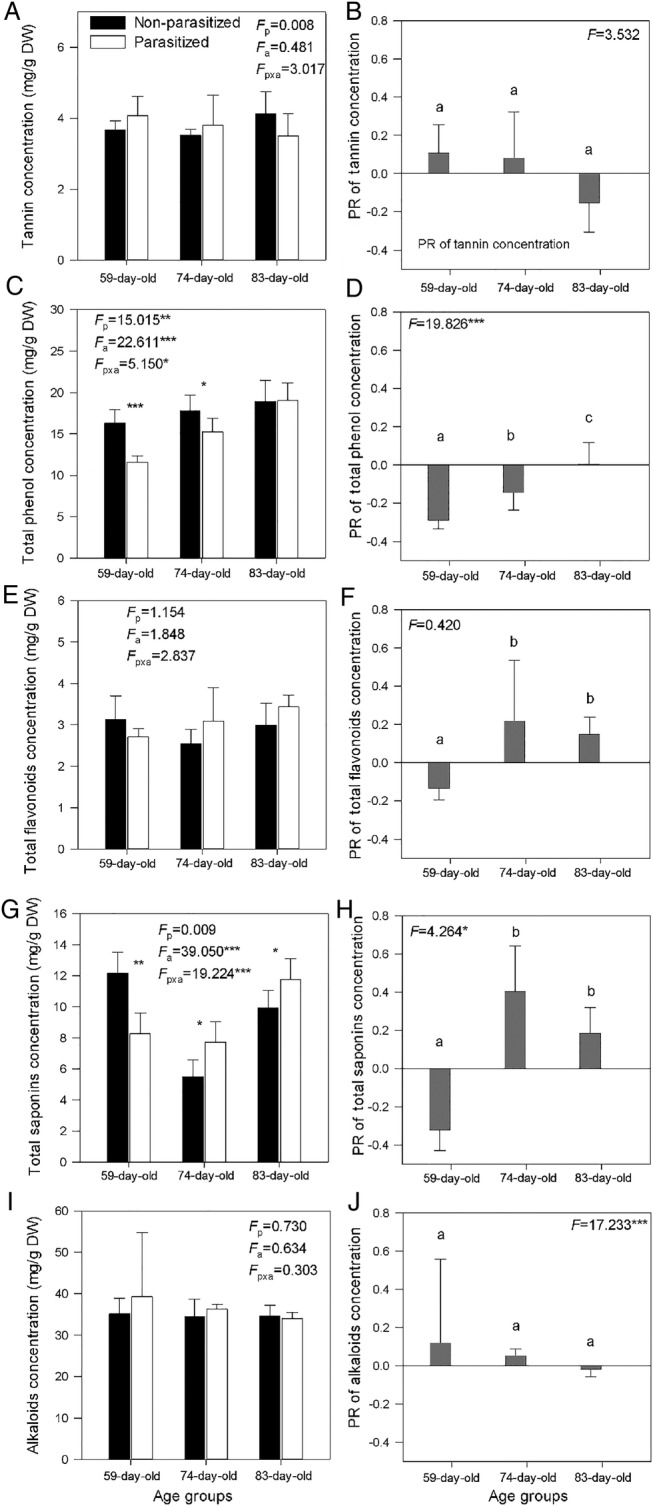

The infection significantly decreased the concentrations of the phenolics in the younger plants (59 and 74 days old) but not in the older hosts (Fig. 4C), and the negative effect of C. australis decreased with increasing host age (Fig. 4D). The infection significantly decreased the concentrations of the terpenoids in the younger plants (59 days old) but significantly increased those concentrations in the older plants (74 and 83 days old) (Fig. 4G). Host age interacted with parasite infection to influence the levels of total phenols and saponins (Fig. 4C and G). No effects of host age, parasite infection and their interaction on the concentrations of tannin, total flavonoids and alkaloids in the hosts were observed (Fig. 4A, E and I). The effect of infection on the concentration of total flavonoids in the younger plants was negative (59 days old), whereas that in the older plants was positive (74 and 83 days old) (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

The concentrations (mean values + 1 SD, n = 6) of tannin (A), total phenolics (C), total flavonoids (E), saponins (G) and alkaloids (I) in different-aged invasive B. pilosa plants infected and not infected by C. australis, and the PR of tannin (B), total phenolics (D), total flavonoids (F), saponins (H) and alkaloids (J) in stems of the different-aged B. pilosa plants to the parasitic C. australis. Different letters indicate significant difference between host plants of different ages at P < 0.05. F-value and significance levels are given. Asterisks indicate significant difference in means between plants within the same age class at *P <0.05, **P <0.01 and ***P < 0.001, respectively.

Discussion

Recovery ability in relation to the host age

The present study found that the deleterious effects of parasite infection on the older B. pilosa were significantly less severe than on the younger plants, indicating that the younger plants were more sensitive to parasite infection than the older ones. These results supported our hypothesis that the damage to younger B. pilosa caused by C. australis infection is greater than the damage to older B. pilosa.

Previous studies have shown that older hosts exhibit a defence mechanism that hampers the development of haustoria and thus mitigates parasite infection (Runyon et al. 2006; Meulebrouck et al. 2009; Lee and Jernstedt 2013). However, this conclusion was not supported by the present study because the parasite biomass did not decrease but increased with increasing host age in association with host size. Older hosts, with larger size and greater resource storage, could support greater growth of the attached parasites, leading to a mean increase in parasite biomass by 142 % for the 74-day-old hosts and 248 % for the 83-day-old hosts compared with that for the 59-day-old hosts.

Our study found that root, stem, leaf and total biomass, RGR and photosynthetic ability were significantly negatively affected by parasite infection in the younger plants (59 and 74 days old) but not in the older plants (83 days old), indicating that the young plants fail to compensate whereas the older plants do (Tan et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2012). Herbivory can induce compensatory growth by stimulating photosynthesis, altering mass allocation and increasing growth rates (Markkola et al. 2004; Hódar et al. 2008). Therefore, the responses of younger B. pilosa to parasite infection is not similar to the responses of plants to damage by herbivores (Barton and Koricheva 2010; Barton 2013). Stout et al. (2002) have found that younger rice plants appeared to be less tolerant to herbivory than older rice plants, though Elger et al. (2009) have reported a higher sensitivity to herbivore attacks in young seedlings of British grassland species than in older conspecifics.

Parasite infection had no effects on the root/shoot ratio in different-aged hosts, i.e. parasite infection did not alter the mass allocation to roots and shoots. This result may be due primarily to changes in the light conditions caused by the attack behaviour of the parasite. Herbivores destroy parts of plants, resulting in increases in light quality and quantity within a plant and thus leading to increases in photosynthesis and growth rates. In contrast, parasite infection may shade a host and decrease the light intensity within a host plant, especially if the hosts plants are small or young, thus leading to decreases in photosynthesis and growth rates (Rijkers et al. 2000).

The decreases in photosynthesis induced by parasitic infection led to a limited availability of resources, which further resulted in lower growth rates in smaller and younger hosts. These results indicated that the resistance of hosts to parasitic infection is negatively correlated with the availability of the resources stored in a host plant (Shen et al. 2013). For woody forest plants, negative effects of mistletoe infection on host tree growth and mortality have been consistently and extensively reported (Shaw et al. 2008; Logan et al. 2013), and those negative growth effects have widely been considered to result from decreased photosynthetic production (Meinzer et al. 2004) caused by decreased leaf size and leaf N content (Ehleringer et al. 1986; Cechin and Press 1993; Logan et al. 1999; Mishra et al. 2007).

Chemical defence relative to host age

Little attention has been paid to changes in chemical defences, such as alkaloids, phenolics, flavonoids, cyanogenic glycosides (Elger et al. 2009; Quintero and Bowers 2013), induced by parasitic infection, whereas ontogenetic changes in chemical defences against herbivory are well documented (Van Zandt and Agrawal 2004; Barton 2008). The concentrations of cyanogenic glycoside (Schappert and Shore 2000), nicotine (Ohnmeiss and Baldwin 2000), alkaloids (Ohnmeiss and Baldwin 2000; Elger et al. 2009) and phenolics (Donaldson et al. 2006; Elger et al. 2009) have been found to be higher in older tissues/plants than in younger tissues/plants exposed to herbivory. The present study found that the concentrations of total phenolics, total flavonoids and saponins were significantly negatively affected by C. australis infection in younger B. pilosa but not in older plants. A positive response of total phenolics was found only in the 83-day-old plants; a positive response of total flavonoids and saponins occurred in both 74- and 83-day-old plants. These results supported our initial hypothesis that the younger plants with limited resource reserves have less leeway to produce chemical defences. Similarly, it has been reported that older plants that had accumulated resources over a long period were better able to maintain anti-herbivore defences than younger plants with limited resources (Boege 2005; Elger et al. 2009).

However, other studies have reported opposite or neutral responses of chemical defences to herbivory (Thomson et al. 2003; Barton and Koricheva 2010). Goodger et al. (2013) demonstrated that the levels of phenolics produced in response to herbivory were highest in seedlings compared with those in juveniles and mature trees. A meta-analysis based on data from 36 published studies also did not find any clear relationships between ontogenetic stage and chemical defences induced by herbivory (Barton and Koricheva 2010). Ontogenetic patterns of plant chemical responses to herbivory or parasite infection might vary with plant species, chemical compounds and disturbance (e.g. parasite or insect infection) (Webber and Woodrow 2009; Rohr et al. 2010). Further studies are needed to identify, clarify and quantify the chemical defences in different hosts and different-aged hosts infected by different parasites.

Plant resistance traits, including physical defences traits and chemical secondary compounds, and tolerance traits such as compensatory re-growth are detectable, when plants are damaged by insect, pathogen or parasite infection (Stowe et al. 2000; Quintero and Bowers 2013). Previous studies prove that trade-offs between resistance and tolerance traits of plants do occur following damage (Orians et al. 2010; Quintero and Bowers 2013). However, several studies reported that the trade-offs between resistance and tolerance traits are not detectable for all development stages (e.g. Quintero and Bowers 2013), for example, during the seedling development stage (Barton 2008). Our results showed that younger hosts had higher concentrations of tannin and alkaloids but lower concentrations of flavonoids, phenolics and terpenoids, as well as a lower re-growth ability; conversely, older hosts had lower concentration of tannin and alkaloids, but higher concentrations of flavonoids, phenolics and terpenoids, as well as a higher capability of compensatory growth. These results provided an indirect evidence for supporting the above-mentioned viewpoints that younger hosts with lower biomass invest fewer resources in growth but more resources in higher concentrations of tannin and alkaloids, whereas the older hosts have a higher biomass and higher concentrations of flavonoids, phenolics and terpenoids, but lower concentrations of tannin and alkaloids. Accordingly, the overall pattern of response might depend on the age or size of the host and even on the diversity of damage.

In conclusion, the intensity of damage caused by the parasite C. australis was dependent on the host age or size associated with the host biomass, showing that younger and smaller hosts were more easily damaged and less able to recover. This result supported the resource limitation hypothesis (Bryant et al. 1991) because hosts with increasing host age (or size) have more resources available to defend against or limit the establishment of haustoria (Runyon et al. 2010). Our field investigation found that B. pilosa plants with a height >90 cm were resistant because they were less infected by C. australis, whereas B. pilosa plants with a height <30 cm were effectively and successfully controlled by C. australis. Our results, therefore, indicate that the parasite C. australis could be successfully used as a potential biological agent in the control of invasive B. pilosa plants only in the early stages of development. However, as Boege (2005) indicated, further studies are needed to better and fully understand the mechanisms underlying the effects of host ontogeny on the responses of the host plants to herbivores or (holo) parasites.

Sources of Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31270461; No. 30800133) and National Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. Y5110227).

Contributions by the Authors

J.L. and M.Y. conceived and designed research. B.Y., Q.Y. and J.Z. conducted experiments. J.L. analysed data. J.L. and M.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.

Footnotes

The running title has been amended.

Literature Cited

- Barton KE. 2008. Phenotypic plasticity in seedling defense strategies: compensatory growth and chemical induction. Oikos 117:917–925. 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2008.16324.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton KE. 2013. Ontogenetic patterns in the mechanisms of tolerance to herbivory in Plantago. Annals of Botany 112:711–720. 10.1093/aob/mct083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton KE, Koricheva J. 2010. The ontogeny of plant defense and herbivory: characterizing general patterns using meta-analysis. The American Naturalist 175:481–493. 10.1086/650722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boege K. 2005. Influence of plant ontogeny on compensation to leaf damage. American Journal of Botany 92:1632–1640. 10.3732/ajb.92.10.1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boege K, Marquis RJ. 2006. Plant quality and predation risk mediated by plant ontogeny: consequences for herbivores and plants. Oikos 115:559–572. 10.1111/j.2006.0030-1299.15076.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant JP, Provenza FD, Pastor J, Reichardt PB, Clausen TP, du Toit JT. 1991. Interactions between woody plants and browsing mammals mediated by secondary metabolites. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 22:431–446. 10.1146/annurev.es.22.110191.002243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cechin I, Press MC. 1993. Nitrogen relations of the sorghum-Sfriga hermonthica hostparasite association: growth and photosynthesis. Plant, Cell and Environment 16:237–247. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1993.tb00866.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cipollini DF, Jr, Redman AM. 1999. Age-dependent effects of jasmonic acid treatment and wind exposure on foliar oxidase activity and insect resistance in tomato. Journal of Chemical Ecology 25:271–281. 10.1023/A:1020842712349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Rojas DF, Chagas-Paula DA, da Costa FB, Souza CRF, Oliveira WP. 2013. Bioactive compounds in Bidens pilosa L. populations: a key step in the standardization of phytopharmaceutical preparations. Brazilian Journal of Pharmacognosy 23:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson JR, Kruger EL, Lindroth RL. 2006. Competition- and resource-mediated tradeoffs between growth and defensive chemistry in trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides). New Phytologist 169:561–570. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01613.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Cook CS, Tieszen LL. 1986. Comparative water use and nitrogen relationships in a mistletoe and its host. Oecologia 68:279–284. 10.1007/BF00384800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elger A, Lemoine DG, Fenner M, Hanley ME. 2009. Plant ontogeny and chemical defence: older seedlings are better defended. Oikos 118:767–773. 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17206.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González-Santana IH, Márquez-Guzmán J, Cram-Heydrich S, Cruz-Ortega R. 2012. Conostegia xalapensis (Melastomataceae): an aluminum accumulator plant. Physiologia Plantarum 144:134–145. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2011.01527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodger JQD, Heskes AM, Woodrow IE. 2013. Contrasting ontogenetic trajectories for phenolic and terpenoid defences in Eucalyptus froggattii. Annals of Botany 112:651–659. 10.1093/aob/mct010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hódar JA, Zamora R, Castro J, Gómez JM, García D. 2008. Biomass allocation and growth responses of Scots pine saplings to simulated herbivory depend on plant age and light availability. Plant Ecology 197:229–238. 10.1007/s11258-007-9373-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houter NC, Pons TL. 2012. Ontogenetic changes in leaf traits of tropical rainforest trees differing in juvenile light requirement. Oecologia 169:33–45. 10.1007/s00442-011-2175-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin ZX, Li JM, Zhu XY. 2006. The content analysis of total alkaloids in a rare and extincted plant Sinocalycanthus chinensis. Journal of Fujian Forestry Science and Technology 33:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jin ZX, Li JM, Zhu XY. 2007. Content of total flavonoids and total chlorogenic acid in the endangered plant Sinocalycanthus chinensis and their correlations with the environmental factors. Journal of Zhejiang University (Science Edition) 33:454–457. [Google Scholar]

- Lee KB, Jernstedt JA. 2013. Defense response of resistant host Impatiens balsamina to the parasitic angiosperm Cuscuta japonica. Journal of Plant Biology 56:138–144. 10.1007/s12374-013-0011-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Jin ZX, Zhu XY. 2006. Analysis and determination of total saponin content in an endangered plant Calycanthus chinensis. Journal of Northwest Forestry University 21:147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Jin ZX, Zhu XY. 2007. Comparison of the total tannin in different organs of Calycanthus chinensis. Guihaia 27:944–947. [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Jin Z, Song W. 2012. Do native parasitic plants cause more damage to exotic invasive hosts than native non-invasive hosts? An implication for biocontrol. PLoS ONE 7:e34577 10.1371/journal.pone.0034577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Jin ZX, Hagedorn F, Li MH. 2014. Short-term parasite-infection alters already the biomass, activity and functional diversity of soil microbial communities. Scientific Reports 4:6895–6902. 10.1038/srep06895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan BA, Demmig-Adams B, Rosenstiel TN, Adams WW., III 1999. Effect of nitrogen limitation on foliar antioxidants in relationship to other metabolic characteristics. Planta 209:213–220. 10.1007/s004250050625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan BA, Reblin JS, Zonana DM, Dunlavey RF, Hricko CR, Hall AW, Schmiege SC, Butschek RA, Duran KL, Emery RJN, Kurepin LV, Lewis JD, Pharis RP, Phillips NG, Tissue DT. 2013. Impact of eastern dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium pusillum) on host white spruce (Picea glauca) development, growth and performance across multiple scales. Physiologia Plantarum 147:502–513. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01681.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markkola A, Kuikka K, Rautio P, Härmä E, Roitto M, Tuomi J. 2004. Defoliation increases carbon limitation in ectomycorrhizal symbiosis of Betula pubescens. Oecologia 140:234–240. 10.1007/s00442-004-1587-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massad TJ. 2013. Ontogenetic differences of herbivory on woody and herbaceous plants: a meta-analysis demonstrating unique effects of herbivory on the young and the old, the slow and the fast. Oecologia 172:1–10. 10.1007/s00442-012-2470-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinzer FC, Woodruff DR, Shaw DC. 2004. Integrated responses of hydraulic architecture, water and carbon relations of western hemlock to dwarf mistletoe infection. Plant, Cell and Environment 27:937–946. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01199.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meulebrouck K, Verheyen K, Brys R, Hermy M. 2009. Limited by the host: host age hampers establishment of holoparasite Cuscuta epithymum. Acta Oecologica 35:533–540. 10.1016/j.actao.2009.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra JS, Moorthy BTS, Bhan M, Yaduraju NT. 2007. Relative tolerance of rainy season crops to field dodder (Cuscuta campestris) and its management in niger (Guizotia abyssinica). Crop Protection 26:625–629. 10.1016/j.cropro.2006.05.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnmeiss TE, Baldwin IT. 2000. Optimal defense theory predicts the ontogeny of an induced nicotine defense. Ecology 81:1765–1783. 10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[1765:ODTPTO]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orians CM, Hochwender CG, Fritz RS, Snäll T. 2010. Growth and chemical defense in willow seedlings: trade-offs are transient. Oecologia 163:283–290. 10.1007/s00442-009-1521-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JD, Burkepile DE, Hay ME. 2006. Opposing effects of native and exotic herbivores on plant invasions. Science 311:1459–1461. 10.1126/science.1121407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press MC. 1998. Dracula or Robin Hood? A functional role for root hemiparasites in nutrient poor ecosystems. Oikos 82:609–611. 10.1126/science.1121407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero C, Bowers MD. 2013. Effects of insect herbivory on induced chemical defences and compensation during early plant development in Penstemon virgatus. Annals of Botany 112:661–669. 10.1093/aob/mct011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan A, Ichihashi Y, Farhi M, Zumstein K, Townsley B, David-Schwartz R, Sinha NR. 2014. De novo assembly and characterization of the transcriptome of the parasitic weed dodder identifies genes associated with plant parasitism. Plant Physiology 166:1186–1199. 10.1104/pp.113.234864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijkers T, Pons TL, Bongers F. 2000. The effect of tree height and light availability on photosynthetic leaf traits of four neotropical species differing in shade tolerance. Functional Ecology 14:77–86. 10.1046/j.1365-2435.2000.00395.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohr JR, Raffel TR, Hall CA. 2010. Developmental variation in resistance and tolerance in a multi-host-parasite system. Functional Ecology 24:1110–1121. 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01709.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Runyon JB, Mescher MC, De Moraes CM. 2006. Volatile chemical cues guide host location and host selection by parasitic plants. Science 313:1964–1967. 10.1126/science.1131371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyon JB, Mescher MC, Felton GW, de Moraes CM. 2010. Parasitism by Cuscuta pentagona sequentially induces JA and SA defence pathways in tomato. Plant, Cell and Environment 33:290–303. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02082.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schappert PJ, Shore JS. 2000. Cyanogenesis in Turnera ulmifolia L. (Turneraceae). II. Developmental expression, heritability and cost of cyanogenesis. Evolutionary Ecology Research 2:337–352. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DC, Huso M, Bruner H. 2008. Basal area growth impacts of dwarf mistletoe on western hemlock in an old-growth forest. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 38:576–583. 10.1139/X07-174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Xu SJ, Hong L, Wang ZM, Ye WH. 2013. Growth but not photosynthesis response of a host plant to infection by a holoparasitic plant depends on nitrogen supply. PLoS ONE 8:e7555 10.1371/annotation/e2536fcb-3ab3-44a0-8eab-91aaeb8e49b6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout MJ, Rice WC, Ring DR. 2002. The influence of plant age on tolerance of rice to injury by the rice water weevil, Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Bulletin of Entomological Research 92:177–184. 10.1079/BER2001147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe KA, Marquis RJ, Hochwender CG, Simms EL. 2000. The evolutionary ecology of tolerance to consumer damage. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 31:565–595. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.565 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan DY, Guo SL, Wang CL, Ma C. 2004. Effects of the parasite plant (Cistanche deserticola) on growth and biomass of the host plant (Haloxylon ammodendron). Forest Research 17:472–478. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson VP, Cunningham SA, Ball MC, Nicotra AB. 2003. Compensation for herbivory by Cucumis sativus through increased photosynthetic capacity and efficiency. Oecologia 134:167–175. 10.1007/s00442-002-1102-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker C, Avila-Sakar G. 2010. Ontogenetic changes in tolerance to herbivory in Arabidopsis. Oecologia 164:1005–1015. 10.1007/s00442-010-1738-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zandt PA, Agrawal AA. 2004. Specificity of induced plant responses to specialist herbivores of the common milkweed Asclepias syriaca. Oikos 104:401–409. 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.12964.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RK, Guang M, Li YH, Yang BF, Li JM. 2012. Effect of the parasitic Cuscuta australis on the community diversity and the growth of Alternanthera philoxeroides. Acta Ecologica Sinica 32:1917–1923. 10.5846/stxb201102280240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webber BL, Woodrow IE. 2009. Chemical and physical plant defence across multiple ontogenetic stages in a tropical rain forest understorey tree. Journal of Ecology 97:761–771. 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01512.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Guo Q, Li MG, Jiang L, Li FL, Zan QJ, Zheng J. 2013. Factors restraining parasitism of the invasive vine Mikania micrantha by the holoparasitic plant Cuscuta campestris. Biological Invasions 15:2755–2762. 10.1007/s10530-013-0490-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder JI, Scholes JD. 2010. Host plant resistance to parasitic weeds; recent progress and bottlenecks. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 13:478–484. 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Yu FH, Miao SL, Dong M. 2008. Holoparasitic Cuscuta campestris suppresses invasive Mikania micrantha and contributes to native community recovery. Biological Conservation 141:2653–2661. 10.1016/j.biocon.2008.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, He WM, Liu J, Miao SL, Dong M. 2009. Native Cuscuta campestris restrains exotic Mikania micrantha and enhances soil resources beneficial to natives in the invaded communities. Biological Invasions 11:835–844. 10.1007/s10530-008-9297-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Liu J, He WM, Miao SL, Dong M. 2011. Cuscuta australis restrains three exotic invasive plants and benefits native species. Biological Invasions 13:747–756. 10.1007/s10530-010-9865-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Yan M, Li JM. 2012. Effect of differing levels parasitism from native Cuscuta australis on invasive Bidens pilosa growth. Acta Ecologica Sinica 32:3137–3143. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Li JM, Yan M. 2013. Effects of nutrients on the growth of the parasitic plant Cuscuta australis R.Br. Acta Ecologica Sinica 33:2623–2631. 10.5846/stxb201201140082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]