Abstract

Proteases are recognized environmental allergens, but little is known about the mechanisms responsible for sensing enzyme activity and initiating the development of allergic inflammation. Because usage of the serine protease subtilisin in the detergent industry resulted in an outbreak of occupational asthma in workers, we sought to develop an experimental model of allergic lung inflammation to subtilisin and to determine the immunological mechanisms involved in type 2 responses. By using a mouse model of allergic airway disease, we have defined here that subcutaneous or intranasal sensitization followed by airway challenge to subtilisin induces prototypic allergic lung inflammation, characterized by airway eosinophilia, type 2 cytokines release, mucus production, high levels of serum IgE, and airway reactivity. These allergic responses were dependent on subtilisin protease activity, protease-activated receptor (PAR)-2, IL-33 receptor ST2, and MyD88 signaling. Also, subtilisin stimulated the expression of the pro-allergic cytokines IL-1α, IL-33, TSLP, and the growth factor amphiregulin in a human bronchial epithelial cell line. Notably, acute administration of subtilisin into the airways increased lung IL-5-producing type 2 innate lymphoid cells, which required PAR-2 expression. Finally, subtilisin activity acted as a Th2 adjuvant to an unrelated airborne antigen promoting allergic inflammation to inhaled OVA. Therefore, we established a murine model of occupational asthma to a serine protease and characterized the main molecular pathways involved in allergic sensitization to subtilisin that potentially contribute to initiate allergic airway disease.

Keywords: Allergic sensitization, Occupational asthma, Serine protease, Subtilisin, Protease-activated receptor (PAR)-2, MyD88, IL-33 receptor ST2, Epithelium, Lung inflammation

Introduction

The incidence and severity of allergic disease is on the rise, with 30-40% of the world population affected in 2011 (1). Asthma is considered a chronic inflammatory syndrome of the airways and represents one of the most studied lung diseases. Classically, asthma is triggered by the activation of a Th2 adaptive immune response that induces lung eosinophilia, mucus production, increased levels of IgE, and airway remodeling and hyperactivity (2). Despite the fact that allergic asthma is phenotypically well characterized, the mechanism behind allergen sensitization and initiation of the Th2 response is poorly understood.

Occupational asthma (OA) is a work-related lung disease induced by exposure to an occupational allergen. The prevalence of OA depends on the nature of the allergen workers are exposed to, the intensity and duration of this exposure, and individual susceptibility (3–5). Contact with proteases at the workplace is an important risk factor for the development of OA (4). Protease-induced OA was first recognized at the end of the 1960s and the 70s when heat-stable alkaline enzymes, like Carlsberg subtilisin, were introduced to washing detergents. After inclusion of Carlsberg subtilisin, more than 50% of workers from the detergent industry developed allergic asthma, IgE production and airway hyperactivity (6). This suggested that Carlsberg subtilisin (alcalase), a serine protease isolated from Bacillus species, acted as an allergen and could induce OA (7). However, despite the observed link between occupational exposure to subtilisin and asthma, the mechanisms through which subtilisin could triggers the allergic responses remained elusive. Therefore, the development of an experimental model for the investigation of subtilisin-induced allergic lung disease could provide useful insights into the general mechanisms behind allergic reactions to proteases.

Many allergens can initiate the allergic response, of which one important and understudied class is proteases. Protease activity has been implicated in the development of type 2 inflammation in response to allergens (8). Indeed, several studies suggest that proteases are an important component in the allergenic potential of urban substances (9–15). However, proteases do not always represent the major allergens. Even though, proteases could act as Th2 adjuvants to bystander antigens present in environment (8, 16, 17).

Here, we characterized an experimental model of OA to subtilisin induced by subcutaneous or intranasal sensitization. We found that subtilisin serine protease activity was essential for allergic sensitization and subsequent airway inflammation. Furthermore, we found that the allergenicity of subtilisin depended upon protease-activated receptor (PAR)-2, IL-33 receptor ST2, and MyD88. Moreover, exposure of a human bronchial epithelial cell line to subtilisin induced pro-allergic cytokines such as TSLP, IL-1α, IL-33, and the tissue repair factor, amphiregulin. Finally, inhaled subtilisin increased lung type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) and acted as a Th2 adjuvant to a bystander antigen such as inhaled OVA.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female (8-12 weeks old) C57BL/6 WT, MyD88-/-, PAR-2-/-, and TLR4-/- mice were from ICB-IV, University of Sao Paulo (Brazil) or Yale Animal Resources Center at Yale University (USA), originally from The Jackson Laboratory. C57BL/6 Il1rl1-/- mice were kindly provided by Andrew McKenzie (University of Cambridge). Mice were bred in specific pathogen-free conditions, and experiments were done in accordance with approved guidelines determined by the ethical principles of Animal Care of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences at University of Sao Paulo or Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Yale.

Chimeric mice were generated following a standard protocol (18). C57BL/6 CD45.1 and PAR-2-/- mice were used as donors and/or recipients in bone marrow transplant experiments. Recipient mice underwent a lethal total-body irradiation with 2 doses of 500 rad (Gammacell 40 137Cs γ-irradiation source), with an interval of 4 h between the first and second irradiations. Fresh, unseparated bone marrow cells (10 × 106 per mouse) were injected into the tail vein of the irradiated recipient mice 24 h after lethal irradiation. Chimerism efficiency was checked by FACS 8 weeks post irradiation and transplant using peripheral blood, and reconstituted mice were used at 2 mo after bone marrow transplantation.

Reagents and antibodies

Subtilisin (EC 3.4.21.62), papain (EC 3.4.22.2), grade V OVA and PMSF were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation. E-64, and the fluorogenic substrates AAF-AMC and Z-R-AMC were from Calbiochem Merck Millipore. OVA was removed from LPS using Triton X-114 and the remaining endotoxin activity was measured by LAL QCL-1000 kit (BioWhittaker). The following reagents are from the indicated sources: Ack lysing buffer (Lonza), FCS (Benchmark), SMART MMLV RT reagents (Clontech), SYBR Green QPCR mix (Quanta). Purified anti-mouse fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to CD16/CD32 (2.4G2), I-Ad and I-Ed, Siglec-F, CD4, CD8α, CD45, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17A, IFN-γ, lineage markers (CD3ε, CD19, CD11b, CD11c, NK1.1, Ly-6G, FcεRI), and Thy-1.2 (CD90.2) were all from BD Biosciences or eBioscience.

Enzymatic assays

Proteases assays were routinely performed at 30 °C with 10 mM of substrates in saline with 1 mM Ca2+ (subtilisin) or PBS with 5 mM L-cysteine (papain), both pH=7.4. Protease activity was measured by fluorescence detection of methylcoumarin released over time in a microplate fluorimeter (Gemini XPS, Molecular Devices). Enzyme activities were proportional to protein concentration and time. For inhibition assays subtilisin was heat-inactivated after incubation for 5 min at 100 °C. Protein and remaining protease activity were determined in the supernatant and precipitate after centrifugation for 10 min at 10.000× g and 4 °C. Alternatively, subtilisin and papain were incubated with different concentrations of PMSF or E64, respectively, until no further inhibition was detected prior to enzyme assay. For in vivo studies, 10 μM PMSF and 50 nM E-64 was used.

Induction of allergic airway inflammation

Mice were subcutaneously (s.c.) injected with 1 μg of subtilisin or 5 μg of papain with or without 1.6 mg of alum or intranasally (i.n.) with 1 μg of active or heat-inactivated subtilisin plus 5 μg of OVA on days 0 and 7. To induce airway inflammation after sensitization, anesthetized mice were administered i.n. with 1 μg of subtilisin, 5 μg of papain, or 10 μg of OVA in 40 μL of final volume on days 14 and 21. On day 22, mice were euthanized and different parameters were analysed. For the acute inflammation model, mice received 1 μg of i.n. subtilisin on days 0 and 7, and experiment was performed on day 8. For lung ILC2 studies, mice received 1 μg of subtilisin for 3 consecutive days and experiments were performed on day 4. Alum gel was prepared as previously described (19).

Analysis of inflammatory responses

BAL was collected after injecting 1 mL of PBS. Total and differential cell counts were determined by hemocytometer and cytospin preparation and stained with Instant-Prov (Newprov, Brazil). Lung tissue was digested using collagenase IV (2 mg/mL) and DNase I (1 mg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C for 30 min. Single cell suspension was obtained after erythrocyte depletion, smashing and filtering. Total lung cells were restimulated ex vivo with 100 ng/mL PMA and 750 ng/mL ionomicin (Sigma) for 4 h or 1 μg/mL subtilisin for 18 h both in RPMI-1640 medium at 37 °C.

Single-cell suspensions from BAL and lung were blocked with 2.4G2 and incubated for 25 min at 4 °C with antibodies. A Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus kit with GolgiPlug (BD Pharmingen) was used for intracellular cytokine staining according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cell acquisition was performed on Canto II or LSRII instruments (BD) and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Determination of respiratory pattern

Respiratory dynamics of mice was monitored using unrestrained whole-body plethysmography (Buxco Electronics, Inc., Troy, NY), and measurements were obtained at baseline and after stimulation with inhaled methacholine (0, 3, 6, 12 and 25 mg/ml) from Sigma-Aldrich as previously described (20). Enhanced pause (Penh) is a dimensionless value that represents a function of the ratio of peak expiratory flow to peak inspiratory flow and a function of the timing of expiration. Penh correlates with pulmonary airflow resistance or obstruction. Penh as measured by plethysmography has been previously validated in animal models of airway hyperresponsiveness (21).

To determine airway reactivity, Penh was recorded for 7.5 min after each methacholine challenge and at baseline. For late phase response analysis, Penh was measured each hour for 6 hours right after the second subtilisin challenge, on day 21 of the experimental protocol described in Materials and Methods. In this case, Penh was determined without methacholine challenge.

Determination of antibodies and cytokines

Total IgE was assayed by sandwich ELISA (OptEIA ELISA Set BD) following the manufacturer's instructions. For specific IgG1 quantification, OVA or subtilisin (both at 2 μg/mL) was plated overnight at 4 °C. Plates were blocked with 10% FBS, mouse serum was added at multiple dilutions and specific IgG1 was detected with HRP anti–mouse IgG1 (Invitrogen). Purified mouse IgG1 (Invitrogen) was used as standard. For OVA-specific IgE, plates were coated with anti-IgE (SouthernBiotech) and subsequently biotin-labelled OVA was added. Bound OVA–biotin was revealed and OVA-specific IgE levels of samples were deduced from an internal standard arbitrarily assigned as 1000 U, as previously established (22).

BAL specimens were assessed for concentrations of IL-4, IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α at day 22 after s.c. sensitization and i.n. challenge with subtilisin by cytometric bead array using the BD™ CBA Mouse Th1/Th2/Th17 Cytokine Kit, (BD Biosciences), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were quantified using Canto II (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer and analyzed by FCAP array™ software (BD).

Lung histology

Lungs were perfused through the right ventricle with 5 mL PBS, removed, and immersed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin for 24 h followed by 70% ethanol until embedding in paraffin. Tissues were sliced and 5 μm sections were stained with hematoxylin/eosin or periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) for analysis of cellular inflammation and mucus production, respectively.

Analysis of human epithelial cell activation

Human airway epithelial cells (H292, ATCC) were cultured as indicated by the manufacturer. Confluent cultures were serum-starved for 12 h before the addition of active subtilisin (1.0 or 10 μg/mL) or papain (10 μg/mL). Cell lysates were harvested after stimulation for 3 or 6 h. Total RNA was isolated using RNA-Bee reagent and was reverse-transcribed with an oligo (dT) primer and MMLV RT. cDNA was synthesized by SuperScriptIII (Roche) and random primers, and analyzed in triplicate by qPCR amplification using SYBR Green Supermix on a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System. Relative expression was normalized to ribosomal protein L22 (Rpl22a). Data are represented as the relative fold induction over unstimulated cells and are representative of three independent experiments, each of them with triplicate samples.

Study subjects

Three healthy non-atopic and non-smoking female individuals, 23-34 years old, with no family history of asthma and allergy were chosen to participate in the study. All volunteers gave written, informed consent. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (2009/902 CEP).

Dendritic cell (DC) differentiation and allergen pulse

PBMCs were isolated from blood collected in heparin (50 U/ml) by centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) as previously described (23). Briefly, mononuclear cells were resuspended and seeded in RPMI-1640 culture medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), supplemented with 10% FCS (Gibco) plus antibiotic-antimycotic (100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 25 μg/ml amphotericin; Gibco). Culture plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight and non-adherent cells were cultured with GM-CSF (50 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and IL-4 (50 ng/ml; R&D Systems). Monocyte-derived immature DCs (Mo-iDCs) were harvested at day 7 and stimulated overnight with 1μg/mL of active or heat-inactivated subtilisin. Cells stimulated with 500 ng/mL of LPS (E. coli 0111:B4; Sigma-Aldrich) were taken as positive control whereas unstimulated cells (in serum-free medium) were used as negative control. On day 8, non-adherent mature DCs were harvested and 2.5×105 cells/condition were labeled with specific fluorescent antibodies (CD11c, CD14, CD80, CD83, CD86, HLA-DR or isotype controls, all from BD Biosciences or eBiosciences) and acquired on Canto II flow cytometer. Samples were analyzed using the FlowJo software (Tree Star, USA).

T cell stimulation assay

Eight days after initiation of Mo-DCs culture, heterologous non-adherent lymphocytes were obtained from healthy volunteers. Mo-mDCs pulsed with active, heat-inactivated subtilisin or LPS were co-cultured in 96-well U-bottom culture plates with heterologous lymphocytes, in triplicates at a ratio of 1:10 in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS plus antibiotic-antimycotic solution. After 5 days of co-culture, CD3+ T cells were phenotypically evaluated as to their cytokine production after intracellular staining for IL-4, IL-10, TNF-α, and IFN-γ (all antibodies and isotype controls are from BD Biosciences or eBiosciences).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with t tests (Mann-Whitney for unpaired data) or ANOVA, as appropriate. Differences were considered significant when p value < 0,05 (*), p < 0.01 (**) or p < 0.005 (***) related to control group or (•) to protease-administered group.

Results

Experimental model of occupational asthma (OA) induced by subtilisin

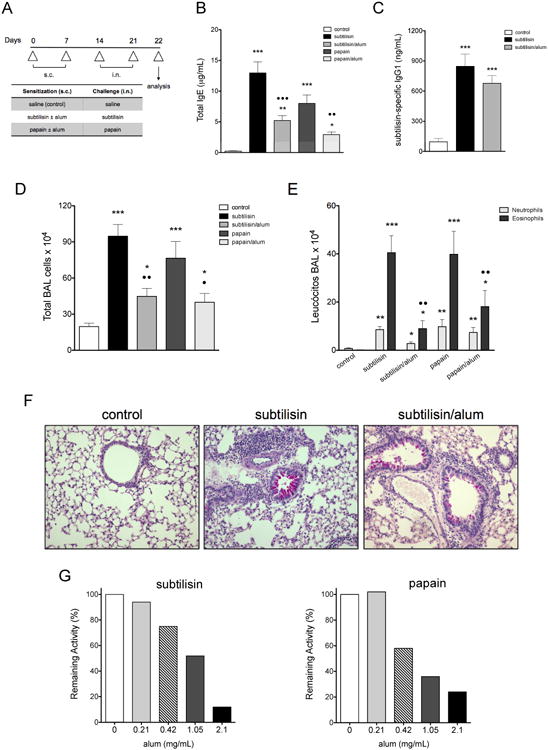

To establish a model of subtilisin-induced OA mice were sensitized with two subcutaneous (s.c.) sensitization followed by two intranasal (i.n.) challenges as depicted in Figure 1A and as previously described (24). Sensitization and challenge with subtilisin induced high levels of serum IgE, and this production was enhanced when mice were sensitized to subtilisin in the absence of alum (Fig. 1B). The specific IgG1 response induced by subtilisin was also increased in sensitized and challenged animals, and it was similar in magnitude comparing sensitization with or without alum (Fig. 1C). We found that administration of subtilisin without adjuvant during sensitization induced an intense airway eosinophilic inflammation, as revealed by total (Fig. 1D) and differential cell counts (Fig. 1E) in BAL. Similar results were obtained using papain, a cysteine protease known to induce occupational allergy (25) (Fig. 1B, 1D, and 1E). Lung histology showed pronounced airway inflammation and mucus formation in mice sensitized to subtilisin alone compared with subtilisin/alum or control groups (Fig. 1F). Moreover, subtilisin challenge promoted increased bronchoconstriction to inhaled methacholine, a hallmark of asthma, (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Interestingly, subtilisin was also able to induce the late phase response in sensitized mice, characterized by altered respiratory pattern after specific allergen challenge (26) (Supp. Fig. 1B). Together, these data demonstrate that subtilisin by itself is a potent inducer of allergic lung disease.

FIGURE 1.

Airway allergic inflammation induced by subtilisin. (A) Experimental protocol for the development of allergic airway inflammation. C57BL/6 mice were s.c. sensitized with subtilisin or papain with or without alum on days 0 and 7 and i.n. challenged with the respective enzyme on days 14 and 21. Control groups received saline and samples were harvested on day 22, 24 h after the last enzyme challenge. (B) Total serum IgE and (C) subtilisin-specific IgG1. BAL (D) total and (E) differential cell counts. (F) Representative lung sections (200×) showing mucus production and peribronchovascular cellular infiltrates. (G) Remaining specific enzymatic activities of subtilisin (left) and papain (right) after incubation with different concentrations of alum. Error bars show ***, P ≤ 0.0001; **, P ≤ 0.001; *, P ≤ 0.01 for significant differences to control group or • to protease without alum group. Data are mean ± SEM and are representative of three independent experiments (n=5) (B-E) or are representative of, at least, five experiments (F).

Since mice sensitized with protease plus alum, a pro-Th2 adjuvant, showed decreased Th2 responses compared to mice sensitized with protease alone, indicating that alum could interfere with subtilisin allergenicity. We found that alum reduced protease activity in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 1G), suggesting that protease activity might play a role in the allergenicity of subtilisin.

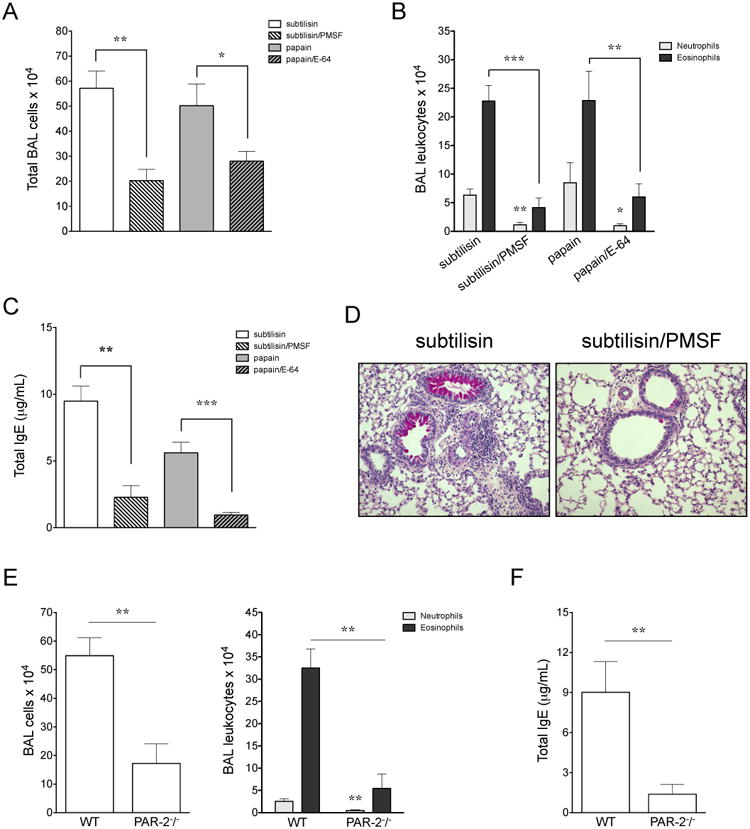

Protease activity of subtilisin initiates the development of allergic inflammation through PAR-2

We next sought to determine if the allergenicity of subtilisin depended upon its protease activity. Incubation of subtilisin or papain with specific inhibitors, PMSF or E-64 respectively, virtually eliminated protease activity (93-97% of inhibition, data not shown). Sensitization of mice with pharmacologically inactivated subtilisin reduced recruitment of inflammatory cells to the airways after challenge with active protease (Fig. 2A, 2B). Analysis by flow cytometry confirmed that sensitization with inactive subtilisin prevented eosinophil (Siglec-F+ MHC II- cells) and neutrophil (Gr1hi MHC II- cells) influx to the airways and to the lungs (Supp. Fig. 2A). Furthermore, subtilisin protease activity was required for enhanced IL-4 production by lung CD4+ T cells; no IFN-γ was detected (Supp. Fig. 2B). Accordingly, sensitization with active subtilisin led to an increased frequency (Supp. Fig. 2C) and number (data not shown) of Gata-3-expressing CD4+ T cells in the lungs. No changes in Tbet-, Foxp3- or Rorc- expressing T cells were observed comparing both groups (Supp. Fig. 2C). In addition, protease activity was essential for the induction of total IgE antibodies (Fig. 2C) and mucus production (Fig. 2D). Consistent with a previous report (15), enzymatic activity of papain was also essential for the development of allergic airway inflammation and IgE production (Fig. 2A-C). Of note, subtilisin activity was required only during sensitization for the development of allergic inflammation, as sensitization with active subtilisin and further challenge with the inactivated form did not prevent the establishment of allergic lung disease (data not shown). Also, heat-inactivation of subtilisin worked equally well to inactivation by PMSF for both in vitro and in vivo experiments (data not shown). Together, our results indicate that Th2 responses to subtilisin were dependent on its protease activity.

FIGURE 2.

Subtilisin serine protease activity and signaling through PAR-2 are both essential for the development of Th2 responses. C57BL/6 mice were s.c. sensitized with active or inactivated form of the enzyme, 10 μM of PMSF for subtilisin or 50 nM E-64 for papain, on days 0 and 7 and i.n. challenged with the active enzyme on days 14 and 21. Samples were harvested 24 h after the last i.n. administration, on day 22. BAL (A) total and (B) differential cell counts. (C) Total serum IgE. (D) Representative lung sections (200×). C57BL/6 WT or PAR-2-/- mice were sensitized with s.c. subtilisin on days 0 and 7 and i.n. challenged on days 14 and 21. (E, left) Total number of cells from BAL recovered on day 22. (E, right) BAL neutrophil and eosinophil numbers from WT or PAR-2-/- mice by morphological analysis. (F) Total serum IgE. *Significant differences when compared with sensitization to active protease (A-C) or with WT group (E, F). Data are mean ± SEM and are representative of three independent experiments (n=5).

Proteolytic activity can be directly sensed through a unique class of G protein-coupled molecules, the protease-activated receptors (PAR) (27). Because PAR-2 has been implicated in allergic inflammation (28), we aimed to determine the role of PAR-2 in subtilisin-induced airway inflammation. We found that PAR-2-deficient mice showed reduced eosinophil and neutrophil recruitment to the airways in response to subtilisin sensitization as compared with WT mice (Fig. 2E). IgE production was also reduced in subtilisin-sensitized PAR-2-deficient mice (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, frequency and numbers of lung IL-5- and IL-13-producing T cells (CD3+ CD4+) were decreased in PAR-2 deficient mice (Supp. Fig. 2D, and data not shown, respectively). These data suggest that subtilisin initiation of allergic inflammation in the lung depends upon PAR-2.

Allergic sensitization to subtilisin is dependent on MyD88 adaptor molecule, but not TLR4

Innate signals have been increasingly recognized as fundamental for the initiation of allergic sensitization. MyD88 is the central signaling adaptor molecule for the TLRs and for the IL-1 family of cytokines (29) and for the initiation of some Th2-mediated responses (30). Some groups reported an important role of TLR4 in allergic inflammation induced by airborne allergens in house dust mite (31) or to the development of hypersensitivity contact in humans caused by nickel (32). Therefore, we wished to determine the role of MyD88 and TLR4 in Th2 responses induced by subtilisin. Airway eosinophilia was significantly reduced in subtilisin-sensitized MyD88-deficient mice, while no change was verified in TLR4-deficient mice (Supplemental Fig. 3A, 3B, 3D top). Total serum IgE and frequency of IL-5-producing lung T cells from MyD88-deficient mice were similarly decreased, whereas no significant changes were observed in TLR4-deficient mice (Supp. Fig. 3C, 3D bottom). The inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-6, and TNF-α as well as IL-10 were increased in the airways of both sensitized WT and TLR4-deficient mice, but not in MyD88 (Supplemental Fig. 3E). Thus, signaling through MyD88 adaptor molecule is essential for subtilisin-induced allergic lung inflammation. Because allergic responses to subtilisin were intact in TLR4-deficient mice, we also exclude a possible endotoxin contamination in subtilisin samples. Our data suggest there is another receptor that is required for the allergic response to subtilisin that signals through MyD88.

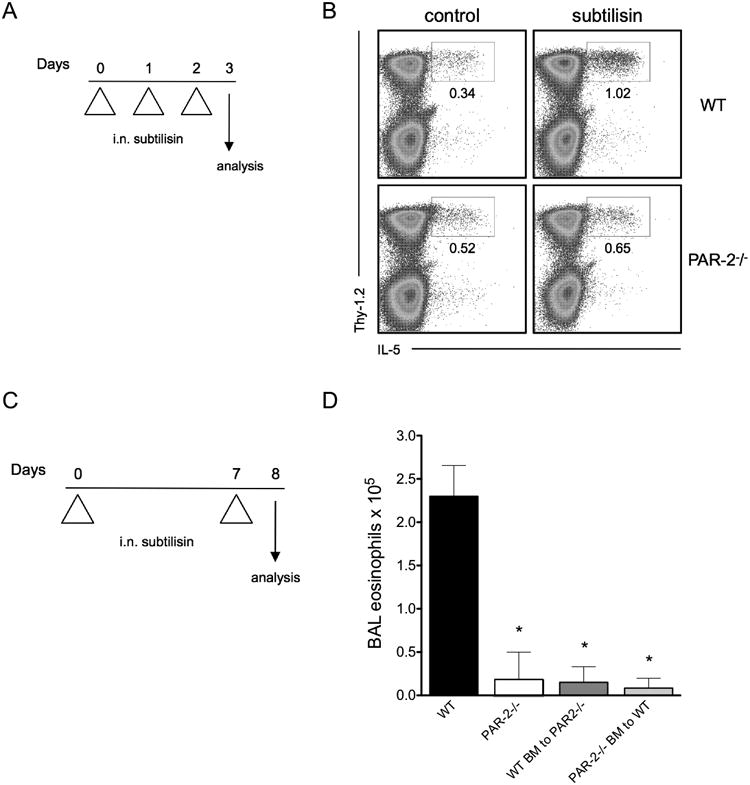

Subtilisin increases lung type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) frequency dependent on PAR-2

Type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) are innate producers of type 2 cytokines and have been increasingly recognized as inducers of type 2 immunity (33). Because ILC2s are constitutively present in mouse lung tissue (34), we examined ILC2 activation by administration of subtilisin into the airways. Notably, acute i.n. administration of subtilisin for 3 consecutive days (Fig. 3A) increased the frequency of IL-5-producing lung ILC2s (characterized by negative expression of the lineage markers CD3, CD19, CD11b, CD11c, Gr1, NK1.1, and positive expression of Thy-1.2+) (Fig. 3B). Next we asked the role of PAR-2 on subtilisin-induced ILC2 activation in the lung. Interestingly, the increased frequency of lung ILC2 in response to acute airway sensitization to subtilisin was dependent on PAR-2 (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Role of PAR-2 in the induction of lung ILC2 and eosinophilia promoted by airway exposure to subtilisin. (A) To analyze lung group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2), C57BL/6 WT or PAR-2-/- mice received i.n. subtilisin for three consecutive days and lung cells were analyzed on day 4. (B) FACS plots show lung ILC2, as defined by CD45+Lin-Thy-1.2+, after ex vivo stimulation with PMA and ionomycin to induce cytokine production. (C) Experimental protocol used to promote allergic inflammation by airway sensitization to subtilisin. WT, total PAR-2-/-, and the mixed chimera (WT BM to PAR-2-/- and PAR-2-/- BM to WT) mice were i.n. sensitized with 1 μg subtilisin on days 0 and 7, and samples were harvested on day 8. (D) Number of BAL eosinophils from subtilisin-administered mice. Error bars show *, P ≤ 0.01, for significant differences to WT group. Data are mean ± SEM and are representative of two independent experiments (n=5-9 mice per group).

Since lung ILC2s were induced by intranasal exposure to subtilisin, we further decided to explore airway sensitization to this protease in the development of allergic inflammation. For this, we adapted for subtilisin a previously described protocol for papain (8), that consisted of two i.n. administrations with active subtilisin on days 0 and 7 (Fig. 3C). BAL cell counts on day 8 showed that subtilisin treatment induced eosinophilia that depended on PAR-2 expression (Fig. 3D). Finally, because both epithelial cells and hematopoietic cells express PAR-2 (27, 35, 36), we generated mixed bone marrow (BM) chimeras that would allow us to examine independently the contribution of different cell types expressing PAR-2. For this, irradiated PAR-2-/- mice were reconstituted with WT BM (referred as WT BM to PAR-2-/-), and vice-versa (PAR-2-/- BM to WT). Neither of the mixed BM chimeras developed lung eosinophilia in response to subtilisin, suggesting that PAR-2 expression is important in both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic compartments for protease induced development of allergic response to subtilisin (Fig. 3D).

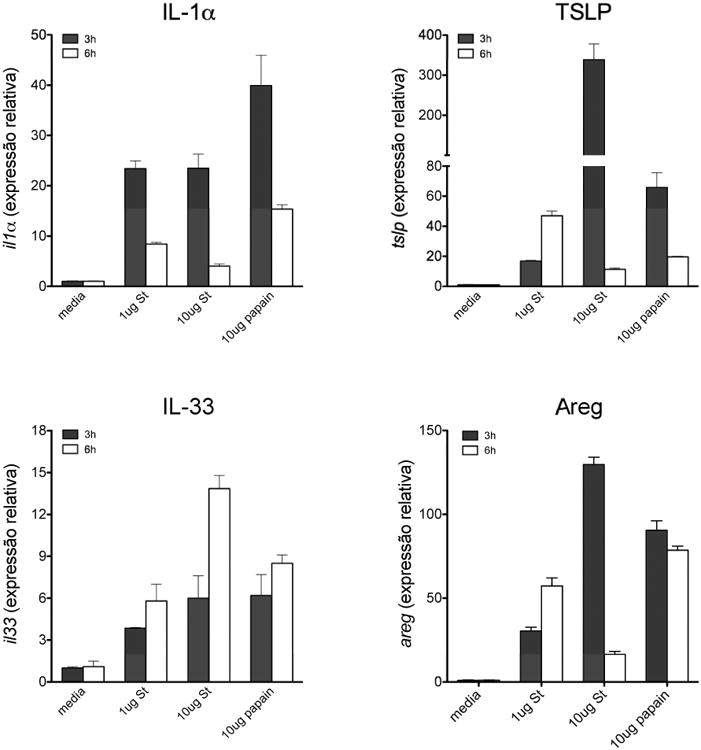

Subtilisin stimulates airway epithelial cells to express pro-Th2 cytokines

Epithelial cell-derived factors have been implicated in allergic sensitization (37) and it is known that some of these molecules induce ILC2 activation (38). Hence, we investigated whether subtilisin activates epithelial cells and induces expression of pro-allergic cytokines. For this, we analyzed early gene expression of IL-1α, TSLP, and IL-33 in a human bronchial epithelial cell line, H292. Subtilisin treatment induced these cytokines in a dose dependent manner 3 h after stimulation, except for IL-33 whose expression peaked at 6 h (Fig. 4). Papain also induced expression of the same cytokines in H292 cells (Fig. 4), however the intensity and kinetics were different than seen with subtilisin treatment, suggesting that these proteases might activate the epithelium through distinct pathways (Fig. 4). Interestingly, subtilisin or papain also enhanced the expression of amphiregulin (Areg), an EGF family member that promotes proliferation, tissue repair and was previously recognized as a Th2 cytokine (39). Similar results were obtained using a murine lung epithelial cell line, LA-4 (data not shown). We did not find that either subtilisin or papain induced expression of IL-25 (IL-17E), a cytokine previously shown to induce Th2 responses (40) (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Subtilisin stimulates airway epithelial cells to express pro-Th2 cytokines and amphiregulin. Expression of mRNA from IL-1α (top left), TSLP (top right), IL-33 (bottom left), and amphiregulin (bottom right) in human bronchial epithelial cell line (H292) stimulated with active subtilisin or papain for 3 or 6 h at the indicated concentrations. FACS plots are representative of two independent experiments (n=5 per group). Data are mean ± SEM and are representative of three independent experiments, each of them with triplicate samples.

Dendritic cells (DCs) have been reported to play a pivotal role in the initiation of type 2 inflammation (41–43). To see whether the subtilisin promoted DC activation, we generated human DCs as described before (23). Our results show that active subtilisin was not able to induce expression of HLA-DR, CD80, CD83 or CD86 on immature DCs when compared with the positive control stimulated with LPS (Supplemental Fig. 4A). Similar data were obtained by using murine BM-derived DCs (data not shown). Furthermore, subtilisin-pulsed human DCs could not polarize CD3+ T cells to a Th2 phenotype (Supplemental Fig. 4B). Thus, we hypothesize DCs might not be the main cell type that senses subtilisin and triggers type 2 immunity, at least, not in a direct way. Because basophils were implicated in the initiation of type 2 responses to papain (14), we also determined the effect of subtilisin stimulation on bone marrow-derived basophils, generated as previously described (44). Using the 4get reporter system, we did not find significant IL-4 production by murine basophils stimulated with active subtilisin when compared with the positive control stimulated with papain (data not shown). Thus, our data suggest that subtilisin allergenicity works through induction of epithelial cell pro-Th2 cytokine production.

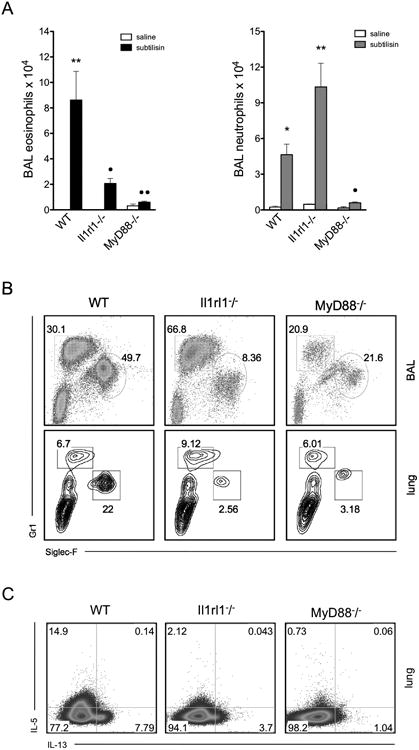

Allergic inflammation to i.n. subtilisin requires the IL-33 receptor, ST2, and MyD88

Given that our previous results indicated an important role for MyD88 during s.c. sensitization with subtilisin, we questioned whether this pathway was important during i.n. subtilisin exposure. MyD88-deficient mice exhibited impaired recruitment of inflammatory cells in BAL and a reduced frequency of IL-5- and IL-13-producing lung T cells (Fig 5A-C; number of cells, data not shown). These data indicate that MyD88 signaling is required for the development of allergic airway responses to subtilisin.

FIGURE 5.

Subtilisin-induced Th2 responses are dependent upon MyD88 and IL-33-receptor ST2. C57BL/6 WT, MyD88-/- or Il1rl1-/- (ST2-/-) mice were sensitized with i.n. subtilisin on days 0 and 7. Control groups received saline and samples were harvested on day 8. (A) BAL granulocytes (eosinophils are shown on the left, and neutrophils on the right). (B) FACS plots show frequency of MHCII-CD3-CD19- cells from BAL (top) or lung (bottom) of subtilisin-sensitized groups. (C) FACS plots show IL-5 and IL-13 production by lung conventional T cells (CD45+CD3+CD4+) cells after stimulation with PMA and ionomycin. Error bars show **, P ≤ 0.001; *, P ≤ 0.01 for significant differences to control group or • to subtilisin-sensitized C57BL/6 WT. Data are mean ± SEM and are representative of two independent experiments (n=5).

The epithelial-derived cytokine IL-33 is a potent inducer of ILC2 (45) and implicated in the development of type 2 immunity (46). Furthermore, the IL-33 receptor, ST2 (Ilrl1), is known to signal through MyD88 (30). Given that our data indicated the importance of MyD88 for subtilisin allergenicity, we investigated the role of IL-33 receptor signaling in the initiation of allergic inflammation to subtilisin. Mice lacking ST2 (Ilrl1-/-) had impaired eosinophil recruitment (Fig. 5A, left) while neutrophil recruitment was increased (Fig. 5A, right). Similar results were found by FACS analysis, as the frequency of eosinophils (Siglec-F+ MHCII- cells) was substantially reduced while neutrophil (Gr1+ MHCII- cells) frequency was increased in the airways (Fig. 5B, top) and lungs (Fig. 5B, bottom) of ST2-deficient mice. Moreover, ST2-deficient mice showed reduced IL-5 and IL-13-production by lung conventional T cells (CD3+ CD4+) (Fig. 5C). Our results suggest that subtilisin induces a Th2 response through activation of IL-33/ST2 receptor that, in turn, signals through MyD88 (47).

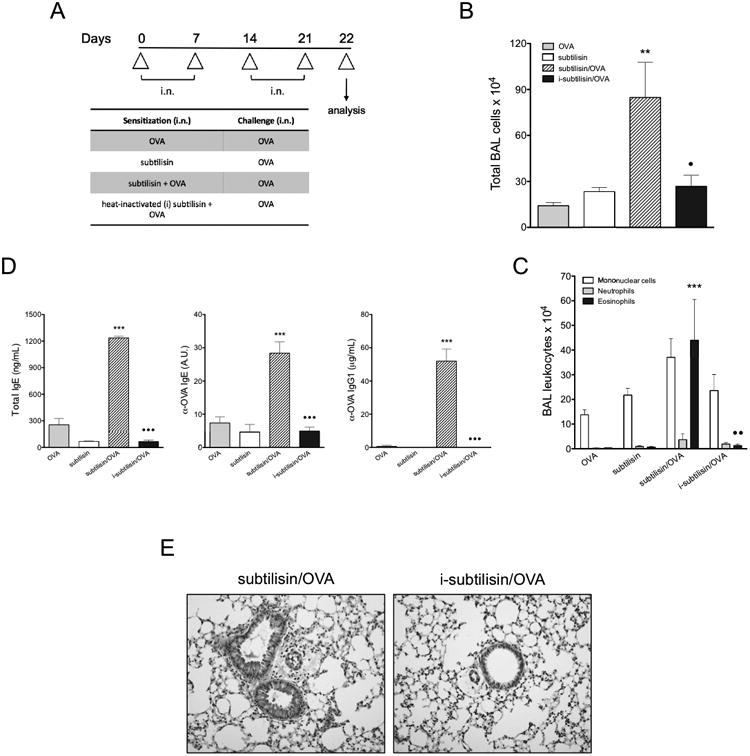

Subtilisin can act as adjuvant and sensitize the airway to a bystander antigen

Because subtilisin activated lung innate allergic responses, we tested whether this serine protease might behave as a Th2 adjuvant to a bystander antigen. We chose to use OVA as the antigen, since its intranasal administration does not result in allergic inflammation (48). WT mice i.n sensitized with subtilisin and OVA on days 0 and 7 and i.n. challenged with OVA alone on days 14 and 21 (Fig. 6A) showed an intense cellular influx to the airways mainly composed by eosinophils on day 22 (Fig. 6B, 6C). Our results also showed increased total IgE, OVA-specific IgE and IgG1 antibodies (Fig. 6D), and mucus formation (Fig. 6E) in mice i.n. sensitized with both OVA and active subtilisin. The i.n. administration of OVA and heat-inactivated subtilisin did not induce airway allergic inflammation, production of Th2-related antibodies, or mucus secretion triggered by OVA challenge (Fig. 6B-6E), which indicates the requirement of subtilisin protease activity for OVA sensitization. Our data suggest that subtilisin promotes allergic inflammation to unrelated proteins.

FIGURE 6.

Subtilisin has adjuvant activity to a bystander antigen through airway sensitization. (A) C57BL/6 mice were i.n. administered with OVA plus active or heat-inactivated subtilisin and challenged with OVA. (B) Total (left) and differential (right) cell counts in BAL. (C) Serum concentrations of total IgE (left), OVA-specific IgE (middle) and OVA-specific IgG1 (right). (D) Representative lung sections (200×). Error bars show ***, P ≤ 0.0001; **, P ≤ 0.001; *, P ≤ 0.01 for significant differences to control groups or • to group sensitized with active subtilisin. Data are mean ± SEM and are representative of three independent experiments (n=5).

Discussion

Subtilisin was identified as a potent allergen soon after its usage in the detergent industries (49, 50). Two decades ago, experimental models evaluated the allergenic potential of Carlsberg subtilisin (51–54), however the mechanism was not elucidated. Here, we developed a murine model of subtilisin-induced allergic airway disease and demonstrated that this enzyme is a potent inducer of type 2 immunity, including Th2 and ILC2 responses, and IgE production in mice. Our data show that the ability of subtilisin to induce Th2 response is dependent on its serine protease activity and on the expression of PAR-2, IL-33 receptor ST2, and MyD88. These data support the hypothesis that detection of enzymatic activities in allergens can promote Th2 and IgE responses (55, 56) and offer a more integrated view of the innate mechanisms responsible for the development of type 2 inflammation to a serine protease.

The present study confirms, in a murine model of allergic asthma, the sensitization potential of subtilisin and extends its allergenic action to other classical features of occupational asthma rather than specific IgE and IgG1 antibody production such as airway and lung eosinophilia, mucus production, type 2 cytokine production by lung Th2 cells, airway hyperreactivity and late phase response. Notably, low concentrations of subtilisin could promote these hallmarks of allergic asthma in the absence of alum, a strong type 2 adjuvant. In fact, our work indicates that usage of alum does not represent a good immunization strategy to maximize the response to proteases because alum impairs both serine and cysteine enzymatic activities.

We showed subtilisin is, by itself, a potent inducer of type 2 immunity and suggested that its serine protease activity is responsible for the development of Th2 responses. Accumulating evidence suggest that intrinsic proteolytic activity not only facilitates allergen sensitization, but also diminishes epithelial barrier integrity, enhances cytokine and chemokines expression as well as affects lung chronic inflammation and directs airway remodeling followed by interactions with bronchial epithelium (57, 58). Some mechanisms involved in the induction of Th2 response described to serine proteases have in common the activation of PAR-2 (27, 59, 60). Indeed, we found a critical role for this direct protease sensor in the development of allergic responses to subtilisin. Recently, Page et al showed PAR-2 contribution to allergic inflammation to german cockroach proteases in feces (frass) only when the allergen was administered through the airway mucosa, but not into the peritoneal cavity (59). In our work PAR-2 was found to be required when subtilisin was administered either subcutaneously or intranasally.

Because airway epithelial cells responded fast and directly to subtilisin in vitro by expressing pro-allergic cytokines, we predict that the Th2-inducing effects of subtilisin might be largely dependent on the activation of PAR-2 on epithelial cells. It was shown that signaling through this receptor triggered by the recognition of enzymatic activity leads to TSLP production in epithelial cells from the respiratory tract (61). This production can, in turn, enhances OX-40L expression in DCs and promotes effector functions of basophils and other granulocytes (62). But besides its important role in airway sensitization to subtilisin, PAR-2 was also important in subcutaneous sensitization, suggesting other cell types such as keratinocytes might be involved in allergic response to this enzyme. Accordingly, mite proteases were shown to promote allergic inflammation through PAR-2 activation of human keratinocytes (60) and a recent work also evidenced the role of this receptor in a model of atopic dermatitis (63). Interestingly, however, is the fact that PAR-2 expression was important in hematopoietic cells as well as in nonhematopoietic compartment for the allergic process promoted by subtilisin. This indicates epithelial cells might not be the only cell type responsible for subtilisin allergic response.

A recent report showed a direct effect of a cockroach serine protease, Per a 10, on human DC activation and T cell polarization towards a Th2 phenotype and suggested enzymatic activity as the major responsible (64). For the cysteine protease papain, Sokol et al. proposed that basophils are a possible cell type responsible for the initiation of allergic response through TSLP production (15) and two recent studies characterized a particular DCs subset required for the development of Th2 immunity in response to papain (42, 43). In our work, the serine protease subtilisin was unable to directly activate DCs or basophils and promote further Th2 differentiation. However, subtilisin activated human epithelial cells to enhance expression of pro-allergic cytokines, which could, in turn, act on DCs and promote type 2 immunity, as previously shown for IL-33 and TSLP (65, 66).

Importantly, we found that subtilisin is a potent inducer of ILC2 in the lung and this is also dependent on PAR-2 expression. This newly identified cell subset represent a large proportion of IL-5- and IL-13-producing cells in the lungs (38). Also, it has been shown that mice deficient in ILC2 cells showed decreased lung inflammation after intranasal papain (67). A detailed study investigating the contribution of ILC2 and PAR-2 will be necessary for better understanding the interaction between innate and adaptive immunity during type 2 responses.

A few studies have highlighted the critical role of IL-33/ST2 in type 2 inflammation and allergic disease states (46). IL-33 plays a role in innate type 2 responses by inducing the expansion of ILC2, which produce IL-5 and IL-13 and contribute to respiratory or gastrointestinal inflammation and anti-helminth responses (68). Furthermore, a role for MyD88 and ST2 in driving the Th2 response to Trichinella spiralis has recently been demonstrated (69). We found here that ST2 is required for the induction of subtilisin-induced Th2 responses. Furthermore, MyD88 expression is essential for optimal Th2 responses to subtilisin. Because prevention of allergic response to subtilisin is more pronounced in MyD88-deficient mice than in ST2-mice, we hypothesize that other cytokine, which also signals through the same adaptor rather than IL-33, might play an important role in our model.

It was previously shown that PAR-2 and TLR4 receptors, through MyD88, synergistically cooperate to inflammatory responses (70), however we could not find a role for TLR4 signaling in our model. Although PAR-2 was essential for the induction of Th2 responses in our model, a recent study demonstrated that induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines by house dust mite exposure is independent of PAR-2 (71), indicating that alternative pathways, besides PAR-2, could be involved in protease-mediated inflammation. For example, papain has been shown to induce IL-4 production in basophils because it requires calcium flux, activation of PI3K, and nuclear factor of activated T cells through a yet unknown receptor (44). The challenge for future studies, therefore, is to determine the direct sensor in each case and their respective biological contribution to the development of type 2 inflammation.

Based in our in vitro data with epithelial cell line and work from Hammad et al (72), we hypothesize that IL-1α might be also important in allergic responses to subtilisin. IL-1α and IL-33 cytokines, also known as alarmins, are sensors of tissue distress. Subtilisin also promoted enhanced expression of the tissue repair factor amphiregulin. As these molecules were induced in epithelial cells in vitro, some level of injury in vivo is anticipated, however, we could not detect alterations indicating rupture of lung structure, besides inflammation, when analyzing lung sections. Nevertheless, independently of the degree of tissue damage, our results indicate that PAR-2, ST-2 and MyD88 molecules are crucial to induce allergic responses.

The way workers in the detergent industry were sensitized to serine proteases remains to be elucidated. Consistent with data shown here, they could have been sensitized by either epicutaneous route or aerosol inhalation. In addition to directly sensitize mice through the airways, subtilisin showed a strong Th2 adjuvant activity to a bystander innocuous OVA protein. This indicates that airway exposure to subtilisin can promote allergic response to the enzyme itself or to a neo airborne antigen, therefore increasing the risk to develop asthma to environmental proteins.

Taken together, our data indicate that allergenic effect of subtilisin enzyme activity depends on PAR-2, IL-33/ST2 and MyD88 signaling pathways. These observations have implications in allergy models induced by proteases. In conclusion, our study defines a new model of occupational asthma induced by the serine protease subtilisin and provides another example of how protease sensing induces conserved type 2 immunity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank members of the Russo and Medzhitov laboratory, specially Daniel Okin and Tanya Bondar, for helpful and crucial discussions, Cuiling Zhang from the Medzhitov laboratory for technical assistance in the generation of PAR-2 chimeras, Clélia Ferreira and Walter Terra from the Department of Biochemistry, University of Sao Paulo, for collaboration and expert advice on enzymology, Charles Annicelli and Sophie Cronin for animal care and technical help at Yale University, and Andrew McKenzie for making available the Il1rl1-/- mice.

This work was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa, Brazil; National Institutes of Health and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, USA.

Abbreviations

- AAF-AMC

Ala-Ala-Phe 7-amido-4-methyl coumarin

- BAL

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- E-64

Trans-epoxysuccinyl L-leucylamido(4-guanidine)butane

- ILC2

Innate lymphoid cells type 2

- i.n

Intranasal

- OA

Occupational asthma

- PAR

Protease-activated receptor

- s.c

Subcutaneous

- TSLP

Thymic stromal lymphopoietin

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- Z-R-AMC

Carbobenzoxi-arginin-7-amido-4-metilcoumarin

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare they have no competing financial interests

References

- 1.Pawankar R, Canonica GW, Holgate ST, Lockey RF. WAO White Book on Allergy 2011-2012: Executive Summary. World Allergy Organization; [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim HY, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. The many paths to asthma: phenotype shaped by innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:577–84. doi: 10.1038/ni.1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maestrelli P, Boschetto P, Fabbri LM, Mapp CE. Mechanisms of occupational asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:531–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.01.057. quiz 543–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baur X. Enzymes as occupational and environmental respiratory sensitisers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2005;78:279–86. doi: 10.1007/s00420-004-0590-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dykewicz MS. Occupational asthma: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:519–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.01.061. quiz 529–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schweigert MK, Mackenzie DP, Sarlo K. Occupational asthma and allergy associated with the use of enzymes in the detergent industry-a review of the epidemiology, toxicology and methods of prevention. Clin Exp allergy. 2000;30:1511–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemière C, Cartier A, Dolovich J, Malo JL. Isolated Late Asthmatic Reaction After Exposure to a high-molecular-weight occupational agent, subtilisin. Chest. 1996;110:823–824. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.3.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamijo S, Takeda H, Tokura T, Suzuki M, Inui K, Hara M, Matsuda H, Matsuda A, Oboki K, Ohno T, Saito H, Nakae S, Sudo K, Suto H, Ichikawa S, Ogawa H, Okumura K, Takai T. IL-33-Mediated Innate Response and Adaptive Immune Cells Contribute to Maximum Responses of Protease Allergen-Induced Allergic Airway Inflammation. J Immunol. 2013:1–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shafique RH, Klimov PB, Inam M, Chaudhary FR, OConnor BM. Group 1 Allergen Genes in Two Species of House Dust Mites, Dermatophagoides farinae and D. pteronyssinus (Acari: Pyroglyphidae): Direct Sequencing, Characterization and Polymorphism. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen HD, Tam MF, Tang RB, Chou H. Aspergillus and Penicillium allergens: focus on proteases. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2007;7:351–6. doi: 10.1007/s11882-007-0053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sudha VT, Arora N, Gaur SN, Pasha S, Singh BP. Identification of a serine protease as a major allergen (Per a 10) of Periplaneta americana. Allergy. 2008;63:768–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grobe K, Pöppelmann M, Becker WM, Petersen A. Properties of group I allergens from grass pollen and their relation to cathepsin B, a member of the C1 family of cysteine proteinases. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:2083–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suck R, Petersen A, Hagen S, Cromwell O, Becker WM, Fiebig H. Complementary DNA cloning and expression of a newly recognized high molecular mass allergen phl p 13 from timothy grass pollen (Phleum pratense) Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:324–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibrahim ARN, Kawamoto S, Aki T, Shimada Y, Rikimaru S, Onishi N, Babiker EE, Oiso I, Hashimoto K, Hayashi T, Ono K. Molecular cloning and immunochemical characterization of a novel major Japanese cedar pollen allergen belonging to the aspartic protease family. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;152:207–18. doi: 10.1159/000283026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sokol CL, Barton GM, Farr AG, Medzhitov R. A mechanism for the initiation of allergen-induced T helper type 2 responses. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:310–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunningham PT, Elliot CE, Lenzo JC, Jarnicki AG, Larcombe AN, Zosky GR, Holt PG, Thomas WR. Sensitizing and Th2 adjuvant activity of cysteine protease allergens. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;158:347–58. doi: 10.1159/000334280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman MD, Wünschmann S, Pomés A. Proteases as Th2 adjuvants. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2007;7:363–7. doi: 10.1007/s11882-007-0055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt D, Verdaguer J, Averill N, Santamaria P. A Mechanism for the Major Histocompatibility Complex-linked Resistance to Autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1059–1075. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller AC, Mucida D, Gomes E, Faquim-Mauro E, Faria AMC, Rodriguez D, Russo M. Hierarchical suppression of asthma-like responses by mucosal tolerance. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:283–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollingsworth JW, Cook DN, Brass DM, Walker JKL, Morgan DL, Foster WM, Schwartz DA. The role of Toll-like receptor 4 in environmental airway injury in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:126–32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200311-1499OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitehead GS, Walker JKL, Berman KG, Foster WM, Schwartz DA. Allergen-induced airway disease is mouse strain dependent. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L32–42. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00390.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russo M, Nahori MA, Lefort J, Gomes E, de Castro Keller A, Rodriguez D, Ribeiro OG, Adriouch S, Gallois V, de Faria AM, Vargaftig BB. Suppression of asthma-like responses in different mouse strains by oral tolerance. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:518–26. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.5.4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramos RN, Chin LS, Dos Santos APSa, Bergami-Santos PC, Laginha F, Barbuto JAM. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells from breast cancer patients are biased to induce CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:1–10. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0112048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bortolatto J, Borducchi E, Rodriguez D, Keller AC, Faquim-Mauro E, Bortoluci KR, Mucida D, Gomes E, Christ A, Schnyder-Candrian S, Schnyder B, Ryffel B, Russo M. Toll-like receptor 4 agonists adsorbed to aluminium hydroxide adjuvant attenuate ovalbumin-specific allergic airway disease: role of MyD88 adaptor molecule and interleukin-12/interferon-gamma axis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1668–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soto-Mera MT, López-Rico MR, Filgueira JF, Villamil E, Cidrás R. Occupational allergy to papain. Allergy. 2000;55:983–4. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herxheimer H. The late bronchial reaction in induced asthma. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1952;3:323–8. doi: 10.1159/000227979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shpacovitch V, Feld M, Bunnett NW, Steinhoff M. Protease-activated receptors: novel PARtners in innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:541–50. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidlin F, Amadesi S, Dabbagh K, Lewis DE, Knott P, Bunnett NW, Gater PR, Geppetti P, Bertrand C, Stevens ME. Protease-activated receptor 2 mediates eosinophil infiltration and hyperreactivity in allergic inflammation of the airway. J Immunol. 2002;169:5315–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kroeger KM, Sullivan BM, Locksley RM. IL-18 and IL-33 elicit Th2 cytokines from basophils via a MyD88- and p38alpha-dependent pathway. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:769–78. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0708452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hammad H, Chieppa M, Perros F, Willart AM, Germain RN, Lambrecht BN. House dust mite allergen induces asthma via Toll-like receptor 4 triggering of airway structural cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:410–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidt M, Raghavan B, Müller V, Vogl T, Fejer G, Tchaptchet S, Keck S, Kalis C, Nielsen PJ, Galanos C, Roth J, Skerra A, Martin SF, Freudenberg Ma, Goebeler M. Crucial role for human Toll-like receptor 4 in the development of contact allergy to nickel. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:814–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker JA, McKenzie AN. Development and function of group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Abt MC, Alenghat T, Ziegler CGK, Doering TA, Angelosanto JM, Laidlaw BJ, Yang CY, Sathaliyawala T, Kubota M, Turner D, Diamond JM, Goldrath AW, Farber DL, Collman RG, Wherry EJ, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat Immunol. 2011;12 doi: 10.1031/ni.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cocks TM, Moffatt JD. Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2) in the airways. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2001;14:183–91. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2001.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewkowich IP, Day SB, Ledford JR, Zhou P, Dienger K, Wills-Karp M, Page K. Protease-activated receptor 2 activation of myeloid dendritic cells regulates allergic airway inflammation. Respir Res. 2011;12:122. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saenz SA, Taylor BC, Artis D. Welcome to the neighborhood: epithelial cell-derived cytokines license innate and adaptive immune responses at mucosal sites. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:172–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klein Wolterink RGJ, Kleinjan A, van Nimwegen M, Bergen I, de Bruijn M, Levani Y, Hendriks RW. Pulmonary innate lymphoid cells are major producers of IL-5 and IL-13 in murine models of allergic asthma. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1106–16. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaiss DM, Yang L, Shah PR, Kobie JJ, Urban JF, Mosmann TR. Amphiregulin, a TH2 cytokine enhancing resistance to nematodes. Science. 2006;314:1746. doi: 10.1126/science.1133715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tamachi T, Maezawa Y, Ikeda K, Kagami SI, Hatano M, Seto Y, Suto A, Suzuki K, Watanabe N, Saito Y, Tokuhisa T, Iwamoto I, Nakajima H. IL-25 enhances allergic airway inflammation by amplifying a TH2 cell-dependent pathway in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:606–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hammad H, Plantinga M, Deswarte K, Pouliot P, Willart MaM, Kool M, Muskens F, Lambrecht BN. Inflammatory dendritic cells--not basophils--are necessary and sufficient for induction of Th2 immunity to inhaled house dust mite allergen. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2097–111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumamoto Y, Linehan M, Weinstein JS, Laidlaw BJ, Craft JE, Iwasaki A. CD301b+ dermal dendritic cells drive T helper 2 cell-mediated immunity. Immunity. 2013;39:733–43. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao Y, Nish SA, Jiang R, Hou L, Licona-Limón P, Weinstein JS, Zhao H, Medzhitov R. Control of T helper 2 responses by transcription factor IRF4-dependent dendritic cells. Immunity. 2013;39:722–32. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenstein RK, Bezbradica JS, Yu S, Medzhitov R. Signaling pathways activated by a protease allergen in basophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E4963–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418959111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spooner CJ, Lesch J, Yan D, Khan AA, Abbas A, Ramirez-Carrozzi V, Zhou M, Soriano R, Eastham-Anderson J, Diehl L, Lee WP, Modrusan Z, Pappu R, Xu M, De Voss J, Singh H. Specification of type 2 innate lymphocytes by the transcriptional determinant Gfi1. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1229–36. doi: 10.1038/ni.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Townsend MJ, Fallon PG, Matthews DJ, Jolin HE, McKenzie ANJ. T1/ST2-deficient mice demonstrate the importance of T1/ST2 in developing primary T helper cell type 2 responses. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1069–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kakkar R, Lee RT. The IL-33/ST2 pathway: therapeutic target and novel biomarker. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:827–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wikstrom ME, Batanero E, Smith M, Thomas JA, von Garnier C, Holt PG, Stumbles PA. Influence of mucosal adjuvants on antigen passage and CD4+ T cell activation during the primary response to airborne allergen. J Immunol. 2006;177:913–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pepys J, Longbottom JL, Hargreave FE, Faux J. Allergic reactions of the lungs to enzymes of Bacillus subtilis. Lancet. 1969;1:1181–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)92166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flindt ML. Pulmonary disease due to inhalation of derivatives of Bacillus subtilis containing proteolytic enzyme. Lancet. 1969;1:1177–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)92165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blaikie L, Basketter D. Experience with a Mouse Intranasal Test for the Predictive Identification of Respiratory Sensitization Potential of Proteins. Food Chem Toxicol. 1999;37:889–896. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(99)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robinson MK, Babcock LS, Horn PA, Kawabata TT. Specific antibody responses to subtilisin Carlsberg (Alcalase) in mice: development of an intranasal exposure model. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1996;34:15–24. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarlo K, Ritz HL, Fletcher ER, Schrotel KR, Clark ED. Proteolytic detergent enzymes enhance the allergic antibody responses of guinea pigs to nonproteolytic detergent enzymes in a mixture : Implications for occupational exposure. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:480–487. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kawabata TT, Babcock LS, Horn PA. Specific IgE and IgG1 responses to subtilisin Carlsberg (Alcalase) in mice: development of an intratracheal exposure model. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1996;29:238–43. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shakib F, Ghaemmaghami AM, Sewell HF. The molecular basis of allergenicity. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:633–42. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wills-Karp M, Nathan A, Page K, Karp CL. New insights into innate immune mechanisms underlying allergenicity. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3:104–10. doi: 10.1038/mi.2009.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jacquet A. Interactions of airway epithelium with protease allergens in the allergic response. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:305–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takai T, Ikeda S. Barrier dysfunction caused by environmental proteases in the pathogenesis of allergic diseases. Allergol Int. 2011;60:25–35. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.10-RAI-0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Page K, Ledford JR, Zhou P, Dienger K, Wills-Karp M. Mucosal sensitization to German cockroach involves protease-activated receptor-2. Respir Res. 2010;11:62. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kato T, Takai T, Fujimura T, Matsuoka H, Ogawa T, Murayama K, Ishii a, Ikeda S, Okumura K, Ogawa H. Mite serine protease activates protease-activated receptor-2 and induces cytokine release in human keratinocytes. Allergy. 2009;64:1366–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kouzaki H, O'Grady SM, Lawrence CB, Kita H. Proteases induce production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin by airway epithelial cells through protease-activated receptor-2. J Immunol. 2009;183:1427–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miazgowicz MM, Headley MB, Larson RP, Ziegler SF. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin and the pathophysiology of atopic disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2009;5:547–556. doi: 10.1586/eci.09.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilson SR, Thé L, Batia LM, Beattie K, Katibah GE, McClain SP, Pellegrino M, Estandian DM, Bautista DM. The Epithelial Cell-Derived Atopic Dermatitis Cytokine TSLP Activates Neurons to Induce Itch. Cell. 2013;155:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goel C, Govindaraj D, Singh BP, Farooque a, Kalra N, Arora N. Serine protease Per a 10 from Periplaneta americana bias dendritic cells towards type 2 by upregulating CD86 and low IL-12 secretions. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:412–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Su Z, Lin J, Lu F, Zhang X, Zhang L. Potential autocrine regulation of interleukin-33/ST2 signaling of dendritic cells in allergic inflammation. Mucosal …. 2013;6:921–930. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leyva-Castillo JM, Hener P, Michea P, Karasuyama H, Chan S, Soumelis V, Li M. Skin thymic stromal lymphopoietin initiates Th2 responses through an orchestrated immune cascade. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2847. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Halim T, MacLaren A, Romanish M. Retinoic-Acid-Receptor-Related Orphan Nuclear Receptor Alpha Is Required for Natural Helper Cell Development and Allergic Inflammation. Immunity. 2012;2:463–474. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oliphant CJ, Barlow JL, McKenzie ANJ. Insights into the initiation of type 2 immune responses. Immunology. 2011;134:378–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scalfone LK, Nel HJ, Gagliardo LF, Cameron JL, Al-Shokri S, Leifer Ca, Fallon PG, Appleton Ja. Participation of MyD88 and interleukin-33 as innate drivers of Th2 immunity to Trichinella spiralis. Infect Immun. 2013;81:1354–63. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01307-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nhu QM, Shirey K, Teijaro JR, Farber DL, Netzel-Arnett S, Antalis TM, Fasano A, Vogel SN. Novel signaling interactions between proteinase-activated receptor 2 and Toll-like receptors in vitro and in vivo. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3:29–39. doi: 10.1038/mi.2009.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Post S, Heijink IH, Petersen AH, de Bruin HG, van Oosterhout AJM, Nawijn MC. Protease-activated receptor-2 activation contributes to house dust mite-induced IgE responses in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Willart MaM, Deswarte K, Pouliot P, Braun H, Beyaert R, Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. Interleukin-1α controls allergic sensitization to inhaled house dust mite via the epithelial release of GM-CSF and IL-33. J Exp Med. 2012 doi: 10.1084/jem.20112691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.