Abstract

Background

With an aging global population comes significant non-communicable disease burden, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). An unknown proportion of this burden is treatable with surgery. For health system planning, this study aimed to estimate the surgical needs of individuals over 50 years in Nepal.

Methods

A two-stage, cluster randomized, community-based survey was performed in Nepal using the validated Surgeons OverSeas Assessment of Surgical Need (SOSAS) tool. SOSAS collects household demographics, randomly selects household members for verbal head-to-toe examinations for surgical conditions and completes a verbal autopsy for deaths in the preceding year. Only respondents older than 50 years were included in the analysis.

Results

The survey sampled 1,350 households, totaling 2,695 individuals (97% response rate). Of these, 273 surgical conditions were reported by 507 persons ages ≥50 years. Extrapolating, there are potentially 2.1 million people over age 50 with surgically treatable conditions needing care in Nepal (95%CI 1.8 – 2.4 million; 46,000 – 62,6000 per 100,000 persons). One in five deaths were potentially treatable or palliated by surgery. Though a growth or mass (including hernias and goiters) was the most commonly reported surgical condition (25%), injuries and fractures were also common and associated with the greatest disability. Literacy and distance to secondary and tertiary health facilities were associated with lack of care for surgical conditions (p<0.05).

Conclusion

There is a large unmet surgical need among the elderly in Nepal. Low literacy and distance from a capable health facility are the greatest barriers to care. As the global population ages, there is an increasing need to improve surgical services and strengthen health systems to care for this group.

Keywords: Aging, surgical capacity, Nepal, low-income, community assessment

Introduction

The rate of global population aging is without parallel in human history. By mid-century, there will be more than two billion people over 60 years of age.[1] The majority of elderly will live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with health-systems least equipped to care for their unique health needs.[1, 2]

With aging populations comes a marked rise in non-communicable diseases (NCDs). In the next decade, the NCD burden will surpass that of infectious, maternal, perinatal and nutritional diseases combined.[3] Given that a significant proportion of NCDs are at least partially treatable with surgery, the importance of surgery in global public health can no longer be ignored.

Surgical care for the elderly differs from care of younger individuals in several different ways. Older persons are more likely to present with emergencies, have comorbid illnesses and malignancies.[4] They more often require critical care, prolonged hospitalizations and rehabilitation.[5, 6] In addition, with advanced age comes the need for end-of-life care goals, including palliation. Providing consistent access to these services requires significant resources, expertise and planning.

Individuals living in LMICs have poor access to surgical care.[7, 8] Of an estimated 234 million major operations performed a year, only 3.5% occur in low resource countries despite having 35% of the world’s population.[9] Since most people in LMICs with surgical conditions never reach a health facility, estimates of surgical need from hospital-based data have limited generalizability.[10, 11] Therefore, community surveys of surgical need are more appropriate for describing unmet surgical needs in these settings.

Nepal is a low-income country with a gross national income per capita of US$ 730 and a rapidly aging population and a significant burden of NCDs.[12] The life expectancy at birth and age 60 is 68 and 17 years, respectively. To aid planning for health-system strengthening in Nepal and other LMICs, a two-stage, cluster randomized survey was done to quantify the prevalence of surgical need.[13] This study details surgical disease reported by those 50 years of age and older.

Methods

Survey tool

The Surgeons OverSeas Surgical Assessment Survery (SOSAS) is a validated, cluster randomized, cross sectional, countrywide survey that identifies potentially treatable surgical conditions (curative or palliative). Detailed methods have been previously reported.[10, 13, 14] Briefly, heads of randomly selected households are interviewed for household demographics and deaths attributable to lack of surgical care in the preceding year. Then, two household members are randomly selected to participate in a verbal examination of six anatomic regions: 1) face, head and neck; 2) chest and breast; 3) abdomen; 4) groin and genitalia; 5) back and 6) extremities. History and symptoms are verbally elicited for wounds (due to injury or non-injury causes), burns, masses, deformities and other surgical conditions specific to anatomic regions. ‘Non-injury wound’ identifies conditions such as Buruli, tropical, venous stasis, diabetic, or ischemic ulcers, draining osteomyelitis, advanced cutaneous cancers, enteroatmospheric fistulas, etc.

Setting

Nepal is a low-income country in South Asia with 27.8 million inhabitants transitioning from a decade-long conflict that ended in 2006.[15] Political unrest has left the national healthcare system fragile, under-resourced and unable to adequately care for the population’s disease burden.[12] In addition, Nepal’s rugged terrain and deficiencies in infrastructure limit access to healthcare for much of the population.[16] To temper this challenge, the national health system has many primary care providing facilities and relatively few secondary and tertiary care facilities. This referral hierarchy is designed to ensure the majority of the population has access to public health and primary care. [17] Nepal has five development regions subdivided into 75 districts. Within districts are 3,915 administrative units called Village Development Committees (VDCs).[18]

Data collection

Two-stage cluster sampling was performed from May 25 to June 12, 2014. Fifteen districts were randomly selected proportional to population and then forty-five VDCs (three per district) were randomly selected after stratification of urban and rural populations (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of Nepal demonstrating communities surveyed with SOSAS tool.

One hundred Nepali interns and students from Kathmandu Medical College, College of Medical Sciences in Bharatpur, B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences in Dharan and Manipal College of Medical Sciences in Pokhara were trained as enumerators. Training included explanation of the survey, theoretical sessions and field practicals.

In each VDC, interviewers began at a central location and sampled every 5th household. Thirty households per VDC were selected for a total sample size of 1,350 households. Sample size estimation was established during the pilot study where the prevalence of unmet surgical need was 5%.[13] All surveys were administered in Nepali and responses recorded in English using paper surveys. Daily, supervisors reviewed all data for adequacy and accuracy and reported to the project supervision for feedback.

Data analysis

Proportions and confidence intervals were calculated with Taylor-linearized variance estimation. For the calculations, the primary sampling unit was the district and secondary sampling unit the VDC. The inverse probability of being sampled from both the district and VDC were applied as sampling weights. Mann-Whitney’s U test was used to compare those who had and had not received care for their condition across continuous transport variables. Odds ratios were calculated using a three-level mixed-effects logistic regression model to control for intra-class correlation within district and VDC clusters and within rural and urban strata. An adjusted model included age, sex and literacy, covariates thought to be related to surgical need a priori.

Potential surgical gap is the proportion of respondents who reported currently having a condition potentially treatable with surgery and not receiving care due to financial needs, inaccessible health facilities or lack of healthcare capacity. Growths, masses, hernias and goiters are grouped due for verbal diagnostic ease but differentiated by region. Having a palpable or reducible mass from within the vagina is used as a proxy for pelvic organ prolapse in this age group. Death rates were calculated using population and age structure estimates from the World Bank and the Nepal Central Bureau of Statistics.[15] All analyses were performed with Stata 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, 2013).

Ethics and funding

Ethical review boards from the Nepal Health Research Council in Kathmandu and Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, USA provided approval. Heads of household and household members gave verbal consent prior to interview. Mentally disabled or cognitively impaired household members were not included in this assessment of surgical need.

Logistical and transportation funding was provided by the 2014 Global Surgery Research Fellowship Award provided by the Association for Academic Surgery and from Surgeons OverSeas (SOS), a United States-based non-governmental organization.

Results

The survey sampled 1,350 households, totaling 2,695 individuals (97% response rate). Of these, 507 were over the age of 50 (49% 50-59, 33% 60-69 and 17% ≥70 years). Around half of those ages 50-59 were literate while only a third of those 60 years or older were able to read. Eight percent of respondents in their 6th decade were retired or unemployed compared to more than half of those aged ≥70 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents aged at least 50 years in Nepal.

| Total (≥50 years) |

Aged 50 - 59 years |

Aged 60 - 69 years |

Aged ≥70 years |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 95% CI* | n (%) | 95% CI* | n (%) | 95% CI* | n (%) | 95% CI* | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 272 (54) | 48.7 - 58.5 | 137 (55) | 44.7 - 65.0 | 84 (50) | 45.1 - 54.9 | 51 (57) | 47.0 - 65.8 |

| Female | 235 (46) | 41.5 - 51.3 | 112 (44) | 35.0 - 55.4 | 84 (50) | 45.1 - 54.9 | 39 (43) | 34.1 - 53.0 |

| Literate | ||||||||

| Unable to read | 297 (59) | 49.5 - 67.1 | 118 (47) | 35.1 - 60.0 | 118 (70) | 62.5 - 77.1 | 61 (68) | 58.1 - 76.2 |

| Able to read | 210 (41) | 32.9 - 50.5 | 131 (53) | 40.0 - 64.9 | 50 (30) | 23.0 - 37.6 | 29 (32) | 23.8 - 42.0 |

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Retired, unemployed | 115 (23) | 19.0 - 26.9 | 21 (8) | 5.2 - 13.5 | 46 (27) | 20.0 - 36.3 | 48 (53) | 39.7 - 66.5 |

| Homemaker | 145 (29) | 24.8 - 32.8 | 79 (32) | 24.9 - 39.4 | 46 (27) | 20.1 - 36.1 | 20 (22) | 13.5 - 34.3 |

| Domestic employee | 11 (2) | 1.3 - 3.4 | 4 (2) | 0.6 - 4.4 | 5 (3) | 1.5 - 5.7 | 2 (2) | 0.6 - 8.2 |

| Farmer, pastoralist | 120 (24) | 14.6 - 36.1 | 62 (25) | 14.4 - 39.6 | 43 (26) | 15.0 - 40.1 | 15 (17) | 6.7 - 35.9 |

| Self-employed | 81 (16) | 11.3 - 22.1 | 53 (21) | 14.1 - 30.8 | 24 (14) | 9.2 - 21.6 | 4 (4) | 2.1 - 9.3 |

| Government, professional | 35 (7) | 4.1 - 11.3 | 30 (12) | 7.8 - 18.2 | 4 (2) | 9.4 - 5.9 | 1 (1) | 0.1 - 8.3 |

CI – confidence intervals

Seventy-eight percent of respondents walked to primary healthcare facilities and used public transport for getting to secondary (67%) and tertiary facilities (85%). Distance to secondary and tertiary health facilities was associated with not receiving care for potentially surgical conditions (p<0.05). Travel to tertiary facilities that have specialist surgeons was prohibitively expensive for 25% of households despite costing less than US$ 3.00 most of the time (p<0.05) (Table 2). There was no evidence of an association between decade of life, gender or residence and having at least one surgical condition among those at least 50 years of age. Literates had less odds of having a surgical condition compared to those who could not read (aOR 0.71, 95%CI 0.59 – 0.85) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of type, time and cost of transport to health facilities reported by respondents aged at least 50 years in Nepal.

| Health facility |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | Tertiary | |

| Mode, n (%) | |||

| Public | 69 (13) | 337 (67) | 427 (85) |

| Car | 6 (1) | 19 (4) | 20 (4) |

| Motorcycle | 27 (5) | 37 (7) | 32 (6) |

| Bicycle | 8 (2) | 6 (1) | 0 |

| Foot | 396 (78) | 106 (21) | 26 (5) |

| Wait for transport time, med (IQR) * | 0 (0) | 10 (0 - 30)† | 20 (10 - 60)† |

| Travel time, med (IQR) | 14 (5 - 20) | 60 (20 - 180)† | 120 (30 - 240)† |

| Travel cost, med (IQR) | 0 (0) | 0.59 (0 - 3.58) | 2.56 (0.56 - 10.23)† |

| Unable to afford transport, n (%) | 2 (1) | 72 (14) | 129 (25)† |

Time is in minutes, med – median, IQR – interquartile range;

p<0.05 for those of each covariate who have a surgical condition potentially treatable with surgery who have received care compared to those who have not.

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios for demographic covariates and having at least one surgical condition.

| No surgical condition; n (%) |

At least one surgical condition; n (%) |

Adj.* odds ratio |

95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||||

| 50 - 59 years | 120 (48) | 129 (52) | Referent | |

| 60 - 69 years | 76 (45) | 92 (55) | 1.18 | 0.79 - 1.79 |

| ≥70 years | 38 (42) | 52 (58) | 1.29 | 0.77 - 2.18 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 136 (50) | 136 (50) | Referent | |

| Female | 98 (42) | 137 (58) | 0.96 | 0.81 - 1.13 |

| Residency | ||||

| Urban | 75 (44) | 97 (56) | Referent | |

| Rural | 159 (48) | 176 (52) | 0.86 | 0.66 - 1.13 |

| Literacy | ||||

| Unable to read | 134 (45) | 163 (55) | Referent | |

| Able to read | 100 (48) | 110 (52) | 0.71 | 0.59 - 0.85 |

Adj. – adjusted odds ratios were calculated using a three-level mixed-effects logistic regression model to control for intra-class correlation within district and VDC clusters and within rural and urban strata. The model also incorporated age, sex and literacy; CI – confidence interval

There were 273 conditions potentially treatable with surgery were reported. Eight percent of respondents reported 2 conditions, 1.6% reported 3 conditions and 0.4% reported 3 conditions. Of these, 66% were prevalent and 51% have been present for more than a year. Extrapolating, there are potentially 2.1 million people over age 50 with surgically treatable conditions needing care in Nepal (95%CI 1.8 – 2.4 million; 46,000 – 62,6000 per 100,000 persons). Eight percent sought care from a traditional healer. More than 40% of those potentially in need of surgery have not received consultation or care for their condition. This was most commonly due to insufficient healthcare services (41%), unaffordable care (25%), fear or distrust (25%) and other reasons (Table 4).

Table 4.

Conditions potentially treatable with surgery and care received among those aged at least 50 years in Nepal.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Any surgical condition | ||

| 50 - 59 years | 129 | (52) |

| 60 - 69 years | 92 | (55) |

| ≥70 years | 52 | (58) |

| Type of care received | ||

| Traditional healer | 23 | (8) |

| Minor | 34 | (13) |

| Major | 72 | (26) |

| If no care, why? | ||

| Care unaffordable | 28 | (25) |

| Not available | 46 | (41) |

| Fear or lack of trust | 28 | (25) |

| No time | 11 | (9) |

| Current surgical gap * | ||

| Patients | 94 | (58) |

Current surgical gap represents patients who reported having a condition potentially treatable with surgery, not receiving care and reporting need. This excludes respondents who have seen a care provider about the condition and told that it does not require surgery. It also excludes those with a surgical condition but not perceived as one.

There were 108 deaths in the year prior to the survey. Twenty (19%) were potentially preventable with surgery. Half of the deaths were due to a growth or mass, 20% to injury, 20% to abdominal pain or distension and 10% to a non-injury wound. The age-standardized death rate of those with a potentially surgical condition was 24, 60 and 44 per 1,000 persons for individuals in their 6th, 7th and 8th or more decade of life, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Deaths, number of conditions by anatomic region among those aged at least 50 years in Nepal.

| Death |

Number of conditions reported |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | Head and neck |

Chest and breast |

Abdomen | Groin and genitalia |

Back and extremities |

|

| Surgically treatable | 20 | (19) | |||||

| Injury, fracture | 4 | (20) | 15 | 1 | 57 | ||

| Non-injury wound | 2 | (10) | 9 | 1 | 12 | 10 | |

| Burn | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| Growth, mass, goiter, hernia | 10 | (50) | 28 | 6 | 19 | 12 | 26 |

| Abdominal pain/distension | 4 | (20) | 16 | ||||

| Congenital deformity | 6 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Acquired deformity | 29 | 20 | |||||

| Urinary retention, hematuria | 10 | ||||||

| Rectal bleeding | 4 | 11 | |||||

| Incontinence | 41 | ||||||

| Pelvic organ prolapse, mass | 27 | ||||||

| Non-surgically treatable or unknown | 88 | (81) | |||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Total; n (%) | 108 | 88 (24) | 9 (2) | 51 (14) | 102 (28) | 120 (32) | |

Though a growth or mass (including hernias and goiters) was the most commonly reported potentially surgical condition (25%), injuries and fractures were also common and had the greatest disability. Acquired deformities (13%), incontinence (11%), non-injury wounds (9%) and pelvic organ prolapse were also prevalent. Back and extremity conditions (32%) were responsible for most conditions potentially treatable with surgery, followed by genitourinary (28%), head and neck (24%), abdominal (14%) and chest and breast conditions (2%) (Table 5).

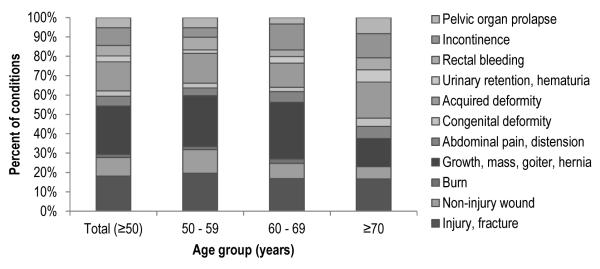

From the 6th to the ≥8th decade non-injury wounds, growths and masses and rectal bleeding decreased by half. Conversely, the prevalence of abdominal pain and distension, urinary retention, incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse increased substantially (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of conditions potentially treatable with surgery reported by those aged at least 50 years in Nepal.

Discussion

There are potentially more than 2.1 million adults 50 years and older with a surgically treatable condition in Nepal. Currently, nearly one in five deaths may be due to a condition that would benefit from surgical treatment or palliation in this age group. Transportation and care costs, limited access to surgical services and under-resourced facilities have created a large gap of unmet surgical need comprising more than 40% of those over 50 years in age. With a rapidly aging population, Nepal will certainly witness an increase in this large burden.

Providing surgical care for the aged is challenging, particularly for LMIC health systems. Age independently, delayed diagnosis, frequent emergency presentation, co-morbid illness and baseline frailty contribute to significantly higher rates of perioperative morbidity and mortality in elderly requiring surgery.[4, 5, 19] To combat these risks and address disparate surgical needs, care of the elderly requires expert multidisciplinary teams, specialist surgeons and capacity for palliative care, prolonged hospital stays and rehabilitation services.[5, 19-21] Subsequently, high use of healthcare resources among the aged is common.[21] With LMICs’ limited capacity for surgical care at baseline, the added pressures of elderly needs strain health systems even further. With rapidly aging populations, LMICs are confronted with a significant unmet burden of surgical disease. This is evidenced by more than 40% of the elderly in Nepal currently with a condition potentially treatable with surgery. SOSAS Sierra Leone found a similar prevalence of surgical disease in those aged at least 50 years, suggesting this is not a nationally- or regionally-specific finding.[22] Given the anticipated disproportionate demographic transition in LMICs, efforts to provide sustained relief of this unmet surgical need are imperative.

Fundamental to reducing unmet surgical need is ease of access to care and appropriate capacity.[23] In addition to being a low-income country with a paucity of well-maintained transit infrastructure, Nepal has a predominantly rural population living in a rugged terrain.[16] Consequently, travel distance and cost are significant barriers to accessing surgical care that is predominantly performed in secondary and tertiary health facilities distant from much of the population. A quarter of the elderly are not able to afford transportation to tertiary facilities for surgical consultation or care. Of the individuals who were able to afford care but did not undergo intervention, 41% reported that the appropriate services are not available for treatment. These barriers to care are not unique to Nepal.[24-26] Several frameworks have been proposed to improve access to care and tackle the multi-dimensionality of improving non-communicable disease treatment and, specifically, surgical capacity in LMICs.[23, 27, 28] Paramount to improving access to surgical care for the majority of the population is strengthening district hospital capacity for safe surgery.[29, 30] Providing surgical care for conditions accounting for a sizable portion of unmet surgical need has proven feasible and cost effective, yet is not often discussed as a health system priority.[31, 32] Consistent, dedicated national strategies are required to aid health systems transition from vertical healthcare delivery designed for the HIV, tuberculosis and malaria epidemics to integrated systems now charged with controlling the colossal burden of NCDs. Previous surgical needs assessments have relied on hospital-based data.[33-35] Given patients in LMICs face insufficient healthcare infrastructure, are often unable to afford transportation or care, mistrust surgical services and often die before reaching a hospital, these assessments have grossly underestimated the volume of global unmet surgical need.[24, 33, 36] Estimates of the burden of surgical disease are not the same between LMICs.[4, 34] SOSAS Sierra Leone reported 71% and 33% of those ≥50 years of age having had or dying from a potentially surgical condition, respectively.[22] Compare this to 54% and 19% in Nepal. Though in proportional terms these are not markedly different, when extrapolated nationally they represent a difference of hundreds of thousands of persons. Further, both of these countries are small (Sierra Leone 6.1 million, Nepal 27.8 million). If surgical capacity improvement interventions in more populous countries, such as Indonesia with 252 million persons or Nigeria with 179 million persons, relied on estimates from other LMICs, they could misallocate services for tens of millions of patients and potentially waste critically limited resources.[37] Accurately estimating unmet surgical need is a fledgling topic and its exact determinants are unknown. However, national demographics, population and healthcare facility distribution, surgical epidemiology, income disparity, presence of national insurance schemes, dense penetration of humanitarian aid, presence or absence of current or recent conflict or disaster, trajectory of healthcare investment and other factors may contribute to the exact burden. Resultantly, international extrapolation is difficult and should be done with caution. Therefore, the results of SOSAS are extremely useful to Nepal, allow comparable low-income countries to grossly estimate their burden of surgical disease, continue to build advocacy for support of surgical care in LMICs and provide a baseline from which future capacity improvement interventions can be benchmarked.

The study has a number of limitations. Only 15 of the 75 districts in Nepal were sampled. However, sampling was proportional to population, many districts are mountainous and sparsely populated and the confidence intervals and analyses above are weighted and controlled for the two-stage cluster stratified design to more closely reflect the population of Nepal. To be useful for non-clinicians in LMICs, the survey uses condition definitions that are purposefully simple, to encourage response and avoid confusion. Though not presented here, unique to SOSAS Nepal is a visual physical exam. Verbal responses and exam findings agreed 94.6% of the time (kappa 0.78, 95% CI 0.74 – 0.82), validating the questions’ use as proxies for surgical conditions.[13] Further complicating the survey, some conditions, such as rectal bleeding, do not necessarily require surgery. The survey did not distinguish between medical and surgical conditions with the same clinical presentation, potentially overestimating surgical need. However, most of these cases would likely require at least a surgical consultation, an often-overlooked aspect of surgical capacity development planning. As with all cross-sectional studies of past events, there is an unknown degree of recall bias. Overestimation of tragic deaths and underestimation of unknown or forgotten surgical causes of death and disease are possible. However, the study population had a crude death rate of 6 per 1,000 persons, similar to the 2012 estimate of 7 per 1,000 persons.[38] The age-adjusted death rates from surgical conditions decreased from the 7th to the 8th decade of life. This is likely a reflection of random variation in the low number of reported deaths within each decade (20 deaths over three decades of life) and may not be a precise portrayal of death rates from surgically treatable conditions. Given the scope of the study, further granularity of access to care barriers, care-seeking behaviors and disability information was not sought. However, these data are important for planning health systems strengthening interventions.

Conclusion

There is a large unmet surgical need among the elderly in Nepal. Limited access to care and associated costs frequently prohibit those in need from receiving treatment. In addition to these common difficulties in LMICs, the elderly face additional risks from under-resourced perioperative care devoid of multidisciplinary teams, specialists and rehabilitation. The amelioration of these risks needs to be explicitly considered as further efforts are deployed to improve global surgical capacity.

Acknowledgements

We thank the dedicated supervisors and enumerators for their contribution to understanding surgical need in Nepal. Funding for logistics was provided by the United States based non-governmental organization, Surgeons OverSeas (SOS) and the 2014 Global Surgery Research Fellowship Award provided by the Association for Academic Surgery. Data analysis and manuscript preparation was done with funding from the Fogarty International Center through the Northern Pacific Global Health Research Fellows Training Consortium under grant number R25TW009345.

Sources of funding: Logistical and transportation funding for the survey was provided by the 2014 Global Surgery Research Fellowship Award provided by the Association for Academic Surgery and from Surgeons OverSeas, a United States-based non-governmental organization. Data analysis and manuscript preparation was done with funding from the Fogarty International Center through the Northern Pacific Global Health Research Fellows Training Consortium.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Barclay Stewart, Department of Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Evan Wong, Surgeons OverSeas (SOS), New York, NY, USA Centre for Global Surgery, McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, QC, Canada.

Shailvi Gupta, Surgeons OverSeas (SOS), New York, NY, USA Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Santosh Bastola, Manipal College of Medical Sciences, Pokhara, Nepal.

Sunil Shrestha, Department of Surgery, Nepal Medical College, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Adam Kushner, Surgeons OverSeas (SOS), New York, NY, USA; Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA; Department of Surgery, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Benedict C. Nwomeh, Surgeons OverSeas (SOS), New York, NY, USA Department of Pediatric Surgery, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

References

- 1.Kalache A, Fu D, Yoshida S. In: WHO Global Report on Falls Prevention in Older Age, in Department of Aging and Life Course. Salas-Rojas C, editor. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shetty P. Grey matter: ageing in developing countries. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1285–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60541-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World_Health_Organization . Global status report on non-communicable diseases 2010. WHO; Geneva: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart B, et al. Global disease burden of conditions requiring emergency surgery. Br J Surg. 2014;101(1):e9–22. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown NA, Zenilman ME. The impact of frailty in the elderly on the outcome of surgery in the aged. Adv Surg. 2010;44:229–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes M, et al. Comparison of Two Comorbidity Scoring Systems for Older Adults with Traumatic Injuries. J Am Coll Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watters DA, et al. Perioperative Mortality Rate (POMR): A Global Indicator of Access to Safe Surgery and Anaesthesia. World J Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2638-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ologunde R, et al. Assessment of cesarean delivery availability in 26 low- and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiser TG, et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet. 2008;372(9633):139–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60878-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groen RS, et al. Pilot testing of a population-based surgical survey tool in Sierra Leone. World J Surg. 2012;36(4):771–4. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World_Health_Organization . Guidelines for Conducting Community Surveys on Injuries and Violence. Geneva: 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhandari GP, et al. State of non-communicable diseases in Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta S, et al. Surgical Needs of Nepal: Pilot Study of Population Based Survey in Pokhara, Nepal. World J Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2753-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groen RS, et al. Untreated surgical conditions in Sierra Leone: a cluster randomised, cross-sectional, countrywide survey. Lancet. 2012;380(9847):1082–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nepal_Central_Bureau_of_Statistics [cited 2014 September 8th];Population. District and Municipal Level Report 2014. Available from: http://cbs.gov.np/?cat=7.

- 16.Hodge A, et al. Utilisation of Health Services and Geography: Deconstructing Regional Differences in Barriers to Facility-Based Delivery in Nepal. Matern Child Health J. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [cited 2014 August 4th, 2014];Annual Report, Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Population, Nepal. 2012 Available from: http://phpnepal.org/index.php?listId=453-.U6R7iJSSy2E.

- 18.Ahuja RB, Goswami P. Cost of providing inpatient burn care in a tertiary, teaching, hospital of North India. Burns. 2013;39(4):558–64. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turrentine FE, et al. Surgical risk factors, morbidity, and mortality in elderly patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(6):865–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClellan EB, et al. The impact of age on mortality in patients in extremis undergoing urgent intervention. Am Surg. 2013;79(12):1248–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zenilman ME, et al. New developments in geriatric surgery. Curr Probl Surg. 2011;48(10):670–754. doi: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong EG, et al. Prevalence of Surgical Conditions in Individuals Aged More Than 50 Years: A Cluster-Based Household Survey in Sierra Leone. World J Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2620-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kushner AL. A Proposed Matrix for Planning Global Surgery Interventions. World J Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2748-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimes CE, et al. Systematic review of barriers to surgical care in low-income and middle-income countries. World J Surg. 2011;35(5):941–50. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kingham TP, et al. Quantifying surgical capacity in Sierra Leone: a guide for improving surgical care. Arch Surg. 2009;144(2):122–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.540. discussion 128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mock CN, nii-Amon-Kotei D, Maier RV. Low utilization of formal medical services by injured persons in a developing nation: health service data underestimate the importance of trauma. J Trauma. 1997;42(3):504–11. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199703000-00019. discussion 511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gounder CR, Chaisson RE. A diagonal approach to building primary healthcare systems in resource-limited settings: women-centred integration of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, MCH and NCD initiatives. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(12):1426–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sepulveda J, et al. Improvement of child survival in Mexico: the diagonal approach. Lancet. 2006;368(9551):2017–27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galukande M, et al. Essential surgery at the district hospital: a retrospective descriptive analysis in three African countries. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3):e1000243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luboga S, et al. Increasing access to surgical services in sub-saharan Africa: priorities for national and international agencies recommended by the Bellagio Essential Surgery Group. PLoS Med. 2009;6(12):e1000200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hipgrave DB, et al. Health sector priority setting at meso-level in lower and middle income countries: lessons learned, available options and suggested steps. Soc Sci Med. 2014;102:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grimes CE, et al. Cost-effectiveness of surgery in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2014;38(1):252–63. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2243-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bickler S, et al. Key concepts for estimating the burden of surgical conditions and the unmet need for surgical care. World J Surg. 2010;34(3):374–80. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0261-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lozano R, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozgediz D, et al. The burden of surgical conditions and access to surgical care in low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(8):646–7. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.050435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mock CN, et al. Incidence and outcome of injury in Ghana: a community-based survey. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77(12):955–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World_Bank_Group [cited 2014 July 29];World Development Indicators. GNI per capita: Atlas method. 2014 Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD/countries.

- 38.World_Health_Organization . Demographic and socioeconomic statistics: Crude birth and death rate. WHO; Geneva: 2012. [Google Scholar]