Abstract

Background

No studies have estimated the population-level burden of morbidity in individuals diagnosed with cancer as children (ages 0-19 years). We updated prevalence estimates of childhood cancer survivors as of 2011 and burden of morbidity in this population reflected by chronic conditions, neurocognitive dysfunction, compromised health-related quality of life and health status (general health, mental health, functional impairment, functional limitations, pain and fear/anxiety).

Methods

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program data from 1975 to 2011 were used to update the prevalence of survivors of childhood cancers in the US. Childhood Cancer Survivor Study data were used to obtain estimates of morbidity burden indicators which were then extrapolated to SEER data to obtain population-level estimates.

Results

There were an estimated 388,501 survivors of childhood cancer in the US as of January 1, 2011, of whom 83.5% are ≥5 years post-diagnosis. The prevalence of any chronic condition among ≥5-year survivors ranged from 66% (ages 5-19) to 88% (ages 40-49). Estimates for specific morbidities ranged from 12% (pain) to 35% (neurocognitive dysfunction). Generally, morbidities increased by age. However, mental health and anxiety remained fairly stable and neurocognitive dysfunction exhibited initial decline and then remained stable by time since diagnosis.

Conclusions

The estimated prevalence of survivors of childhood cancer is increasing, as is the estimated prevalence of morbidity in those ≥5 years post-diagnosis.

Impact

Efforts to understand how to effectively decrease morbidity burden and incorporate effective care coordination and rehabilitation models to optimize longevity and well-being in this population should be a priority.

Keywords: childhood cancer survivors, chronic conditions, neurocognitive functioning, health-related quality of life, health status

Introduction

Estimates of the overall 5-year survival rates for childhood cancers have steadily increased since the 1970s and are currently over 80%[1]. While increased survival rates are promising, the low specificity of curative treatments for childhood cancer often results in long-term and late effects due to their impact on normal healthy tissues [2]. Thus, survivors of childhood cancer are at an increased risk of adverse health and quality of life outcomes compared to individuals without a cancer history [3]. These include increased number and severity of chronic health conditions [4, 5], health limitations [6, 7], hospitalizations [8, 9], premature frailty [10], psychological distress [11], neurocognitive dysfunction [11, 12] and reduced productivity (i.e. inability to work or limitation in amount/kind or work) due to health problems [6]. Adult survivors of childhood cancers also report poorer overall health [6, 13] and physical health-related quality of life (HRQOL; [11]). Prevalence for most of these adverse outcomes is estimated from individual cohort studies with less known about the burden of morbidity in childhood cancer survivors at the population level. As the number of survivors is expected to continue to increase due to increased incidence [14] and advances in lifesaving treatments, defining the public health and health care implications of childhood cancer survivors is an important next step.

While no U.S. population-based study of childhood cancer survivors exists, the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), provides rich, high-quality data on a range of potential adverse and late effects of cancer treatment [15-17]. CCSS is a large, geographically and socioeconomically diverse, retrospectively established cohort study that prospectively follows health and disease outcomes in individuals from 26 North American pediatric cancer hospitals who were diagnosed with cancer during childhood or adolescence and survived at least five-years. Using statistical models, data relevant to morbidity can be extrapolated from CSSS and applied to population-level survivorship prevalence data from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program, a collection of population-based registries of cancer incidence and survival in the United States (http://seer.cancer.gov). Combining CCSS and SEER data can provide an estimation of the population-level burden of morbidity in absolute numbers of affected childhood cancer survivors rather than relying only on CCSS data.

The purpose of the present study is two-fold: 1) to update previously published [16] prevalence estimates of childhood cancer survivors in the U.S. through 2011 using SEER and 2) to estimate the burden of morbidity among ≥ 5-year survivors of childhood cancer in the U.S.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

SEER Data

SEER[18] data on incidence and survival from cancers diagnosed in individuals ≤19 years of age from 1975-2011 in 9 SEER registries including the states of Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, and Utah and the metropolitan areas of Atlanta, Detroit, San Francisco-Oakland, and Seattle/Puget Sound were used to estimate prevalence. These registries represent ∼ 10% of the U.S. population. Cancer sites considered for prevalence estimates are those identified by the International Classification for Childhood Cancer ICD-O3 codes consistent with other publications using these data [19, 20]. To match CCSS and SEER data, cancer sites were restricted to those in the CCSS study: leukemia, brain and central nervous system tumors, Hodgkin's lymphoma, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, renal tumors, neuroblastoma, soft tissue and bone tumors. CCSS brain tumors that were either germ cells or benign/borderline were excluded from CCSS data to better align with the SEER histology data. We used population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau in the SEER*stat software [21].

CCSS Burden of Morbidity Data

The CCSS cohort includes over 14,000 long-term survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed between 1970 and 1986. Since enrollment in 1994 to 1998, participants have been periodically surveyed to track health outcomes, health care use patterns, and health behaviors and practices. The CCSS cohort study design and methodology have been previously described [15-17]. The prevalence of factors contributing to the morbidity burden in survivors of childhood cancer 5 or more years following diagnosis was estimated using self-reported CCSS cohort data. These factors include chronic health conditions, neurocognitive functioning, HRQOL and health status indicators. Table 1 summarizes the measures, cut-off values and assessment time points used to estimate morbidity burden in the present study. For the purposes of this study, only CCSS survivors diagnosed between 1970 and 1986, who were aged 0-19 at diagnosis were included to provide as similar a population to that in SEER as possible. Survivors with germ cell tumors (n=62) were excluded because these tumor types were only captured for central nervous system patients and brain in the CCSS cohort. Survivors with benign or borderline brain and central nervous system tumors were also removed (n=35) because these data were not incorporated into SEER until 2004.

Table 1. Measures, Cut-off Values and Time Schedule of Data Collection for Burden of Morbidity Outcomes in CCSS.

| Morbidity Outcome | Measure Description | Cut-off Value Used to Indicate Compromised Functioning, Impairment or Severity | Assessment Time point | # of survivors with data | # of records in model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (1994-98) | 2000 | 2003 | 2007 | |||||

| Chronic Conditions/Second Cancers [4] | Self-reported or proxy-reported (if <18 years of age or deceased at the time of the questionnaire):

|

Severity determined by the Common Terminology for Adverse Events (version4.03) [39]:

|

X | X | X | X | 13,974 | 32,471 |

| Neurocognitive Functioning: CCSS Neurocognitive Questionnaire [12, 40, 41] | Assesses degree (never, sometimes, often) to which participants experience any of 25 problems over the past 6 months. Has 4 subscales:

|

T score <10th percentile of sibling groups' norm (i.e. ≥ 63) on any subscale [12] | X | 7,228 | 7,228 | |||

| HRQOL: SF-36[42, 43] | Assesses 8 health-related dimensions: physical functioning, physical limitations, pain, behavior disturbances due to emotional problems, mental capacity, perceptions of health, social functioning, and feelings of energy/fatigue. Yields 2 component measures:

|

Score ≤ 40 on either PCS or MCS subscales | X | 7,228 | 7,228 | |||

| Health Status Indicators[24] | ||||||||

| General Health | In general, would you say that your health is excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? | Report fair/poor health | X | X | X | 11,634 | 20,994 | |

| Mental Health | Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI-18) to assess psychological symptoms on 3 symptom-specific subscales: depression, somatization, and anxiety | T scores ≥ 63 on any of the 3 symptom specific subscales [24] | X | X | X | 11,634 | 20,994 | |

| Functional Impairment | Any impairment (yes/no) or health problems resulting in:

|

Positive response to a, b, or c | X | X | 10,946 | 15,569 | ||

| Limitations in Activity | How long (≥ 3months, <3 months or not all), over the last 2 years, was your health limited in:

|

Report limitation on a, b, or c for ≥3 months | X | X | 10,946 | 15,569 | ||

| Pain | Do you currently have pain as a result of your cancer or its treatment? (yes/no) | Reported medium to excruciating pain | X | X | 11111 | 16401 | ||

| Anxiety/Fear | Do you currently have anxiety/fears as a result of your cancer or its treatment? | Reported medium to very many, extreme anxiety/fears | X | X | X | 11634 | 20994 | |

Data Analyses

Prevalence of Childhood Cancer Survivors

Data on incidence and survival from 1975-2011 from the SEER registries were used to update prevalence estimates of childhood cancer survivors by anatomic sites and all cancer sites, combined, in the U.S. through January 1, 2011. The number of people in the United States alive in 2011 and diagnosed with cancer between ages 0 and 19 years was calculated in 3 steps. First, the proportion of survivors alive in the SEER-9 areas diagnosed with childhood cancer at ages 0 to 19 years between the years 1975-2011 was calculated by cancer site, sex, race (White, Black, other; where unknown race was grouped with White race) and age using the SEER*Stat software [21] and the counting method [22]. Second, to estimate complete U.S. childhood cancer survivor prevalence, the site/sex/race/age-specific SEER cancer prevalence proportions were multiplied by the respective U.S. sex/race/age-specific populations. To obtain overall prevalence, these categories were summed. Third, complete prevalence of childhood cancer, which includes childhood cancers diagnosed prior to 1975 (i.e. with ≥36 years from prevalence date), was calculated using the CHILDPREV method [16, 23]. Briefly, this method estimates the long-term childhood cancer survivors, diagnosed prior to 1975, using age and period parametric cancer site/sex- specific incidence and survival models fitted to SEER data. Prevalence was examined by sex, age at prevalence estimate (0-19, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59 and ≥60 years) and cancer type (leukemia, acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, brain/central nervous system, neuroblastoma and other peripheral nervous cell tumor, renal tumors, malignant bone tumors, osteosarcoma, Ewing tumor and related sarcomas of bone, soft tissue and other extraosseous sarcomas, germ cell and trophoblastic tumors and neoplasms of gonads).

Representativeness of CCSS

To ensure the CCSS data was representative of the larger U.S. population of childhood cancer survivors, prevalence of all cancers by age at diagnosis (0-4, 5-9, 10-14 and 15-19 years), sex and race (white/unknown, black or other) and each cancer type listed, above, were calculated and compared for the SEER population-based and CCSS samples.

Burden of Morbidity

To estimate the burden of morbidity of US childhood cancer survivors, data on chronic conditions, neurocognitive dysfunction, HRQOL and health status indicators were extrapolated from CCSS to US prevalence data. Some adjustments were made to combine morbidity proportions from CCSS and SEER prevalence data to reflect the CCSS sample: i) prevalence estimates were restricted to people who survived ≥5 years; ii) complete prevalence up to 36 years duration was used instead of complete prevalence because this was the maximum length of follow-up for CCSS data; and ii) only cancers considered in CCSS were included.

We used a logistic regression model to estimate prevalence of morbidities as the proportion of subjects who had experienced the binary outcome of interest as of a specified post-diagnosis period (or age). At risk subjects were classified into prevalent cases vs. non-cases at each interval using reported age at onset (chronic conditions, assessed retrospectively) or age at assessment time point (all other variables). Given the follow-up time frame for the CCSS cohort, we were only able to estimate the burden of morbidity indicators up to 36 years post-diagnosis for survivors 5-49 years of age. Binary outcome variables examined included presence of: a) any (Grade 1-4) chronic conditions; b) any grade 1 (mild) or Grade 2 (moderate) and any Grade 3 (severe) or Grade 4 (life-threatening or disabling) chronic conditions; c) multiple (≥2 and ≥ 3) Grade 3 or 4 chronic conditions [4]; d) neurocognitive dysfunction; e) compromised mental or physical HRQOL and f) moderate to extreme impairments in health status indicators [24] including general health, mental health, functional status, functional limitations, pain and anxiety/fear.

Chronic conditions were assessed at multiple time points. Thus, a participant could contribute observations in more than one follow-up/age period. Survivors with the onset of the condition prior to a given time period were assumed to have the condition in subsequent periods. The remainder of the health outcomes were obtained from one or more questionnaire time points (see Table 1) and were evaluated at the time points post-diagnosis at which they were assessed. If a survivor completed two questionnaires within the same age or time since diagnosis interval, data from the later questionnaire were used. Table 1 provides detailed information on the number of unique cases and number of records used in analyses for each morbidity indicator. As chronic conditions were the most frequently assessed morbidity indicator, the sample and record size was largest for these outcomes. Because the remaining morbidity outcomes were obtained at varying frequencies, the denominators for these outcomes differ. Estimates for health status indicators do not include the 5-19 year age group because the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) assessment was limited to those subjects ≥ 18 years of age. Neurocognitive functioning and HRQOL were only assessed at 2003 follow-up when all survivors were ≥14 years post-diagnosis. Consequently, estimates for these factors were limited to survivors 15-36 years post-diagnosis.

Logistic regression models were fit for each binary outcome, incorporating years post-diagnosis and age at that observation time, controlling for impact of sex, as needed. Since most individuals contributed multiple records to the analysis via the multiple time point scenario developed for the morbidity indicators assessed at multiple time points, the analysis utilized generalized linear models, with generalized estimating equations and robust sandwich variance estimates to account for intra-person correlation [25]. Predicted probability estimates from the models provided estimates of the prevalence of morbidity indicators, along with associated confidence intervals and p-values for comparisons between groups defined by covariate levels. Once final models were obtained for US cancer prevalence and CCSS morbidity prevalence, combined estimates of the burden of morbidity after cancer for this subset of the U.S. population were obtained by multiplying the CCSS morbidity prevalence by the relevant number of SEER cancer survivors within the equivalent age/follow-up periods.

Results

SEER Prevalence Estimates

A total of 388,501 survivors of childhood cancer are estimated to be alive in the United States as of January 1, 2011 (Table 2). Of these, 83.5% had survived >5 years since their original diagnosis and 44.9% had survived ≥ 20 years. The cancer sites with the largest number of survivors were leukemia (75,677), brain (60,540), germ cell and trophoblastic tumors and neoplasms of gonads (38,439), and renal tumors (23,990). The proportion of long-term (≥ 20 years) survivors varied by cancer site. Sites with the largest proportions of longer term survivors were: Germ cell, trophoblastic tumors and neoplasms of gonads (58%); renal (58%); soft tissues (57%) and Hodgkin lymphoma (48%). ALL was the site with the smallest proportion of long-term survivors with only 23% surviving ≥ 20 years. Childhood cancer survivors ≥60 years represented 5% of all childhood cancer survivors. Germ cell, trophoblastic tumors and neoplasms of gonads (17.7%) and soft tissues (14.6%) cancer sites had the largest proportion of survivors ≥60 years of age.

Table 2. SEER Estimates of the Number of People Previously Diagnosed with Cancer as Children (Ages 0-19 Years) in the United States and Alive January 1, 2011 by International Classification of Childhood Cancer (ICCC) Group, Age, Time Since Diagnosis and Gender.

| Complete Prevalence Counts by Age at Prevalence | Time since diagnosis (in years) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Gender/age | 0-19 | 20-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | 60+ | All ages | < 5 | 5 to 10 | 10 to <15 | 15 to <20 | ≥20 | ≥36 |

| All Sites | Both | 114,469 | 96,086 | 63,670 | 56,072 | 39,055 | 19,149 | 388,501 | 64,105 | 56,369 | 49,311 | 44,394 | 174,322 | 73,757 |

| Male | 61,300 | 50,413 | 31,574 | 25,285 | 16,475 | 9,976 | 195,023 | 33,865 | 30,060 | 25,669 | 22,928 | 82,501 | 32,774 | |

| Femalec | 53,169 | 45,673 | 32,096 | 30,787 | 22,580 | 9,173 | 193,478 | 30,241 | 26,309 | 23,642 | 21,465 | 91,821 | 40,983 | |

| I Leukemia | Both | 35,982 | 20,750 | 11,794 | 5,282 | 1,659 | 210 | 75,677 | 15,512 | 13,991 | 11,847 | 10,349 | 23,977 | 4,269 |

| Male | 19,822 | 10,941 | 6,006 | 2,737 | 766 | 92 | 40,364 | 8,401 | 7,946 | 6,368 | 5,498 | 12,151 | 1,924 | |

| Female | 16,160 | 9,809 | 5,788 | 2,545 | 893 | 118 | 35,313 | 7,111 | 6,045 | 5,479 | 4,851 | 11,826 | 2,345 | |

| Acute lymphocytic leukemia | Both | 30,395 | 16,935 | 9,972 | 4,732 | 564 | 3 | 62,601 | 12,299 | 11,277 | 10,063 | 8,626 | 20,335 | 3,265 |

| Male | 16,803 | 9,125 | 5,220 | 2,611 | 308 | 2 | 34,069 | 6,818 | 6,440 | 5,441 | 4,735 | 10,635 | 1,696 | |

| Female | 13,592 | 7,810 | 4,752 | 2,121 | 256 | 1 | 28,532 | 5,481 | 4,838 | 4,622 | 3,891 | 9,700 | 1,569 | |

| I(b) Acute myeloid leukemia | Both | 3,992 | 2,528 | 1,185 | 690 | 245 | 4 | 8,644 | 2,221 | 1,944 | 1,298 | 1,167 | 2,015 | 499 |

| Male | 2,075 | 1,183 | 498 | 321 | 137 | 3 | 4,217 | 1,028 | 1,099 | 694 | 515 | 881 | 265 | |

| Female | 1,917 | 1,345 | 687 | 369 | 108 | 1 | 4,427 | 1,193 | 845 | 604 | 652 | 1,134 | 234 | |

| II(a) Hodgkin lymphoma | Both | 4,863 | 8,832 | 8,058 | 7,834 | 5,056 | 1,353 | 35,996 | 5,622 | 4,267 | 4,742 | 4,002 | 17,364 | 5,424 |

| Male | 2,693 | 4,544 | 4,009 | 3,829 | 2,504 | 702 | 18,281 | 2,994 | 2,246 | 2,249 | 1,844 | 8,948 | 2,910 | |

| Female | 2,170 | 4,288 | 4,049 | 4,005 | 2,552 | 651 | 17,715 | 2,627 | 2,021 | 2,493 | 2,158 | 8,416 | 2,514 | |

| II(b,c,e) Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Both | 6,654 | 6,888 | 4,353 | 2,908 | 1,759 | 1,146 | 23,708 | 4,949 | 4,190 | 3,446 | 2,837 | 8,285 | 3,441 |

| Male | 4,405 | 4,445 | 3,060 | 1,852 | 937 | 672 | 15,371 | 3,071 | 2,637 | 2,410 | 2,018 | 5,235 | 1,865 | |

| Female | 2,249 | 2,443 | 1,293 | 1,056 | 822 | 474 | 8,337 | 1,879 | 1,553 | 1,036 | 818 | 3,050 | 1,576 | |

| Brain/central nervous system (III) | Both | 20,913 | 15,272 | 9,006 | 8,615 | 5,044 | 1,690 | 60,540 | 10,660 | 9,349 | 8,185 | 7,230 | 25,116 | 10,996 |

| Male | 11,275 | 8,482 | 4,792 | 4,318 | 2,269 | 751 | 31,887 | 5,586 | 5,114 | 4,428 | 4,009 | 12,750 | 5,011 | |

| Female | 9,638 | 6,790 | 4,214 | 4,297 | 2,775 | 939 | 28,653 | 5,074 | 4,235 | 3,757 | 3,221 | 12,366 | 5,985 | |

| IV Neuroblastoma & other peripheral nervous cell tumor | Both | 9,632 | 3,883 | 2,119 | 1,741 | 1,446 | 830 | 19,651 | 3,096 | 2,971 | 2,222 | 2,464 | 8,899 | 3,991 |

| Male | 4,936 | 2,015 | 988 | 588 | 438 | 216 | 9,181 | 1,655 | 1,485 | 1,095 | 1,222 | 3,724 | 1,252 | |

| Female | 4,696 | 1,868 | 1,131 | 1,153 | 1,008 | 614 | 10,470 | 1,441 | 1,486 | 1,127 | 1,241 | 5,176 | 2,739 | |

| VI Renal tumors | Both | 7,787 | 4,702 | 3,809 | 4,280 | 2,554 | 858 | 23,990 | 2,439 | 2,336 | 2,711 | 2,610 | 13,894 | 7,904 |

| Male | 3,862 | 2,174 | 1,729 | 2,403 | 1,379 | 500 | 12,047 | 1,158 | 1,137 | 1,276 | 1,352 | 7,124 | 4,473 | |

| Female | 3,925 | 2,528 | 2,080 | 1,877 | 1,175 | 358 | 11,943 | 1,282 | 1,199 | 1,434 | 1,257 | 6,771 | 3,431 | |

| VIII Malignant bone tumors | Both | 3,567 | 4,417 | 3,167 | 2,568 | 2,417 | 907 | 17,043 | 3,110 | 2,421 | 1,871 | 2,051 | 7,591 | 3,570 |

| Male | 2,066 | 2,569 | 1,787 | 1,290 | 1,053 | 472 | 9,237 | 1,986 | 1,208 | 1,259 | 1,089 | 3,695 | 1,645 | |

| Female | 1,501 | 1,848 | 1,380 | 1,278 | 1,364 | 435 | 7,806 | 1,123 | 1,213 | 612 | 962 | 3,896 | 1,925 | |

| VIII(a) Osteosarcoma | Both | 1,859 | 2,253 | 1,777 | 1,293 | 1,237 | 829 | 9,248 | 1,594 | 1,292 | 1,039 | 1,001 | 4,323 | 2,123 |

| Male | 1,002 | 1,265 | 1,014 | 657 | 499 | 396 | 4,833 | 965 | 601 | 685 | 495 | 2,087 | 965 | |

| Female | 857 | 988 | 763 | 636 | 738 | 433 | 4,415 | 629 | 690 | 354 | 506 | 2,235 | 1,158 | |

| VIII(c) Ewing tumor & related sarcomas of bone | Both | 1,347 | 1,467 | 972 | 728 | 358 | 148 | 5,020 | 1,146 | 772 | 599 | 721 | 1,781 | 600 |

| Male | 819 | 872 | 487 | 336 | 197 | 43 | 2,754 | 747 | 387 | 436 | 386 | 798 | 248 | |

| Female | 528 | 595 | 485 | 392 | 161 | 105 | 2,266 | 399 | 385 | 163 | 335 | 983 | 352 | |

| IX Soft tissue & other extraosseous sarcomas | Both | 6,799 | 7,126 | 4,166 | 4,913 | 4,267 | 4,670 | 31,941 | 4,270 | 3,518 | 3,404 | 2,645 | 18,105 | 10,464 |

| Male | 3,724 | 3,812 | 2,131 | 2,424 | 1,995 | 2,608 | 16,694 | 2,225 | 2,005 | 1,755 | 1,401 | 9,309 | 5,344 | |

| Female | 3,075 | 3,314 | 2,035 | 2,489 | 2,272 | 2,062 | 15,247 | 2,045 | 1,513 | 1,649 | 1,244 | 8,796 | 5,120 | |

| X Germ cell & trophoblastic tumors & neoplasms of gonads | Both | 5,233 | 7,869 | 5,634 | 6,245 | 6,641 | 6,817 | 38,439 | 4,760 | 4,359 | 3,557 | 3,503 | 22,260 | 13,953 |

| Male | 2,749 | 5,143 | 3,461 | 3,322 | 3,301 | 3,136 | 21,112 | 2,985 | 2,822 | 2,236 | 2,086 | 10,983 | 6,605 | |

| Female | 2,484 | 2,726 | 2,173 | 2,923 | 3,340 | 3,681 | 17,327 | 1,775 | 1,536 | 1,321 | 1,417 | 11,277 | 7,348 | |

Representativeness of CCSS

CCSS participants were similar in terms of age at diagnosis, gender, race and cancer type by time interval since diagnosis (see Table 3) to those reported in SEER, indicating CCSS was representative of the larger U.S. population of childhood cancer survivors to which the burden of morbidity data were extrapolated.

Table 3. Demographic and Disease Characterstics of the CCSS sample Compared to U.S. Survivors* Diagnosed with Childhood Cancers Estimates by Time Since Diagnosis.

| Times since diagnosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 to 14 | 15 to 24 | 25 to36 | ||||

| Characteristic | CCSS† (N=13,974) | US Population* (N=81,470) | CCSS† (N=12,031) | US Population* (N=62,741) | CCSS† (N=6,466) | US Population* (N=) |

| Age at Primary Diagnosis (n, %) | ||||||

| 0-4 | 5,738 (41%) | 29,298 (36%) | 5,031 (42%) | 23,963 (38%) | 2,586 (40%) | 15,286 (36%) |

| 5-9 | 3,175 (23%) | 16,767 (21%) | 2,694 (22%) | 13,033 (21%) | 1,470 (23%) | 9,021 (21%) |

| 10-14 | 2,877 (21%) | 16,819 (21%) | 2,460 (20%) | 11,429 (18%) | 1,349 (21%) | 8,779 (21%) |

| 15-19 | 2,184 (16%) | 18,586 (23%) | 1,846 (15%) | 14,316 (23%) | 1,061 (16%) | 9,115 (22%) |

| Gender (n, %) | ||||||

| Male | 7,514 (54%) | 44,617 (55%) | 6,339 (53%) | 34,089 (54%) | 3,354 (52%) | 21,892 (52%) |

| Female | 6,460 (46%) | 36,853 (45%) | 5,692 (47%) | 28,651 (46%) | 3,112 (48%) | 20,309 (48%) |

| Race (n, %) | ||||||

| White/Unknown | 12,392 (89%) | 69,021 (85%) | 10,770 (89%) | 53,819 (86%) | 5,948 (92%) | 37,686 (89%) |

| Black | 739 (5%) | 8,731 (11%) | 587 (5%) | 6,348 (10%) | 218 (4%) | 3,288 98%) |

| Other | 843 (6%) | 3,719 (5%) | 674 (6%) | 2,574 (4%) | 300 (5%) | 1,226 (3%) |

| Cancer Type (n, %) | ||||||

| Leukemia | 4,808 (34%) | 25,854 (32%) | 4,084 (34%) | 18,390 (29%) | 2,115 (33%) | 11,460 (27%) |

| Brain and central nervous system tumor | 1,761 (13%) | 17,538 (22%) | 1,441 (12%) | 13,243 (21%) | 692 (11%) | 7,493 (18%) |

| Hodgkin lymphomas (IIa) | 1,779 (13%) | 9,009 (11%) | 1,553 (13%) | 8,058 913%) | 910 (14%) | 6,289 (15%) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (IIa) | 1,059 (8%) | 7,634 (9%) | 925 (8%) | 5,269 (8%) | 503 (8%) | 3,329 (8%) |

| Renal tumors (VI) | 1,255 (9%) | 5,047 (6%) | 1,145 (10%) | 4,826 (8%) | 598 (9%) | 3,740 (9%) |

| Neuroblastoma | 953 (7%) | 5,174 (6%) | 863 (7%) | 4,247 (7%) | 474 (7%) | 3,120 (7%) |

| Soft tissue | 1,211 (9%) | 6,921 (8%) | 1,055 (9%) | 5,164 (8%) | 617 (10%) | 4,583 (11%) |

| Bone tumors (VIII) | 1,148 (8%) | 4,294 (5%) | 965 (8%) | 3,543 (6%) | 557 (9%) | 2,187 (5%) |

US survivors are estimated using the prevalence proportions of people diagnosed with cancer between 1975 and 2010 and ages 0 and 19 in the SEER-9 areas and applied to the respective US population to generate US counts.

Estimated Burden of Morbidity

Table 4 displays estimates of the number of prevalent cases for each morbidity indicator by age and time since diagnosis.

Table 4. Estimates of the Number of Prevalent Cases of Chronic Conditions, Cognitive Dysfunction and Compromised HRQOL and Health Status in Childhood Cancer Survivors in the U.S. who Survived a Minimum of 5 years as of January 1, 2011.

| Number of Prevalent Cases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years Since Diagnosis | |||||

| Chronic Conditions | Current Age | Total | 5 to 14 (n=105, 697) | 15 to 24 (n=81,519) | 25 to 36 (n=55,996) |

| Any Grade 1-4 Condition | 5-19 (n=61,882) | 41,059 (66%) | 35,208 | 5,851 | N/A |

| 20-29 (n=84,589) | 60,392 (71%) | 30,406 | 25,592 | 4,394 | |

| 30-39 (n=61, 461) | 48,796 (79%) | 5,822 | 24,891 | 18,083 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 30,986 (88%) | N/A1 | 6,122 | 24,867 | |

| Total (n=243,212) | 181,236 (75%) | 71,436 (68%) | 62,456 (77%) | 47,344 (85%) | |

| Any Grade 1-2 (mild/moderate) Condition | 5-19 (n=61,882) | 38,401 (62%) | 32,780 | 5,621 | N/A |

| 20-29 (n=84,589) | 55,297 (66%) | 27,644 | 24,087 | 4,196 | |

| 30-39 (n=61, 461) | 45,753 (74%) | 5,271 | 23,303 | 17,179 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 29,542 (84%) | N/A | 5,778 | 23,764 | |

| Total (n=243,212) | 169,263 (70%) | 65,695 (62%) | 58,789 (72%) | 45,139 (81%) | |

| Any Grade 3-4 (severe/life threatening or disabling) Condition | 5-19 (n=61,882) | 16,152 (26%) | 13,787 | 2,365 | N/A |

| 20-29 (n=84,589) | 24,492 (29%) | 12,109 | 10,572 | 1,811 | |

| 30-39 (n=61, 461) | 22,331 (36%) | 2,565 | 11,434 | 8,332 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 16,902 (48%) | N/A | 3,315 | 13,587 | |

| Total (n=243,212) | 79,877 (33%) | 28,461 (27%) | 27,686 (34%) | 23,730 (42%) | |

| Multiple chronic health conditions | |||||

| ≥2 Grade 3-4 | 5-19 (n=61,882) | 4,528 (7%) | 3,753 | 775 | N/A |

| 20-29 (n=84,589) | 7,090 (8%) | 3,150 | 3,319 | 621 | |

| 30-39 (n=61, 461) | 7,585 (12%) | 711 | 3,827 | 3,047 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 7,057 (20%) | N/A | 1,291 | 5,766 | |

| Total (n=243,212) | 26,260 (11%) | 7,614 (7%) | 9,212 (11%) | 9,434 (17%) | |

| ≥ 3 Grade 3-4 | 5-19 (n=61,882) | 1,511 (2%) | 1212 | 299 | N/A |

| 20-29 (n=84,589) | 2,296 (3%) | 911 | 1,148 | 237 | |

| 30-39 (n=61, 461) | 2,635 (4%) | 200 | 1,296 | 1,139 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 2,939 (8%) | N/A | 495 | 2,444 | |

| Total (n=243,212) | 9,381 (4%) | 2,323 (2%) | 3,238 (4%) | 3,820 (7%) | |

| Years Since Diagnosis | |||||

| Current Age | Total | 5 to 14 (None) | 15 to 24 (n=73,281) | 25 to 36 (n=55,996) | |

| Impaired Neurocognitive Functioning | 20-29 (n=40,353) | 15,946 (40%) | N/A2 | 13,522 | 2,424 |

| 30-39 (n=53,644) | 18,399 (34%) | N/A | 10,383 | 8,016 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 11,518 (33%) | N/A | 2,137 | 9,381 | |

| Total (n=129,277) | 45,863 (35%) | N/A | 26,042 (36%) | 19,821 (35%) | |

| HRQOL | |||||

| Physical Component Score | 20-29 (n=40,353) | 4,231 (10%) | N/A | 3,626 | 605 |

| 30-39 (n=53,644) | 8,788 (16%) | N/A | 5,134 | 3,654 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 8,220 (23%) | N/A | 1,636 | 6,584 | |

| Total (n=129,277) | 21,239 (16%) | N/A | 10,396 (14%) | 10,843 (19%) | |

| Mental Component Score | 20-29 (n=40,353) | 7,956 (20%) | N/A | 6,790 | 1,166 |

| 30-39 (n=53,644) | 9,897 (18%) | N/A | 5,708 | 4,189 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 5,691 (16%) | N/A | 1,103 | 4,588 | |

| Total (n=129,277) | 23,544 (18%) | N/A | 13,601 (19%) | 9,943 (18%) | |

| Years Since Diagnosis | |||||

| Current Age | Total | 5 to 14 (n=52,053) | 15 to 24 (n=73,281) | 25 to 36 (n=55996) | |

| Health Status Indicators | |||||

| Poor/Fair General Health | 20-29 (n=84,589) | 9,388 (11%) | 4,685 | 4,007 | 696 |

| 30-39 (n=61,461) | 8,310 (14%) | 961 | 4,222 | 3,127 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 5,973 (17%) | N/A | 1,152 | 4,821 | |

| Total (n= 181,330) | 23,671 (13%) | 5,646 (11%) | 9,381 (13%) | 8,644 (15%) | |

| Impaired Mental Health | 20-29 (n=84,589) | 14,965 (18%) | 7,969 | 6,125 | 871 |

| 30-39 (n=61,461) | 10,639 (17%) | 1,445 | 5,719 | 3,475 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 5,701 (16%) | N/A | 1,284 | 4,417 | |

| Total (n= 181,330) | 31,305 (17%) | 9,414 (18%) | 13,128 (18%) | 8,763 (16%) | |

| Functional Impairment | 20-29 (n=84,589) | 10,612 (13%) | 5071 | 4,617 | 924 |

| 30-39 (n=61,461) | 8,018 (13%) | 825 | 3,874 | 3,319 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 6,030 (17%) | N/A | 1,036 | 4,994 | |

| Total (n= 181,330) | 24,660 (14%) | 5,896 (11%) | 9,527 (13%) | 9,237 (16%) | |

| Limitations in Activity | 20-29 (n=84,589) | 10,182 (12%) | 5369 | 4,066 | 747 |

| 30-39 (n=61,461) | 8,802 (14%) | 1106 | 4,318 | 3,378 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 7,249 (21%) | N/A | 1,343 | 5,906 | |

| Total (n= 181,330) | 26,233 (14%) | 6,475 (12%) | 9,727 (13%) | 10,031 (18%) | |

| Pain (moderate to excruciating) | 20-29 (n=84,589) | 8,149 (10%) | 4,672 | 3,009 | 468 |

| 30-39 (n=61,461) | 7,533 (12%) | 1,147 | 3,834 | 2,552 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 5,336 (15%) | N/A | 1,117 | 4,219 | |

| Total (n= 181,330) | 21,018 (12%) | 5,819 (11%) | 7,960 (11%) | 7,239 (13%) | |

| Anxiety/Fear (medium to extreme) | 20-29 (n=84,589) | 10,807 (13%) | 6,027 | 4,134 | 646 |

| 30-39 (n=61,461) | 8,080 (13%) | 1,171 | 4,143 | 2,766 | |

| 40-49 (n=35,280) | 4,773 (14%) | N/A | 998 | 3,775 | |

| Total (n= 181,330) | 23,660 (13%) | 7,198 (14%) | 9,275 (13%) | 7,187 (13%) | |

N/A All participants were diagnosed between 1970-1986 at ages 0-19. Therefore, participants age 40 or older at completion of the questionnaires were at least 15 years post-diagnosis (earliest questionnaire November 1992);

N/A estimates for impaired neurocognitive dysfunction and HRQOL do not include survivors 5-14 years post diagnosis because at data collection (see Table 1), all participants in this category were at least 15 years post- diagnosis.

Chronic Conditions

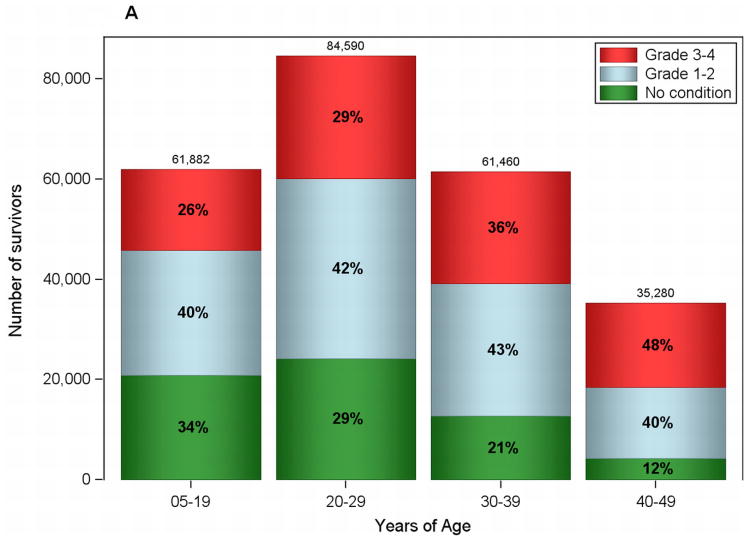

Approximately 70% of childhood cancer survivors were estimated to have a grade 1 or 2 (mild/moderate) chronic condition and about one-third (32%) were estimated to have a grade 3 or 4 (severe, disabling, or life-threatening) chronic condition. An estimated two-thirds (68%) of childhood cancer survivors had any chronic condition 5-14 years post-diagnosis with this number increasing to 77% and 85% at 15-24 and 25-36 years post-diagnosis, respectively. Two-thirds (66%) of childhood cancer survivors aged 5-19 years were projected to have any chronic condition (grade 1-4; see Figure 1). This proportion increased with increasing age to 88% at ages 40-49 (see Figure 1) reflecting the consistent increase in the proportion of survivors with a grade 3 or 4 condition across age categories. Almost half (48%) of those 40-49 had a grade 3 or 4 chronic condition. An estimated 11% of survivors had two or more grade 3 or 4 conditions, over half of which (55%) occur in those aged 30-49. Finally, an estimated 4% of childhood cancer survivors had three or more grade 3 or 4 chronic conditions with just over half (57%) observed in those aged 30-49.

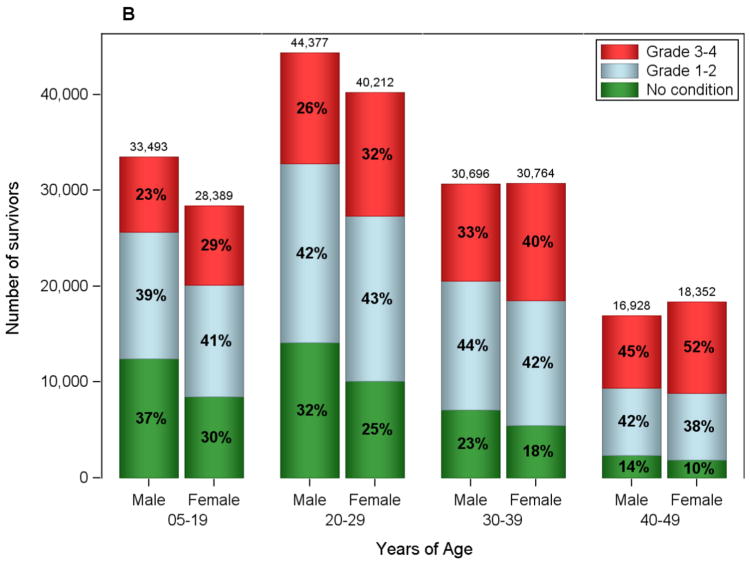

Figure 1.

A. Estimates of the Prevalence of chronic health conditions in Childhood Cancer Survivors in the U.S. who Survived a Minimum of 5 years as of January 1, 2011 by Age.

B. Estimates of the Prevalence of Chronic Conditions in Childhood Cancer Survivors in the U.S. who Survived a Minimum of 5 years as of January 1, 2011 by Gender and Age.

Grade 1 or 2 conditions prevalence estimates were similar for males and females across age categories ranging from 38-44% (see Figure 1). Grade 3 and 4 conditions increased for both males and females with increasing age, but the proportion of women in each age category wais higher (p-value<.001).

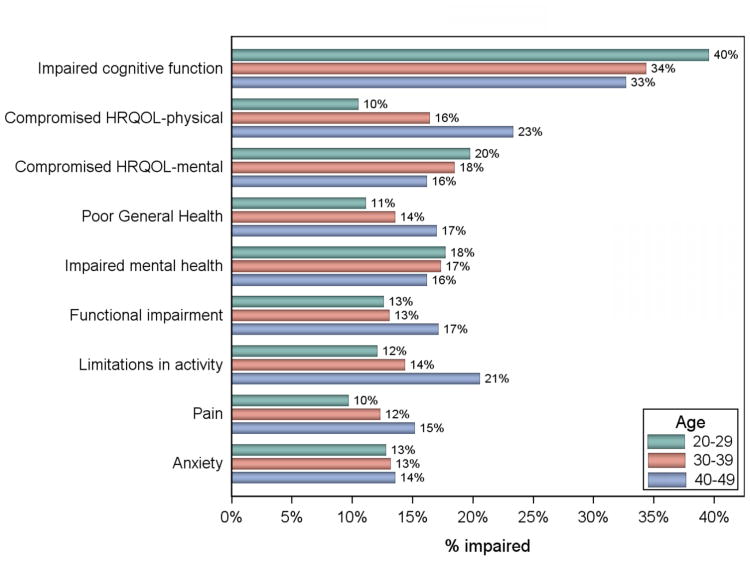

Neurocognitive Functioning

An estimated 35% of childhood cancer survivors ages 20-49 had neurocognitive dysfunction. The estimated number of prevalent cases decreased by age category ranging from 40-33% (see Figure 2) and was stable by time since diagnosis (36% and 35% at 15-24 and 25-36 years post-diagnosis, respectively).

Figure 2. Estimates of the Prevalence of Neurocognitive Dysfunction and Compromised HRQOL and Health Status in Childhood Cancer Survivors in the U.S. who Survived a Minimum of 5 years by Age as of January 1, 2011.

HRQOL

Estimated prevalence for compromised physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) HRQOL scores in survivors 20-49 years of age was 16% and 18%, respectively. The proportion of prevalent cases with compromised PCS scores increased across time since diagnosis and age categories from 10-23% (see Figure 2) and 10-23%, respectively. The proportion of survivors with MCS scores indicative of emotional problems was relatively consistent by time since diagnosis (18-19%) and age category (16-20%). In contrast to PCS, the prevalence of reduced MCS declined with increasing age (see Figure 2).

Health status

Prevalence estimates for self-reported poor or fair health (13%), functional impairment (14%), activity limitations (14%), impaired mental health (17%), pain (12%) and anxiety/fear (13%) were similar for childhood cancer survivors ages 20-49. The proportion of prevalent cases for impaired overall health status, activity limitations and pain increased by age ranging from 11-17%, 12-21% and 10-15%, respectively (see Figure 2), and remained stable by time since diagnosis. Impaired mental health and anxiety estimates remained stable by age. Anxiety estimates remained stable by time since diagnosis interval while impaired mental health estimates remained stable up to 24 years post-diagnosis and then declined at 25-36 years post-diagnosis (18% v. 14%). Finally, functional impairment prevalence estimates remained stable for survivors <40 years of age (13%) and increased for those 40-49 (17%), and increased by time since diagnosis interval from 11% to 16%.

Discussion

It is estimated that there were 388,501 childhood cancer survivors alive in the U.S. as of January 1, 2011, an increase of 59,849 from the previous (2005) estimate [20]. Findings of this analysis indicate that 83.5% of those diagnosed with childhood cancer survived ≥ 5 years after their cancer diagnosis, with almost 45% surviving ≥ 20 years. Moreover, 5% of childhood cancer survivors were ≥60 years of age. The increased prevalence of childhood cancer survivors through 2011 reflects ongoing treatment successes for a variety of childhood cancers. Moreover, by applying rates for selected adverse outcomes obtained from the CCSS cohort, we present the first population-level estimates of the number of survivors experiencing morbidity.

Our results further define the magnitude of the health challenges faced by childhood cancer survivors. Over two-thirds of survivors exhibited at least one chronic health condition 5-14 years post-diagnosis with almost half of survivors aged 40-49 estimated to have a severe or life-threatening chronic condition. Following a similar trajectory, though with lower prevalence, population estimates suggest a significant plurality of childhood cancer survivors experiencing compromised physical HRQOL, poor or fair overall health, functional impairments, activity limitation and pain. In contrast, emotional distress and anxiety prevalence remained relatively stable by age and time since diagnosis, while mental HRQOL and neurocognitive dysfunction demonstrated somewhat lower prevalence by age. From these projected trends, we begin to see the burden of morbidity faced by these survivors generally increased as they age and move further from time of diagnosis, a trend recently described by the CCSS [26].

Implications of Findings

Harkening back to earlier warnings [27], a clear message emerges from these findings: a singular focus on curing cancer yields an incomplete picture of childhood cancer survivorship. The burden of chronic conditions in this population is profound, both in occurrence and severity. Due to their young age at diagnosis and their longevity, the consequences of these morbidities have implications for both survivors and the health care system. Survivors are likely challenged by the demand of managing multiple chronic conditions and the resulting limitations in their daily life, especially in the context of potential lack of awareness of their long-term health risks [28]. These limitations in physical, cognitive and mental functioning can disrupt typical development of personal relationships, education, and occupation, establishing independence, and negotiating family demands. Facing typical developmental milestones in the context of managing multiple morbidities is a challenge for which limited personal and health care system resource and support may exist. Childhood cancer survivors may also face challenges in their interactions with the health care system [3] as they may represent high service users requiring the management of multiple teams of specialists, appointments, medication regimens, and financial outlays. Typical population guidelines for preventive behaviors such as cancer screening may not apply to this group [29], further complicating clinical pathways of care. Moreover, the complex morbidity in these survivors challenges health care system communication, cost, and care coordination processes.

Given the emerging picture of significant chronic condition burden for these childhood cancer survivors occurring within the context of functional and cognitive limitations as well as psychosocial distress for a significant subset, the resulting challenges form the basis of key directions for suggested research.

Susceptibility to Multiple Chronic Conditions

Essential to improving our understanding of morbidity susceptibility is the question: What factors are associated with increased susceptibility? This question calls for examination from multiple perspectives in addition to oncology including genomics, personalized medicine, treatment regimen specific toxicities, behavioral medicine, psychology, cardiology and endocrinology. A related question is the extent and mechanisms by which cancer treatments interact with the natural aging process. While the high morbidity prevalence suggests childhood survivors' functional age may be older than their chronological age suggests [3], elucidating potential mechanisms underlying these processes is an important next step. Additionally, further explication of morbidity trajectories, and determinants of these trajectories, is necessary. However, it is important to move beyond the description of a single chronic comorbidity (e.g., cardiac), and construct a picture of parallel and interactive trajectories, given our findings suggest older survivors may be experiencing multiple, serious chronic conditions and limitations.

Broadening the scope beyond chronic conditions to include other morbidity indicators (i.e., HRQOL, health status and neurocognitive functioning), the question of susceptibility remains vital. What biomarkers or mechanistic processes are associated with decrements in cognitive functioning and health status? What are the susceptibilities for the consistent subset of patients experiencing impaired mental health? How do physical and psychological factors interact to influence morbidity burden? Answering these questions could result in improved care via risk stratification and intervention development, but will require detailed longitudinal assessments to understand the pathophysiology of outcome-specific conditions.

Prevention of Chronic Diseases Morbidity

Our data illustrate an increased prevalence of poor health status including functional impairment and activity limitations in those aged 40-49. Approaches focused on preventing and ameliorating this health trajectory are essential. For example, physical activity, weight management, social support, and cognitive stimulation have been shown to be key components of healthy aging across disease prevention and management, cognition, and quality of life domains [30]. Understanding the role of these factors in the prevention and trajectories of development of morbidity in childhood cancer survivors is essential. Current childhood cancer survivor screening guidelines recommend screening for second cancer and chronic conditions [29]. However, these guidelines will need to be updated as cancer survivors age and could be expanded to include the additional endpoints explored in this study. Lastly, multiple studies have cited age-associated declines in cognitive abilities as a concern in the general population [31]. Since approximately one-third of childhood cancer survivors ≥ 15 years beyond diagnosis are estimated to experience neurocognitive dysfunction, investigation into possible prophylactic strategies and interventions warrants further investigation.

Care Coordination

Childhood cancer survivors need comprehensive follow-up care to address their complex healthcare needs [32, 33]. Their needs do not end with cancer treatment. The burden of managing multiple chronic conditions and the accompanying need to coordinate care between multiple professionals and care teams becomes even more complicated for childhood cancer survivors and the health care system with the added need for incorporation of risk-based survivorship care. The emerging focus on survivorship care planning is in direct response to growing appreciation of the multiple chronic and late effects of cancer experienced by both childhood and adult cancer survivor populations and their care coordination needs [34-36]. Much emphasis has been placed on documentation of treatments and toxicities, the transmission of screening schedules and information on health behaviors. While documentation of this information is important, it is imperative to move to more active survivorship care planning and coordination to simultaneously address the prevalence of chronic conditions, impairments and limitations presented here, and the dynamic, complex active prevention and treatment necessary for childhood cancer survivors.

Rehabilitation Model Focused on Integrated Care

Determining the most effective and efficient clinical models of care for this population is an important next step [3, 37]. Conceptualizing survivorship care through a rehabilitation model focused on optimization of function and quality of life and the coordination of complex care [38] offers rich opportunities for determining how best to address morbidity burden across the childhood cancer survivorship trajectory, especially since the significant chronic condition burden may be further complicated by compromised mental health and physical and cognitive dysfunction. Future research is needed to determine the feasibility and efficacy of this approach to address childhood cancer survivors' needs.

Limitations

While study strengths include the use of multiple indicators of morbidity burden and extrapolation of these data to obtain population-level prevalence estimates, it is not without limitations. First, because the granularity and reliability of SEER data is limited in terms of secondary treatment and specific treatment agents and dosages, we were not able to directly link our findings to treatment data. Thus, we assumed treatment for childhood cancers was similar for the 1970-1986 CCSS treatment era as for the 1975-2005 diagnosis era used for SEER and are unable to comment on how these outcomes may differ based on treatment received. Most of our morbidity burden measures were based on self-report and thus are subject to possible under- and over-reporting. Our estimates of morbidity prevalence included only those who survived a minimum of 5 years and a maximum of 36 years and do not represent all childhood survivors. Future research is warranted to explore these relationships further by treatment and varying times since diagnosis to obtain a richer, more accurate picture of the burden of morbidity in this population and provide further insight into how morbidity may be prevented or delayed.

Conclusions and Impact

The estimated prevalence of childhood cancer survivors is increasing, as is the estimated morbidity prevalence in those ≥ 5 years beyond diagnosis. Taken together, these data paint a picture of a population experiencing co-occurring treatment benefits and morbidity. These findings call for future research focused not only on decreasing the morbidity burden, but also incorporating effective clinical models of care coordination and rehabilitation to reduce morbidity burden and optimize childhood cancer survivors' HRQOL, physical and neurocognitive functioning and mental health.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study is supported by a grant (U24-CA-55727; GA, Principal Investigator) from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, et al., editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2011. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/, based on November 2013 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM, Landier W. Survivorship: Childhood cancer survivors. Prim Care. 2009;36:743–780. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robison LL, Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: Life-long risks and responsibilities. Nature Rev Cancer. 2014;14:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, Mulrooney DA, Chemaitilly W, Krull KR, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood canceroutcomes among adult survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309:2371–2381. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowling E, Yabroff KR, Mariotto A, McNeel T, Zeruto C, Buckman D. Burden of illness in adult survivors of childhood cancers. Cancer. 2010;116:3712–3721. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman MC, Mulrooney DA, Steinberger J, Lee J, Baker KS, Ness KK. Deficits in physical function among young childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2799–2805. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.8081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Lorenzi MF, Goddard K, Spinelli JJ, Gotay C, McBride ML. Late morbidity leading to hospitalization among 5-year survivors of young adult cancer: A report of the childhood, adolescent and young adult cancer survivors research program. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:1174–1182. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurt BA, Nolan VG, Ness KK, Neglia JP, Tersak JM, Hudson MM, et al. Hospitalization rates among survivors of childhood cancer in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:126–132. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ness KK, Krull KR, Jones KE, Mulrooney DA, Armstrong GT, Green DM, et al. Physiologic frailty as a sign of accelerated aging among adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4496–4503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeltzer LK, Recklitis C, Buchbinder D, Zebrack B, Casillas J, Tsao JC, et al. Psychological status in childhood cancer survivors: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2396–2404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadan-Lottick NS, Zeltzer LK, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Ellenberg L, Gioia G, et al. Neurocognitive functioning in adult survivors of childhood non-central nervous system cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:881–893. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tai E, Buchanan N, Townsend J, Fairley T, Moore A, Richardson LC. Health status of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118:4884–4891. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, Breslow NE, Donaldson SS, Green DM, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38:229–239. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, Chow EJ, Davies SM, Donaldson SS, et al. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A national cancer institute–supported resource for outcome and intervention research. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2308–2318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leisenring WM, Mertens AC, Armstrong GT, Stovall MA, Neglia JP, Lanctot JQ, et al. Pediatric cancer survivorship research: Experience of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2319–2327. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Surveillance Epidemiology End Results(SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) Research Data (1973-2011),National Cancer Institute DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch, released April 2014 based on the November 2013 submission

- 19.Ries LAG, Smith MA, Gurney JG, Linet M, Tamra T, Young JL, Bunin GR, editors. Cancer Incidence and Survival among Children and Adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975-1995. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 1999. SEER Program NIH Pub. No. 99-4649. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Scoppa S, Hachey M, Ries L, et al. Long-term survivors of childhood cancers in the united states. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1033–1040. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results(SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 9 Regs Research Data, Nov 2013 Sub (1973-2011) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969-2012 Counties Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch; released April 2014 based on the November 2013 submission. Availabe from:http://seer.cancer.gov/

- 22.Feldman AR, Kessler L, Myers MH, Naughton MD. The prevalence of cancer. Estimates based on the connecticut tumor registry. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1394–1397. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198611273152206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simonetti A, Gigli A, Capocaccia R, Mariotto A. Estimating complete prevalence of cancers diagnosed in childhood. Stat Med. 2008;27:990–1007. doi: 10.1002/sim.3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Hobbie W, Chen H, Gurney JG, et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA. 2003;290:1583–1592. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong GT, Kawashima T, Leisenring W, Stratton K, Stovall M, Hudson MM, et al. Aging and risk of severe, disabling, life-threatening, and fatal events in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1218–1227. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D'Angio GJ. Pediatric cancer in perspective: Cure is not enough. Cancer. 1975;35:866–870. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197503)35:3+<866::aid-cncr2820350703>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, Neglia JP, Yasui Y, Hayashi R, et al. Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2002;287:1832–1839. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.14.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, Forte KJ, Sweeney T, Hester AL, et al. Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: The children's oncology group long-term follow-up guidelines from the children's oncology group late effects committee and nursing discipline. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4979–4990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lara J, Godfrey A, Evans E, Heaven B, Brown LJ, Barron E, et al. Towards measurement of the healthy ageing phenotype in lifestyle-based intervention studies. Maturitas. 2013;76:189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krull KR, Bhojwani D, Conklin HM, Pei D, Cheng C, Reddick WE, et al. Genetic mediators of neurocognitive outcomes in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2182–2188. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.7944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Mahoney MC, et al. Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4401–4409. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM. Long-term complications following childhood and adolescent cancer: Foundations for providing risk-based health care for survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:208–236. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.4.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Institute of Medicine. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institure of Medicine Childhood cancer survivorship: Improving care and quality of life. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livestrong and Institute of Medicine. Identifying and addressing the needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oeffinger KC, Nathan PC, Kremer L. Challenges after curative treatment for childhood cancer and long-term follow up of survivors. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:251–273. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alfano CM, Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Hahn EE. Cancer survivorship and cancer rehabilitation: Revitalizing the link. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:904–906. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (ctcae), version 4.03. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krull KR, Gioia G, Ness KK, Ellenberg L, Recklitis C, Leisenring W, et al. Reliability and validity of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study neurocognitive questionnaire. Cancer. 2008;113:2188–2197. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ellenberg L, Liu Q, Gioia G, Yasui Y, Packer RJ, Mertens A, et al. Neurocognitive status in long-term survivors of childhood cns malignancies: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:705. doi: 10.1037/a0016674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993:247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]