Abstract

Drug shortages in the United States continue to be a significant problem that negatively impacts pediatric patients of all ages. These shortages have been associated with a higher rate of relapse among children with cancer, substitution of less effective agents, and greater risk for short- and long-term toxicity. Effective prevention and management of any drug shortage must include considerations for issues specific to pediatric patients; hence, the Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy Group (PPAG) strongly supports the effective management of shortages by institutions caring for pediatric patients. Recommendations published by groups such as the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition should be incorporated into drug shortage management policies. PPAG also supports the efforts of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to not only address but prevent drug shortages caused by manufacturing and quality problems, delays in production, and discontinuations. Prevention, mitigation, and effective management of drug shortages pose significant challenges that require effective communication; hence, PPAG encourages enhanced and early dialogue between the FDA, pharmaceutical manufacturers, professional organizations, and health care institutions.

INDEX TERMS: drug shortages

BACKGROUND

National drug shortages in the United States disproportionately and negatively impact care of pediatric patients. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and health care institutions should include pediatric considerations in their drug shortage strategies. Hospitals face the frequent challenge of providing safe and effective care to patients during drug shortages. The incidence of drug shortages has increased fourfold over a six year period. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) reported 294 shortages during the first 10 months of 2013.1 The problem is widespread affecting multiple drug classes, including oncology drugs, antibiotics, analgesics, anesthetics, cardiovascular medications, electrolyte solutions, and vitamins.2 Between spring 2010 and fall 2012 availability of every parenteral nutrition product, with the exception of dextrose and sterile water, was affected by a national shortage.3

Effective management of drug shortages presents significant challenges. Health care institutions routinely require rapid access to specific medications to treat patients with acute and emergent conditions.3 Interdisciplinary and interprofessional coordination, communication, and management of drug shortages when necessary are often complicated.3 In 2010, the Institute of Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) reported challenges facing health care practitioners coping with shortages and described significant frustration with a lack of accurate information and advanced warnings, limited access to appropriate alternative medications, and substantial investments of time and resources to manage the drug shortage. Significant negative financial effects have also resulted from management of drug shortages.4

Drug shortages harm patients by adversely impacting drug therapy, causing delays in medical procedures or therapy, and contributing to medication errors.3 Therapeutic alternatives, when available, are frequently associated with increased cost, decreased efficacy, increased side effects, and medication errors resulting from inexperience and lack of knowledge.4,5 In a survey by ISMP, one third of health care providers reported a near miss of patient harm in their facility due to drug shortages.4

DESCRIPTION OF THE ISSUE

Published reports of harm demonstrate the negative impact of drug shortages on pediatric patients. Examples include zinc deficiency dermatitis in extremely premature infants,6 periocular ulcerative dermatitis in newborns following gentamicin ointment administration for ocular prophylaxis during an ophthalmic erythromycin shortage,7,8 an increase in catheter-related bloodstream infections in parenteral nutrition–dependent children attributed to an ethanol shortage,9 a decreased 2-year event-free survival rate in pediatric patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma due to a mechlorethamine shortage,5 and dry scaly skin caused by selenium deficiency in a newborn receiving parenteral nutrition.10 In addition, vaccine shortages may contribute to a decreasing rate of protected infants and children in the community.11

RATIONALE AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Pediatric patients may be at particular risk of harm due to drug shortages because of a comparative increase in the use of impacted medications (e.g., parenteral nutrition) and the decreased amount of quality pediatric data (or FDA-approved indications for pediatric use) to guide the selection of alternative medications. Alternative products may also carry a higher risk of pediatric-specific adverse effects, such as protein binding, infiltration, or excipient-related implications. These factors necessitate the involvement of pediatric pharmacy specialists in discussions of drug shortages, decisions, and strategic planning.

The FDA has established a strategic plan to prevent and mitigate drug shortages.12 However, issues specific to drug shortages impacting pediatric patients are not specifically addressed in this plan. Future revisions of the strategic plan should include a pediatric focus.

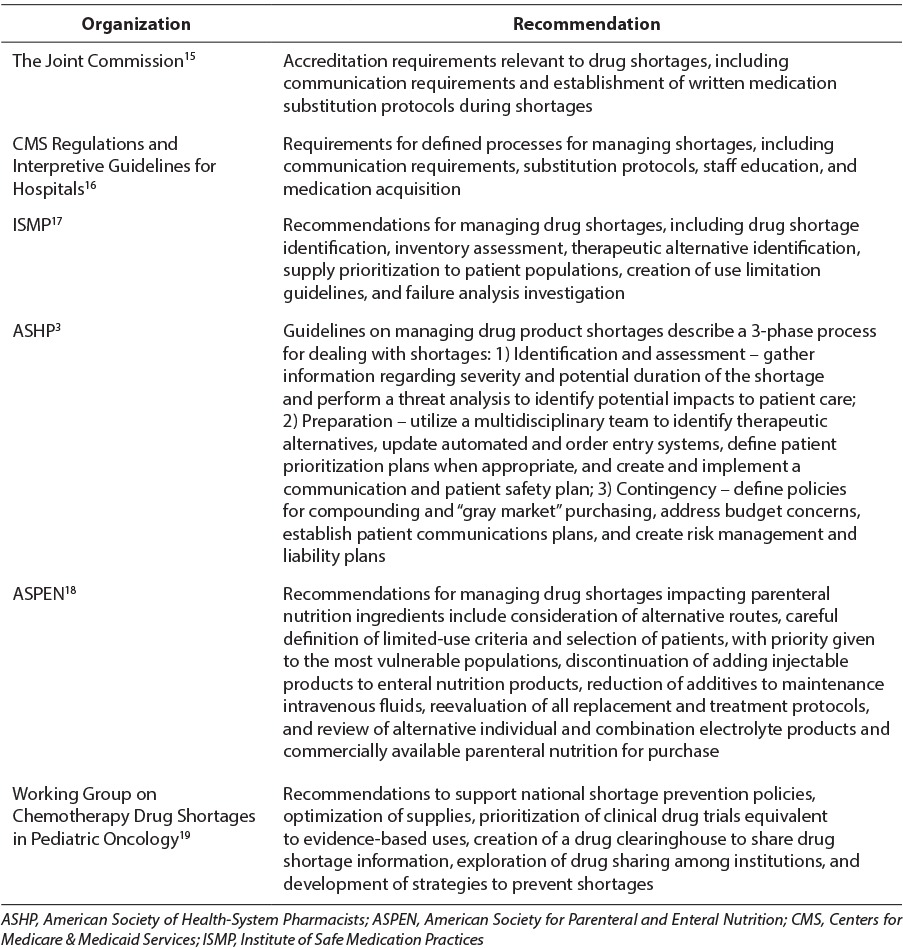

Hospitals must be prepared to deal with drug shortages in a manner that ensures patient safety and effective treatment while minimizing cost and health care resources.3 Strategic planning and pharmacy leadership involvement are crucial to this process.3 The Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy Group (PPAG) supports the recommendations published by key organizations (Table), provided that pediatric specialists are involved at every level in applying these recommendations to clinical and operational practice:

Table.

Published Recommendations from Key Organizations Regarding Drug Shortages

Additionally, information regarding ethical considerations for drug shortage strategies is available in the medical literature. For example, Rosoff and colleagues described an ethical approach to the management of drug shortages that includes transparency in the development and implementation of a drug shortage policy, clinical relevance, opportunities to appeal decisions, complete policy enforcement, and fairness to all patients.13 Gibson and colleagues outlined a 3-stage ethical approach with considerations for maintaining drug supply, appropriate distribution practices and usage restrictions, and fairness in how medication allocation occurs when the supply is insufficient.14

CONCLUSION

An established drug shortage policy or guideline allows hospitals to react in a timely and efficient manner to actual or potential drug shortages, thereby ensuring high-quality clinical care for patients and reduced risks of adverse effects and poor outcomes. An interdisciplinary team that includes representatives from pediatric pharmacy, nursing, medical staff, and other key stakeholders should be involved in the development of a drug shortage policy. The policy should incorporate information based upon national guidelines and recommendations with ethical considerations relevant to the institution.

PPAG recognizes the increasing frequency of drug shortages and potential impact to pediatric patients, including adverse effects and poor treatment outcomes. Institutions caring for pediatric patients should create a drug shortage strategy, guideline, and/or policy with pediatric considerations to facilitate effective management of drug shortages. An FDA strategy for drug shortage prevention and mitigation has the potential to decrease the burden of drug shortages impacting pediatric patients. Future revisions of the FDA strategy should incorporate pediatric-specific considerations.

ABBREVIATIONS

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- ISMP

Institute of Safe Medication Practices

- PPAG

Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy Group

Footnotes

Disclosure The authors and members of the Advocacy Committee declare no conflicts or financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drug Shortages. http://www.ashp.org/menu/DrugShortages. Accessed October 15, 2014.

- 2.Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH. Drug shortages and clinicians. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1499–1500. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox ER, Birt A, James KB et al. ASHP guidelines on managing drug product shortages in hospitals and health systems. Arch Intern Med. 2009;66(15):1399–1406. doi: 10.2146/ajhp090026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ISMP medication safety alert special issue drug shortage: national survey reveals high level of frustration, low level of safety. 2010. http://www.ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/articles/20100923.asp. Accessed October 15, 2014.

- 5.Metzger ML, Billett A, Link MP. The impact of drug shortages on children with cancer - the example of mechlorethamine. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(26):2461–2463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1212468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norton SA, Soghier L, Hatfield J, Lapinski J. Zinc deficiency dermatitis in cholestatic extremely premature infants after a nationwide shortage of injectable zinc. MMWR. 2013;62(7):136–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binenbaum G, Bruno CJ, Forbes BJ et al. Periocular ulcerative dermatitis associated with gentamicin ointment prophylaxis in newborns. J Pediatr. 2010;156(2):320–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nathawad R, Mendez H, Ahmad A et al. Severe ocular reactions after neonatal ocular prophylaxis with gentamicin ophthalmic ointment. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(2):175–176. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181f6c2e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ralls MW, Blackwood A, Arnold M et al. Drug shortage–associated increase in catheter-related blood stream infection in children. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1369–e1373. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanson C, Thoene M, Wagner J et al. Parenteral nutrition additive shortages: the short-term, long-term and potential epigenetic implications in premature and hospitalized infants. Nutrients. 2012;4(12):1977–1988. doi: 10.3390/nu4121977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarthy NL, Irving S, Donahue JG et al. Vaccination coverage levels among children enrolled in the Vaccine Safety Datalink. Vaccine. 2013;31(49):5822–5826. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strategic plan for preventing and mitigating drug shortages food and drug administration. 2013. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugShortages/UCM372566.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2014.

- 13.Rosoff PM, Patel KR, Scates A et al. Coping with critical drug shortages. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1494–1498. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibson JL, Bean S, Chidwick P et al. Ethical framework for resource allocation during a drug supply shortage. Healthc Q. 2012;13(3):26–34. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2013.23040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joint Commission Resources Portal. https://e-dition.jcrinc.com. Accessed October 16, 2014.

- 16.State operations manual appendix A – survey protocol, regulations and interpretive guidelines for hospitals. 2014. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/som107ap_a_hospitals.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2014.

- 17.ISMP medication safety alert weathering the storm: managing the drug shortage crisis. 2010. https://www.ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/articles/20101007.asp. Accessed October 16, 2014.

- 18.Mirtallo JM, Holcombe B, Kochevar M, Guenter P. Parenteral nutrition product shortages: the A.S.P.E.N. strategy. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012;27(3):385–391. doi: 10.1177/0884533612444538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decamp M, Joffe S, Fernandez CV et al. Chemotherapy drug shortages in pediatric oncology: a consensus statement. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):1–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]