Abstract

Introduction

Cue reactivity paradigms have found that alcohol-related cues increase alcohol consumption in heavy drinkers and alcoholics. However, evidence of this relationship among non-alcohol dependent “social” drinkers is mixed, suggesting that individual differences must be considered when examining cue-induced drinking behavior. One important individual difference factor that might contribute to cue-induced drinking in the laboratory is the amount of alcohol that participants typically drink during occasions outside the laboratory. That is, those who typically consume more alcohol per occasion could display greater cue-induced drinking than those who typically drink less. The present study examined this hypothesis in healthy, non-dependent beer drinkers.

Methods

The drinkers were exposed to either a series of beer images intended to prime their motivation to drink beer or to a series of non-alcoholic images of food items that served as a control condition. Following cue exposure, motivation to drink was measured by giving participants an opportunity to work for glasses of beer by performing an operant response task.

Results

Results indicated that drinkers exposed to alcohol cues displayed greater operant responding for alcohol and earned more drinks compared with those exposed to non-alcohol (i.e., food) cues. Moreover, individual differences in drinking habits predicted subjects’ responding for alcohol following exposure to the alcohol cues, but not following exposure to food cues.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that cue-induced drinking in non-dependent drinkers likely results in consumption levels commensurate with their typical consumption outside the laboratory, but not excessive consumption that is sometimes observed in alcohol-dependent samples.

Keywords: alcohol, cue reactivity, drinking habits, craving, operant, social drinkers

1. Introduction

It has long been known that alcohol cues induce reactions in drinkers which may increase alcohol-seeking behavior. Indeed, decades of cue reactivity research has shown that exposure to alcohol cues can lead to physiological and subjective changes in an individual that are assumed to underlie increased craving for alcohol. In general, these studies have shown that exposure to alcohol cues may induce changes in heart rate, blood pressure, skin conductance, salivation, as well as changes in self-reported mood, and subjective craving for alcohol (e.g., Beirness & Vogel-Sprott, 1984; Drummond, 2000; Field & Duka, 2002; Fox, Bergquist, Hong, & Sinha, 2007; Monti, Binkoff, Abrams, Zwick, Nirenberg, & Liepman, 1987; Newlin, 1986; Staiger & White, 1988).

In terms of actual alcohol consumption, cue reactivity studies have attempted to show that alcohol cues can prime the motivation to drink. Individuals in these studies are typically shown alcohol cues (e.g., alcohol bottle or alcohol images) or neutral cues (e.g., food items or office supplies). The degree to which such cue exposure primes alcohol consumption is measured by how much alcohol is subsequently consumed by subjects when given ad libitum access to alcohol, or during bogus taste-rating tasks where they are asked to sample and evaluate the taste of alcoholic beverages (Carter & Tiffany, 1999). Studies using these methods have shown that alcohol cues increase alcohol consumption in alcoholics (e.g., Cooney, Baker, Pomerleau, & Josephy, 1984; Kaplan, Cooney, Baker, Gillespie, Meyer, & Pomerleau, 1985; Ludwig, Wikler, & Stark, 1974; Monti, et al., 1987).

The most compelling evidence that alcohol cues prime the motivation to drink in these individuals has been demonstrated by cue reactivity studies that use operant response tasks in which participants must “work” to obtain alcoholic drinks according to fixed or progressive ratio schedules. Operant tasks are said to provide a more direct assessment of the motivation to drink because the tasks require work or effort on the part of the subject to acquire alcohol compared with ad libitum access or taste-rating measures where alcohol is simply freely available (Fillmore & Rush, 2001; Hursh & Silberberg, 2008; Stafford, LeSage, & Glowa, 1998). Operant tasks assess motivation to drink by the number of operant responses displayed for alcohol, and in the case of progressive ratios, by the highest ratio of responses completed for an alcoholic drink (i.e., the breakpoint). Their use as measures of motivation to drink has been documented for some time, particularly their ability to detect cue-induced priming of drinking behavior in alcoholics (e.g., Mello & Mendelson, 1965; Mendelson & Mello, 1966; Nathan, O’Brien, & Lowenstein, 1971).

Although such studies provide compelling support for the idea that alcohol cues can motivate excessive alcohol consumption, the finding is almost entirely based on samples of alcohol-dependent or problem drinkers, such as binge drinkers (Carter & Tiffany, 1999). Evidence for cue-induced drinking in nondependent (i.e., social) drinkers has been equivocal (Tiffany, 2000). There could be several reasons for the failure to reliably observe cue-induced drinking in social drinkers. It is generally accepted that alcohol cues (e.g., images of alcoholic beverages) motivate drinking behavior because they have acquired conditioned incentive properties having been previously paired with the rewarding effects of consuming alcohol. With repeated pairing, the cues themselves come to elicit an incentive effect that motivates the drinker to seek alcohol (e.g., Mitt, Cooney, Kadden, & Gaupp, 1990; Tiffany & Conklin, 2000). Accordingly, one explanation for the failure to observe cue-induced drinking behavior in social drinkers might simply be that social drinkers have not had a sufficient drinking history necessary to develop conditioned responses to alcohol cues (Vogel-Sprott & Fillmore, 1999). However, this seems somewhat unlikely given that social drinkers readily display other conditioned reactions (e.g., physiological and behavioral changes) in response to alcohol cues (e.g., Laberg, Hugdahl, Stormark, & Nordby, 1992; Monti et al., 1993; Niaura, Rohsenow, Binkoff, Monti, Pedraza, & Abrams, 1988).

Another explanation is that the general notion that alcohol cues should motivate excessive drinking in social drinkers might not be tenable. There is little reason to expect that a non-dependent, social drinker with no history of heavy drinking would drink excessively in response to alcohol cues, especially in a comparatively sterile laboratory environment. Indeed, for such individuals, exposure to alcohol cues might at the most, prime motivation to consume an amount of alcohol commensurate with amounts they typically consume during a drinking occasion outside the laboratory. Thus for non-dependent drinkers an important factor in the degree to which alcohol cues might prime the motivation to drink is the amount of alcohol typically consumed by the individual outside the laboratory. That is, for non-dependent drinkers, alcohol cue exposure in the laboratory might, at the most, instigate the subject to drink an amount of alcohol that they would typically consume outside the laboratory. Such an account could explain why alcohol cue exposure often fails to “prime” alcohol consumption in social drinkers beyond levels observed in control conditions in which social drinkers are exposed to non-alcoholic “neutral” cues.

The present study sought to test the hypothesis that exposure to alcohol cues primes motivation to drink in social drinkers at quantities that are generally commensurate with their own individual typical quantities consumed per occasion outside the laboratory. Participants provided measures of their typical drinking habits and then completed an alcohol cue exposure treatment followed by a test of their motivation to drink using an operant response task. A group of control subjects underwent the identical procedure but were exposed to non-alcohol (i.e., food) cues. It was predicted that alcohol cue exposure would prime the motivation to drink, but that operant responding for alcohol would be generally proportionate to the subject’s quantity of alcohol typically consumed per occasion outside the laboratory. Thus the amount of alcohol earned on the operant response task was expected to be positively related to the subjects’ typical quantity of alcohol consumed outside the laboratory. By contrast, food cues were not predicted to prime subjects’ motivation to drink, and thus no such relationship was predicted between their typical drinking habits and their operant responding for alcohol in the laboratory.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Forty-eight adults between 21 and 35 years of age participated in this study. Twenty-four subjects (10 women and 14 men) were randomly assigned to the alcohol cue exposure treatment and twenty-four subjects (11 women and 13 men) were randomly assigned to the food cue exposure treatment. The racial makeup of the sample was Caucasian (n = 40), African-American (n = 4), American Indian/Alaskan Native (n = 1), Hispanic/Latino (n = 1), and those reporting “other” (n = 2). Volunteers completed questionnaires that provided information on demographics, drinking habits, other drug use, and physical and mental health status. For inclusion, all volunteers had to report at least bi-monthly consumption of alcohol and had to indicate that beer was their preferred beverage. Volunteers who self-reported head trauma, psychiatric disorder, or substance abuse disorder were excluded from participation. Volunteers were also excluded if their current alcohol use met dependence/withdrawal criteria as determined by the substance use disorder module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV). As an additional screening measure for alcohol dependence, volunteers scoring 5 or higher on the Short-Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (Selzer, Vinokur, & Van Rooijen, 1975) were excluded from participation in the study.

No participant reported the use of any psychoactive prescription medication and recent use of amphetamines (including methylphenidate), barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cocaine, opiates, and tetrahydrocannabinol was assessed by means of urine analysis. Any volunteer who tested positive for the presence of any of these drugs was excluded from participation. No female volunteers who were pregnant or breast-feeding participated in the research. The University of Kentucky Medical Institutional Review Board approved the study, and participants received $60 for their participation.

2.2. Apparatus and materials

2.2.1. Cue exposure treatment

Participants were exposed to a series of images of appetitive stimuli that were either alcohol-related or food-related. The images were presented at 5 3/4 inches by 7 1/4 inches on a computer display. For the alcohol cue exposure treatment, participants were required to view 40 alcohol-related images, 20 complex scenes with alcohol embedded (i.e., no greater than 30% of the image) and 20 simple images in which alcohol was the sole object (e.g., a bottle of beer). In order to ensure that the alcohol images were appealing to beer drinkers, all of the alcohol images consisted of beer. The images were selected to emphasize the positive aspects of drinking beer. Images depicted cold beer being poured into frosted glasses, people enjoying beer in pleasant social settings, and the like. Each image was presented for 15 seconds with a 2 second inter-image interval between images during which a blank screen was visible. Participants completed the task in two sets of 20 images, (10 complex and 10 simple). To ensure that participants attended to the images, they were informed that the images were part of a memory test. Prior to the first set, participants were told that the purpose of the task was to closely inspect the images for later recall during the session. The second set served as the memory task, ostensibly to measure participants’ recall of images from the first set. During the memory task, participants were told to respond (old/new) if the image shown was presented during the first set or if it was a new image. Participants were informed that many of the images would be new and that they should make their best guess if they were unsure whether an image was old or new. Indeed, only one image from set 2 was repeated from set 1. Thus, participants viewed 39 unique alcohol images during their cue exposure treatment. Participants in the neutral image condition completed the same procedure with food-related images. The entire cue exposure treatment phase required approximately 13 minutes to complete.

2.2.2. Operant response task

Cue-induced motivation to drink was measured by responding for alcoholic beverages on an operant response task that required an increasing number of mouse clicks to earn each successive serving of beer. Participants were told that they would work to earn glasses of beer that they could subsequently drink during the study. To ensure that the beer would be somewhat rewarding, we offered a modest selection of beer brands with the aim that at least one brand might appeal to a given participant. Participants were shown a menu of four beers (i.e., Bud Light™, Miller Lite™, Sam Adams Lite™, and Newcastle Brown Ale™) and told they would have the option to mix and match the beers to their preference. The beers were chosen to provide variety to participants while maintaining similar alcohol contents (i.e., 4.2%-4.7% ABV). The task required volunteers to sit in front of a standard 19-inch computer display and participants were told they would have the opportunity to earn 5 ounce (~148 ml) servings of beer by repeatedly clicking the left mouse button. At certain points they were presented with a congratulatory message and a short clip of shooting fireworks letting them know that they had earned a beer. Participants could earn drinks by completing a progressively increasing number of responses on the task: 100, 300, 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, 2500, and 3000 mouse clicks. Participants were not informed of the maximum 8 beer servings that could be earned on the task. Immediately following a beer reward, the computer asked participants (yes/no) if they would like to continue to earn another beer. They were also given the option to let the researcher know if they would like to stop the task at any point between these prompts. Before starting the task, participants were informed that upon completion of the task they would be moved to a leisure area where they could relax in a reclining chair and watch movies, eat snacks, and drink the beers earned on the task. This area was designed to be as comfortable as possible as to mimic a natural drinking environment. Participants only had access to beers earned once they completed all response requirements or chose to stop responding for beer. To ensure that the session completion time did not influence drinks earned, volunteers were instructed at the outset that they would remain in the lab for the full study duration despite the amount of beer they chose to work for. The primary measures of motivation for alcohol were the total number of operant responses for alcohol and total number of drinks earned.

2.2.3. Personal drinking habits questionnaire (PDHQ, Vogel-Sprott, 1992)

Participants completed the PDHQ which provided information on the number of standard drinks per drinking occasion, frequency of drinking episodes, duration of a typical drinking episode, and participants’ lifetime experiences with alcohol.

2.2.4. Self-reported craving

Subjects’ subjective level of craving for alcohol was examined in the study using a 10-point scale that ranged from 0 “not at all” to 10 “very much”. These Likert-type scales are commonly used to measure changes in craving in cue reactivity studies (e.g., Fox, Bergquist, Hong, & Sinha, 2007; Harrison & Fillmore, 2005; Harrison, Marczinski, & Fillmore, 2007).

2.3. Procedure

Interested volunteers responded to study advertisements by calling the laboratory to participate in an intake-screening interview conducted by a research assistant. At that time, they were informed that the purpose of the study was to examine the effects of alcohol on behavioral tasks. Volunteers were asked to report their preferred alcoholic beverage (beer, wine, or liquor). Because the operant task used beer as a reward and the cue exposure presented only images of beer, only volunteers reporting beer as their preferred beverage were eligible for study participation. All sessions were conducted in the Behavioral Pharmacology Laboratory of the Department of Psychology and testing began between 12 p.m. and 6 p.m. All participants were tested individually and provided informed consent. Subjects attended two sessions: an intake assessment session and a cue exposure session. Sessions were scheduled at least 24 hours apart with a maximum inter-session interval of one week. Participants were instructed to refrain from alcohol or any psychoactive drugs or medications for 24 hours before each session. Prior to each session, participants provided urine samples that were tested for drug metabolites, including amphetamine, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cocaine, opiates, and tetrahydrocannabinol (ON trak TesTstiks, Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and, in women, HCG, in order to verify that they were not pregnant (Mainline Confirms HGL, Mainline Technology, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Breath samples were also provided and analyzed by an Intoxilyzer, Model 400 (CMI, Inc., Owensboro, KY, USA) at the beginning of each session to verify a zero breath alcohol content (BrAC).

During the initial intake session subjects were acquainted with laboratory procedures and provided background information (i.e., demographics and drinking habits). Arrangements to attend the cue exposure session were made at the completion of the intake session and volunteers were randomly assigned to one of two cue exposure conditions (i.e., alcohol cue versus food cue).

The cue exposure session began with a pre-cue exposure measure of craving for alcohol. This was followed immediately by the first cue exposure treatment. After a short break, subjects completed the second cue exposure treatment (i.e., memory recall task). Immediately following cue exposure, participants provided a post-cue exposure rating of craving for alcohol and then were given an opportunity to work for beer on the operant response task. When participants chose to stop responding or all eight beers were earned, they were allowed to consume the beer they had earned. Beer was consumed in a separate room that was designed as a naturalistic lounge area where participants could watch movies, listen to music, or read magazines. The session length was set at 5 hours. After 5 hours, most participants had BrAC readings below 20 mg/100 ml and they were released. Participants with BrACs above 20 mg/100 ml remained in the lounge until they reached this point. Transportation home was provided after the session.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics, drinking history, and drug use

Table 1 presents participants’ mean age and drinking habits as measured by the PDHQ. There were no group differences in age in either cue condition (p = .68). There were also no group differences in typical quantity of alcohol consumed, typical duration of drinking episodes, weekly frequency of drinking occasions, or lifetime drinking experience (ps > .30). In terms of other drug use, three drinkers in the alcohol cue condition reported using cannabis an average of 1.6 times in the past month and three drinkers in the food cue condition reported cannabis use an average of 1.0 times in the past month. No other drug use was reported.

Table 1.

Drinking Habits

| Food Cue | Alcohol Cue | t | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | |||

| Age | 24.0 | (3.0) | 24.5 | (4.6) | 0.41 | .68 |

| PDHQ | ||||||

| Typical quantity | 3.6 | (2.1) | 4.2 | (2.4) | 0.82 | .42 |

| Weekly frequency | 1.9 | (1.1) | 2.0 | (1.1) | 0.29 | .78 |

| Typical duration | 3.4 | (1.3) | 3.4 | (1.1) | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Total months | 73.5 | (39.1) | 89.3 | (62.9) | 1.05 | .30 |

Age = subjects’ age in years at time of participation; Typical quantity = PDHQ typical quantity of drinks consumed per drinking occasion; Weekly frequency = PDHQ number of drinking episodes per week; Typical duration = PDHQ length of a typical drinking episode in hours; Total months = PDHQ lifetime drinking experience in months.

3.2. Cue exposure effects on operant responding

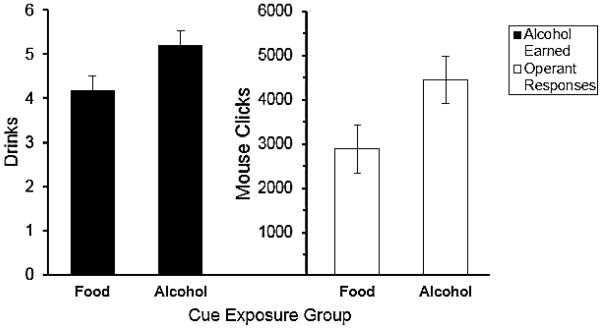

The mean number of drinks earned following cue exposure in each condition is shown in Figure 1. The Figure indicates that those in the alcohol cue exposure condition earned more drinks than those in the food cue condition, and this was confirmed by a t test, t(46) = 2.22, p = .031. Individual differences in drinks earned were evident in each condition. All subjects in each condition worked to earn at least two drinks, and some subjects in each condition worked to earn the maximum of eight drinks. All participants drank all of the beer earned. Figure 1 also presents the mean number of operant responses and shows greater responding by those in the alcohol cue condition compared with the food condition. Examination of participants’ operant responses showed that the scores were positively skewed. The data were log transformed and a t test revealed a significant difference between the conditions, t(46) = 2.49, p = .017. Group differences in drinks earned and operant responding were also analyzed by ANCOVAs that controlled for subjects’ typical quantity of consumption as measured the PDHQ by treating the measure as a covariate. The ANCOVAs also revealed significantly greater operant responding, F(1,45) = 5.54, p = .023, ηp2 = .11, and drinks earned, F(1,45) = 4.16, p = .047, ηp2 = .09, for those in the alcohol cue exposure condition compared with the food cue exposure condition.

Figure 1.

Motivation to consume alcohol. Left panel = mean number of drinks earned during the operant response task; Right panel = total number of operant responses on the operant response task. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

To test the hypothesis that alcohol cues would prime subjects to drink at quantities commensurate with their typical quantities consumed per occasion, the correlation was tested between subjects’ typical quantity of consumption and the amount of alcohol they earned on the operant response task. Results indicated a significant positive relationship between typical quantities and amount of alcohol earned for those exposed to alcohol cues, r(22) = 0.50, p = .014. By contrast, typical quantity of consumption bore no relationship to drinks earned on the operant task following exposure to food cues, r(22) = 0.03, p = .90.

3.3. Cue exposure effects on craving

Table 2 presents mean craving scores for alcohol and for food before and after cue exposure in each condition. Craving levels for alcohol were low regardless of cue exposure. A 2 (cue condition) X 2 time (pre- and post-cue exposure) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of cue condition, F(1,46) = 4.49, p = .040, ηp2 = .09, as those in the alcohol cue condition reported slightly higher levels of craving at each time point compared with those in the food cue condition. However, alcohol cue exposure did not increase craving as Table 2 shows no appreciable change in craving from pre- to post cue exposure.

Table 2.

Cue Exposure Effects on Craving for Alcohol and for Food

| Pre-cue Exposure | Post-cue Exposure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | |

| Alcohol cue exposure | ||||

| Alcohol craving | 2.0 | (2.3) | 2.3 | (2.3) |

| Food craving | 4.4 | (2.5) | 4.6 | (2.4) |

| Food cue exposure | ||||

| Alcohol craving | 1.1 | (1.6) | 0.9 | (1.4) |

| Food craving | 3.4 | (2.4) | 5.0 | (3.0) |

Alcohol craving = craving for alcohol on a 10-point scale ranging from 0 “not at all” to 10 “very much” pre- and post-cue exposure; Food craving = craving for food on a 10-point scale ranging from 0 “not at all” to 10 “very much” pre- and post-cue exposure.

Food craving scores were generally higher and increased in response to the food cue exposure but not to the alcohol cue exposure. This observation was confirmed by a 2 (cue condition) X 2 time (pre- and post-cue exposure) ANOVA of food craving scores which revealed a significant cue condition X time interaction, F(1, 46) = 9.59, p = .003, ηp2 = .17. Examination of the interaction indicated that craving for food increased in response to food cues, t(23) = 4.45, p < .001, but not in response to alcohol cues (p = .46).

4. Discussion

The present study examined the effects of alcohol cue exposure on motivation to consume alcohol following an operant response task in a sample of non-dependent, social drinkers. Results indicated that subjects exposed to alcohol cues displayed greater operant responding and earned more drinks than those exposed to non-alcohol (i.e., food) cues. The cue-induced drinking effect was also evident after controlling for the subjects’ typical quantity of alcohol consumed outside the laboratory. In accord with the hypothesis, the study also showed that when exposed to alcohol cues, but not food cues, subjects worked to earn and consume an amount of alcohol that was related to the amount of alcohol they typically consume outside the laboratory. With regard to craving, the study showed that craving for alcohol was low and was not affected by exposure to alcohol cues, whereas food craving was increased by exposure to food cues.

The findings that exposure to alcohol cues primed social drinkers to drink an amount of alcohol generally commensurate with their typical drinking habits and not necessarily in excess, could account for why research often fails to find evidence for pronounced increases in alcohol consumption in response to alcohol cues in social drinkers (Tiffany, 2000). Although our findings demonstrate that exposure to alcohol cues did prime alcohol consumption in non-dependent drinkers, their consumption was not excessive, as many subjects did not earn the maximum amount of alcohol available to them, but rather earned and consumed amounts similar to their own typical quantity of alcohol consumed per occasion. Thus, the study provides evidence that exposure to alcohol cues might not lead social drinkers to increase their overall consumption, but rather prime them to engage in consuming a quantity of alcohol similar to what they would consume in a natural drinking environment (e.g., pub or restaurant). With regard to the degree of similarity in quantity consumed, it is recognized that the beverage sizes of the drinks in the lab were smaller than typical standard drinks (5 oz vs. 12 oz drinks). However, supplemental analyses compared the total volumes that subjects consumed in the lab with self-reports of their typical quantities, and showed that on average, subjects’ lab consumption was 66% of the amount they typically consume outside the lab. As such, there is some evidence to support the notion that the alcohol cues in this study primed subjects to drink as they would outside the lab.

The self-reports of craving for alcohol also provide corroborating evidence that alcohol-cues do not elicit intense desire for alcohol in non-dependent drinkers. Craving for alcohol was low and unaffected by exposure to alcohol cues. Thus, craving was not a factor in determining motivations to drink in the current study. The finding fits well with a growing body of research which indicates that craving does not reliably precede consumption in social drinkers or relapse in alcoholics (e.g., Drummond, Litten, Lowman, & Hunt, 2000; Ludwig, Wikler & Stark, 1974; Rohsenow & Monti, 1999). It is also unlikely that methodological factors could account for the failure to observe cue-induced increases in alcohol craving. It might be argued that stimulus images of alcohol are insufficient to evoke craving or that our measure of craving was insensitive. However, the same stimulus exposure methods and measures were used to expose subjects to food cues which reliably increased self-reported craving for food. Taken together, the current study shows that alcohol cues can prime subjects to drink in the laboratory at levels similar to the subject’s drinking habits, without necessarily inducing any craving for alcohol, at least when measured by conventional Likert-type craving scales.

A major strength of the current study worth highlighting is the use of an operant task to measure motivation for alcohol as work output. Operant response tasks are commonly used in studies of self-administration in animal models (Willner, Field, Pitts, & Reid, 1998) and have been successfully employed in studies examining alcohol self-administration in humans (e.g., Fillmore 2001; Fillmore & Rush, 2001). It is specifically the work requirement for alcohol that could provide a better indication of priming motivation to drink compared with ad libitum measures in which alcohol is freely available to consume. In ad libitum access measures, such as taste-rating tasks, subjects could consume large amounts simply because it is readily available and not necessarily because they are strongly motivated to do so. The operant response task used in the current study required a sustained period of a monotonous activity (mouse clicking) to earn a drink with a progressive increase in the work required for each drink earned. Thus, it is difficult to dismiss motivation to drink as a key factor that determines the quantity of alcohol consumed in this laboratory measure of drinking behavior.

The current study is not without limitations. First, while the current study focused on individual differences in participants’ drinking habits, it is recognized that other individual difference factors, such as mood, stress, or other personality traits, could likely play a role in cue-induced drinking behaviors. The use of a between-subjects design only allowed for the testing on the effects of one type of cue (i.e., alcohol or food) on alcohol consumption in each individual. Thus, future studies employing within-subjects designs would benefit from increased power by being able to test if alcohol cues lead to increased drinking compared to food cues in each participant. The nature of the operant response task allowed participants to earn a limited number of alcohol servings. Given that participants’ drinking habits indicate typical quantities above this maximum, and the fact that some participants in each cue condition earned the maximum amount of alcohol (i.e., 8 beer servings), increasing the total number of alcoholic beverages participants could earn could better model the relationship between naturalistic drinking and cue-induced drinking in the laboratory.

In conclusion, the findings provide general support for the notion that, relative to non-substance cues, alcohol cues can increase motivation to consume alcohol, and highlight the importance of recognizing that non-dependent drinkers might be unlikely to drink excessively in response to alcohol cues that can prime such excessive drinking in alcohol abusers or other problem drinkers, such as binge drinkers. Rather, for non-dependent drinkers, cue-induced drinking in the lab might resemble the subjects’ typical drinking behavior outside the lab and not necessarily excessive consumption. The findings also add to a growing body of research that questions the role of craving as a precipitating factor in the motivation to drink. The study also demonstrates the feasibility and utility of operant tasks to assess motivation to drink in the laboratory. Operant response models might be particularly useful in studies that examine how alcohol cues might interact with specific characteristics of a drinker to motivate drinking and possibly contribute to the transition from moderate to frequent drinking or to relapse following a period of abstinence in problem drinkers.

Highlights.

Motivation to drink after cue exposure was measured with an operant response task

Social drinkers drank in accordance with their typical drinking habits

Alcohol cues may not lead to excessive consumption in non-dependent drinkers

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This research was funded by NIAAA grant R01 AA018274 and NIDA grant T32 DA035200. These agencies had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Contributors

Both authors designed the study, wrote the protocol, collected the data, and undertook the statistical analyses. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Beirness D, Vogel-Sprott M. Alcohol tolerance in social drinkers: Operant and classical conditioning effects. Psychopharmacology. 1984;84:393–397. doi: 10.1007/BF00555219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BL, Tiffany ST. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction. 1999;94:327–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney NL, Baker LH, Pomerleau OF, Josephy B. Salivation to drinking cues in alcohol abusers: Toward the validation of a physiological measure of craving. Addictive Behaviors. 1984;9:91–94. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(84)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond DC. What does cue-reactivity have to offer clinical research? Addiction. 2000;95:129–144. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond DC, Litten RZ, Lowman C, Hunt WA. Craving research: future directions. Addiction. 2000;95:247–255. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Duka T. Cues paired with a low dose of alcohol acquire conditioned incentive properties in social drinkers. Psychopharmacology. 2002;159:325–334. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0923-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT. Cognitive preoccupation with alcohol and binge drinking in college students: alcohol-induced priming of the motivation to drink. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Rush CR. Alcohol effects on inhibitory and activational response strategies in the acquisition of alcohol and other reinforcers: priming the motivation to drink. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2001;62:646. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Bergquist KL, Hong KI, Sinha R. Stress-Induced and Alcohol Cue-Induced Craving in Recently Abstinent Alcohol-Dependent Individuals. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison EL, Fillmore MT. Are bad drivers more impaired by alcohol?: Sober driving precision predicts impairment from alcohol in a simulated driving task. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2005;37:882–889. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison EL, Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT. Driver training conditions affect sensitivity to the impairing effects of alcohol on a simulated driving test to the impairing effects of alcohol on a simulated driving test. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:588. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.6.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RF, Cooney NL, Baker LH, Gillespie RA, Meyer RE, Pomerleau OF. Reactivity to alcohol-related cues: physiological and subjective responses in alcoholics and nonproblem drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1985;46:267. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1985.46.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberg JC, Hugdahl K, Stormark KM, Nordby H, Aas H. Effects of visual alcohol cues on alcoholics’ autonomic arousal. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1992;6:181. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig AM, Wikler A, Stark LH. The first drink: Psychobiological aspects of craving. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1974;30:539–547. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760100093015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Mendelson JH. Operant analysis of drinking habits of chronic alcoholics. Nature. 1965;206:43–46. doi: 10.1038/206043a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson JH, Mello NK. Experimental analysis of drinking behavior of chronic alcoholics. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1966;133:828–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1966.tb50930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Cooney NL, Kadden RM, Gaupp L. Reactivity to alcohol cues and induced moods in alcoholics. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15:137–146. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90017-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Binkoff JA, Abrams DB, Zwick WR, Nirenberg TD, Liepman MR. Reactivity of alcoholics and nonalcoholics to drinking cues. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1987;96:122. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Rubonis AV, Niaura RS, Sirota AD, Colby SM, Abrams DB. Alcohol cue reactivity: effects of detoxification and extended exposure. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1993;54:235. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan PE, O’Brien JS, Lowenstein LM. Operant studies of chronic alcoholism: Interaction of alcohol and alcoholics. Biological aspects of alcohol. 1971:341–370. [Google Scholar]

- Newlin DB. Conditioned compensatory response to alcohol placebo in humans. Psychopharmacology. 1986;88:247–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00652249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaura RS, Rohsenow DJ, Binkoff JA, Monti PM, Pedraza M, Abrams DB. Relevance of cue reactivity to understanding alcohol and smoking relapse. Journal of abnormal psychology. 1988;97:133. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM. Does urge to drink predict relapse after treatment? Alcohol Research and Health. 1999;23:225–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML, Vinokur A, van Rooijen L. A self-administered short Michigan alcoholism screening test (SMAST) Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1975;36:117–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford D, LeSage MG, Glowa JR. Progressive-ratio schedules of drug delivery in the analysis of drug self-administration: a review. Psychopharmacology. 1998;139:169–184. doi: 10.1007/s002130050702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger PK, White JM. Conditioned alcohol-like and alcohol-opposite responses in humans. Psychopharmacology. 1988;95:87–91. doi: 10.1007/BF00212773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST. Evaluating relationships between craving and drug use. Addiction. 2000;95:1106–1107. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.957110613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Conklin CA. A cognitive processing model of alcohol craving and compulsive alcohol use. Addiction. 2000;95:145–153. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P, Field M, Pitts K, Reeve G. Mood, cue and gender influences on motivation, craving and liking for alcohol in recreational drinkers. Behavioural Pharmacology. 1998;9:631–642. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199811000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]