Abstract

While extensive research has examined associations between marriage, cohabitation, and the health of heterosexual adults, it remains unclear whether similar patterns of health are associated with same-sex partnerships for lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) older adults. This article examines whether having a same-sex partner is associated with general self-reported health and depressive symptoms for LGB older adults. Based on survey data collected from LGB adults 50 years of age and older, having a same-sex partner was associated with better self-reported health and fewer depressive symptoms when compared with single LGB older adults, controlling for gender, age, education, income, sexuality, and relationship duration. Relationship duration did not significantly impact the association between partnership status and health. In light of recent public debates and changes in policies regarding same-sex partnerships, more socially integrated relationship statuses appear to play a role in better health for LGB older adults.

An extensive body of scholarship has documented associations between being married or cohabitating and health (see Waite, 1995; Waite & Gallagher, 2000). Most of the research concerning health outcomes associated with marriage and cohabitation assumes that respondents are heterosexual and that couples are always comprised of opposite sex partners. Much less attention has been paid to possible associations between partnership status and health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) adults.

Many LGB older adults have been forming long-lasting, intimate same-sex partnerships for all of their adult lives. Although not legally recognized by any state in the United States prior to 1999 (Human Rights Campaign, 2012), same-sex partnerships have long provided LGB older adults opportunities to share material and emotional resources as well as social networks and direct social support. Within the context of ongoing stigma and public debates, same-sex partnerships enjoy far less universal social and legal sanction than heterosexual marriages (Saad, 2012). Despite an increasing number of states recently recognizing same-sex marriage, same-sex partnerships in most states have no legal standing, and the legal recognition of those married in one state affords little or no standing in most other states. While the option to cohabitate without marrying is generally available to all heterosexual partners, identifying as part of an unmarried same-sex partnership may reflect a deliberate choice or differential access to state-recognized same-sex partnerships for LGB individuals. Same-sex partnerships may provide similar health benefits as those observed in research on married and cohabiting heterosexuals, or they may be associated with distinct patterns of health.

Currently, it remains unclear whether older adults in same-sex partnerships experience benefits to physical and mental health relative to their single LGB peers. This article reviews the literature regarding health for partnered heterosexuals and LGB individuals and examines these associations in a national sample of LGB older adults. We conclude by considering implications of these findings for health care and future research to address the role that same-sex partnerships may play in supporting the health of LGB older adults and their communities.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS

Same-Sex Partnerships and Health

Researchers have amassed a large body of evidence, documenting that heterosexual adults experience positive health outcomes associated with being married and cohabiting (Waite, 1995; Gallagher & Waite, 2000; Ross, Mirowsky, & Goldsteen, 1990; Manzoli, Villari, Pirone, & Boccia, 2007). Mortality is lower for married and cohabiting adults when compared with single, divorced, and widowed peers (Hu & Goldman, 1990; Coombs, 1991; King & Reis, 2012; Idler, Boulifard, & Contrada, 2012; Blomgren, Martikainen, Grundy, & Koskinen, 2012). Married and cohabiting adults report better physical health (Prior & Hayes, 2003; Waldron, Hughes, & Brooks, 1996; Pienta, Hayward, & Jenkins, 2000; Coombs, 1991) and mental health (Williams, 2003; Simon, 2002; Frech & Williams, 2007; Sherbourne & Hayes, 1990; Coombs, 1991) when compared with unmarried adults living alone. Many researchers have shown that having an intimate partner, whether married or unmarried, is consistently accompanied by better health outcomes.

When looking specifically at older adults, researchers have similarly found better health associated with having a partner. Married and cohabiting older adults live longer than unmarried peers who live alone (Manzoli et al., 2007; Scafato et al., 2008; Tower, Stanislav, & Darefsky, 2002; Goldman, Korenman, & Weinstein, 1995). Marriage and cohabitation are associated with better physical health and functional ability among older adults (Goldman et al., 1995; Schoenborn & Heyman, 2009). Henderson, Scott, and Kay (1986) found that cohabiting older adults reported lower frequency of depressive symptoms. In contrast, Wu, Shimmele & Chappell (2012) reported that married and cohabiting older adults were significantly more likely to meet criteria for major depressive disorder than single, older adults. Most research, however, has found that married and cohabiting older adults fare better on multiple measures of physical and mental health than their single peers.

In contrast to the extensive literature on heterosexuals, the scholarship concerning the associations between health and same-sex partnerships is much more limited. There have been relatively few sources of data on same-sex partnerships, and research examining associations between partnership status and health among LGB older adults has had to rely on relatively small samples as compared to the extensive scholarship on heterosexuals, thus limiting their power to detect significant differences. A few studies report that having a same-sex partner is associated with measures of general health, depression, stress, and happiness when compared to single LGB adult peers in general (Wienke & Hill, 2009; Riggle, Rostosky & Horne, 2010; Wight, LeBlanc, de Vries, & Detels, 2012; Wight, LeBlanc, & Badgett, 2013; Grossman, D’Augelli, & O’Connell, 2001). Specifically among LGB older adults, those partnered report fewer depressive symptoms (Wight et al., 2012), less loneliness, and better general mental health than LGB older adults living alone (Grossman et al., 2001). The development of scholarship on same-sex partnerships and the health of LGB older adults is at an early stage of development, but initial evidence suggests that, like heterosexual older adults, they may experience health benefits from having an intimate partner.

Theory

Social Integration Theory proposes that identification with and participation in stable social structures reduce isolation, protect health, and regulate the health behaviors of individuals (Durkheim, 1951). Socially recognized roles, such as being married or partnered, provide purpose and meaning to life, which promote overall health and psychological well-being (Thoits, 1983; Kobrin & Hendershot, 1977). Socially endorsed family forms incorporate individuals into systems of support and mutual obligation that lead to conformity with priorities and behaviors that reduce health risks (Gove, 1972). Transitioning into social roles with greater symbolic commitment (e.g., from single to dating or dating to partnered) reflects more socially integrated relational ties along a hierarchy of statuses that increase psychological health and well-being for individuals (Dush & Amato, 2005).

Natale and Miller-Cribbs (2012) argue that there are hierarchies of relationship statuses for LGB adults today. Levels of social stigma and acceptance differentiate LGB relationship statuses. Marriages reflect the most socially integrated relationship status, followed by civil unions, domestic partnerships, designated beneficiaries, cohabiters, and singles. Both the social provision of these hierarchical statuses and the individual endorsement of available statuses reflect levels of social integration for LGB individuals. Consistent with Social Integration Theory, LGB adults identifying their relationship status with higher levels of social integration are expected to enjoy better psychological and physical health.

Relationship researchers have theorized that benefits of more socially integrated relationship statuses accrue over time, and in several studies relationship duration has been positively associated with better health outcomes (Meadows, 2009; DuPre & Meadows, 2007; Lillard & Waite, 1995; Gibb, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2011). Whether a similar cumulative advantage pertaining to relationship duration occurs for LGB older adults has yet to be examined.

Based on Social Integration Theory, the current study examines whether LGB older adults who identify as partnered or married experience better health when compared with single LGB older adults. We hypothesize that same-sex partnerships will be associated with better self-reported general health and fewer depressive symptoms than observed among single LGB older adults. Further, we hypothesize that the duration of same-sex partnerships will be positively associated with self-reported general health and fewer depressive symptoms.

METHODS

Data for this study came from the Caring and Aging with Pride Project (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011), which conducted a cross-sectional survey in collaboration with 11 community agencies that provide services to LGBT older adults. The agencies were located in the Northeast, Midwest, and west of the United States. Surveys were distributed using the agencies’ mailing lists to LGBT adults 50 years of age and older. Some of the agencies maintain only electronic mailing lists, and therefore a web-based version of the survey was also provided as an optional method of response. Agencies delivered an introductory explanation of the nature and purpose of the survey prior to its distribution, and informed consent was obtained by providing a summary of rights and potential risks and benefits to prospective respondents who received the survey.

Respondents answered questions pertaining to physical and mental health, life satisfaction, and background characteristics, including relationship status. Sixty-three percent (n = 2201) of all of the hardcopy surveys distributed were completed. Through the web-based option, an additional 359 electronic surveys were received. The project was unable to verify the number of potential respondents who could have completed the electronic version of the survey, and therefore the response rate for that portion of the surveys is unknown. Including the hardcopy and electronic versions, a total of 2,560 respondents completed the survey. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board approved all of the study procedures.

The Caring and Aging with Pride Project successfully collected responses from an unprecedented large sample of LGB and transgender older adults from across the United States, making this dataset particularly useful for studying within group differences among this small minority of the overall population. The sample included a diverse cross-section based on key demographic characteristics, including sufficient subsamples of bisexual older adults to examine both the effects of gender and the sexual orientation (same-sex and bisexual orientations). By including measures on a range of demographic and health variables, this data set presents an opportunity to examine associations between partnership status and the health of LGB older adults.

Consistent with the majority of research on LGB populations (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Muraco, 2010), “older adults” were defined as those 50 years of age and older. In order not to conflate the effects of gender identity and sexual orientation, this analysis excludes respondents who identified as transgender. Respondents who indicated their partnership status, relationship duration, race/ethnicity, education, annual household income, chronic illnesses, age, and gender were included, resulting in a sample of size of 2,150 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Adults, Aged 50-95 Years (N = 2173): Caring and Aging With Pride Project National Study

| Total | Unpartnered | Partnered/married | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2150 | N = 1200 | N = 950 | p-valuea | |

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Age (years) | 66.8 (9.0) | 67.8 (9.0) | 65.5 (8.8) | <0.001 |

| Relationship duration (years) | 8.9 (13.2) | – b | 20.1 (13.0) | – |

| Percent | ||||

| Female | 35.2 | 29.7 | 42.2 | <0.001 |

| White | 87.4 | 85.8 | 89.3 | 0.023 |

| Bisexual | 5.1 | 6.3 | 3.5 | 0.003 |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| High school or less | 7.7 | 9.7 | 5.2 | |

| <4 years college | 18.0 | 21.4 | 13.7 | |

| ≥4 years college | 74.3 | 68.9 | 81.2 | |

| Income | <0.001 | |||

| <$35,000 | 36.7 | 51.3 | 18.1 | |

| $35,000–$75,000 | 31.7 | 33.3 | 29.7 | |

| >$75,000 | 31.7 | 15.4 | 52.2 | |

| ≥5 Physical illnesses | 60.0 | 63.3 | 55.8 | <0.001 |

| Depression and/or anxiety | 36.7 | 40.8 | 31.5 | <0.001 |

Note. SD = standard deviation.

Based on t tests for difference of means and Pearson’s χ2 for proportions.

Respondents who reported not being in a current relationship but indicated a duration of their current relationship were recoded as 0 years.

Dependent Variables

A single question from the Medical Outcomes Health Survey (Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1994) assessed self-reported general health, with six response options ranging from “excellent” to “very poor.” Single-item measures of general self-reported health are used extensively in population research and have been found to provide reliable and comparable results across studies (Kempen, 1992; Thombs et al., 2008). The 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale-Short Form (CES-D-S; Andersen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994; Radloff, 1977) measured the estimated number of days respondents experienced depressive symptoms in the past week (<1 day, 1–2 days, 3–4 days, 5–7 days). Scores were summed across the 10 symptoms (summed range: 0–30), with higher scores indicating more frequently experienced depressive symptoms. Alpha reliability for the CES-D-S for this sample was 0.87.

Independent Variables

Respondents selected their current partnership status from six options (single, partnered, married, divorced, widowed, or separated). Responses were dichotomized to compare respondents currently in a same-sex partnership (identifying as married or partnered) with those not currently in a relationship (single, divorced, widowed, or separated). Those identifying their current status as partnered or married, were also asked to indicate how long they have been in the relationship. The variable “gender” included the option to identify as female or male.

Additional covariates assessed in this analysis included race (dichotomized as either White or not White) and sexual orientation (dichotomized as lesbian/gay or bisexual). Education was measured using a six-category variable, which was collapsed into three categories for the purpose of this analysis (high school or less, less than 4 years of college, or 4 or more years of college). Similarly, income was measured using a six-category variable, which was collapsed into three categories for the analysis (<$35,000, $35,000-$75,000, >$75,000). Chronic physical illnesses were assessed by asking respondents to indicate if they had ever been told by a doctor that they had any of 21 chronic health conditions (e.g., asthma), with responses dichotomized for this analysis (less than five physical illnesses or five or more). Chronic mental health, used as a covariate in examining general health, was assessed by asking respondents if they had ever been told by a doctor that they had depression or anxiety, with responses dichotomized (yes/no to depression and/or anxiety).

Analysis

Analyses were conducted using the statistical software Stata version 12. Initial analyses examined bivariate relationships between partnership status and the other independent variables. Preliminary tests for multicollinearity were used to determine that the independent variables were not collinear to any concerning degree. Dependent variables were analyzed for optimal model choice. Ordinal logistic regression was used to examine the six-category general health outcome. Based on the unit of measure and distribution of CES-D-S scores, negative binomial regression was employed to model the count of depressive symptoms. For all analyses, a 0.05 confidence level was chosen a priori to indicate a significant statistical association.

RESULTS

Table 1 describes the sample. The average age of respondents was 66.8 years (range: 50–95). Within the sample, 44.2% identified as married or partnered, and married and partnered respondents reported being in their current relationship on average 8.9 years (range: 0–65 years). The majority of respondents were male (64.8%), White (87.4%), and same-sex oriented (94.9%). Most respondents had completed at least 4 years of college (74.3%), reported five or more chronic physical conditions (60.0%), and had not been diagnosed with either depression or anxiety (62.3%).

Partnered LGB older adults were significantly younger than those without partners (Table 1). Partnered respondents were more likely to be female and White, and they were more often in the highest categories of education and income. Single, older adults were more frequently bisexual compared with those partnered who were more likely lesbian or gay. Single respondents more frequently reported having five or more chronic physical illnesses and depression and/or anxiety.

Ordinal regression results (Table 2) indicate that partnership status was significantly associated with general health when controlling for the other variables. Being partnered was associated with better general health in comparison with not being partnered (Table 3). Relationship duration was associated with poorer general health, as was having a household income less than $35,000, reporting five or more physical illnesses, and having depression and/or anxiety. Being White was associated with better general health, as was having 4 or more years of college education relative to having a high school education or less. Age, gender, and sexuality were unrelated to general health when controlling for the other variables.

Table 2.

Ordinal Regression for General Health Among Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Adults, Aged 50-95 Years: Caring and Aging with Pride Project (Range: Excellent to Very Poor)

| Independent variables | b(SE) |

|---|---|

| Partnered/marrieda | −0.35** (0.13) |

| Relationship duration | 0.02*** (0.01) |

| Age | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Female | 0.12 (0.08) |

| White | −0.34** (0.12) |

| Bisexual | 0.08 (0.17) |

| Educationb | |

| 1–3 years college | −0.20 (0.17) |

| ≥4 years college | −0.53** (0.16) |

| Household incomec | |

| $35k–$75k | −0.41*** (0.10) |

| >$75k | −0.82*** (0.12) |

| >5 Physical illnesses | 0.86*** (0.09) |

| Depression and/or anxiety | 0.56*** (0.08) |

| Cut 1 | −1.63 (0.37) |

| Cut 2 | 0.02 (0.37) |

| Cut 3 | 1.36 (0.37) |

| Cut 4 | 2.89 (0.38) |

| Cut 5 | 4.7 (0.42) |

Note. SE = standard error.

N = 2,144. LR = 347.67***

Reference group = Unpartnered (single, divorced, widowed).

Reference group = high school or less.

Reference group = <$35,000.

Table 3.

Predicted Marginal Distribution of Self-Reported General Health for LGB Older Adults of Average Age (50-95 Years) and Average Duration of Current Relationship

| Excellent | Very good | Good | Fair | Poor | Very poor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall samplea | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| For a White lesbian, <4yrs college, med. income, ≥5 illnesses, no depression or anxiety: | ||||||

| Unpartnered | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| Partnered/married | 0.15 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| For a white, lesbian, ≥4 yrs college, high income, <5 illnesses, no depression/anxiety: | ||||||

| Unpartnered | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.02 | <0.01 |

| Partnered | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Non-White, gay male, high school, low income, >5 illnesses, with depression/anxiety: | ||||||

| Unpartnered | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.06 |

| Partnered | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.16 | 0.04 |

Observed proportions.

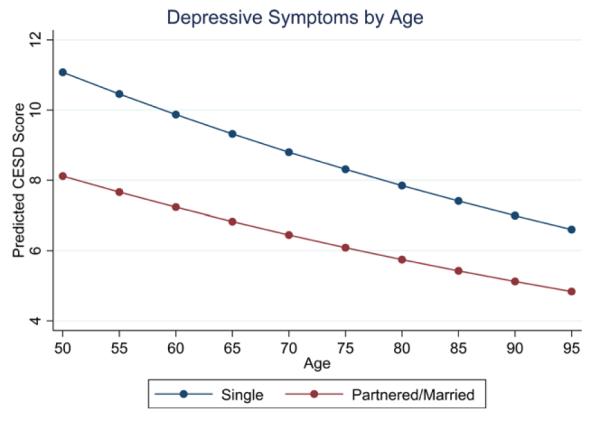

Negative binomial regression results (Table 4)illustrate that being both partnered and older were significantly associated with a lower count of depressive symptoms compared with single LGB older adults, controlling for the other variables (Figure 1). Being partnered decreased the expected count of depressive symptoms by 20.8%, holding the other variables constant. Each additional year of age corresponded with a 1.1% decrease in depressive symptoms, controlling for other covariates. Having an annual household income less than $35,000 and being diagnosed with five or more chronic physical illnesses were also significantly associated with more depressive symptoms. Gender, race, relationship duration, and sexual orientation were not associated with depressive symptoms when controlling for the other variables.

Table 4.

Results of Regressions of Depressive Symptoms (Negative Binomial) for LGB Adults, Aged 50-95 Years: Caring and Aging with Pride Project National Study

| Independent variables | Depressive symptoms b(SE) |

|---|---|

| Partnered/marrieda | −0.31*** (0.06) |

| Relationship duration | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Age | −0.01*** (0.01) |

| Female | 0.01 (0.04) |

| White | −0.07 (0.06) |

| Bisexual | 0.02 (0.09) |

| Educationb | |

| 1–3 years college | 0.02 (0.08) |

| ≥4 years college | −0.12 (0.07) |

| Household incomec | |

| $35k–$75k | −0.28*** (0.05) |

| >$75k | −0.41*** (0.05) |

| >5 Physical illnesses | 0.28*** (0.04) |

| Depression and/or anxiety | – |

| Constant | 2.98*** (0.17) |

Note. SE = standard error.

Reference group = Unpartnered (single, divorced, widowed).

Reference group = high school or less.

Reference group = <$35,000

N = 2088. LR = 249.38***

Figure 1.

Predicted CES-D-S score by age for a White lesbian with <4 years college education, $35,000–$75,000 annual household income, and ≥5 physical illnesses, of average duration of current relationship: Caring and Aging with Pride Project National Study.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with Social Integration Theory, LGB older adults in this sample were significantly more likely to report better general health and fewer depressive symptoms if they were partnered. When controlling for other demographic characteristics, relationship statuses with greater social integration (partnered or married) were associated with better outcomes.

Contrary to findings from some heterosexual samples (Meadows, 2009; DuPre & Meadows, 2007; Lillard & Waite, 1995; Gibb et al., 2011), there is no evidence of a cumulative advantage to being partnered for LGB older adults. When controlling for age, which was not significantly associated with relationship duration, partnership duration was not significantly associated with better outcomes. Although the current relationships reported by respondents ranged from 0 to 65 years in duration, within this sample, depressive symptoms were not significantly associated with longer lasting relationships. In fact, duration was associated with lower self-reported general health.

Although this finding contradicts the cumulative advantage observed among many studies of heterosexual samples, it is consistent with some of the research on heterosexuals that also found relationship duration not significantly associated with better health outcomes for older heterosexuals (Pienta et al., 2000). The lack of a cumulative impact of relationships over time may reflect the diversity of meanings, legal recognition, and social norms associated with same-sex partnerships in contrast to more formally recognized and agreed-upon norms for heterosexuals. Identifying as partnered may reflect more social integration than identifying as single for LGB older adults; however, social stigma and limited public and state recognition likely afford same-sex partners less social integration than their heterosexual counterparts, limiting the cumulative benefits of longer lasting relationships.

Identifying as a member of a same-sex partnership itself may contribute to greater exposure to homophobia and heterosexism in many contexts, the negative consequences of which may nullify the cumulative rewards that might otherwise be observed for longer lasting relationships. The geographic diversity of this sample, including subjects from jurisdictions that explicitly ban legal recognition of same-sex relationships, jurisdictions that simply do not acknowledge them, and jurisdictions that explicitly sanction and provide legal standing to them, may account for a null finding with regard to how relationship duration plays a role in health for LGB older adults.

Limitations

Although the Caring and Aging with Pride Project national survey offers an unprecedented large sample of LGB older adults to study, the nonrandom sampling design limits the ability to generalize findings. LGB older adults who are not connected to service agencies were not sampled. It is not known whether there were systematic differences between those that responded and those that did not respond to the survey. Moreover, the unknown response rate for the portion of respondents who completed the survey online further limits the ability to conclude whether the sample is biased relative to the general population of LGB older adults. The cross-sectional design of the study limits the ability to draw causal inferences between partnership status and health.

Some literature on heterosexual marriage (Pienta et al., 2000; Waldron et al., 2004; Hu & Goldman, 1990) has found a selection effect for the association of health and marriage, whereby healthier adults are more likely to get married and remain longer in marriages than unhealthier adults. Whether the Caring and Aging with Pride Project respondents were healthier before they were partnered or whether being partnered promoted their health consistent with the Social Integration Theory is unknown. Relatively small subsamples of racial and ethnic minority respondents may also make these results underpowered to detect whether important differences between racial and ethnic groups of LGB older adults exist with regard to partnership status and health outcomes.

Implications for Community Practice and Research

An estimated 1.5 million adults in the United States are 65 years of age and older and identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (Gerace, 2012). That number is expected to double by the year 2030. The findings from this study suggest the importance of addressing the relationship between same-sex partnerships and health when considering the growing ranks of older adults among LGB communities. Because partnerships appear to be a health asset for LGB older adults, as they are for heterosexuals, political and policy efforts to publicly sanction same-sex partnerships may have implications for the health of older adults.

The observed relationships between older adult health and depressive symptoms and same-sex partnership status have implications for a wide variety of services provided to older adults. Many LGB older adults report feeling unsafe to identify themselves and their same-sex partners as a couple in their senior living communities (Stein, Beckerman, & Sherman, 2010). Unlike married heterosexuals, LGB residents in nursing homes are frequently denied the right to reside with their partners (LGBT Movement Advancement Project & SAGE, 2010). Institutional policies in senior housing and health care facilities that restrict unmarried older adults from cohabiting may not only separate long-term same-sex partners from sharing social, emotional, and financial resources, but they may also have deleterious effects on their general health and depressive symptoms.

Popular recognition and support for same-sex partnerships is quickly growing in the United States (Saad, 2012), as is the access that same-sex partners have to state-recognized legal statuses (Human Rights Campaign, 2012). Further research is needed to examine how the dynamic policy environment with regard to the legal standing of same-sex partnerships may have long-term consequences on the health of current and future generations of LGB older adults. If opportunities for legal recognition of same-sex partnerships continue to expand and social acceptance grows, further study of contextual factors such as relationship duration and the exercise of legal rights (e.g., second-parent adoptions, surrogate decision making) may observe changing implications of partnership status for LGB older adults.

Additional research should examine further what factors may explain the unexpected negative association in this sample between relationship duration and general health, controlling for age. Longitudinal studies may better isolate causal relationships linking partnership status and health among LGB older adults, as well as document how dramatic shifts in social policy and public opinion affect their well-being during periods of rapid change in social integration, such as we have experienced within the past decade. Additional studies of the mechanisms linking partnership status and health may also help identify important areas in which both community health practices and institutional changes can promote the health of unpartnered older adults.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award No. R01AG026526. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health; Fredriksen-Goldsen, PI.

Contributor Information

Mark Edward Williams, Helen Bader School of Social Welfare, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee..

Karen I. Fredriksen-Goldsen, University of Washington

REFERENCES

- Andersen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale) American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomgren J, Martikainen P, Grundy E, Koskinen S. Marital history 1971–91 and mortality 1991–2004 in England & Wales and Finland. Journal of Epidemiological Community Health. 2012;66:30–36. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.110635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs RH. Marital status and personal well-being: A literature review. Family Relations. 1991;40(1):97–102. [Google Scholar]

- DuPre ME, Meadows SO. Disaggregating the effects of marital trajectories on health. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28(5):623–652. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. In: Suicide: A study in sociology. Spaulding John A., Simpson George., translators. The Free Press; New York: 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Dush CMK, Amato PR. Consequences of relationship status and quality for subjective well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2005;22:607–627. [Google Scholar]

- Frech A, Williams K. Depression and the psychological benefits of entering marriage. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48:149–163. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen FI, Kim H-J, Emlet CA, Muraco A, Erosheva EA, Hoy-Ellis CP, Petry H. The aging and health report: Disparities and resilience among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender older adults. Institute for Multigenerational Health; Seattle, WA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Muraco A. Aging and sexual orientation: A 25-year review of the literature. Research on Aging. 2010;32:372–413. doi: 10.1177/0164027509360355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerace A. SAGE releases guide for improving aging services to older LGBT adults. National Resource Center on LGBT Aging; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.lgbtagingcenter.org/newsevents/newsArticle.cfm?n=32. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb SJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Relationship duration and mental health outcomes: Findings from a 30-year longitudinal study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;198:24–30. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman N, Korenman S, Weinstein R. Marital status and health among the elderly. Social Science and Medicine. 1995;40(11):1717–1730. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00281-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gove WR. The relationship between sex roles, marital status and mental illness. Social Forces. 1972;51:34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR, O’Connell TS. Being lesbian, gay, bisexual and 60 or older in North America. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 2001;13(4):23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson AS, Scott R, Kay DWK. The elderly who live alone. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;20(2):202–209. doi: 10.3109/00048678609161332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Goldman N. Mortality differentials by marital status: An international comparison. Demography. 1990;27(2):233–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Campaign . Human Rights Campaign; 2012. Same-sex relationship recognition laws: State by state. Retrieved from http://www.hrc.org/resources/entry/same-sex-relationship-recognition-laws-state-by-state. [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Boulifard DA, Contrada RJ. Mending broken hearts: Marriage and survival following cardiac surgery. Journal of Health and Behavior. 2012;53(1):33–49. doi: 10.1177/0022146511432342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempen GI. The MOS Short-Form General Health Survey: Single item vs. multiple measures of health related quality of life: some nuances. Psychological Reports. 1992;70(2):608–610. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1992.70.2.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KB, Reis HT. Marriage and long-term survival after coronary artery bypass grafting. Health Psychology. 2012;31(1):55–62. doi: 10.1037/a0025061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobrin FE, Hendershot GE. Do family ties reduce mortality? Evidence from the United States, 1966–1968. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1977;39(4):737–745. [Google Scholar]

- LGBT Movement Advancement Project & SAGE . Improving the lives of LGBT older adults. LGBT Movement Advancement Project & SAGE; New York: 2010. Retrieved from http://www.lgbtagingcenter.org/resources/pdfs/NRCInclusiveServicesGuide2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard LA, Waite LJ. Til death do us part: Marital disruption and mortality. American Journal of Sociology. 1995;100(5):1131–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoli L, Villari P, Pirone G, Boccia A. Marital status and mortality in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science and Medicine. 2007;64:77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows SO. Family structure and fathers’ well-being: Trajectories of mental health and self-rated health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50(2):115–131. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natale AP, Miller-Cribbs JE. Same-sex marriage policy: Advancing social, political, and economic justice. Journal of GLBT Family Issues. 2012;8(2):155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Pienta AM, Hayward MD, Jenkins KR. Health consequences of marriage for the retirement years. Journal of Family Issues. 2000;21:559–586. [Google Scholar]

- Prior PM, Hayes BC. The relationship between marital status and health: An empirical investigation of differences in bed occupancy within health and social care facilities in Britain, 1921–1991. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:124–148. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Riggle EDB, Rostosky SS, Horne SG. Psychological distress, well-being, and legal recognition in same-sex couple relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(1):82–86. doi: 10.1037/a0017942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J, Goldsteen K. The impact of the family on health: The decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1990;52(4):1059–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Saad L. U.S. acceptance of gay/lesbian relations is the new normal. Gallup Politics. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/154634/Acceptance-Gay-Lesbian-Relations-New-Normal.aspx.

- Scafato E, Galluzzo L, Gandin C, Ghirini S, Baldereschi M, Capurso A, Farchi G. Marital and cohabitation status as predictors of mortality: A 10-year follow-up of an Italian elderly cohort. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67:1456–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA, Heyman KM. Health characteristics of adults aged 55 years and over: United States, 2004–2007. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2009. National Health Statistics Reports; No. 16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Hays RD. Marital status, social support, and health transitions in chronic disease patients. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1990;31(4):328–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW. Revisiting the relationships among gender, marital status, and mental health. American Journal of Sociology. 2002;107(4):1065–1996. doi: 10.1086/339225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, Beckerman NL, Sherman PA. Lesbian and gay elders and long-term care: Identifying the unique psychosocial perspectives and challenges. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2010;53(5):421–435. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2010.496478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. Multiple identities and psychological well-being: A reformulation and test of the social isolation hypothesis. American Sociological Review. 1983;48(2):174–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs BD, Ziegelstein RC, Steward DE, Abbey SE, Parakh K, Grace SL. Usefulness of a single-item general self-rated health question to predict mortality 12 months after an acute coronary syndrome. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. 2008;15(4):479–481. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328300b717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tower RB, Stanislav VK, Darefsky AS. Types of marital closeness and mortality risk in older couples. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:644–659. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200207000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ. Does marriage matter? Demography. 1995;32(4):483–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Gallagher M. The case for marriage: Why married people are happier, healthier, and better off financially. Doubleday; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron I, Hughes ME, Brooks TL. Marriage protection and marriage selection: Prospective evidence for reciprocal effects of marital status and health. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;43(1):113–123. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00347-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SK. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User’s Manual. The Health Institute; Boston, MA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wienke C, Hill GJ. Does the ‘marriage benefit’ extend to partners in gay and lesbian relationships?: Evidence from a random sample of sexually active adults. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;30:259–289. [Google Scholar]

- Wight R, LeBlanc AJ, Badgett L. Same-sex legal marriage and psychological well-being: Findings from the California Health Interview Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(2):339–345. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wight RG, LeBlanc AJ, de Vries B, Detels R. Stress and mental health among midlife and older gay-identified men. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(3):503–510. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K. Has the future of marriage arrived? A contemporary examination of gender, marriage and psychological well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(4):470–487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Schimmele CM, Chappell NL. Aging and late-life depression. Journal of Aging and Health. 2012;24(1):3–28. doi: 10.1177/0898264311422599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]