Abstract

Rationale: In cystic fibrosis (CF), pulmonary exacerbations present an opportunity to define the effect of antibiotic therapy on systemic measures of inflammation.

Objectives: Investigate whether plasma inflammatory proteins demonstrate and predict a clinical response to antibiotic therapy and determine which proteins are associated with measures of clinical improvement.

Methods: In this multicenter study, a panel of 15 plasma proteins was measured at the onset and end of treatment for pulmonary exacerbation and at a clinically stable visit in patients with CF who were 10 years of age or older.

Measurements and Main Results: Significant reductions in 10 plasma proteins were observed in 103 patients who had paired blood collections during antibiotic treatment for pulmonary exacerbations. Plasma C-reactive protein, serum amyloid A, calprotectin, and neutrophil elastase antiprotease complexes correlated most strongly with clinical measures at exacerbation onset. Reductions in C-reactive protein, serum amyloid A, IL-1ra, and haptoglobin were most associated with improvements in lung function with antibiotic therapy. Having higher IL-6, IL-8, and α1-antitrypsin (α1AT) levels at exacerbation onset were associated with an increased risk of being a nonresponder (i.e., failing to recover to baseline FEV1). Baseline IL-8, neutrophil elastase antiprotease complexes, and α1AT along with changes in several plasma proteins with antibiotic treatment, in combination with FEV1 at exacerbation onset, were predictive of being a treatment responder.

Conclusions: Circulating inflammatory proteins demonstrate and predict a response to treatment of CF pulmonary exacerbations. A systemic biomarker panel could speed up drug discovery, leading to a quicker, more efficient drug development process for the CF community.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, pulmonary exacerbation, inflammation, plasma, biomarker

Clinical and translational research in cystic fibrosis (CF) is hampered, in part, by a lack of sensitive biochemical measures of treatment response. As a result of a growing pipeline of drugs, including treatments targeting the basic protein defect, which have led to improved lung function, reduced frequency of pulmonary exacerbations, and increased life expectancy (1, 2), it is becoming more difficult to demonstrate efficacy with investigational therapies in CF. The CF community has recognized this challenge and emphasized the need to identify and validate biomarkers to serve as prognostic indicators of therapeutic response and outcome measures in early-phase CF clinical trials (3). Because lung disease is the major determinant of quality of life and survival in CF, and airway inflammation is a hallmark feature of CF lung disease, there is strong rationale to focus the search for relevant pulmonary biomarkers to measures of inflammation.

Acute pulmonary exacerbations are episodes of acute worsening of respiratory symptoms (4). Intravenous antibiotics are prescribed to those individuals judged to have severe symptoms and those who fail to adequately respond to outpatient oral and nebulized antibiotic therapy. Numerous studies have demonstrated that patients with CF generally improve within 2 weeks of being started on intravenous antibiotics (5). Therefore, exacerbations present a unique opportunity to define the effect of intravenous antibiotic therapy on candidate markers of inflammation and to determine whether clinical improvements are associated with significant and relatively rapid changes in inflammation.

Systemic (blood-based) markers of inflammation are ideal in that blood measurements are easily standardized, repeatable, and can be obtained from subjects of any age and disease severity. An important question however, is whether systemic markers are sensitive enough to detect a meaningful change in lung disease, given that the inflammatory response to infection in CF is largely confined to the lung (6). A recent systematic review summarized the results of studies that have used systemic biomarkers to monitor response to treatment during pulmonary exacerbations (7). C-reactive protein (CRP) has been the most widely investigated biomarker, decreasing in response to exacerbation treatment in the majority of studies. Other promising candidate biomarkers include neutrophil elastase antiprotease complexes (NEAPC), IL-6, and calprotectin. As noted in the review (7), most of these studies were small, single-center studies that enrolled primarily adults with CF and relied on varying definitions of pulmonary exacerbations. Additionally, none of these studies investigated a panel of blood biomarkers to monitor response to exacerbation treatment or examined whether blood biomarkers can predict which individuals fail to recover to their baseline lung function (7).

In this prospective, multicenter study, we measured changes in 15 plasma proteins during intravenous antibiotic treatment for pulmonary exacerbations and at a follow-up visit to (1) investigate relationships between systemic inflammation and indicators of clinical improvement, (2) determine whether systemic measures of inflammation can reliably distinguish exacerbation from stable disease, and (3) examine the value of a systemic inflammatory panel for predicting clinical response to intravenous antibiotic therapy. This is the largest and most comprehensive study of plasma measures of inflammation during CF exacerbations ever reported. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in abstract form (8).

Methods

Study Subjects and Design

Patients with CF 10 years of age and older who were being treated with intravenous antibiotics for a pulmonary exacerbation were recruited from six accredited CF Foundation (CFF) care centers. Participants had to demonstrate at least 3 of 11 criteria for pulmonary exacerbation, defined by a CFF consensus committee (see Table E1 in the online supplement) (9). An exacerbation score was calculated for each subject at the time of antibiotic initiation using a previously published scoring system (10). Participants were treated with at least two intravenous antibiotics, targeting their specific CF pathogens, and aggressive mucus clearance based on standard CF clinical care guidelines (9) for a minimum of 10 days. Concomitant administration of inhaled and oral antibiotics and systemic corticosteroids were left to the discretion of the treating physicians at the participating sites (indications for corticosteroid treatment are provided in the online supplement). Blood was first collected within 24 hours of starting intravenous antibiotic therapy (Visit 1). Attempts were made to collect these samples before the administration of the first dose of intravenous antibiotics; however, the administration of antibiotics was not considered an exclusion criterion.

The second blood specimens were obtained toward the end of the treatment course, typically between Days 10 to 21 after starting intravenous antibiotics (Visit 2), and the third blood specimens were collected at a routine outpatient clinic visit at least 2 weeks after completing all systemic antibiotic treatment (intravenous and oral) for their pulmonary exacerbation (Visit 3). At all three time points, anthropometric data and oxygen saturations were obtained, sputum was collected for microbiology per CF consensus guidelines (11), and spirometry was performed. Spirometric values included FVC and FEV1 and were expressed as percent of predicted normal using reference equations (12, 13). Participants were withdrawn from analyses if blood was not collected and properly processed at the first two time points (Visits 1 and 2). This study had approval from the local research ethics committee of each participating institution, and all participants or guardians provided written informed consent.

Blood Processing and Analysis of Plasma Proteins

Venous blood was collected into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid collection tubes and processed and stored according to a standard operating procedure developed specifically for this study (details provided in the online supplement). Plasma proteins were measured in the CFF Therapeutics Center for Biochemical Markers at the University of Colorado. A list of the commercially available assays used to measure each of the 15 plasma analytes is provided in Table E2. An aliquot of serum was also collected at each time point and submitted to the onsite hematology laboratory for a complete blood count and cell differential counts.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported for baseline and change measures; two-sided P values for analyte changes were derived from paired t tests. Spearman correlation coefficient was used to assess correlations between plasma markers and clinical measures. A “responder” to antibiotic therapy was someone who recovered to baseline lung function defined as any FEV1 in the 3 months after intravenous antibiotic treatment that was greater than or equal to 90% of the best FEV1 within 6 months before the exacerbation (14). Multivariate modeling (three staged, step-down, significance threshold = 0.10) and area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC) and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for unnested models were used to identify a panel of plasma analytes (both baseline and change measurements) that were predictive of being a responder. Additional details are provided in the online supplement.

Results

Baseline Patient Characteristics and Clinical Response to Antibiotic Therapy

One hundred twenty-three participants were enrolled; 122 completed the first blood collection, 103 completed the first and second collections, and 70 completed all three collections (Figure E1). Baseline clinical characteristics of the 103 who had paired blood collections during intravenous antibiotic treatment for exacerbations are summarized in Table 1. Ninety-eight (95%) study participants had a pulmonary exacerbation score of 2.6 or higher (mean ± SD, 4.4 ± 1.4; range, 1.5–8.7). Fifty-two percent of participants experienced a decrease in FEV1 of at least 10% from a previous measurement taken within 3 months before their exacerbation. Duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy was 16.8 ± 7.9 days (range, 7–61 d), and the time between the first two blood collections was 14.8 ± 4.8 days (range, 6–31 d). The third visit occurred 292 ± 140 days (range, 35–659 d) after completing treatment for the exacerbation. The most common intravenous antibiotic treatments prescribed for the exacerbations were tobramycin (66% of participants), meropenem (50%), ceftazidime (27%), and vancomycin (25%). Seventeen percent of participants were also treated with systemic corticosteroids. All clinical measurements, including FEV1, FVC, oxygen saturations, weight, and body mass index (BMI) significantly improved after antibiotic therapy (Table E3).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with paired blood collections during intravenous antibiotic treatment for pulmonary exacerbations at exacerbation onset

| N = 103 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 23.5 | 9.9 |

| Age group | ||

| 10–18 yr, n (%) | 32 | 31.1% |

| Mean (SD) | 13.5 | 2.4 |

| >18 yr, n (%) | 71 | 68.9% |

| Mean (SD) | 28.1 | 8.6 |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 64 | 62.1% |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 96 | 93.2% |

| Hispanic | 3 | 2.9% |

| African American | 3 | 2.9% |

| Aleut/Eskimo | 1 | 1.0% |

| Genotype n (%) | ||

| F508del homozygous | 58 | 56.3% |

| F508del heterozygous | 38 | 36.9% |

| Unknown | 7 | 6.8% |

| Pancreatic insufficient, n (%) | 97 | 94.9% |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 20.1 | 3.3 |

| FEV1, mean (SD), L | 1.7 | 0.7 |

| FEV1% predicted,* mean (SD) | 54.7 | 21.3 |

| FEV1% predicted group,* n (%) | ||

| <50% | 51 | 49.5% |

| 50–70% | 25 | 24.3% |

| 70–90% | 21 | 20.4% |

| FVC, mean (SD), L | 2.7 | 0.9 |

| FVC % predicted,* mean (SD) | 71.4 | 18.5% |

| Microbiology,† n (%) | ||

| No growth | 1 | 1.1% |

| Growth observed | 88 | 98.9% |

| Polymicrobial cultures | 65 | 73.0% |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa: any | 67 | 75.3% |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mucoid | 53 | 59.6% |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa: nonmucoid | 32 | 36.0% |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 30 | 33.7% |

Spirometry % predicted is calculated using the Wang equations (12) for female subjects less than 16 yr of age and male subjects less than 18 yr of age. The Hankinson equations (13) are used for female subjects 16 yr and older and male subjects 18 yr and older.

Baseline respiratory culture data were available from 89 participants.

Relationships between Systemic Inflammation and Patient Characteristics at Exacerbation Onset

Baseline differences in plasma protein measurements and serum white blood cell (WBC) and neutrophil counts at the onset of exacerbations (V1) were examined by age (< vs. ≥18 yr of age), FEV1 (< vs. ≥70% predicted), Pseudomonas aeruginosa and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection status, and steroid use during exacerbation treatment. Older participants with CF had significantly higher baseline circulating WBC and neutrophil counts and concentrations of high sensitivity (hs)CRP, serum amyloid A (SAA), ceruloplasmin, haptoglobin, granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), and α1-antitrypsin (α1AT) compared with younger participants, whereas transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and soluble (s)CD40 levels were significantly higher among younger participants with CF (Table E4). Those with lower FEV1 at the time of exacerbation had significantly higher WBC and neutrophil counts and higher concentrations of 10 of the 15 plasma proteins compared with those with higher FEV1 (Table E5). There were no differences in any of the systemic measures of inflammation at baseline by P. aeruginosa (Table E6) or MRSA (Table E7) status. Study participants treated with a course of systemic corticosteroids during their exacerbation had lower baseline tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α concentrations compared with the majority not treated with steroids (Table E8). There were no observed associations between baseline measures of systemic inflammation and pulmonary exacerbation score or mean decline in FEV1% predicted at exacerbation onset (assessed by best FEV1 within 6 mo of the exacerbation and FEV1 at V1) (data not shown).

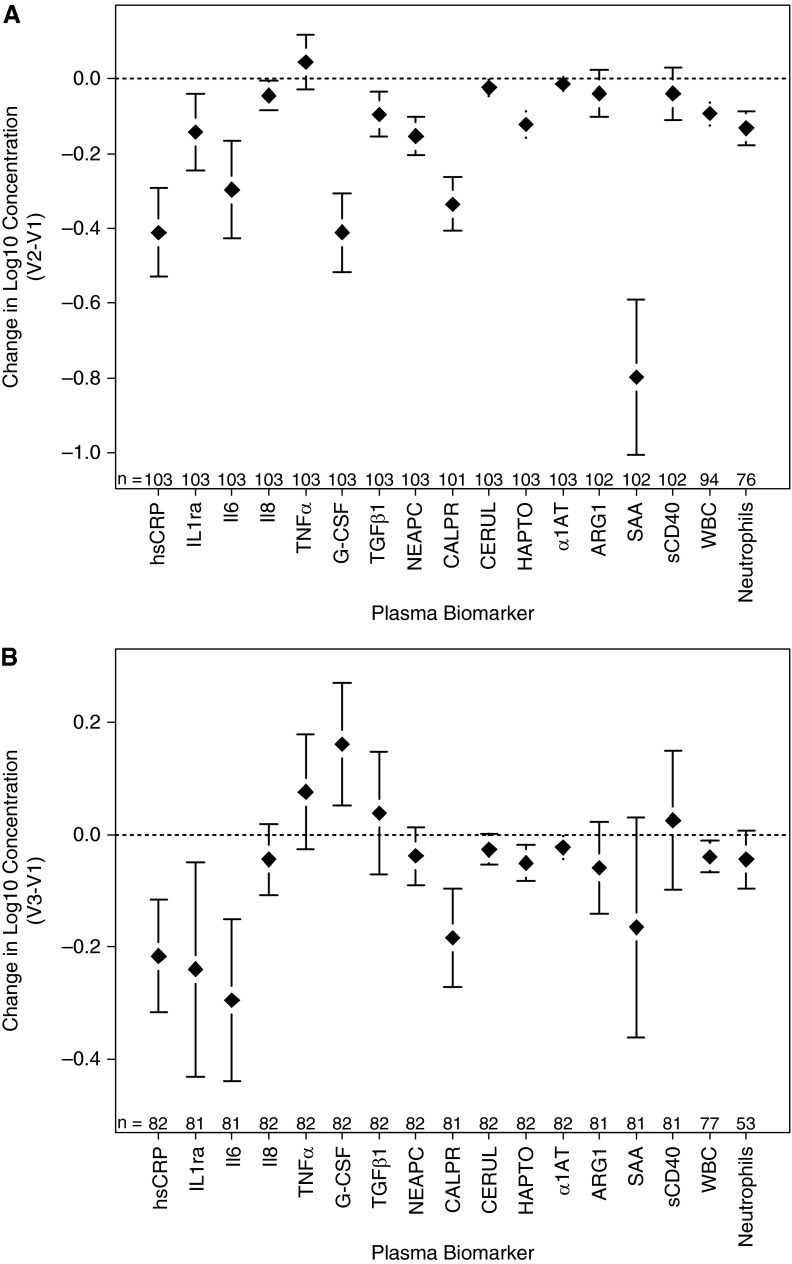

Change in Systemic Inflammation during Exacerbations and on Return to Clinical Stability

Concentrations of the 15 plasma proteins, serum WBC, and neutrophil counts at baseline, after intravenous antibiotic therapy (V2), and at a clinically stable visit (V3) are reported in Table 2. Significant reductions in several markers of systemic inflammation were observed during intravenous antibiotic treatment for exacerbations: hsCRP, IL-1ra, IL-6, G-CSF, TGF-β1, NEAPC, calprotectin, ceruloplasmin, haptoglobin, SAA, WBC, and neutrophil counts (Figure 1A). Greater reductions in hsCRP and IL-8 were seen in the participants treated with concomitant systemic corticosteroids versus those who were not (Table E9). Changes in systemic measures of inflammation based on underlying infection status are presented in Tables E10 (P. aeruginosa) and E11 (MRSA). Significant differences were also observed between clinical stability (V3) and exacerbation (V1) for hsCRP, IL-1ra, IL-6, calprotectin, ceruloplasmin, haptoglobin, SAA, and WBC (all decreased at V3) and G-CSF (increased at V3) (Figure 1B).

Table 2.

Plasma protein concentrations and serum white cell and neutrophil counts (log10 transformed values) at exacerbation onset (V1), end of antibiotic therapy (V2), and a clinically stable follow-up visit (V3)

| Analyte | Preintravenous (V1) |

End of Therapy (V2) |

Clinical Stability (V3) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |

| hsCRP | 122 | 0.94 | 0.58 | 103 | 0.56 | 0.41 | 82 | 0.74 | 0.49 |

| IL-1ra | 122 | 0.87 | 0.57 | 103 | 0.76 | 0.64 | 81 | 0.64 | 0.69 |

| IL-6 | 121 | 1.01 | 0.70 | 103 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 82 | 0.72 | 0.51 |

| IL-8 | 122 | 1.06 | 0.26 | 103 | 1.01 | 0.32 | 82 | 1.01 | 0.30 |

| TNF-α | 122 | 0.73 | 0.39 | 103 | 0.77 | 0.36 | 82 | 0.78 | 0.29 |

| G-CSF | 122 | 1.62 | 0.56 | 103 | 1.23 | 0.54 | 82 | 1.78 | 0.42 |

| TGF-β1 | 122 | 3.89 | 0.42 | 103 | 3.79 | 0.38 | 82 | 3.97 | 0.30 |

| NEAPC | 122 | 1.94 | 0.26 | 103 | 1.81 | 0.18 | 82 | 1.89 | 0.23 |

| CALPR | 122 | 0.81 | 0.44 | 101 | 0.50 | 0.27 | 81 | 0.64 | 0.36 |

| CERUL | 122 | 1.57 | 0.13 | 103 | 1.56 | 0.15 | 82 | 1.55 | 0.12 |

| HAPTO | 122 | 2.28 | 0.20 | 103 | 2.16 | 0.24 | 82 | 2.23 | 0.19 |

| α1AT | 122 | 2.26 | 0.10 | 103 | 2.26 | 0.09 | 82 | 2.24 | 0.10 |

| ARG1 | 122 | 1.44 | 0.31 | 102 | 1.42 | 0.29 | 81 | 1.38 | 0.30 |

| SAA | 122 | 4.85 | 1.04 | 102 | 4.07 | 0.83 | 81 | 4.69 | 0.98 |

| sCD40 | 122 | 3.41 | 0.53 | 102 | 3.34 | 0.50 | 81 | 3.46 | 0.44 |

| WBC (103/μl) | 122 | 1.07 | 0.14 | 102 | 0.97 | 0.14 | 79 | 1.04 | 0.14 |

| PMNs (103/μl) | 96 | 0.94 | 0.17 | 81 | 0.80 | 0.18 | 59 | 0.91 | 0.19 |

Definition of abbreviations: α1AT = α1-antitrypsin; ARG1 = arginase-1; CALPR = calprotectin; CERUL = ceruloplasmin; G-CSF = granulocyte colony stimulating factor; HAPTO = haptoglobin; hsCRP = high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; NEAPC = neutrophil elastase antiprotease complexes; PMNs = neutrophils; SAA = serum amyloid A; sCD40 = soluble CD40; TGF-β1 = transforming growth factor-β1; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α; WBC = white blood cell.

Figure 1.

Changes in plasma measures of inflammation (log10 transformed values) (A) with antibiotic therapy (end of antibiotic therapy [V2] − exacerbation onset [V1]), and (B) between exacerbation and clinical stability (clinically stable follow-up visit [V3] − V1). Means and 95% confidence intervals displayed. α1AT = α1-antitrypsin; ARG1 = arginase-1; CALPR = calprotectin; CERUL = ceruloplasmin; G-CSF = granulocyte colony stimulating factor; HAPTO = haptoglobin; hsCRP = high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; NEAPC = neutrophil elastase antiprotease complexes; SAA = serum amyloid A; sCD40 = soluble CD40; TGFβ1 = transforming growth factor-β1; TNFα = tumor necrosis factor-α; WBC = white blood cell.

Relationships between Systemic Inflammation and Clinical Outcomes at Exacerbation Onset and after Antibiotic Therapy

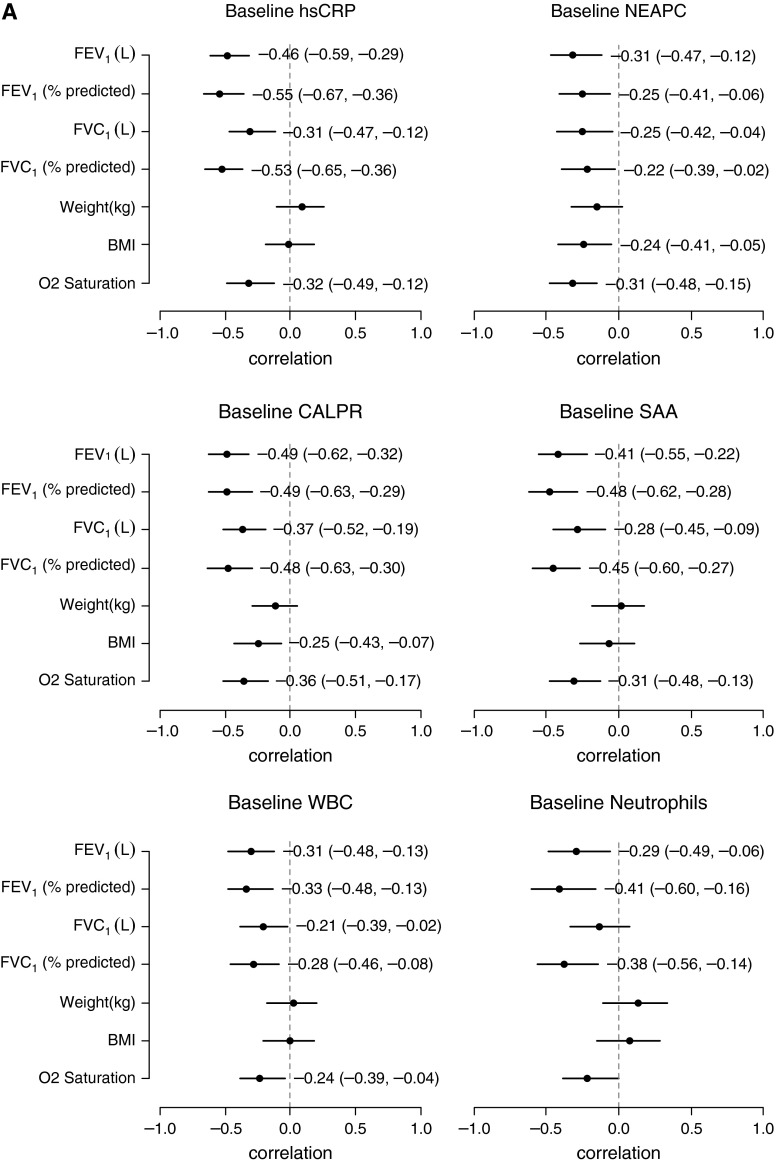

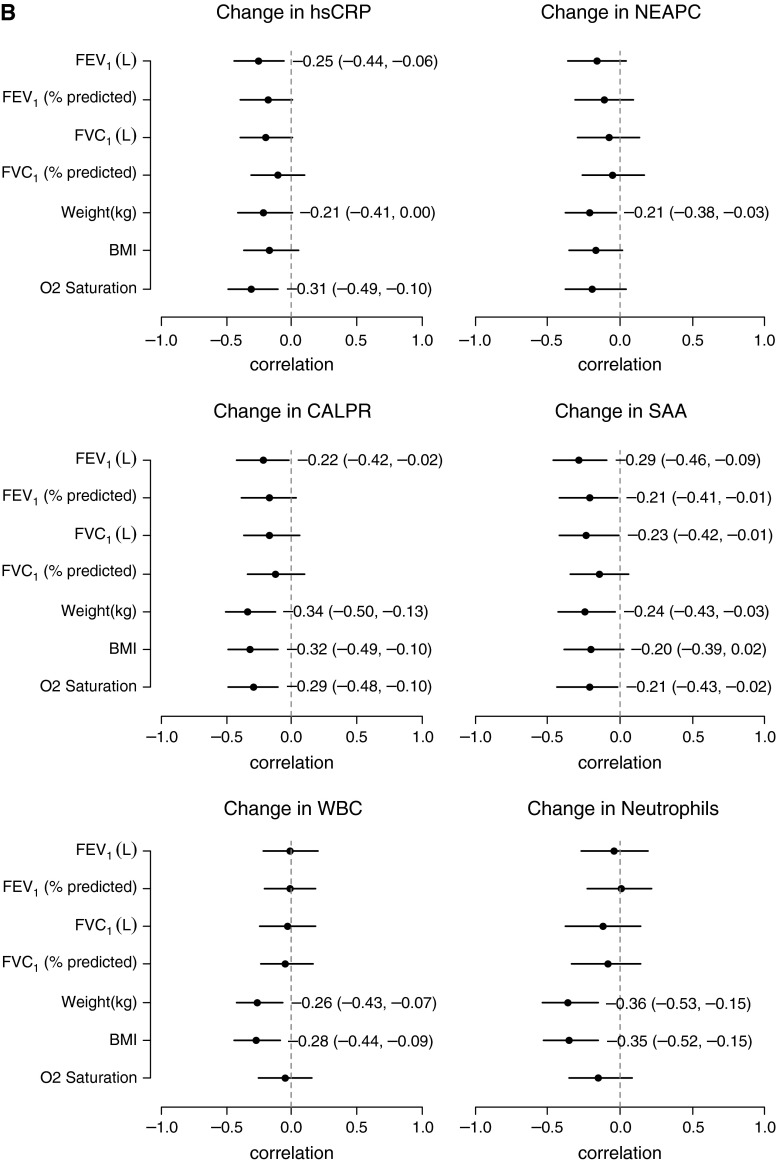

Investigating the relationships between the systemic measurements of inflammation and the clinical measures at the time of exacerbation (V1), there were multiple inverse correlations observed (Table E12). Four of the protein analytes that correlated most strongly with clinical measures at baseline, hsCRP, SAA, calprotectin, and NEAPC, are displayed in Figure 2A. Correlations between changes in inflammatory markers and changes in clinical measures after intravenous antibiotic therapy (V2 − V1) are shown in Table E13. Decreases in calprotectin, α1AT, WBC, and neutrophil counts were most strongly associated with improvements in weight and BMI, whereas reductions in hsCRP, SAA, IL-1ra, and haptoglobin were most associated with improvements in lung function. Correlation plots for changes in select inflammatory markers with changes in clinical measures are presented in Figure 2B. Similar analyses were performed excluding those participants who received corticosteroids during their exacerbation management, and results are displayed in Table E14 and Figure E2.

Figure 2.

Forest plots of correlations at onset of exacerbation (A) and with antibiotic therapy (B) between select markers of inflammation and clinical measures. The correlation coefficients and 95% confidence intervals are displayed; correlations are significant if the confidence interval does not cross zero. BMI = body mass index; CALPR = calprotectin; hsCRP = high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; NEAPC = neutrophil elastase antiprotease complexes; SAA = serum amyloid A; WBC = white blood cell.

Systemic Inflammation and Responder Status

Responder status could be determined in the majority of participants (90/103), and 76 participants (84%) recovered at least 90% of their baseline FEV1 within 3 months of the exacerbation (“responders”). For responders, the mean (SD) FEV1 at exacerbation onset was higher (58.2 [21.4] % predicted) than for nonresponders (44.6 [17.2] % predicted; P = 0.028). No other characteristic, including sex, age, BMI, genotype, exacerbation score, presenting FEV1 drop of 10% or more, intravenous antibiotic duration, or underlying bacterial infection, was significantly associated with responder status. We investigated whether baseline measures of systemic inflammation and changes in these measures were able to discriminate treatment responders from nonresponders (Table 3). Having higher IL-6, IL-8, and α1AT concentrations at the time of exacerbation were associated with an increased risk of being a nonresponder (i.e., failing to recover to baseline FEV1). With antibiotic treatment, only a change in arginase-1 differed significantly by responder status.

Table 3.

Plasma protein concentrations and serum white cell and neutrophil counts (log10 transformed values) at exacerbation onset (V1), and changes in measures of inflammation with antibiotic therapy by responder and nonresponder status

| 90% Recovery to Baseline FEV1 |

P Value* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonresponders (N = 14) |

Responders (N = 76) |

||||||

| N | Mean or (%) | SD | N | Mean or % | SD | ||

| hsCRP at V1 | 14 | 1.14 | 0.59 | 76 | 0.91 | 0.58 | 0.177 |

| IL-1ra at V1 | 14 | 1.09 | 1.01 | 76 | 0.88 | 0.47 | 0.454 |

| IL-6 at V1 | 14 | 1.44 | 0.91 | 76 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 0.025 |

| IL-8 at V1 | 14 | 1.22 | 0.31 | 76 | 1.03 | 0.25 | 0.013 |

| TNF-α at V1 | 14 | 0.88 | 0.59 | 76 | 0.7 | 0.36 | 0.297 |

| G-CSF at V1 | 14 | 1.87 | 0.78 | 76 | 1.58 | 0.52 | 0.196 |

| TGF-β1 at V1 | 14 | 4.11 | 0.5 | 76 | 3.9 | 0.38 | 0.076 |

| NEAPC at V1 | 14 | 2.13 | 0.4 | 76 | 1.93 | 0.23 | 0.095 |

| CALPR at V1 | 14 | 0.97 | 0.44 | 76 | 0.79 | 0.43 | 0.168 |

| CERUL at V1 | 14 | 1.65 | 0.18 | 76 | 1.57 | 0.12 | 0.147 |

| HAPTO at V1 | 14 | 2.32 | 0.19 | 76 | 2.26 | 0.2 | 0.320 |

| α1AT at V1 | 14 | 2.32 | 0.11 | 76 | 2.26 | 0.1 | 0.040 |

| ARG1 at V1 | 14 | 1.48 | 0.37 | 76 | 1.46 | 0.3 | 0.857 |

| SAA at V1 | 14 | 5.08 | 1.09 | 76 | 4.79 | 1.02 | 0.340 |

| sCD40 at V1 | 14 | 3.64 | 0.53 | 76 | 3.38 | 0.54 | 0.103 |

| WBC at V1, 103/μl | 13 | 1.08 | 0.10 | 76 | 1.06 | 0.15 | 0.890 |

| Neutrophils at V1, 103/μl | 10 | 0.95 | 0.12 | 59 | 0.93 | 0.18 | 0.925 |

| hsCRP change† | 14 | −0.31 | 0.67 | 76 | −0.4 | 0.57 | 0.616 |

| IL-1ra change† | 14 | −0.28 | 0.72 | 76 | −0.11 | 0.46 | 0.419 |

| IL-6 change† | 14 | −0.5 | 0.84 | 76 | −0.24 | 0.64 | 0.176 |

| IL-8 change† | 14 | −0.01 | 0.29 | 76 | −0.05 | 0.16 | 0.569 |

| TNF-α change† | 14 | −0.17 | 0.56 | 76 | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.126 |

| G-CSF change† | 14 | −0.5 | 0.48 | 76 | −0.38 | 0.57 | 0.444 |

| TGF-β1 change† | 14 | −0.08 | 0.45 | 76 | −0.11 | 0.28 | 0.820 |

| NEAPC change† | 14 | −0.24 | 0.4 | 76 | −0.12 | 0.21 | 0.292 |

| CALPR change† | 14 | −0.31 | 0.38 | 74 | −0.33 | 0.35 | 0.828 |

| CERUL change† | 14 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 76 | −0.02 | 0.11 | 0.768 |

| HAPTO change† | 14 | −0.04 | 0.14 | 76 | −0.13 | 0.19 | 0.097 |

| α1AT change† | 14 | −0.02 | 0.1 | 76 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.714 |

| ARG1 change† | 14 | −0.2 | 0.34 | 75 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.028 |

| SAA change† | 14 | −0.52 | 1.12 | 75 | −0.82 | 0.96 | 0.308 |

| sCD40 change† | 14 | −0.09 | 0.32 | 75 | −0.03 | 0.38 | 0.552 |

| WBC change† | 12 | −0.08 | 0.15 | 69 | −0.09 | 0.14 | 0.591 |

| Neutrophils change†, 103/μl | 9 | −0.15 | 0.14 | 54 | −0.12 | 0.20 | 0.758 |

Definition of abbreviations: α1AT = α1-antitrypsin; ARG1 = arginase-1; CALPR = calprotectin; CERUL = ceruloplasmin; G-CSF = granulocyte colony stimulating factor; HAPTO = haptoglobin; hsCRP = high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; NEAPC = neutrophil elastase antiprotease complexes; SAA = serum amyloid A; sCD40 = soluble CD40; TGF-β1 = transforming growth factor-β1; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α; WBC = white blood cell.

P value for continuous variables based on two sample t test with pooled or Satterthwaite variance. P value for categorical variables based on the Fisher exact test.

Change is the difference between V2 and V1 in each marker.

Statistically significant P values are presented in bold type.

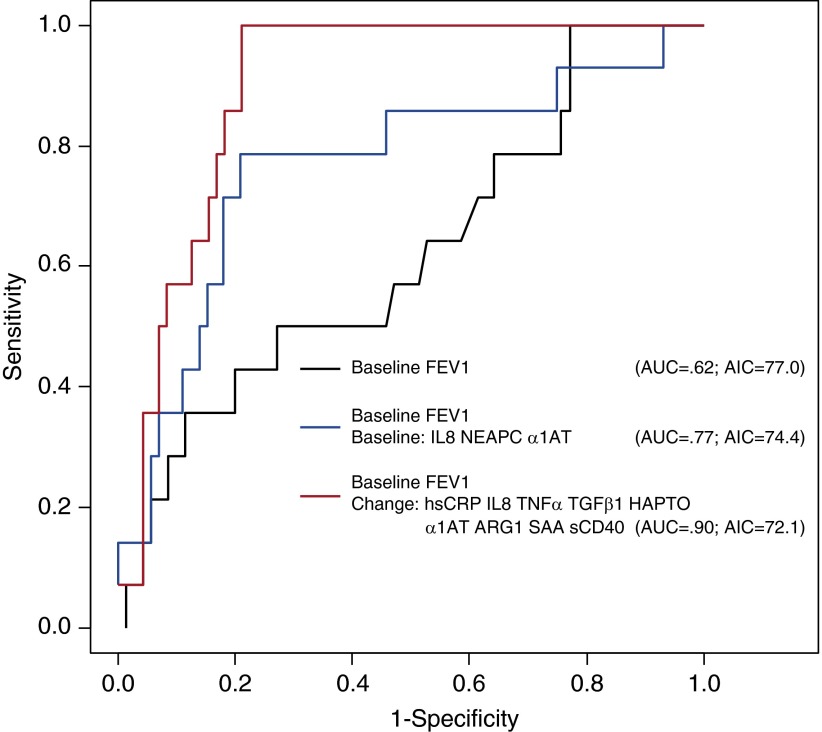

Combining Systemic Inflammation with Clinical Parameters to Predict Responder Status

Considering first the participant and clinical characteristics in a multivariate logistic regression model, only FEV1 at exacerbation onset was predictive of being a responder, with an AUC of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.47–0.79; AIC = 77.0) (Figure 3). Next, adding the systemic measures of inflammation at exacerbation onset, IL-8, NEAPC, and α1AT improved the model, with an AUC of 0.77 (95% CI, 0.65–0.94; AIC = 74.4). Furthermore, changes in hsCRP, SAA, arginase-1, haptoglobin, IL-8, TGF-β1, TNF-α, α1AT, and sCD40 with antibiotic treatment, in combination with FEV1 at exacerbation onset, were more strongly associated with being a responder, with an AUC of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.86–1.0; AIC = 72.1), significantly improved discrimination over FEV1 alone (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curves to predict responder status using baseline FEV1 alone, a combination of systemic inflammatory measurements at exacerbation onset, and changes in inflammatory measurements with antibiotic therapy. AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; α1AT = α1-antitrypsin; ARG1 = arginase-1; AUC = area under the receiver operating characteristics curve; HAPTO = haptoglobin; hsCRP = high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; NEAPC = neutrophil elastase antiprotease complexes; SAA = serum amyloid A; sCD40 = soluble CD40; TGFβ1 = transforming growth factor-β1; TNFα = tumor necrosis factor-α.

Discussion

This multicenter study has demonstrated that several systemic measures of inflammation were responsive to intravenous antibiotic treatment for pulmonary exacerbations and were able to reliably distinguish exacerbation from stable disease. Plasma hsCRP, SAA, calprotectin, and NEAPC correlated most strongly with clinical measures at exacerbation onset. At the time of exacerbation, circulating WBC and neutrophil counts and concentrations of hsCRP, SAA, G-CSF, ceruloplasmin, haptoglobin, and α1AT were significantly higher in older patients with CF and those with lower lung function. After antibiotic therapy, reductions in hsCRP, SAA, IL-1ra, and haptoglobin were most strongly associated with improvements in lung function, whereas decreases in calprotectin, α1AT, WBC, and neutrophil counts correlated with improvements in weight and BMI. This study also sought to determine whether systemic inflammatory proteins were associated with and might even predict which patients fail to recover to their baseline lung function. Among several clinical characteristics considered, FEV1 at exacerbation onset was the only factor associated with responder status (responders were more likely to have a higher FEV1 at exacerbation onset). We found that having higher IL-6, IL-8, and α1AT levels at exacerbation onset were associated with an increased risk of being a nonresponder. Importantly, changes in several inflammatory markers with antibiotic treatment, in combination with FEV1 at exacerbation onset, were more strongly associated with being a responder than FEV1 alone.

Concomitant systemic corticosteroids did not substantially impact the majority of plasma protein measurements, consistent with previous findings that adding oral prednisone to standard CF exacerbation treatment resulted in no significant change in clinical outcomes and no additional reductions in sputum markers of inflammation (15). In our study, though, systemic corticosteroids did lead to greater reductions in hsCRP and IL-8, an effect that has been observed in other acute proinflammatory states treated with corticosteroids (16–18). For the most part, participants treated with corticosteroids during exacerbation were not characterized by distinct biomarker profiles at the onset of exacerbation compared with those who were not treated.

Our findings largely mirror those found in smaller, single-center studies (summarized in Reference 7) demonstrating significant decreases in systemic measures of inflammation after antibiotic treatment during exacerbations. As noted in that review, CRP has been the most widely studied circulating biomarker. Here, we confirm that CRP is highly responsive to exacerbation treatment. Additionally, SAA, calprotectin, and G-CSF demonstrate comparable change with antibiotic treatment. Although CRP and SAA are nonspecific acute-phase reactants, calprotectin and G-CSF are markers of neutrophilic inflammation that might be more informative in tracking disease activity and response to therapy in CF. Circulating calprotectin has shown greater change than other systemic or sputum markers of inflammation with exacerbation treatment (19, 20). Interestingly, G-CSF was the only protein that was higher at the clinically stable follow-up visit than at exacerbation onset. This is an important and potentially worrisome finding, as G-CSF has been implicated in the altered Th1/Th2 lymphocyte profile observed in CF, skewing in the direction of a Th2-dominated immune response in chronically P. aeruginosa–infected patients (21–23). Because we performed complete blood counts, we were able to identify several proteins that were more responsive to exacerbation treatment than circulating WBC and neutrophil counts, including proteins that correlated more strongly with clinical outcomes (lung function and weight improvements) than did WBC and neutrophil counts.

The proteins assayed in this study were identified by an expert panel in a CFF Therapeutics–sponsored CF Proteomics Biomarker Meeting. Selection criteria for the 15 candidate proteins included detection in blood, biologic plausibility, publications suggesting a role for these proteins in CF or other chronic inflammatory lung diseases (including proteomic investigations [24–26]), and availability and subsequent validation of commercial assays (ELISA or other) for these proteins. Although airway inflammation has long been recognized as a hallmark feature of CF lung disease, the role of systemic inflammation in CF has been less clear. Systemic inflammation likely reflects and possibly links the pulmonary component and the extrapulmonary comorbidities of CF, including CF-related diabetes, liver disease, intestinal disease, and bone disease. Even without a clear understanding of what organs or disease processes are principally represented, systemic inflammation may be a specific therapeutic target in patients with CF. In fact, based on preliminary findings from this study, serum CRP, SAA, and calprotectin were measured and used to demonstrate immunomodulatory effects of azithromycin in a CF interventional trial (27). Reduction in these inflammatory markers correlated with improvements in lung function and weight gain, providing indirect evidence that these changes were associated with clinically meaningful outcomes. This was the first study to demonstrate the usefulness of a panel of systemic inflammatory markers in a CF interventional trial, and these data provide evidence that systemic measures of inflammation have added value and should be included in future CF clinical trials.

There is considerable interest to identify and validate biomarkers that aid in the diagnosis of exacerbations, help to define exacerbation severity and etiology, and reflect improvement with exacerbation treatment. In terms of diagnosis, systemic markers of inflammation were not used to diagnose exacerbations in this study, but several were able to distinguish exacerbation from stable disease. We did not observe any relationships between plasma inflammatory proteins and exacerbation severity, and this may reflect the heterogeneity of exacerbations in CF. In fact, there is ongoing debate on how CF pulmonary exacerbations should be defined (28, 29). In practical terms, an exacerbation represents an acute deterioration in symptoms beyond the patient’s usual day-to-day variation. However, this definition entails subjective assessment by both the patient and provider, and there is a need in both the clinic and in clinical trials for an objective method of confirming an exacerbation. Several inflammatory proteins assayed in this study may be useful in this regard.

Furthermore, findings from this investigation demonstrate that systemic measures of inflammation capture the response to exacerbation treatment and may be used to identify treatment nonresponders sooner. Approximately 25% of CF exacerbations result in permanent loss of lung function despite intensive treatment (14). This is a key morbidity in CF. Our data suggest that a baseline determination of inflammation at the time of exacerbation as well as monitoring changes in circulating inflammatory proteins with antibiotic treatment may identify nonresponders early, providing an opportunity to intervene and modify treatment course.

The strengths of the present study were the assessment of 15 candidate blood-based proteins from more than 100 separate patients with CF experiencing exacerbations meeting a standardized, symptom-based definition. Pulmonary exacerbations are a useful and pragmatic model with which to assess response to treatment. The multicenter design allowed for both older children and adults to be enrolled. Our patients had a broad range of disease severity, representative of the larger CF population. This enabled us to examine the influence of age and disease severity on systemic inflammatory protein levels. Additionally, this study is the first to report on the use of a systemic inflammatory panel, in combination with FEV1, to monitor response to exacerbation treatment and predict which patients fail to recover to their baseline lung function.

The limitations of this study need to be considered. Although the definition of pulmonary exacerbation was protocol defined, treatments were not standardized across sites in this study. Because older children and adults were enrolled, the findings cannot be extrapolated to infants and younger children, in whom exacerbations are common, milder, and generally treated with oral antibiotics (30). We did not assess airway inflammation and cannot determine whether changes in systemic measures of inflammation reflect inflammatory changes in the lungs. Three studies have reported modest correlations between blood-based biomarker levels and select markers of airway inflammation (IL-8, TNF-α, TGF-β1) during CF pulmonary exacerbations (31–33). This suggests that assay of systemic inflammatory markers may, to some extent, reflect inflammatory burden in the lungs. Systemic measures of inflammation appear to have greater value in demonstrating response to exacerbation treatment compared with sputum measurements, as the findings from blood-based measurements across multiple studies have been more consistent (7) than studies relying on sputum assessments, which have yielded conflicting results (20, 34).

In the study from Horsley and colleagues (20), in which both sputum and blood were collected to track changes during CF pulmonary exacerbations, the most significant changes in inflammation were observed in serum rather than sputum. Similarly, data from another study examining the effects of CF pulmonary exacerbation treatment on both systemic and airway inflammation demonstrated a reduction in systemic inflammation after intravenous antibiotics but a persistent inflammatory response in the airways (35). These data suggest that systemic measures of inflammation may be more useful than sputum markers in short-term interventional studies, particularly ones that investigate exacerbation therapies.

In summary, several systemic measures of inflammation have value for demonstrating and predicting clinical response to intravenous antibiotic therapy. Systemic inflammatory markers appear to sensitively detect a meaningful change in lung disease during treatment for CF pulmonary exacerbations. A key next step will be to determine whether monitoring circulating proteins, including their integration in a clinical trial of CF pulmonary exacerbations, improves health outcomes beyond traditional symptom assessment and lung function testing. Systemic markers of inflammation may also prove to be valuable in predicting key clinical events in CF, including lung function decline, future pulmonary exacerbations, and possibly survival (36).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the study site research coordinators listed in the online supplement for helping to enroll patients and coordinating study visits at their sites. They acknowledge assistance from the CFF National Patient Registry Team, including Kirsten Hencken and Alex Elbert, and support for study planning and execution provided by Drs. Preston Campbell and Diana Wetmore. Site monitoring visits were conducted by Lori Muir, C.C.R.A. (ProMedDx, LLC).

Footnotes

Supported by Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics grants SAGEL07B0, SAGEL11CS0, HAMBLE10A0, and KONSTA09Y0, and by the following National Institutes of Health sources: NCATS Colorado grant CTSI UL1 TR000154, grant NIDDK P30 DK089507 (University of Washington), and grant NIDDK P30 DK27651 (Case Western Reserve University).

Author Contributions: S.D.S. and S.L.H. designed the study. S.D.S., J.F.C., G.S.M., S.Z.N., E.P., M.T.S., and B.S. were the lead site investigators, recruited and studied patients at their sites, and reviewed the manuscript. M.M.A. was the lead research coordinator for this study and helped to prepare study-related documents and manuals. P.E. is the Director of the Pediatric Clinical Translational Research Core Laboratory, the site for assay validation and inflammatory protein measurements. S.L.H. and V.T. performed statistical analyses. S.D.S. and S.L.H. prepared the initial draft of the manuscript and incorporated comments and edits from the other study authors.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Rowe SM, Borowitz DS, Burns JL, Clancy JP, Donaldson SH, Retsch-Bogart G, Sagel SD, Ramsey BW. Progress in cystic fibrosis and the CF Therapeutics Development Network. Thorax. 2012;67:882–890. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clancy JP, Jain M. Personalized medicine in cystic fibrosis: dawning of a new era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:593–597. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0785PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer-Hamblett N, Ramsey BW, Kronmal RA. Advancing outcome measures for the new era of drug development in cystic fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:370–377. doi: 10.1513/pats.200703-040BR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stenbit AE, Flume PA. Pulmonary exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17:442–447. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32834b8c04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flume PA, Mogayzel PJ, Jr, Robinson KA, Goss CH, Rosenblatt RL, Kuhn RJ, Marshall BC Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines:treatment of pulmonary exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:802–808. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200812-1845PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sagel SD, Chmiel JF, Konstan MW. Sputum biomarkers of inflammation in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:406–417. doi: 10.1513/pats.200703-044BR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shoki AH, Mayer-Hamblett N, Wilcox PG, Sin DD, Quon BS. Systematic review of blood biomarkers in cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations. Chest. 2013;144:1659–1670. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sagel SD, Heltshe SL, Mayer-Hamblett N, Emmett P, Chmiel JF, Goss CH, Montgomery GL, Nasr SZ, Perkett E, Saavedra MT, et al. Changes in plasma biomarkers in CF pulmonary exacerbations [abstract] Pediatr Pulmonol Suppl. 2010;33:360. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Clinical practice guidelines for cystic fibrosis. Bethesda, MD: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenfeld M, Emerson J, Williams-Warren J, Pepe M, Smith A, Montgomery AB, Ramsey B. Defining a pulmonary exacerbation in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2001;139:359–365. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.117288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns JL, Emerson J, Stapp JR, Yim DL, Krzewinski J, Louden L, Ramsey BW, Clausen CR. Microbiology of sputum from patients at cystic fibrosis centers in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:158–163. doi: 10.1086/514631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Dockery DW, Wypij D, Fay ME, Ferris BG., Jr Pulmonary function between 6 and 18 years of age. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1993;15:75–88. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950150204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders DB, Bittner RC, Rosenfeld M, Hoffman LR, Redding GJ, Goss CH. Failure to recover to baseline pulmonary function after cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:627–632. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-1421OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dovey M, Aitken ML, Emerson J, McNamara S, Waltz DA, Gibson RL. Oral corticosteroid therapy in cystic fibrosis patients hospitalized for pulmonary exacerbation: a pilot study. Chest. 2007;132:1212–1218. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azar RR, Rinfret S, Théroux P, Stone PH, Dakshinamurthy R, Feng YJ, Wu AH, Rangé G, Waters DD. A randomized placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy of antiinflammatory therapy with methylprednisolone in unstable angina (MUNA trial) Eur Heart J. 2000;21:2026–2032. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Versaci F, Gaspardone A, Tomai F, Ribichini F, Russo P, Proietti I, Ghini AS, Ferrero V, Chiariello L, Gioffrè PA, et al. Immunosuppressive Therapy for the Prevention of Restenosis after Coronary Artery Stent Implantation Study. Immunosuppressive therapy for the prevention of restenosis after coronary artery stent implantation (IMPRESS study) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1935–1942. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02562-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sin DD, Lacy P, York E, Man SF. Effects of fluticasone on systemic markers of inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:760–765. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-543OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray RD, Imrie M, Boyd AC, Porteous D, Innes JA, Greening AP. Sputum and serum calprotectin are useful biomarkers during CF exacerbation. J Cyst Fibros. 2010;9:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horsley AR, Davies JC, Gray RD, Macleod KA, Donovan J, Aziz ZA, Bell NJ, Rainer M, Mt-Isa S, Voase N, et al. Changes in physiological, functional and structural markers of cystic fibrosis lung disease with treatment of a pulmonary exacerbation. Thorax. 2013;68:532–539. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moser C, Jensen PO, Pressler T, Frederiksen B, Lanng S, Kharazmi A, Koch C, Høiby N. Serum concentrations of GM-CSF and G-CSF correlate with the Th1/Th2 cytokine response in cystic fibrosis patients with chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection. APMIS. 2005;113:400–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm_142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartl D, Griese M, Kappler M, Zissel G, Reinhardt D, Rebhan C, Schendel DJ, Krauss-Etschmann S, Pulmonary T. Pulmonary T(H)2 response in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected patients with cystic fibrosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiringer K, Treis A, Fucik P, Gona M, Gruber S, Renner S, Dehlink E, Nachbaur E, Horak F, Jaksch P, et al. A Th17- and Th2-skewed cytokine profile in cystic fibrosis lungs represents a potential risk factor for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:621–629. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1150OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollard HB, Ji XD, Jozwik C, Jacobowitz DM. High abundance protein profiling of cystic fibrosis lung epithelial cells. Proteomics. 2005;5:2210–2226. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srivastava M, Eidelman O, Jozwik C, Paweletz C, Huang W, Zeitlin PL, Pollard HB. Serum proteomic signature for cystic fibrosis using an antibody microarray platform. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;87:303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray RD, MacGregor G, Noble D, Imrie M, Dewar M, Boyd AC, Innes JA, Porteous DJ, Greening AP. Sputum proteomics in inflammatory and suppurative respiratory diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:444–452. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-409OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ratjen F, Saiman L, Mayer-Hamblett N, Lands LC, Kloster M, Thompson V, Emmett P, Marshall B, Accurso F, Sagel S, et al. Effect of azithromycin on systemic markers of inflammation in patients with cystic fibrosis uninfected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chest. 2012;142:1259–1266. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dakin C, Henry RL, Field P, Morton J. Defining an exacerbation of pulmonary disease in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31:436–442. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kraynack NC, Gothard MD, Falletta LM, McBride JT. Approach to treating cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations varies widely across US CF care centers. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46:870–881. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brumback LC, Baines A, Ratjen F, Davis SD, Daniel SL, Quittner AL, Rosenfeld M for the ISIS Study Group. Pulmonary exacerbations and parent-reported outcomes in children <6 years with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. [online ahead of print] 29 Apr 2014DOI: 10.1002/ppul.23056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Nixon LS, Yung B, Bell SC, Elborn JS, Shale DJ. Circulating immunoreactive interleukin-6 in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1764–1769. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9704086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colombo C, Costantini D, Rocchi A, Cariani L, Garlaschi ML, Tirelli S, Calori G, Copreni E, Conese M. Cytokine levels in sputum of cystic fibrosis patients before and after antibiotic therapy. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40:15–21. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris WT, Muhlebach MS, Oster RA, Knowles MR, Clancy JP, Noah TL. Plasma TGF-β₁ in pediatric cystic fibrosis: potential biomarker of lung disease and response to therapy. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46:688–695. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ordoñez CL, Henig NR, Mayer-Hamblett N, Accurso FJ, Burns JL, Chmiel JF, Daines CL, Gibson RL, McNamara S, Retsch-Bogart GZ, et al. Inflammatory and microbiologic markers in induced sputum after intravenous antibiotics in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1471–1475. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-731OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Downey DG, Brockbank S, Martin SL, Ennis M, Elborn JS. The effect of treatment of cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations on airways and systemic inflammation. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:729–735. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reid PA, McAllister DA, Boyd AC, Innes JA, Porteous D, Greening AP, Gray RD. Measurement of serum calprotectin in stable patients predicts exacerbation and lung function decline in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:233–236. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201407-1365LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]