Abstract

The GNAS complex locus encodes the alpha-subunit of the stimulatory G protein (Gsα), a ubiquitous signaling protein mediating the actions of many hormones, neurotransmitters, and paracrine/aurocrine factors via generation of the second messenger cAMP. GNAS gives rise to other gene products, most of which exhibit exclusively monoallelic expression. In contrast, Gsα is expressed biallelically in most tissues; however, paternal Gsα expression is silenced in a small number of tissues through as-yet-poorly understood mechanisms that involve differential methylation within GNAS. Gsα-coding GNAS mutations that lead to diminished Gsα expression and/or function result in Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy (AHO) with or without hormone resistance, i.e. pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ia/Ic and pseudo-pseudohypoparathryodism, respectively. Microdeletions that alter GNAS methylation and, thereby, diminish Gsα expression in tissues in which the paternal Gsα allele is normally silenced also cause hormone resistance, which occurs typically in the absence of AHO, a disorder termed pseudohypoparathyroidism type-Ib. Mutations of GNAS that cause constitutive Gsα signaling are found in patients with McCune-Albright syndrome, fibrous dysplasia of bone, and different endocrine and non-endocrine tumors. Clinical features of these diseases depend significantly on the parental allelic origin of the GNAS mutation, reflecting the tissue-specific paternal Gsα silencing. In this article, we review the pathogenesis and the phenotypes of these human diseases.

Keywords: GNAS, pseudohypoparathyroidism, Gsα, alpha-subunit of the stimulatory G protein

The GNAS complex locus

The GNAS gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 20 in humans [1], gives rise to multiple gene products, including transcripts that encode the alpha-subunit of the stimulatory guanine nucleotide-binding protein (Gsα), extra-large Gsα (XLαs), and neuroendocrine secretory protein 55 (NESP55) [2–5] (Fig. 1). Two additional transcripts are also derived from GNAS: the A/B (also referred to as 1A or 1’) and the GNAS-AS1 transcripts. These are non-coding, although some evidence suggests that A/B could be translated [6]. Gsα is encoded by exons 1–13, while NESP55, XLαs, and A/B individually contain their own unique first exons that splice onto exon 2–13 of GNAS [2–5]. The GNAS-AS1 transcript, on the other hand, is derived from the antisense strand and traverses the promoter and the first exon of NESP55 [7, 8]. The mature GNAS-AS1 transcript is spliced but is subject to alternative splicing. Likewise, most of the sense transcripts are subject to alternative splicing, such as one that leads to the exclusion or the inclusion of exon 3, but the significance of these additional variants remains poorly understood. The transcriptional and splicing profiles of GNAS have been reviewed comprehensively in references 10, 11, and 12.

Figure 1. Multiple imprinted sense and antisense transcripts from the GNAS complex locus.

Exons 1–13 encode Gsα, which is biallelic in most tissues; however, paternal Gsα allele is silenced in certain tissues (dotted arrow). Several other transcripts arise from differentially methylated promoters, including the maternally expressed NESP55 and the paternally expressed XLαs and A/B (also referred to as 1A or 1’). All of these transcripts use individual first exons that splice onto exons 2–13 of GNAS. Another non-coding transcript is also derived from the paternal GNAS allele, but this transcript is made from the antisense strand (GNAS-AS1 transcript, also referred to as Nespas in mice). Boxes and connecting lines depict exons and introns, respectively. Maternal (mat) and paternal (pat) GNAS products are illustrated above and below the gene structure, respectively, with splicing patterns indicated by broken lines. “+” indicates methylated promoters either on the paternal allele (NESP55) or the maternal allele (XLαs, A/B, GNAS-AS1 exon 1). Arrows indicate direction of transcription. The figure is not drawn to scale.

Multiple differentially methylated regions (DMR) are present within the GNAS locus, encompassing the promoters of the different transcripts. DNA methylation is a mechanism regulating gene expression, and this epigenetic modification often leads to or associated with repressed promoter activity in an allele specific manner [9]. As in many other genomic loci, the GNAS promoter located in the methylated allele is silenced, such that while the XLαs, A/B and GNAS-AS1 transcripts are exclusively paternally expressed, the NESP55 transcript is maternally expressed [7, 8, 10–14] (Fig. 1). The genomic region comprising the putative promoter of Gsα do not show any methylation, and the Gsα transcript is biallelically expressed in most tissues. However, based on data from mice and humans, paternal Gsα expression is silenced in some tissues, including proximal renal tubules, neonatal brown adipose tissue (BAT), thyroid, gonads, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and pituitary [15–21]. Mechanisms underlying the tissue specific maternal expression of Gsα are poorly defined. Yet, it is clear that this epigenetic event contributes greatly to the parent-of-origin specific phenotypic variability of GNAS mutations (see below).

Cellular action of Gsα

Similar to other G alpha subunits, Gsα exists in a GDP-bound form at the basal state as part of a heterotrimeric complex. Agonist-activation of a Gsα-coupled heptahelical transmembrane receptor, such as the beta-adrenergic receptor or the receptor for parathyroid hormone (PTHR), induces a GDP-GTP exchange, thus leading to the dissociation of Gsα from Gβγ subunits. The GTP-bound Gsα is able to stimulate different effectors and thereby initiates various responses depending on the cellular context. The most extensively investigated effector stimulated by Gsα is adeynylyl cylase, which catalyzes the conversion of ATP into the second messenger cAMP. Gsα is a GTP hydrolase and this activity ensures that the activation of Gsα is short-lived by converting the latter back into its GDP-bound state, which then reassembles with Gβγ and becomes inactive until the cycle is reinitiated by an activated heptahelical receptor. Primary action of Gsα takes place at the plasma membrane. The membrane localization of Gsα depends on palmitoylation of an amino-terminal cysteine residue and its association with the Gβγ subunits. Upon activation, Gsα undergoes depalmitoylation, in addition to dissociating from Gβγ, and, thus, localizes to the cytosol.. The activation-induced subcellular redistribution of Gsα is another regulatory mechanism that limits Gsα signaling. Mechanisms and structural features of Gsα activation, along with the activation of other heterotrimeric G proteins, are reveiewed in detail elsewhere [22, 23].

Genetic disorders resulting from GNAS mutations

Inactivating mutations in Gsα-coding GNAS exons

PHP-Ia/PPHP and PHP-Ic

Germline or somatic alterations affecting the GNAS complex locus are responsible for several disorders. Heterozygous inactivating mutations in Gsα-coding GNAS exons cause Albright’s Hereditary Osteodystrophy (AHO), a constellation of features described originally by Fuller Albright and colleagues [24], including obesity with round face, short stature, brachydactyly, subcutaneous ossification, and mental retardation (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Certain patients with AHO and inactivating Gsα mutations also present with end-organ resistance to the actions of parathyroid hormone (PTH), a disorder called pseudohypoparathyroidism type-Ia (PHP-Ia). The classical feature of PHP-Ia, as well as other subtypes of PHP type-I, is a failure to increase urinary cAMP and urinary phosphate excretion in response to exogenous PTH administration [25]. This finding reflects PTH resistance at renal proximal tubules, in which PTH normally inhibits the reabsorption of phosphate and induces the expression of 25-dihydroxyvitamin D 1-alpha-hydroxylase (Cyp27b1) mRNA via cAMP-dependent cellular mechanisms. Of note, PHP type II (PHP-II) is characterized by normal nephrogenous cAMP generation with impaired urinary excretion of phosphate to exogenous PTH administration [26].

Figure 2. Genetic defects underlying the different GNAS-related disorders.

Mutations scattered through all Gsα-coding GNAS exons cause AHO (Albrigh’s hereditary osteodystrophy) with or without hormone resistance, i.e. pseudohypoparathyroidism (PHP)-Ia, PHP-Ic, pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism (PPHP), or progressive ossesous heteroplasia (POH). Maternal STX16 deletions cause isolated A/B loss of methylation; maternal deletion of NESP55 leads to isolated A/B loss of methylation with hemizygosity in NESP55. Maternal deletions affecting GNAS-AS1 (AS) exons 3 and 4 result in a loss of methylation at all maternal GNAS imprints. Sporadic PHP-Ib cases show loss of methylation at exon XL, the promoter of GNAS-AS1, and exon A/B, and a gain of methylation at exon NESP55, but the genetic defect is unknown except for paternal uniparental disomy involving chromosome 20q. Missense mutations of residues Arg201 and Gln227 cause McCune-Albright Syndrome (MAS) and fibrous dysplasia of bone (FD) and are found in various endocrine and non-endocrine tumors. Boxes and connecting lines depict exons and introns, respectively. Maternal (mat) and paternal (pat) GNAS products are indicated by their direction of transcription. Arrows indicate direction of transcription; dotted arrow is used to indicate the tissue-specific paternal silencing of Gsα. The figure is not drawn to scale.

Table 1.

The main disease subtypes caused by inactivating GNAS mutations and impaired Gsα function

| Genetic Defect |

Parental origin |

PTH resistance |

Additional hormone resistance |

#AHO features |

Urinary cAMP and phosphate to PTH |

Erythrocyte Gsα activity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHP Ia | Gsα coding | Maternal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Blunted | Reduced |

| PHP Ic | Gsα coding | Maternal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Blunted | Normal*** |

| PPHP | Gsα coding | Paternal | No | No | Yes | Normal | Reduced |

| POH* | Gsα coding | Paternal | No | No | No | Normal | Reduced |

| PHP Ib** | Microdeletions (STX16 or GNAS NESP55/AS) |

Maternal | Yes | No | No | Blunted | Normal |

Described AHO features are obesity, round face, short stature, brachydactyly, subcutaneous ossification and mental retardation. Please note that obesity and mental retardation are not obvious features of paternal mutations (PPHP).

POH patients sometimes have hormone resistance and/or AHO features; PTH-induced urinary excretion of cAMP and phosphate has been directly measured in few cases, but in most cases, these are predicted to be normal because of the paternal origin of the mutations.

The genetic defects alter the differential methylation status of GNAS; some patients additionally show mild TSH resistance; in several cases AHO features have been reported; a recent study showed mildly diminished erythrocyte Gsα activity in a series of patients with GNAS methylation defects.

In cases caused by GNAS mutations, Gsα coupling to receptors are impaired, leading to an apparently normal Gsα activity measurement when stimulation is carried out by using direct Gsα activators

Since Gsα signaling and cAMP production play important roles in the actions of a variety of hormones, resistance to additional hormones including thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH), and gonadotropins can also be observed in some patients with PHP-Ia, leading to hypothyroidism, growth hormone deficiency, and hypogonadism [27, 28]. Hypothyroidism could be the first clinical manifestation of PHP-Ia, as early as neonatal period, detected at screening for congenital hypothyroidism; however, the diagnosis of PHP-Ia is usually established when hypocalcemia and elevated PTH have been detected, which often becomes manifest during early childhood [17–19, 27–29].

The heterozygous mutations in Gsα-coding GNAS exons are found not only in patients with PHP-Ia but also in patients who present with AHO features in the absence of hormone resistance, referred to as pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism (PPHP) [30]. This disorder is often found in the same kindreds with PHP-Ia, but the two disorders are never present in the same sibship [31, 32]. PPHP develops when a Gsα mutation is inherited from the father, while PHP-Ia develops upon maternal transmission of the same mutation [31, 32]. This parent-of-origin specific mode of inheritance for hormone resistance could be explained by the tissue-specific paternal silencing of Gsα. Since the paternal allele is already silenced, an inactivating mutation on the maternal allele leads to a dramatic reduction in Gsα expression/activity in those tissues. In contrast, the same mutation does not lead to a change in Gsα expression/activity when located on the paternal allele. Thus, hormone resistance occurs only in those tissues in which paternal Gsα is silenced, while hormone responsiveness is seemingly normal in tissues in which Gsα expression is biallelic (despite the 50% reduction in Gsα activity) [15, 17–19, 25, 27–29]. For example, PTH actions in the proximal tubule are impaired, while vasopressin actions in the collecting duct are normal, consistent with the presence and absence of paternal Gsα silencing in those tissues, respectively [15, 25, 33]. Note, however, that evidence for subclinical PTH resistance, TSH resistance, and subnormal GH stimulation response have been detected in few cases with paternally inherited Gsα-coding GNAS mutations [34–39]. It remains unclear whether the biochemical alterations observed in those rare cases reflect mild hormone resistance resulting from paternal Gsα loss or unrelated factors.

As indicated above, PTH resistance in PHP-Ia typically develops after infancy and during early childhood. The latency in the development of PTH resistance has been experimentally demonstrated in mice heterozygous for maternal ablation of Gsα [40]. In fact, it correlates well with the finding that the paternal Gsα silencing is established gradually after early postnatal development in mouse renal proximal tubules [40]. Further studies are needed, however, to understand whether the delay in the establishment of paternal Gsα silencing directly contributes to the latency of PTH resistance, as other possibilities exist, including nutritional factors and the involvement of Gsα-independent signaling pathways. It is also necessary to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the spatiotemporal regulation of paternal Gsα silencing.

Gsα is expressed biallelically in most tissues, such as lymphocytes, adrenal, white adipose tissue, bone and growth plate chondrocytes [15, 41, 42]. AHO features are thought to develop due to Gsα haploinsufficiency in those tissues. For example, heterozygous ablation of Gsα in mouse growth plate chondrocytes results in accelerated differentiation into hypertrophy regardless of the parental origin of this genetic manipulation [42], and this is consistent with the bracydactyly, advanced bone age, and short final height despite the absence of pronounced short sature during childhood. Nonetheless, recent data from human studies have revealed that obesity and cognitive impairment occur predominantly in patients with PHP-Ia rather than PPHP [43, 44]. These findings are consistent with the paternal silencing of Gsα in certain parts of the brain [20].

Since exons 2–13 of GNAS are shared by XLαs, NESP55 and A/B, mutations in those exons lead to deficiency of not ony Gsα but also these other products; however, the phenotypes resulting from the deficiency of each of these GNAS products are unclear. One recent study showed that patients with PPHP have lower birth weights than PHP-Ia cases, and that those carrying mutations in exons 2–13 are even smaller at birth than those carrying exon 1 mutations, suggesting that the deficiency of a paternally expressed GNAS product, such as XLαs, contributes to this phenotype [45]. Accordingly, the paternal ablation of XLαs in mice leads to low birth weight [46, 47].

The 50% reduction of Gsα activity in patients with inactivating GNAS mutations can be utilized as a diagnostic test. Although this test is not extensively used in practice, it has been effectively employed in making the precise diagnosis of the PHP subtype (see below) [34, 48). Gsα activity is measured in patient-derived erythrocytes, which are used to complement membranes from turkey erythrocytes or S49 murine lymphoma cell membranes that lack endogenous Gsα activity [49, 50]. A single case with a compound heterozygous mutation having 10–20% Gsα activity has been reported [49]; however, no homozygous mutations with completely absent Gsα activity has yet been described in humans. Homozygous mutations could be incompatible with life, since embryonic lethality was observed in mice with homozygous ablation of Gnas [15, 52, 53].

A normal erythrocyte Gsα activity in the presence of typical clinical features of PHP-Ia is described as PHP-Ic [27]. In several cases with PHP-Ic, Gsα mutants have been identified, which are able to stimulate adenylyl cyclase but defective in receptor coupling. In those cases, Gsα activity could be measured as normal when the erythrocyte Gsα bioactivity assay is performed by using direct stimulators of Gsα activity, such as a GTP analog, rather than a receptor agonist. The identified Gsα mutations are located near the C-terminal end of the Gsα molecule, consistent with the importance of this region in receptor interactions [54, 55].

GNAS mutations identified thus far are listed in different publically available databases (see, for example, www.genecards.org). In general, genotype-phenotype correlation does not exist in diseases caused by inactivating GNAS mutations. However, a temperature sensitive Gsα mutant (A366S) that causes testotoxicosis due to constitutive activity at the lower temperature of the testes, but instability at body temperature, has been described in two boys [56, 57]. Constitutive activity of the Gsα-A366S mutant results from rapid GDP release. Additionally, an AVDT amino acid repeat insertion has been identified in two siblings, leading to an unstable, but overactive, Gsα mutant that causes transient neonatal diarrhea due to enhanced cAMP signaling in the gut [58]. This mutation also accelerates the GDP release, and in addition, prolongs the GTP hydrolase reaction, leading to constitutive activity. Because activation-induced Gsα depalmitoylation is inhibitied in the intestinal epithelium, the mutant associates with the plasma membrane more avidly than wild-type Gsα upon activation and, thereby, leads to elevated cAMP generation [58].

Progressive osseous heteroplasia

Progressive osseous heteroplasia (POH) is a rare manifestation of AHO characterized by severe heterotopic ossification, which, unlike those typically observed in AHO patients, is progressive and affects deep connective tissue and skeletal muscle [59]. Clinically, POH presents during infancy with dermal and subcutaneous ossifications and subsequently becomes invasive during childhood. Ossification of skeletal muscle and deep connective tissues (i.e. tendon, ligaments, fascia) can lead to ankylosis of affected joints and growth retardation of affected limbs later in life.

Although germline GNAS mutation are found in POH patients, features of AHO or hormone resistance are absent in most cases. Paternally inherited mutations have been detected in the great majority of cases [60], which is consistent with the absence of hormone resistance. The paternal inheritance of the mutations suggests the involvement of the deficiency of a paternally expressed GNAS product in the development of POH. However, although the same GNAS mutations have been identified in patients with POH, PHP-Ia, or PPHP, why some patients develop POH is unclear. Additionally, GNAS mutations could be detected only in the 64% of the peripheral leukocytes of patients with POH [61]. A recent study revealed that POH frequently follows dermomyotomes and shows lesional bias toward one side or the other and exclusive sidedness similar to the lesions observed in McCune Albright syndrome, which is caused by mosaic mutations of GNAS that cause constitutive Gsα activity (see below) [61]. Furthermore, introduction of a dominant negative Gsα mutant to chick embryo somite leads to a POH-like phenotype that shows exclusive sidedness [61]. These recent data provide new insights into the pathophysiology of POH, suggesting that the underlying cause of POH may be second-hit postzygotic mutations affecting tissues in patients with inherited heterozygous inactivating Gsα mutations. The activation of Hedgehog signaling has recently been documented in POH lesions [62]. It was also shown using mouse models that Gsα ablation causes heterotopic ossification through activation of Hedgehog signaling [62]. Future investigations using data from human samples will be important for better understanding of this disease and the underlying mechanisms.

Genetic mutations altering GNAS imprinting

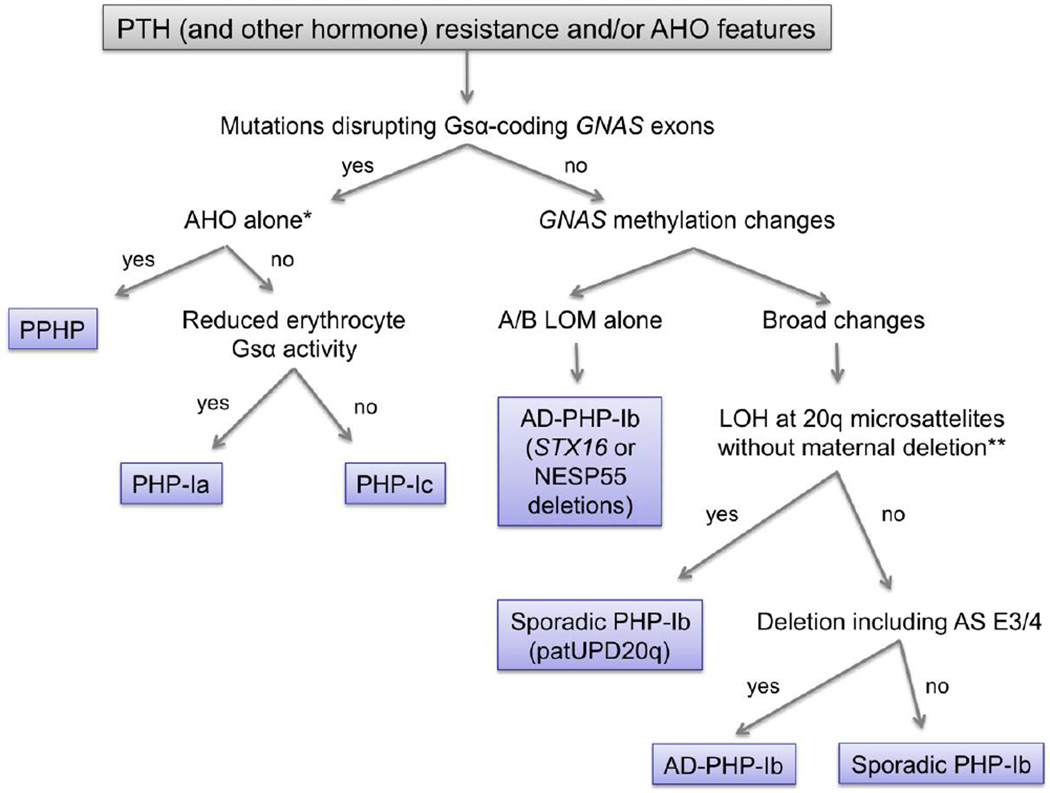

If the hormone resistance is confined to the actions of PTH in renal proximal tubules without any AHO features, the disorder is defined as PHP type Ib (PHP-Ib) [27, 28]. However, some patients with PHP-Ib show mildly elevated TSH levels, indicating TSH resistance [19]. Instead of Gsα-coding GNAS mutations, PHP-Ib patients have methylation defects in GNAS, including a loss of methylation at the A/B, GNAS-AS1, and XLαs DMRs and a gain of methylation at the NESP55 DMR [63, 64]. These methylation changes can be complete or partial, and involve some of the DMRs; however, the DMR comprising the promoter and the first exon of the A/B transcript is almost always affected. Although AHO features are typically absent in PHP-Ib, these have been detected in some patients who have epigenetic abnormalities of GNAS identical to those found in PHP-Ib [65–69]. Patients with PHP-Ib typically have normal erythrocyte Gsα activity, although a recent study demonstrated mild reduction of erythrocyte Gsα activity in PHP-Ib patients and more so in those with mild AHO featurs compared to normals [70]. Given that PHP-Ib patients have some additional hormone resistance (TSH resistance) and occasionally display AHO features, it appears that the main difference between PHP-Ib and PHP-Ia is the nature of the molecular defect. And if they have AHO features combined with PTH and TSH resistance, this clinical phenotype could lead to the diagnosis of PHP-Ic before molecular testing [48]. Thus, molecular and genetic testing for patients with AHO and/or evidence of hormone resistance is key to the correct establishment of the diagnosis and, therefore, effective genetic counseling. Figure 3 provides a basic scheme for diagnosing patients with AHO and/or hormone resistance, including the genetic defects associated with PHP-Ia, PHP-Ic, and PPHP, as well as with the different forms of PHP-Ib (see below).

Figure 3. A scheme of differential diagnosis for patients who present with AHO and/or hormone resistance.

DNA testing for GNAS mutations is conducted in a variety of commercial laboratories (see Genetic Testing Registry; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gtr/tests). PPHP, pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism; PHP, pseudohypoparathyroidism; AD-PHP-Ib, autosomal dominant pseudohypoparathyroidism; LOM, loss of methylation; LOH, loss of heterozygosity; patUPD20q, paternal uniparental disomy affecting the region of chromosome 20 that comprises GNAS; AS E3/4, GNAS-AS1 exons 3 and 4. *, if Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy (AHO) features include heterotopic ossification that invades the deep connective tissue and skeletal muscle, then the diagnosis is progressive osseous heteroplasia (POH). Note that patients with POH infrequently display other AHO features or hormone resistance. **, LOH can also be detected if there is a large deletion on the maternal allele that removes all the GNAS differentially methylated regions.

Autosomal dominant PHP-Ib

Most PHP-Ib cases are sporadic, but some cases with PHP-Ib are familial where the disorder is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner (AD-PHP-Ib). In AD-PHP-Ib families the hormone resistance is manifest only if the mutation is inherited from female obligate carriers, i.e. similar to the mode of inheritance of the hormone resistance in PHP-Ia [71]. In most AD-PHP-Ib cases, a loss of methylation at the exon A/B DMR is the only imprinting defect [63, 64]. Unlike in patients with PHP-Ia, PPHP, PHP-Ic, or POH, the genetic defects leading to these imprinting changes and PTH resistance are located outside the Gsα-coding GNAS exons (Fig. 2). Nearly all AD-PHP-Ib cases carry maternally inherited microdeletions in the neighboring STX16 gene encoding syntaxin-16 [72–74]. Most frequent deletion removes a 3-kb genomic region comprising exons 4–6, and the minimal overlap among these deletions includes STX16 exon 4 and flanking intronic regions [72–74]. In a single kindred with isolated loss of A/B methylation, however, a maternally inherited 19-kb deletion has been described, removing exon NESP55 and the upstream genomic region [75]. As the latter does not overlap with the deletions within STX16, it appears that two distinct regions are required for establishing the methylation imprint at the A/B DMR. Syntaxin-16 is a member of the syntaxin family of SNARE proteins [76]. Interestingly, STX16 is not an imprinted gene, and therefore, it is thought that the STX16 deletions disrupt a regulatory element of GNAS controlling the A/B methylation [72–74]. Targeted deletion of Stx16 exons 4–6 (i.e. equivalent to the recurrent 3-kb deletion in humans), however, does not cause PTH resistance or Gnas methylation abnormalities in mice regardless of the parental origin of the targeted allele and even when the deletion is homozygous [77]. This finding not only supports the hypothesis that the hormonal and epigenetic defects in AD-PHP-Ib do not result from syntaxin-16 deficiency, but also indicates that the location of this putative cis-acting regulatory element of Gnas is different in humans and mice.

Few AD-PHP-Ib cases have been reported to have methylation defects in multiple GNAS DMRs. In three unrelated AD-PHP-Ib families, deletions of all or part of the NESP55 DMR have been identified, including exon NESP55 and exons 3 and 4 of the GNAS-AS1 transcript (Fig. 2) [78, 79]. In two families, the deletions are nearly identical and remove the entire NESP55 DMR [78] and, in the third family, GNAS-AS1 transcript exons 3 and 4 are deleted along with a significant portion of intron 2, while NESP55 is preserved [79]. The overlap among these deletions comprises GNAS-AS1 exons 3 and 4, thus pointing to a cis-acting element regulating the maternal GNAS methylation imprints. Maternal deletion of the entire Nesp55 DMR, leads in mice to loss of all maternal Gnas methylation imprints, leading to hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hyperparathyroidism, i.e. PHP, by increasing A/B (1A in mice) transcription and decreasing Gsα mRNA levels in kidney [80, 81]. Paternal inheritance of this genetic defect does not cause any methylation defects. In addition, studies in mice have shown that the Nesp55 transcription is necessary for the establishment of the downstream maternal methylation imprints [82]. It is thus possible that the maternal deletion of the NESP55 DMR in patients (and in mice) alters GNAS methylation in cis by disrupting NESP55 transcription.

The deletions in the NESP55 region do not yield any methylation changes following paternal transmission. However, paternal inheritance in one kindred, in whom the deletion encompassed GNAS-AS1 exons 3 and 4 but not exon NESP55, led to incomplete alterations of GNAS methylation [79]. Thus, this deletion is predicted to affect a cis-acting element regulating imprinting on both parental alelles of GNAS. The methylation changes included a partial loss of NESP55 methylation and a partial gain of A/B methylation. Since the latter is the opposite of what is detected in affected individuals who inherit the deletion from their mothers, PTH levels were analyzed in the three individuals with the paternal deletion and were found, in one out of three, to be reduced. The carrier also had elevated 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels, suggesting enhanced PTH sensitivity [79]. Thus, Gsα expression may be increased in the proximal tubule of that carrier (and perhaps in the other two) as a result of gain A/B methylation. Accordingly, mice with paternal deletion of the Nespas promoter show loss of Nesp55 methylation, a partial gain of A/B methylation, and increased Gsα levels in tissues in which the paternal Gsα allele is normally silenced [83]. The A/B transcription is predicted to diminish as a result of a gain of methylation in this region. Since this epigenetic change is associated with elevated Gsα expression, it is thus possible that the silencing of the paternal Gsα allele occurs, at least partly, through a mechanism involving transcriptional interference from the A/B transcript. Recent data from a different mouse model in which A/B transcription is prematurely terminated supports this hypothesis [84].

Sporadic PHP-Ib

Non-familial PHP cases with epigenetic changes involving multiple GNAS DMRs are defined as sporadic PHP-Ib patients [85]. No clinical differences have yet been identified between sporadic PHP-Ib and AD-PHP-Ib [86]. The methylation abnormalities in some sporadic PHP-Ib cases result from paternal uniparental disomy involving a part or whole of chromosome 20q [87–92]. This genetic aberration can be revealed by analyzing patient and parental DNA samples for microsatellites in this genomic region and by determinining whether the patient has a loss of heterozygosity in the absence of maternal deletion. The genetic cause or other mechanisms underlying the methylation abnormalities have yet to be identified in most patients. De novo single or multiple base pair changes, other than large deletions, in the NESP55/AS exon 3&4 locus could be a possible mechanism, as suggested previously [85]. However, not a single case transmitting sporadic PHP-Ib to the offspring has thus far been identified [87, 93]. Recently, small intronic deletions of 33 and 40 base pairs at the NESP55 and GNAS-AS1 regions have been detected in two different PHP-Ib cases, but their association with the disease remains questionable [94]. So far, these methylation changes could occur stochastically, or enverionmental factors during pre- or post-implantation period could alter methylation, since increased frequency of disorders related to imprinting defects such as, Silver-Russel Syndrome and Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome, have been detected in babies born from in vitro fertilization [95, 96]. Additionally, genetic defects in a trans-acting factor necessary for the maintenance of methylation at GNAS and, perhaps, some other imprinted loci are possible in sporadic cases that show various mutli-locus methylation defects. In fact, GNAS methylation abnormalities have been identified in certain other imprinting disorders in which methylation changes occur at other genomic loci [97, 98]. Moreover, methylation defects in the DLK1/GTL2 or the PEG1/MEST locus have been detected in few sporadic PHP-Ib cases [99]. The clinical significance of the loss of methylation at DLK1/ GTL2, detected in one sporadic PHP-Ib case, is unclear. On the other hand, the loss of methylation at PEG1/MEST, found in another sporadic PHP-Ib case, could underlie the increased body mass index in this patient [99]. This epigenetic defect is predicted to yield biallelic expression of PEG1/MEST, which could result in fetal overgrowth, considering that the loss of the paternally expressed PEG1/MEST gene causes embryonic growth retardation [100].

Diseases resulting from constitutive Gsα activity

McCune-Albright Syndrome

Inhibition of the intrinsic GTP hydrolase activity of Gsα lead to constitutive cAMP signaling owing to the prolonged existence of Gsα in its active GTP-bound state. Most important residues are Arg201 or Gln227 with respect to the GTP hydrolase activity [101], and missense mutations at these residues cause McCune-Albright syndrome (MAS) [102–104]. The patients are mosaic for the mutations, and it is postulated that the mutation is acquired during early embryonic development [105]. Germline gain-of-function mutations are presumed to be incompatible with life, since no patient with MAS inherited the disease to the offspring. However, germ-line transmission of a constitutively active Gsα mutant found in MAS patients have been recently reported in transgenic mice [106], questioning the validity of the hypothesis that the mutant cells can survive only in the presence of wild-type cells [105].

MAS is characterized by the classic triad of polyostatic fibrous dysplasia, café-au lait skin pigmentation with highly irregular borders, and peripheral precocious puberty [107, 108]. Additionally, hyperthyroidism, Cushing syndrome, and pituitary gigantism/acromegaly could be part of the clinical presentation of MAS if mutated cells are present in thyroid, adrenal and/or pituitary tissues. Renal phosphate wasting with or without rickets/osteomalacia and rarely other organ systems could be involved like liver, cardiac, parathyroid, pancreas. For an extensive review of organ and tissue-systems involved, see references [109, 110].

Skin and bone lesions are typically asymmetric and, the skin lesions show distribution of Blaschko’s lines and do not cross the midline. The severity of disease or involved tissues is directly correlated with extent of mosaism and, generally, extent of skin lesions. Fibrous dysplasia (FD) can involve single bone (monoostotic) or multiple bones (polyostotic) [111–113]. Only about 1% of the cases have precousios puberty with café-au-lait spots in the absence of FD, and FD is the most frequent finding in MAS. For that reason, most frequent presentation of MAS is FD with at least one of the described endocrine hyperfunctions and/or café-au-lait spots; however, almost any combinations of the findings are possible.

Increased Gsα signaling is the underlying cause of the organ and tissue defects in MAS. For example, Gsα plays a critical role in the commitment of bone marrow stromal cells into the osteoblastic lineage and their further differentiation [114]. Enhanced Gsα signaling and cAMP generation accelerate the osteogenic commitment of the stromal cells but inhibit their further differention into osteoblasts, thus resulting in the formation of fibrous dysplatic lesions consisting of fibrous cells that express early osteoblastic markers, such as alkaline phosphatase [115, 116]. Likewise, the skin lesions occur as a result of increased Gsα signaling, which normally mediates the action of alpha-MSH to stimulate melanin production [117].

Synthesis and secretion of the phosphaturic hormone fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23) from the dysplastic tissue is suggested to cause renal phosphate wasting in MAS [118]. Nevertheless, frank rickets is rarely seen in those patients [119]. Consistent with that observation, a study has shown that increased cAMP in FD alters the processing of the FGF23 protein by GALNT3 and furin and, thus, leads to elevated levels of the inactive C-terminal fragment of FGF23 [120]. The cause of increased FGF23 production in the fibrous tissue is currently unknown. Gsα mediated signaling, induced by PTH, have been shown to stimulate FGF23 transcription in osteoblast and osteocytes, suggesting that increased FGF23 in FD lesions may be a direct consequence of the constitutive cAMP signaling [121, 122]. However, it is possible that the elevated FGF23 is secondary to the aberrant differentiation of the stromal cells and/or mediated by some auotcrine/paracrine factors generated within the FD lesion.

The allelic origin of the postzygotically acquired Gsα mutation has an impact on the involvement of affected tissues. This is particularly true for GH secreting adenomas, reflecting the monoallelic expression of Gsα in the pituitary [21]. Accordingly, GH hypersecretion/acromegaly has been found only in those patients in whom the mutation is located on the maternal allele [123, 124]. In contrast, both maternal and paternal mutations can be present in affected thyroid or ovaries despite the predominant maternal expression of Gsα in those tissues, as well.

Endocrine and non-endocrine tumors

Somatic GNAS mutations that cause constitutive Gsα activity have also been detected in several endocrine and non-endocrine tumors, leading to the term “gsp oncogene” [101]. These tumors are typically well-differentiated, consistent with the role of cAMP signaling in both cell proliferation and differentiation. Constituvely activating Gsα mutations are found in about 40% of isolated GH secreting pituitary adenomas leading to acromegaly [101, 125]. Similar to the findings in MAS patients with GH excess, the activating mutation is almost always maternal [21, 123]. Moreover, the paternal silencing of Gsα is frequently lost in both gsp+ and gsp- somatotroph tumors [21], underscoring the importance of increased cAMP signaling in the pathogenesis of these tumors. The same constitutively activating Gsα mutations are also found in isolated tumors of tissues that are often affected in MAS patients, such as thyroid and adrenal cortex [126]. In addition, a wide variety of other benign or malignant tumors have been shown to carry activating GNAS mutations, including inflammatory hepatic tumors, renal clear cell carcinoma, intraductal pancreatic mucinous cysts, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and colorectal tumors [127–130]. It remains to be determined whether the gsp is a driver mutation in these tumors. Since the tumors in MAS patients likely develop as a result of constituve Gs α activity, a careful analysis of those patients for the presence of atypical tumors will help determine the role of constitutive Gs α signaling in tumorigenesis.

The activating mutations are predicted to affect other imprinted GNAS products depending on whether the mutation is acquired on the maternal or the paternal allele. It is unclear whether altered activities of these additional GNAS products contribute to the phenotype. However, it is possible that constitutive XLαs activity is involved in the pathogenesis of MAS or the various tumors carrying those GNAS mutations, as XLαs has a stronger basal activity than Gsα and the same mutations lead to higher basal cAMP signaling when introduced into the XLαs backbone than into the Gsα backbone [131]. In fact, one study investigating the allelic origin of the mutations in MAS patients suggested that, in some patients, constitutive XLαs but not constitutive Gsα activity may drive the pathogenesis of thyroid overactivity and ovarian cysts [124]. Further investigations are necessary for understanding the involvement of XLαs or other GNAS products in the development of MAS findings or various tumors. Note that increased GNAS copy number is found in a number of different tumors, and that increased XLαs activity has been suggested to play a direct role in the pathogenesis of breast cancers in which chromosome 20q is amplified [132].

Summary

The imprinted GNAS complex locus, which gives rise to the ubiquitously expressed signaling protein Gsα and other imprinted gene products, is critical for the actions of many hormones and other endogenous molecules. Mutations that disrupt the expression or activity of Gsα lead to AHO and related diseases including the different subtypes of PHP type-I. Activating mutations, on the other hand, cause McCune-Albright syndrome and fibrous dysplasia of bone and are found in various tumors. Alterations in the activities of other GNAS products, particularly XLαs, could also contribute to the pathogenesis of these diseases.

Acknowledgments

The studies conducted in the laboratory of M.B. are funded in part by research grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (RO1 DK073911), the March of Dimes Foundation, and the Milton Fund.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

S Turan and M Bastepe both declare no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All studies by the authors involving animal and/or human subjects were performed after approval by the appropriate institutional review boards. When required, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

•• Of major importance

• Of importance

- 1.Blatt C, Eversole-Cire P, Cohn VH, et al. Chromosomal localization of genes encoding guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunits in mouse and human. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:7642–7646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kehlenbach RH, Matthey J, Huttner WB. XL alpha s is a new type of G protein. Nature. 1994;372:804–809. doi: 10.1038/372804a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ischia R, Lovisetti-Scamihorn P, Hogue-Angeletti R, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of NESP55, a novel chromogranin-like precursor of a peptide with 5-HT1B receptor antagonist activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11657–11662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishikawa Y, Bianchi C, Nadal-Ginard B, et al. Alternative promoter and 5’ exon generate a novel Gsα mRNA. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:8458–8462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swaroop A, Agarwal N, Gruen JR, et al. Differential expression of novel Gs alpha signal transduction protein cDNA species. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4725–4729. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.17.4725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puzhko S, Goodyer C, Kerachian M, et al. Parathyroid hormone signaling via G α s is selectively inhibited by an NH2-terminally truncated G α s: implications for pseudohypoparathyroidism. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2473–2485. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayward B, Bonthron D. An imprinted antisense transcript at the human GNAS1 locus. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:835–841. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.5.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wroe SF, Kelsey G, Skinner JA, et al. An imprinted transcript, antisense to Nesp, adds complexity to the cluster of imprinted genes at the mouse Gnas locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3342–3346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050015397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barlow DP, Bartolomei MS. Genomic imprinting in mammals. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014 Feb 1;6(2) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018382. pii: a018382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bastepe M. The GNAS Locus: Quintessential Complex Gene Encoding Gsalpha, XLalphas, and other Imprinted Transcripts. Curr Genomics. 2007;8:398–414. doi: 10.2174/138920207783406488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters J, Williamson CM. Control of imprinting at the Gnas cluster. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;626:16–26. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77576-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plagge A, Kelsey G, Germain-Lee EL. Physiological functions of the imprinted Gnas locus and its protein variants Galpha(s) and XLalpha(s) in human and mouse. J Endocrinol. 2008;196:193–214. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayward BE, Kamiya M, Strain L, et al. The human GNAS1 gene is imprinted and encodes distinct paternally and biallelically expressed G proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10038–10043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayward BE, Moran V, Strain L, et al. Bidirectional imprinting of a single gene: GNAS1 encodes maternally, paternally, and biallelically derived proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15475–15480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu S, Yu D, Lee E, Eckhaus M, et al. Variable and tissue-specific hormone resistance in heterotrimeric Gs protein alpha-subunit (Gsalpha) knockout mice is due to tissue-specific imprinting of the gsalpha gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8715–8720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williamson CM, Ball ST, Nottingham WT, et al. A cis-acting control region is required exclusively for the tissue-specific imprinting of Gnas. Nat Genet. 2004;36:894–899. doi: 10.1038/ng1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mantovani G, Ballare E, Giammona E, et al. The Gsalpha gene: Predominant maternal origin of transcription in human thyroid gland and gonads. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4736–4740. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Germain-Lee EL, Ding CL, Deng Z, et al. Paternal imprinting of Galpha(s) in the human thyroid as the basis of TSH resistance in pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1a. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:67–72. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00833-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J, Erlichman B, Weinstein LS. The stimulatory G protein alpha-subunit Gs alpha is imprinted in human thyroid glands: Implications for thyroid function in pseudohypoparathyroidism types 1A and 1B. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2003;88:4336–4341. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen M, Wang J, Dickerson KE, et al. Central nervous system imprinting of the G protein G(s)alpha and its role in metabolic regulation. Cell Metab. 2009;9:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayward B, Barlier A, Korbonits M, et al. Imprinting of the G(s)alpha gene GNAS1 in the pathogenesis of acromegaly. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:R31–R36. doi: 10.1172/JCI11887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cabrera-Vera TM, Vanhauwe J, Thomas TO, et al. Insights into G protein structure, function, and regulation. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:765–781. doi: 10.1210/er.2000-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marrari Y, Crouthamel M, Irannejad R, et al. Assembly and trafficking of heterotrimeric G proteins. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7665–7677. doi: 10.1021/bi700338m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albright F, Burnett CH, Smith PH, et al. Pseudohypoparathyroidism - An example of ‘Seabright-Bantam syndrome’. Endocrinology. 1942;30:922–932. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chase LR, Melson GL, Aurbach GD. Pseudohypoparathyroidism: Defective excretion of 3’,5’-AMP in response to parathyroid hormone. J Clin Invest. 1969;48:1832–1844. doi: 10.1172/JCI106149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drezner M, Neelon FA, Lebovitz HE. Pseudohypoparathyroidism type II: A possible defect in the reception of the cyclic AMP signal. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:1056–1060. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197311152892003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine MA. Pseudohypoparathyroidism; in. In: JP Bilezikian, LG Raisz, GA Rodan., editors. Principles of Bone Biology. New York, Academic Press: 2002. pp. 1137–1163. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinstein LS, Yu S, Warner DR, et al. Endocrine manifestations of stimulatory G protein alpha-subunit mutations and the role of genomic imprinting. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:675–705. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.5.0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gelfand IM, Eugster EA, DiMeglio LA. Presentation and clinical progression of pseudohypoparathyroidism with multi-hormone resistance and Albright hereditary osteodystrophy: a case series. J Pediatr. 2006;149:877–880. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albright F, Forbes AP, Henneman PH. Pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1952;65:337–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies AJ, Hughes HE. Imprinting in Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy. J Med Genet. 1993;30:101–103. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson LC, Oude-Luttikhuis MEM, Clayton PT, et al. Parental origin of Gsα gene mutations in Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy. J Med Genet. 1994;31:835–839. doi: 10.1136/jmg.31.11.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moses AM, Weinstock RS, Levine MA, et al. Evidence for normal antidiuretic responses to endogenous and exogenous arginine vasopressin in patients with guanine nucleotide- binding stimulatory protein-deficient pseudohypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;62:221–224. doi: 10.1210/jcem-62-1-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turan S, Thiele S, Tafaj O, et al. Evidence of hormone resistance in a pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism patient with a novel paternal mutation in GNAS. Bone. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.10.006. 02/2015; 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lau K, Willig RP, Hiort O, et al. Linear skin atrophy preceding calcinosis cutis in pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:646–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lebrun M, Richard N, Abeguilé G, et al. Progressive osseous heteroplasia: a model for the imprinting effects of GNAS inactivating mutations in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3028–3038. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuster V, Kress W, Kruse K. Paternal and maternal transmission of pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ia in a family with Albright hereditary osteodystrophy: no evidence of genomic imprinting. J Med Genet. 1994;31:84. doi: 10.1136/jmg.31.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aldred MA, Aftimos S, Hall C, et al. Constitutional deletion of chromosome 20q in two patients affected with albright hereditary osteodystrophy. Am J Med Genet. 2002;113:167–172. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ward S, Sugo E, Verge CF, et al. Three cases of osteoma cutis occurring in infancy. A brief overview of osteoma cutis and its association with pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:127–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2010.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Turan S, Fernandez-Rebollo E, Aydin C, et al. Postnatal establishment of allelic Gαs silencing as a plausible explanation for delayed onset of parathyroid hormone resistance owing to heterozygous Gαs disruption. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:749–760. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2070. In this experimental mice study, the authors showed that Gsα silencing in proximal renal tubule is established gradually after birth, and that PTH resistance in pseudohypoparathyroidism type-Ia develops mostly after infancy.

- 41.Mantovani G, Bondioni S, Locatelli M, et al. Biallelic expression of the Gsalpha gene in human bone and adipose tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:6316–6319. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bastepe M, Weinstein LS, Ogata N, et al. Stimulatory G protein directly regulates hypertrophic differentiation of growth plate cartilage in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14794–14799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405091101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mouallem M, Shaharabany M, Weintrob N, et al. Cognitive impairment is prevalent in pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ia, but not in pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism: possible cerebral imprinting of Gsalpha. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;68:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Long DN, McGuire S, Levine MA, et al. Body mass index differences in pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1a versus pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism may implicate paternal imprinting of Galpha(s) in the development of human obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1073–1079. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Richard N, Molin A, Coudray N, et al. Paternal GNAS mutations lead to severe intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) and provide evidence for a role of XL α s in fetal development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E1549–E1556. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1667. This paper showed that paternal GNAS mutations cause intra uterine growth retardation and that this phenotype is likely related to the deficiency of the paternally expressed GNAS product XLαs.

- 46.Plagge A, Gordon E, Dean W, et al. The imprinted signaling protein XL alpha s is required for postnatal adaptation to feeding. Nat Genet. 2004;36:818–826. doi: 10.1038/ng1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie T, Plagge A, Gavrilova O, et al. The alternative stimulatory G protein alpha-subunit XLalphas is a critical regulator of energy and glucose metabolism and sympathetic nerve activity in adult mice. 2006;281:18989–18999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511752200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brix B, Werner R, Staedt P, et al. Different pattern of epigenetic changes of the GNAS gene locus in patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ic confirm the heterogeneity of underlying pathomechanisms in this subgroup of pseudohypoparathyroidism and the demand for a new classification of GNAS-related disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E1564–E1570. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levine MA, Eil C, Downs RW, Jr, et al. Deficient guanine nucleotide regulatory unit activity in cultured fibroblast membranes from patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism type I. a cause of impaired synthesis of 3’,5’-cyclic AMP by intact and broken cells. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:316–324. doi: 10.1172/JCI110971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farfel Z, Brickman AS, Kaslow HR, et al. Defect of receptor-cyclase coupling protein in pseudohypoparathyroidism. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:237–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198007313030501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Freson K, Izzi B, Jaeken J, et al. Compound heterozygous mutations in the GNAS gene of a boy with morbid obesity, thyroid-stimulating hormone resistance, pseudohypoparathyroidism, and a prothrombotic state. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4844–4849. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Germain-Lee EL, Schwindinger W, Crane JL, Zewdu R, Zweifel LS, Wand G, Huso DL, Saji M, Ringel MD, Levine MA. A Mouse Model of Albright Hereditary Osteodystrophy Generated by Targeted Disruption of Exon 1 of the Gnas Gene. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4697–4709. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen M, Gavrilova O, Liu J, Xie T, Deng C, Nguyen AT, Nackers LM, Lorenzo J, Shen L, Weinstein LS. Alternative Gnas gene products have opposite effects on glucose and lipid metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7386–7391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408268102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Linglart A, Carel JC, Garabedian M, et al. GNAS1 Lesions in pseudohypoparathyroidism Ia and Ic: Genotype phenotype relationship and evidence of the maternal transmission of the hormonal resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:189–197. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.1.8133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thiele S, de Sanctis L, Werner R, et al. Functional characterization of GNAS mutations found in patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ic defines a new subgroup of pseudohypoparathyroidism affecting selectively Gsα-receptor interaction. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:653–660. doi: 10.1002/humu.21489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iiri T, Herzmark P, Nakamoto JM, et al. Rapid GDP release from Gs alpha in patients with gain and loss of endocrine function. Nature. 1994;371:164–168. doi: 10.1038/371164a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakamoto JM, Zimmerman D, Jones EA, et al. Concurrent hormone resistance (pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ia) and hormone independence (testotoxicosis) caused by a unique mutation in the G alpha s gene. Biochem Mol Med. 1996;58:18–24. doi: 10.1006/bmme.1996.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Makita N, Sato J, Rondard P, et al. Human G(salpha) mutant causes pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ia/neonatal diarrhea, a potential cell-specific role of the palmitoylation cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17424–17429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708561104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaplan FS, Craver R, MacEwen GD, et al. Progressive osseous heteroplasia: a distinct developmental disorder of heterotopic ossification. Two new case reports and follow-up of three previously reported Cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:425–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shore EM, Ahn J, Jan de Beur S, et al. Paternally inherited inactivating mutations of the GNAS1 gene in progressive osseous heteroplasia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:99–106. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cairns DM, Pignolo RJ, Uchimura T, et al. Somitic disruption of GNAS in chick embryos mimics progressive osseous heteroplasia. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3624–3633. doi: 10.1172/JCI69746. The data from this study implicated that severe disruption of Gsα leads to progressive osseous heteroplasia (POH) and that somatic second hit mutations in addition to germline GNAS mutations could lead to POH, thus explaining the phenotypic heterogeneity of heterozygous GNAS mutations.

- 62. Regard JB, Malhotra D, Gvozdenovic-Jeremic J, et al. Activation of Hedgehog signaling by loss of GNAS causes heterotopic ossification. Nat Med. 2013;19:1505–1512. doi: 10.1038/nm.3314. In this paper, it was shown that Hedgehog signaling is upregulated in progressive osseous heteroplasia, which is a result of Gsα deficiency caused by inactivating GNAS mutations. Additionally, genetically-mediated ectopic Hedgehog signaling is sufficient to induce heterotopic ossification in animal models, and the genetic or pharmacological inhibition of this signaling pathway reduces the severity of ectopic ossification.

- 63.Liu J, Litman D, Rosenberg MJ, et al. A GNAS1 imprinting defect in pseudohypoparathyroidism type IB. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1167–1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI10431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bastepe M, Pincus JE, Sugimoto T, et al. Positional dissociation between the genetic mutation responsible for pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib and the associated methylation defect at exon A/B: Evidence for a long-range regulatory element within the imprinted GNAS1 locus. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1231–1241. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.12.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Nanclares GP, Fernández-Rebollo E, Santin I, et al. Epigenetic defects of GNAS in patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism and mild features of Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2370–2373. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mariot V, Maupetit-Mehouas S, Sinding C, et al. A maternal epimutation of GNAS leads to Albright osteodys- trophy and parathyroid hormone resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:661–665. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Unluturk U, Harmanci A, Babaoglu M, et al. Molecular diagnosis and clinical characterization of pseudohypoparathyroidism type-Ib in a patient with mild Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy-like features, epileptic sei- zures, and defective renal handling of uric acid. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336:84–90. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31815b218f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mantovani G, de Sanctis L, Barbieri AM, et al. Pseudohypoparathyroidism and GNAS epigenetic defects: clinical evaluation of Albright hereditary osteodystrophy and molecular analysis in 40 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:651–658. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanchez J, Perera E, Jan de Beur S, et al. Madelung-like deformity in pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1b. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E1507–E1511. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zazo C, Thiele S, Martín C, et al. Gs α activity is reduced in erythrocyte membranes of patients with psedohypoparathyroidism due to epigenetic alterations at the GNAS locus. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1864–1870. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jüppner H, Schipani E, Bastepe M, et al. The gene responsible for pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib is paternally imprinted and maps in four unrelated kindreds to chromosome 20q13.3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11798–11803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bastepe M, Fröhlich LF, Hendy GN, et al. Autosomal dominant pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib is associated with a heterozygous microdeletion that likely disrupts a putative imprinting control element of GNAS. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1255–1263. doi: 10.1172/JCI19159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Linglart A, Gensure RC, Olney RC, et al. A novel STX16 deletion in autosomal dominant pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib redefines the boundaries of a cis-acting imprinting control element of GNAS. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:804–814. doi: 10.1086/429932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Elli FM, de Sanctis L, Peverelli E, et al. Autosomal dominant pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib: a novel inherited deletion ablating STX16 causes loss of imprinting at the A/B DMR. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E724–E728. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Richard N, Abeguilé G, Coudray N, et al. A New Deletion Ablating NESP55 Causes Loss of Maternal Imprint of A/B GNAS and Autosomal Dominant Pseudohypoparathyroidism Type Ib. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E863–E867. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2804. A novel deletion of 18,988 bp that removes NESP55 and a large upstream intronic region was discovered in a familial case with PHP-Ib in which maternal transmission causes loss of A/B methylation without affecting XL/AS imprinting; paternal transmission of the same deletion leads to no methylation anomalies. Taken together with the previously reported deletions, these findings indicate that isolated loss of A/B methylation can be caused by distinct, non-overlapping deletions in the STX16-GNAS region.

- 76.Tang BL, Low DY, Lee SS, et al. Molecular cloning and localization of human syntaxin 16, a member of the syntaxin family of SNARE proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;242:673–679. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fröhlich LF, Bastepe M, Ozturk D, et al. Lack of Gnas epigenetic changes and pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib in mice with targeted disruption of syntaxin-16. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2925–2935. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bastepe M, Fröhlich LF, Linglart A, et al. Deletion of the NESP55 differentially methylated region causes loss of maternal GNAS imprints and pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib. Nat Genet. 2005;37:25–27. doi: 10.1038/ng1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chillambhi S, Turan S, Hwang DY, et al. Deletion of the noncoding GNAS antisense transcript causes pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib and biparental defects of GNAS methylation in cis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3993–4002. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fröhlich LF, Mrakovcic M, Steinborn R, et al. Targeted deletion of the Nesp55 DMR defines another Gnas imprinting control region and provides a mouse model of autosomal dominant PHP-Ib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9275–9280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910224107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Fernández-Rebollo E, Maeda A, Reyes M, et al. Loss of XLαs (extra-large αs) imprinting results in early postnatal hypoglycemia and lethality in a mouse model of pseudohypoparathyroidism Ib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6638–6643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117608109. By showing improved survival upon normalization of XLαs expression, this study proved that the biallelic expression of XLαs is responsible for the early postnatal lethality in mice with deletion of the Nesp55 DMR. Surviving double-mutant animals had significantly reduced Gsα mRNA levels and showed hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, and elevated PTH levels, thus providing a viable model of human AD-PHP-Ib.).

- 82.Chotalia M, Smallwood SA, Ruf N, et al. Transcription is required for establishment of germline methylation marks at imprinted genes. Genes Dev. 2009;23:105–117. doi: 10.1101/gad.495809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Williamson CM, Turner MD, Ball ST, et al. Identification of an imprinting control region affecting the expression of all transcripts in the Gnas cluster. Nat Genet. 2006;38:350–355. doi: 10.1038/ng1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Eaton SA, Williamson CM, Ball ST, et al. New mutations at the imprinted Gnas cluster show gene dosage effects of Gs α in postnatal growth and implicate XL α s in bone and fat metabolism but not in suckling. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:1017–1029. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06174-11. This paper showed that the loss of ALEX is most likely responsible for the suckling defects in XLαs knockout pups. Additionally, increased metabolic rate and reductions in fat mass, leptin, and bone mineral density were attributed to the loss of XLαs. Moreover, the authors terminated the A/B transcript prematurely and thereby provided evidence that the tissue-specific paternal Gsα silencing results from transcriptional interference from the upstream A/B transcript.

- 85.Liu J, Nealon JG, Weinstein LS. Distinct patterns of abnormal GNAS imprinting in familial and sporadic pseudohypoparathyroidism type IB. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:95–102. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Linglart A, Bastepe M, Jüppner H. Similar clinical and laboratory findings in patients with symptomatic autosomal dominant and sporadic pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib despite different epigenetic changes at the GNAS locus. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007 Dec;67(6):822–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fernández-Rebollo E, Pérez de Nanclares G, Lecumberri B, et al. Exclusion of the GNAS locus in PHP-Ib patients with broad GNAS methylation changes: evidence for an autosomal recessive form of PHP-Ib? J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1854–1863. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bastepe M, Lane AH, Jüppner H. Paternal uniparental isodisomy of chromosome 20q--and the resulting changes in GNAS1 methylation--as a plausible cause of pseudohypoparathyroidism. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1283–1289. doi: 10.1086/320117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bastepe M, Altug-Teber O, Agarwal C, et al. Paternal uniparental isodisomy of the entire chromosome 20 as a molecular cause of pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib (PHP-Ib) Bone. 2011;48:659–662. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.10.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fernández-Rebollo E, Lecumberri B, Garin I, et al. New mechanisms involved in paternal 20q disomy associated with pseudohypoparathyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;163:953–962. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dixit A, Chandler KE, Lever M, et al. Pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1b due to paternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 20q. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E103–E108. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lecumberri B, Fernández-Rebollo E, Sentchordi L, et al. Coexistence of two different pseudohypoparathyroidism subtypes (Ia and Ib) in the same kindred with independent Gs{alpha} coding mutations and GNAS imprinting defects. J Med Genet. 2010;47:276–280. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.071001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cavaco BM, Tomaz RA, Fonseca F, et al. Clinical and genetic characterization of Portuguese patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib. Endocrine. 2010;37:408–414. doi: 10.1007/s12020-010-9321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rezwan FI, Poole RL, Prescott T, et al. Very small deletions within the NESP55 gene in pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1b. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014 Jul 9; doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vermeiden JP, Bernardus RE. Are imprinting disorders more prevalent after human in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection? Fertil Steril. 2013;99:642–651. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.01.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.DeBaun MR, Niemitz EL, Feinberg AP. Association of in vitro fertilization with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and epigenetic alterations of LIT1 and H19. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:156–160. doi: 10.1086/346031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bliek J, Verde G, Callaway J, et al. Hypomethylation at multiple maternally methylated imprinted regions including PLAGL1 and GNAS loci in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:611–619. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mackay DJ, Callaway JL, Marks SM, et al. Hypomethylation of multiple imprinted loci in individuals with transient neonatal diabetes is associated with mutations in ZFP57. Nat Genet. 2008;40:949–951. doi: 10.1038/ng.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Perez-Nanclares G, Romanelli V, Mayo S, et al. Spanish PHP Group: Detection of hypomethylation syndrome among patients with epigenetic alterations at the GNAS locus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1060–E1067. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1081. The authors found that multilocus imprinting defects, which has been described in some growth disorders, was rarely present in patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism Ib who had broad GNAS methylation defects and lacked any of the previously described microdeletions or paternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 20.

- 100.Lefebvre L, Viville S, Barton SC, et al. Abnormal maternal behaviour and growth retardation associated with loss of the imprinted gene Mest. Nat Genet. 1998;20:163–169. doi: 10.1038/2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Landis CA, Masters SB, Spada A, et al. GTPase inhibiting mutations activate the alpha chain of Gs and stimulate adenylyl cyclase in human pituitary tumours. Nature. 1989;34:692–696. doi: 10.1038/340692a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Weinstein LS, Shenker A, Gejman PV, et al. Activating mutations of the stimulatory G protein in the McCune-Albright syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1688–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112123252403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bianco P, Riminucci M, Majolagbe A, et al. Mutations of the GNAS1 gene, stromal cell dysfunction, and osteomalacic changes in non-McCune- Albright fibrous dysplasia of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:120–128. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Idowu BD, Al-Adnani M, O’Donnell P, et al. A sensitive mutation-specific screening technique for GNAS1 mutations in cases of fibrous dysplasia: the first report of a codon 227 mutation in bone. Histopathology. 2007;50:691–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Happle R. The McCune-Albright syndrome: a lethal gene surviving by mosaicism. Clin Genet. 1986;29:321–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1986.tb01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Saggio I, Remoli C, Spica E, et al. Constitutive Expression of Gs α (R201C) in Mice Produces a Heritable, Direct Replica of Human Fibrous Dysplasia Bone Pathology and Demonstrates Its Natural History. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:2357–2368. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.McCune DJ. Osteitis fibrosa cystica: the case of a nine-year-old girl who also exhibits precocious puberty, multiple pigmentation of the skin and hyperthyroidism. Am J Dis Child. 1936;52:743–744. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Albright F, Butler AM, Hampton AO, et al. Syndrome charac- terized by osteitis fibrosa disseminata, areas, of pigmentation, and endocrine dysfunction, with precocious puberty in females: report of 5 cases. N Engl J Med. 1937;216:727–746. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Spiegel AM, Weinstein LS. Inherited diseases involving g proteins and g protein-coupled receptors. Annu Rev Med. 2004;55:27–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Collins MT, Singer FR, Eugster E. McCune-Albright syndrome and the extraskeletal manifestations of fibrous dysplasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7(Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-7-S1-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lichtenstein LJH. Fibrous dysplasia of bone: a condition affecting one, several or many bones, graver cases of which may present abnormal pigmentation of skin, premature sexual development, hyperthyroidism or still other extraskeletal abnormalities. Arch Path. 1942;33:777–816. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bianco P, Robey PG, Wientroub S. Fibrous dysplasia. In: FH Glorieux, J Pettifor, H Juppner., editors. In Pediatric Bone: Biology and Disease. New York, NY: Academic Press, Elsevier; 2003. pp. 509–539. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Collins MT. Spectrum and natural history of fibrous dysplasia of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(Suppl 2):P199–P104. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.06s219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Wu JY, Aarnisalo P, Bastepe M, et al. Gs α enhances commitment of mesenchymal progenitors to the osteoblast lineage but restrains osteoblast differentiation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3492–3504. doi: 10.1172/JCI46406. The conditional Gsα knockout in osterix-expressing cells led to severe osteoporosis with fractures at birth, as a consequence of impaired bone formation related to rapid differentiation of mature osteoblasts leading to decreased osteoblast pool, rather than increased resorption. This study thus demonstrated the critical role of Gsα in temporal regulation of osteogenesis.

- 115.Riminucci M, Fisher LW, Shenker A, et al. Fibrous dysplasia of bone in the McCune-Albright syndrome: abnormalities in bone formation. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1587–1600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Marie PJ, de Pollak C, Chanson P, et al. Increased proliferation of osteoblastic cells expressing the activating Gs alpha mutation in monostotic and polyostotic fibrous dysplasia. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1059–1069. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cone RD, Lu D, Koppula S, et al. The melanocortin receptors: agonists, antagonists, and the hormonal control of pigmentation. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1996;51:287–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Riminucci M, Collins MT, Fedarko NS, et al. FGF-23 in fibrous dysplasia of bone and its relationship to renal phosphate wasting. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:683–692. doi: 10.1172/JCI18399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Collins MT, Chebli C, Jones J, et al. Renal phosphate wasting in fibrous dysplasia of bone is part of a generalized renal tubular dysfunction similar to that seen in tumor-induced osteomalacia. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:806–813. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.5.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bhattacharyya N, Wiench M, Dumitrescu C, et al. Mechanism of FGF23 processing in fibrous dysplasia. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:1132–1141. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rhee Y, Bivi N, Farrow E, et al. Parathyroid hormone receptor signaling in osteocytes increases the expression of fibroblast growth factor-23 in vitro and in vivo. Bone. 2011;49:636–643. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lavi-Moshayoff V, Wasserman G, Meir T, et al. PTH increases FGF23 gene expression and mediates the high-FGF23 levels of experimental kidney failure: a bone parathyroid feedback loop. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299:F882–F889. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00360.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mantovani G, Bondioni S, Lania AG, et al. Parental origin of Gsalpha mutations in the McCune-Albright syndrome and in isolated endocrine tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3007–3009. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mariot V, Wu JY, Aydin C, et al. Potent constitutive cyclic AMP-generating activity of XL α s implicates this imprinted GNAS product in the pathogenesis of McCune-Albright syndrome and fibrous dysplasia of bone. Bone. 2011;48:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lyons J, Landis CA, Harsh G, et al. Two G protein oncogenes in human endocrine tumors. Science. 1990;249:655–659. doi: 10.1126/science.2116665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Yoshimoto K, Iwahana H, Fukuda A, et al. Rare mutations of the Gs alpha subunit gene in human endocrine tumors. Mutation detection by polymerase chain reaction-primer-introduced restriction analysis. Cancer. 1993;72:1386–1393. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930815)72:4<1386::aid-cncr2820720439>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Nault JC, Fabre M, Couchy G, et al. GNAS-activating mutations define a rare subgroup of inflammatory liver tumors characterized by STAT3 activation. J Hepatol. 2012;56:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kalfa N, Lumbroso S, Boulle N, et al. Activating mutations of Gsalpha in kidney cancer. J Urol. 2006;176:891–895. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Wu J, Matthaei H, Maitra A, et al. Recurrent GNAS mutations define an unexpected pathway for pancreatic cyst development. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002543. 92ra66. The authors found that GNAS mutations were present in 66% of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN), one of the most common cystic neoplasms of the pancreas and a precursor to invasive adenocarcinoma. 96% of IPMN have either KRAS or GNAS mutations. This new finding could be a new hope for the management of pancreatic carcinoma.

- 130.Fecteau RE, Lutterbaugh J, Markowitz SD, et al. GNAS mutations identify a set of right-sided, RAS mutant, villous colon cancers. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Liu Z, Turan S, Wehbi VL, et al. Extra-long G α s variant XL α s protein escapes activation-induced subcellular redistribution and is able to provide sustained signaling. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:38558–38569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.240150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Garcia-Murillas I, Sharpe R, Pearson A, et al. An siRNA screen identifies the GNAS locus as a driver in 20q amplified breast cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33:2478–2486. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]