Abstract

Background:

Caring is a fundamental issue in the rehabilitation of a person with mental illness and more so for people with severe mental illness. The lack of adequate manpower resources in the country is adding and enlisting the responsibility of providing care on the families to provide physical, medical, social and psychological care for their severely unwell mentally ill people.

Aim of the Study:

To examine the load of caregiving with reference to the types of care during the symptomatic and remission phases of severe mental illness and the various ways in which caregivers adapt their lives to meet the needs of people with severe mental illness.

Materials and Methods:

The present research draws its data from the 200 families with mental illness in Andra Pradesh and Karnataka in India. The data presented in the study was collected from interviews using an interview schedule with open-ended questions.

Results:

The study diffuses the notion of ‘care’ as ‘physical’, ‘medical, ‘psychological’ and ‘social’ care. The present article focuses on the caregiving roles of the caregivers of people with schizophrenia, affective disorders and psychosis not otherwise specified (NOS) and found that the caregiving does not differ much between the different diagnosis, but caregiving roles changes from active involvement in physical and medical care to more of social and psychological care during the remission.

Conclusion:

The study records the incredulous gratitude of caregivers at being acknowledged for the work they do. In that regard, the study itself provides a boost to the morale of tired, unacknowledged caregivers.

Keywords: Caregiver, cargiving experiences, caregiver load, people with severe mental illness

INTRODUCTION

Caring is a fundamental issue in the treatment for PersonsWith Severe Mental Disorder (PWSMD). The onset of a mental illness in any family is often, and understandably, a time of turmoil. Most families are ill-prepared to deal with the initial onset of severe mental disorder in their family member.[1] Families generally have little knowledge of mental illness, and find that they not only have to deal with the ups and down of illness but also need to deal with the stigma, and attitudes in the community.[1,2] Caring PWSMD can be a devastating stressor in any family, regardless of its strengths and resources available for coping with a family member with severe mental illness.[3] The presence of PWSMD impacts family members in several ways, disrupts the family functioning, affects the occupational and social functioning, and same been reported extensively in the literature as burden of care.[4,5,6] Both bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia are associated with a considerable degree of perceived burden by caregivers.[7,8,9,10,11] The family provides considerable amount of care for their mentally ill relatives even though they experience burden[12,13], families view caregiving as their sole responsibility toward their offspring with mental illness. Research studies in India have documented that the vast majority of PMSWD live with their family members, who are required to provide care and support for the extended periods of time.[14,15,16] Most of the time the caregiver's efforts are neither recognized nor acknowledged and seen as plentiful resources freely available for caring people with mental illness.[17]

In India, the majority of PWSMD stay with their families.[14,15] Caregivers have a major role to play in the re-socialization, vocational and social skills training of the PWSMD, not only because of close family ties that exist in these traditional societies but also because developing countries lack rehabilitation professionals to deliver these services.[6] Carer burden is exacerbated by issues of poverty and illiteracy.[18] Such burden manifests in reduced caregiver well-being[19], which admittedly depends in part on caregiver factors such as caregiving style.[20] In turn, as caregivers are less able to provide support to their ill relatives, their relatives’ well-being, and ability to remain in the community suffer.[21,22] It is well-researched and proved that community-based interventions fasters the rehabilitation of PWSMD[17,23,24,25], same led developing and developed countries to invest more on community mental health programme rather than institutional care.[17,25,26,27] The emergence of community-based methods of care and the decrease in economic resources have led to a shift in the responsibility for the care of the ill individual from the institution to the family.[28,29] The paucity of mental health care has resulted families to shoulder more responsibilities of caring their mentally ill family member[17], whether it was by choice or our cultural influence or due to the lack of facilities, it is difficult to conclude, though there are some evidence to support that family involvement in care was and continues to be a preference of families.[30,31]

It is unfortunate that the experiences of the families with different types of severe mental illness have not been adequately studied and their strengths not been optimally utilized in the recovery of person with severe mental illness. Yet, there is limited holistic understanding, of both the difficult roles they play and the circumstances under which relatives look after persons with severe mental illness, as also the emotional and practical challenges they face through the different phases of the illness. The researchers in this study would like to study the different types of care required for people with different types of severe mental illness. The researchers are trying to find answers to the question of whether the caregiving differs during symptomatic phase and remission phase for people with different types of severe mental illness.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study aims at understanding the profile of the caregivers and the different roles of the caregiver while caring PWSMD. Descriptive research design was used for the present study. The population for the study include all the caregivers of PWSMD in the Mental Health and Development programme1 of Basic Needs India (BNI)2 implemented in partnership with the two non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Karnataka and one NGO in Andra Pradesh in India. The three partners of BNI are medium-sized NGOs working for people with disabilities using community-based rehabilitation (CBR) approach, formed the universe of the study. The partners of BNI are SACRED3 (Ananthapur) in Andhra Pradesh; Gramena Abiyudaya Seva Samastha (GASS)4 (Doddaballapura) and Narendra Foundation (Pavagada)5 in Karnataka. The sample consists of the caregivers of 201 people with severe mental illness (assessed and diagnosed by the psychiatrist in mental health camps/district hospital) availing care services for more than 2 years. All the caregivers of 201 persons with severe mental illnesses were included for the present study.

Measures (developing caregiving checklist)

Thirty life stories written by BNI staff were reviewed, the roles of the caregivers from the life stories during the acute phase of illness and later during their recovery was recorded. The list of caregiving was prepared and circulated among the research team for their comments. The mental health coordinators6 from the three organizations were contacted, brainstormed with them to prepare the list of caregiving provided by the family members. Both the lists were reviewed and an interview schedule was developed for collecting information about caregivers efforts and their role in the well-being of PWSMD. The interview schedule has four domains: Socio-demographic details of persons with mental illness; socio-demographic details of the caregiver; and caregiving: This section lists out four different types of caregiving activities which are classified as physical care, psychological care, medical care and social care; caregivers as resources. The families providing care for their needy mentally ill family member were coded as 1 and those families not providing care is coded as 0. Thus, the caregiving was measured taking the total score. The researchers define physical care, medical, psychological and social care as follows:

Physical care: One of the major symptoms of severe mental disorder (SMD) is deterioration in appearance, hygiene or personal care. This affects their social aspects, as many people would rather alienate themselves from someone who has poor personal hygiene than to tell them how they could improve.

Medical care: Medical care includes care provided through faith healers, black magicians, religious places, etc. Families do shopping with various available resources within community in search of cure. Persons with mental illness (PWMIs) are usually non-compliant with medications because of its treatment duration and side effects. Many would like to discontinue the medication which in turn results in relapse of the illness. The caregivers have to constantly monitor if the medicines are taken or not, their effects, etc.

Psychological care: Changes in thinking, perception, mood and behaviour are characteristic of SMD. It becomes very important to manage the PWSMD when s/he is psychologically and emotionally disturbed.

Social care: The stigma and discrimination associated with mental illness is huge. This manifests in the forms of denial of illness, harmful treatment, social boycott of the PWSMD and the family members, denial of property rights, marriage and legal separations, family members not getting marriage alliance, etc. Caregivers, especially among poor, suffer quite a lot. Caregivers are faced with twin challenges — their own livelihood and caring and managing a PWSMD in the family. Social care is a long-drawn process. This starts from acceptance of the PWSMD by her/his family first and then by the outside world.

Several steps were taken in building capacities of the partner staff on understanding the interview schedule on caregiving. Initially, the partners were consulted about the research study and discussions were held on the importance of recognizing the caregiving roles of the caregiver and use them as resource for the Community Mental Health Programme. The research team trained all the mental health coordinators in their local language for 2 days in understanding the concept of caring for PWSMD and in understanding the interview schedule. The training includes role plays and demonstration of administering the interview schedule. This research created a platform for BNI to capacitate the field staff of the organization on the needs for recognizing caregivers and their roles in the recovery of PWSMD, and to utilize their resources for the programme. The process of data collection was empowering the caregivers in understanding their own role in the recovery process, acted as an intervention in making them realize their role in the rehabilitation of their severely mentally ill family member.

Researchers have defined symptomatic and remission phase as7.

Sample pilot interviews were conducted to helping them to familiarizing with the interview schedule. Finally the mental health coordinators administered the interview schedule after obtaining written consent from the caregivers. The data was coded and entered in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), and used both descriptive statistics and parametric statistical analysis.

RESULTS

The sample equal number of males (101) and females (100), which reflect the general pattern in the population.

The diagnostic categories of mental illness identified were schizophrenia, affective disorders and psychosis. Nearly one-half of them have schizophrenia (47.2%), one-quarter had affective disorder (26.4%) and other quarter (26.4%) had psychosis NOS.

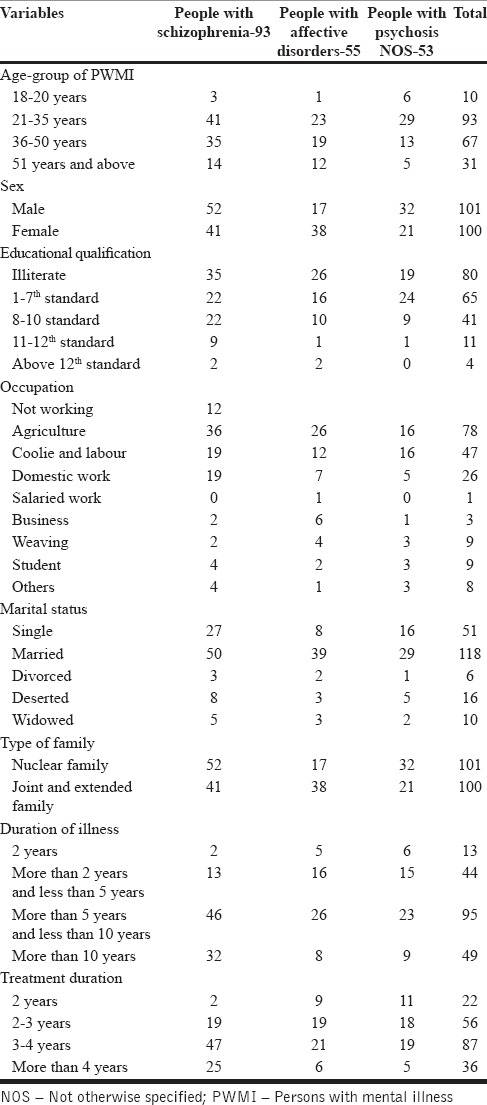

Table 1 describes that nearly half (46.2%) of the PWSMD are in the age-group of 21 to 35 years and a third (31.9) of the sample are in the age-group of 36-50 years. About 15% were over 51 years. Only 5% were between 18 and 20 years of age. Not much difference has been found in terms of the age-group of various diagnosis. With regard to the sex of the respondents, more number of male were found in schizophrenia and psychosis NOS group when compared to affective group, probably because of more number of women with unipolar depression. The table indicates the prevalence of more number of illiterates among women, 40% of women are illiterate. The occupations of PWMIs varied. They seem to be mainly engaged in agriculture (farming), labour work and domestic work. A small number were engaged in small businesses and weaving, not much difference been observed among the different diagnostic categories. There seems to be some variations between male and female occupations. Domestic work is dominated by women, same trend is seen in all the diagnostic categories. Agriculture and weaving seems to be engaged by men more than women. Both men and women are almost equally engaged in coolie or labour work and small businesses. It is quite striking that among those not working, men are more in number, compared to women. Findings related to marital status brings out some interesting results. Majority (57.2%) of persons with mental illness were married. Among those who were single, men were almost double the number of women. Among those widowed, women were more in number. This could be because of the tradition of men remarrying. Divorce and desertion were seen among both men and women in all the diagnostic categories, though women seem to be affected more than men [Table 2].

Table 1.

Distribution of people with mental illness against socio-demographic variables

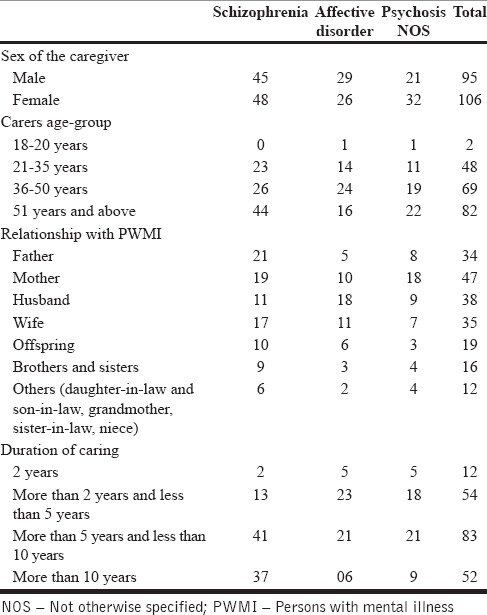

Table 2.

Distribution of caregivers according to their age, relationship and duration of care

All the caregivers hailed from rural India. Women caregivers were more in number (52.7%) compared to men. It is noteworthy that there were 47.3 % of male caregivers. Maybe, within the family, when men need caring, women are there and when women need caring, men are there. This implies the strength of the relationships within the family.

Majority of the caregivers (40.8%) were above the age of 51 years. This indicates the prevalence of aged caregivers. The responsibility of caregiving seems to be more with the older members in the family. Nearly three-fourths (34.3%) of the caregivers were above 36 years upwards, and much beyond 51 years, constituting wives, siblings, their children and their spouses. Only about one-fourth (23.9%) were below 35 years, constitutes spouses and their children.

The data presented bring out that almost all relatives within the family served as caregivers — fathers, mothers, husbands, wives, children, siblings, daughters, sons-in-law, grandmother, sisters-in-law and nieces. It appears that whoever was near the PWSMD took care of them. Majority of the PWSMD (67%) were taken care of by the caregivers for more than 5 years up to 10 years or more. Out of these, a large population was given care over 10 years.

Large number had the illness for more than 5 years, up to 10 years or even more (about 70%). This indicates that most people who were included in the study were having chronic mental illness [Table 3].

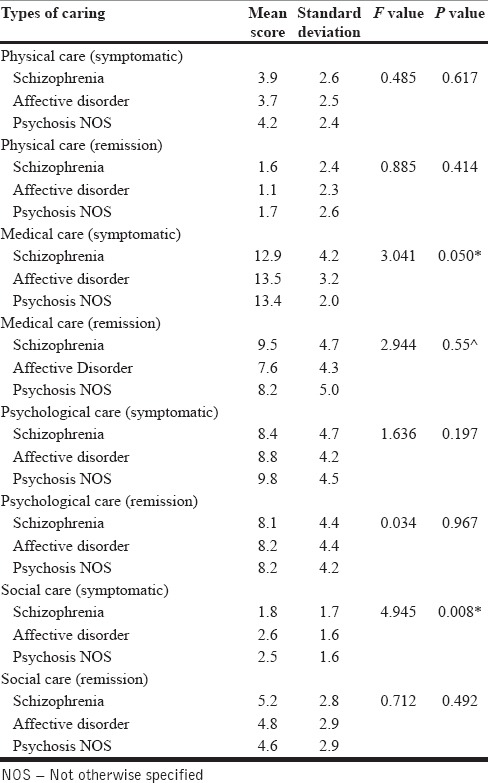

Table 3.

Mean scores of types of care during symptomatic and remission phases for different types of people with severe mental disorders

Care of PWSMD were seen in the present study as four different aspects of caregiving which are all converging — physical care, medical care, psychological care and social care. Each of these four aspects of caregiving was studied in terms of two phases of the lives of PWSMD, namely, the symptomatic and stabilized phase. It could be expected that the load/weight/burden of caregiving would get lighter as and when PWSMD show signs of remission, which essentially means ‘inclusion’ in mainstream development.

Physical care

When the PWSMD was highly symptomatic, s/he required significant amount of physical care which includes brushing teeth, bathing, combing hair, helping natures call and cleaning afterwards, sending for haircut, ensuring s/he wears clean clothes and feeding the person with severe mental illness. During acute phase, s/he is less aware of their physical appearance and personal hygiene. This required the caregiver to be alert all the time and watchful of the PWSMD. The physical caregiving is more are less same for all the types of severe mental illness. But upon treatment, the PWSMD tends to get out of their symptoms and become aware of their physical self. The close observation of mean scores indicates that people with affective disorder requires less support when compared to people with schizophrenia and psychosis NOS however is not statistically significant. Thus, it can be concluded that, in the three diagnostic categories of mental illness, namely, schizophrenia, affective disorder and psychosis, the differences in the mean scores of various aspects and dimensions of caregiving show that with reference to ‘physical care’ during symptomatic phase, the load of caregiving is more or less the same for all three illnesses and during the stabilized phase, the weight of caregiving got reduced for all the illnesses more or less in the same way.

Medical Care

When the PWSMD is symptomatic, s/he requires assistance in taking medicines or reminders to take them; observing and reporting side-effects; approaching faith healers; temple churches, black magicians for recovery; motivating the person with mental illness to undergo treatment and spending money on the same; bringing the person to the camps regularly; if hospitalization is required, then being with the person with mental illness in the hospital and meeting his needs; carers administering the medicines; coming up with tricks, like mixing it with ragi balls, to ensure medicine intake; motivating the person with severe mental illness to take medicines; observing the changes; etc.

But once s/he is in remission, the amount of caregiving reduces, when the PWSMD realizes the importance of treatment and takes the responsibility of taking medicines and attending the camps on their own. However, in certain chronic cases, the caregiving is seen to continue even when the PWSMD is free of symptoms. The mean distribution and the f value indicates the statistically significant difference with regard to medical care during symptomatic and stabilized phase among people with schizophrenia, Affective disorder and psychosis indicating that when symptomatic, people with affective disorder require more medical care than people with schizophrenia or psychosis. Whereas when stabilized, people diagnosed with schizophrenia require more medical care, as compared to people diagnosed with affective disorder and psychosis. In conclusion, ‘medical care’ again, the weight remains more or less the same for the three illnesses during the symptomatic phase and there was reduction of load showing a similar pattern in stabilized phase.

Psychological care

The psychological care for people with severe mental disorders includes: Treating the person with love and affection, caressing the person whenever the person is restless, listening to the person when s/he speaks, comforting the person when upset, confining the person where no one goes (isolating the person), allowing the relatives or others who are nice to the person to come, be with the person and speak to the person, to engage in activities from small tasks to big tasks, listening to the person with mental illness what work he wants to do and if feasible, encouraging him/her to do it and engaging the person with mental illness in household work, decision-making and communication.

With reference to the aspect of psychological care, the difference in mean scores is not significant among different types of severe mental illness and in the two phases of illness. This indicates that psychological caregiving continues even after remission. This implies that the emotional support and care need to be continued for PWMIs so that they gain confidence and strength within themselves for some more time after they get well. The caregivers need to take initiatives and create opportunities for the person to be involved in productive activities. They need to comfort the person, motivate and encourage the person to lead good quality of life. In conclusion, load of ‘psychological care’ for all the three illnesses more or less remained same during symptomatic and stabilized phases — indicating the need for continued emotional care and support for PWSMD.

Social care

The aspect of social care of PWSMD is quite complex as it goes beyond the individual mental strength — namely, making the community understand that his/her behaviour is only due to illness, preventing the community from abusing physically, mentally and sexually, taking the person to religious and social functions of only close relatives, encouraging the person with mental illness to mingle and interact with friends, safeguarding the property rights of person with mental illness, honouring/helping fulfill the wish of the person with mental illness to get married and lead a normal life, not compromising mutual interests and participating in self-help group (SHG) activities.

Social acceptance means ‘social inclusion’. They are enabled to be accepted by the wider community and to participate in the community activities. The data in the table presented shows that ‘social inclusion’ is a complex and hence a long-time process as it requires a change in the perspectives of the community as a whole. The difference in mean scores of different diagnostic groups during the symptomatic and remission phases is negatively significant. This clearly indicates the social care would increase with the remission and continues for a duration not easy discernable. In other words, the activities for enabling social inclusion become a reality only when they are in remission.

The caregivers expressed that they could overcome their problems of giving care to PWMIs by being patience, taking the advice of the field staff, giving medicines regularly and supporting the persons with mental illness in completing their half-done jobs. In one case, the mother severed her relationship with her son because she wanted to care for her daughter who was mentally ill.

DISCUSSION

The socio-demographic profile of the person with mental illness and the caregivers is consistent with that of the earlier studies conducted on the person with mental illness and caregivers in the community settings.[26,29] All caregivers were close family members like parents, spouses, siblings and their children. The present study reveals that more number of caregivers were above the age of 51 years, the responsibility of looking after the PWMI lies on the older family member as they are at home and given the responsibility of caring. This proves that in India, the cultural factors such as strong family ties, family systems, family environment have reduced the burden of care on the state. In India PWMI is always accompanied by the family member as compared to other countries where caregivers are not necessarily family member.[12,14]

Women provide the majority of informal care to their mentally ill people, daughters and daughter-in-laws provide care to their mentally ill parents and to their parents-in-law. It is noted that more number of spouse (husband/wives) do provide care for their mentally ill spouse. The study also reveals that 47.3% of them are male caregivers like husbands, fathers and sons who have taken the responsibility of caring their mentally ill family members. Men do provide care for their ill female family member with the help of the extended families, but the same is not shared or spoken to others and they do not participate in the caregivers meeting. They provide care silently. Most of them were relatives even before marriage (consanguinity). The caregivers play many roles while caregiving: Health provider, care manager, friend, companion, surrogate decision-maker and as an advocate.[1,32] Several studies have proved that the percentage of family or informal caregivers who are women range from 59% to 75%. The average caregiver is a female aged 46 year old, married and working outside the home. Although men also provide assistance, female caregivers may spend as much as 50% more time providing care than male caregivers.[33,34,35] It is often observed that for any consultations or caregivers gathering/meeting, more number of women represents or escorts their family member with mental illness. The representation from the male caregivers is less, mainly because of their engagement in the livelihood activities but men do share the responsibility of providing care for their female mentally ill family member. Even though men do not participate and vocal about the care they provide, they do spend more time for their loved one's having mental illness. The trend of increasing care providers from male family members have been observed in the studies even though most caregivers are women who handle time-consuming and difficult tasks like personal care.[36] But at least 40% of caregivers are men,[36] growing trend demonstrated by a 50% increase in male caregivers between 1984 and 1994.[37] While family members irrespective of gender usually wish to be involved in the care of their loved ones and would appreciate an opportunity.[34]

The present finding concludes that people with all severe mental disorder would require same amount of care during symptomatic phase and load of caring get reduced in the remission for all people with different types of severe mental illness. Very few studies have been conducted to look at the experiences of the caregivers, and many studies have looked more in terms of burden of caregiving people with different forms of severe mental disorders. Some studies suggest that caregivers of schizophrenia suffer same degree of burden when compared to caregivers of affective disorders[38,39] whereas other study suggests that the burden is higher on the caregivers of schizophrenia[8] when compared to the caregivers of affective disorder has been inconclusive.

In the study, researchers have found that people with schizophrenia and psychosis require more medical care even after remission when compared to people with affective disorders. Since no earlier study has compared the caregiving roles for people with schizophrenia, affective disorders and psychosis NOS, it is not possible to compare our findings with the available literature. The PWSMD had been ill for a longer period of time and had been in the community mental healthcare programme with weekly home-based follow-up from the field staff for a minimum period of 2 years. This made the caregivers to realize the need for encouraging their severely mentally ill family member for more socialization and inclusion in the community.

In the present study, the researchers have found that people with schizophrenia, affective disorders and psychosis NOS require same amount of social care during remission phase. This suggests that overall all types of severe mental illness requires same amount of care. The severe mental illness has more negative impact on caregivers because of the continuous illness, being dependent, finding difficult to involve in productive activity and requirement of large amount of care for people with severe mental illness. Caregivers not only need to provide care for people with severe mental illness but also need to face the brunt of stigma associated with the illness. This finding is similar to earlier studies.[40,41,42]

The types of care required also varies; physical care and medical care required more during acute phase/symptomatic phase, psychological care continues, followed by social care even after the person recovers from the illness. Caregivers have to spend more time when their family member is symptomatic as they need to care for their personal hygiene, calm down during emotional outburst and take the brunt of abuse and assaults from their mentally ill family members. Caregivers’ involvement in direct and indirect care changes over time, in response to the stage of illness and treatment, and caregivers must be able to adapt to changes in the amount, level and intensity of care demands.[43] Caregivers often take the support of other family members during acute phase in order to deal with the stressful situation of caring mentally ill during symptomatic phase. Similar observation been reported by Given et al.,[43] in their study found that secondary caregivers left the care situation over time and only returned with increased physical care needs. It was found[44] that there were significant changes over time for the carers while their family members with mental illness are in patients treatment, most striking was a reduction in the severity of caring difficulties post treatment phase. Caregivers of people mental illness face different challenges and they are affected by cultural and social attitudes to the illness, and these have important effects on the level of burden experienced. Caregivers do have stress while caring their mentally ill family members, their stress and burdens need to be addressed in the interest of person with mental illness. Caregiving for chronically mentally ill family members disrupts the normal functions of families, and it almost always causes stress in the family. Examining caregiving within the context of stress theory, they have[45] a distinction between primary stressors, caused by performing the work required to care for the sick family members, and secondary stressors, problems that emerge in social roles and relationships as a result of caregiving. This distinction highlights the fact that caregiving work is not only stressful because it requires the performance of difficult physical care and medical care like administering medicines, follow-ups, involvement in productive work and encouraging, but also because of secondary stressors: Marital discord, social isolation, economic strains and family dysfunction.[46]

The caregivers’ needs should be understood and addressed; they have variety of psychosocial needs: Understanding illness, managing the ill family member, dealing with stigma, involving them in to community activities, etc.[4,47,48] There is a need for developing psychosocial interventions for caregivers in order to address their mental health and their needs. Caregivers needs of caring and concerns of caring should be supported in order to enhance the quality of care and to reduce the burden of caring. A study in India carried out to understand the needs of families of those with mentally ill members and the impact of family level interventions at the community level on those families, revealed that the psychosocial problems of families were related to their high level of expectations (of the person with mental illness) and of their emotional (over) involvement.[49] Other problems, from the perspective of both caregivers and patients, lay in the question of patients’ marriages and general rehabilitation into society. The study concluded that ‘family members have multiple needs when living with a person with chronic schizophrenia. The needs should be understood and met to enhance the functioning of the family to provide care and thereby reduce emotional problems of the family members’.[49]

The nature of the relationship between caregiver and the mentally ill person, interpersonal relation within the family, pre-existing emotional resources of the caregiver, type of the family, coping ability of the caregiver, availability of economic and social support personality of the caregiver, caregiving beliefs and values have been found to be significant related to the caregiving.[9,50,51,52] The structure of the family as well as their life stage as a family, e.g., elderly parents caring for an adult with severe mental illness, or a former family breadwinner incapacitated by mental illness will have its effect on the caring. This can also present challenges to caregivers.[53,54]

The recent trends in the community-based intervention have raised many expectations from the family, as they are viewed as primary caregiver of their mentally ill family member. Families are now seen as a principal source of support and an important partner in the rehabilitation of the mentally ill The responsibilities are most often assumed by the immediate family member, carries the heaviest part of the family burden.[9,55,56,57,58] Caregivers who are highly burdened and distressed may have diminished coping resources and exercise less resilience in dealing with crises or exacerbations of the patient's illness.[59] The caregivers should be acknowledged and looked as resource in the mental health programme. The caregivers should be included, consulted and their voices should be recorded while we draft the mental health policy for the country. The national mental health progamme should incorporate caregivers as resources and initiate programme for the enhancing the well being of unheard caregivers.

The present study was conducted in order to understand the caregiving of the families, their role in the recovery of their mentally ill family member. Their contributions to the recovery would never get emphasized nor acknowledged. There is a need for measuring and understanding caregivers roles in the recovery of the person, which is a hidden cost not getting reflected in the cost arrived at treating people with mental illness in their homes and in communities. In India, 0.83% of the total health budget is spent for mental health services[60], does this includes the hidden cost of caregiving, a question to be reflected and answered.

The study addressed a clinically important topic that has rarely been explored in research. The current study has some limitations. The sample was selected in a non random sampling taking all the beneficiaries of the CBR programme. Some of the findings of caregiving giving experience may be confound by the differences seen in the socio cultural background of the area. The duration of illness and the clinical status also determine the caregiving experiences. It included a relatively small number of caregivers when compared to vast prevalence of severe mental illness. The researcher used research as a tool for creating awareness among the field workers and the caregivers about the importance of their role in the recovery of people with mental illness. The aim of research was to empower the caregivers with the information and make them realize the invisible efforts they are investing for their mentally ill family member. The data was collected by the different mental health coordinators using interview schedule after attending the two days of training. The mental health coordinators do not have formal research training, and been involved in data collection of this sort may act as limitation for the present study. The primary caregiver been interviewed for the present study, there are other caregivers in the family who also shares the burden of caring, researchers would have interviewed multiple caregivers and got their understanding of the caregiving process, which would have add value for the present study.

CONCLUSION

To conclude, the present study highlights that caregiving roles will be similar and the experiences also similar for all caregivers of people with schizophrenia, affective disorder and psychosis NOS. There is a significant relationship between the acute phase of the illness and caregivers burden of providing physical care, medical care and psychological care. The social care starts once the person with illness is moving towards the remission phase. Modern medical interventions and technologies that have extended the lives of chronically ill persons have increased the responsibility of families for caring for the sick. Many chronic illnesses like mental illness that once signaled institutionalization can now be managed by CBR and medical interventions, caring people with severe mental illnesses in their homes. The caregiver performs more or less similar caregiving roles and feels it is their responsibility of caring a mentally ill family member, do not like to shift the responsibility on the government. Moreover, the escalating costs of healthcare in most countries has led to restrictions) of institutionalization and encouraging community care and family care as it foster the rehabilitation process.[61] Thus, it is necessary to understand the role of caregiver in the recovery process, adequately acknowledged and recognized, often to be reminded so that they would recognize their roles themselves, would act as motivating for them to continue to care their mentally ill family member. Their exist a need for developing specific intervention package to empower the caregivers, need to see them as resource rather than just recipients of mental health services.

Footnotes

CBR programmes aims at empowering people with disabilities (PWD) in their own communities so that their rights are respected and safeguarded. Basic needs India (BNI) is capacitating NGOs/community-based organizations (CBOs) to include mental health in their existing CBR programme.

BNI is a trust working as a resource group in Mental Health and Development, capacitate NGOs and CBOs to include mental health programme in their existing community development activity. BNI, operate in parts of 8 states in partnership with 50 NGOs in South India, Orrisa, Maharastra, Bihar and Jharkhand.

Sacred is an NGO implementing CBR for people with disability in Ananthpur rural mandal and Papuly rural mandal in Ananthpur and Kurnool district. The community mental health programme been included in their CBR programme.

GASS is an NGO implementing CBR for people with disability in Dodabalapur taluk, Banaglore rural district. The community mental health programme been included in their CBR programme.

Narendra Foundation is a NGO implementing CBR for people with disability in Pavagada taluk, Tumkur district. The community mental health programme been included in their CBR programme.

The mental health co-ordinators are the co-ordinators of the mental health programme, they have attended series of training on mental health issues, rehabilitation and livelihoods. They are trained by the mental health professionals and development practitioners, hand holding support was provided to all the mental health co-ordinator by psychiatric social worker on a monthly basis.

Symptomatic: A person during symptomatic phase exhibits gross dysfunction in physical, psychological and social functioning:

- Physical symptoms: Dramatic changes in eating and sleeping habits, bowel and bladder disturbances, sexual disturbances and many unexplained physical problems.

- Psychological symptoms: Irritability/anger; excessive fear, worry, anxiety and sadness; extreme highs and lows in mood; thought disturbances, confused thinking, delusions, illusions, perceptual abnormalities, memory disturbances, difficulty in concentration and gaining attention and in judging the situations.

- Social symptoms: Social withdrawal, difficulty in maintaining personal hygiene, increasing inability to cope with daily problems and activities.

Remission phase: The indicators for stabilization could be seen at two levels:

Individual level:

- Reduction of symptoms to a large extent and this stage is consistent for not less than 3 months, with or without treatment.

- Attending to self-care, personal hygiene and daily activities.

- Greater understanding of the situation and voluntarily taking the prescribed dose of medication.

- Regaining the insights, judgment, etc.

- Showing interest to participate/to involve in the activities of family and community.

- Beginning to take responsibilities voluntarily and exploring gainful occupations.

Family level:

- Carer gets relieved of the burden and finds time to engage in her/his own work.

- Increased understanding of the illness and its management results in appropriate support to the affected person.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Janardhana N, Shravya R, Naidu DM, Saraswathi L, Seshan V. ‘Caregivers in Community Mental Health’ Basic Needs India. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janardhana N. Stigma and Discrimination experienced by families of mentaly ill- victims of mental illness; Contemporary Social Work. 2011:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spaniol L, Bhakta Parker. Harriet, editor. ‘Coping strategies for Families of people who have mental illness In ‘Helping Families cope with mental illness’. Lefley and Mona Wasow. 2001:131–46. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jagannathan A, Thirthalli J, Hamza A, Hariprasad VR, Nagendra HR, Gangadhar BN. A qualitative study on the needs of caregivers of in patients with schizophrenia in India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57:180–94. doi: 10.1177/0020764009347334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lefley HP, Wasow M. Harriet, editor. ‘Helping families cope with mental illness’. Lefley and Mona Wasow. 1994:131–46. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janardhana NR, Naidu DM, Saraswathy L, Seshan V. ‘Unsung samaritian in the lives of people with mental illness: An Indian Experience’. Indian J Soc Work. 2014;75:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldassano C. Reducing the burden of bipolar disorder for patient and caregiver. Medscape Psychiatry Ment Health. 2014. [Last accessed on 22nd June 2014]. p. 9. Available from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/493650 .

- 8.Chakrabarti S, Raj L, Kulhara P, Avasthi A, Verma SK. Comparison of the extent and pattern of family burden in affective disorders and schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 1995;37:105–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGilloway S, Donnelly M, Mays N. ‘The experience of caring for former long stay psychiatric patients. Br J Clin Psychol. 1997;36:149–51. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollio DE, North CS, Osborne V, Kap N, Foster DA. The impact of psychiatric diagnosis and family system relationship on problems identified by families coping with a mentally ill member. Fam Process. 1990;40:199–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4020100199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roychaudhuri J, Mondal D, Boral A, Bhattacharya D. Family burden among long term psychiatric patients. Indian J Psychiatry. 1995;37:81–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leff J. Working with families of schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1994:71–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bulger MW, Wandersman A, Goldman CR. Burdens and gratifications of caregiving: Appraisal of parental care of adults with schizophrenia. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63:255–65. doi: 10.1037/h0079437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thara R, Padmavati R, Kumar S, Srinivasan L. Instrument to assess burden on caregivers of chronically mentally ill. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:21–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murthy RS. Mental Health by the people, Bangalore: People's Action For Mental Health (PAMH) 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janardhana N, Shravya R, Saraswathy L, Seshan V. ‘Giving care to men and women with mental illness’. Indian J Gender Stud. 2011;18:405–24. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janardhana N, Naidu DM. ‘Inclusion of people with mental illness in community based rehabilitation: Need of the day’. Int J Psychosoc Rehabil. 2012;16:117–24. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shankar R, Menon MS. ‘Interventions with families of people with schizophrenia: The issues facing a community rehabilitation center in India. Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1995;15:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jungbauer J, Angermeyer MC. ‘Living with a schizophrenic patient: A comparative study of burden as it affects parents and spouses. Psychiatry. 2002;65:110–23. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.2.110.19930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stengard E. Caregiving types psychosocial well-being of caregivers of people with mental illness in Finland. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2002;26:154–64. doi: 10.2975/26.2002.154.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song L, Biegel DE, Milligan E. “Predictors of depressive symptomatology among lower social class caregivers of persons with chronic mental illness”. Community Ment Health J. 1997;33:269–86. doi: 10.1023/a:1025090906696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leff J, Vaughn C. New York: Guilford; Expressed emotion in families: Its significance for mental illness. [Google Scholar]

- 23.BNI. Baseline Document on situation of people with mental illness and development programme, South India, Basic Needs India, unpublished data. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 24.BNI. Midterm Evaluation of the Community Mental Health and Development Programme, Basic Needs India, unpublished data. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geneva: 2010. WHO, Guidelines on Community- based rehabilitation for people with mental illness Vol 1-5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murthy RS. Family and mental health care in India Bangalore: People's Action For Mental Health (PAMH) 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 27.New Hope: WHO; 2001. >WHO World Health report, Mental health: New Understanding. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ricard N, Bonin JP, Ezer H. Factors associated with burden in primary caregivers of mentally ill patients. Int J Nurs Stud. 1999;36:73–83. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(98)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murthy RS. Mental Health Care in India, past present and future People's Action For Mental Health (PAMH) 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kulhara P, Wig NN. The chronicity of schizophrenia in North — West India: Results of a follow up study. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132:186–90. doi: 10.1192/bjp.132.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.New Delhi: ICMR; 1988. ICMR (1988) Final report: Multi centered Collaborative study of factors associated with the course and outcome of chronic schizophrenics. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amirkanyan AA, Wolf DA. Caregivers stress and non caregivers stress: Exploring the pathways of psychiatric morbidity. Genontol. 2003;43:817–27. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.6.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Washington, DC: Findings from a national survey & AARP; 1997. Alliance for Caregiving, Family care giving in the U.S. [Google Scholar]

- 34.San Francisco: Author; 2007. Family Caregiver Alliance. Family caregiving: State of the art, future trends. Report from a National Conference. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreisman DE, Joy VD. Family response to the mental illness of a relative: A review of 1974 the literature. Schizophr Bull. 1974;10:34–57. doi: 10.1093/schbul/1.10.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DC: DHHS and DOL; 2003. May, U.S. Department of Health and relation to the Human Services Report to Congress. Washington, U. S. Department of Labor, The future supply of long-term care workers in, aging baby boom generation. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spillman BC, Pezzin LE. Potential and active family caregivers: Changing networks and the “sandwich generation”. Milbank Q. 2000;78:347–74. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chadda RK, Singh TB, Ganguly KK. Caregiver burden and coping: A prospective study of relationship between burden and coping in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:923–30. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nehra R, Chakrabarti S, Kulhara P, Sharma R. Caregiver-coping in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: A re-examination. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:329–36. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0884-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Addington J, Coldham EL, Jones B, Ko T, Addington D. The first episode of psychosis: The experience of relatives. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108:285–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Addington J, McCleery A, Addington D. Three-year outcome of family work in an early psychosis program. Schizophr Res. 2005;79:107–16. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aggarwal M, Avasthi A, Kumar S, Grover S. Experience of caregiving in India: A study from India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57:224–36. doi: 10.1177/0020764009352822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Given CW, Stommel M, Given B, Osuch J, Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC. The influence of the cancer patient's symptoms, functional states on patient's depression and family caregiver's reaction and depression. Health Psychol. 1993;12:277–85. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szmukler E, Kupers J, Joyce T, Harris M, Leese W, Maphosa E. ‘An exploratory randomised controlled trial of a Social support for carers of patients with a psychosis’ psychiatry. Epidemiol. 2008;38:411–8. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0652-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aneshensel CS, Pearlin LI, Schuler RH. ‘Stress, role captivity, and the cessation of caregiving. J Health Soc Behav. 1993;34:54–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shah AJ, Lotoo WJ. ‘Psychological distress in carers of people with mental disorders’, Ovais. Br J Med Pract. 2010:3. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janardhana NN. Community Mental Health and Development model evolved through consulting people with mental illness. In: Murthy RS, editor. Mental health by the people. Bangalore: People's Action For Mental Health (PAMH); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shetty SM. Bangalore, India: Ramakrishna Jayashree Mathew Varghese (1996) Educating the families of patients with schizophrenia: An Evaluative study, Unpublished Ph.d Thesis submitted to NIMHANS. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suman C, Baldev S, Murthy RS, Wig NN. Helping chronic schizophrenics and their families in the community — Initial observations. Indian J Psychiatry. 1980;22:97–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adler LL. “Women and Gender Roles.”. In: Adler LL, Gielen UP, editors. Cross-Cultural Topics in Psychology. Westport: Praeger; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Songwathana P. “Women and AIDS caregiving: Women's work?”. Health Care for Women Int. 2001;22:263–79. doi: 10.1080/073993301300357197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yates ME, Tennstedt S, Chang BH. “Contributors to and mediators of psychological well-being for informal caregivers”. Psychol Soc Sci. 1999;54B:P12–22. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.1.p12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pot AM, Deeg DJ, Knipscheer CP. “Institutionalization of demented elderly: The role of caregiver characteristics”. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;6:273–80. doi: 10.1002/gps.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tarrier N. Some aspects of family interventions in schizophrenics: 1. Adherence to intervention programme. (483-4).Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:475–80. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cook JA. Who ‘mothers’ the chronically mentally ill. Fam Relat. 1988;37:42–9. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chafetz L, Barnes L. ‘Issues in psychiatric caregiving’. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1989;3:61–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coward RT, Dwyer JW. ‘The association of gender sibling network composition and patterns of care by adult children’. Res Aging. 1990;12:158–81. doi: 10.1177/0164027590122002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.St Onge M, Lavoie F. The experience of caregiving among mothers of adults suffering from psychotic disorders: Factors associated with their psychological distress. Am J Community Psychol. 1997;25:73–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1024697808899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Noh S, Avison WH. Spouses of discharged psychiatric patients: Factors associated with their experience of burden. J Marriage Fam. 1988;1:377–89. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. World Health Organization Atlas: Country profiles on mental health resources. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Janardhana N, Shravya R, Naidu DM, Hampanna Availability and accessibility of treatment for persons with mental illness through community mental health programme. Disability, CBRE and Inclusive Development. 2011;22:124–33. [Google Scholar]