Abstract

Background

Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) enhances infant and maternal well-being and requires maternal-care partnerships (MCP) for implementation.

Objective

To examine maternal and neonatal nurse provider perspectives on the value of KMC and MCP.

Study Design

Prospective cohort design of neonatal nurses and mothers of preterm infants self-report anonymous questionnaire. Analyses of categorical independent variables and continuous variables were calculated.

Results

In all, 82.3% of nurses (42) and 100% (143) of mothers participated in the survey. compared with 18% of nurses, 63% of mothers believed “KMC should be provided daily” and 90% of mothers compared with 40% of nurses strongly believed “mothers should be partners in care.” In addition, 61% of nonwhite mothers identified that “KMC was not something they were told they could do for their infant” compared with 39% of white mothers. Nonwhite and foreign-born nurses were 2.8 and 3.1 times more likely to encourage MCP and KMC.

Conclusion

Mothers held strong positive perceptions of KMC and MCP value compared with nurses. Nonwhite mothers perceived they received less education and access to KMC. Barriers to KMC and MCP exist among nurses, though less in nonwhite, foreign-born, and/or nurses with their own children, identifying important provider educational opportunities to improve maternal KMC access in the NICU.

Keywords: maternal, neonatal nurse, perceptions, kangaroo mother care

Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC), a specific method of care in which the mother is supported to hold her diaper clad infant skin-to-skin upright between her breasts, has been associated with improvements in preterm infant outcome including decreased infant pain sensation and stress, improved breast-feeding success as well as improved preterm infant development and growth in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).1–3 KMC use also enhances maternal well-being and parental satisfaction and decreases risk for postpartum depression.4–6 For mothers with a preterm infant, participation, interest, and education in provision of KMC may be facilitated by NICUs that practice family-centered care (FCC) as a care standard in the NICU.7 FCC creates a locus where parents develop partnerships with nurses, physicians, and care team members to collaborate in the infant’s care.7 The neonatal nurse care structure of nursing assignment combined with the NICU team members form “NICU cultures” of care for all infants. Within this model, the care beliefs of the bedside neonatal nurse impact on the provision of care practices available to the mother and infant.8–10 Often called the “gatekeeper for infant care,” the neonatal nurse is vital to implementation and use of KMC within any given NICU.8–13 In this role, the neonatal nurse also engages and educates parents and provides medical guidance, support, and personal beliefs that inform parents about the culture of NICU care and important infant care methods such as provision of KMC. As parent educators, the neonatal nurse assesses maternal understanding and readiness for KMC implementation and supports the integration of KMC into the infant’s individualized medical care plan in the NICU. Numerous studies have examined the health benefits and effectiveness of the use of KMC.4–6 However, none have examined the nurses’ and mothers’ beliefs related to implementation and perceptions of use of the KMC practice in the NICU despite its positive outcomes. As key aspects of KMC care involves neonatal nurse beliefs for the introduction and integration of KMC in the neonatal care team plans for the infant, the focus of this study was to assess neonatal nurse and mothers perceptions of the value of KMC as well as the perceptions of various aspects of maternal care partnership in the NICU, needed for KMC implementation. Utilizing a survey, we sought to evaluate the concordance of neonatal nursing and mother's perception of value of KMC as well as maternal care partnerships as factors that improve the health of their infants. Specific areas of interest included identifying areas of differences in overall belief between nurses and mothers as well as potential individual nurses and maternal differences that might impact on utilization of the KMC care technique.

Methods

This prospective cohort study was conducted at two hospitals (Bellevue Hospital Center and Tisch Hospital, both located in the borough of Manhattan, New York City) with similar patient care acuity and designation as level-three facilities and leadership staff, and the structure of medical education, care policies, and guidelines were identical. The work was approved by the institutional review board of New York University and Bellevue Hospital. Between 2008 and 2009 all NICU nurses were invited to participate in completing a broader investigation of beliefs related to FCC and KMC utilization in the NICU through an anonymous 24-question survey composed of key KMC questions and beliefs related to the value of including parents as care team members. Additionally, mothers whose discharged infants were < 34 weeks’ gestation and in the NICU during that same time period (2008 to 2009) were asked to participate in the nursing survey in which the questions were adapted for mothers.

The questionnaire measured attitudes and beliefs regarding FCC parental partnerships and KMC by determining the strength of agreement or disagreement on a 5-point rating scale for 24 statements that had been used previously.14 The 5-point rating scale included: 1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = neither agree or disagree, 4 = disagree, and 5 = strongly disagree. Specific nursing personal demographic characteristics such as age, race, ethnicity, gender, and place of birth as well as nursing training level were collected for the nursing populations by self-report. Identical maternal personal demographic characteristics were collected by self-report. Participants could also include comments in the survey. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained to conduct this survey (IRB Study # 07–354). Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS for Windows, Version 17 (Chicago, IL). Characteristics of the women from both cohorts were compared using chi-square tests. Data were analyzed for neonatal nursing and maternal strength of beliefs related to KMC and specific FCC questions. Fisher exact test, Pearson chi-square test, independent samples t test, one-way analysis of variance were used for statistical analyses of categorical independent variables and continuous variables.

Results

Forty-two of 51 eligible neonatal nurses (82.3%) participated in the survey. One hundred forty-three mothers were invited to participate and all completed the survey. No mother refused to participate in the survey. All mothers who completed the survey were mothers of inborn admissions. All nurses worked in a level III NICU facility designated as a New York State regional perinatal center accredited to care for the highest level of maternal and infant acuity. Neonatal nurses and mothers did not differ significantly in their age but differed in the composition of their race/ethnicity (p < 0.05), place of birth (p < 0.05), years living in the United States (p < 0.05), and number with children (p < 0.01, ▶Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Nurses and Mothers who Participated in the Survey (n = 185)

| Characteristics | Nurses (n = 42) | Mothers (n = 143) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity, n (%)a | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 12 (28.5) | 60 (41.9) | 0.029* |

| Hispanic | 4 (9.5) | 17 (11.8) | |

| Asian/other | 21 (50.0) | 55 (38.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 5 (11.9) | 11 (7.6) | |

| Gender, n (%)a | |||

| Male | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Female | 40 (95.2) | 143 (100) | |

| Place of birth | |||

| U.S. born, n (%)a | 14 (33.3) | 97 (67.8) | 0.030* |

| Non-U.S. born, n (%)a | 18 (66.7) | 46 (32.1) | |

| Age, mean (SD)b | 38.9 (8.4) | 31.6 (5.8) | 0.758 |

| Years living in U.S., mean (SD)b | 20.9 (7.9) | 12.1 (7.8) | 0.015* |

| Years of work experience, mean (SD)b | 15.5 (8.9) | NA | |

| No. with children, n (%)a | 18 (42.9) | 143 (100) | < 0.001* |

Pearson Chi-Square Test

Independent samples t-test

Statistically significant

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation.

Perceptions of Mothers as Care Partners in the NICU

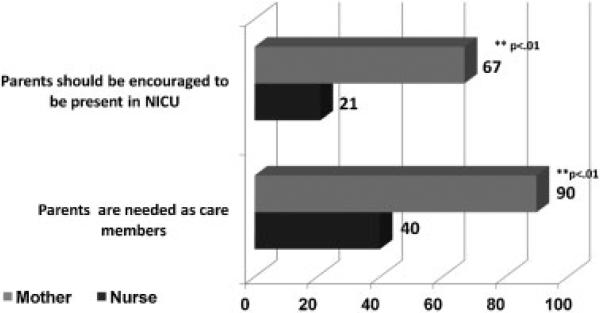

The “value of parental presence in the NICU,” a particular hallmark of FCC, notably differed between nurses and mothers with 21% of nurses strongly agreeing that they should encourage parental presence compared with 67% of mothers (p < 0.01, ▶Fig. 1). When asked “Parents come to see their infant because they know they are needed in helping their baby get healthy,” 40% of nurses strongly held this belief compared with 87.7% of mothers (p < 0.01, ▶Fig. 1). However, nonwhite and foreign-born nurses differed in their strength of belief of parental presence in the NICU compared with white nurses (odds ratios of 2.8 and 3.1, respectively; ▶Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Nurses’ and mothers’ beliefs related to parents role in the NICU. Nurses and mothers strongly agreed in responses to questions on parental roles. Statistical significance: **p < 0.01. Abbreviation: NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Table 2.

Effect of Race and Foreign-born Status on Nurse's Responsea

| Questions and likelihood of agreeing | Nurse characteristics | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Parents should be encouraged to come to the NICU anytime | Nonwhite | 2.77 (1.07–7.21) |

| Foreign-born | 3.12 (1.23–7.87) | |

| Kangaroo care is offered in every NICU | Nonwhite | 3.04 (1.05–8.76) |

| Foreign-born | 3.87 (1.49–10.66) | |

| I introduce KMC on the first day | Nonwhite | 2.77 (1.07–7.21) |

| Foreign-born | 3.12 (1.23–7.87) | |

| KMC should be started right after birth | Have children | 9.00 (1.14–71.04) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; KMC, Kangaroo Mother Care; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

The nurse's likelihood of agreeing with parental presence in the NICU and KMC questions based on racial and foreign-born status.

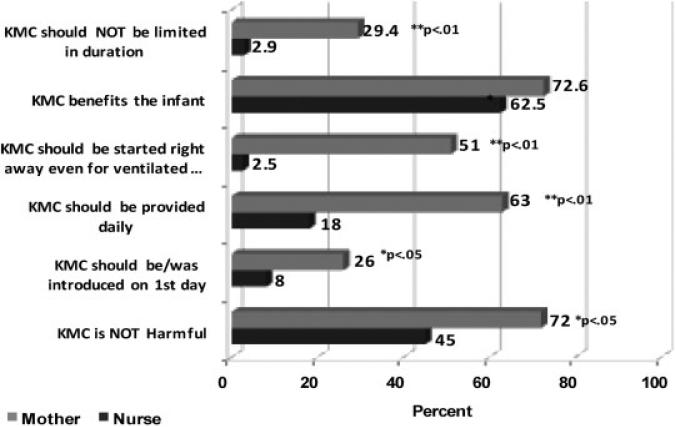

Perceptions of the Importance of KMC

The value placed on integration of KMC, a specific parental handling technique, was assessed between nurses and mothers in the NICU. Regardless of racial or ethnic background of nurses or mothers, there was no difference in the belief that KMC was a technique that benefited infants; both strongly identified this at 63% and 73%, respectively (p = 0.20, ▶Fig. 2). However, 51% of mothers compared with 2.5% of nurses felt that KMC should be started immediately after birth regardless of the infants’ ventilator status (p = 0.001), and 63% of mothers compared with 18% of nurses strongly believed that KMC should be provided daily to their infants (p = 0.001). Likewise, 26% of mothers strongly be lieved that KMC should be introduced during their infant's first day in the NICU compared with 8% of nurses (p = 0.018, ▶Fig. 2). Finally, 72% of mothers strongly believed that KMC was not harmful compared with 45% of nurses (p = 0.04), and 29% of mothers strongly believed that KMC should not be limited in duration compared with 2.9% of nurses (p = 0.004, ▶Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Nurses’ and mothers’ beliefs related to KMC in the NICU. Nurses and mothers strongly agreed in responses to survey questions on KMC. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Abbreviation: KMC, Kangaroo Mother Care.

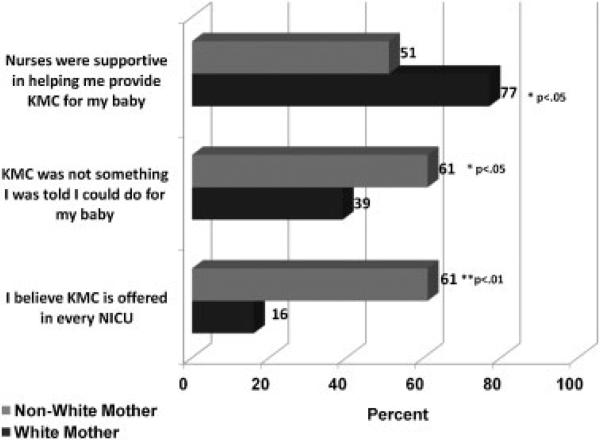

When perceptions of KMC were assessed by maternal race and ethnic background, 77% of white mothers compared with only 50% of nonwhite mothers strongly perceived that nurses were supportive in helping them provide KMC for their infant (p = 0.03, ▶Fig. 3). Overall almost half of mothers identified that KMC was not something they were told they could provide for their infant. Furthermore, 61% of nonwhite mothers compared with 39% of white mothers strongly identified that access to KMC had been limited to them and that KMC was not something that they were told they could provide for their baby (p = 0.002, ▶Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mothers’ beliefs of KMC provision based on racial and ethnic background. Mothers strongly agreed in responses to survey questions on KMC beliefs. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Abbreviations: KMC, Kangaroo Mother Care; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

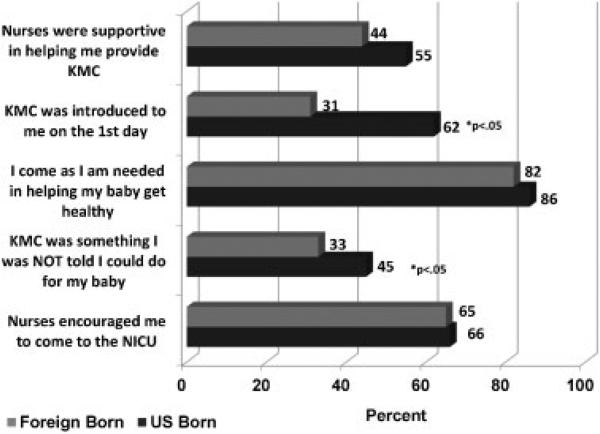

Finally, nonwhite mothers, foreign-born mothers, and white mothers did not differ in their strong perceptions that nurses made them feel welcome and included as part of the care team by nurses or for the reasons that they come to the NICU (▶Fig. 3 and ▶Fig. 4). However, foreign-born mothers perceived limited access to KMC and were less likely to have been introduced to KMC on the first day or to be told that KMC was something they could do for their baby compared with U.S.-born mothers (31% versus 62%, p = 0.042, ▶Fig. 4). Once KMC was established, foreign-born mothers perceived equal support by nurses in the provision of KMC, felt encouraged to come to the NICU, and perceived that they came to the NICU for the same reasons as their U.S.-born counterparts (▶Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Mothers’ beliefs of KMC and maternal care partnership based on maternal place of birth background. Mothers strongly agreed in responses to survey questions on KMC and care partnership beliefs. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Abbreviations: KMC, Kangaroo Mother Care; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

When perceptions of KMC were assessed by nurse's race, ethnicity, and place of birth, nonwhite and foreign-born nurses were more likely to strongly perceive that KMC was of value and offered in every NICU and to identify that they introduced KMC on the first day in the NICU (▶Table 2). Those nurses who had children regardless of race or ethnicity strongly believed that KMC should be started right after birth (▶Table 2).

Discussion

Cultural and linguistic differences and levels of acculturation can affect communication, level of trust, and the ability to navigate the American health system that is increasingly diverse.15–18 Additionally, culturally competent health care, provided in the context of each patient's cultural values, has the potential to improve the health of minorities by improving physician-patient communication and care delivery.15–17 As such, culturally competent education of providers has focused on providers understanding parents’ cultural characteristics, including ethnic and religious beliefs that might impact on provision of care.16 Nevertheless, individual providers have self-imposed culture-based perceptions and beliefs, many of which are unrecognized. The focus of this study was to assess concordance and barriers of neonatal nurse and maternal perceptions of the value of KMC as well as perceptions of family-centered characteristics through assessing views of maternal presence in the NICU for care partnership. KMC and maternal care provision have become an important aspect of care in the NICU associated with improved short-and long-term neonatal care health outcome.4–7 Our results identify discordant overall strength of belief between mothers and nurses as well as racial/ethnic and foreign-born cultural associations with strength of belief of KMC value and maternal involvement in care of the infant. As a group, neonatal nurse providers valued KMC but to a lesser degree than mothers. A particularly unexpected finding was the disparity between mothers’ and nurses’ views related to maternal presence in the NICU as only 21% of nurses strongly held this belief compared with 67% of mothers. Furthermore, nurses and mothers of nonwhite racial backgrounds and/or nurses with children placed a far greater value on maternal presence in the NICU as well as the use of KMC as a technique to improve infant health. Nonwhite nurses and nurses with children were also more likely to strongly agree that they encourage mothers to provide KMC early and for an unlimited duration of care. Of note, a greater proportion of nonwhite and foreign-born mothers identified that the technique of KMC was not accessible to them, that KMC was not something that they were made aware of by their nurse, or that this information was delayed in its presentation compared with U. S.-born or white mothers. Given the structure of teams in the NICU, the identification of differences in the value of KMC among nurse providers implies that based on nursing assignment, within a given NICU, mothers of infants with similar medical status may experience a variation in access to KMC or ability to partner in their child's care. This inconsistency in access to KMC based on nursing assignment was identified in maternal commentary during this study.

In adult populations, racial and ethnic concordance can enhance adult patient satisfaction.15,16,18–22 Given the increased diversity of mothers in the United States and limited diversity of nursing and physician providers, opportunities to address training and knowledge of individual maternal beliefs may be important to enhance the use of KMC and maternal care partnerships in the NICU. Our data demonstrated perceived variability in KMC use and access in mothers of different racial demographics and provided an opportunity to initiate guidelines that would assist neonatal nurse providers in the standardized use of KMC in each NICU. This study population was limited to mothers and nurses in a widely diverse urban area within a large urban hospital system whose population resided in the northeast. Furthermore, our nursing population reflected a group of racially diverse and foreign-born providers permitting assessment of provider perception based on cultural background. Thus, our results may not be reflective of other less diverse nursing or maternal cultural populations within the United States. Nevertheless, this opportunity provided evidence of specific disparities in maternal and nursing opinions that define important aspects of care access within the context of the NICU. Our findings are consistent with other qualitative studies of provider and diverse patient populations that identify perceived barriers to care access among racial and ethnically diverse patients or among patients and providers.15,23 Our study expands further to identify overall provider-parent care barriers related to access and utilization of an FCC technique, KMC, in mothers in those NICUs without provider guidelines for KMC implementation or care provision.

Our previous work underscored neonatal nurse barriers in key aspects of developmental care that involved parental partnerships.14,24 Several factors including perceived support of physician staff, support of other colleagues, as well as individual comfort level in providing training or education of parents of varied cultural backgrounds and education as well as attainment of parental proficiency were identified. This study further delineates discordance of mothers’ and nurses’ perceptions of KMC as well as maternal integration in infant care partnerships the NICU. These results provide avenues to explore the development of provider educational infant care guidelines in the NICU. Such NICU care plans or provider guidelines focused on provider KMC beliefs as well as value of parent care partnership will likely be important educational discussions for NICU providers to address perceived maternal barriers in the provision of high-quality NICU care with diverse patient populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nok Chhun, MS, the neonatal nurses, and the parents who participated in this survey. This work was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, grant number 1R21HD059047, and an educational research grant to K.D. Hendricks-Muñoz from the Jack Cary Eichenbaum Foundation.

References

- 1.Conde-Agudelo A, Belizán JM, Diaz-Rossello J. Kangaroo mother care to reduce morbidity and mortality in low birthweight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(3):CD002771. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawn JE, Mwansa-Kambafwile J, Horta BL, Barros FC, Cousens S. “Kangaroo mother care” to prevent neonatal deaths due to pre-term birth complications. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(Suppl 1):i144–i154. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD003519. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milette IH, Richard L, Martel MJ. Evaluation of a developmental care training programme for neonatal nurses. J Child Health Care. 2005;9:94–109. doi: 10.1177/1367493505051400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludington-Hoe SM, Swinth JY. Developmental aspects of kangaroo care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1996;25:691–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Alencar AE, Arraes LC, de Albuquerque EC, Alves JG. Effect of kangaroo mother care on postpartum depression. J Trop Pediatr. 2009;55:36–38. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmn083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin T. Family-centered care in the NICU. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2006;20:98–102. doi: 10.1097/00005237-200601000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones L, Woodhouse D, Rowe J. Effective nurse parent communication: a study of parents’ perceptions in the NICU environment. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reis MD, Scott SD, Rempel GR. Including parents in the evaluation of clinical microsystems in the neonatal intensive care unit. Adv Neonatal Care. 2009;9:174–179. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e3181afab3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lupton D, Fenwick J. “They’ve forgotten that I'm the mum”: constructing and practising motherhood in special care nurseries. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:1011–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00396-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chia P, Sellick K, Gan S. The attitudes and practices of neonatal nurses in the use of kangaroo care. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2006;23:20–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Theory-based behavior change interventions: comments on Hobbis and Sutton. J Health Psychol. 2005;10:27–31. doi: 10.1177/1359105305048552. discussion 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ring N, Malcolm C, Coull A, Murphy-Black T, Watterson A. Nursing best practice statements: an exploration of their implementation in clinical practice. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:1048–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hendricks-Muñoz KD, Louie M, Li Y, Chhun N, Prendergast CC, Ankola P. Factors that influence neonatal nursing perceptions of family-centered care and developmental care practices. Am J Perinatol. 2010;27:193–200. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1234039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Betancourt JR, Maina AW. The Institute of Medicine report “Unequal Treatment”: implications for academic health centers. Mt Sinai J Med. 2004;71:314–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O II. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:293–302. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):181–217. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, Denekens J. Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26:331–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strumpf EC. Racial/ethnic disparities in primary care: the role of physician-patient concordance. Med Care. 2011;49:496–503. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820fbee4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maddalena V. Cultural competence and holistic practice: implications for nursing education, practice, and research. Holist Nurs Pract. 2009;23:153–157. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0b013e3181a056a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:997–1004. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.9.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singleton K, Krause EM. Understanding cultural and linguistic barriers to health literacy. Ky Nurse. 2010;58:4, 6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorkin DH, Ngo-Metzger Q, De Alba I. Racial/ethnic discrimination in health care: impact on perceived quality of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:390–396. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1257-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendricks-Muñoz KD, Prendergast CC. Barriers to provision of developmental care in the neonatal intensive care unit: neonatal nursing perceptions. Am J Perinatol. 2007;24:71–77. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-958156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]