Abstract

Written language is an evolutionarily recent human invention whose neural substrates cannot, therefore, be determined by the genetic code. How, then, does the brain incorporate skills of this type? One possibility is that written language is parasitic on evolutionarily older skills such as spoken language, while another is that dedicated substrates develop with expertise. If written language is parasitic on spoken language, then acquired deficits of spoken and written language should necessarily co-occur. Alternatively, if there are at least some dedicated written language substrates, these deficits may (doubly) dissociate. We report on five individuals with aphasia, documenting a double dissociation in which the production of affixes (e.g., jumping) is disrupted in writing but not speaking, or vice versa. The findings reveal considerable independence of the written and spoken language systems in terms of morpho-orthographic operations. Understanding these properties of the adult orthographic system has implications for the education and rehabilitation of written language.

The neurologist Hermon Gordinier began his paper to the 1903 Annual Meeting of the New York State Medical Society as follows: “No subject in neurology has attracted more attention or excited more discussion than agraphia….” (p. 90). Given the scant research on written language production over much of the last century, one might wonder about this great interest in writing deficits. The reason was that neurologists (the cognitive and neural scientists of the time) understood that written language, as a recent human invention, could not be instantiated in the brain in dedicated neural circuitry on the basis of the genetic blueprint. Therefore, agraphia provided an important opportunity to investigate whether these functions are necessarily co-instantiated with evolutionarily older functions such as spoken language, motor or visual skills or if, instead, the human brain does instantiate recently acquired neural functions in dedicated neural substrates. They assumed that if written language skills are intrinsically parasitic on language/motor substrates, they should not dissociate from spoken or motor skills under conditions of neural injury – hence their interest in agraphia and its relationship to language and motor deficits.

The relationship between the neural substrates supporting writing compared to language and action can be considered from peripheral motor levels of processing to more abstract morphological, syntactic and semantic ones. Until the early 20th century, the focus was largely on the motor aspects, with the giants of neurology – including Wernicke, Lichtheim, Hughlings Jackson, Dejerine, Charcot and Exner – heatedly debating whether or not speech and writing shared the same or distinct cortical centers in the frontal lobe. In this paper, we consider the role of language modality at higher levels of language processing, specifically examining morphological processing. We report on a set of cognitive neuropsychological cases who exhibited greater disruption of morphological processes in writing compared to speech, or vice versa. The findings reveal a brain that can neurally instantiate novel cognitive functions, such as written language, with considerable independence from the evolutionarily older functions and substrates from which they likely originated. For written language, this independence is not limited to sensory-motor levels, but extends to higher levels of language representation.

The relationship between written and spoken language has been most studied in the context of phonological recoding in reading with researchers investigating if written forms are necessarily converted to phonological forms prior to comprehension. The preponderance of findings has shown that although phonological forms are activated automatically during reading (e.g., Rastle & Brysbaert, 2006), phonological recoding is not strictly necessary for comprehension in literate adults—at least not for single words (e.g., Coltheart & Coltheart, 1997). A complementary question in written word production considers whether access to the phonological form is necessary for retrieving a word’s spelling. Here also, the psycholinguistic evidence indicates spoken forms are often active during spelling and may influence spelling performance. For example, studies have found that when individuals are trying to write a word, the simultaneous presentation of a distractor word with a similar/same sound results in faster writing times (relative to an unrelated distractor) than does a distractor with only similar spelling (Zhang & Damian, 2010; Qu et al., 2011). However, as these authors note, the results do not imply that the phonological activation is necessary for accurate single word spelling. In this regard, the cognitive neuropsychological data are especially relevant as they can provide evidence regarding whether a specific process is required for a particular task. Rapp et al. (1997) described a brain-damaged individual who orally named pictures producing a semantically related word (comb → ‘brush”) while, nonetheless, correctly writing COMB. This indicates that the conceptual/semantic system can make direct contact with correct word spellings, even if it fails to access the correct spoken word forms, revealing that phonological mediation is not necessarily required in written word production. A number of such cases have been reported, involving not only opaque languages such as English and Chinese (Caramazza & Hillis, 1990; Hanley & McDonnell, 1997; Bub & Kertesz, 1982; Hier & Mohr, 1977; Kemmerer, Tranel & Manzel, 2005; Law, Wong & Kong, 2007), but also highly transparent languages such as Spanish, Italian and Welsh (Cuetos & Labos, 2001; Miceli et al., 1997; Tainturier et al., 2001). Additionally, the performance of neurologically intact individuals provides converging evidence. For example, Bonin et al. (1998) found that priming conditions that facilitate spoken word production do not necessarily facilitate their written production and Damian et al. (2011; Experiment 2) found that under certain conditions phonological information may not be active during writing. In sum, phonological information may often be active and influential during spelling but it does so in the context of a system that also allows for independent orthographic processing.

These findings of orthographic independence do not specifically address the question of the linguistic richness of orthographic processes/representations. The question remains: Are orthographic processes limited to the retrieval of the letter strings that comprise word spellings or are other aspects of language knowledge available and operational within the orthographic system? Of relevance are cognitive neuropsychological findings revealing that spelling processes are sensitive to grammatical category. For example, one grammatical category (verbs) may be especially disrupted in writing compared to speaking (Caramazza & Hillis, 1991; Hillis, Rapp & Caramazza, 1999; Rapp & Caramazza, 1998), or individuals may exhibit contrasting difficulties in writing nouns but in speaking verbs (Caramazza & Hillis, 1990; Rapp & Caramazza, 2002). The finding that the same pattern is not observed in both writing and speaking indicates that the orthographic system can independently represent an abstract linguistic property such as grammatical category.

Grammatical category is used by morphological processes in constraining possible word forms, allowing English nouns to bear the suffix –s (shirts) but not the suffix –ed (*shirted). This, along with the evidence of grammatical category representation in the orthographic system, prompts the question of whether morphological representation/processing occurs within the orthographic system. The plausibility of morpho-orthography is supported by the observation that word spellings (e.g., in English) are productively conditioned by their morphological structure. For example, when verb stems ending in E combine with vowel-initial suffixes, the E is dropped (LOVE → LOVING, LOVER; ANIMATE → ANIMATION, ANIMATOR). Although analogous to morpho-phonological processes, these operations are specifically expressed over orthographic elements, and thus are distinctly orthographic. However, clear-cut implications do not necessarily follow from these regularities as they might simply represent a limited set of explicitly formulated rules or their productivity might be due to types of lexical analogy posited in phonology (Bybee, 1995)

The morpho-orthography hypothesis proposes a word production system in which, in addition to abstract (amodal) semantic, syntactic and morpho-syntactic operations, there are morpho-phonological and morpho-orthographic processes that operate over modality-specific, morphologically complex representations. An alternative architecture is one in which morphological processes are limited to the spoken production system with an orthographic system that is “blind” to these linguistic properties. In such a system, while lexical phonological representations are morphologically complex, lexical orthographic processes operate over ordered letter strings that are not morphologically structured. Cognitive neuropsychological evidence can contribute to adjudicating between these hypotheses as the morpho-orthographic hypothesis predicts the possibility of morphological deficits affecting one modality but not the other, while the alternative hypothesis predicts that morphological deficits should not occur in the orthographic modality alone.

We report on four individuals who exhibited specific difficulties (deletion and/or substitution errors) in writing inflectional morphemes which contrasted markedly with their largely spared spoken production of the same structures, and we also report on one individual who exhibited the opposite pattern. In addition to documenting the double dissociation of inflectional morpheme production across speech and writing, we also rule out alternative accounts of the data, establishing that the observed inflectional errors cannot be attributed to difficulties in producing word-final segments or explained as lexical substitutions. We conclude that the evidence reveals an orthographic system with high-level linguistic properties that can operate with considerable cognitive and neural independence from the spoken language system.

Participants

All testing was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board and participants were paid for their participation in the research.

All five participants experienced language deficits subsequent to left hemisphere strokes. While some information is summarized in Table 1, detailed descriptions are included in previous reports focusing on other aspects of their language deficits (AES: Fischer-Baum & Rapp, 2012; DHY: Buchwald & Rapp, 2009; KSR: Rapp & Caramazza, 2002; PW: Rapp, Benzing, & Caramazza, 1997; VBR: Buchwald, Rapp & Stone, 2007). The five participants were identified for this study over a fifteen year period because their performance on a spoken and written sentence production screening test indicated greater difficulty producing inflections in one output modality. Because of the long data-collection time-period some task choices changed over time (e.g., as seen below for word comprehension assessment).

Table 1.

Demographic, lesion and research participation information.

| AES | DHY | KSR | PW | VBR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | Male | Male | Male | Female |

| Handedness | Ambi-dextrous | Right | Right | Right | Right |

| Education (years) | 18 | 16 | 18 | 12.2 | 12 |

| Employment Prior to stroke | Manager of federal agency | Banker | Engineering Ph.D student | Grocery manager | President of family company |

| Age at stroke | 42 | 35 | 44 | 51 | 51 |

| Research onset (time post-stroke) | 8 years | 2 years | 6 months | 1 year | 5 years |

| Lesion (left hemisphere) | IFG, MFG, STG, SG, AG | IFG, PCG, SG, antAG, STG | IFG, STG, MTG ITG, SMG, AG, PCG, PrCG | IFG, MFG PrCG | IFG, PrCG, PCG antAG, SMG, IC |

IFG=inferior frontal gyrus, MFG=middle frontal gyrus, STG=superior temporal gyrus, SG=supramarginal gyrus, AG=angular gyrus, PCG=post-central gyrus, PrCG=precentral gyrus; IC=insular cortex

Speech was impaired to varying degrees across the participants. However, these difficulties did not prevent the participants from spontaneously producing simple sentences that were both intelligible and communicatively successful. The only exception was VBR, whose speech was essentially reduced to single-word utterances. Word writing was also impaired to various degrees across participants and the spelling of nonwords was severely impaired in all participants. Importantly, however, all participants scored within the normal range on single word comprehension tasks, a strong indicator of intact word semantics. AES, DHY and VBR were evaluated with the PPVT (Dunn and Dunn, 1981), scoring at the 58th, 87th and 75th percentiles, respectively. KSR was evaluated with a written synonym judgment task (concrete words) and PW with a picture/word verification task on which they scored 100% and 95% accuracy, respectively.

Methods

Verb Elicitation

For all participants, except VBR, verbs were elicited by showing pictures of simple events and asking participants to produce single sentences to describe the depicted events (e.g., “A horse is jumping a fence”). The same pictures were used for eliciting spoken and written sentences; the number of pictures used was: KSR = 89, PW = 154, DHY = 59, AES = 77. The number of trials varied across participants because the number of items in the sentence production test changed over the years and, for some of the participants, was also affected by the individual’s testing availability. Because VBR had great difficulty in orally producing whole sentences, she was administered two elicitation tasks that only required naming the appropriate verb in the inflected form; both tasks were used for oral and written elicitation. For the picture-based elicitation task VBR was presented with a picture of an action with the written label “Today he, ….” or “Yesterday he, ….” and was asked to complete the sentence with the appropriately inflected verb (e.g., ”jumped;” N = 99). For the second task, VBR produced written or spoken inflected verbs in response to prompts presented orally by the experimenter (e.g., Today he walks, yesterday he also ____; She jumps, they also ________; N = 191). For both tasks, spoken and written responses were obtained in different testing sessions.

Noun Elicitation

Nouns were elicited showing pictures of single or multiple objects to AES, PW and VBR, who were instructed to name each object and the number (e.g., “one cat,” “three cats”) either in writing or orally. Pre-testing showed that quantities were correctly identified by the participants, so any inflectional errors observed were not due to quantity confusions.

Analysis was restricted to regularly inflected nouns and verbs. When verbs were produced with auxiliaries (e.g., “is moving”), only the main verb was analyzed. The analysis considered whether or not verbs and nouns were produced with correct inflections. Inflectional errors consisted of either incorrect or omitted inflections (e.g., picture of two cats → “two CAT”; picture of a boy catching a ball → “is CATCHES”). Because the picture-based elicitation task used with AES, DHY, KSR and PW was somewhat open ended and allowed for variability in the length and complexity of sentences produced, the number of verb responses varied across output modality and participants. The number of verbs analyzed in the spoken and written modalities respectively was: AES: 89/88; DHY: 65/63; KSR: 95/87; PW: 178/112; and VBR: 280/290 (combining the two elicitation tasks). For nouns, equal numbers were analyzed in each modality (AES: 64; PW: 60; VBR: 98).

Results

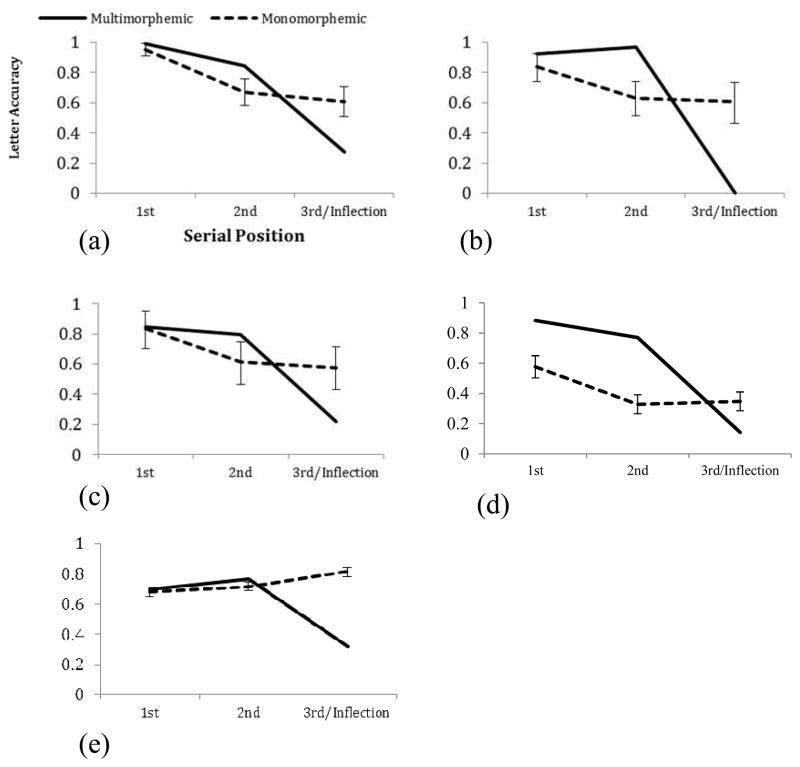

The results reveal clear-cut dissociations in inflectional accuracy across spoken and written modalities for both verb and noun inflections (Figure 1 and Table 2). Inflections were produced significantly more accurately by AES, DHY, KSR, and PW in spoken compared to written responses, with effect sizes ranging from 16.4 to 57.9%. These individuals were highly accurate in producing inflections in the spoken modality, with accuracies ranging from 92–100%. In contrast, VBR showed the opposite pattern, producing inflections significantly more accurately in written (97%) compared to spoken responses (42%).

Figure 1.

Accuracy with verb inflections (left) and noun inflections (right) in spoken and written production. While inflections were produced more accurately in speaking than writing by KSR, PW, DHY and AES, a complementary pattern was exhibited by VBR. See Table 2 for details of the statistical evaluation.

Table 2.

Accuracy on (combined) verb and noun inflections for spoken and written words

| % Correct Inflections/Modality | Comparison (Spoken vs. Written) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spoken | Written | Chi-square | Effect size | [Confidence intervals] | |

| DHY | 92% | 52% | χ2(1)=25.6* | 39.9% | [26.0 –53.9] |

| KSR | 96% | 80% | χ2(1)=11.3* | 15.3% | [6.1 – 24.6] |

| AES | 100% | 84% | χ2(1)=27.4* | 16.4% | [10.6 – 22.3] |

| PW | 99% | 41% | χ2(1)=177.8* | 57.9% | [50.4 – 65.4] |

| VBR | 42% | 97% | χ2(1)=281.9* | −55.6% | [−50.4 – −60.8] |

p < .001

In writing, inflection omissions formed the majority of the inflectional errors produced for both verbs and nouns (AES: 17/25, 68%; DHY: 30/30, 100%; KSR: 11/17, 64%; PW: 101/107, 94%), though affix-substitutions were also observed for all four of these individuals (KSR: slicing → SLICES, PW: drives → DRIVER, AES: perplexed → PERPLEXES). A similar pattern was observed for VBR whose spoken inflectional errors consisted of 59% (94/158) inflection deletions (two shirts → “two shirt”), with the remaining errors consisting of inflection substitutions (e.g., reached → “reaching”). We also note that the difficulties in producing morphemes in the affected modality were not observed on the stems of the same responses. Ignoring minor articulatory (skiing → /sliɪŋ/) or spelling errors (palette → PALLETTE), the rate of lexical substitution errors was very low (AES: 4%, DHY: 2%, PW: 13%, KSR: 10% and VBR: 8%).

The results reveal clear and striking dissociations in the production of inflections across spoken and written output modalities. The fact that inflectional morphology is correctly produced in one modality allows us to infer that higher-level amodal semantic, syntactic and morphological processes were intact, and that the difficulties arose at a modality-specific level. However, before concluding that the findings do, in fact, reflect modality-specific differences in morphological processing, two alternative hypotheses need to be evaluated. One considers if the apparent inflectional errors could be due to especial difficulties with word-final segments, while the other considers if these errors could correspond simply to the mis-selection of formal lexical neighbors of the target words during lexical retrieval.

Analysis 1: Word-position errors?

Cases have been reported with higher error rates in final compared to initial positions in writing (e.g., Costa et al., 2011; Schiller et al., 2001; Ward & Romani, 1998) as well as speaking (e.g., Olson, Romani & Halloran, 2007). Could greater vulnerability of word-final positions explain the inflectional errors observed here? This hypothesis predicts that errors should increase toward word endings not only in inflected words (carts) but also in mono-morphemic words of comparable length (trust). A Monte Carlo analysis was carried out to compare the positional error probabilities for inflected and mono-morphemic errors. We only examined responses from the modality in which participants produced inflections less accurately, excluding responses with semantic errors on the stems (pulling → “lifting”). The numbers of multi-morphemic words that were analyzed varied across participants as follows: AES = 32; DHY = 29; KSR = 20; PW = 94; VBR = 398. Mono-morphemic word errors were obtained from a variety of tasks including single picture naming, spelling to dictation, and the sentence elicitation task that was the source of verb errors. For VBR, the source of mono-morphemic errors included spoken picture naming and elicitation tasks. The numbers of monomorphemic errors in each error pool were: AES = 96, DHY = 131, KSR = 144, PW = 309 and VBR = 224. To make mono and multi-morphemic words more comparable we used only multi-morphemic targets that ended with consonant clusters attested in mono-morphemic words (e.g., the cluster /st/ at the end of “passed” occurs in mono-morphemic words “best” or “toast” while the cluster/rkt/ at the end of “worked” never occurs in mono-morphemic words).

For each participant, on each of the 10,000 runs of the analysis, each inflected word error was randomly paired with a mono-morphemic word error produced in response to a target word of the same length. For example, DHY’s target-error pair jumping → JUMP was randomly paired with the mono-morphemic error calorie → CALARIA on one run and with vampire → VIMPARE on another run. Error positions were normalized to permit comparisons across different word lengths. Normalization was based on the inflected words, with segments assigned one of three bins—the 1st half of the stem, the 2nd half of the stem, and the inflection. For example, for the writing error jumping → JUMP, the 1st bin (JU) and the 2nd bin (MP) were both credited with 2/2 letters correct, while the inflection bin (ING) was credited with 0/3 letters correct because of the omission of the inflection. Letter positions were similarly binned for the errors on mono-morphemic words. For example, for the error CALARIA, the bin assignment of letter positions was comparable to that of JUMPING (CA in 1st bin, 2/2 letters correct; LO in 2nd bin, 1/2 letters correct; RIE in 3rd bin, 2/3 letters correct. This process provided a distribution of errors across letter position for mono-morphemic errors against which the observed error distributions across letter position for the “inflectional” error responses could be compared

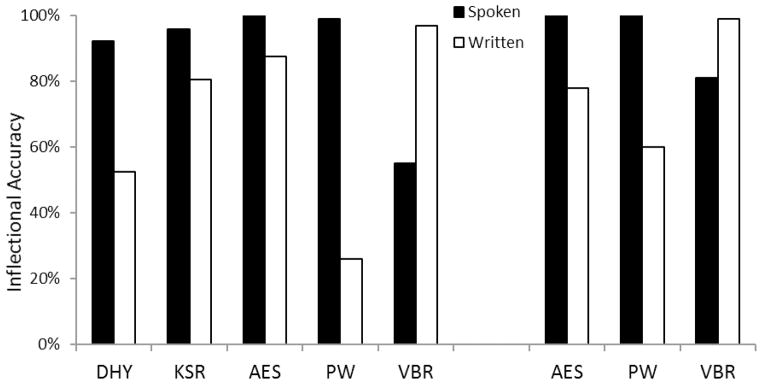

The results are reported in Figure 2. As can be seen, segment errors occurred across all positions for both word types, indicating that errors were not limited to inflections. However, for the inflected words, stem segment accuracy was markedly and statistically greater than inflection segment accuracy (AES: 91%/27%; PW:82%/14%; KSR: 95%/22%; DHY: 95%/0%; VBR: 73%/32%; chi-square p-values all <.0001) More importantly in terms of evaluating the “word final hypothesis”, all participants were less accurate with segments (letters or phonemes) in the “inflectional bin” compared to segments occurring in the corresponding final positions of mono-morphemic words (AES: 27% vs. 61%; DHY: 0% vs. 60%; PW: 14% vs. 34%; KSR: 22% vs. 57%; VBR: 32% vs. 81%). In none of the 10,000 runs of the Monte Carlo analysis was accuracy as low as or lower than that observed in final position for multi-morphemic errors ever observed for mono-morphemic errors (ps < .0001). In fact, the hypothesis that inflectional errors are nothing more than word final errors receives no support from this analysis.

Figure 2.

Distribution of errors across serial position for multi-morphemic and length-matched mono-morphemic errors. Segment accuracy is scored in three bins, representing (for multi-morphemic words) the first half of the stem (1st), the second half of the stem (2nd) and the inflection (3rd/inflection). Mono-morphemic error binning corresponded to the same serial positions as in the matched multi-morphemic items. The error bars reflect bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals around the mean for the mono morphemic error distributions. Written responses are presented for AES (a), DHY (b), KSR (c), and PW (d); spoken responses for VBR (e). For all participants, errors occurred significantly more frequently in final positions for multi-morphemic versus mono-morphemic words (p < .0001).

Analysis 2: Lexical neighbor errors?

While we do not have a complete understanding of the characteristics of word neighbors, it is generally agreed that neighbors share: (1) a large proportion of letters or phonemes, especially the initial segment, and (2) the grammatical category (see Goldrick, Folk & Rapp, 2010; Dell, Oppenheim & Kittredge, 2008). Given that inflectional errors exhibit these same features, it is appropriate to ask if the inflectional errors we observed corresponded simply to neighbor errors. In other words, could it be the case that during lexical selection the participants mis-selected word neighbors and that inflected forms were simply one of the many formal neighbors in the set? In that case, the probability of the inflectional error tying → TIED should match the probability with which the inflectional neighbors occur in the neighborhoods of the target words. This prediction was evaluated with verbs, as these were tested with all participants.

For this analysis, we first determined the set of neighbors of each target verb for which an apparent inflectional error was produced. As illustrated in Table 3, for each word that had resulted in a lexical error (any real word error), neighbors were defined as all words that: (a) were within +/− 10% of the target-error similarity in terms of segment length and percentage of shared segments, (b) shared the same initial segment as the target, and (c) were verbs. For each lexical error, neighbors of the target word with these characteristics were identified in the CELEX database (Baayen, Piepenbrok & Van Rijin, 1993). Note that for this analysis, only errors in which the stem was produced correctly were included (as responses with stem errors, such as WALKED → WOLK, could not occur in the neighbor set).

Table 3.

Monte Carlo analysis procedure for Analysis 2 (lexical neighbor errors) illustrated with the written error tying → TIED

| Observed Written Error | Matched Candidate Errors in CELEX |

|---|---|

| TIED (target: tying) | TIES, TIED, TIME, TRYING, TEND… (N = 69) |

| Observed Error Characteristics | Candidate Error Characteristics |

|

| |

| (a) 4 letters long | (a) 4–6 letters long |

| (b) 4/9 letters (44%) shared with tying | (b) 34–54% letters shared with tying |

| (c) verb | (c) verb |

| (d) starts with letter T | (d) starts with letter T |

| N Morphological Errors/Total Matched Candidate Errors 2 (TIES, TIED)/69 | |

A Monte Carlo analysis was used to determine the chance rate of selecting an inflected form (tying → TIES) from the neighbor set. On each of the 10,000 runs of the analysis conducted for each participant and for each target word (e.g., tying), a word from the neighbor set (see Table 3) was randomly selected as candidate error. The proportion of inflectional errors (tying → ties, tied) selected by this random process were then tabulated.

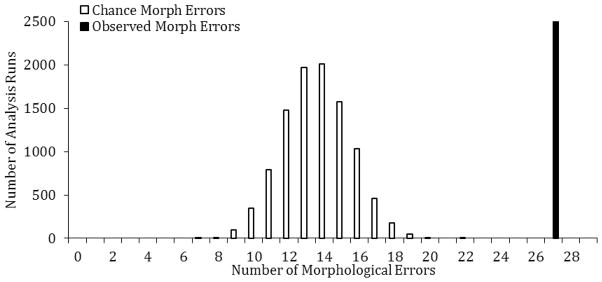

The probability distribution of the expected inflectional errors (see example in Figure 3) was used for significance testing. The results (Table 4) reveal that the number of inflectional errors produced by the participants significantly exceeded the number of inflectional errors observed in the 10,000 runs of the Monte Carlo analysis that instantiated the hypothesis that the observed errors simply corresponded to the mis-selection of lexical neighbors. These findings clearly reveal that the observed inflection errors cannot be accounted for in terms of a neighborhood effect “in disguise.”

Figure 3.

The number of morphological errors actually produced by DHY (black bar) and the distribution of the numbers of morphological errors expected by chance for DHY’s data set, as determined by 10,000 runs of a Monte Carlo analysis (white bars). The results reveal that DHY’s morphological errors were significantly more frequent than expected from a random sampling of orthographic neighbors (p < .0001). Similar distributions were obtained for the other participants, and findings are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Rates of morphological errors observed compared to those expected under the hypothesis that the observed inflected errors were the result of mis-selection of words from phonological/orthographic neighborhoods

| Modality | N (%) Morphological Errors | Observed vs. Expected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed/Lexical Errors | Expected - Mean | |||

| AES | Written | 12/17 (71%) | 3.8 (22%) | p < .0001 |

| KSR | Written | 9/13 (69%) | 3.0 (23%) | p < .0001 |

| DHY | Written | 27/29 (93%) | 13.7 (47%) | p < .0001 |

| PW | Written | 44/58 (76%) | 9.1 (16%) | p < .0001 |

| VBR | Spoken | 225/306 (74%) | 115.3 (38%) | p < .0001 |

General Discussion

The finding of modality-selective difficulties in producing inflected forms provides strong support for the morpho-orthography hypothesis according to which inflectional processes operate, not only at abstract levels and within the spoken language system, but also within the orthographic system. The reported findings represent a challenge for a contrasting architecture in which morphological operations are limited to the spoken modality because, in such a system, the orthography lacks the representations/processes needed to yield errors in which inflections (rather than random letter sequences) are specifically deleted or substituted. The double dissociation in which the production of inflections is more severely disrupted in writing than speaking, or vice versa, supports the independence of the modality-specific morphological operations. The fact that the observed deficits cannot be explained as difficulties with word endings or as resulting from the mis-selection of formal neighbors strengthens the claim that the affected operations are indeed morphological. As generally recognized, double dissociations reduce the likelihood that the observed dissociations result from irrelevant variables such as task difficulty or attentional demands. If morphological processing were more demanding in the written modality, we would not expect the complementary pattern of greater difficulty with inflections in spoken vs. written production.

The presented evidence is consistent with the small number of previous reports indicating sensitivity to morphological structure in the written production system. Badecker et al. (1990) described individuals with orthographic working memory deficits with lower error rates for morphologically complex words vs. mono-morphemic words and error distributions that respected stem/inflection boundaries. Berndt and Haendiges (2000) reported an individual who exhibited greater difficulties with verb inflections in writing versus speaking, while Badecker et al. (1996) described a complementary difficulty in writing word stems but not affixes. Finally, with neurologically intact individuals, Kandel et al. (2012) found that writing times for letters preceding morpheme boundaries were longer in suffixed than in pseudo-suffixed words.

Chomsky and Halle (1968) famously remarked that “English orthography, despite its often cited inconsistencies, comes remarkably close to being an optimal orthographic system for English” (p. 49). They were referring to the fact that, among other things, morphological information is sometimes more consistently represented in the orthography than in the phonology. For example, the plural morpheme is consistently spelled with S in CATS and DOGS despite being realized with different phonemes (cat/s/ and dog/z/). Regardless of one’s view of the optimality of English orthography, their position highlights that the independence of orthographic representation extends to higher-level aspects of linguistic representation. Although the orthography is a representational system that clearly originated in the phonological system, the evidence we have reported reveals its capacity for the independent representation of linguistic information. This does not imply that the phonological and orthographic systems always function in isolation, as there is also evidence that both are active during production in either modality (Damian & Bowers, 2003; Damian, Dorjee &Stadthagen-Gonzalez, 2011). Relatedly, one might wonder if morpho-orthography occurs only in “deep orthographies” with unpredictable phonology-orthography mappings. The neuropsychological report (Miceli et al., 1983) of an Italian individual who produced morphological errors in spoken but not written sentence production suggests that orthographic depth may not be critical, though more research is warranted.

Presumably, the capacity for modality-specific orthographic processing at higher linguistic levels develops with increasing expertise and adds to the efficiency and speed of written word production. Understanding that the “end state” of the written production system involves orthographic representations and processes sensitive to the morphological structure of words is relevant for literacy instruction and rehabilitation. Considerable research has examined the relationship between general morphological skills and literacy development (Nagy, Beninger & Abbott, 2006), while less has specifically examined the development of morpho-orthography (but see, Egan & Tainturier, 2011; Treiman & Cassar, 1996). Learning and rehabilitation experiences that target orthographic morphological structures and processes may contribute to developing the type and level of expertise of the adult writer.

In conclusion, one can only surmise that Gordinier, Wernicke, and colleagues would have responded with great interest to the evidence presented here revealing the brain’s capacity to instantiate linguistically sophisticated features of written language with considerable neural independence from evolutionarily older skills such as spoken language.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matt Goldrick for his assistance with Analysis 2, Isabelle Barriere for her input and NIDCD grant DC012283 to B. Rapp.

Footnotes

Author contributions. B. Rapp developed the experimental question and experimental design in collaboration with M. Miozzo. B. Rapp and S. Fischer-Baum designed and carried out the Monte Carlo analyses. The three authors contributed substantively to the data collection and the writing of the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

References

- Baayen H, Piepenbrock R, van Rijn H. The CELEX database on CD-ROM. Linguistic Data Consortium; Philadelphia, PA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Badecker W, Hillis A, Caramazza A. Lexical morphology and its role in the writing process: Evidence from a case of acquired dysgraphia. Cognition. 1990;35(3):205–243. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(90)90023-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badecker W, Rapp B, Caramazza A. Lexical morphology and the two orthographic routes. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1996;13(2):161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt RS, Haendiges AN. Grammatical class in word and sentence production: Evidence from an aphasic patient. Journal of Memory and Language. 2000;43(2):249–273. [Google Scholar]

- Bonin P, Fayol M, Peereman R. Masked form priming in writing words from pictures: Evidence for direct retrieval of orthographic codes. Acta Psychologica. 1998;99(3):311–328. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6918(98)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bybee J. Regular morphology and the lexicon. Language and Cognitive Processes. 1995;10:425–455. [Google Scholar]

- Bub D, Kertesz A. Evidence for lexicographic processing in a patient with preserved written over oral single word naming. Brain. 1982;105(4):697–717. doi: 10.1093/brain/105.4.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald AB, Rapp B, Stone M. Insertion of discrete phonological units: An articulatory and acoustic investigation of aphasic speech. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2007;22(6):910–948. [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald A, Rapp B. Distinctions between orthographic long-term memory and working memory. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 2009;26(8):724–751. doi: 10.1080/02643291003707332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramazza A, Hillis AE. Lexical organization of nouns and verbs in the brain. Nature. 1991;349(6312):788–790. doi: 10.1038/349788a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramazza A, Hillis AE. Where do semantic errors come from? Cortex. 1990;26(1):95–122. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coltheart M, Coltheart V. Reading comprehension is not exclusively reliant upon phonological representation. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1997;14(1):167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Costa V, Fischer-Baum S, Capasso R, Miceli G, Rapp B. Temporal stability and representational distinctiveness: Key functions of orthographic working memory. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 2011;28(5):338–362. doi: 10.1080/02643294.2011.648921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuetos F, Labos E. The autonomy of the orthographic pathway in a shallow language: Data from an aphasic patient. Aphasiology. 2001;15(4):333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Damian MF, Bowers JS. Effects of orthography on speech production in a form-preparation paradigm. Journal of Memory and Language. 2003;49(1):119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Damian MF, Dorjee D, Stadthagen-Gonzalez H. Long-term repetition priming in spoken and written word production: Evidence for a contribution of phonology to handwriting. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2011;37(4):813. doi: 10.1037/a0023260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell GS, Oppenheim GM, Kittredge AK. Saying the right word at the right time: Syntagmatic and paradigmatic interference in sentence production. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2008;23(4):583–608. doi: 10.1080/01690960801920735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LM. PPVT. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Egan J, Tainturier MJ. Inflectional spelling deficits in developmental dyslexia. Cortex. 2011;47(10):1179–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Baum S, Rapp B. Underlying cause(s) of letter perseveration errors. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50(2):305–318. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldrick M, Folk JR, Rapp B. Mrs. Malaprop’s neighborhood: Using word errors to reveal neighborhood structure. Journal of Memory and Language. 2010;62(2):113–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordinier HC. Arguments in favor of the existence of a separate centre for writing. American Journal of Medical Sciences. 1903;126(3):490–503. [Google Scholar]

- Halle M, Chomsky N. The Sound Pattern of English. New York: Harper & Row; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JR, McDonnell V. Are reading and spelling phonologically mediated? Evidence from a patient with a speech production impairment. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1997;14(1):3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hier DB, Mohr JP. Incongruous oral and written naming: Evidence for a subdivision of the syndrome of Wernicke’s aphasia. Brain and Language. 1977;4(1):115–126. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(77)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis AE, Rapp BC, Caramazza A. When a rose is a rose in speech but a tulip in writing. Cortex. 1999;35(3):337–356. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70804-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel S, Spinelli E, Tremblay A, Guerassimovitch H, Álvarez CJ. Processing prefixes and suffixes in handwriting production. Acta Psychologica. 2012;140(3):187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemmerer D, Tranel D, Manzel K. An exaggerated effect for proper nouns in a case of superior written over spoken word production. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 2005;22(1):3–27. doi: 10.1080/02643290442000013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law SP, Wong W, Kong A. Direct access from meaning to orthography in Chinese: A case study of superior written to oral naming. Aphasiology. 2006;20(6):565–578. [Google Scholar]

- Miceli G, Mazzucchi A, Menn L, Goodglass H. Contrasting cases of Italian agrammatic aphasia without comprehension disorder. Brain and Language. 1983;19(1):65–97. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(83)90056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miceli G, Benvegnu B, Capasso R, Caramazza A. The independence of phonological and orthographic lexical forms: Evidence from aphasia. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1997;14(1):35–69. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy W, Berninger VW, Abbott RD. Contributions of morphology beyond phonology to literacy outcomes of upper elementary and middle-school students. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98(1):134. [Google Scholar]

- Olson AC, Romani C, Halloran L. Localizing the deficit in a case of jargonaphasia. Cognitive neuropsychology. 2007;24(2):211–238. doi: 10.1080/02643290601137017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Q, Damian MF, Zhang Q, Zhu X. Phonology contributes to writing: Evidence from written word production in a nonalphabetic script. Psychological Science. 2011;22(9):1107–1112. doi: 10.1177/0956797611417001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp BC, Benzing L, Caramazza A. The autonomy of lexical orthography. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1997;14:71–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp B, Caramazza A. A case of selective difficulty in writing verbs. Neurocase. 1998;4(2):127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp B, Caramazza A. Selective difficulties with spoken nouns and written verbs: A single case study. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2002;15(3):373–402. [Google Scholar]

- Rastle K, Brysbaert M. Masked phonological priming effects in English: Are they real? Do they matter? Cognitive Psychology. 2006;53(2):97–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller NO, Greenhall JA, Shelton JR, Caramazza A. Serial order effects in spelling errors: Evidence from two dysgraphic patients. Neurocase. 2001;7(1):1–14. doi: 10.1093/neucas/7.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tainturier MJ, Moreaud O, David D, Leek EC, Pellat J. Superior written over spoken picture naming in a case of frontotemporal dementia. Neurocase. 2001;7:89–96. doi: 10.1093/neucas/7.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiman R, Cassar M. Effects of morphology on children’s spelling of final consonant clusters. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1996;63(1):141–170. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1996.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J, Romani C. Serial position effects and lexical activation in spelling: Evidence from a single case study. Neurocase. 1998;4(3):189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Damian MF. Impact of phonology on the generation of handwritten responses: Evidence from picture-word interference tasks. Memory & Cognition. 2010;38(4):519–528. doi: 10.3758/MC.38.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]