Four fundamental principles drive public funding for family planning. First, unintended pregnancy is associated with negative health consequences, including reduced use of prenatal care, lower breast-feeding rates, and poor maternal and neonatal outcomes.1,2 Second, governments realize substantial cost savings by investing in family planning, which reduces the rate of unintended pregnancies and the costs of prenatal, delivery, postpartum, and infant care.3 Third, all Americans have the right to choose the timing and number of their children. And fourth, family planning enables women to attain their educational and career goals and families to provide for their children. These principles led to the bipartisan passage of Title X in 1970 and later to other federal- and state-funded programs supporting family planning services for low-income women.

Despite the demonstrated positive effects of these programs, political support and funding for them have begun to erode. Recently, efforts to expand access to contraception through the Affordable Care Act ignited a broad debate regarding the proper role of government in this sphere, and proposals have been put forth to eliminate Title X.

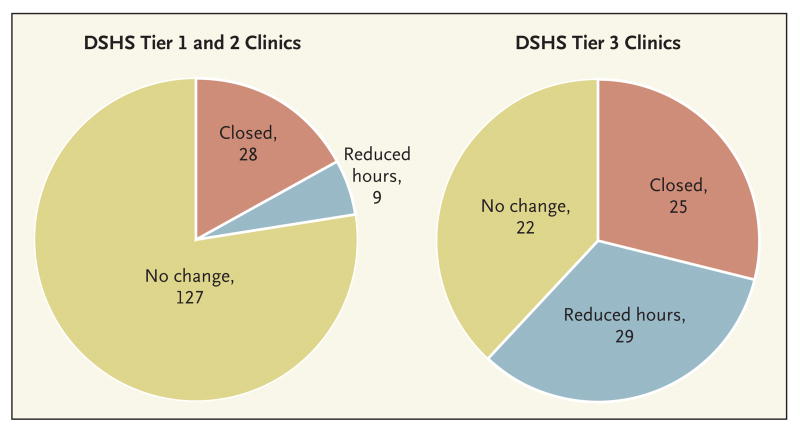

Several states have already taken substantial steps to reduce public funding for family planning and other reproductive health services. In 2011, Texas enacted the most radical legislation to date, cutting funding for family planning services by two thirds — from $111 million to $37.9 million for the 2-year period. The remaining funds were allocated through a three-tiered priority system, with organizations that provide comprehensive primary care taking precedence over those providing only family planning services (see pie charts). The Texas legislature also imposed new restrictions on abortion care and reauthorized the exclusion of organizations affiliated with abortion providers from participation in the state Medicaid waiver program, the Women's Health Program (WHP), which was due for renewal in January 2012. Although the exclusion had not previously been enforced by the state Health and Human Services Commission, it runs contrary to federal policy, and the renewal of the WHP was declined by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. In 2010, the WHP provided services to nearly 106,000 women 18 years of age or older with incomes below 185% of the federal poverty level who had been legal residents of Texas for at least 5 years. Almost half of these women were served at Planned Parenthood clinics.

To implement the legislation and funding cuts, the Texas Department of State Health Services reduced the number of funded family planning organizations from 76 to 41. Some of the largest organizations that continue to receive funding lost up to 75% of their budgets. The WHP remains in place as of mid-September 2012, because Planned Parenthood providers obtained a preliminary injunction order on April 30, 2012, against enforcement of the rule banning abortion provider affiliates. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that the order should be vacated, but it remains in effect pending the ruling on a petition for rehearing.

Texas has a very high teen birth rate, many undocumented migrants, and the second-largest number of Medicaid births (after California). For demographically and socioeconomically similar states, Texas's experience may be a harbinger of the broader impact of eliminating public funding for family planning.

As part of a comprehensive 3-year evaluation of the legislative changes to family planning policy in Texas, we have interviewed 56 leaders of organizations throughout the state that provided reproductive health services using Title X and other public funding before the cuts went into effect. From these interviews, we have identified the likely channels through which the legislation will influence reproductive outcomes and the women who are most likely to be affected.

Facing severe budget cuts, most clinics have restricted access to the most effective contraceptive methods because of their higher up-front costs.4 Even with the 340B drug-pricing program, which offers discounts of 50 to 80%, a clinic may pay $250 or more for an intrauterine device (IUD) or subdermal implant, whereas a pack of pills costs about $5. To continue serving as many clients as possible, clinics now rarely offer IUDs or implants, reserving these methods for women with medical contraindications to other contraceptives. Some providers have started waiting lists for IUDs and implants in the unlikely event that they can purchase them with money left over at the end of a funding period. In addition, as more women are steered toward contraceptive pills, they are being provided with fewer pill packs per visit, a practice that has been shown to result in lower rates of continuation with the method and that may increase the likelihood of unintended pregnancy — and therefore that of abortion.5

Many organizations have also implemented or expanded systems that require clients to pay for services if they don’t qualify for the WHP. Though the fees for well-woman exams and a pack of pills are lower than in the private sector, they vary widely among clinics and within communities and remain out of reach for some of the poorest women. Those who cannot pay are turned away, whereas previously their visit would have been covered by public funds. The organizational leaders we spoke to reported that women who can pay the newly instated fees are choosing less-effective methods, purchasing fewer pill packs, and opting out of testing for sexually transmitted infections to save money.

The 35 organizations that lost all funding are facing two additional repercussions. They are no longer eligible to buy contraceptives through the 340B discount program and must pay higher prices, which are passed on to patients. And they are no longer exempt from Texas's law requiring parental consent for teens younger than 18 years of age who seek contraceptive services. Under a federal exemption to such state laws, providers receiving Title X funds are required to provide services to teens without parental consent. As a result of the cuts, teens seeking confidential services are already having to travel farther to obtain them.

Finally, there is considerable variation across Texas in terms of the willingness and ability of communities to cover the shortfall in public funding for family planning. In one community, the hospital-donated office space is a critical lifeline to a family planning clinic serving more clients with less public funding. In another community, the main public hospital is increasingly relying on the county's indigent care program and accumulating a deficit as it continues to provide care for all women in need. Planned Parenthood affiliates in more affluent communities have offset funding cuts with private donations, but that hasn’t been possible for affiliates in impoverished or politically conservative areas — and it's unclear how sustainable the fundraising will be even in the more affluent communities. In communities with a large population of migrants who are ineligible for the WHP, the challenge is even greater.

Ostensibly, the purpose of the law was to defund Planned Parenthood in an attempt to limit access to abortion, even though federal and state funding cannot be used for abortion care anyway. Instead, these policies are limiting women's access to a range of preventive reproductive health services and screenings. Disadvantaged women must choose between obtaining contraception and meeting other immediate economic needs. And, as one of our interviewees pointed out, providers are put in the position of “trying to decide, out of the most vulnerable, who is the most, most vulnerable.” Moreover, the impact of these policies is not limited to Planned Parenthood; other organizations have had to close clinics, reduce hours, and lay off dedicated, experienced staff members. We are witnessing the dismantling of a safety net that took decades to build and could not easily be recreated even if funding were restored soon.

Time will reveal the full effects of these budget cuts on the rates of unintended pregnancies and induced abortions and on state and federal health care costs. Already, the legislation has created circumstances that force clinics and women in Texas to make sacrifices that jeopardize reproductive health and well-being. This unfortunate situation does offer an opportunity to compare outcomes such as contraceptive use, unintended pregnancy, and abortion in Texas and other states, such as California, that have less restrictive family planning policies. Such comparisons could provide important information about the impact of these policies. Debates about funding in Congress and in other states should consider the results of such research and take a hard look at the implications for women, families, and communities of restricting access to contraception.

Effects on Clinics in Texas of Cuts in Family Planning Funding.

The Department of State Health Services (DSHS) Tier 1 clinics are public entities (e.g., health departments) that provide family planning services, Tier 2 clinics are nonpublic entities that provide family planning as part of comprehensive primary and preventive care, and Tier 3 clinics are nonpublic entities that provide family planning only. Although clinics in Tier 3 account for a smaller number of total sites, they served approximately 41% of women seeking publicly funded family planning services.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Mohllajee AP, Curtis KM, Morrow B, Marchbanks PA. Pregnancy intention and its relationship to birth and maternal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:678–86. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000255666.78427.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plann. 2008;39:18–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frost J, Finer LB, Tapales A. The impact of publicly funded family planning clinic services on unintended pregnancy and government cost savings. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19:778–96. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1998–2007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster DG, Hulett D, Bradsberry M, Darney P, Policar M. Number of oral contraceptive pill packages dispensed and subsequent unintended pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:566–72. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182056309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]