Abstract

Background

Drugs can be supplied either directly from the prescribing physician (physician dispensing [PD]) or via a pharmacy. It is unclear whether the dispensing channel is associated with quality problems. Potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) is associated with adverse outcomes in older persons and can be considered a marker for quality deficits in prescribing. We investigated whether prevalence of PIM differs across dispensing channels.

Patients and methods

We analyzed basic health insurance claims of 50,747 person quarter years with PIM use of residents of the Swiss cantons Aargau and Lucerne of the years 2012 and 2013. PIM was identified using the Beers 2012 criteria and the PRISCUS list. We calculated PIM prevalence stratified by supply channel. Adjusted mixed effects logistic regression analysis was done to estimate the effect of obtaining medications through the dispensing physician as compared to the pharmacy channel on receipt of PIM. The most frequent PIMs were identified.

Results

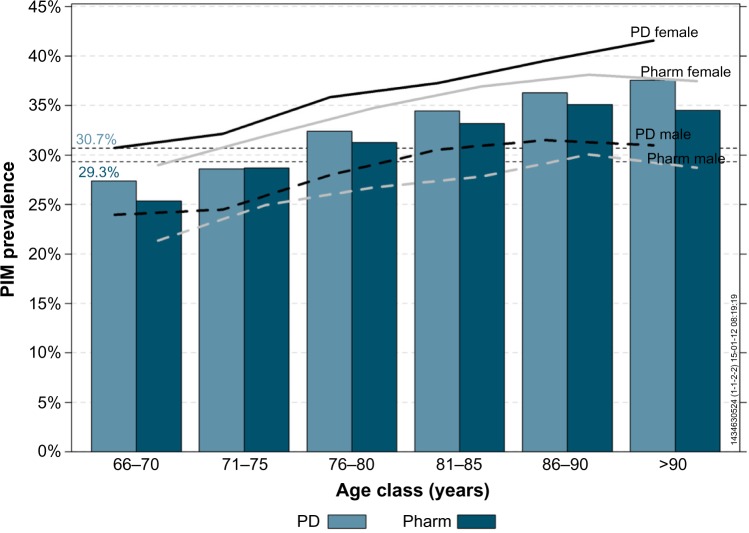

There is a small but detectable difference in total PIM prevalence: 30.7% of the population supplied by a dispensing physician as opposed to 29.3% individuals who received medication in a pharmacy. According to adjusted logistic regression individuals who obtained the majority of their medications from their prescribing physician had a 15% higher chance to receive a PIM (odds ratio 1.15, 95% confidence interval 1.08–1.22; P<0.001).

Conclusion

Physician dispensing seems to affect quality and safety of drug prescriptions. Quality issues should not be neglected in the political discussion about the regulations on PD. Future studies should explore whether PD is related to other indicators of inefficiency or quality flaws. The present study also underlines the need for interventions to reduce the high rates of PIM prescribing in Switzerland.

Keywords: physician dispensing, prescription, drug dispensing, quality, Switzerland

Introduction

In most Western countries, drugs can be supplied either directly from the prescribing physician (physician dispensing [PD]) or via a pharmacy.1 PD allows for additional revenues of physicians in private practices and offers a source of drugs in regions where pharmacies are scarce. However, PD might generate perverse incentives for doctors to prescribe more extensive or more expensive medications.2

Previous studies in Switzerland showed an inconsistent pattern with respect to the effects of PD. Some studies found a positive relationship between PD and medication cost,3,4 whereas others found a negative association.5,6 Total health care cost was slightly increased by PD in one study7 whereas PD slightly diminished total cost in two other studies.6,8 Another study found that PD decreased ambulatory services from primary care providers but increased services provided by specialists.9 The medication supply channel also may influence prescription behavior: antibiotic prescriptions were increased by 0.3% in regions with many dispensing physicians,10 but PD might increase the likelihood of receiving a generic medication.11 However, dispensing physicians may tend to choose medication packet sizes which provide higher sales margins.12

Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) are drugs identified via extensive expert consultation rounds because they are associated with an increased risk of adverse drug reactions in older persons.13 PIMs have been shown to lead to adverse outcomes such as hospitalization, surgery, and death.14,15 There are various initiatives that aim at reducing the prescription rates of PIM.16,17 PIM prescribing can thus be considered an indicator for quality of health care in the older population.18 High prevalence rates of PIM use in the community-dwelling older population have been shown all over Europe19,20 and have also been recently reported for Switzerland.21,22

Given the fact that PD constitutes a considerable part of the income of physicians working in private practices in Switzerland, the question of whether or not physicians should be allowed to sell medicines in addition to the existence of pharmacies is a matter of ongoing debate in Switzerland.8 While many countries prevent physicians from selling drugs directly to their patients to minimize the prescriber’s incentives, PD is allowed in some cantons in Switzerland, whereas it is prohibited in others. This is why Switzerland provides the opportunity for comparisons of both systems. The aim of the present study is to empirically investigate whether the prevalence of PIM prescriptions differs between the two supply settings.

Methods

Source of data

This is a retrospective analysis of persons aged more than 65 years insured in the mandatory health insurance with the Helsana Group (1.2 million individuals insured in 2013) in the years 2012 and 2013. We analyzed medications submitted for reimbursement and covered by mandatory health insurance. All persons residing in Switzerland are required to purchase basic health insurance on a private market of health insurance which is regulated by federal bodies. In order to protect those with poor health, health insurers are obliged to offer basic insurance to everyone and to charge the same price to every individual irrespective of age or health status. The basic health insurance package includes medical treatment deemed appropriate, medically effective, and cost-effective. However, the insured person pays a part of the cost of health care in the form of an annual deductible ranging from CHF300.00 to a maximum of CHF2,500.00 as chosen by the insured person and a charge of 10% of the costs up to CHF700.00 per year. Currently, there are 61 insurance companies providing basic health coverage in Switzerland, and they offer a range of different premiums and types of health plans (ie, managed care plans that trade off lower premiums for reduced choice and more case management) from which Swiss residents are free to choose.

Three of Europe’s major languages (German, French, and Italian) are official in Switzerland. The country is characterized by a large cultural diversity which is reflected in cultural differences in social and health care policy at the regional level and in different attitudes towards the health system.7,23 For example, PD is primarily allowed in the German-speaking cantons as it is a cantonal competence to allow or prohibit PD. It is allowed in the canton of Lucerne and prohibited in the canton of Aargau except for emergencies only. Aargau and Lucerne resemble one another with respect to size, demographic development, unemployment rates, tax levels, mean educational level, and physician density (ca 1,5 physicians per 1,000 inhabitants). Hospitals in the canton of Lucerne function as centers for central Switzerland whereas hospitals in the canton of Aargau focus on rehabilitation. This relates to differences in hospital usage. Given the availability of PD in Lucerne, there are twice as many pharmacies in Aargau as compared to Lucerne.24 Focusing the analyses on the two German-speaking cantons of Aargau and Lucerne the cultural effect can be controlled for.

Nursing home residents were excluded from the analysis as medications prescribed in this setting are usually included in lump sums and not declared separately in detail to the health insurance.

If individuals obtained more than 50% of their drug prescriptions in the years 2012 and 2013 from a dispensing physician, they were allocated to the “PD” (physician dispensing) group. If more than 50% of medications were purchased in a pharmacy, individuals were assigned to the “pharm” (pharmacy supply) group. We analyzed a total of n=50,747 quarter years with PIM use of persons residing in the cantons Aargau and Lucerne.

Definition of PIM

PIMs are single drugs related to an increased risk of adverse drug reactions which should be avoided in older persons. They have been previously identified through expert consensus and listed. In 1997, Beers published the first list of PIMs for elderly persons in the USA25 which has been updated in 200326 and 2012.13 Due to international differences in the availability of drugs and in prescription behavior, several countries developed separate lists adapted to the local contexts such as Canada,27 France,13 or Germany (the PRISCUS list).28 The present analysis used the 2012 Beers criteria13 and the PRISCUS list25 to identify PIM in the data set (independent of diagnosis or conditions). Each active agent and combinations from these lists were attributed one or more Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC) codes.29 The definition of PIM variables accounted for the fact that certain medications were considered inappropriate only above a certain dose or for long-term use.

Statistical analyses

The primary outcome of the analysis was prevalence of PIM use. For every insured person in the analytic study sample, we quarterly checked whether the person had submitted an invoice for medications for the investigated time interval. The unit of analysis were thus person quarter years. We selected this interval because physicians in private practices usually send out invoices quarterly.

Firstly, we used descriptive statistics to analyze the socio-demographic characteristics and markers of health status for the study sample, stratified by whether or not they were classified “PD” or “pharm”. Presence of chronic conditions was evaluated using pharmaceutical cost groups (PCGs) as ambulatory medical diagnosis information is missing in the available data set.30 Differences in cost and health service utilization data were explored using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, a nonparametric test for continuous outcomes and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Prevalence rates of use of at least one PIM per quarter year were calculated stratified for medication supply channel (PD or pharm) and for age class and sex. Prevalence rates were adjusted for differences between the Helsana sample and the general population in Switzerland in terms of age group, sex, and canton of residence.31

Mixed effects logistic regression analysis was done to estimate the effect of obtaining medications through the dispensing physician (PD) as compared to the pharmacy channel (pharm) on receipt of PIM, adjusted for differences in demography (ie, age, sex, employment), health insurance status (ie, annual deductible, managed care option, supplementary hospital insurance), and cost and service utilization parameters (ie, total cost and number of medications in previous year, number of hospitalizations and physician consultations in previous year, number of different physicians consulted in previous year). Finally, the 25 most frequent PIMs in 2012 and 2013, rank-ordered by the total number of recipients were identified. Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated between the rank order of PIM and the supply channel. A two-sided P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R, version 2.14.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Characteristics of the study sample

Table 1 depicts the characteristics of the study sample. Data from a total of 50,747 person quarter years were analyzed. PD individuals who obtained the majority of their medication from the prescribing physician (PD) were slightly older (76.4±6.9 years) than pharm individuals (76.1±6.9 years). Females were more frequent in the pharm group. Those individuals who died in the years 2012 or 2013 were less frequently in the PD group. Persons from the pharm group were better off than those of the PD group as they more frequently had a supplementary hospital insurance or access to additional semi-private or private services. Persons from the pharm group also more frequently chose an annual deductible higher than the obligatory minimum or a managed care plan that trade off lower insurance premiums for reduced choice and more care management. Individuals of the PD group suffered from slightly more chronic conditions, as measured by pharmacy cost groups. However, we did not detect clinically relevant differences in prevalence of different chronic conditions between PD and pharm individuals. Cost parameters (total annual cost, medication cost, and cost for ambulatory services) were higher in the pharm group, and pharm individuals were more frequently hospitalized. Individuals of the PD group obtained more medications overall and, of those, PD patients more frequently had a PIM. Overall, there were substantial crude differences between the two groups. As for parameters of service use and cost, these are most likely related to socioeconomic and health-related differences across regions with and without PD.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the study sample

| Characteristic | N (%) or Mean (median)

|

P-valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharm | PD | Total | ||

| Person quarter years | 36,203 (71.3%) | 14,544 (28.7%) | 50,747 (100%) | |

| Age (years) | 76.1 (75) | 76.4 (76) | 76.1 (76) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 22,891 (72.4%) | 8,738 (27.6%) | 31,629 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Died in 2012 or 2013 | 249 (82.7%) | 52 (17.3%) | 301 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Low annual deductible | 34,431 (71.1%) | 13,976 (28.9%) | 48,407 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Managed care plan | 18,008 (76.4%) | 5,553 (23.6%) | 23,561 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Supplementary hospital insurance | 15,473 (72.7%) | 5,802 (27.3%) | 21,275 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Additional semi-private services | 7,476 (71.9%) | 2,927 (28.1%) | 10,403 (100%) | 0.189 |

| Additional private services | 3,552 (79.7%) | 902 (20.3%) | 4,454 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Number of different medications | 8.2 (7) | 8.6 (8) | 8.4 (7) | <0.001 |

| Number of different PIMs-Medikamente | 1.3 (1) | 1.3 (1) | 1.3 (1) | <0.001 |

| Number of chronic conditions (PCG) | 3.3 (3) | 3.4 (3) | 3.3 (3) | <0.001 |

| Annual total cost (CHF) | 3,276 (1,379) | 2,547 (1,207) | 3,067 (1,324) | <0.001 |

| Annual cost, ambulatory services (CHF) | 2,233 (1,294) | 1,925 (1,155) | 2,145 (1,252) | <0.001 |

| Annual cost, medications (CHF) | 825 (465) | 648 (419) | 774 (450) | <0.001 |

| Annual length of stay in hospital (days) | 5.1 (0) | 3.6 (0) | 4.7 (0) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 hospitalization per year | 10,451 (74.1%) | 3,662 (25.9%) | 14,113 (100%) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 short hospitalizations per year | 3,171 (74.2%) | 1,102 (25.8%) | 4,273 (100%) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 long hospitalizations per yearb | 8,774 (74.8%) | 2,953 (25.2%) | 11,727 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Number of quarter years with PIM use (per year) | 2.9 (3) | 2.8 (3) | 2.9 (3) | <0.001 |

| 1 quarter year with PIM use per year | 6,348 (69.9%) | 2,740 (30.1%) | 9,088 (100%) | <0.001 |

| 2 quarter years with PIM use per year | 6,030 (68.8%) | 2,740 (31.2%) | 8,770 (100%) | |

| 3 quarter years with PIM use per year | 8,189 (68.8%) | 3,712 (31.2%) | 11,901 (100%) | |

| 4 quarter years with PIM use per year | 15,636 (74.5%) | 5,352 (25.5%) | 20,988 (100%) | |

Notes:

Derived from Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous outcomes and chi-squared test for categorical outcomes;

≥3 consecutive nights. Swiss Francs (CHF; December 2014: 1 CHF ~0.93€).

Abbreviations: PCG, pharmaceutical cost group; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication; PD, physician dispensing; Pharm, pharmacy supply.

PIM prevalence according to channel of supply

Figure 1 illustrates the crude differences of PIM prevalence in those who obtained their medication from the prescribing physician (PD) and those who bought medication in pharmacies (pharm). There is a small but detectable difference in total PIM prevalence: 30.7% in PD as opposed to 29.3% in pharm individuals. These differences are measurable across all age groups investigated and for both men and women. It should be emphasized that, irrespective of the supply channel, more than a quarter of all older persons obtained at least one PIM per quarter year.

Figure 1.

Proportion of persons with PIM use by supply channel, sex, and age class.

Abbreviations: PIM, potentially inappropriate medication; PD, physician dispensing; Pharm, pharmacy supply.

Mixed effects logistic regression analysis

We estimated the effect of obtaining medications through the PD as compared to the pharmacy channel (pharm) on receipt of PIM using mixed effects logistic regression analysis adjusted for differences in demography, health insurance status, cost and service utilization parameters. The odds ratio derived from our logistic regression model was 1.15 (95% confidence interval 1.08–1.22, P<0.001). This means that individuals who obtained the majority of their medications from their prescribing physician had a 15% higher chance to receive a PIM.

Most frequent PIMs

Table 2 rank orders the 25 most frequent PIMs in 2012 and 2013 by the total number of recipients. Psycholeptics (ATC code starting with N05) were the most frequently prescribed PIM group including zolpidem, oxazepam, bromazepam, quetiapine, alprazolam, risperidone, and hydroxyzine. Four of the most frequently prescribed PIMs were anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic products (ATC code starting with M01). Drugs for cardiac therapy (ATC code starting with C01) were also among the most frequent PIMs: amiodarone, epinephrine, and digoxin. Drugs for functional gastrointestinal disorders (ATC code starting with A03) were frequently represented PIMs in the data set as well.

Table 2.

Most frequent PIMs in 2012 and 2013, rank-ordered by total number of recipients

| Rank Total | PIM (ATC code) | Substance | PD | Rank | Pharm | Rank | PD | Rank | Pharm | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| 2012 | 2013 | |||||||||

| 1 | N05CF02 | Zolpidem | 8,337 | 1 | 13,367 | 1 | 8,418 | 1 | 13,213 | 1 |

| 2 | N05BA04 | Oxazepam | 3,323 | 3 | 7,084 | 2 | 3,117 | 5 | 6,509 | 2 |

| 3 | M01AB11 | Acemetacin | 3,899 | 2 | 5,701 | 4 | 3,837 | 3 | 5,555 | 6 |

| 4 | N05BA08 | Bromazepam | 2,941 | 7 | 6,719 | 3 | 2,856 | 7 | 6,449 | 3 |

| 5 | A03FA01 | Metoclopramide | 3,266 | 4 | 5,467 | 5 | 3,171 | 4 | 5,671 | 5 |

| 6 | A03B | Belladonna alkaloids | 3,202 | 5 | 4,217 | 6 | 4,284 | 2 | 5,841 | 4 |

| 7 | M01AB05 | Diclofenac | 3,202 | 5 | 3,585 | 7 | 3,018 | 6 | 3,296 | 8 |

| 8 | N05AH04 | Quetiapine | 1,508 | 14 | 3,582 | 8 | 1,804 | 12 | 3,963 | 7 |

| 9 | C01BD01 | Amiodarone | 1,955 | 9 | 3,090 | 9 | 2,016 | 9 | 3,046 | 10 |

| 10 | R05DA20 | Dextromethorphan | 2,361 | 8 | 2,448 | 14 | 2,358 | 8 | 2,437 | 14 |

| 11 | C01CA24 | Epinephrine | 1,761 | 10 | 2,863 | 10 | 1,870 | 11 | 3,094 | 9 |

| 12 | M01AH05 | Etoricoxib | 1,757 | 11 | 2,417 | 15 | 1,933 | 10 | 2,666 | 11 |

| 13 | M01AE01 | Ibuprofen | 1,603 | 12 | 2,623 | 11 | 1,592 | 14 | 2,620 | 12 |

| 14 | G03CA | Etinylestradiol | 1,501 | 15 | 2,467 | 13 | 1,482 | 15 | 2,385 | 15 |

| 15 | N06AA06 | Trimipramin | 1,564 | 13 | 1,919 | 19 | 1,598 | 13 | 1,927 | 19 |

| 16 | C01AA05 | Digoxin | 1,287 | 19 | 2,285 | 16 | 1,210 | 18 | 2,064 | 18 |

| 17 | N05BA12 | Alprazolam | 850 | 25 | 2,587 | 12 | 876 | 23 | 2,519 | 13 |

| 18 | A06AA01 | Paraffin oil | 1,075 | 20 | 2,133 | 17 | 1,173 | 20 | 2,122 | 17 |

| 19 | C03DA01 | Spironolactone | 1,347 | 16 | 1,890 | 20 | 1,358 | 16 | 1,837 | 20 |

| 20 | J01XE01 | Nitrofurantoin | 880 | 23 | 2,019 | 18 | 1,031 | 21 | 2,354 | 16 |

| 21 | M01AG01 | Mefenamic acid | 1,307 | 17 | 1,537 | 23 | 1,285 | 17 | 1,396 | 24 |

| 22 | N05AX08 | Risperidone | 895 | 21 | 1,816 | 21 | 860 | 24 | 1,759 | 21 |

| 23 | N02AB02 | Pethidine | 1,290 | 18 | 1,402 | 25 | 1,201 | 19 | 1,282 | 25 |

| 24 | A10AB05 | Sliding scale insulin | 885 | 22 | 1,497 | 24 | 926 | 22 | 1,626 | 22 |

| 25 | N05BB01 | Hydroxyzine | 876 | 24 | 1,576 | 22 | 834 | 25 | 1,585 | 23 |

Abbreviations: PIM, potentially inappropriate medication; ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System; PD, physician dispensing; Pharm, pharmacy supply.

The pattern of the most frequently used PIMs was quite similar in both groups. There might be a trend for a more frequent use of trimipramine (psychoanaleptic) and pethidine (an opioid) in PD and a more frequent use of nitrofurantoin (an antibacterial) in pharm individuals. Apart from these trends, we did not recognize a clear pattern indicating that a certain group of medications was extraordinarily more frequently used in PD as compared to pharm. There was also very little change in the rank orders between the years 2012 and 2012 (Table 2). The Spearman correlation coefficient between the rank order of PIM and the supply channel was high (r=0.82, P<0.001 for 2012, and r=0.85, P<0.001 for 2013). This means that there is a tendency for ranks of PIM between PD and pharm to be paired together.

Discussion

The present study provides indication that there may be quality problems associated with dispensing of medication by the prescribing physician. Receiving the majority of drugs directly from a dispensing physician seems to be a significant risk factor for PIM prescriptions. The extent rates of PIMs that are attributable to PD are small. However, the vulnerable population at risk for adverse events due to PIMs is large so that even small differences in prescription rates may cause large effects on the health system level.

The overall results of this study are well in line with a growing body of evidence indicating the importance of improving prescribing practices and drug safety in the ambulatory setting.19–22 A previous analysis of claims data found a PIM prevalence of 21% in the community-dwelling older population in Switzerland.22 However, PIM definition of this previous study was based on the 2003 Beers criteria. The Beers criteria update in 2012 used in the present analysis extended the list of PIMs so that the PIM prevalence of circa 30% found in the present study is plausible. The detected sex differences in PIM prevalence are also in line with previous investigations.21,22

Several limitations of the present study need to be considered. Firstly, the analyses considered all health care invoices submitted to Helsana for reimbursement, and invoices of persons whose health care expenses did not exceed the annual deductible may have been missed. However, internal analyses done by Swiss health insurances showed that this proportion is about 2%–3% of invoices, so a potential selection bias is likely to be very small. Secondly, given the fact that the analysis was based on invoices, we can conclude the number of medications that has been prescribed and obtained but not on the number of medications that has actually been consumed. It can be assumed that a considerable number of prescriptions were not consumed. Thirdly, we analyzed claims data of basic health insurance without considering data from private supplementary insurances. However, basic health insurance accounts for 80% of medication costs in Switzerland so it is unlikely that inclusion of private insurance would significantly affect the study results. Fourthly, nursing home residents were excluded from the analyses so it is unclear whether the results can be generalized to the long-term care setting.

The present estimates for prevalence rates were adjusted for slight differences between the analytic study sample and the total population in Switzerland in terms of age, sex, and canton of residence to take into account that we analyzed data from a single health insurance group. In addition, our results should be verified with data from other Swiss cantons to exclude an effect of geographic or cultural factors that are specific to the cantons of Aargau and Lucerne which we were not able to control for. Furthermore, the definition of PD or pharm was attributed on the person level based on the channel an individual obtained the majority of his or her medication. Future analyses assigning the supply channel definition on the medication level may be helpful to minimize the effect of patient characteristics and the number and coordination of health care providers involved in the care.

However, to our knowledge, this is the first study investigating a potential impact of PD on the quality of medication prescription in Switzerland. Thus, the present analysis is an absolute novelty and an important contribution to health policy. So far, discussions about future regulations of PD in Switzerland have concentrated on the potential economic effects especially for service providers who will be cut off from additional income. The question of whether or not there might also be quality differences that need to be considered has not yet been given sufficient attention.

Clearly, prohibiting PD in Switzerland will not solve the problem of PIM prescription in Switzerland. In contrast, a broad spectrum of interventions on the individual level as well as on the population level is urgently needed. In recent years, a wide range of efforts has been made internationally to reduce PIM such as the development of lists and tools32–34 for identification and reduction of problematic drugs, educational programs,35 comprehensive geriatric assessment or geriatric care teams,36 information and communication technology interventions,37–38 or medication review by different types of health professionals.39 For example, pharmacists can help reduce PIM prescriptions by drug-drug interaction and dose checking, and patient instruction in reducing PIM prescriptions.37,40

Most of these interventions are based on interdisciplinary, intersectoral, and/or interprofessional teamwork. A large body of evidence supports the extraordinary role of collaboration between different groups of service providers in health care.41 Previous research indicates the great potential of such approaches with respect to reducing economic waste and improving quality and safety of care.42–44 PD is, in principle in contrast with new collaborative approaches and attitudes as a single person is responsible for the complete process from the assessment of the indication to the distribution of a drug. It is likely that the “four eyes principle” supports quality of prescribing in the ambulatory setting.

Conclusion

Apparently, PD affects quality and safety of drug prescriptions. We argue that quality issues should not be neglected in the political discussion about the regulations on PD. Future studies should explore whether PD is related to other indicators of inefficiency or quality flaws. The present study also underlines the need for interventions to reduce the high rates of PIM prescribing in Switzerland.

Acknowledgments

This study was done with own resources of the Helsana Group, Zürich, Switzerland.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Eggleston K. Prescribing institutions: Explaining the evolution of physician dispensing. Journal of Institutional Economics. 2012;8(2):247–270. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu YM, Yang YH, Hsieh CR. Financial incentives and physicians’ prescription decisions on the choice between brand-name and generic drugs: evidence from Taiwan. J Health Econ. 2009;28(2):341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ideas.reprec.org [homepage on the Internet] Kaiser B, Schmid C. Does Physician Dispensing Increase Drug Expenditures? Discussion paper number dp1303. Department of Economics, University of Bern; Switzerland: 2013. [Accessed November 24, 2014]. Available from: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ube/dpvwib/dp1303.html/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck K, Kunze U, Oggier W. [Physician dispensing: cost driving or cost limiting factor]. Selbstdispensation: Kosten treibender oder Kosten dämpfender Faktor? Managed Care. 2004;8:33–36. German. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schleiniger R, Slembeck T, Blöchlinger J. Bestimmung und Erklärung der kantonalen Mengenindizes der OKP-Leistungen. Winterthur: Zurich University of Applied Sciences; 2007. German. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trottmann M. Information Asymmetries and Incentives in Health Care Markets [dissertation] Zurich: University of Zurich; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reich O, Weins C, Schusterschitz C, Thöni M. Exploring the Disparities of Re-gional Health Care Expenditures in Switzerland: Some Empirical Evidence. Eur J Health Econ. 2012;13(2):193–202. doi: 10.1007/s10198-011-0299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vatter A. Ruedi C. Do Political Factors Matter for Health Care Expenditure? A Comparative Study of Swiss Cantons. J Public Policy. 2003;23:301–323. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busato A, Matter P, Künzi B, Goodman DC. Supply sensitive services in Swiss ambulatory care: an analysis of basic health insurance records for 2003–2007. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:315. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filippini M, Masiero G, Moschetti K. Dispensing Practices and Antibiotic Use. University of Lugano; 2008. [Accessed November 25, 2014]. Available from: https://doc.rero.ch/record/10674/files/wp0808.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rischatsch M, Trottmann M, Zweifel P. Generic Substitution, Financial Interests, and Imperfect Agency. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2013;13(2):115–138. doi: 10.1007/s10754-013-9126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rischatsch M. Lead Me not into Temptation: Drug Price Regulation and Dispensing Physicians in Switzerland. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(7):697–708. doi: 10.1007/s10198-013-0515-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruggiero C, Dell‘Aquila G, Gasperini B, et al. Potentially inappropriate drug prescriptions and risk of hospitalization among older, Italian, nursing home residents: the ULISSE project. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(9):747–758. doi: 10.2165/11538240-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klarin I, Wimo A, Fastbom J. The association of inappropriate drug use with hospitalisation and mortality: a population-based study of the very old. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(1):69–82. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clyne B, Bradley MC, Hughes CM, et al. Addressing potentially inappropriate prescribing in older patients: development and pilot study of an intervention in primary care (the OPTI-SCRIPT study) BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:307. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forsetlund L, Eike MC, Gjerberg E, Vist GE. Effect of interventions to reduce potentially inappropriate use of drugs in nursing homes: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frankenthal D, Lerman Y, Kalendaryev E, Lerman Y. Intervention with the screening tool of older persons potentially inappropriate prescriptions/screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment criteria in elderly residents of a chronic geriatric facility: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(9):1658–1665. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hovstadius B, Hovstadius K, Astrand B, Petersson G. Increasing polypharmacy – an individual-based study of the Swedish population 2005–2008. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2010;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slabaugh SL, Maio V, Templin M, Abouzaid S. Prevalence and risk of polypharmacy among the elderly in an outpatient setting: a retrospective cohort study in the Emilia-Romagna region, Italy. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(12):1019–1028. doi: 10.2165/11584990-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reich O, Rosemann T, Rapold R, Blozik E, Senn O. Potentially inappropriate medication use in older patients in Swiss managed care plans: prevalence, determinants and association with hospitalization. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blozik E, Rapold R, von Overbeck J, Reich O. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication in the adult, community-dwelling population in Switzerland. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(7):561–568. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crivelli L, Filippini M, Mosca I. Federalism and regional health care expenditures: an empirical analysis for the Swiss cantons. Health Econ. 2006;15(5):535–541. doi: 10.1002/hec.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Interface Comparative Portrait Of Cantons Aargau And Lucerne; 2010. [Accessed January 6, 2015]. Available from: http://www.raonline.ch/pages/ag/pdf/AG-LU-Portrait2010.pdf. German.

- 25.Beers MH. Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(14):1531–1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2716–2724. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Merle L. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: a French consensus panel list. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(8):725–731. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thurmann PA. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: the PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107(31–32):543–551. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization [homepage on the Internet] ATC/DDD Index. 2015. [Accessed February 11, 2015]. Available from: http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/

- 30.Huber CA, Szucs TD, Rapold R, Reich O. Identifying patients with chronic conditions using pharmacy data in Switzerland: an updated mapping approach to the classification of medications. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1030. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swiss Federal Office of Statistics [homepage on the Internet] Mittlere ständige Wohnbevölkerung. [Mean permanent resident population] [Accessed February 11, 2015]. Available from: http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/01/02/blank/dos/mittlere/01.html. German.

- 32.Gallagher PF, O’Connor MN, O’Mahony D. Prevention of potentially inappropriate prescribing for elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial using STOPP/START criteria. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89(6):845–854. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samsa GP, Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, et al. A summated score for the medication appropriateness index: development and assessment of clinimetric properties including content validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(8):891–896. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barry PJ, Gallagher P, Ryan C, O’mahony D. START (screening tool to alert doctors to the right treatment)-an evidence-based screening tool to detect prescribing omissions in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 2007;36(6):632–638. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keijsers CJ, van Hensbergen L, Jacobs L, et al. Geriatric pharmacology and pharmacotherapy education for health professionals and students: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74(5):762–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmader KE, Hanlon JT, Pieper CF, et al. Effects of geriatric evaluation and management on adverse drug reactions and suboptimal prescribing in the frail elderly. Am J Med. 2004;116(6):394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curtain C, Peterson GM. Review of computerized clinical decision support in community pharmacy. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;39(4):343–348. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arditi C, Rège-Walther M, Wyatt JC, Durieux P, Burnand B. Computer-generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals; effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD001175. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001175.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, Samsa GP, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a clinical pharmacist intervention to improve inappropriate prescribing in elderly outpatients with polypharmacy. Am J Med. 1996;100(4):428–437. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)89519-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spinewine A, Fialová D, Byrne S. The role of the pharmacist in optimizing pharmacotherapy in older people. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(6):495–510. doi: 10.2165/11631720-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nkansah N, Mostovetsky O, Yu C, Chheng T, Beney J, Bond CM, Bero L. Effect of outpatient pharmacists’ non-dispensing roles on patient outcomes and prescribing patterns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;7:CD000336. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000336.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holden LM, Watts DD, Walker PH. Communication and collaboration: it’s about the pharmacists, as well as the physicians and nurses. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(3):169–172. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.026435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mosadeghrad AM. Factors influencing healthcare service quality. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(2):77–89. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niquille A, Ruggli M, Buchmann M, Jordan D, Bugnon O. The nine-year sustained cost-containment impact of Swiss pilot physicians-pharmacists quality circles. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(4):650–657. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]