Abstract

Background

Long-term data on outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stent (DES) and bare-metal stent (BMS) across racial groups are limited, and minorities are under-represented in existing clinical trials. Whether DES has better long-term clinical outcomes compared to BMS across racial groups remains to be established. Accordingly, we assessed whether longer-term clinical outcomes are better with DES compared to BMS across racial groups.

Methods

Using the multicenter National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)-sponsored Dynamic Registry, 2-year safety (death, MI) and efficacy (repeat revascularization) outcomes of 3,326 patients who underwent PCI with DES versus BMS were evaluated.

Results

With propensity-score adjusted analysis, the use of DES, compared to BMS, was associated with a lower risk for death or MI at 2 years for both blacks (adjusted Hazard Ratio (aHR)=0.41, 95% CI 0.25–0.69, p<0.001) and whites (aHR=0.67, 95% CI 0.51–0.90, p=0.007). DES use was associated with a significant 24% lower risk of repeat revascularization in whites (aHR=0.76, 95% CI 0.60–0.97, p=0.03) and with nominal 34% lower risk in blacks (aHR=0.66, 95% CI 0.39–1.13, p=0.13).

Conclusion

Use of DES in PCI was associated with better long-term safety outcomes across racial groups. Compared to BMS, DES was more effective in reducing repeat revascularization in whites and blacks, but this benefit was attenuated after statistical adjustment in blacks. These findings indicate that DES is superior to BMS in all patients regardless of race. Further studies are needed to determine long-term outcomes across racial groups with newer generation stents.

Keywords: Coronary stents, Long term outcomes, Race, Disparity

INTRODUCTION

Drug eluting stents (DES) are superior to bare metal stents (BMS) in reducing incidence of in-stent restenosis and the need for repeat revascularization, but are not associated with decreased incidence of death or myocardial infarction (MI), in randomized clinical trials.1–4 Analyses of data from real-world patients enrolled in registries suggest that DES use, compared with BMS, are not only associated with lower rates of repeat revascularization, but also, lower rates of death and MI.5 These benefits appear to be driven primarily by a reduction in the incidence of in-stent restenosis and the need for repeat revascularization.5 Despite the marked efficacy demonstrated by DES in reducing the need for repeat revascularization,5 some concerns have emerged regarding the long-term safety of DES6–9 with some studies indicating that DES use is associated with increased incidence of stent thrombosis and MI, especially among blacks.8,9 Whether DES has better long-term clinical outcomes compared with BMS in blacks and whites remains to be established.

Blacks have more comorbid conditions and present at younger age for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), compared with their white counterparts.10 Although in-hospital outcomes are similar in blacks and whites, higher 1-year mortality have been observed in blacks.10–12 Data on minority populations are limited because of under-representation of minorities in the existing randomized clinical trials including those evaluating PCI outcomes.1–4, 6 Therefore, little is known about the safety of DES, in relation to BMS, among minority populations, particularly blacks. Accordingly, the purpose of this study is to assess whether longer-term clinical outcomes are better with DES compared to BMS across racial groups using the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Dynamic Registry.

METHODS

NHLBI Registry Design

The NHLBI Dynamic Registry has been previously described in detail.13, 14 In brief, the Dynamic Registry, coordinated at the University of Pittsburgh, involves multi-center recruitment of consecutive patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) at 27 clinical centers in North America during pre-specified time intervals or “waves”. Each clinical center received approval from its institutional review board. Five recruitment waves of approximately 2000 patients were enrolled and followed over a 10-year period (wave 1: 1997 to 1998, n=2524 patients; wave 2: 1999, n=2105 patients; wave 3: 2001 to 2002, n=2047 patients; wave 4: 2004, n=2112 patients; and wave 5: 2006, n=2176 patients). Only BMS were available during the recruitment period for waves 1, 2, 3, and DES were introduced prior to the start of wave 4.

Data on baseline demographic, clinical and angiographic characteristics and procedural characteristics during the index PCI, as well as the occurrence of death, myocardial infarction, and the need for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) were collected. In-hospital and 24-month follow-up data were obtained by research coordinators using standardized report forms. Coordinators periodically evaluated the vital status of patients who were lost to follow-up using the Social Security Administration’s Death Master File (www.Ntis.gov/products/ssa-dmf.asp). If patients underwent subsequent repeat revascularization (either PCI or CABG), vessel –specific and lesion –specific data were collected whenever possible to determine target-vessel revascularization.

Study Population

The present study cohort was divided into two racial groups in accordance with the Congressional Office of Management and Budget, and based on patient’s self-description of their race as black or African American, and as white or Caucasian. Multiple racial/ethnic groups were not allowed and patients reporting a race other than black or white were excluded for this analysis. We further subdivided these two groups of patients into those that received BMS and those that received DES. Given that this analysis evaluated outcomes beyond one year, the patients enrolled in recruitment waves 1 and 3 were excluded due to the shorter maximum follow-up. To reduce a potential treatment bias, only data from centers with at least 5% black population were included in this analysis. Finally, only patients receiving at least one stent were included.

Endpoints

The end points were death from any cause, MI, and repeat revascularization. Safety endpoints were death and MI, and efficacy endpoint was repeat revascularization. MI was diagnosed on the basis of evidence of at least two of the following: typical chest pain lasting more than 20 minutes and not relieved by nitroglycerine; serial electrocardiograms showing changes from baseline or serially in ST and T waves, Q-waves, or both in more than two contiguous leads; a rise in the creatine kinase (CK) level to more than twice the upper limit of the normal range with an increase in CK-MB of more than 5% of the total value; and an elevation in the troponin level to more than twice the upper limit of the normal range. Repeat revascularization was defined as the combined end point of repeat PCI or CABG during the follow-up period. Repeat PCI included revascularization of target lesions and target vessels but did not included staged procedures. Only definite stent thrombosis, defined as angiographically confirmed cases, is reported in this study. Stent thrombosis events were captured only in waves 4 and 5, and all were independently adjudicated. Stent thrombosis events that occurred in stents placed after the index procedure were not included in this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

For each race category, patient characteristics pertaining to the index PCI, including demographic characteristics, medical history, cardiac presentation, peri-procedural medications, procedural characteristics, and in-hospital outcomes were compared between stent types and race using the Student’s t-tests or Wilcoxon nonparametric tests for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Similar methods were used for lesion-level analyses. Two year cumulative incidence rates of individual clinical outcomes and composite outcomes were estimated by the Kaplan – Meier method and tested by the log-rank statistic. Patients who did not experience the outcome of interest were censored at the last known date of contact or at 2-years if contact extended beyond 2 years. To complement these analyses, stratified analyses and formal test for interaction were performed to evaluate whether the association between stent type and clinical outcomes varied by race.

Multivariable Cox proportional-hazards regression modeling was used to estimate the independent effect of stent type (DES vs. BMS) in both black and white patients. A propensity score approach was used to balance factors associated with the nonrandom assignment of stent type. Logistic regression was used initially to identify the variables to include in each propensity score (one for blacks and one for whites). The models were conservative, such that it included variables with a p-value <0.20. A probability score was created for each study participant using parameter estimates for the variables in the model. All statistical analyses were performed with the use of SAS software, version 9.1 and a two-sided P value of 0.05 or less was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

A total of 3,326 patients (718 blacks (21.6%) and 2608 whites (78.4%)) received stents. Among blacks, 543 (75.6%) were treated with DES and 175 (24.4%) were treated with BMS, while the whites consisted of 1946 (74.6%) treated with DES and 662 (25.4%) treated with BMS. Table 1 lists baseline characteristics. For both blacks and whites, there were no significant differences in age, or prevalence of prior MI, cerebrovascular and peripheral vascular disease between those treated with DES and BMS, but black and white patients who were treated with DES compared to those treated with BMS were more likely to have severe non-cardiac comorbid conditions, renal disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and a higher mean body mass index (Table 1). White patients who received DES, compared to BMS, were more likely to have diabetes, >50% stenosis in left main, left anterior descending and circumflex artery, and more likely to have disease amenable to revascularization by CABG. While blacks treated with DES, compared to BMS, were more likely to present with a total occlusion and disease amenable to revascularization by PCI (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors by Race

| Black | White | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMS (N=175) | DES (N=543) | p-value | BMS (N=662) | DES (N=1946) | p-value | ||

| Age, mean, years | 59.3 | 61.4 | .056 | 63.7 | 64.5 | 0.127 | |

| Female, % | 49.7 | 44.0 | 0.188 | 36.1 | 29.4 | 0.001 | |

| BMI, mean, kg/m2 | 29.1 | 30.4 | 0.02 | 28.6 | 29.4 | 0.007 | |

| Prior PCI, % | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 77.7 | 70.0 | 0.01 | 71.0 | 64.0 | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 22.3 | 30.0 | 29.0 | 36.0 | |||

| Prior MI, % | 27.2 | 22.9 | 0.255 | 26.6 | 23.7 | 0.137 | |

| Severe non-cardiac comorbidity, % | 34.9 | 41.6 | 0.009 | 31.4 | 39.0 | <0.001 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease, % | 5.7 | 10.0 | 0.086 | 5.5 | 7.5 | 0.072 | |

| Renal disease, % | 9.1 | 15.3 | 0.040 | 4.7 | 8.6 | 0.001 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease, % | 8.6 | 8.9 | 0.908 | 7.9 | 8.7 | 0.510 | |

| Pulmonary disease, % | 5.7 | 9.2 | 0.145 | 8.6 | 9.4 | 0.543 | |

| Cancer, % | 4.6 | 6.6 | 0.321 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 0.641 | |

| Congestive heart failure, % | 9.7 | 13.5 | 0.185 | 8.2 | 9.5 | 0.331 | |

| Hypertension, % | 78.7 | 86.7 | 0.011 | 63.4 | 77.6 | <.001 | |

| Diabetes, % | 36.2 | 43.8 | 0.076 | 27.0 | 33.6 | 0.002 | |

| Hypercholesterolemia, % | 48.8 | 76.7 | <0.001 | 58.0 | 79.3 | <.001 | |

| Smoking, % | |||||||

| Never | 30.8 | 30.2 | 0.014 | 36.0 | 34.1 | 0.399 | |

| Current | 40.7 | 30.2 | 25.1 | 23.9 | |||

| Former | 20.5 | 39.5 | 39.0 | 42.0 | |||

| Former/never | 59.3 | 69.8 | 0.003 | 74.9 | 76.1 | 0.035 | |

| Current | 40.7 | 30.2 | 25.1 | 23.9 | |||

BMI indicates body mass index; BMS, bare metal stent; DES, drug eluting stent; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 2.

Angiographic Characteristics by Race

| Black | White | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMS (N=175) | DES (N=543) | p-value | BMS (N=662) | DES (N=1946) | p-value | ||

| LVEF, mean, % | 50.6 | 50.0 | 0.926 | 50.9 | 52.2 | 0.009 | |

| Abnormal LVEF, % | 28.8 | 32.6 | 0.414 | 29.1 | 29.1 | 0.998 | |

| Coronary Lesion location | |||||||

| RCA only, % | 14.6 | 11.0 | 0.2076 | 15.7 | 10.5 | 0.0005 | |

| LAD only, % | 21.1 | 21.1 | 0.9889 | 22.2 | 19.1 | 0.0833 | |

| LCx only, % | 5.8 | 10.6 | 0.0626 | 7.2 | 6.6 | 0.6493 | |

| RCA+LAD+LCx | 22.3 | 24.7 | 0.5199 | 22.2 | 31.7 | <.0001 | |

| Number of vessel diseased, > 50 % | 0.3062 | <.0001 | |||||

| Single-vessel, % | 40.6 | 41.4 | 43.8 | 34.0 | |||

| Double-vessel, % | 35.4 | 33.0 | 32.8 | 32.8 | |||

| Three-vessel, % | 23.4 | 25.6 | 23.0 | 33.0 | |||

| % with stenosis >50% | |||||||

| LM | 2.3 | 3.1 | 0.5640 | 2.9 | 6.2 | 0.0010 | |

| LAD | 66.9 | 69.1 | 0.5852 | 68.3 | 75.2 | 0.0005 | |

| Lcx | 50.3 | 54.7 | 0.309 | 46.2 | 56.1 | <.0001 | |

| RCA | 62.9 | 58.9 | 0.3569 | 62.2 | 65.0 | 0.2075 | |

| Graft | 9.1 | 8.7 | 0.842 | 13.1 | 13.9 | 0.6126 | |

| Any total occlusions | 28.6 | 37.0 | 0.0416 | 33.7 | 36.2 | 0.2474 | |

| Amenable to complete revascularization by PCI | 79.9 | 91.8 | <0.001 | 88.3 | 88.9 | 0.6947 | |

| Amenable to complete revascularization by CABG | 83.3 | 76.2 | 0.070 | 88.3 | 84.3 | 0.0211 | |

BMS indicates bare metal stent; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; DES, drug eluting stent; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCx, left circumflex artery; LM, left main; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery.

Procedural and Lesion Characteristics

For both blacks and whites, DES-treated patients were more likely to have calcified lesions, less likely to present with unstable angina, and to receive procedural antithrombotic therapy compared to BMS-treated patients. Among the black patients, there was greater use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in the DES-treated patients, although there were no significant difference in the urgency of the procedure between DES and BMS groups. Among white patients, DES-treated patients had longer lesion length and higher proportion of ACC/AHA type C lesions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Procedural and Lesion Characteristics by Race and Type of Stent Received

| Black | White | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMS (N=175) | DES (N=543) | p-value | BMS (N=662) | DES (=1946 | p-value | |

| Revascularization reason | ||||||

| Asymptomatic Coronary Artery Disease, % | 2.9 | 13.4 | <.0001 | 7.3 | 15.3 | <.0001 |

| Stable Angina, % | 13.1 | 17.7 | 0.1604 | 13.9 | 22.8 | <.0001 |

| Unstable Angina, % | 48.0 | 33.1 | 0.0004 | 50.9 | 34.6 | <.0001 |

| Acute MI, % | 33.1 | 31.5 | 0.6836 | 24.2 | 23.3 | 0.6406 |

| Other, % | 2.9 | 1.1 | 0.1008 | 2.7 | 0.7 | <.0001 |

| Cardiogenic shock, % | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.2524 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.1236 |

| Thrombolitic therapy, % | 11.4 | 2.2 | <.0001 | 6.3 | 3.5 | 0.0016 |

| Circumstances of procedures, % | ||||||

| Elective | 52.6 | 49.4 | 0.7592 | 45.3 | 59.1 | <.0001 |

| Urgent | 34.9 | 37.4 | 43.1 | 31.1 | ||

| Emergent | 12.6 | 13.3 | 11.6 | 9.7 | ||

| IIb/IIIa Receptor Antagonist, % | 28.0 | 40.5 | 0.0029 | 37.9 | 37.7 | 0.9093 |

| Lesions | (n=235) | (n=755) | (n=969) | (n=2706) | ||

| ACC/AHA Classification, % | ||||||

| A | 15.4 | 13.0 | 0.3898 | 7.6 | 11.4 | <.0001 |

| B1 | 34.8 | 33.1 | 34.9 | 31.5 | ||

| B2 | 32.6 | 31.7 | 45.5 | 30.2 | ||

| C | 17.2 | 22.2 | 12.0 | 26.8 | ||

| Reference vessel size, overall, mean | 3.1, 3 | 3.0, 3 | 0.0158 | 3.0, 3 | 3.0, 3 | 0.6451 |

| Lesion Length, mean, | 15.1 | 16.6 | 0.6555 | 14.2, 13 | 17.5, 15 | <.0001 |

| Diameter % Stenosis, mean, | 86.7 | 83.4 | <.0001 | 83.9, 89 | 83.4, 81 | 0.0092 |

| Evidence of Thrombus, % | 19.6 | 14.9 | 0.0869 | 19.2 | 12.3 | <.0001 |

| Calcified, % | 13.7 | 24.9 | 0.0003 | 14.5 | 29.3 | <.0001 |

| Ulcerated, % | 11.6 | 13.9 | 0.3715 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 0.9836 |

| Bifurcation, % | 11.5 | 8.9 | 0.2318 | 18.5 | 10.3 | <.0001 |

BMS indicates bare metal stent; DES, drug eluting stent; MI, myocardial infarction.

Clinical Outcomes

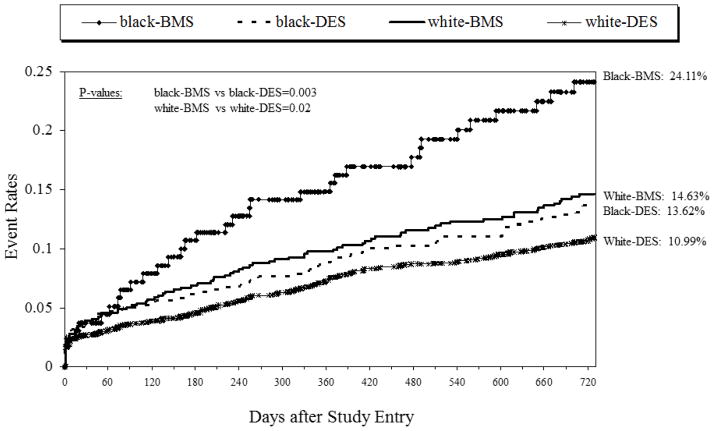

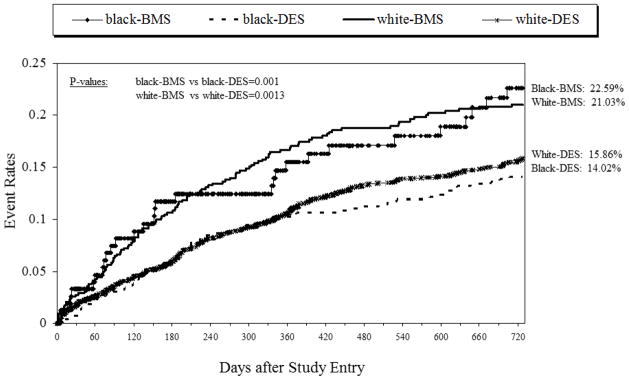

As shown in Table 4 and depicted in Figures 1 and 2, there were significant differences in revascularization outcomes between patients receiving DES vs. BMS, regardless of race. Compared to BMS, the use of DES was associated with significantly lower rates in the need for repeat revascularization (CABG and PCI) by 2-years in blacks (14.02 vs. 22.59, p=0.001) and whites (15.86 vs. 21.03, p=0.001) (Figure 1). This overall efficacy benefit appears to be driven by a lower incidence of CABG (Blacks, 2.2 vs 9.5, p=0.0001; Whites, 2.5 vs 6.9, p=0.0001). Similarly, DES use was associated with significantly lower rates of the combined safety outcome (death or MI) by 2-years in blacks (13.62 vs. 24.11, p=0.003) and whites (10.99 vs. 14.63, p=0.02) (Figure 2). This benefit appears to be driven by lower rates of death (blacks, 8.54 vs 15.18, p=0.02; whites, 6.39 vs. 8.86, p=0.03) in those receiving DES compared to BMS. As shown in Table 4, formal tests of interaction between race and stent type on clinical outcomes were not significant.

Table 4.

Cumulative Events Rates for Two Year Follow-up

| Follow-up Events | black-BMS (N=175) | black-DES (N=543) | white-BMS (N=662) | white-DES (N=1946) | p_value Stent*Race |

p_value White-BMS vs DES |

p_value Black-BMS vs DES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | ||||

| Death | 15.18 | 8.54 | 8.86 | 6.39 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| MI | 10.10 | 6.57 | 7.11 | 5.75 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.21 |

| CABG | 9.52 | 2.22 | 6.98 | 2.55 | 0.31 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Repeat PCI after discharge | 16.29 | 12.43 | 16.22 | 13.88 | 0.83 | 0.11 | 0.30 |

| Death/MI | 24.11 | 13.62 | 14.63 | 10.99 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.003 |

| Repeat Revascularization | 22.59 | 14.02 | 21.03 | 15.86 | 0.48 | 0.0013 | 0.001 |

| Death/MI/repeat revascularization | 35.28 | 22.17 | 31.16 | 23.09 | 0.43 | 0.0001 | 0.0017 |

BMS indicates bare metal stent; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; DES, drug eluting stent; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; Stent*Race, stent type and race interaction. Cumulative event rates were calculated via the Kaplan-Meier method. The events are censored at 731 days.

Figure 1.

Two year repeat revascularization rates by race and stent type

Figure 2.

Two year death/myocardial infarction rates by race and stent type

Among those that received DES, stent thrombosis rate was higher in blacks than whites, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (1.93% vs. 0.10%, p=0.09). In further subgroup analyses of patients that received DES (Table 5), Paclitaxel DES had better combined safety outcome (Death/MI) compared with BMS in blacks (14.55 vs. 24.11, P=0.04) and whites (10.20 vs. 14.63, P=0.018). Similarly, Sirolimus DES was associated with better safety outcome compared with BMS in blacks (12.98 vs. 24.11, p=0.003) and whites (11.17 vs. 14.63, p=0.034).

Table 5.

Cumulative Events Rates for Two Year Follow-up Stratified by Drug Eluting Stent Type

| Paclitaxel Follow-up Events | black-BMS (N=175) | black-Paclitaxel (N=182) | white-BMS (N=662) | white-Paclitaxel (N=637) | p_value White-BMS vs Paclitaxel |

p_value Black-BMS vs Paclitaxel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | |||

| Death | 15.18 | 9.51 | 8.86 | 7.21 | 0.24 | 0.13 |

| Death/MI | 24.11 | 14.55 | 14.63 | 10.20 | 0.018 | 0.04 |

| Repeat Revascularization | 22.59 | 12.03 | 21.03 | 13.95 | 0.0007 | 0.016 |

| Sirolimus Follow-up Events | black-BMS (N=175) | black-Sirolimus (N=349) | white-BMS (N=662) | white-Sirolimus (N=1242) | p_value White-BMS vs Sirolimus |

p_value Black-BMS vs Sirolimus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | |||

| Death | 15.18 | 7.73 | 8.86 | 6.07 | 0.02 | 0.013 |

| Death/MI | 24.11 | 12.98 | 14.63 | 11.17 | 0.034 | 0.0032 |

| Repeat Revascularization | 22.59 | 15.22 | 21.03 | 16.60 | 0.0095 | 0.055 |

BMS indicates bare metal stent; DES, drug eluting stent; MI, myocardial infarction. Cumulative event rates were calculated via the Kaplan-Meier method. The events are censored at 731 days.

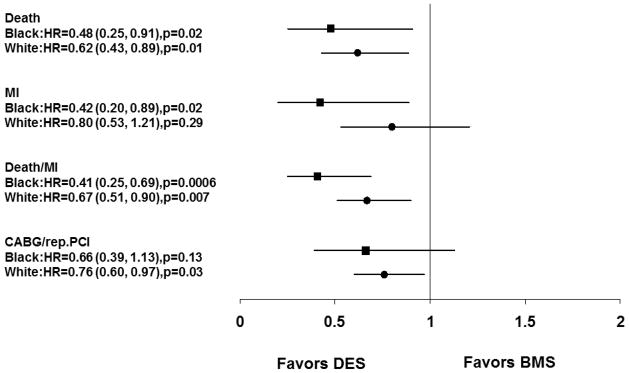

Figure 3 depicts propensity score-adjusted risks for adverse outcomes by 2 years for blacks and whites with DES versus BMS. Overall, the use of DES was associated with superior safety outcomes in both blacks and whites. In blacks, DES use was associated with an estimated 59% lower risk of death or MI (adjusted HR=0.41, 95% confidence interval 0.25–0.69, p<0.001), but only showed a nominal decrease with a 34% lower risk for repeat revascularization (adjusted HR=0.66, 95% confidence interval 0.39–1.13, p=0.13). For whites, the use of DES was associated with an estimated 33% lower risk of death or MI (adjusted HR=0.67, 95% confidence interval 0.51–0.90, p<0.007), and a 24% lower risk for repeat revascularization (adjusted HR=0.76, 95% confidence interval 0.60–0.97, p=0.03).

Figure 3.

Propensity adjusted relative benefit of drug eluting stent over bare metal stent at two years by race

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is that DES more effectively reduced death or MI by 2 years in both black and white patients, compared to BMS. This finding is particularly important given the considerable concern from recent reports questioning the safety of DES among blacks as a result of increased stent thrombosis8,9 and MI9 rates in blacks compared to other racial groups. As DES has become the standard of care in PCI, our study adds significantly to the body of literature that describes racial disparities in outcomes following PCI. Our study extends upon the findings of prior studies by demonstrating that DES use has superior safety profile across racial groups. Overall, the use of DES was associated with a reduction in the need for repeat revascularization. However, the reduction in the need for repeat revascularization was attenuated in blacks after statistical adjustment, likely related to relatively smaller sample of blacks in this analysis.

The results of the present study, which is based on a large, multi-center registry in the United States of real-word patients undergoing PCI, provide further evidence of the beneficial effects of DES. With follow-up of 2 years, a robust and sustained decrease in safety and efficacy outcomes were noted with use of DES in both blacks and whites. These benefits are particularly noteworthy given the differences in baseline characteristics between the groups. Compared to BMS-treated patients, those that received DES presented with a higher prevalence of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, renal insufficiency, and a longer mean lesion length. In spite of the fact that these characteristics portend worse outcomes, DES was found to be beneficial over BMS in blacks and whites. Our findings are consistent with recent report of analyses of data from National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Payer Databases indicating that use of DES was associated with better 30-month survival and lower rate of MI compared with BMS use among blacks, Asians and whites.15

This finding may represent a real phenomenon in that there are several reports of restenosis resulting in a higher rate of mortality.16, 17 Therefore, it is plausible that DES, by prevention of restenosis, may be associated with lower rates of death or MI. Still, our results should be interpreted with caution because there were important baseline differences between the BMS-treated and DES-treated groups within this population. The BMS-treated patients were more likely to present with unstable angina and with angiographic evidence for thrombus, both characteristics that may predispose them to worse clinical outcomes. Furthermore, despite our efforts to adjust statistically for baseline imbalances, it is still possible that there are unmeasured confounders that may partially explain some of these findings.

Several initial randomized trials and meta-analyses have shown that among patients without acute coronary syndromes, DES implantation is associated with a significant reduction in restenosis and need for repeat revascularization.1–4,18,19 However, concerns emerged regarding a higher risk of late stent thrombosis6–9,20,21 and MI9 associated with DES implantation, particularly in black patients.8,9 A single center study involving 7,236 patients (22% black) observed that black race, clopidogrel cessation, history of diabetes mellitus, history of congestive heart failure, and previous PCI were independent predictors of early stent thrombosis.8 In that study, black race also emerged as the strongest independent predictor of late stent thrombosis on multivariate analysis. In a similar fashion, Batchelor and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of pooled data from the TAXUS IV and V trials and the ATLAS clinical trials.9 Five-year clinical outcomes in 127 blacks, 169 asians, and 2,301 whites who received paclitaxel-eluting stents were compared. Despite higher antiplatelet compliance, the adjusted 5-year risks of MI and stent thrombosis were higher in blacks than whites.9 Consistent with these reports, we observed a numerically higher incidence of definite stent thrombosis rate, and death or MI among blacks compared to whites treated with DES. Although the pathophysiology of higher incidence of late stent thrombosis and MI with DES in blacks is not completely understood, it may relate to baseline characteristics and higher incidence of cardiovascular risk burden in blacks compared to whites. There are suggestions that poor socio-economic status, non-compliance with dual antiplatelet therapy, and genetic predisposition to clopidogrel resistance may contribute to this phenomenon.

The types of DES used in this study were the sirolimus and paclitaxel DES. Of note, paclitaxel and sirolimus DES stent types were associated with lower rates of death and MI, compared to BMS, in both blacks and whites in our studies. In contrast to prior studies,8, 9 we observed lower incidences of stent thrombosis. This difference may be related to differences in patients and lesions characteristics, duration of follow-up, definition of stent thrombosis, and method of capturing stent thrombosis events. With the introduction of newer-generation DES (Zotarolimus and Everolimus) with thinner, fracture-resistant struts, and biocompatible polymers, there are indications that rates of stent thrombosis have decreased,22 especially coupled with the benefits from more potent and/or prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy. However, racial differences in long term safety and efficacy outcomes with these newer generation stents also remain to be determined.

Several studies have documented existence of racial disparities in the use of invasive cardiac procedures including cardiac catheterization, PCI and CABG.23–25 Additionally, following the approval of DES by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2003, earlier observations indicated that blacks were less likely to receive DES during PCI.26,27 Although analysis of NCDR CathPCI registry indicated that DES use was similar across racial groups in 2005, followed by similar trends in use through 2008.15 In a study involving 418 hospitals with 430,509 patients with Medicare, 238,956 with private insurance, and 74,926 patients who were uninsured/Medicaid, admitted for MI showed that blacks and Hispanics were significantly less likely to receive in-hospital revascularization among the Medicare cohort, privately insured cohort, and uninsured/Medicaid cohort.28 Of note, with adjustment for baseline characteristics, blacks were approximately 25% less likely and Hispanics 5% less likely to receive revascularization as compared to whites with similar insurance.28 These observations indicate that insurance barriers and differences in baseline characteristics may not fully explain the prevailing racial and ethnic disparities in receipt of coronary revascularization procedures. The findings of the present study support preferential use of DES over BMS across racial groups.

Limitations

The Dynamic Registry is not a randomized trial. The number of blacks and BMS-treated patients compared to whites and DES-treated patients were relatively modest; nonetheless, we were able to identify significant differences. Despite performing multivariable analyses and propensity score adjustments, some residual confounders may still not be fully accounted; however, the large cohort of patients and the relatively higher baseline comorbid conditions among DES groups compared to BMS groups, argue in favor of the validity of our finding of improved outcome with DES use. Elimination of these baseline differences could potentially lead to even more marked outcome differences in favor of DES use. Of note, data on insurance and socio-economic status were not obtained and these may represent part of unmeasured confounders. Another limitation is that we may not be able to account for the precise effect of changing patterns in pharmacologic therapy of atherosclerosis and stent technology in terms of later years having both BMS and DES (waves 4 and 5) as well as more contemporary antiplatelet/antithrombotic agent. Furthermore, NHLBI dynamic registry did not include information on dual antiplatelet therapy compliance or blood testing for clopidogrel resistance. Despite these limitations, our results regarding rates of death and MI among DES and BMS treated patients mimic those from prior studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results show the benefits of DES over BMS in all patients regardless of race. Use of DES in PCI was associated with better long-term safety outcomes across racial groups. Compared to BMS, DES was more effective in reducing repeat revascularization in whites and blacks, but this benefit was attenuated after statistical adjustment in blacks. These findings support preferential use of DES over BMS in all patients regardless of race. Further studies are needed to determine the long term outcomes across racial groups with newer generation stents.

Highlights.

Use of DES in PCI was associated with lower rates of death or MI in blacks and whites in the NHLBI Registry at 2 years.

DES use was also associated with lower rate of repeat revascularization in blacks and whites.

Benefit of DES on repeat revascularization remained significant in whites but attenuated in blacks after adjustment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grant numbers HL033292 and 5K12HL109068-04).

Footnotes

Statement of Authorship: These authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.

Disclosures: All authors have no disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, Fitzgerald PJ, Holmes DR, O’Shaughnessy C, Caputo RP, Kereiakes DJ, Williams DO, Teirstein PS, Jaeger JL, Kuntz RE SIRIUS Investigators. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1315–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cox DA, Hermiller J, O’Shaughnessy C, Mann JT, Turco M, Caputo R, Bergin P, Greenberg J, Popma JJ, Russell ME TAXUS-IV Investigators. One-year clinical results with the slow-release, polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting Taxus stent: the TAXUS-IV trial. Circulation. 2004;109:1942–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127110.49192.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, Fajadet J, Ban Hayashi E, Perin M, Colombo A, Schuler G, Barragan P, Guagliumi G, Molnàr F, Falotico R RAVEL Study Group. Randomized Study with the Sirolimus-Coated Bx Velocity Balloon-Expandable Stent in the Treatment of Patients with de Novo Native Coronary Artery Lesions. A randomized comparison of a sirolimus-eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1773–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenhalgh J, Hockenhull J, Rao N, Dundar Y, Dickson RC, Bagust A. Drug-eluting stents versus bare metal stents for angina or acute coronary syndromes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;5:CD004587. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004587.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirtane AJ, Gupta A, Iyengar S, Moses JW, Leon MB, Applegate R, Brodie B, Hannan E, Harjai K, Jensen LO, Park SJ, Perry R, Racz M, Saia F, Tu JV, Waksman R, Lansky AJ, Mehran R, Stone GW. Safety and efficacy of drug-eluting and bare metal stents: comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized trials and observational studies. Circulation. 2009;119:3198–3206. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.826479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bavry AA, Kumbhani DJ, Helton TJ, Borek PP, Mood GR, Bhatt DL. Late thrombosis of drug-eluting stents: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Am J Med. 2006;119:1056–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalesan B, Pilgrim T, Heinimann K, Räber L, Stefanini GG, Valgimigli M, da Costa BR, Mach F, Lüscher TF, Meier B, Windecker S, Jüni P. Comparison of drug-eluting stents with bare metal stents in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:977–87. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins SD, Torguson R, Gaglia MA, Jr, Lemesle G, Syed AI, Ben-Dor I, Li Y, Maluenda G, Kaneshige K, Xue Z, Kent KM, Pichard AD, Suddath WO, Satler LF, Waksman R. Does black ethnicity influence the development of stent thrombosis in the drug-eluting stent era? Circulation. 2010;122:1085–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.907998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batchelor WB, Ellis SG, Ormiston JA, Stone GW, Joshi AA, Wang H, Underwood PL. Racial Differences in Long-Term Outcomes after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with Paclitaxel-Eluting Coronary Stents. J Interv Cardiol. 2013;26:49–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2012.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minutello RM, Chou ET, Hong MK, Wong SC. Impact of race and ethnicity on inhospital outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention (report from the 2000–2001 New York State Angioplasty Registry) Am Heart J. 2006;151:164–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen MS, Bhatt DL, Chew DP, Moliterno DJ, Ellis SG, Topol EJ. Outcomes in African-Americans and whites after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Med. 2005;118:1019–25. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leborgne L, Cheneau E, Wolfram R, Pinnow EE, Canos DA, Pichard AD, Suddath WO, Satler LF, Lindsay J, Waksman R. Comparison of baseline characteristics and one-year outcomes between African-Americans and Caucasians undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:389–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams DO, Holubkov R, Yeh W, Bourassa MG, Al-Bassam M, Block PC, Coady P, Cohen H, Cowley M, Dorros G, Faxon D, Holmes DR, Jacobs A, Kelsey SF, King SB, 3rd, Myler R, Slater J, Stanek V, Vlachos HA, Detre KM. Percutaneous coronary intervention in the current era compared with 1985–86; the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Registries. Circulation. 2000;102:2945–51. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.24.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marroquin OC, Selzer F, Mulukutla SR, Williams DO, Vlachos HA, Wilensky RL, Tanguay JF, Holper EM, Abbott JD, Lee JS, Smith C, Anderson WD, Kelsey SF, Kip KE. A comparison of bare-metal and drug-eluting stents for off-label indications. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:342–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar RS, Douglas PS, Peterson ED, Anstrom KJ, Dai D, Brennan JM, Hui PY, Booth ME, Messenger JC, Shaw RE. Effect of race and ethnicity on outcomes with drug-eluting and bare metal stents: results in 423 965 patients in the linked National Cardiovascular Data Registry and centers for Medicare & Medicaid services payer databases. Circulation. 2013;127:1395–403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen YL, Chen MC, Wu CJ, Yip HK, Fang CY, Hsieh YK, Chen CJ, Yang CH, Chang HW. Impact of 6-month angiographic restenosis inside bare-metal stents on long-term clinical outcome in patients with coronary artery disease. Int Heart J. 2007;48:443–54. doi: 10.1536/ihj.48.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schühlen H, Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Hausleiter J, Pache J, Dirschinger J, Schömig A. Restenosis detected by routine angiographic follow-up and late mortality after coronary stent placement. Am Heart J. 2004;147:317–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ardissino D, Cavallini C, Bramucci E, Indolfi C, Marzocchi A, Manari A, Angeloni G, Carosio G, Bonizzoni E, Colusso S, Repetto M, Merlini PA SES-SMART Investigators. Sirolimus-eluting vs uncoated stents for prevention of restenosis in small coronary arteries: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292:2727–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.22.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roiron C, Sanchez P, Bouzamondo A, Lechat P, Montalescot G. Drug eluting stents: an updated meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Heart. 2006;92:641–9. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.061622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFadden EP, Stabile E, Regar E, Cheneau E, Ong AT, Kinnaird T, Suddath WO, Weissman NJ, Torguson R, Kent KM, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Waksman R, Serruys PW. Late thrombosis in drug-eluting coronary stents after discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy. Lancet. 2004;364:1519–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, Ge L, Sangiorgi GM, Stankovic G, Airoldi F, Chieffo A, Montorfano M, Carlino M, Michev I, Corvaja N, Briguori C, Gerckens U, Grube E, Colombo A. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA. 2005;293:2126–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Philip F1, Agarwal S, Bunte MC, Goel SS, Tuzcu EM, Ellis S, Kapadia SR. Stent Thrombosis With Second-Generation Drug-Eluting Stents Compared With Bare-Metal Stents: Network Meta-Analysis of Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Trials in ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infraction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014 Feb;7(1):49–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.113.000412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whittle J, Conigliaro J, Good CB, Lofgren RP. Racial differences in the use of invasive cardiovascular procedures in the department of the veterans affairs medical system. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:621–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308263290907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kressin N, Petersen L. Racial differences in the use of invasive cardiovascular procedures: review of the literature and prescription for future research. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:352–66. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-5-200109040-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson ED, Shaw LK, DeLong ER, Pryor DB, Califf RM, Mark DB. Racial variation in the use of coronary-revascularization procedures. Are the differences real? Do they matter? N Engl J Med. 1997;336:480–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702133360706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hannan EL, Racz M, Walford G, Clark LT, Holmes DR, King SB, 3rd, Sharma S. Differences in utilization of drug-eluting stents by race and payer. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:1192–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao SV1, Shaw RE, Brindis RG, Klein LW, Weintraub WS, Krone RJ, Peterson ED. Patterns and outcomes of drug-eluting coronary stent use in clinical practice. Am Heart J. 2006;152:321–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cram P, Bayman L, Popescu I, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS. Racial disparities in revascularization rates among patients with similar insurance coverage. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:1132–9. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]