Abstract

The present study aimed to test the hypothesis that cues associated with drug-taking behavior become extra strong motivators of behavior compared to cues paired with non-drug reinforcers. In Experiment 1, rats were trained to lever press for intravenous cocaine infusions and grain pellets. Each reinforcer was paired with a distinct audiovisual cue. When allowed to choose between these alternatives, rats chose grain on ~70–80% of trials. However, after extinguishing lever pressing, reintroduction of press-contingent cues during a test for cue-induced reinstatement generated more cocaine seeking than grain seeking (also observed on 3- and 8-week follow up tests). To examine whether the same pattern of results would occur with two non-drug reinforcers, Experiment 2 replicated Experiment 1 using grain and sucrose as reinforcement alternatives. Rats chose sucrose over grain on ~70–80% of choice trials and also responded more for the sucrose cue than for the grain cue on the reinstatement test. The disconnect between primary and conditioned reinforcement in Experiment 1 but not Experiment 2, suggests that drug cues may become exceptionally strong motivators of drug-seeking. These results are consistent with cue-focused theories of addiction and may offer insight into the persistent cue-driven drug-seeking behavior observed in addiction.

Keywords: Choice, Cocaine, Cue-induced Reinstatement, Food, Rat, Self-administration

A growing number of laboratory studies have shown that, in rats, cocaine is not an especially powerful reinforcer compared to non-drug reinforcers like food. For example, if given a choice between a cocaine infusion and a food pellet (or a drop of sweet liquid), rats generally prefer the food/liquid option (Cantin et al. 2010; Kerstetter et al. 2012; Lenoir et al. 2007; for reviews see Ahmed 2010, 2012). This preference for the non-drug alternative has been observed across a range of cocaine doses (Cantin et al. 2010), and appears to be largely independent of the nutritive value of the food alternative (Lenoir et al. 2007), the extent of past cocaine use in the animal, or the level of food or water deprivation (Cantin et al. 2010; Kerstetter et al. 2012). It is clear that animals are sensitive to the cost of both drug and non-drug reinforcement, as it is possible to shift preference in favor of the drug alternative by increasing the cost of the food alternative (Cantin et al. 2010; Thomsen et al. 2013). However, behavioral economic studies comparing the essential values of cocaine and food in rats (i.e., their willingness to defend consumption of each over a range of prices) have found that cocaine is a weak reinforcer compared to food (Christensen et al. 2008a, 2008b). These rat studies are consistent with findings that human cocaine users presented with a choice between cocaine and a small non-drug reward (e.g., $1–2 or tokens that could be traded for snacks) often chose the non-drug alternative (e.g. Foltin & Fischman 1994; Higgins, Roll & Bickel 1996; for review, see Higgins, Heil & Lussier 2004). These results suggest that primary reinforcing strength alone cannot explain the ability of drugs like cocaine to cause addiction.

This raises the question: if cocaine is not such a powerful reward, then what is responsible for the excessive drug-seeking behavior that characterizes addiction? One possibility is that drug-paired cues—e.g., people, places, or things associated with the drug-taking experience—gain more control over behavior than would be expected given their primary reinforcing strength. Exposure to such a strong motivator of drug-seeking behavior would then place an abstinent drug abuser at a high risk for relapse, making it difficult for the individual to permanently cease drug-taking behavior (Sinha & Li 2007; Kosten et al. 2005). Several prominent theories of drug addiction (e.g., Robinson & Berridge 1993, 1998; Di Chiara 1999; Redish 2004) posit that abused drugs affect the dopamine system in ways that produce conditioned cues that are unusually strong as compared to cues paired with non-drug rewards. These powerful drug cues, according to these theories, motivate the excessive drug-seeking behavior seen in addiction. Thus, even if cocaine acts as a weaker primary reinforcer than food, cocaine seeking may prevail over food seeking because cocaine cues are stronger motivators of behavior than food cues. The present study investigated this possibility.

In Experiment 1, rats were trained on a two-lever procedure to choose between cocaine and a grain pellet under conditions known to produce preference for grain. Each presentation of cocaine or grain was paired with a distinctive audiovisual cue. Then, to measure the relative power of these cues alone, a cue-induced reinstatement test (widely used to model human drug relapse; Epstein et al. 2006) was administered after lever pressing had been extinguished. In this test, lever pressing produced the cues previously associated with grain or cocaine, but not the primary reinforcers themselves. If the conditioned reinforcing properties of cues associated with cocaine and grain parallel the primary reinforcing properties of cocaine and grain, then greater cue-induced reinstatement of grain seeking would be expected. If, however, a cue paired with cocaine becomes a relatively stronger conditioned reinforcer than a cue paired with grain, greater cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking might occur.

Experiment 2 followed the same basic strategy as Experiment 1, but with two different types of food reinforcers (sucrose pellets vs. grain pellets) in place of cocaine and grain. It was expected that with two food reinforcers, the relative strength of conditioned reinforcing effects would parallel the difference in primary reinforcing effects. That is, the cue associated with the preferred food was expected to produce greater cue-induced reinstatement than the cue associated with the non-preferred food. Finding that the preferred primary reinforcer produced the stronger conditioned reinforcer in Experiment 2 (where two food reinforcers were compared), but the opposite pattern in Experiment 1, would suggest that cocaine produces unusually strong conditioned cues. Such a result could provide insight into drug addiction by helping explain what drives the compulsive seeking of a relatively weak reinforcer.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Twenty adult male Long-Evans rats completed Experiment 1. Nineteen adult male Long-Evans rats completed Experiment 2. Rats were individually housed in plastic cages with wood-chip bedding and metal wire tops. They were maintained at 85% of their free-feeding weights (approximately 300–400 g) throughout each experiment by feeding them approximately 15–20 g of rat chow following training sessions. Rats had unlimited access to water in their home cages. The colony room where the rats were housed had a 12-h light:dark cycle with lights on at 08:00 h. Training sessions in phases 1–3 of each experiment were conducted once per day, 5–7 days per week during the light phase of the light:dark cycle. Throughout the experiment, rats were treated in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy of Sciences 2011) and all procedures were approved by American University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Apparatus

Training in both experiments took place in 10 Med-Associates (St. Albans, VT) or Coulbourn Instruments (Whitehall Township, PA) modular test chambers (30.5 x 24 x 29 cm and 30 X 25.5 X 29 cm, respectively) enclosed in sound attenuation chests. Each chamber had aluminum front and rear walls, with a grid floor and two clear plexiglass side walls. Two Med-Associates retractable levers were positioned 5 cm from the floor and located on the front wall of the chamber, equidistant from the center where a food trough was located. Tone (4000 Hz and 70 dB) and white noise (65 dB) stimuli were delivered through a speaker mounted on top of the chamber. A shielded 100-mA houselight mounted to the ceiling at the front of the chamber was used to signal the start and end of sessions. Two 100-mA cue lights were also mounted to the front wall, located approximately 10 cm above the floor and directly above each lever. Experimental events were controlled by a Med-Associates computer system located in an adjacent room.

In Experiment 1, cocaine (National Institute on Drug Abuse) in a saline solution at a concentration of 2.56 mg/ml was infused at a rate of 3.19 ml/min by 10-ml syringes driven by Med-Associates syringe pumps located outside of the sound attenuation chests. Tygon tubing extended from the 10-ml syringes to a 22-gauge rodent single-channel fluid swivel and tether apparatus (Alice King Chatham Medical Arts, Hawthorne, CA) that descended through the ceiling of the chamber. Cocaine was delivered to the subject through Tygon tubing that passed through the metal spring of the tether apparatus. This metal spring was attached to a plastic screw cemented to the rat’s head to reduce tension on the catheter.

Surgery

Rats in Experiment 1 were surgically prepared with chronic indwelling jugular vein catheters, using a modification of the procedure originally developed by Weeks (1962) and described in detail elsewhere (Tunstall & Kearns 2013). Rats were given 5–7 days to recovery from surgery. Catheters were flushed daily with 0.1 ml of a saline solution containing 1.25 μg/ml heparin and 0.08 mg/ml gentamycin.

Procedure

Experiment 1

Phase 1: Operant Response Acquisition and Cue Conditioning

For half of the rats, the left lever was the cocaine lever and the right lever was the grain lever. For the other half, this arrangement was reversed. The start of each session was signaled by illumination of the houselight and lever insertion. In this phase, only one lever was inserted into the chamber per session, with the order of lever training counterbalanced across animals (i.e., cocaine or grain lever first). A response on the grain lever was reinforced with a grain pellet (45-mg dustless precision grain pellet, Bio-serv, New Brunswick, NJ) and a response on the cocaine lever was reinforced with a 1.0 mg/kg cocaine infusion. The selected cocaine dose was based on a previous study from this lab (Tunstall & Kearns 2013). Delivery of each reinforcer coincided with the presentation of a 10-s audiovisual stimulus consisting of illumination of the cue light above the lever and a tone or white noise auditory stimulus. The association of tone with grain and white noise with cocaine, or vice-versa, was counterbalanced over subjects. Lever presses during the 10-s cue were recorded, but had no consequences. During this phase, rats could earn up to 50 reinforcers in a session. If rats did not reach this criterion, the session was terminated after 2 hours if it was a grain training session or 3 hours if it was a cocaine training session. Rats continued training on this procedure with their designated lever and reinforcer until they earned a cumulative total of at least 150 reinforcers. Once they reached this criterion, they received training sessions (beginning on the next training day) with the other lever and other reinforcer until they earned at least 150 deliveries of that reinforcer. Thus, all rats had an approximately equal number of pairings of each reinforcer with its audiovisual cue prior to advancing to the next phase.

Phase 2: Choice Between Cocaine and Grain

During this phase, rats could choose to respond on either the cocaine lever or the grain lever. Following an established procedure (Tunstall & Kearns 2013; see also Lenoir et al. 2007; Cantin et al. 2010), each choice session began with four forced-choice trials, in which either the right or left lever was inserted. There were two trials of each type, with the order of presentation randomized within blocks of two. This ensured that rats sampled each response-outcome contingency twice at the beginning of each choice session. A lever press would result in delivery of the designated reinforcer (i.e., a cocaine infusion or a grain pellet), a 10-s presentation of the audiovisual cue associated with that reinforcer, and retraction of the lever. Each trial was followed by a 10-min intertrial interval (ITI). Following the completion of the forced-choice trials, there were 14 free-choice trials. Each free-choice trial began with the simultaneous insertion of both levers. A lever press on either lever resulted in the delivery of the designated reinforcer, 10-s presentation of the associated cue, and the immediate retraction of both levers. A 10-min ITI followed each free-choice trial. This relatively long ITI length was chosen to minimize the potential influence of accumulating cocaine doses on choice behavior (Cantin et al. 2010; Perry, Westenbroek & Becker 2013). In total, choice sessions lasted approximately 3 h and there were 5 such sessions.

Phase 3: Extinction

During this phase, both levers were inserted at the beginning of each 2-h extinction session and remained available to the animal for the entire session. Lever presses were recorded, but had no consequences (i.e., no grain, cocaine, or associated cues were presented). Extinction sessions continued until the rat either 1) made 15 or fewer responses on each lever in the same session, or 2) had at least 12 extinction sessions, and, on the final session, made fewer than 50 responses on each lever with the numbers of responses made on the two levers differing by less than 30.

Phase 4: Cue-induced Reinstatement Testing

On the day after meeting the extinction criterion, each rat received a cue-induced reinstatement test. The test began with a 100-s period during which both levers were retracted and rats were exposed to two non-contingent presentations of each 10-s audiovisual cue. The cocaine cue and grain cue alternated, with half of the subjects experiencing the cocaine cue first and the other half experiencing the grain cue first. A 10-s period separated each cue presentation. Following this brief non-contingent cue presentation period, the test began with illumination of the houselight and insertion of both levers into the chamber. Responding on either lever resulted in presentation of the appropriate audiovisual cue for 10 s. Responses during the cue were recorded, but had no consequences. The levers remained available to the rats for the duration of the 2-hr test.

A second and third reinstatement test was administered to each rat after approximately 3 weeks (20 – 27 days) and 8 weeks (56 – 62 days), respectively. These tests were administered to assess the persistence of potential cue-reinstating effects. These tests were the same as described above (including non-contingent cue presentations), except each test was preceded by a 15-min extinction period during which both levers were inserted, but lever pressing had no consequences. This pre-test extinction period was designed to temper any initial burst in lever pressing occurring as a result of spontaneous recovery (i.e., not cue-induced) which may have obfuscated cue-reinstating effects.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 used the same procedures as described above except, instead of cocaine vs. grain, the two reinforcers were different foods. One alternative was the delivery of 3, banana-flavored sucrose pellets (45-mg dustless precision sucrose pellet, Bio-serv, New Brunswick, NJ) and the other was a single grain pellet (See Experiment 1, Phase 1). The different amounts of food pellets were necessary to establish a preference (~70–80% choice of the preferred option) that was comparable in strength to that observed in Experiment 1. Also, during the choice phase, the length of the ITI was 200 s rather than 10 min, since cumulative dosing effects were not a potential concern. All other aspects of the procedure were the same as described in Experiment 1 above.

Statistical Analyses

For all statistical tests, significance was set at α = 0.05. Baseline preference was analyzed using a one-sample t-test to compare percentage of cocaine choices made during the final two choice sessions to a test value of 50% (i.e., the expected percentage observed with indifferent choice behavior). The total number of responses on each lever was the measure used for analysis in the extinction and reinstatement phases. Repeated measures ANOVAs, with lever and session as within-subjects variables, were performed on the data from the extinction and reinstatement phases. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to assess the relationship of lever preference (percentage of total responses on a lever) observed in the choice phase and in the extinction phase with that displayed during each reinstatement test.

Results

Experiment 1

Phase 1: Operant Response Acquisition and Cue Conditioning

Rats in Experiment 1 required a mean of 4.1 (SEM = 0.4) sessions to meet the grain lever-pressing criterion and the mean total number of grain pellets earned, and pairings of grain with its cue, was 156.5 (SEM = 2.7). A mean of 10.2 (SEM = 0.8) sessions were required to meet the cocaine lever-pressing criterion and the mean total number of cocaine infusions earned, and pairings of cocaine with its cue, was 164.3 (SEM = 2.5).

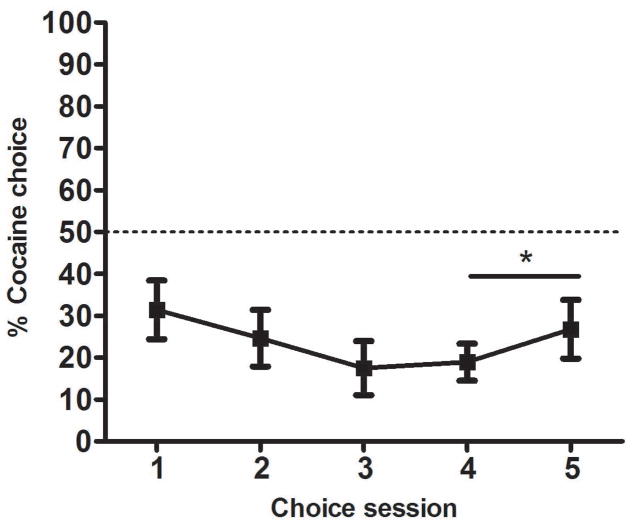

Phase 2: Cocaine vs. Grain Choice

Fig. 1 shows that rats chose cocaine over grain on approximately 20–30% of trials. In general, rats’ preferences were stable by the end of the choice phase, with a mean change in choice percentage of 15% across the final two sessions. Only one rat demonstrated a large shift in preference on the last two choice sessions and was thus given an extra choice session to allow preference to stabilize. A one-sample t-test confirmed that the percentage of choices for cocaine averaged over the final two sessions was significantly less than 50% (t (19) = −5.0, p <.001), the percentage representing non-preference. Due to the preference for grain responding during this phase, rats finished their reinforced lever-press training with a greater total number of grain reinforcements (M = 220.6, SEM = 3.9) than cocaine reinforcements (M = 191.1, SEM = 4.2).

Figure 1. Choice between cocaine and grain in Experiment 1.

Mean percentage (±SEM) of free-choice trials (14 per session) on which cocaine was chosen, across the 5 sessions of the choice phase. * p < 0.001 different from 50% (i.e. no preference).

Phase 3: Extinction

Rats required a mean of 10.4 sessions (SEM = 0.4) to reach the extinction criterion. As the fewest sessions required for a rat to meet the extinction criterion was 5 sessions, responding on the first 2 and last 3 extinction sessions is shown for all rats in Fig. 2. Rats responded slightly more on the grain lever than the cocaine lever at the start of extinction, but by the final session mean responding decreased to less than 20 responses on each lever. These observations were confirmed by a 2 X 5 (lever by session) repeated measures ANOVA performed on those sessions shown in Fig. 2. There was a significant main effect of session (F[4,76] = 156.6, p < 0.001) and a significant session-by-lever interaction (F[4,76] = 5.8, p < 0.001) but no main effect of lever (F[1,76] = 0.6, p = 0.46).

Figure 2. Extinction of cocaine- and grain-maintained responding in Experiment 1.

Mean total responses (±SEM) recorded on the grain and cocaine levers during the first two and last 3 extinction sessions. Responding on either lever did not result in reinforcement or presentation of the 10-s audio-visual timeout cues previously paired with each lever.

Phase 4: Cue-induced Reinstatement Testing

Fig. 3 presents results from the cue-induced reinstatement tests. Each bar represents total test responses, with the line across the bars indicating the number of responses resulting in cue presentation (below the line) and the number of responses during the cue itself (above the line). Data from the final extinction session is also presented for comparison. Re-introduction of the cues previously associated with cocaine or grain increased responding on both levers (“Next day” test vs. final extinction session). This reinstatement was greater on the cocaine lever than on the grain lever. From rates observed on the final extinction session, total response rates approximately doubled on the grain lever and approximately tripled on the cocaine lever.

Figure 3. Cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine and grain seeking in Experiment 1.

Mean total responses (±SEM) on the cocaine and grain levers during the last day of extinction (Last ext. session) and on the 2-h cue-induced reinstatement tests, administered the next day and after 3 and 8 weeks. The line through each bar is used to show the composition of total test responses. Responses below the line were those that initiated the 10-s cue, while those above were made during the 10-s cue presentation.

A 2 X 2 (lever by session) repeated measures ANOVA performed on total responses from the final extinction session and first test session confirmed that reinstatement occurred and that reinstatement of cocaine seeking was greater than reinstatement of grain seeking. There was a significant main effect of session (F[1,19] = 58.1, p < 0.001), and of lever (F(1,19) = 11.7, p < 0.005), and a significant session-by-lever interaction F(1,19) = 9.9, p = 0.005).

The tendency to respond more on the cocaine lever than on the grain lever was maintained across the 3- and 8-week follow-up reinstatement tests. While responding generally decreased over tests, the mean percentage of total test responses made on the cocaine lever was 59%, 61% and 62% across the 3 reinstatement tests. A 2 X 3 (lever by session) repeated measures ANOVA performed across the 3 reinstatement tests revealed a significant main effect of lever (F[1,17] = 8.4, p = 0.01) and session (F[2, 34] = 6.7, p < 0.005), but no significant lever-by-session interaction (F[2,34] = 2.2, p = 0.125). Due to health complications, not all rats could complete all follow-up reinstatement tests. One rat dropped out prior to the 3-week test and one additional rat dropped out prior to the 8-week test.

Correlations of Lever Preference in Choice and in Extinction with Reinstatement Testing

The left panels of Fig. 4 present individual subjects’ percentages of total test responses made on the cocaine lever during each reinstatement test plotted as a function of percent of choices for cocaine during the final two choice phase sessions. These scatterplots show that a subject’s preference for primary reinforcement when both alternatives were available was not predictive of the distribution of responses between levers on the reinstatement tests (all Pearson rs < 0.3, ps > 0.2).

Figure 4. Correlation of lever preference in choice and in extinction with lever preference in each reinstatement test in Experiment 1.

Individual subjects’ percentages of responses made on the cocaine lever during each reinstatement test plotted as a function of their percentage of cocaine choices during the final two choice phase sessions (left panels) and the percentage of extinction responses they made on the cocaine lever (right panels). Linear regression was used to plot the line of best fit shown in each graph.

In contrast, the distribution of responses between levers during extinction was strongly associated with the distribution of responses on the reinstatement tests. The right panels of Fig. 4 present individual subjects’ percentages of responses made on the cocaine lever during each reinstatement test plotted as a function of percentage of total responses made on the cocaine lever across the whole extinction phase. Subjects who responded more on the cocaine lever during extinction also tended to respond more on the cocaine lever during the next-day reinstatement test (r[18] = 0.772, p < 0.001), 3-week test (r[17] = 0.655, p = 0.002), and 8-week test (r[16] = 0.548, p = 0.018).

Experiment 2

Phase 1: Operant Response Acquisition and Cue Conditioning

In Experiment 2, rats required a mean of 3.4 (SEM = 0.1) and 3.7 (SEM = 0.3) sessions to meet the acquisition criterion on the grain and sucrose levers, respectively. Across these sessions, subjects earned mean totals of 155.1 (SEM = 2.7) and 163.2 (SEM = 4.2) reinforcers, and cue pairings, on the grain and sucrose levers, respectively.

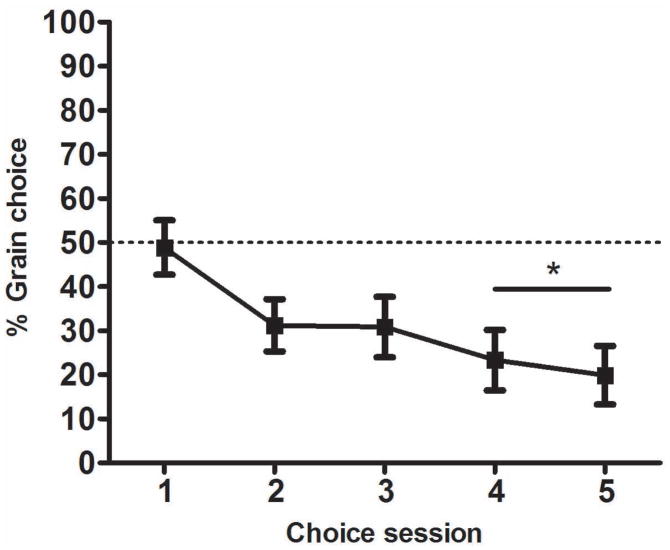

Phase 2: Grain vs. Sucrose Choice

Fig. 5 shows percent choice of the grain lever across the 5 choice sessions. Rats generally preferred sucrose over grain. By the end of this phase, rats chose grain on only 20–30% of trials, approximately the frequency with which they chose cocaine in Experiment 1. The mean change in choice percentage over the final two sessions was 6.4% (SEM = 2.0). A one-sample t-test performed on the average choice percentage from these two sessions indicated that rats’ preference for grain was significantly less than 50%, the percentage reflecting indifference (t(18) = 4.3, p < 0.001). Due to this preference for the sucrose alternative, by the end of this phase rats had a greater total number of reinforcements with the sucrose alternative (M = 221.6, SEM = 6.1) than the grain alternative (M =186.6, SEM = 4.8).

Figure 5. Choice between sucrose and grain in Experiment 2.

Mean percentage (±SEM) of free-choice trials (14 per session) on which grain was chosen, across the 5 sessions of the choice phase. * p < 0.001 different from 50% (i.e. no preference).

Phase 3: Extinction

Rats required 6 sessions on average (SEM = 0.4) to reach the extinction criterion. As the fewest sessions required for a rat to meet the extinction criterion was 4 sessions for any rat, responding on the first 2 and last 2 extinction sessions is shown for all rats in Fig. 6. Rats initially responded more on the lever associated with the preferred reinforcer (i.e., sucrose), as was the case in Experiment 1. By the end of extinction, rats made on average fewer than 10 responses per session on either lever. A 2 X 4 (lever by session) repeated measures ANOVA confirmed that there was a significant main effect of session (F[3,54] = 69.1, p < 0.001), lever (F[1,54] = 11.0, p < 0.005), and a significant session-by-lever interaction (F[3,54] = 6.1, p = 0.001).

Figure 6. Extinction of sucrose- and grain-maintained responding in Experiment 2.

Mean total responses (±SEM) recorded on the sucrose and grain levers during the first two and last two extinction sessions. Responding on either lever did not result in reinforcement or presentation of the 10-s audio-visual timeout cues previously paired with each lever.

Phase 4: Cue-induced Reinstatement Testing

Fig. 7 presents results from the reinstatement tests. Re-introduction of the cues previously associated with reinforcement produced an increase in responding on both levers (i.e., reinstatement of both sucrose- and grain-seeking), but, in contrast to Experiment 1, greater reinstatement was observed on the lever associated with the reinforcer that was preferred during the earlier choice phase (i.e., the sucrose lever). A 2 X 2 (lever by session) repeated measures ANOVA performed on total responses confirmed that there were significant main effects of lever (F[1,18] = 4.9, p < .05) and session (F[1, 18] = 19.2, p < 0.001), but no significant interaction (F[1, 18] = 3.8, p = 0.066).

Figure 7. Cue-induced reinstatement of sucrose and grain seeking in Experiment 2.

Mean total responses (±SEM) recorded on the sucrose and grain levers during the last day of extinction (Last ext. session) and on the 2-h cue-induced reinstatement tests, administered the next day and after 4 and 8 weeks. The line through each bar is used to show the composition of total test responses. Responses below the line were those that initiated the 10-s cue, while those above were made during the 10-s cue presentation.

In Experiment 2, the higher responding on the sucrose lever compared to the grain lever persisted at least through the 3-week test. The average percent sucrose lever responding on the next-day, 3-week, and 8-week tests was 64%, 68% and 58%, respectively. Responding generally decreased over tests and it appears that the strength of the sucrose-lever preference also weakened with repeated testing. These observations were confirmed by a 2 X 3 (lever by session) repeated measures ANOVA performed on total test responses which indicated a significant main effect of lever (F[1,18] = 4.7, p < 0.05) and session (F[2, 36] = p < 0.005) as well as a significant lever by session interaction (F[2, 36] = 3.4, p < 0.05).

Correlations of Lever Preference in Choice and in Extinction with Reinstatement Testing

The left panels of Fig. 8 present for individual subjects the percent sucrose lever responding on each of the 3 reinstatement tests plotted as a function of percent choices for sucrose during the final two sessions of the choice phase. As in Experiment 1, there was no significant correlation between these measures on any test (all Pearson rs between −0.02 and 0.35, all ps > 0.14). The right panels of Fig. 8 present percent responding on the sucrose lever during each reinstatement test plotted as a function of the percent responding on the sucrose lever over the whole extinction phase. Now, there were significant correlations on each test (all rs 0.74, all ps < 0.001), as was the case in Experiment 1. The distribution of responses over levers during extinction was predictive of how individuals responded on the reinstatement tests.

Figure 8. Correlation of Lever Preference in Choice and in Extinction with Lever Preference in each Reinstatement Test in Experiment 2.

Individual subjects’ percentages of responses made on the sucrose lever during each reinstatement test plotted as a function of their percentage of cocaine choices during the final two choice phase sessions (left panels)–and the percentage of extinction responses they made on the cocaine lever (right panels). Linear regression was used to plot the line of best fit shown for each graph.

Discussion

Rats in Experiment 1 preferred grain over cocaine (~70–80% of choices), replicating previous findings from this lab (e.g., Tunstall & Kearns 2013). However, following lever-press extinction, a cocaine cue produced greater reinstatement than did a grain cue. In Experiment 2, rats preferred the 3-pellet sucrose alternative to a grain pellet (~70–80% of choices) and following lever-press extinction, the sucrose cue produced greater reinstatement than did the grain cue. Thus, in Experiment 2 the relative strength of the conditioned reinforcers paralleled the relative strength of the primary reinforcers used to generate them. In contrast, in Experiment 1 the weaker primary reinforcer (i.e., cocaine) produced the stronger conditioned reinforcer and more effective reinstater. These findings suggest that drugs generate relatively potent conditioned cues, which are motivators of behavior in their own right. This may help explain why drug cues are so effective in triggering relapse (Sinha & Li 2007; Kosten et al. 2005).

The results of this experiment are consistent with previous studies suggesting that, in general, cues associated with drug reinforcement may be stronger than cues paired with non-drug reinforcement (see for review, Kearns, Gomez-Serrano & Tunstall, 2011). For example, Ciccocioppo, Martin-Fardon & Weiss (2004) performed an experiment comparing discriminative stimuli (SDs) that signaled cocaine or sweetened condensed milk availability. Separate groups of rats experienced only a single session in which a white-noise SD set the occasion for cocaine- or milk-reinforced lever pressing. They found that the cocaine SD exerted stronger and more persistent control over lever pressing than the milk SD. Similar differences between cocaine cues and sucrose cues have been noted in the incubation of craving paradigm (Lu et al., 2004).

The results of the present study fit well with Robinson & Berridge’s (1993, 1998, 2008) incentive-salience theory of addiction. According to this theory, the primary role of dopamine is not in reinforcement learning or in mediating the hedonic aspects of reinforcement, but in the attribution of incentive-salience to reward-associated cues (Berridge 2007; Robinson et al. 2005; Wise 2004). When previously neutral stimuli are paired with rewards, they are converted into “motivational magnets” that attract the organism and can serve as reinforcers in their own right. Dopamine modulates the attribution of incentive salience to the reward-paired cues. The exaggerated dopamine response produced by drugs like cocaine causes the cues associated with them to become especially strong motivational magnets as compared to cues associated with non-drug rewards. Excessive attribution of incentive salience to the cocaine cue could explain why it acted as a stronger conditioned reinforcer than the grain cue in Experiment 1.

The results of Experiment 1 are also consistent with Robinson & Berridge’s hypothesis that the hedonic properties of a reinforcer (“liking”) are dissociable from its ability to generate incentive-motivation (“wanting”; Berridge 2012; Robinson & Berridge 2013; Tindell et al. 2009). Rats in Experiment 1 chose grain over cocaine when both alternatives were available, suggesting that cocaine had relatively weaker hedonic properties (i.e., was “liked” less) than grain. But the cocaine cue – which, according to the theory would have been imbued with more incentive salience – generated a greater amount of seeking (or “wanting”) behavior than did the grain cue.

The correlational analyses performed across experiment phases further supports the hypothesis that hedonic (“liking”) and incentive-motivational (“wanting”) aspects of reinforcement are dissociable. The analyses revealed that for Experiment 1 (Fig. 4, left side) and Experiment 2 (Fig. 8, left side), there was no evidence of a relationship between rats’ primary reinforcer preference (“liking”) and their pattern of reinforcer seeking (“wanting”) in any of the tests of cue-induced reinstatement (for similar result, compare whole-test cue-induced reinstatement in male “cocaine-preferring” and “pellet-preferring” rats; Fig 6. a., Perry, Westenbroeck & Becker 2013). However, when lever preference across extinction was calculated for rats in each experiment, it became clear that in both Experiment 1 (Fig. 4, right side) and Experiment 2 (Fig. 8, right side) there was a strong, positive correlation between the reinforcer-seeking behavior displayed across the extinction phase and on the next-day, 3 week and 8 week reinstatement tests. This pattern of results suggests that, despite being unrelated to their primary reinforcer preferences, rats’ reinforcer-seeking behavior (“wanting”) in the absence of reinforcement was consistent across the extinction and cue-induced reinstatement phases of the experiment.

The results of the present study are also consistent with theories of addiction positing that abused drugs, through their effects on the mesolimbic dopamine system, produce an over-learning, or extra “stamping in”, of cue-reinforcer associations (DiChiara 1999; Redish 2004). It has been well established that phasic dopamine release in the striatum drives the learning of cue-reward associations (Schultz 1999, 2002; Steinberg et al. 2013; Waelti, Dickinson & Schultz 2001). Early in learning, reinforcer delivery is an unexpected outcome that produces a phasic dopamine response. With non-drug reinforcers like fruit juice, the dopamine response to reinforcer delivery diminishes or disappears as the subject learns the cue-reinforcer delivery and comes to expect the reinforcer when the cue is presented (Waelti et al. 2001). With no phasic dopamine response, no further learning takes place (i.e., learning is at asymptote). DiChiara (1999) and Redish (2004) hypothesized that a critical difference between drug and non-drug reinforcers is that the phasic dopamine response to drug reinforcers never diminishes due to their direct neuropharmacological actions (e.g., dopamine reuptake blockade). This perpetual dopamine surge produced by drugs, but not non-drug rewards, is believed to produce an over-strengthening of cue-drug associations, resulting in unusually strong conditioned drug cues. While the results of the present study are consistent with this idea, previous studies designed to test the over-learning hypothesis have not found support for it (e.g., Marks et al. 2010; Panlilio, Thorndike & Schindler 2007).

In interpreting the result of Experiment 1, differences between the grain and cocaine consummatory response may be important. With grain, there was a separate consummatory response (collect, chew, swallow) that followed the instrumental lever press. With cocaine, the lever press may have served as both the instrumental and consummatory response (Wise, 1987). This difference may be relevant to the outcome of Experiment 1 because a previous study (Delamater, 1997) of priming-induced reinstatement found more selective reinstatement of consummatory responses than for instrumental responses. It should be noted, however, that priming-induced and cue-induced reinstatement occur via distinct mechanisms, both neurobiological (e.g., Fuchs et al., 2004) and behavioral. Cue-induced reinstatement is a test of conditioned reinforcement, as rats’ lever pressing results in cue presentation (Yager & Robinson, 2013) and reinstatement depends on the cues being presented response contingently (Grimm et al., 2000). In contrast, in priming-induced reinstatement, the priming event only occurs prior to the test. Future research is needed to determine if cue-induced reinstatement is influenced by response type (instrumental vs. consummatory). Our goal here was to equate the physical response – i.e., a lever press – necessary to turn on the cues previously associated with both cocaine and food so that we could directly compare these cues.

In summary, the results of the present study support the notion that drug cues can become inordinately strong motivators of behavior, and can contribute to situations in which drug-seeking can prevail over the seeking of non-drug reinforcers. This was especially remarkable in the present study because it was demonstrated under conditions where cocaine was a weaker primary reinforcer than the food alternative. Conditioned cues associated with drug reinforcement may offer an explanation for how a drug which is not a strong primary reinforcer can motivate the persistent drug seeking observed in addiction. This highlights the importance of pre-clinical research aimed at developing interventions to specifically target drug cues. A successful intervention would likely have great utility in treating the persistent and recurrent drug seeking observed in human drug addicts.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number R01DA008651 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse as well as a Doctoral Dissertation grant from the Society for the Advancement of Behavior Analysis awarded to BT. The National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Society for the Advancement of Behavior Analysis had no role other than financial support and as such the content is solely the responsibility of the authors.

Footnotes

Authors contribution

BT and DK were responsible for the study concept and design. BT acquired and analyzed data. DK assisted with data analysis and interpretation of findings. BT drafted the manuscript. DK provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Both authors critically reviewed content and approved final version for publication.

References

- Ahmed SH. Validation crisis in animal models of drug addiction: Beyond non-disordered drug use toward drug addiction. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH. The science of making drug addicted animals. Neuroscience. 2012;211:107–125. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC. The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:391–431. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC. From prediction error to incentive salience: mesolimbic computation of reward motivation. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35:1124–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.07990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantin L, Lenoir M, Augier E, Vanhille N, Dubreucq S, Serre F, Vouillac C, Ahmed SH. Cocaine Is Low on the Value Ladder of Rats: Possible Evidence for Resilience to Addiction. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(7):e11592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen CJ, Silberberg A, Hursh SR, Huntsberry ME, Riley AL. Essential value of cocaine and food in rats: tests of the exponential model of demand. Psychopharmacology. 2008a;198:221–229. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen CJ, Silberberg A, Hursh SR, Roma PG, Riley AL. Demand for cocaine and food over time. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008b;91:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Stimuli associated with a single cocaine experience elicit long-lasting cocaine-seeking. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:495–496. doi: 10.1038/nn1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamater AR. Selective reinstatement of stimulus-outcome associations. Anim Learn Behav. 1997;25:400–412. [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G. Drug addiction as dopamine-dependent associative learning disorder. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;375:13–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Preston KL, Stewart J, Shaham Y. Toward a model of drug relapse: an assessment of the validity of the reinstatement procedure. Psychopharmacology. 2006;189:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Effects of buprenorphine on the self-administration of cocaine by humans. Behav Pharmacol. 1994;5:79–89. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199402000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Evans KA, Parker MP, See RE. Differential involvement of orbitofrontal cortex subregions in conditioned cue-induced and cocaine-primed reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6600–6610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1924-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, Kruzich PJ, See RE. Contingent access to stimuli associated with cocaine self-administration is required for reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. Psychobiology. 2000;28:383–386. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Roll JM, Bickel WK. Alcohol pretreatment increases preference for cocaine over monetary reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 1996;123:1–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02246274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Lussier JP. Clinical implications of reinforcement as a determinant of substance use disorders. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:431–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns DN, Gomez-Serrano MA, Tunstall BJ. A review of preclinical research demonstrating that drug and non-drug reinforcers differentially affect behavior. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4:261–269. doi: 10.2174/1874473711104040261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter KA, Ballis MA, Duffin-Lutgen S, Carr AE, Behrens AM, Kippin TE. Sex differences in selecting between food and cocaine reinforcement are mediated by estrogen. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;37:2605–2614. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Scanley BE, Tucker KA, Oliveto A, Prince C, Sinha R, Potenza MN, Skudlarski P, Wexler BE. Cue-induced brain activity changes and relapse in cocaine-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;31:644–650. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir M, Serre F, Cantin L, Ahmed SH. Intense Sweetness Surpasses Cocaine Reward. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(8):e698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Grimm JW, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal: a review of preclinical data. Neuropharmacol. 2004;47:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks KR, Kearns DN, Christensen CJ, Silberberg A, Weiss SJ. Learning that a cocaine reward is smaller than expected: a test of Redish’s computational model of addiction. Behav Brain Res. 2010;212:204–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Sciences. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Thorndike EB, Schindler CW. Blocking of conditioning to a cocaine-paired stimulus: testing the hypothesis that cocaine perpetually produces a signal of larger-than-expected reward. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:774–777. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry AN, Westenbroek C, Becker JB. The development of a preference for cocaine over food identifies individual rats with addiction-like behaviors. PloS ONE. 2013;8(11):e79465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redish AD, Jensen S, Johnson A. A unified framework for addiction: vulnerabilities in the decision process. Behav Brain Sci. 2008;31:415–437. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0800472X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redish AD. Addiction as a computational process gone awry. Science. 2004;306:1944–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.1102384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res. 1993;8:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE. What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Res. 1998;28:309–369. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The incentive sensitization theory of addiction: some current issues. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2008;363:3137–3146. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MJF, Berridge KC. Instant transformation of learned repulsion into motivational “wanting. Curr Biol. 2013;23:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S, Sandstrom SM, Denenberg VH, Palmiter RD. Distinguishing whether dopamine regulates liking, wanting, and/or learning about rewards. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:5–15. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. The reward signal of midbrain dopamine neurons. Physiology (Bethesda) 1999;14:249–255. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1999.14.6.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Getting formal with dopamine and reward. Neuron. 2002;36:241–263. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00967-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Li CS. Imaging stress-and cue-induced drug and alcohol craving: association with relapse and clinical implications. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26:25–31. doi: 10.1080/09595230601036960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg EE, Keiflin R, Boivin JR, Witten IB, Deisseroth K, Janak PH. A causal link between prediction errors, dopamine neurons and learning. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:966–973. doi: 10.1038/nn.3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen M, Barrett AC, Negus SS, Caine SB. Cocaine versus food choice procedure in rats: environmental manipulations and effects of amphetamine. J Exp Anal Behav. 2013;99:211–233. doi: 10.1002/jeab.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tindell AJ, Smith KS, Berridge KC, Aldridge JW. Dynamic computation of incentive salience: “wanting” what was never “liked”. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12220–12228. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2499-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall BJ, Kearns DN. Reinstatement in a cocaine versus food choice situation: reversal of preference between drug and non-drug rewards. Addict Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/adb.12054. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waelti P, Dickinson A, Schultz W. Dopamine responses comply with basic assumptions of formal learning theory. Nature. 2001;412:43–48. doi: 10.1038/35083500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks JR. Experimental morphine addiction: Method for automatic intravenous injections in unrestrained rats. Science. 1962;138:143–144. doi: 10.1126/science.138.3537.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Intravenous drug self-administration: a special case of positive reinforcement. In: Bozarth MA, editor. Methods of Assessing the Reinforcing Properties of Abused Drugs. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1987. pp. 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:483–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager LM, Robinson TE. A classically conditioned cocaine cue acquires greater control over motivated behavior in rats prone to attribute incentive salience to a food cue. Psychopharmacology. 2013;226:217–228. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2890-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]