Abstract

Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)4 and CDK6 are frequently overexpressed or hyperactivated in human cancers. Targeting CDK4/CDK6 in combination with cytotoxic killing therefore represents a rational approach to cancer therapy. By selective inhibition of CDK4/CDK6 with PD 0332991, which leads to early G1 arrest and synchronous S phase entry upon release of the G1 block, we have developed a novel strategy to prime acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells for cytotoxic killing by cytarabine (Ara-C). This sensitization is achieved in part through enrichment of S-phase cells, which maximizes the AML populations for Ara-C incorporation into replicating DNA to elicit DNA damage. Moreover, PD 0332991 trigged apoptosis of AML cells through inhibition of the homeobox (HOX)A9 oncogene expression, reducing the transcription of its target PIM1. Reduced PIM1 synthesis attenuates PIM1-mediated phosphorylation of the pro-apoptotic BAD and activates BAD-dependent apoptosis. In vivo, timely inhibition of CDK4/CDK6 by PD 0332991 and release profoundly suppresses tumor growth in response to reduced doses of Ara-C in a xenograft AML model. Collectively, these data suggest selective and reversible inhibition of CDK4/CDK6 as an effective means to enhance Ara-C killing of AML cells at reduced doses, which has implications for the treatment of elderly AML patients who are unable to tolerate high dose Ara-C therapy.

Keywords: acute myeloid leukemia, pabociclib, Ara-C, HOXA9, synchronization

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common acute leukemia in adults, with the median age of 69 years old (1). Among genes that are implicated in the leukemogenesis of AML, high HOX gene expression has been associated with unfavorable prognosis, and lower HOXA9 expression correlates with a more favorable progression-free survival and response to therapy (2–4). However, despite intensive investigation of the etiology of AML and recent advances in targeted therapy, the nucleoside analog cytarabine (Ara-C) remains the first-line chemotherapy drug for AML for the last forty years. Unfortunately, older patients are generally intolerant to high dose Ara-C due to high toxicity, and have few alternative treatment options, thus resulting in dismal prognosis (5).

Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)4 and CDK6 are rarely mutated but frequently overexpressed or hyperactivated in human cancers (6,7). PD 0332991 (palbociclib), a cell permeable pyridopyrimidine with oral bioavailability, is an exceptionally selective and potent inhibitor of CDK4 and CDK6 (IC50~10 nM for recombinant proteins) (8). Unlike other CDK inhibitors, at concentrations specific for inhibition of CDK4/CDK6, PD 0332991 has little or no activity against at least 38 additional kinases, including CDK2 due to steric hindrance (8). Providing the first evidence for PD 0332991’s bioactivity in primary cancer cells, we showed that PD 0332991 inhibited CDK4/CDK6 in primary human multiple myeloma cells (IC50, 60 nM) in the presence of bone marrow stromal cells, leading to early G1 arrest (9). PD 0332991 was similarly effective in inhibiting CDK4/CDK6 in AML, mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), glioblastoma and many other cancer types ex vivo (10–12), and suppressed tumor growth in myeloma, MCL and AML tumor xenografts (8,9,11) and in an immune competent mouse myeloma model (13).

Induction of early G1 arrest by PD 0332991 requires retinoblastoma (Rb), the substrate of CDK4 and CDK6, but not p53, and this is reversible in vitro and in vivo (14). In the first–in-human single agent phase I clinical trial, PD 0332991 effectively inhibited CDK4/6 and induced early G1 arrest within tolerable doses, resulting in a favorable clinical response in relapse/refractory MCL patients (15). When used in combination with letrozole, PD 0332991 more than tripled the progression-free survival of metastatic breast cancer patients treated with letrozole alone in a phase 2 clinical trial (16). The selectivity and reversibility of cell cycle inhibition by PD 0332991 and its clinical efficacy suggest a unique opportunity to target specific phases of the cell cycle in cancer.

To advance mechanism-based targeting of CDK4/CDK6 in AML, we now show that induction of early G1 arrest by PD 0332991 inhibition of CDK4/CDK6 resulted in efficient synchronization of AML cells. Following release of PD 0332991-induced early G1 arrest, AML cells progress synchronously into S phase, thereby creating a defined time window during which AML cells are poised for incorporation of Ara-C. Moreover, sequential PD 0332991 + Ara-C treatment resulted in a dramatic increase in cytotoxic killing of AML cells in vivo. At the molecular level, induction of early G1 arrest by PD 0332991 led to reduced expression of HOXA9 and the HOXA9-target gene Pim1. This resulted in a loss of inhibitory phosphorylation of BAD, and subsequent activation of BAD-mediated apoptosis in response to Ara-C. Our results suggest that the anti-tumor activity of PD 0332991 stems from both reversible G1 arrest that sensitizes AML cells to Ara-C-based therapy, and effective downregulation of HOXA9 expression that leads to the de-repression of a pro-apoptotic response.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

The human AML cell line HL-60 and the U937 histiocytic lymphoma with monocytic features were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cell lines were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 units/mL streptomycin. The human primary CD34+ AML cells were purified using MACS CD34 MicroBeads (Miltenyl Biotec), and co-cultured with mitomycin-treated HS-5 human stromal cells (17). The peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated using ficoll density centrifugation (GE lifetechology). Cytarabine (Ara-C) was purchased from Sigma. PD 0332991 was obtained from Pfizer (La Jolla, CA).

Cell cycle analysis

HL-60 cells were incubated with PD 0332991, or phosphate buffered saline (PBS; vehicle control) for the indicated periods of time. 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU, 5 µg/ml) (Sigma) was added to AML cells for 30 minutes and centrifuged. The cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and fixed in 70% ethanol. BrdU uptake was measured by flow cytometry as described (17,18), using a FITC-anti-BrdUrd (Roche Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA) monoclonal antibody. Subsequently, cells were stained with 0.05 mg/mL propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.1% RNase (Invitrogen) for 30 minutes at room temperature, and subjected to analysis by flow cytometry.

Western blot

HL-60 cells (1.0 × 106) were lysed in 0.5 mL of modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN)). The lysates were boiled in Laemmli sample buffer, and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane, blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 0.1% Tween 20, and 5% bovine serum albumin, and probed with a primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the blot was washed with PBS and 0.1% Tween 20, and specific antibody binding was detected with a horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody, followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, United Kingdom) and exposure to film.

For immunoblotting, the following antibodies were used: β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), RB, phospho-RB (Ser 807/811), BAD, HOXA9, (Cell Signaling, Beverly, CA).

Cell apoptosis and viability

Apoptotic and dead cells were analyzed by staining the cells with MitoTracker Red CMXRos (33 nM) (Invitrogen) to detect mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. Live cells were determined by trypan blue exclusion in triplicate.

Quantitative Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). The first strand cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng of total RNA using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). cDNA products were quantitated using the SYBR green fluorescence reagent on the ABI PRISM 7900 HT Sequence Detection System. Cycle threshold results were normalized to β-actin gene expression.

Establishment of myeloid leukemia xenografts and therapy

A total of 500 HL-60 cells stably expressing the HSV-TK-eGFP-luciferase fusion protein were injected via the lateral tail vein into NOD/SCI/IL-2Rγ mice. The tumor distribution was followed by serial whole-body noninvasive imaging of visible light emitted by luciferase-expressing HL-60 cells upon injection of mice with luciferin. Seven days after tumor injection, the NOD/SCID/IL-2Rγ mice with established myeloid leukemia were divided into four groups. PD 0332991 was dissolved in vehicle (50 mM sodium lactate, pH 4.0) and was given daily by gavage at 150 mg/kg for days indicated. Ara-C (1.6 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally (i. p.) as indicated. The control mice received the vehicle through the same route and on the same schedule. Survival times were compared with Kaplan-Meier survival analysis.

Ectopic expression of human HOXA9

To express human HOXA9, the HOXA9 retroviruses were produced by cotransfecting 293T cells with the PINCO-HOXA9 plasmid and the pAmpho and pQE plasmids (19). The PINCO retroviral vector was used as the control retrovirus. HL-60 cells were spin-infected with viral supernatants at 2,000 rpm for 2 hour at room temperature.

shRNA knockdown

To knockdown BAD, the pKLO.1 vector carrying BAD or the GFP control shRNA (Sigma) was co-transfected with pVSVG and Delta-8.9 plasmids into 293T cells to generate the desired shRNA lentivirus (17). Knockdown of each target was validated by quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblotting at 72 h post-transduction.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis of the in vitro data, the Student’s t-test was used. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to determine the effect of treatment on the survival of the mice.

Results

Cell cycle synchronization of AML cells by PD 0332991

Ara-C is a deoxynucleoside analog that is incorporated into replicating DNA only during the S phase of the cell cycle. We posit that strategies to enrich asynchronously growing AML cells in S phase will maximize the AML population poised for Ara-C incorporation, thereby increasing the efficiency of cytotoxic killing at a reduced Ara-C dose. To this end, PD 0332991 has been shown to be a selective and potent inhibitor for CDK4 and CDK6 in vitro and in vivo in animal models, and in a clinical trial of recurrent MCL (9–13,15). We first assessed the impact of PD 0332991-dependent cell cycle inhibition on enhancement of Ara-C cytotoxicity in fresh primary AML patient cells. These fresh CD34+ AML cells were still engaging in active cell cycle, as determined by BrdU uptake by flow cytometry (Fig. S1). These patient CD34+ AML cells were first treated with 0.5 µM or 1 µM PD 0332991 for 24 hours, followed by wash off and culturing for 24 hours to allow synchronized S phase entry. 5 µM Ara-C was administered and cell viability determined by trypan blue staining 24 hours post Ara-C. As shown in Fig. 1A, pre-treatment with PD 0332991 for 24 hours resulted in induction of cell death in approximately 50% of primary AML cells following Ara-C administration. In comparison, only 17% AML cells lost viability without cell cycle synchronization when PD 0332991 and Ara-C were simultaneous administrated (Fig. 1A, left panel).

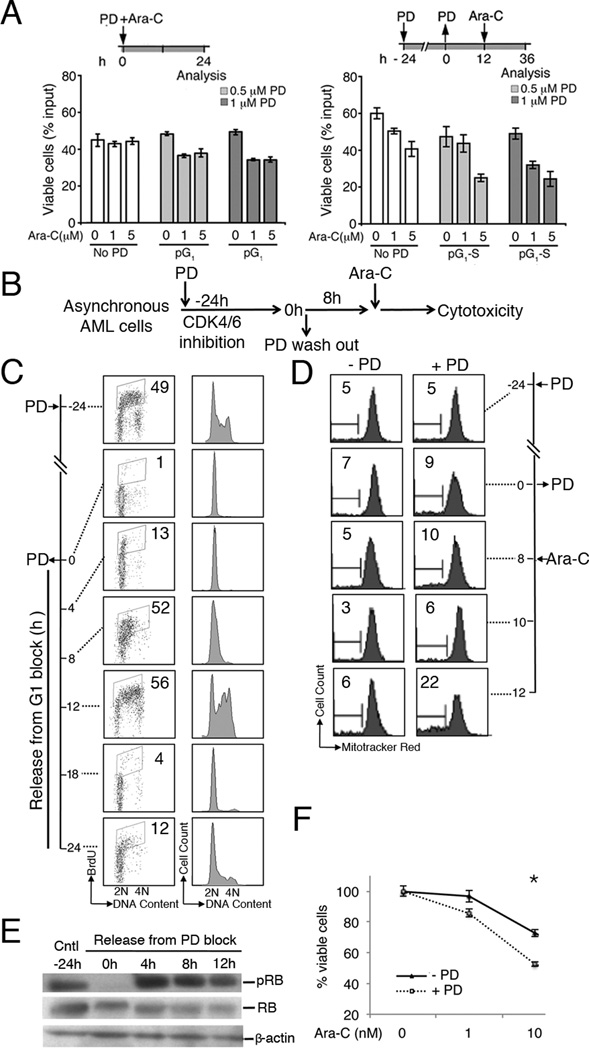

Fig 1. PD 0332991 synchronization enhanced cytotoxic killing of HL-60 promyelocytic leukemia cells by Ara-C.

A. Human purified CD34+ cell from AML patient were cultured with mitomycin treated HS-5 human stromal cells. In left pannel primary AML cells co-treated with PD 0332991 (0, 0.5 and 1 µM) and Ara-C (0, 1 and 5 µM) for 24 hours and cell viability was determined by trypan blue staining. In right panel the same AML cells were treated with PD 0332991 (0, 0.5 and 1 µM) for 24 h to induce G1 arrest and then cultured in fresh medium for 12 h to allow re-entry into S-phase before the addition of Ara-C (0, 1 and 5 µM). Cell viability was determined by trypan blue staining after Ara-C 24 hours treatment. B. Schematic diagram of the protocol for cell cycle synchronization by reversible PD 0332991 arrest in G1 and subsequent cytotoxic killing by Ara-C upon release into S phase. C. HL-60 cells were cultured in 0.5 µM PD 0332991 for 24 hours, then released into fresh media and harvested at the indicated time points. BrdU was added at each time point indicated for 30 min, followed by propidium iodide (PI) staining and FACS analysis of BrdU uptake (left panel) and DNA content (right panel). Numbers indicate the percentages of BrdU-positive S phase cells. D. HL-60 cells were arrested by 0.5 µM PD 0332991 and released into fresh medium. Ara-C (50 nM) was added at 8 hr after PD 0332991 removal, and apoptosis induction measured by loss of mitochondrial membrane potential using the Mito Tracker Red CMXRos assay (Invitrogen). The time course of PD 0332991 arrest, release and Ara-C administration were indicated on the right. Numbers indicate the percentages of MT-negative cells. E. Inhibition of CDK4/6-dependent Rb phosphorylation on serine 807/811 (pRb) as an indication of induction of early G1 arrest 24 hours post PD 0332991. Release of PD 0332991 arrest and S phase entry was marked by re-phosphorylation Rb. pRb and overall Rb levels were detected by Immunoblotting at the indicated time points by the anti-phospho-Rb and anti-Rb antibodies (Cell Signaling). β-actin was also measured as the loading control. F. HL-60 cells were arrested in early G1 by PD 0332991 for 24 hrs and released synchronously into S-phase for 8 hours. Ara-C was added at the indicated doses for 48 hours, and cell viability was determined by trypan blue staining. These data are representative of 3 independent experiments; error bars indicate standard deviation. * Statistical significance, P < 0.05.

On this basis, we investigated the mechanisms by which sequential PD 0332991 and Ara-C administration enhances cytotoxic killing of AML cells using AML cell lines that are more readily available and amenable to genetic interrogations. We posit that induction of early G1 arrest by PD 0332991 followed by synchronous S-phase entry upon release of the G1 block would allow more AML cells to incorporate Ara-C than those of asynchroneously growing cells, thereby enhancing the efficiency of cytotoxic killing (Fig. 1B). The human HL-60 AML cells were cultured in the presence of 0.5 µM PD 0332991 or the DMSO vehicle. PD 0332991 completely inhibited CDK4/CDK6 within 24 hours, as indicated by the loss of CDK4/CDK6-specific phosphorylation of Rb on serine 807–811 (pRb), arrested the cell cycle in G1, and marked reduction of DNA replication as measured by BrdU pulse-labeling (Fig. 1C, 1E). Following wash out of PD 0332991 from the medium, HL-60 cells began to enter S phase by 4 hours, with concomitant increase in pRb. By 8 hours, the majority of HL-60 cells were progressing into S phase (Fig. 1C and 1E). Similar results were obtained in the U937 histiocytic lymphoma with acute monocytic leukemia morphology in response to PD 0332991 treatment and release (Fig. S2). Thus PD 0332991 effectively arrested AML cells in early G1, and synchronized them in S phase after PD 0332991 withdrawal.

Cell cycle synchronization by PD 0332991 enhances Ara-C killing of AML cells

Ara-C is converted to cytosine arabinoside triphosphate by deoxycytidine kinase (dCK), and to a lesser extent, by deoxyguanosine kinase, which elicits cytotoxicity when incorporated into replicating DNA in S phase through termination of DNA strand elongation (20,21). To determine if S phase synchronization sensitizes AML cells to Ara-C, HL-60 cells were arrested in G1 by PD 0332991, and then released to fresh medium to allow synchronized entry into S phase. Ara-C was administered at 8 hours after removal of PD 0332991 when maximal S phase enrichment was achieved, and induction of apoptotic cell death was determined by the MitoTracker assay that measures the permeabilization of mitochondrial outer membrane. The asynchronously growing HL-60 cells were similarly treated with Ara-C as a control. By 4 hours of Ara-C treatment, 22.3% of S phase-synchronized HL-60 cells underwent apoptosis --- a 3.5-fold increase in apoptotic cells was determined over the asynchronous cells (6.4%) (Fig. 1D). Similar enhancement of apoptosis upon PD 0332991 synchronization was observed in U937 cells in response to Ara-C (Fig. S2). This led to a further 20% reduction of viability in the S phase- synchronized HL60 cells compared to that of the asynchronous HL60 cells at low dose (10 nM) Ara-C treatment (Fig. 1F). Together, these data indicate that S phase synchronization upon PD 0332991 arrest and release markedly enhances Ara-C-mediated cytotoxic killing of AML cells.

Reversible CDK4/CDK6 inhibition by PD 0332991 enhanced tumor suppression by Ara-C

We next evaluated the anti-tumor effect of sequential PD 0332991 and Ara-C administration in disseminated AML xenografts in NOD/SCID/IL-2Rγ (NSG) mice. Previously, we have shown that cell cycle synchronization in vivo can be achieved by timely administration of PD 0332991 that induced G1 arrest, followed by discontinuation of PD 0332991 to allow S phase entry (14).

In this AML xenograft model, a total of 500 HL-60 cells stably expressing the HSV-TK-eGFP-luciferase transgenes (HL-60-LUC+) were injected via tail vein into NSG mice (5 groups, 5 mice per group) for induction of disseminated tumors, which were monitored by serial noninvasive bioluminescence imaging (BLI). PD 0332991 (150 mg/kg) was administered daily by gavage on days -6 to -4 after tumor induction to arrest cell cycle in G1. After 4 days of PD 0332991 withdrawal, which we previously determined to achieve maximal S phase entry (14), Ara-C was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at low dose (1.6 mg/kg) or high dose (10 mg/kg) daily for 3 consecutive days. Tumor load was measured by BLI weekly between day 2 and day 23 (Fig. 2A). As a control, NSG mice with HL-60-LUC+ xenografts were treated with either PD 0332991 or Ara-C alone at low or high dose in parallel. Disseminated tumors developed by 14 days following the injection of HL-60-LUC+ cells (Fig. 2B–2C).

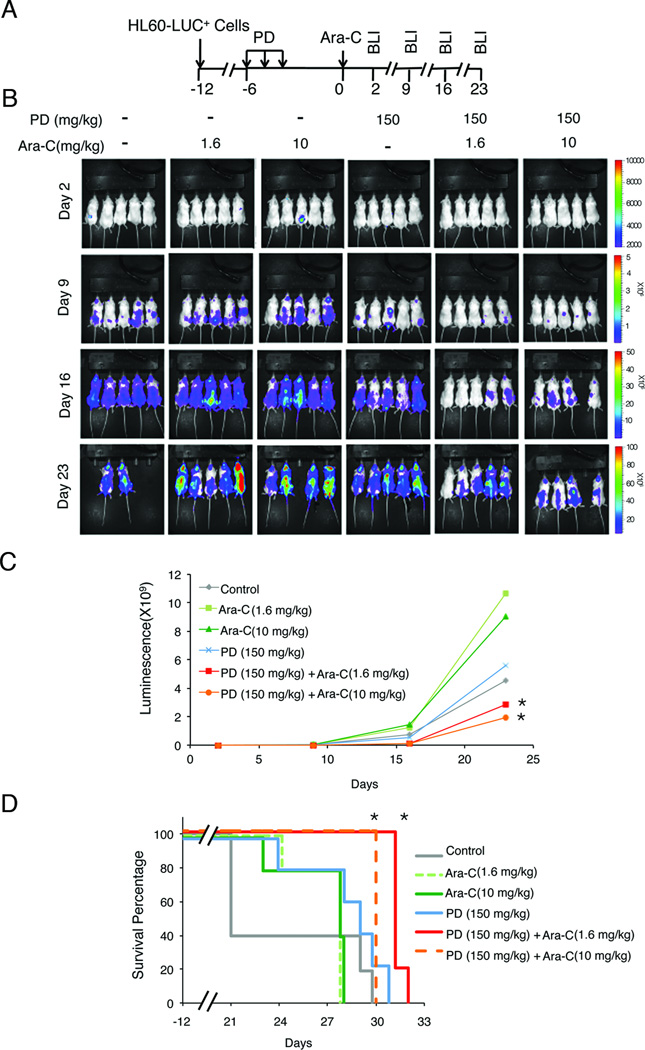

Fig. 2. PD 0332991 synchronization enhanced tumoricidal activity of Ara-C in HL-60 xenograft NOD/SCID/IL-2Rγ mice.

A. Schematic diagram for in vivo cell cycle synchronization by three consecutive PD 0332991 doses and one Ara-C administration for disseminated HL-60 xenograft tumors in NSG mice. B. PD 0332991 (150 mg/Kg) and Ara-C (1.6 mg/Kg or 10 mg/Kg) treatment of NSG mice developing aggressive xenograft tumor following injection with Luc+GFP+HL-60 cells, and the time (day) of bioluminescence imaging (BLI) analyses. C. Bioluminescence representing tumor mass (photons/s/cm2/ steradian) on days post injection of Luc+GFP+HL-60 cells indicated. Mean normalized values curve plotted for each treatment group. D. Kaplan-Meier survival plots demonstrating survival benefit from PD 0332991 and Ara-C combination therapy. These data are representative of 5 animals/group. * Statistical significance, P < 0.05.

A single regimen of Ara-C at a low or high dose had little or only marginal effect on the tumor load, whereas PD 0332991 alone initially suppressed the tumor growth (Day 9), but was unable to sustain the inhibitory effect (Days 16–23). Strikingly, the sequential PD 0332991- Ara-C treatment marked reduced tumor load at all time points compared with the control groups (Fig. 2B). Notably, inhibition of tumor development by Ara-C at low dose (1.6 mg/kg) in PD 0332991-synchronized HL-60-LUC+ xenografts was 9-times greater on day 9 and 16-times greater on day 16 than in asynchronous HL-60-LUC+ xenografts (Fig. 2B–C). Although the PD 0332991-high Ara-C dose regimen decreased the tumor load further (Fig. 2B, compare the 3rd and 6th groups, Fig. 2C), mortality occurred, as did the single high dose Ara-C treatment, (Fig. 2D). In comparison, none of the mice treated with the combined PD 0332991- low dose Ara-C regimen succumbed to death while on therapy, demonstrating improved survival over other treatment groups (Fig. 2B–D). Together, these results indicate that PD 0332991 synchronization markedly enhances the killing of AML cells at a significantly reduced Ara-C dose that was otherwise ineffective.

Cell cycle-coupled regulation of HOXA9 expression mediates Ara-C killing

Dysregulation of the leukemogenic HOXA9 oncoprotein is frequently observed in AML and is associated with poor prognosis and therapy response (2–4). To elucidate the mechanisms that underlie cell cycle enhancement of Ara-C killing, we investigated the PD 0332991 response of HOXA9. In prolonged early G1 arrest induced by 24 hours of PD 0332991 treatment, there was a sharp decline of both the mRNA and protein levels of HOXA9 (Fig. 3A–B), which coincided with de-phosphorylation of RB (Fig. 1E). The HOXA9 mRNA levels began to recover at 8 hours after the release of the G1 block when the majority of HL-60 cells were entering S phase, peaked at 12 hours (S/G2), and declined as cells entered the next G1 phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 3A, compare with Fig. 1A)(Fig. 1E). The HOXA9 protein levels also began to recover at 8–12 hours after PD 0332991 removal in middle-late S phase, which paralleled that of HOXA9 mRNA (Fig. 3B). However, even with the HOXA9 mRNA levels declining sharply between 12 and 24 hours, the HOXA9 protein continued to increase in G2/M, reaching the pretreatment level as cells entered the next G1 phase of cell cycle (Fig. 3B and 1A). These data indicated that the expression of HOXA9 mRNA, but not protein, is coupled to the cell cycle: low in G1 and G1/S transition, elevated in S phase, and declined as the cells entered G2/M. The basis for the uncoupling of HOXA9 mRNA and protein expressed is currently unknown, but induction of prolonged early G1 arrest likely led to perturbation of translational, posttranslational modification or degradation pathways that governs the steady state levels of HOXA9 protein.

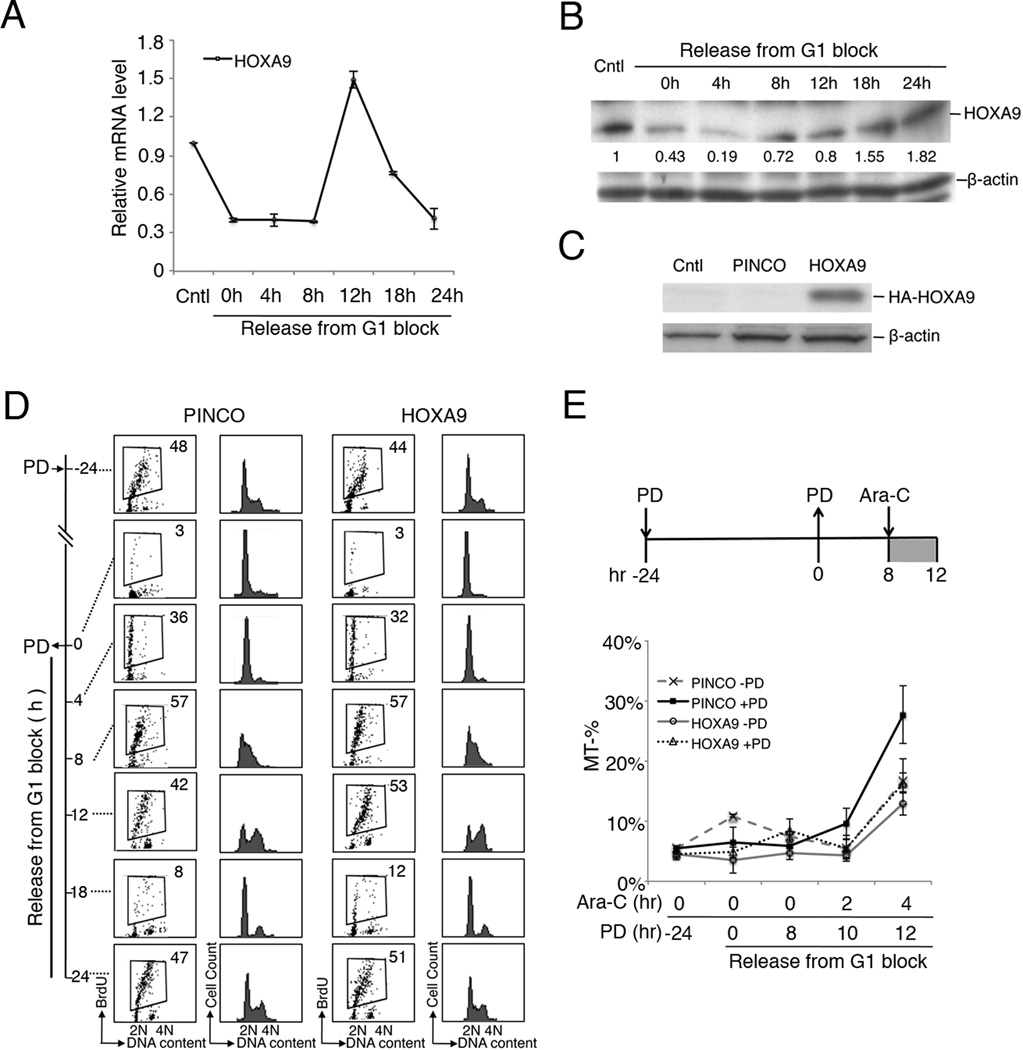

Fig. 3. HOXA9 is a cell cycle-regulated gene with lowest expression in S phase.

RT-qPCR (A) and immunoblotting (B) of HOXA9 expression during PD 0332991-induced G1 arrest and subsequent release of G1 block for resumption of cell cycle progression of HL-60 cells. Numbers below the HOXA9 blot in (B) represent levels of HOXA9 relative to that prior to PD 0332991 arrest. C. Immunoblotting to detect ectopic expression of HA-tagged HOXA9 from stable HL-60-HOXA9 cell line derived from PINCO-HA-HOXA9 retroviral infection. Cntl, mock infection; PINCO, infection with the control PINCO retrovirus. D. Enforced expression of HOXA9 did not affect cell cycle of HL-60 cells. HL-60 stably expressing HOXA9 or PINCO vector control cells were arrested by 1.0 µM PD 0332991 for 24 hours, released into fresh medium, and harvested at the indicated time points. BrdU was added at time indicated for 30 min for propidium iodide (PI) staining and FACS analysis of BrdU uptake (left panel) and DNA content (right panel). Numbers indicate the percentages of BrdU-positive S phase cells. E. Enforced HOXA9 expression in HL-60 cells conferred increased protection against cytotoxicity of PD 0332991+Ara-C combination treatment, as measured by the percentage of Mito Tracker-negative cells at the indicated time points. These data are representative of 2 independent experiments, and error bars indicate standard deviation.

This led us to investigate whether the PD 0332991-mediated uncoupling of HOXA9 protein expression in S phase contributes to enhanced Ara-C killing. HL-60 cells were infected with a recombinant PINCO-HOXA9 retrovirus to establish stable cell lines in which ectopic expression of HOXA9 did not fluctuate during the cell cycle (Fig. 3C). Despite the striking cell cycle-dependence of endogenous HOXA9 mRNA expression, and the ability of HOXA9 to stimulate proliferation of primitive hematopoietic cells (24–26), enforced expression of HOXA9 did not affect the kinetics of PD 0332991-dependent G1 cell cycle arrest or the subsequent S phase entry upon release of PD 0332991 (Fig. 3D).

HOXA9 is also known to have anti-apoptotic activity (22). We therefore posit that the reduction of HOXA9 protein levels by prior PD 0332991-induced G1 arrest may influence the survival of synchronized HL-60 cells in response to Ara-C. Indeed, enforced expression of HOXA9 dramatically inhibited Ara-C-induced apoptosis, as determined by the reduction of mitochondrial permeabilization in Ara-C-treated HL-60 cells, more pronounced in PD 0332991 synchronized cells than in the absence of PD 0332991 synchronization (Fig. 3E). These results are consistent with an anti-apoptotic role of HOXA9 (22). Importantly, they revealed that PD 0332991 synchronization not only amplifies the DNA damage by maximizing Ara-C incorporation into replicating DNA, but also compromises the anti-apoptotic capacity of HOXA9 by delaying the restoration of HOXA9 protein expression during S phase.

Reduced BAD expression conferred increased resistance to apoptosis induction by the PD 0332991-Ara-C combination therapy

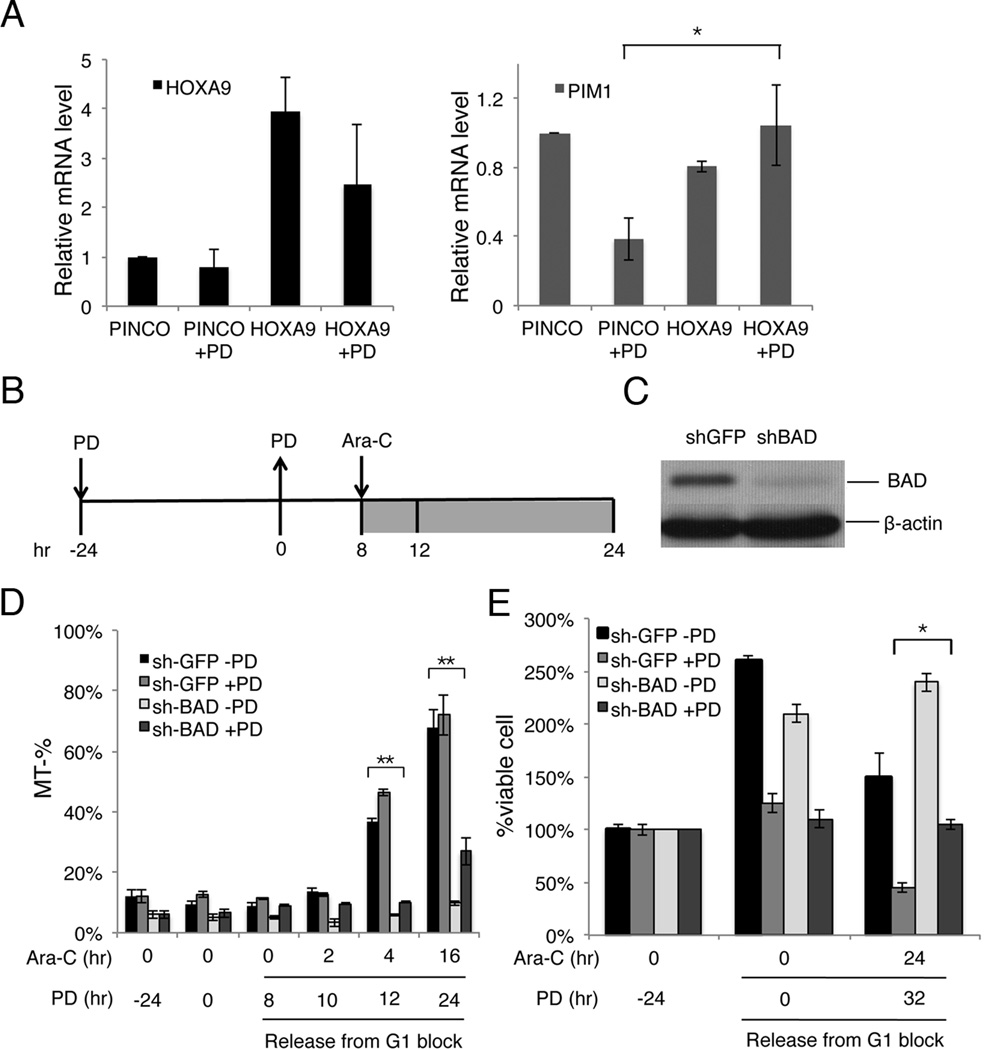

HOXA9 is a transcription factor that upregulates the expression of the Ser/Thr kinase Pim1, a direct transcriptional target (22). In turn, Pim1 phosphorylates the pro-apoptotic protein BAD on Serine112which inactivates BAD and attenuation BAD-mediated apoptosis (22). The PIM1 mRNA was reduced ~60%, in parallel with the reduction of HOXA9 mRNA and protein expression following prolonged early G1 arrest induced by PD 0332991 treatment for 24 hours (Fig. 4A). Ectopic expression of HOXA9 in HL-60 cells effectively prevented the reduction of PIM1 mRNA in PD 0332991-induced G1 arrested cells, consistant with PIM1 being a direct transcriptional target of HOXA9 (Fig. 4A) (22). Knocking down BAD expression by shRNA, markedly increased the resistance of HL-60 cells to apoptosis induced by the PD 0332991-Ara-C combination therapy (Fig. 4B–4E). Notably, the shGFP-expressing HL60 cells exhibited high basal level rates of apoptosis (15%) compared to the native HL60 cells (5%) under normal growth conditions (compare Figs. 4D and 1D),and the fold-increase of Ara-C-induced apoptosis was less pronounced upon exposure to Ara-C. Nevertheless, the survival of these PD 0332991-synchronized shGFP-HL60 cells was markedly reduced after Ara-C treatment. Together, these results provide compelling evidence that PD 0332991-induced sensitization of AML cells to Ara-C cytotoxicity is mediated, at least in part, by the reduction of HOXA9 and its transcriptional target PIM1, thereby enhancing the pro-apoptotic effect of BAD.

Fig. 4. PD 0332991-induced downregulation of the HOXA9-PIM1-Bad pathway contributes to the sensitization of AML cells to apoptotic induction and Ara-C cytotoxicity.

A. Enforced HOXA9 expression rescued the PD 0332991-induced decrease of endogenous HOXA9 and its transcriptional target PIM1. The mRNA levels of HOXA9 and PIM1 in HL-60-HOXA9 or control HL-60 cells were determined by RT-qPCR in the presence or absence of PD 0332991 treatment. B. Schematic diagram of the protocol for sequencial PD 0332991 and Ara-C administration. C. Immunoblotting to determine lentiviral shRNA-mediated silencing of BAD in stable HL-60 cells. D–E. Ara-C-induced apoptosis and cell death were measured by the Mito Tracker Red CMXRos assay (D) and trypan blue staining (E) in asynchronous or PD 0332991-sensitized control or BAD-knockdown HL-60 cells, respectively. These data are representative of 3 independent experiments; error bars indicate standard deviation. * Statistical significance, P < 0.05. * *Statistical significance, P < 0.01.

Discussion

The CDK4/CDK6-specific inhibitor PD 0332991(palbociclib) is under intense investigation for its clinical efficacy in cell cycle control and enhancing tumoricidal activity in combination therapy (9,12,14,15,27,28). This study took advantage of the reversibility of PD 0332991 inhibition of CDK4 and CDK6 to synchronize AML cells in S phase in order to maximize the percentage of AML cells poised for incorporating Ara-C into replicating DNA at a defined time point, thereby potentiating the tumoricidal activity of Ara-C. It is noteworthy that high-dose Ara-C in combination with anthracyclines remains the major induction chemotherapy for AML patients below 60 years of age (5). However, the median ages of the majority of AML patients at the time of diagnosis are typically between 65–70 years when they are less tolerant of the toxic effect of the intensive Ara-C regimen. As such, there is an urgent unmet need to develop novel therapies that effectively manage the leukemic disease for elderly AML patients.

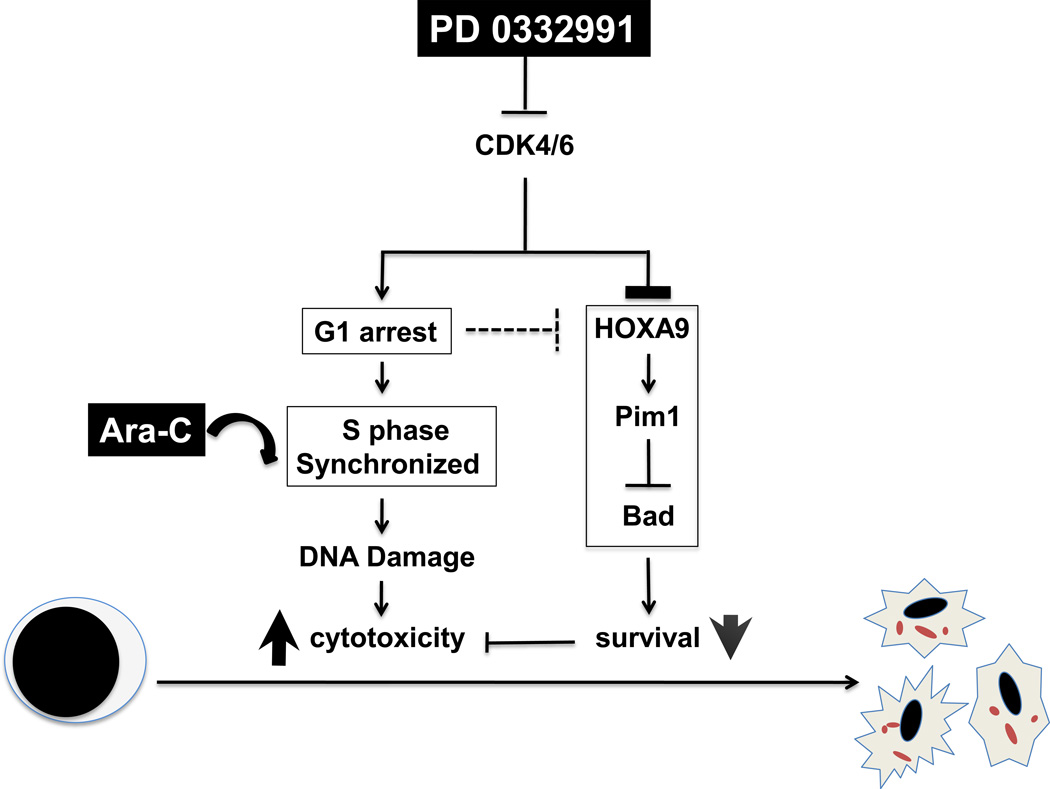

Our studies demonstrated that PD 0332991-mediated enrichment of AML cells at the S phase markedly enhances cytotoxic killing of AML cells at much reduced doses of Ara-C (Fig. 5). PD 0332991-synchronized HL-60 xenograft mice responded favorably to low dose Ara-C (1.6 mg/kg) in reducing tumor load and displayed overall improved survival (Fig. 2). The increased mortality in mice treated with high dose Ara-C (10 mg/kg), with or without PD 0332991 synchronization, further highlights the benefit of cell cycle synchronization by PD 0332991 that markedly enhanced the tumoricidal effect of Ara-C at significantly reduced doses. These findings implicate that cell cycle sensitization with PD 0332991 in combination with reduced dose of Ara-C may improve the treatment outcomes of AML patients who are otherwise ineligible to the current high dose Ara-C regimen.

Fig. 5. PD 0332991 sensitizes AML cells to Ara-C killing by at least two mechanisms.

(1) S phase synchronization for maximal Ara-C incorporation in replicating DNA, and (2) dismantling the HOXA9-dependent anti-apoptotic pathway.

Sensitization of AML cells to Ara-C by PD 0332991 treatment likely results from alterations of multiple cellular signaling pathways, such as the DNA damage response and survival pathways that are secondary to induction of prolonged early G1 arrest. First, induction of prolonged early G1 arrest and sensitization of cancer cells to cytotoxic killing by PD 0332991 is due to inhibition of CDK4/CDK6 as it absolutely requires Rb, the substrate of CDK4 and CDK6, and was recapitulated by silencing both CDK4 and CDK6 (14,28). Second, induction of prolonged early G1 by PD 0332991 sensitizes cancer cells to cytotoxic killing by a partner agent by forcing an imbalance in genes expression. In prolonged early G1 arrest that exceeds the early G1 transit time by PD 0332991 inhibition of CDK4/CDK6, only genes programmed for early G1, and not other cell cycle phase are expressed, and the cell cycle-coupled gene expression is incompletely restored upon release from the G1 block (14). Consistent with reprogramming of cancer cells for cytotoxic killing by induction of prolonged early G1 arrest, PD 0332991 treatment alone (for 21 days) resulted in tumor regression and durable complete and partial responses in some recurrent MCL patients in the first single agent phase I clinical trial (15).

At the mechanistic level, we observed a striking down-regulation of the leukemogenic HOXA9 oncogene as one such response of AML cells to PD 0332991 treatment. Our studies established HOXA9 as a cell cycle-coupled gene, with increased mRNA expression in S phase over other cell cycle phases. Surprisingly, while the HOXA9 protein level paralleled that of the mRNA level in G1 and S phase albeit with a delay, it did not follow the reduction of mRNA as cells exit S phase. It is possible that the prolonged early G1 arrest induced by PD 0332991 altered the translational efficiency of HOXA9 or the posttranslational modification pathways that rendered HOXA9 refractory to degradation post-S phase. Future studies will be required to determine the basis for the delay in restoration of HOXA9 protein in S phase synchronization following prolonged early G1 arrest. However, the delay in HOXA9 expression apparently contributes to cell cycle sensitization to Ara-C killing.

Suppression of HOXA9 expression led to concomitant reduction of expression of the HOXA9-target Pim1 gene, and the subsequent de-repression of phosphorylation of BAD, resulting in promotion of apoptosis. Indeed, enforced expression of HOXA9 restored Pim1 expression and attenuated the Ara-C-induced death of AML cells. Brumatti et al. recently reported that HOXA9 is also required to maintain the expression of BCL2, which is critical for the leukemogenic activity of HOXA9 in myeloid progenitors (23), although it is yet unclear whether HOXA9 acts directly on the transcription of BCL2, as seen with Pim1. HOXA9 appears essential for survival of HL60 cells, as silencing of HOXA9 by lentiviral shRNA led to massive cell death (Chen and Zhou, unpublished). This precludes a direct assessment of how reduced HOXA9 expression may affect Ara-C-induced cell death. It is noteworthy that HL-60 cells with enforced expression of HOXA9 were not fully refractory to Ara-C, and prolonged treatment of Ara-C resulted in loss of viability, suggesting that the combined PD 0332991-Ara-C therapy disabled other survival mechanism(s) required for drug resistance. Future genome-wide interrogations of cellular pathways such as RNAi knockdown or enforced expression of cDNA libraries in AML cells will likely discover these new cellular pathways and targets that aid the design of more effective therapeutic strategies for AML.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gail J. Roboz and Monica L. Guzman for primary AML cells, members of the Chen-Kiang and Zhou labs for helpful discussions, and Kang Zhang for technical assistance. This work was supported in part by an Investigator Initiated Research Project from Pfizer, the STARR Cancer Consortium grant #I3-A162 and NIH grant R01 CA 120531 to S.C.K., the Gar Reichman Fund of the Cancer Research Institute to M.A.S.M, and NIH grants 5R01 CA098210 and 1R01 CA159925 to P.Z.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Authorship

Contributions: C.Y. conducted research and analyzed data; C. A. B. conducted the AML xenograft studies and analyzed the data together with D. S. D.; M.D.L. and X.H. contributed to the design of in vitro and mouse experiment and optimization of the PD 0332991-Ara-C combination therapy; M.D.L. and C.Y. also conducted the combination treatment of primary AML cells. M.A.S.M. supervised the AML xenograft studies and edited the manuscript, S.C.K. and P.Z. designed the research, analyzed the data and provided the funding support. C.Y., S.C.K and P.Z. wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.SEER. Cancer Statistics Review 1975–2004 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreeff M, Ruvolo V, Gadgil S, Zeng C, Coombes K, Chen W, et al. HOX expression patterns identify a common signature for favorable AML. Leukemia. 2008;22(11):2041–2047. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, Huard C, Gaasenbeek M, Mesirov JP, et al. Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science. 1999;286(5439):531–537. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faber J, Krivtsov AV, Stubbs MC, Wright R, Davis TN, van den Heuvel-Eibrink M, et al. HOXA9 is required for survival in human MLL-rearranged acute leukemias. Blood. 2009;113(11):2375–2385. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tilly H, Castaigne S, Bordessoule D, Casassus P, Le Prise PY, Tertian G, et al. Low-dose cytarabine versus intensive chemotherapy in the treatment of acute nonlymphocytic leukemia in the elderly. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8(2):272–279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle kinases in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17(1):60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JK, Diehl JA. Nuclear cyclin D1: an oncogenic driver in human cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220(2):292–296. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fry DW, Harvey PJ, Keller PR, Elliott WL, Meade M, Trachet E, et al. Specific inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 by PD 0332991 and associated antitumor activity in human tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3(11):1427–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baughn LB, Di Liberto M, Wu K, Toogood PL, Louie T, Gottschalk R, et al. A novel orally active small molecule potently induces G1 arrest in primary myeloma cells and prevents tumor growth by specific inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6. Cancer Res. 2006;66(15):7661–7667. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marzec M, Kasprzycka M, Lai R, Gladden AB, Wlodarski P, Tomczak E, et al. Mantle cell lymphoma cells express predominantly cyclin D1a isoform and are highly sensitive to selective inhibition of CDK4 kinase activity. Blood. 2006;108(5):1744–1750. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Wang J, Blaser BW, Duchemin AM, Kusewitt DF, Liu T, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of CDK4/6: mechanistic evidence for selective activity or acquired resistance in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;110(6):2075–2083. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-071266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michaud K, Solomon DA, Oermann E, Kim JS, Zhong WZ, Prados MD, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 arrests the growth of glioblastoma multiforme intracranial xenografts. Cancer Res. 2010;70(8):3228–3238. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menu E, Garcia J, Huang X, Di Liberto M, Toogood PL, Chen I, et al. A novel therapeutic combination using PD 0332991 and bortezomib: study in the 5T33MM myeloma model. Cancer Res. 2008;68(14):5519–5523. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang X, Di Liberto M, Jayabalan D, Liang J, Ely S, Bretz J, et al. Prolonged early G(1) arrest by selective CDK4/CDK6 inhibition sensitizes myeloma cells to cytotoxic killing through cell cycle-coupled loss of IRF4. Blood. 2012;120(5):1095–1106. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-415984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leonard JP, LaCasce AS, Smith MR, Noy A, Chirieac LR, Rodig SJ, et al. Selective CDK4/6 inhibition with tumor responses by PD0332991 in patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2012;119(20):4597–4607. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-388298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finn RS, Crown JP, Lang I, Boer K, Bondarenko IM, Kulyk SO, et al. Results of a randomized phase 2 study of PD 0332991, a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitor, in combination with letrozole vs letrozole alone for first-line treatment of ER+/HER2− advanced breast cancer (BC) Cancer Res. 2012;72(24 Suppl) Supplement 3 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J, Shieh JH, Zhang J, Liu L, Zhang Y, Eom JY, et al. Improved ex vivo expansion of adult hematopoietic stem cells by overcoming CUL4-mediated degradation of HOXB4. Blood. 2013;121(20):4082–4089. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-455204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong F, Zhang J, Li Y, Hao X, Ren X, Li H, et al. Engineering a single ubiquitin ligase for the selective degradation of all activated ErbB receptor tyrosine kinases. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Morrone G, Zhang J, Chen X, Lu X, Ma L, et al. CUL-4A stimulates ubiquitylation and degradation of the HOXA9 homeodomain protein. Embo J. 2003;22(22):6057–6067. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keszler G, Spasokoukotskaja T, Csapo Z, Talianidis I, Eriksson S, Staub M, et al. Activation of deoxycytidine kinase in lymphocytes is calcium dependent and involves a conformational change detectable by native immunostaining. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67(5):947–955. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arner ES, Eriksson S. Mammalian deoxyribonucleoside kinases. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;67(2):155–186. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)00015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu YL, Passegue E, Fong S, Largman C, Lawrence HJ. Evidence that the Pim1 kinase gene is a direct target of HOXA9. Blood. 2007;109(11):4732–4738. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-043356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brumatti G, Salmanidis M, Kok CH, Bilardi RA, Sandow JJ, Silke N, et al. HoxA9 regulated Bcl-2 expression mediates survival of myeloid progenitors and the severity of HoxA9-dependent leukemia. Oncotarget. 2013 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorsteinsdottir U, Mamo A, Kroon E, Jerome L, Bijl J, Lawrence HJ, et al. Overexpression of the myeloid leukemia-associated Hoxa9 gene in bone marrow cells induces stem cell expansion. Blood. 2002;99(1):121–129. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sauvageau G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Eaves CJ, Lawrence HJ, Largman C, Lansdorp PM, et al. Overexpression of HOXB4 in hematopoietic cells causes the selective expansion of more primitive populations in vitro and in vivo. Genes Dev. 1995;9(14):1753–1765. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.14.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroon E, Krosl J, Thorsteinsdottir U, Baban S, Buchberg AM, Sauvageau G. Hoxa9 transforms primary bone marrow cells through specific collaboration with Meis1a but not Pbx1b. Embo J. 1998;17(13):3714–3725. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu F, Korc M. Cdk4/6 inhibition induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and enhances invasiveness in pancreatic cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11(10):2138–2148. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiron D, Martin P, Di Liberto M, Huang X, Ely S, Lannutti BJ, et al. Induction of prolonged early G1 arrest by CDK4/CDK6 inhibition reprograms lymphoma cells for durable PI3Kdelta inhibition through PIK3IP1. Cell Cycle. 2013;12(12):1892–1900. doi: 10.4161/cc.24928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.