Abstract

DNA replication, damage response and repair require the coordinated action of multi-domain proteins operating within dynamic multi-protein machines that act upon the DNA substrate. These modular proteins contain flexible linkers of various lengths, which enable changes in the spatial distribution of the globular domains (architecture) that harbor their essential biochemical functions. This mobile architecture is uniquely suited to follow the evolving substrate landscape present over the course of the specific process performed by the multi-protein machinery. A fundamental advance in understanding of protein machinery is the realization of the pervasive role of dynamics. Not only is the machine undergoing dynamic transformations, but the proteins themselves are flexible and constantly adapting to the progression through the steps of the overall process. Within this dynamic context the activity of the constituent proteins must be coordinated, a role typically played by hub proteins. A number of important characteristics of modular proteins and concepts about the operation of dynamic machinery have been discerned. These provide the underlying basis for the action of the machinery that reads DNA, and responds to and repairs DNA damage. Here, we introduce a number of key characteristics and concepts, including the modularity of the proteins, linkage of weak binding sites, direct competition between sites, and allostery, using the well recognized hub protein replication protein A (RPA).

Keywords: DNA repair, DNA replication, multi-protein machinery, replication protein A, allostery, DNA mimicry, multivalent interactions

2. Introduction

Processing of DNA requires multiple biochemical steps and many more functions than can be incorporated into a single protein. All living organisms have therefore evolved to utilize the coordinated action of multi-protein machines to read, replicate and transcribe DNA, and respond to and repair damaged DNA. The accumulated evidence to date confirms that these machines are dynamically assembled and disassembled rather than existing as preformed complexes, e.g [1]. Moreover, there is extensive cross-talk between them. For example, DNA repair of all types of lesions occurs in tandem with the replication and transcription of DNA, since the exposure of DNA for replication and transcription renders it open to discovery of these lesions. In fact, all aspects of the processing of DNA are integrated events in cellular life.

The conjoining of multiple dynamic protein interactions is a critical feature of DNA processing machinery that enables progression through each pathway. The weak and often transient nature of most if not all of the interactions between the constituent proteins provides a ready means for DNA processing machinery to dynamically assemble and disassemble while handing off the DNA substrate from one sub-complex to another. The most prominent example is polymerase switching (reviewed in [2]). Examples of polymerase switching include the passing of ssDNA from DNA primase to DNA polymerase α to DNA polymerase δ or ε during DNA replication, and from a processive polymerase to a bypass polymerase when a DNA lesion is encountered. The handing off of substrate is also clearly evident in nucleotide excision repair (NER), as this process requires a series of steps to recognize the lesion, position nucleases, remove the damaged nucleotide, and fill in the gap created by excision [3].

The dynamic assembly and disassembly of proteins makes for highly robust DNA processing machines and enables multiple levels of regulation in space and time. This, combined with the parallels in the biochemical steps of different machines, provides for cross-talk between different pathways. Regulation and cross-talk are also facilitated by the presence of certain proteins that are used in multiple pathways. The use of these “hub” proteins in multiple pathways also results in needing fewer copies of such key proteins, since they can be taken from a common pool as needed.

Vast new horizons have opened up in understanding how multi-domain proteins and multi-protein machines function, largely as a result of technical advances in instrumentation and the development of new experimental approaches. As a result, an ever-increasing level of atomic level detail is being discerned. We are now in a position to begin to address the correlations between molecular structure, cellular outcomes, and disease. Key challenges that lie ahead include understanding: (i) How the succession of biochemical activities is orchestrated in multi-protein machines? (ii) How to characterize the dynamic structures of multi-domain proteins and multi-protein machines? Here we highlight some of the concepts that are emerging that explain the action of dynamic multi-domain proteins and multi-protein machinery.

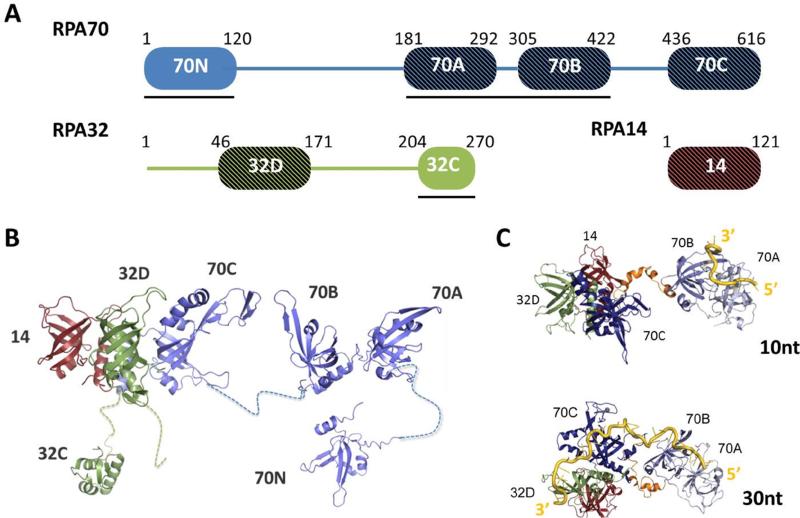

To demonstrate critical characteristics and concepts we will take examples from studies of the abundant eukaryotic ssDNA binding protein, replication protein A (RPA), which is an archetypal example of a dynamic, modular protein. RPA is a 116 kDa hetero-trimer of 70, 32, and 14 kDa subunits that together contain eight functional domains [4][5] (Figure 1). It has no known enzymatic activity but rather functions as a scaffold within many dynamic DNA processing machines. Moreover, through its involvement in these different pathways, it facilitates cross-talk between multiple DNA processing pathways (reviewed in [5]). These, and similar studies of other ubiquitous hub proteins such as PCNA [6][7], are revealing key common characteristics and providing a framework for understanding the dynamic action of modular proteins in multi-protein DNA processing machinery. Although a range of hub proteins have been characterized, the examples provided in the following sections will be limited to RPA in the interest of maintaining coherence and brevity.

Figure 1.

Overview of RPA structure. A) Domain map of the three subunits of RPA. The four DNA binding domains (RPA70A, 70B, 70C and 32D) are identified by cross-hatching and a black line is drawn under the domains that interact with RPA partner proteins. B) Representation of RPA architecture with ribbon diagrams for the globular structures of RPA70N ([12], PDB ID: 1EWI), RPA70AB ([14], PDB ID: 1JMC), RPA70C/32D14 ([17], PDB ID: 1L1O), and RPA32C ([18], PDB ID: 1DPU) and dashed lines for the flexible linkers between the globular domains. The disordered RPA32N domain is not shown. C) Progressive compaction of RPA in its two modes of binding ssDNA. Structural models taken from simulations of the DNA binding core of RPA (RPA70ABC/32D/14) bound to 10 nucleotides or 30 nucleotides of ssDNA. Panel adapted from reference [21].

3. Dynamics in multi-protein machinery

A fundamental advance in understanding of protein machinery is the realization of the pervasive role of dynamics, e.g. [1]. Not only is the machine undergoing dynamic transformations, but the proteins themselves are flexible and constantly adapting to the progression through the multiple biochemical steps of the pathway. Within this dynamic context, the activity of the constituent proteins must be coordinated so there is ordered progression throughout the process. Many important characteristics of the proteins and concepts about the operation of the machinery have been discerned; modularity of the proteins, versatility of common folds, direct competition between sites, the critical role of allostery and other concepts are integrated and provide a framework for understanding the underlying basis for the action of DNA processing machinery (reviewed in [8]).

X-ray diffraction in the crystalline state, NMR and small angle X-ray scattering in solution, and cryo-EM in vitreous ice can provide powerful 3D structural information on multi-protein DNA processing machines. However, because DNA transactions are intrinsically dynamic processes, in order to understand how the machinery functions, the static structural snapshots generated by these approaches must be complemented by methods that characterize the transitions between specific structural states. Although investigations of the dynamics of protein systems are coming of age, the study of the coordinated action of dynamic assemblies of proteins poses significant challenges to current structural biology technologies. Spectroscopic and scattering techniques in solution along with single molecule studies offer a means to directly characterize transitions of multi-molecular complexes in solution [9][10][11].

NMR, scattering, crystallography and computational approaches have been used to build a picture of the dynamic RPA architecture and its remodeling as it binds ssDNA [12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22] . These studies have revealed a hierarchy of inter-domain mobility within RPA that is specifically correlated with function [19]. Notably, remodeling and alignment of multiple domains are observed upon binding the ssDNA substrate, yet no effects are observed on the relative flexibility of the protein interaction domains that recruit and drive assembly of the DNA processing machinery [20][21]. This provides an excellent example of how combining data directly measuring dynamics with the information derived from 3D structures provides unique insights into the molecular mechanisms that enable the coordinated action of the proteins in DNA processing machinery [21]. The dynamics of RPA on ssDNA has also been investigated by single molecule approaches and has provided valuable new insights into the coordinated actions of RPA, Rad51 and Rad52 in homologous recombination [23][24][25].

4. Hub proteins

Hub proteins (also termed keystone proteins or protein nodes) function at the center of multiple DNA processing machines and serve both as a foundation for remodeling of multi-protein complexes and for integration of pathways such as DNA replication, damage response and repair. Hubs are also distinguished by their ability to control and coordinate multi-protein assemblies. These proteins often function as platforms or scaffolds around which dynamic DNA processing machinery assembles and disassembles. Their ability to integrate multiple DNA processing pathways arises because they are common to multiple multi-protein machines. A critical feature of most hub proteins in DNA processing machines is their binding DNA substrates and protein partners with specific orientation, thereby providing much-needed directionality to ensure the machinery functions properly. Many hubs are present during multiple steps of a given pathway, and by remaining on site but oriented, they facilitate direct progression of the machinery on the substrate. For example, RPA functions in multiple steps of nucleotide excision repair (NER). RPA is recruited once the presence of a lesion is recognized, and it remains engaged to the NER substrate as the procession of factors are recruited to excise the damaged nucleotide through to gap filling synthesis after excision has occurred [3].

As a key hub protein, RPA interacts with many other DNA processing proteins (reviewed in [5]). Like all hubs, it has multiple sites for binding protein partners: RPA32C, RPA70N and RPA70AB (Figure 1). Despite their ability to bind multiple partners, the protein interaction sites of hubs are often specific, e.g. the yeast RPA32C domain has been shown to be distinct from the human domain [e.g. [26]]. Nearly all of the binding partners of RPA are enzymes and their chemical action on the substrate typically helps to drive the progression of the corresponding process. For example, RPA helps to recruit the excision nucleases XPG in NER and UNG2 in BER [27][28]. Thus, RPA is well recognized as an organizer and orchestrator of DNA processing, without which the corresponding machinery would not properly function. Because RPA and other hub proteins play similar roles in a range of DNA processing pathways, they are understood to serve as critical for cross-talk, e.g. in the case of RPA between DNA replication, damage signaling, repair, and recombination pathways [5][29][30].

RPA function involves a highly interwoven series of steps integrating binding of ssDNA, interactions with other proteins, and structural rearrangements ranging from local deformation of domains to remodeling of architecture. RPA's interaction with a wide range of partner proteins is consistent with its role as a scaffold orchestrating the processing of DNA. Perhaps the most critical property of RPA is that it binds to ssDNA with a defined 5’→3’ polarity (Figure 1C) [31][32]. This property supports a mechanism in which RPA orients its protein binding partners with respect to the DNA substrate [26]. It has been proposed that RPA coordinates the activities of partner proteins through molecular hand-off via competition-based switching between binding sites [18][34][35].

5. Modularity

A critical feature of proteins involved in all DNA processing machines is the flexible linkage of structural/functional domains, which enables the coordination of biochemical activities without fixed spatial constraints. In particular, this flexible tethering allows co-localization of different biochemical activities associated with different domains. The power of this design is that it enables essential biochemical steps in a pathway to be performed independently while maintaining high local concentration.

In this sense RPA is an archetypal hub protein. The heterotrimer contains 7 globular domains, including six oligonucleotide-oligosaccharide binding (OB) folds (Figure 1). Four of the OB domains (70A, 70B, 70C, and 32D) provide the ssDNA binding activity [26][4]. The two other OB fold domains mediate protein-protein interactions; RPA14 stabilizes the trimer core (RPA70C/32D/14) and RPA70N acts as a partner protein recruitment module [36][5]. The C-terminal domain of RPA32 (RPA32C) is a winged-helix domain also serving for recruitment of partner proteins [18]. Although atomic-resolution structures have been determined for all of the domains [36], there is a significant gap in understanding how RPA actually functions because only very little is known about the spatial disposition of the domains (architecture) and how changes in architecture are used to drive function [21][22].

6. Multiple binding partners

As central players in DNA processing machinery, hub proteins serve to recruit multiple proteins to the DNA substrate and also orient them to ensure they function efficiently. RPA serves as a paradigm example as it is required for virtually all aspects of DNA processing, and has been shown to interact not only with ssDNA independent of sequence, but also with a very large number of other DNA processing proteins (reviewed in [5]). In fact, RPA-coated ssDNA is created in many DNA transactions and is even viewed as the primary initiator of the DNA damage response; when DNA lesions cause uncoupling of the helicase and polymerase activities at the replication fork, RPA-coated ssDNA is accumulated and serves to recruit the damage checkpoint kinase ATR and a number of damage response proteins to the lesion [37][38]. Among the many proteins that are purported to bind RPA, direct physical interaction has been shown using NMR mapping of binding interfaces for Rad51, XPA, UNG2, Rad52, SV40 T antigen helicase, DNA primase, ATRIP, MRE11, Rad9, BID, TIPIN, and HDHB [39][18][40][41][42][38][43][44][45]. With so many different binding partners but only limited partner protein binding surfaces, it is obvious that many of the binding sites overlap and are mutually exclusive. The commonality of the binding sites is an integral part of pathway choice and also contributes significantly to coordination of steps in a given pathway and cross-talk between pathways [26][27].

7. Structural mechanisms for mediating assembly, disassembly, exchange and hand-off

The progression through a DNA processing pathway requires (i) the assembly and disassembly of the enzymes that perform the chemical processing and (ii) the transitions in the architecture of the machinery that enable the exchange of relevant enzymes and hand-off of the substrate. There are multiple mechanisms that are utilized by the proteins and complexes to provide the necessary flexibility for the machinery, while maintaining the ordered progression of substrate processing. The following sections summarize some of the key mechanisms that enable the complex machinery to function properly.

7.1. Direct competition for binding sites

As noted above, proteins in DNA processing assemblies have more than one binding surface (site) for interactions with DNA and partner proteins. It is not uncommon for these binding sites to be clustered together and/or overlapping, which sets up competition for the site(s) as a means to control pathway progression. The direct competition for a site is a direct means to ensure exchange of enzymes within the machinery and can also be critical to handing off the DNA substrate. In addition, competition for binding sites can serve as a direct mechanism for enabling pathway choice for processing a DNA intermediate or lesion. Direct competition also allows for temporal regulation, for example as the levels of different protein binding partners change over time, mass action will lead to changes in which protein is bound.

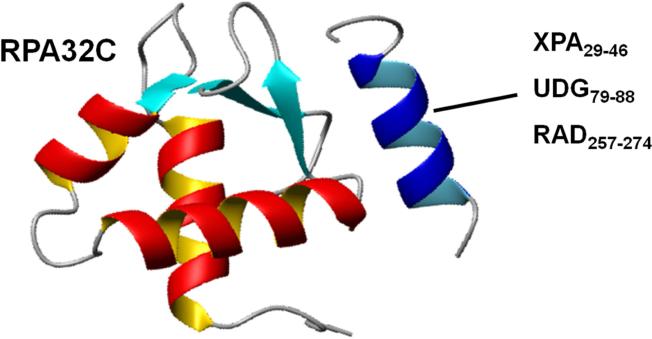

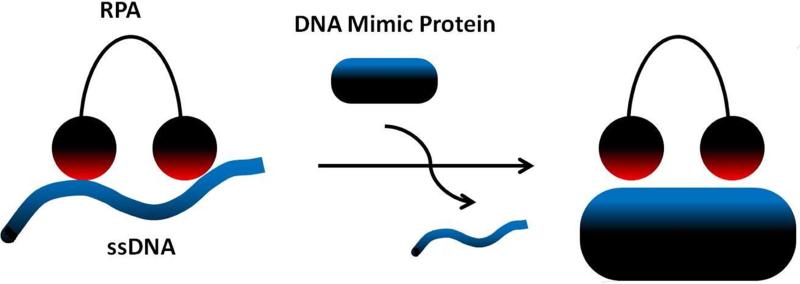

Competition for the protein interaction sites of RPA is critical because it precludes simultaneous binding of different components of the machinery, which promotes ordered progression down a pathway. Thus, proteins acting at later stages of the pathway displace those acting at earlier time points. Competition is also important in pathway choice, for example in DNA repair. Support for the role of competition in pathway choice was provided in a study of RPA32C, which was shown to bind a common motif from XPA, Rad52, and UNG2 [18] (Figure 2), which are involved in nucleotide excision, base excision, and recombination repair, respectively. Overlap between protein and ssDNA binding sites has also been observed for RPA. NMR mapping of binding sites on RPA70A for the DNA binding domain of XPA and for the small N-terminal domain of Rad51 revealed that both proteins interact directly in the ssDNA binding site [46][39]. DNA mimicry, in which a disordered, highly acidic region of a DNA processing protein displaces DNA (Figure 3), represents a specialized case of competition between sites that has become increasingly recognized as the mechanistic basis for function [47].

Figure 2.

Competition for sites. Ribbon diagram of the structure of the RPA32C protein recruitment domain in complex with the binding motif from the base excision repair protein UNG2. The labeling at right indicates the homologous motifs from XPA (nucleotide excision repair) and Rad52 (recombination repair) that bind in the same site.

Figure 3.

DNA mimicry. Schematic diagram showing a protein domain with highly acidic character displacing ssDNA from an RPA binding site. Red – positive charge. Blue – negative charge.

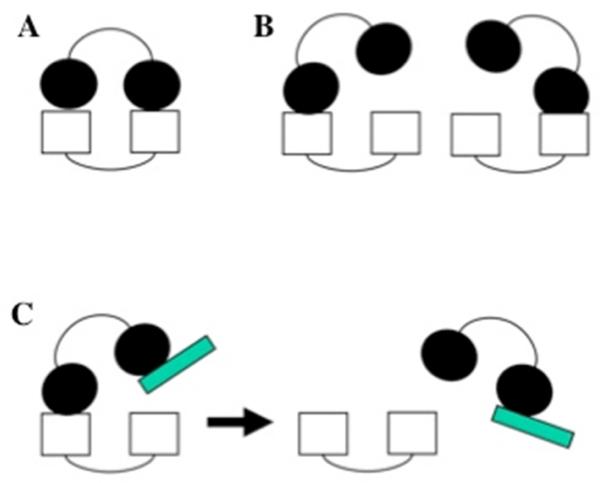

7.2. Allostery

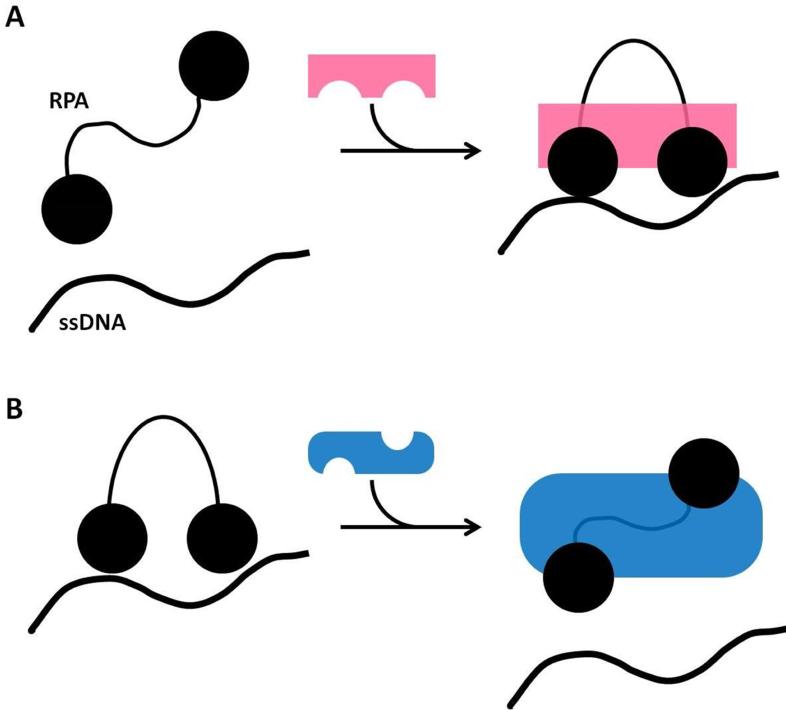

Action at a remote site, termed allostery, is another key mechanism that mediates transitions in DNA processing machinery. Allostery is broadly defined as binding of a ligand molecule at one site that causes shifts in the structure and/or dynamics at a different site. The effect of an allosteric interaction can be either stimulatory or inhibitory (Fig. 4). There are numerous ways in which allosteric effects are used, one of the most common being induction of conformational changes that expose an otherwise sequestered target binding surface. Other common examples include inducing oligomerization or altering the distribution between conformational substates. Allostery can also be coupled to other structural mechanisms for assembly, disassembly, exchange and hand-off at critical stages of DNA processing.

Figure 4.

Allostery. Schematic diagram representing how binding of a protein binding partner at a remote site from the DNA binding domain can stimulate (A) or inhibit (B) the interaction with ssDNA.

An interesting allosteric interaction has been reported involving RPA and a mediator of homologous recombination, Rad52 [48]. In this study, binding of Rad52 to the RPA32C protein recruitment domain was found to stimulate the ssDNA binding affinity of RPA by a factor of 5, and has been attributed to increase binding to the RPA32D domain. Another case of allostery involves the interaction of the origin binding domain (OBD) of SV40 T antigen helicase with RPA70AB. The OBD binds at site on the opposite side of the DNA binding sites of RPA70AB and it allosterically stimulates the ssDNA binding affinity [41]. A specific mechanism was proposed wherein the binding of the OBD pre-pays the entropic penalty of reducing the flexibility between the two domains, thereby lowering free energy of binding. These are specific examples that support a more general proposal that binding of partner proteins to RPA allosterically modulates the architecture and DNA binding activity of RPA to promote pathway progression [21].

7.3. The power of multi-valency

The modular nature of the proteins naturally leads to another critically important characteristic: the generation of selectivity in interactions through the use of multiple contact points between binding partners, each with weak to modest affinity. Multiple contact points are essential for generating high overall affinity from a set of much weaker individual interactions. It also facilitates making transitions in the machinery involving rearrangement as opposed to dissociation, as well as in multiple levels of regulation [8].

The value of multiple contact points is that by tethering two or more weak (dissociation constants (Kd) in the high μM range) interactions together, the interacting proteins are bound with high overall affinity, yet each contact maintains a significant off-rate (Figure 5). As a consequence, the two binding partners can be disassembled quite rapidly: by inhibiting just one of the weak interactions, the Kd is reduced by orders of magnitude instantaneously. Such a fast transition between high and low-affinity binding states provides a means for rapid response, hand-off, and transition in the DNA repair machinery. Although very simplistic, this model [8] provides a starting point for the development of more sophisticated formalisms that will provide deeper insights into the structural mechanisms used by the multi-domain proteins and multi-protein assemblies involved in DNA processing.

Figure 5.

Multivalent binding. (A) Schematic representation of the interaction between two molecules mediated by two discrete contacts. The binding affinity in this system approaches the product of the affinities for each contact. As an example, if the Kd for each contact is 100 μM, the overall affinity could be as high as 10 nM. (B) Representation of transient states when one contact is released but the other remains bound. The binding affinity in this system is invariably substantially more dynamic than if the full energy of binding was provided by a single contact. (C) Representation of how blocking of one contact rapidly reduces the overall binding affinity (e.g. 10 nM) to that of a single contact (e.g. 100 μM). This demonstrates the power of multivalency for generating the rapid transitions needed in multi-protein DNA processing machinery while supporting the high overall affinity required for the assembly of functional protein complexes. Adapted from reference [8].

The interactions between different contact points need not be of equal affinities. This is clearly the case for RPA, which typically has a primary interaction through one or the other of the two recruitment modules (RPA70N and RPA32C) along with a secondary interaction with the tandem RPA70AB domains. Interactions with RPA70N and RPA32C that have been quantified all seem to fall within a Kd range of of 1-30 μM (e.g. RPA32C with XPA, UNG2, RAD52 [18] and RPA70N with ATRIP, MRE11, RAD9 [38]). The interactions with RPA70AB are much harder to quantify because they are substantially weaker (Kd ~ 200-2000 μM) (e.g. [39][41]). In our favored model, partner proteins are initially recruited by stronger contact with RPA70N or RPA32C, which increases the local concentration and thereby promotes the interaction with RPA70AB. The interaction with the tandem DNA binding domains RPA70AB could then directly or allosterically weaken affinity for DNA to facilitate access for the partner protein to perform its enzymatic function (Figure 4) [21].

8. Outlook and conclusions

A view emerging from a wide range of studies is that highly dynamic DNA processing machines are composed of modular proteins with multiple, structurally independent functional domains. These proteins interact with DNA and/or multiple protein partners from the machinery through interactions that are also modular. The contacts are characterized by relatively low (μM) binding affinities, a property that promotes exchange of proteins and hand-off of the DNA substrate. The linkage of multiple, weak interactions is the key to generating the requisite affinity and selectivity. There are a variety of structural mechanisms governing the transitions of the machinery, ranging from straightforward competition to highly complex allosteric effects. With rapidly advancing technical development in the production and isolation of functional protein assemblies and in approaches to characterize their complex structural dynamics, we anticipate quantum leaps forward in understanding the action of multi-domain DNA processing proteins and their coordinated function in multi-protein machinery.

Acknowledgements

We thank Chris A. Brosey for help with preparing Figure 1. Research on DNA processing machinery in our laboratory is supported by operating and center grants from the US National Institutes of Health (RO1 GM65484, PO1 CA092584, RO1 ES016561, P30 ES00267, P30 CA068485).

Abbreviations

- RPA

replication protein A

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- NER

nucleotide excision repair

- Kd

dissociation constant

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Langston LD, Indiani C, O'Donnell M. Whither the replisome: Emerging perspectives on the dynamic nature of the DNA replication machinery. Cell Cycle. 2014;8:2686–2691. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.17.9390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovett ST. Polymerase switching in DNA replication. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:523–6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riedl T, Hanaoka F, Egly J. The comings and goings of nucleotide excision repair factors on damaged DNA. EMBO J. 2003;22:5293–5303. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wold M. Replication protein A: a heterotrimeric, single-stranded DNA-binding protein required for eukaryotic DNA metabolism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1997;66:61–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fanning E, Klimovich V, Nager AR. A dynamic model for replication protein A (RPA) function in DNA processing pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4126–37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Biasio A, Blanco FJ. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen structure and interactions: too many partners for one dancer? 1st ed. Vol. 91. Elsevier Inc.; 2013. pp. 1–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mailand N, Gibbs-Seymour I, Bekker-Jensen S. Regulation of PCNA-protein interactions for genome stability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:269–82. doi: 10.1038/nrm3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stauffer ME, Chazin WJ. Structural mechanisms of DNA replication, repair, and recombination. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:30915–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain A, Liu R, Ramani B, Arauz E, Ishitsuka Y, Ragunathan K, Park J, Chen J, Xiang YK, Ha T. Probing cellular protein complexes using single-molecule pull-down. Nature. 2011;473:484–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Göbl C, Madl T, Simon B, Sattler M. NMR approaches for structural analysis of multidomain proteins and complexes in solution. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2014;80:26–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Putnam CD, Hammel M, Hura GL, Tainer JA. X-ray solution scattering (SAXS) combined with crystallography and computation: defining accurate macromolecular structures, conformations and assemblies in solution. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2007;40:191–285. doi: 10.1017/S0033583507004635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs D, Lipton A, Isern N, Daughdrill GW, Lowry DF, Gomes X, Wold MS. Human replication protein A: Global fold of the N-terminal RPA-70 domain reveals a basic cleft and flexible C-terminal linker. J. Biomol. 1999;14:321–331. doi: 10.1023/a:1008373009786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bochkareva E, Kaustov L, Ayed A, Yi G-S, Lu Y, Pineda-Lucena A, Liao JCC, Okorokov AL, Milner J, Arrowsmith CH, Bochkarev A. Single-stranded DNA mimicry in the p53 transactivation domain interaction with replication protein A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:1–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504614102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bochkarev A, Pfuetzner R, Edwards A, Frappier L. Structure of the single- stranded-DNA-binding domain of replication protein A bound to DNA. Nature. 1997;385:176–181. doi: 10.1038/385176a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bochkareva E, Belegu V, Korolev S, Bochkarev A. Structure of the major single- stranded domain of replication protein A suggests a dynamic mechanism for DNA binding. EMBO J. 2001;20:612–618. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bochkarev A, Bochkareva E, Frappier L, Edwards AM. The crystal structure of the complex of replication protein A subunits RPA32 and RPA14 reveals a mechanism for single-stranded DNA binding. EMBO J. 1999;18:4498–4504. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bochkareva E, Korolev S, Lees-Miller SP, Bochkarev A. Structure of the RPA trimerization core and its role in the multistep DNA-binding mechanism of RPA. EMBO J. 2002;21:1855–1863. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mer G, Bochkarev A, Gupta R, Bochkareva E, Frappier L, Ingles CJ, Edwards AM, Chazin WJ. Structural basis for the recognition of DNA repair proteins UNG2, XPA, and RAD52 by replication factor RPA. Cell. 2000;103:449–456. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brosey CA, Chagot M-E, Ehrhardt M, Pretto DI, Weiner BE, Chazin WJ. NMR Analysis of the Archtecture and Functional Remodeling of a Modular Multi-Domain Protein, RPA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:6346–6347. doi: 10.1021/ja9013634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pretto DI, Tsutakawa S, Brosey CA, Castillo A, Chagot M-E, Smith JA, Tainer JA, Chazin WJ. Structural dynamics and single-stranded DNA binding activity of the three N-terminal domains of the large subunit of replication protein A from small angle X-ray scattering. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2880–9. doi: 10.1021/bi9019934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brosey CA, Yan C, Tsutakawa S, Heller WT, Rambo RP, Tainer JA, Ivanov I, Chazin WJ. A new structural framework for integrating replication protein A into DNA processing machinery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:2313–27. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan J, Pavletich NP. Structure and conformational change of a replication protein A heterotrimer bound to ssDNA. Genes Dev. 2012;26:2337–47. doi: 10.1101/gad.194787.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibb B, Ye LF, Gergoudis SC, Kwon Y, Niu H, Sung P, Greene EC. Concentration-dependent exchange of replication protein A on single-stranded DNA revealed by single-molecule imaging. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibb B, Ye LF, Kwon Y, Niu H, Sung P, Greene EC. Protein dynamics during presynaptic-complex assembly on individual single-stranded DNA molecules. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:893–900. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deng SK, Gibb B, de Almeida MJ, Greene EC, Symington LS. RPA antagonizes microhomology-mediated repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:405–412. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iftode C, Daniely Y, Borowiec J. Replication protein A (RPA): the eukaryotic SSB. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1999;34:141–180. doi: 10.1080/10409239991209255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He Z, Henricksen L, Wold M, Ingles C. RPA involvement in the damage-recognition and incision steps of nucleotide excision repair. Nature. 1995;6:566–569. doi: 10.1038/374566a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagelhus TA, Haug T, Singh KK, Keshav KF, Skorpen F, Otterlei M, Bharati S, Lindmo T, Benichou S, Benarous R, Krokan HE. A Sequence in the N-terminal Region of Human Uracil-DNA Glycosylase with Homology to XPA Interacts with the C-terminal Part of the 34-kDa Subunit of Replication Protein A. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:6561–6566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oakley G, Patrick S. Replication protein A: directing traffic at the intersection of replication and repair. Front. Biosci. J. 2010;15:883–900. doi: 10.2741/3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zou Y, Liu Y, Wu X, Shell S. Functions of human replication protein A (RPA): from DNA replication to DNA damage and stress responses. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006;273:267–273. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wyka I, Dhar K, Binz S, Wold M. Replication protein A interactions with DNA: differential binding of the core domains and analysis of the DNA interaction surface. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12909–12918. doi: 10.1021/bi034930h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arunkumar AI, Stauffer ME, Bochkareva E, Bochkarev A, Chazin WJ. Independent and coordinated functions of replication protein A tandem high affinity single-stranded DNA binding domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:41077–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Laat WL, Appeldoorn E, Sugasawa K, Weterings E, Jaspers NGJ, Hoeijmakers JHJ. DNA-binding polarity of human replication protein A positions nucleases in nucleotide excision repair. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2598–2609. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kowalczykowski SC. Some assembly required. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:1087–1089. doi: 10.1038/81923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuzhakov A, Kelman Z, O’Donnell M. Trading places on DNA—a three-point switch underlies primer handoff from primase to the replicative DNA polymerase. Cell. 1999;96:153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80968-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mer G, Bochkarev A, Chazin WJ, Edwards AM. Three-dimensional structure and function of replication protein A. Cold Spring Harb. 2000;65:193–200. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2000.65.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zou L, Elledge S. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science. 2003;300:1542–1547. doi: 10.1126/science.1083430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu X, Vaithiyalingam S, Glick GG, Mordes DA, Chazin WJ, Cortez D. The basic cleft of RPA70N binds multiple checkpoint proteins, including RAD9, to regulate ATR signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28:7345–53. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01079-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stauffer M, Chazin W. Physical interaction between replication protein A and Rad51 promotes exchange on single-stranded DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:25638–25645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arunkumar AI, Klimovich V, Jiang X, Ott RD, Mizoue L, Fanning E, Chazin WJ. Insights into hRPA32 C-terminal domain--mediated assembly of the simian virus 40 replisome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:332–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmbXX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang X, Klimovich V, Arunkumar AI, Hysinger EB, Wang Y, Ott RD, Guler GD, Weiner B, Chazin WJ, Fanning E. Structural mechanism of RPA loading on DNA during activation of a simple pre-replication complex. EMBO J. 2006;25:5516–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaithiyalingam S, Warren EM, Eichman BF, Chazin WJ. Insights into eukaryotic DNA priming from the structure and functional interactions of the 4Fe-4S cluster domain of human DNA primase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:13684–13689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002009107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y, Vaithiyalingam S, Shi Q, Chazin WJ, Zinkel SS. BID binds to replication protein A and stimulates ATR function following replicative stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011;31:4298–309. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05737-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ali SI, Shin J-S, Bae S-H, Kim B, Choi B-S. Replication protein A 32 interacts through a similar binding interface with TIPIN, XPA, and UNG2. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010;42:1210–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guler GD, Liu H, Vaithiyalingam S, Arnett DR, Kremmer E, Chazin WJ, Fanning E. Human DNA helicase B (HDHB) binds to replication protein A and facilitates cellular recovery from replication stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:6469–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.324582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buchko GW, Daughdrill GW, de Lorimier R, Rao B K, Isern NG, Lingbeck JM, Taylor JS, Wold MS, Gochin M, Spicer LD, Lowry DF, Kennedy MA. Interactions of human nucleotide excision repair protein XPA with DNA and RPA70 Delta C327: chemical shift mapping and 15N NMR relaxation studies. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15116–15128. doi: 10.1021/bi991755p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dryden D, Tock M. DNA mimicry by proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006;34:317–319. doi: 10.1042/BST20060317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson D, Dhar K, Wahl JK, Wold MS, Borgstahl GE. Analysis of the Human Replication Protein A:Rad52 Complex: Evidence for Crosstalk Between RPA32, RPA70, Rad52 and DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;321:133–148. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00541-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]