Abstract

A major issue for water resource management is the assessment of environmental degradation of lotic ecosystems. The overall aim of this study is to develop a multi-metric fish index for the cyprinid streams of the Caspian Sea Basin (MMICS) in Iran. As species diversity and composition as well as population structure in the studied streams are different to other regions, there is a substantial need to develop a new fish index. We sampled fish and environmental data of 102 sites in medium sized streams. We analysed human pressures at different spatial scales and determined applicable fish metrics showing a response to human pressures. In total, five structural and functional types of metrics (i.e. biodiversity, habitat, reproduction, trophic level and water quality sensitivity) were considered. In addition, we used 29 criteria describing major anthropogenic human pressures at sampling sites and generated a regional pressure index (RPI) that accounted for potential effects of multiple human pressures.

For the MMICS development, we first defined reference sites (least disturbed) and secondly quantified differences of fish metrics between reference and impaired sites. We used a Generalised Linear Model (GLM) to describe metric responses to natural environmental differences in least disturbed conditions. By including impaired sites, the residual distributions of these models described the response range of each metric to human pressures, independently of natural environmental influence.

Finally, seven fish metrics showed the best ability to discriminate between impaired and reference sites. The multi-metric fish index performed well in discriminating human pressure classes, giving a significant negative linear response to a gradient of the RPI. These methods can be used for further development of a standardised monitoring tool to assess the ecological status and trends in biological condition for streams of the whole country, considering its complex and diverse geology and climate.

Keywords: Multi-metric fish index, Regional pressure index, Cyprinid rivers, Iran

Introduction

The maintenance and restoration of aquatic ecosystems have become a common goal for sustainable river basin management. The ultimate effect of human activities in river catchments leads to pressures on the biota and biological processes (Karr and Chu, 1999). Fish among other organisms (i.e. phytoplankton, macrophytes, macro-invertebrates) have been regarded as a particularly effective biological indicator of aquatic environmental quality and anthropogenic stress, based on their sensitivity and advantages regarding e.g. taxonomy, trophic levels, economic and aesthetic values (Karr and Chu, 1999; Schmutz et al., 2000, 2007; Hering et al., 2010).

The first fish-based assessment as IBI (Index of Biotic Integrity) was developed by Karr (1981). Then, several environmental assessment methods, which were mostly inspired by this seminal work, were developed in different regions, especially in America and Europe over the last decades (e.g. Hugueny et al., 1996; Angermeier et al., 2000; Pont et al., 2006; Schmutz et al., 2007; Meador et al., 2008). To our knowledge, among 48 countries in Asia with an extent of 4.43 million km2, multi-metric fish indices were only developed in a few countries like India (Ganasan and Hughes, 1998), Pakistan (Qadir and Malik, 2009) and China (Liu et al., 2010; Jia and Chen, 2013).

Iran's area is 1,629,807 km2. It is located in the Palearctic zoogeographical realm bordering the Oriental and African ones (Coad and Vilenkin, 2004) and thus, wide ranges of geographical and geological conditions coupled with climatologically diverse environments provide specific and enormous species diversity in Iran. In this context, a new index, based on the specific biotic and environmental conditions of Asian/Iranian rivers, is required to reflect regional differences in fish distribution and assemblage structure.

Furthermore, water-quality monitoring programmes in Iran have been mainly based on the determination of physical and chemical parameters; in contrast, the biological assessment of rivers especially by fish is very limited, but should be implemented in future for several reasons. In Iran, so far, ecological monitoring by fish is typically based on species presence/absence data, however it is not used to evaluate ecological conditions and to inform decision makers.

Nevertheless, a first fish-based multi-metric assessment index for cold-water streams for the Caspian Sea Basin in Iran was developed recently by Mostafavi et al. (submitted for publication). However, the fish species diversity of these cold-water streams was very low (i.e. reference rivers are mostly occupied by brown trout, Salmo trutta only), which resulted in only two fish metrics (related to density and population structure of brown trout) that were proposed for this index. For multi-species rivers, an IBI is understood to be a multi-metric index that integrates structure, composition, trophic ecology, and reproductive attributes of fish assemblages at multiple levels of ecological organisation (Karr and Chu, 1999). As these objectives were not principally examined for Iran to date, the recent study aims to develop a multi-metric index for cyprinid streams (i.e. streams dominated by cyprinid species) in the Iranian Caspian Sea Basin adjusted to the regional fish fauna. This is especially important, as northern and western Iran is considered as part of the Irano-Anatolian biodiversity hot spot, which contains many centres of local endemism – and consequently, its species diversity and composition as well as the population structure can be different to other regions in Europe and Asia (Majnonian et al., 2005; Abdoli and Naderi, 2009; Coad, 2014). For example, this basin supports species such as Barbus lacerta, Barbus mursa, and Capoeta capoeta which have not been analysed in IBI studies so far.

IBIs are based on the assumption that various human pressures, e.g. hydrological and morphological alterations, connectivity disruptions, water quality problems and biological pressures (e.g. due to invasive species) as well as various land uses affect riverine fish assemblages (e.g. Kiabi et al., 1999; Abdoli, 2000; Mostafavi, 2007; Abdoli and Naderi, 2009; Mostafavi et al., 2014). These pressures have not been quantified for the cyprinid streams of the Caspian Sea Basin so far. Moreover, these pressures led some species of this basin to be categorised in the Red List of IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature, http://www.iucnredlist.org/) (e.g. Stenodus leucichthys: extinct in the wild; Acipenser persicus, Acipenser stellatus, Acipenser nudiventris, Acipenser gueldenstaedtii, Huso huso: critically endangered; Caspiomyzon wagneri: near threatened; Luciobarbus brachycephalus, Acipenser ruthenus: vulnerable). To our knowledge, all existing related studies in Iran (e.g. Qaneh et al., 2006; Kamali and Esmaeili, 2009; Sharifinia et al., 2012) exclusively described human pressures (except water quality) at local scale and did not quantify all types of pressures in different spatial scales. However, it is of great importance to quantify different types of pressures at various spatial scales, in order to better understand the response of biota to human activities (Schinegger et al., 2012, 2013; Trautwein et al., 2012). Furthermore, in this study we examine appropriate fish metrics for showing a response to specific human pressure types for cyprinid rivers since this theory was not even tested for the first IBI attempt in Iran by Mostafavi et al. (submitted for publication).

IBIs are among the most appropriate methods to evaluate running waters based on predictive models (e.g. Pont et al., 2006, 2009). These models incorporate numerous possible sources of inter- and/or intra-regional variations in assemblage and population structure caused by variations in natural environmental factors (e.g. Oberdorff et al., 2001, 2002; Pont et al., 2006, 2009). These models enable site-specific estimation of metric values expected when the human pressures are absent in accordance with environmental characteristics of the measured site, while alternative procedures require development of a classification system (Oberdorff et al., 2001). As species diversity and composition as well as the population structure of reference sites of the cyprinid rivers of the Caspian Sea Basin are completely different to other regions of the world, these methods have to be tested for the environmental conditions of this region. We selected the Caspian Sea Basin because this basin represents a homogenous bio-geographical and ecological unit and availability of environmental and fish assemblage data is better here than in other regions in Iran.

Therefore, the objective of this paper is to develop a model-based fish index to assess the ecological status of cyprinid streams of the Caspian Sea Basin in Iran. This method will integrate the following steps: (1) quantifying human pressures at different spatial scales, (2) identifying applicable fish metrics showing a response to human pressures and (3) integrating these metrics into a multi-metric fish index.

Materials and methods

Our methods are generally based on the methods developed by EFI+Consortium (2009) and relevant publications deriving from this project (e.g. Pont et al., 2006; Logez and Pont, 2011; Schinegger et al., 2012, 2013). However, major methodological differences exist regarding the amount and type of human pressures included and the amount and type of fish metrics tested. Moreover, we included different types of environmental descriptors as well as some different statistical distributions and link functions for the modelling of fish metrics. Finally, some dissimilar criteria for the selection of the core fish metrics for the development of the fish index and some different tests for further analysis were applied.

Study area

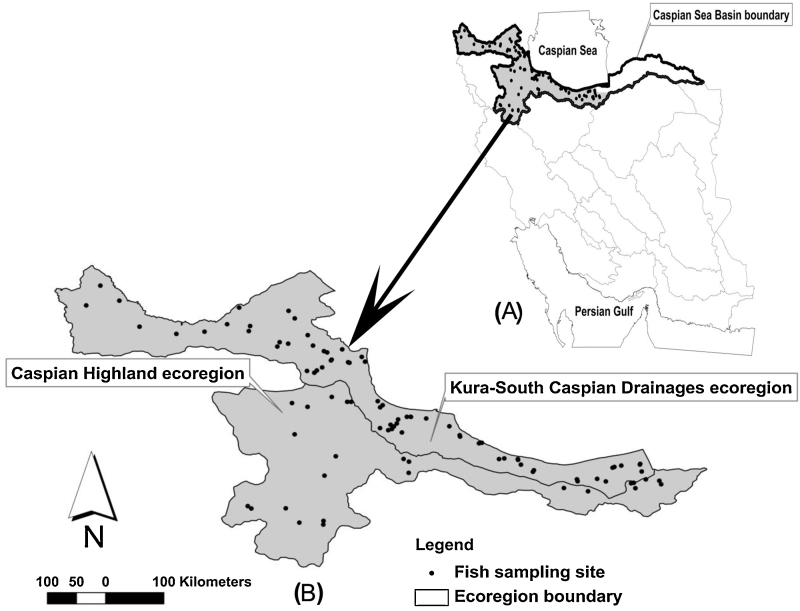

The Caspian Sea Basin with an area of 182,100 km2 encompasses three ecoregions on Iranian territory (Kura-South Caspian Drainages, Caspian Highlands and Turan Plain) (Abell et al., 2008). This basin is inhabited by 116 fish taxa in total (101 native plus 15 alien) (Esmaeili et al., 2014). We selected cyprinid streams of two ecoregions (Kura-South Caspian Drainages, Caspian Highlands) (Fig. 1 A and B) for this study.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of fish sampling sites in cyprinid streams of two freshwater ecoregions of the Caspian Sea Basin (A, B).

Fish data sampling and definition of sampling sites

First according to the land use/cover map and dam distribution layer, subcatchments delineated from the CCM2 map (River and Catchments Database for Europe, version 2.1 provided by Vogt et al. (2003, 2007) and de Jager and Vogt (2010)) were pre-classified as reference (class 1 according to Table 1) or impaired subcatchments (class >1 according to Table 1) using ArcGIS Desktop 9.3 (ESRI© 1999–2008). Afterwards, 75 sites of small to medium-sized rivers (width ≤ 20 m) were randomly selected in the reference subcatchments and 75 in the impaired subcatchments. Other pressure variables i.e. morphology, hydrology, water quality and biology were measured according to Table 1 in the field during the sampling and used together with the pre-classification for the final classification of sites, i.e. reference sites class 1 and impaired sites class >1 according to Table 1.

Table 1.

Human pressure classification into six human pressure types (LUP: land use pressure, CP: connectivity pressure, MP: morphological pressure, HP: hydrological pressure, WQP: water quality pressure, BP: biological pressure) and their definitions.

| Human pressure variable | Type | Code | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | LUP | LU_agri_sit | Range: 50 m from stream; 1 = none, 3 = along one side, 5 = along both sides |

| Urbanisation | LUP | LU_urb_sit | Range: 100 m from stream; 1 = <5%, 3 = ≥5% and <10%, 5 = ≥10% |

| aAgriculture | LUP | LU_agri_pc | Extent and pressure of agriculture and silviculture; 1 = <10%, 3 = ≥10% and <40%, 5 = ≥40% |

| aUrbanisation | LUP | LU_urb_pc | Extent and pressure of urban areas; 1 = <1%, 3 = ≥1% and <15%, 5 = ≥15% |

| aAgriculture | LUP | LU_agri_dr | Extent and pressure of agriculture and silviculture; 1 = <10%, 3 = ≥10% and <40%, 5 = ≥40% |

| aUrbanisation | LUP | LU_urb_dr | Extent and pressure of urban areas; 1 = <1%, 3 = ≥1% and <15%, 5 = ≥15% |

| Migration barrier upstream | CP | C_B_s_up | Barriers on the segment level upstream; 1 = no, 3 = partial, 3 = yes |

| Migration barrier downstream | CP | C_B_s_do | Barriers on the segment level downstream; 1 = no, 4 = partial, 4 = yes |

| Channelisation | MP | M_channel | Alteration of natural morphological channel plan form; 1 = no, 3 = intermediate, 5 = straightened |

| Channelisation | MP | M_crosssec | Alteration of cross-section; 1 = no, 3 = intermediate, 5 = technical cross-section/U-profile |

| Channelisation | MP | M_instrhab | Alteration of in-stream habitat condition; 1 = no, 3 = intermediate, 5 = high |

| aChannelisation | MP | M_embankm | Artificial embankment; 1 = no (natural status), 2 = slight (local presence of artificial material for embankment), 3 = intermediate (continuous embankment but permeable), 5 = high (continuous, no permeability) |

| Channelisation | MP | M_ripveg | Alteration of riparian vegetation close to shoreline; 1 = no, 2 = slight, 3 = intermediate, 5 = high (no vegetation) |

| Flood protection | MP | M_floodpr | Presence of dykes for flood protection; 1 = no, 3 = yes |

| aFlood protection | MP | M_remfloodpl | If the river has a former floodplain, proportion of connected floodplain still remaining. Floodplain = area connected during the flood; 1 = >50%, 2 = 10–50%, 3 = <10%, 5 = some water bodies remaining or no |

| Sedimentation | MP | M_sediment | Input of fine sediment (mainly mineral input; bank erosion, erosion from agricultural land); 1 = no, 3 = yes |

| aFlow velocity increase | HP | H_veloincr | Pressure on flow conditions (mean velocity) due to channelisation, flood protection, etc.; 1 = no, 3 = yes |

| Impoundment | HP | H_imp | Natural flow velocity reduction on site because of impoundment; 1 = no (no impoundment), 3 = intermediate, 5 = strong |

| Hydropeaking | HP | H_hydrop | Site affected by hydropeaking; 1 = no (no hydropeaking), 3 = partial, 3 = yes |

| Water abstraction | HP | H_waterabstr | Site affected by water flow alteration/minimum flow; 1 = no (no water abstraction), 3 = intermediate (less than half of the mean annual flow), 5 = strong (more than half of mean annual flow) |

| aReservoir flushing | HP | H_reflush | Fish fauna affected by flushing of reservoir upstream of site; 1 = no, 3 = yes |

| bTemperature pressure | HP | H_tempimp | Water temperature pressure; 1 = no, 3 = yes |

| bEutrophication | WQP | W_eutroph | Artificial eutrophication; 1 = no, 3 = low, 4 = intermediate (occurrence of green algae), 5 = extreme (oxygen depletion) |

| bAcidification | WQP | W_aci | Acidification; 1 = no, 3 = yes |

| bOrganic siltation | WQP | W_osilt | Siltation; 1 = no, 3 = yes |

| a,b Organic pollution | WQP | W_opoll | Is organic pollution observed; 1 = no, 3 = intermediate, 5 = strong |

| bToxicity | WQP | W_toxic | Toxic priority substances (organic and nutrient appearance); 1 = no or very minor, 3 = weak (important risk, link to particular substance), 5 = high concentration (a clearly known input) |

| Pressure of exploitation | BP | B_explo | Fishing, at site affecting fauna, information based on local fishermen; 1 = no, 3 = intermediate, 5 = strong |

| Introduction of fish | BP | B_intro | New fish species to river basin; 1 = no introduction, 2 = introduction, but no reproduction and low density, 3 = not reproduction, high density, 4 = reproducing, low density, 5 = reproducing, high density |

Excluded variables after correlation test.

According to Iranian water quality standard (Sazman Hefazat Mohit Zist Iran, 2014).

However, it is important to state that finding a site without continuity interruptions (e.g. ground sills) is almost impossible in this basin, based on our personal experience and other literature (e.g. Kiabi et al., 1999; Mostafavi et al., 2004; Abdoli and Naderi, 2009). Therefore, according to Hughes et al. (1986) and Stoddard et al. (2006), when real reference sites are missing, least disturbed conditions are selected instead.

During field work, 48 sites were rejected due to one of the following reasons: not accessible, dry, river size and depth not suitable for sampling, turbidity of water or flow velocity too high. Finally, 50 sites remained as reference and 52 as impaired sites.

Fish sampling was undertaken in autumn (2012) due to low flow conditions and presence of different size classes of fish according to the CEN standard (CEN, 2003). The length of sampling sites was calculated as 10–20 times the stream width and at least a distance of 100 m was sampled (Langdon, 2001; EFI+Consortium, 2009). In addition, all sampled sites had more than 50 caught individuals to minimise the risk of false absences.

We established one stop net in the upstream reach and sampled one pass the whole river width with one anode for each 5 m wetted width followed by two or three hand-netters. The sampling team moved slowly upstream to cover all typical habitats with a sweeping movement of the anodes, while attempting to draw fish out of hiding with the electrofisher (EFI+Consortium, 2009). The stunned fish were collected by two additional persons who accompanied the electric fishing team. After species identification according to Abdoli (2000), Abdoli and Naderi (2009) and Esmaeili et al. (2010, 2014) abundance and weight of each species were measured. All fish were released back into the stream afterwards.

Environmental data sampling

For each sampling site, eleven environmental parameters were measured once during the sampling (Table 2): average bankfull width (maximum width the stream attains, typically marked by a change in vegetation, topography, or texture of sediment), average wetted width, flow velocity, water temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, electrical conductivity (EC), turbidity, NO3−, NO2− and PO43−.

Table 2.

Environmental variables measured at the sampling sites.

| Average bankfull width (m) | Average wetted width (m) | Flow velocity (m/s) | Water temperature (°C) | DO (mg/l) | pH | EC (μS/cm) | Turbidity (NTU) | NO3− (mg/l) | NO2− (mg/l) | PO43− (mg/l) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All sites (N = 102) | Median | 15.1 | 7.4 | 0.7 | 17.0 | 8 | 8 | 537 | 19 | 1.44 | 0.06 | 1.68 |

| SD | 11.6 | 4.6 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 1 | 0 | 357 | 192 | 1.30 | 0.03 | 1.10 | |

| Min | 4.2 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 13.0 | 3 | 7 | 151 | 2 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Max | 52 | 20.0 | 1.8 | 24.0 | 14 | 9 | 1780 | 1185 | 9.60 | 0.17 | 5.70 | |

| Reference sites (N = 50) | Median | 15.2 | 7.7 | 1.0 | 16.0 | 9 | 8 | 319 | 7 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.38 |

| SD | 9.0 | 3.5 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 1 | 0 | 122 | 7 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.23 | |

| Min | 5.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 13.0 | 8 | 7 | 151 | 2 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Max | 47.6 | 17.5 | 1.8 | 21.0 | 11 | 9 | 415 | 25 | 0.53 | 0.01 | 0.79 | |

| Impaired sites (N = 52) | Median | 15.0 | 7.0 | 0.5 | 18.0 | 8 | 8 | 756 | 30 | 2.85 | 0.12 | 2.98 |

| SD | 14.2 | 5.8 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 2 | 0 | 592 | 376 | 2.58 | 0.06 | 1.97 | |

| Min | 4.2 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 13.0 | 3 | 7 | 166 | 4 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.11 | |

| Max | 52.0 | 20.0 | 1.8 | 24.0 | 14 | 9 | 1780 | 1185 | 9.60 | 0.17 | 5.70 |

Abbreviation: N: number of sites, SD: mean standard deviation, min: minimum, max: maximum.

In order to calculate the flow velocity, first the time that an object (e.g. small sticks) needs to pass through a defined segment was measured three times, and then the mean time value divided by the segment length was used as an estimate for flow velocity. In addition, water temperature, pH and EC were measured by Multi-parameter Water Analyser Portable (HANNA HI 9828); DO by Oxygen Meter Portable (HACH HQ30D); turbidity by Turbiditimeter Portable (HACH 2100Qis); NO3−, NO2− and PO43− by Multi-parameter Analyser Portable (HACH DR/890).

Human pressures data collection

Various human pressures were collected for each sampling site according to Degerman et al. (2007), EFI+Consortium (2009) and Schinegger et al. (2012) (Table 1).

The dataset incorporated 29 pressure variables associated with the following six pressure types: (1) land use, (2) connectivity, (3) morphology, (4) hydrology, (5) water quality and (6) biology (Table 1). Human pressures were assessed at up to four spatial scales: drainage, primary catchment, segment and site. “Drainage” is the contributing area upstream of the site, “primary catchment” is the smallest level of catchment classification in the CCM2 database (Vogt et al., 2003, 2007; de Jager and Vogt, 2010), “segment” is considered as a 1 km long stretch for small rivers (catchment <100 km2) and 5 km for medium-sized rivers (catchment ≤500 km2). Finally, the site level is the area sampled by electric fishing.

Land use pressures were measured on drainage, primary catchment and site levels. Information on connectivity pressure was collected on segment and catchment level but in our study both scales had the same amount of this pressure, therefore, only the segment level is indicated in Table 1. Finally, the remaining pressures refer to the site level (Table 1).

All pressure variables were classified along a five-step graded classification scheme as follows: (1) high, (2) good, (3) moderate, (4) poor and (5) bad status. In fact, in cases of limited pressure information a reduced number of classes were used, whereby pressures with low evidence were classified as class 3 and pressures with high evidence as class 4 or 5. We applied Spearman's rank correlation test to identify redundant variables in order to exclude variables with high co-linearity (ρ > |0.70|).

Data management and software

Data regarding climatic and topographical variables (e.g. annual mean air temperature, precipitation, slope, drainage size) as well as land use and connectivity information were extracted from related layers in the software ArcGIS Desktop 9.3 (ESRI© 1999–2008). All table-structured data from GIS as well as parameters recorded in the field were managed in MS Excel© (Microsoft, 2010). Further analyses on pressure types, regional pressure index (RPI) calculation and modelling were processed in IBM SPSS Statistics 21.

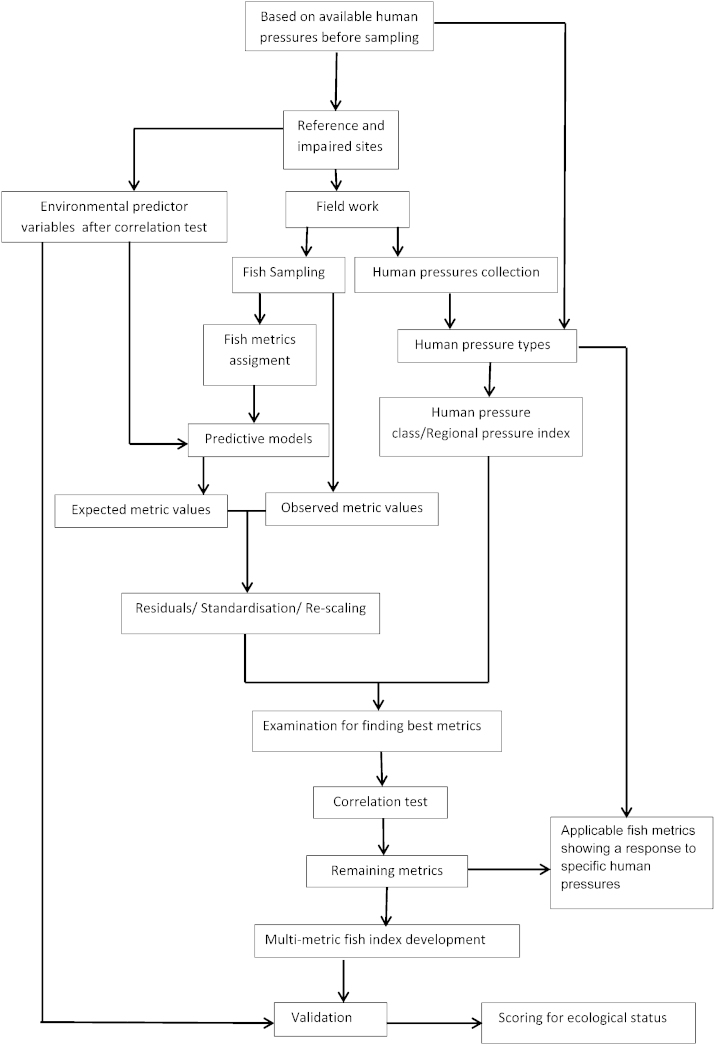

Fig. 2 shows the workflow of the modelling process and multi-metric fish index development at a glance. The assessment and index method development comprises in general five steps as follows.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart describing the procedure of multi-metric fish index (MMICS) development.

Method development step 1: calculation of the regional pressure index (RPI)

To evaluate the pressure status of cyprinid rivers in terms of different human pressures, first, after excluding correlated variables, the instream morphology pressure index (M_morph_instr) was computed according to Schinegger et al. (2012):

| (1) |

Subsequently, a single index for each of the six dominating pressure types, i.e. land use (LUP), connectivity (CP), morphology (MP), hydrology (HP), water quality (WQP), and biology (BP) was calculated by averaging the single pressure parameter values of classes 3, 4 and 5 – to avoid values <3 compensating for values ≥3 (Schinegger et al., 2012).

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

Afterwards, we calculated the number of pressure types affected (“affected types”). In our study, this value varied from one to five depending on how many of the six pressure type indices (LUP, CP, MP, HP, WQP and BP) were ≥3 (according to Schinegger et al., 2012).

Finally, to indicate the degradation of a site by multiple pressures into one single index value, we further calculated a regional pressure index (RPI) for each site as follows:

| (8) |

The RPI varied from 0 to 25, because the maximum pressure types occurred for a site was 5 out of 6. Finally, RPI was rescaled into five classes according to the number of pressure types involved, hereafter it was named human pressure class: class 0 – containing values less than 3 (unimpaired/slightly impaired sites (reference sites are also included in this class)); class 1 – values ranging from 3 to 5 (single pressure from respectively one type); class 2 – values ranging from 6 to 8 (double pressures from respectively two types); class 3 – values ranging from 9 to 11 (triple pressures from respectively three types); class 4 – values greater than 11 (multiple pressures from respectively four and five types).

Method development step 2: selection and evaluation of environmental predictor variables

In this step, a limited number of candidate predictor variables that are major descriptors of river habitat at the reach and regional scale were actually selected for site-specific predictions of reference metric values according to e.g. Oberdorff et al. (2001, 2002), Buisson et al. (2008), Pont et al. (2009), Logez et al. (2012) and Filipe et al. (2013). It was assumed that they are relatively unaffected by human pressures. For instance, drainage size is used for potential habitat capacity as a substitute for river size (as a direct measure of local stream size may be affected by flow and channel alteration). For stream fish, temperature also appears to be one of the main determinant factors of spatial distribution. Air temperatures (i.e. annual mean air temperature (Tmean), July mean air temperature (Tmax), January mean air temperature (Tmin) plus the thermal range between January and July (Trange)) are highly correlated with water temperatures but less affected by local human pressures. Annual mean precipitation characterises the local runoff, and average slope is a surrogate for substrate size and water velocity. All these predictors are fully characterised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Predictor variable characteristics of sampling sites.

| Elevation (m) | Drainage size (km2) | Slope (%) | Precipitation (mm) | Tmean (°C) | Tmax (°C) | Tmin (°C) | Trange (°C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All sites (N = 102) | Median | 683 | 143 | 16 | 673 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 10 |

| SD | 552 | 152 | 5 | 317 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | |

| Min | 18 | 9 | 3 | 291 | 7 | 8 | 0 | 1 | |

| Max | 1675 | 500 | 25 | 1407 | 17 | 21 | 12 | 13 | |

| Reference sites (N = 50) | Median | 628 | 114 | 17 | 630 | 14 | 19 | 8 | 11 |

| SD | 635 | 128 | 4 | 238 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| Min | 18 | 9 | 3 | 291 | 7 | 8 | 0 | 1 | |

| Max | 1641 | 491 | 25 | 1124 | 16 | 21 | 11 | 13 | |

| Impaired sites (N = 52) | Median | 731 | 266 | 12 | 752 | 16 | 21 | 11 | 10 |

| SD | 622 | 159 | 6 | 361 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| Min | 28 | 15 | 5 | 318 | 9 | 15 | 3 | 8 | |

| Max | 1675 | 500 | 23 | 1407 | 17 | 21 | 12 | 12 |

Abbreviations: Tmean: annual mean air temperature, Tmax: July mean air temperature, Tmin: January mean air temperature, Trange: the thermal amplitude between January and July, N: number of sites, SD: mean standard deviation, min: minimum, max: maximum.

Forest and grassland regions (according to land use/cover map) were also included in the modelling process because these regions can significantly influence the density and biomass of some species (e.g. brown trout, Mostafavi et al., submitted for publication). The two freshwater ecoregions plus forest and grassland regions were coded and entered in the models as nominal (categorical) variables.

The climatic variables (air temperature and precipitation) were obtained from the WorldClim predictors, which are often used to characterise current climatologic conditions and seasonality. The WorldClim data describe 50 years of monthly means collected at climate stations between 1950 and 2000 (Hijmans et al., 2005, 2007) and are interpolated at 30 arc-seconds grid extent (approximately 1 km at the equator). Other topographical variables (i.e. slope, drainage size) were extracted from CCM2, which is based on a 100 m resolution digital elevation model (Vogt et al., 2003, 2007; de Jager and Vogt, 2010).

All predictor variables (except freshwater ecoregions plus forest and grassland regions) were examined for co-linearity by Spearman's rank correlation (ρ), if two variables were highly correlated (ρ > |0.70|) one of them was excluded.

Method development step 3: fish metric description, selection, modelling, standardisation and rescaling

In this step, models were used to predict values for each fish metric and for a given site in the absence of human pressures (i.e. a value corresponding to “a reference condition”). These predicted metric values were computed from environmental predictor variables using Generalised Linear Models. The methodology used for metric selection and modelling was mostly derived from Oberdorff et al. (2002), Pont et al. (2006, 2009), EFI+Consortium (2009), Logez and Pont (2011), Moya et al. (2011), Marzin et al. (2012) and Schinegger et al. (2013) as follows.

Fish metrics description

Similar to other studies (e.g. Hughes et al., 2004; EFI+Consortium, 2009; Schinegger et al., 2013), each collected species was assigned to five structural and functional types of metrics: biodiversity, habitat, reproduction, trophic level and water quality sensitivity. These attributes were extracted from literature (e.g. Abdoli, 2000; Abdoli and Naderi, 2009; EFI+Consortium, 2009; Esmaeili et al., 2010; Coad, 2014) and fish experts in Iran (Table 4). In fact, 12 fish metric types of different variants (absolute and relative number of species, density (n/ha) and biomass (kg/ha)) were pre-selected for further analyses (Table 5). These variants reflect most of the important ecological aspects of fish assemblages according to Noble et al. (2007) and Schinegger et al. (2013). Fish metrics like tolerant and alien ones were “0” in the reference sites (i.e. not present) or were highly variable or unresponsive to human pressures (like intermediate metrics). Therefore, these metrics were initially excluded according to Hughes et al. (1998) and Angermeier and Davideanu (2004). Finally, 69 fish metrics were used as candidate metrics for the modelling procedure (see Table 5).

Table 4.

Names and guilds of 22 fish species sampled in Cyprinid streams.

| Species_name | Family | WQgen | WQO2 | HTOL | Hab | Atroph | Repro | HabSp | Native/alien | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acanthalburnus microlepis | Cyprinidae | IM | O2IM | HIM | EURY | INSV | LITH | EUPAR | Na |

| 2 | Alburnus chalcoides | Cyprinidae | TOL | O2IM | HINTOL | EURY | OMNI | LITH | LIPAR | Na |

| 3 | Alburnoides eichwaldii | Cyprinidae | INTOL | O2INTOL | HINTOL | RH | INSV | LITH | RHPAR | Na |

| 4 | Alburnus filippii | Cyprinidae | INTOL | O2INTOL | HINTOL | RH | INSV | LITH | EUPAR | Na |

| 5 | Alburnus hohenackeri | Cyprinidae | TOL | O2IM | HTOL | EURY | PLAN | PHLI | EUPAR | Na |

| 6 | Barbus lacerta | Cyprinidae | INTOL | O2INTOL | HINTOL | RH | INSV | LITH | RHPAR | Na |

| 7 | Capoeta capoeta | Cyprinidae | IM | O2IM | HIM | RH | HERB | LITH | RHPAR | Na |

| 8 | Carassius carassius | Cyprinidae | TOL | O2TOL | HTOL | LIMNO | OMNI | PHYT | LIPAR | Na |

| 9 | Hemiculter leucisculus | Cyprinidae | TOL | O2TOL | HTOL | EURY | OMNI | PELA | EUPAR | Al |

| 10 | Luciobarbus capito | Cyprinidae | INTOL | O2INTOL | HINTOL | RH | INSV | LITH | RHPAR | Na |

| 11 | Luciobarbus mursa | Cyprinidae | INTOL | O2INTOL | HINTOL | RH | INSV | LITH | RHPAR | Na |

| 12 | Pseudorasbora parva | Cyprinidae | TOL | O2TOL | HTOL | EURY | OMNI | PHLI | EUPAR | Al |

| 13 | Rhodeus amarus | Cyprinidae | INTOL | O2IM | HINTOL | LIMNO | OMNI | OSTRA | LIPAR | Na |

| 14 | Squalius cephalus | Cyprinidae | TOL | O2IM | HTOL | RH | OMNI | LITH | RHPAR | Na |

| 15 | Cobitis sp. | Cobitidae | IM | O2IM | HIM | RH | INSV | PHYT | EUPAR | Na |

| 16 | Sabanejewia aurata | Cobitidae | IM | O2IM | HIM | RH | INSV | PHYT | EUPAR | Na |

| 17 | Neogobius pallasi | Gobiidae | TOL | O2IM | HTOL | EURY | INSV | SPEL | EUPAR | Na |

| 18 | Neogobius melanostomus | Gobiidae | TOL | O2IM | HTOL | EURY | INSV | LITH | EUPAR | Na |

| 19 | Paracobitis malapterura | Nemacheilidae | INTOL | O2IM | HIM | RH | INSV | LITH | EUPAR | Na |

| 20 | Oxynoemacheilus sp. | Nemacheilidae | IM | O2IM | HIM | RH | INSV | LITH | EUPAR | Na |

| 21 | Gambusia holbrooki | Poeciliidae | TOL | O2TOL | HTOL | LIMNO | INSV | VIVI | LIPAR | Al |

| 22 | Salmo trutta | Salmonidae | INTOL | O2INTOL | HINTOL | RH | INSV | LITH | RHPAR | Na |

Abbreviations: WQgen: water quality tolerance general, IM: intermediate, TOL: tolerant, INTOL: intolerant; WQO2: water quality tolerance O2, O2IM: intermediate, O2INTOL: intolerant, O2 tolerant: tolerant; HTOL: Habitat degradation tolerance, HIM: intermediate, HINTOL: intolerant, HTOL: tolerant; HAB: habitat, EURY: eurytopic, RH: rheophilic, LIMNO: limnophilic; Atroph: Adult trophic guild, INSV: insectivorous, OMNI: omnivorous, PLAN: planktivorous, HERB: herbivorous; Mig: Migration guild, RESID: resident, POTAD: potamodrom; Repro: reproductive guild, LITH: lithophilic, PHLI: phyto-lithophilic, PHYT: phytophilic, PELA: pelagophilic, OSTRA: ostracophilic, VIVI: viviparous, SPEL: speleophilic; HabSp: habitat spawning preferences, EUPAR: euryoparous, LIPAR: limnoparous, RHPAR: rheoparous; Na: native, Al: alien.

Table 5.

Name and definition of candidate metrics as well as metrics fitted well in the modelling process (modelled metrics), metrics excluded in reaction to human pressures (excluded metrics), core metrics selected for multi-metrics fish index after correlation test (core metrics).

| Trait | Definition | Type | Modelled metrics | Excluded metrics | Core metrics | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nsp-all | Total number of fish species, including native and alien species. | biodiv | dens, biom | dens | ||

| Nsp-native | Number of native species. | biodiv | nsp, dens, biom | nsp | decr | |

| Nsp-alien | Number of alien species. | biodiv | ||||

| Wqgen-INTOL | In general intolerant to usual (national) water quality parameters. | wq | all except perc-dens | nsp | biom | decr |

| WQO2-O2INTOL | Intolerant to low oxygen concentration (O2), requiring >6 mg/l dissolved oxygen concentration. | wq | biom, perc-biom, dens | perc-biom, perc-nsp | dens | decr |

| HTOL-HINTOL | Habitat degradation intolerance. | hab | all except perc-dens | nsp, perc-biom | biom | decr |

| Hab-RH | Degree of rheophily (habitat). Fish prefer to live in a habitat with high flow conditions and clear water. | hab | all except perc-dens | nsp, perc-nsp, perc-biom | dens | decr |

| Hab-EURY | Degree of rheophily (habitat). Fish that exhibit a wide tolerance of flow conditions, although generally not considered to be rheophilic. | hab | ||||

| HabSp-RHPAR | Preference to spawn in running waters. | hab | all except nsp, perc-nsp | |||

| Repro-LITH | Fish spawn exclusively on gravel, rocks, or pebbles. | repro | all | nsp, perc-nsp, perc-dens | biom | decr |

| Atroph-OMNI | Adult consists of more than 25% plant material and more than 25% animal material. Generalists. | troph | ||||

| Atroph-INSV | Insectivorous species. | troph | all | nsp, perc-biom | perc-biom | decr |

Type: biodiv = biodiversity, hab = habitat, repro = reproduction, troph = trophic level, wq = water quality; variants: nsp = number of species, dens = density [Ind/ha], biom = biomass [kg/ha], perc-nsp: number of species of guild in relation to all species, perc-dens = density of guild in relation to all guilds, perc-biom = biomass of guild in relation to all guilds, all = all six variants are included; direction: decr = metric decreases with increasing human pressure; reaction according to our database.

Prediction of fish metrics

We applied a Generalised Linear Model (GLM) for the modelling. For “contentious” metrics (e.g. biomass (kg/ha), density (n/ha) and proportion (percentage)) based on the type of their distributions (e.g. Gaussian or inverse Gaussian) an appropriate link function (e.g. identity, logarithm, power) was selected. Moreover, Poisson distribution and logarithmic link were used to model count data (richness metrics). In addition, an offset was defined by total species number for richness metrics (e.g. EFI+Consortium, 2009) and if these count metrics were over-dispersed, we preferred to choose negative binomial distribution that is a classical alternative to control the over-dispersion in regression analysis of count data (e.g. McCullagh and Nelder, 1989; Logez and Pont, 2011). The square of each explanatory variable was also included to account for potential non-linear relationships (e.g. Moya et al., 2011). The coefficients of the models were estimated at the maximum of likelihood. For each metric, environmental predictor variables were selected using a stepwise procedure based on Akaike's information criterion (AIC; Pont et al., 2006; Logez and Pont, 2011). This procedure selects the combination of variables that minimise the model's AIC.

To evaluate the model performance, R2, standardised residuals and leverage values were extracted. Afterwards, the normality of residuals (using Q–Q plot and histogram), the heteroskedasticity of residuals (graph of standardised residuals versus standardised expected values), the influence of leverage values (graph of residual values versus leverage values), and the relationship between observed and expected values (a linear relation of the form y = x was expected) were visually evaluated. Furthermore, this process was completed by internal-validation based on bootstrapping (Efron and Tibshirani, 1993). Error distribution of each model was estimated by 100 random samples with replacement. The results of internal-validation were observed using histograms of residuals obtained by bootstrap (EFI+Consortium, 2009). Metrics generally matching these criteria were used in the next step.

Standardisation and rescaling of fish metrics

Once the models were fitted, we computed residuals according to Pont et al. (2009) and Logez and Pont (2011) by using the following equation:

| (9) |

where Ri is the residual; Oi is the observed and Ei is the expected value. The value of 1 was added to both observed and predicted values, to handle sites presenting no fish belonging to the metric considered.

Then, the score of each metric (Mi) was obtained by standardising the residuals of the model in the following way:

| (10) |

where Ri is the residual value (difference between observed and expected metric) from sites i to n, M is the median value of the residuals from i to n, Sq is the standard deviation of the residuals in the whole undisturbed dataset.

As standardised residuals vary from −∞ to +∞ and in order to guarantee that each metric varies within a finite interval from 0 to 1, two transformations were applied. All values over a maximum (percentile 95) and below a minimum (percentile 5) were replaced by this maximum (Max) and this minimum (Min). Then the following transformation was applied to each metric score:

| (11) |

Method development step 4: fish metric sensitivity to human pressures

In this step, the sensitivity of the candidate metrics to human pressures was evaluated using the Mann–Whitney U test (Bonferroni-correction; p < 0.05/number of tests) between impaired and reference sites. In addition, reaction of selected metrics to human pressure class was tested by box-plot graphs. Moreover, metrics with a median of reference sites less than 0.80 were rejected as they have lower potential to discriminate between reference and impaired conditions. Afterwards, metrics with high co-linearity were excluded using Spearman's rank correlation test (ρ > |0.80|). In fact, this cut-off was defined in order to keep more variants.

Method development step 5: index calculation, scoring and validation

After selection of final fish metrics, the multi-metric fish index of cyprinid streams (MMICS) was calculated using the arithmetic mean of the standardised and transformed metric scores. We then for the management purposes divided MMICS into five categories (scores) based on the distribution of both impaired and reference sites as done in similar studies (e.g. Schmutz et al., 2007; EFI+Consortium, 2009; Marzin et al., 2014). Class 1 (high) covers lower values of quartile 3 of reference sites as lower boundary and maximum value of reference sites as upper boundary, class 2 (good) lies between the minimum values of reference sites and the upper values of quartile 2 of reference sites, class 3 (moderate) between lower values of quartile 3 of impaired sites and minimum values of reference sites, class 4 (poor) between 0.41 and upper values of quartile 2 of impaired sites and class 5 (bad) between minimum values of impaired sites and 0.40.

In order to detect which specific human pressure types and RPI have the strongest relation with the multi-metric fish index (MMICS), a regression tree test was applied with the multi-metric fish index as dependent variable and the pressure variables (land use, connectivity, morphological, hydrological, water quality and biological pressures plus regional pressure index) as independent variables using the CHAID method in IBM SPSS Statistics 21. The method settings were as follows: 10 times cross validation, maximum tree depth = 3, minimum cases in parent node = 5, minimum cases in child node = 3, adjust significant p-values (p < 0.05/number of tests) and R2 calculated as follows: 1 − (risk estimate value/squared standard deviation displayed at the root node).

The difference between grassland and forest regions was examined by box plot graph and Mann–Whitney U test. Moreover, Spearman's rank correlation test was used to compare fish metrics with specific human pressure types based on the adjusted significant p-value (p < 0.05/number of tests). Finally, for validation of the fish index (MMICS), its independency was examined versus natural environmental predictor variables by linear regression analysis. Moreover, we randomly split the original dataset into two subsets, i.e. 60% (30 reference and 31 impaired sites) and 40% (20 reference and 21 impaired sites). Hereafter, we tested successfully modelled fish metrics versus the human pressures according to the graphical visualisation and Mann–Whitney U test (with Bonferroni-correction) to find the best metrics for the recognition of reference and impaired sites. Afterwards, among the remaining fish metrics, the redundant ones were excluded by Spearman's rank correlation test (ρ > |0.80|). Finally, the fish index developed by remaining metrics in 60% of dataset was validated by 40% dataset versus human pressure class (graphical visualisation) as well as regression test against the regional pressure index.

Results

Human pressure analysis

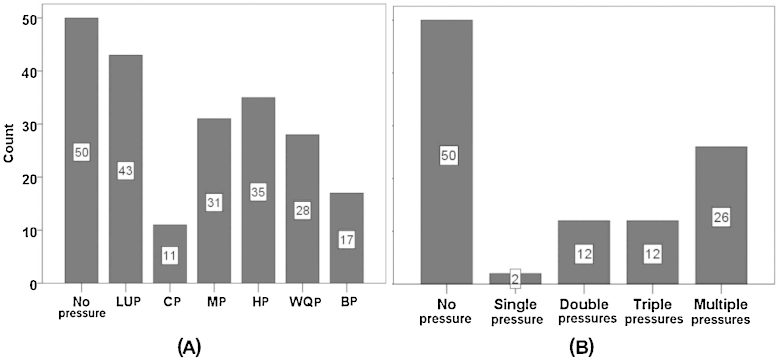

After accounting for redundancy, 20 pressure variables out of 29 remained for further analysis (see Table 1). In our study, the most frequent human pressure was land use (LUP), occurring at 43 sites, in particular urbanisation and agriculture. This was followed by hydrological pressure (HP) at 35 sites, in particular water abstraction (Fig. 3A). In total, 26 sites were affected by multiple pressures, whereas only two sites were influenced by a single pressure. The frequencies of impaired sites by double and triple pressures were the same (12) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

(A) Number of sites regarding no/slight pressure, affected by land use pressure type (LUP), connectivity pressure type (CP), morphological pressure type (MP), hydrological pressure type (HP), water quality pressure type (WQP) and biological pressure type (BP). (B) Number of sites with no, single, double, triple and multiple pressures.

Environmental characteristics and fish assemblages

Environmental characteristics of investigated streams are described in Tables 2 and 3. Using Spearman correlation tests, a co-linearity among some environmental predictor variables (ρ > |0.70|) was found, whereby seven variables, i.e. drainage size, slope, minimum air temperature, range temperature, precipitation, type of major land use/cover (forest/grassland) and ecoregion were finally retained for the modelling process.

22 taxa from six families were identified during the fish sampling, in which Cyprinidae with 14 taxa showed the highest diversity, while Poeciliidae and Salmonidae showed the lowest diversity with one taxon each. Moreover, 19 taxa are native and three are alien. Overall, the studied streams were dominated by cyprinid species more than 70% (Table 4).

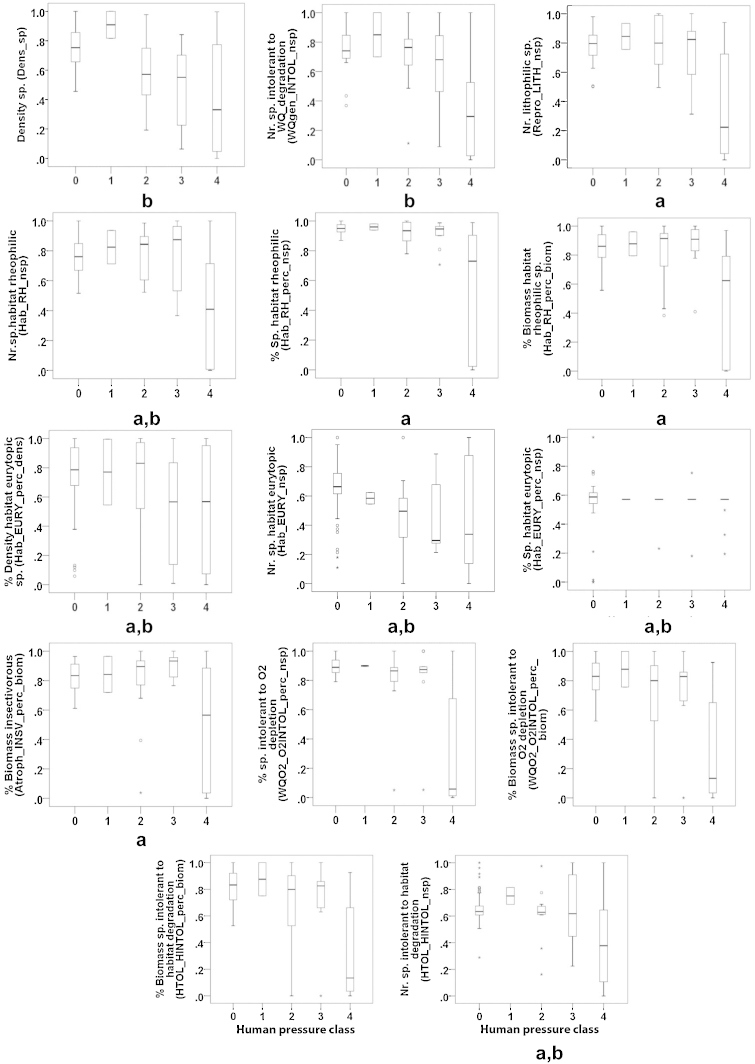

Fish metric selection, MMICS calculation and validation

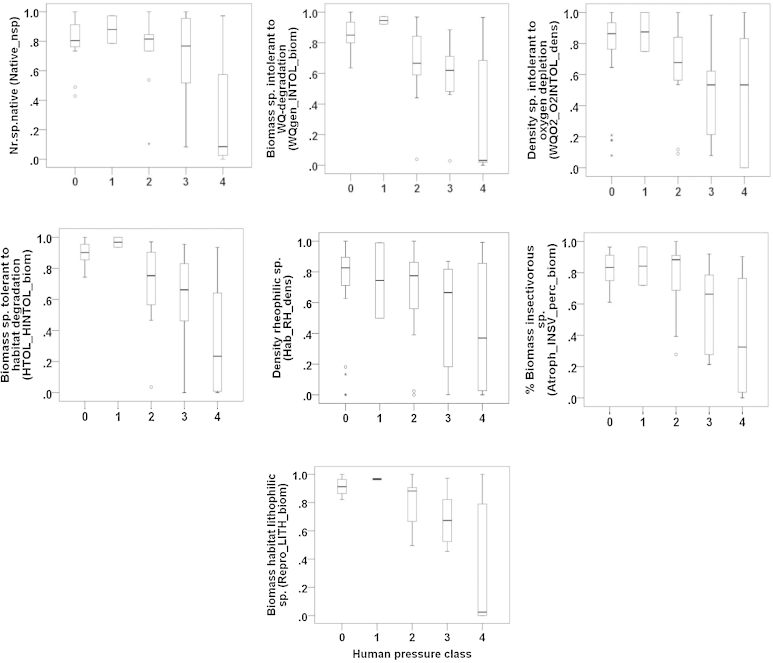

In total, only 39 fish metrics out of 69 fulfilled the selection criteria for modelling (Table 5), of which 14 fish metrics were excluded as they did not show a response to human pressures (Fig. 4 and Table 5). Among those 14 fish metrics, five fish metrics did not show significant differences between impaired and reference sites according to the Mann–Whitney U test (p > 0.0013), and the median of reference sites for seven fish metrics was also less than 0.80 (Fig. 4, see a and b).

Fig. 4.

Box-plot graphs regarding excluded metrics versus human pressure class. “a” shows metrics which did not show significant difference between impaired and reference sites according to Mann–Whitney U test (p > 0.05), “b” shows metrics where the median of reference sites is less than 0.80.

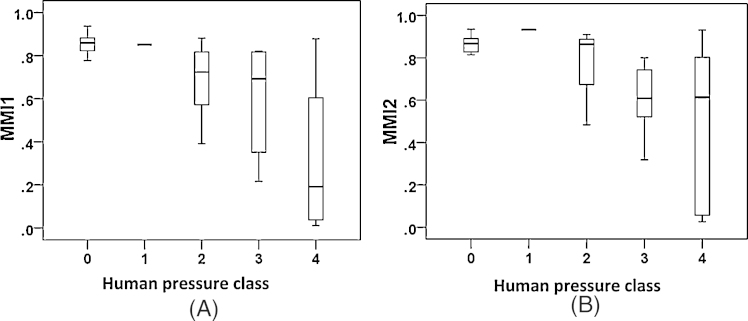

In the next step, the correlation test indicated a high redundancy among the 25 remaining fish metrics (ρ > |0.80|) which is why 18 fish metrics were excluded due to high correlation. Finally, seven fish metrics (number of native species, density of intolerant species to oxygen depletion, biomass of intolerant species to water quality degradation, biomass of intolerant species to habitat degradation, density of rheophilic species, biomass of lithophilic species and percentage biomass of insectivorous species) were chosen as core metrics for the calculation of multi-metric fish index of cyprinid streams (MMICS) (Fig. 5 and Table 5).

Fig. 5.

Box-plot graphs regarding core metrics versus human pressure class.

The coefficients of the core metric models are shown in Table 6. In general, only a few environmental predictor variables were included in the modelling process of each metric. In fact, six metrics with two predictor variables and one metric with three predictor variables were modelled. Slope was the most important variable for five out of seven models (Table 6). In addition, the R2 of these models were higher than 0.35.

Table 6.

Regression coefficients and the criteria selected for the seven models used to model fish assemblages.

| Fish metrics | Intercept | Drainage size | Slope | Tmin | Trange | Precipitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of native species | 1.263 | 0.048 | −0.001 | |||

| Density of intolerant species to oxygen depletion | 5.63 | 0.084 | −0.925 | 1.039 | ||

| Biomass of intolerant species to water quality degradation | 7.001 | −0.281 | 0.899 | |||

| Biomass of intolerant species to habitat degradation | 5.45 | −0.074 | ||||

| Density of rheophilic species | 3.028 | −0.032 | 1.317 | |||

| Biomass of lithophilic species | 4.311 | −0.023 | 0.65 | |||

| Percentage biomass of insectivorous species | 4.287 | 0.055 | −0.001 |

In general, fish metrics did not show pressure specific responses but reacted in a similar way to multiple pressures. Strong reaction is documented for land use, water quality and hydromorphology but not for other pressures (i.e. connectivity and biology) at p < 0.001 level (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Matrix of Spearman rank correlations of specific human pressure types and core metrics. The upper numbers are Spearman correlation coefficients and the lower numbers are p values (number of sites = 102).

| Fish metrics | Land use | Connectivity | Water quality | Hydrology | Morphology | Hydro-morphology (HMC) | Biological pressure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of native species | −.498** | −.114 | −.422** | −.377** | −.418** | −0.303* | −.278* |

| .000 | .254 | .000 | .000 | .000 | 0.047 | .005 | |

| Density of intolerant species to oxygen depletion | −.335* | −.227* | −.421** | −.249* | −.294* | −0.257* | −.018 |

| .001 | .022 | .000 | .012 | .003 | 0.012 | .855 | |

| Biomass of intolerant species to water quality degradation | −.641** | −.147 | −.544** | −.499** | −.567** | −0.404* | −.298* |

| .000 | .140 | .000 | .000 | .000 | 0.028 | .002 | |

| Biomass of intolerant species to habitat degradation | −.640** | −.145* | −.545** | −.496** | −.565** | −0.402* | −.295* |

| .000 | .035 | .000 | .000 | .000 | 0.012 | .003 | |

| Density of rheophilic species | −.527** | −.275* | −.471** | −.398** | −.403** | −0.359* | −.157 |

| .000 | .005 | .000 | .000 | .000 | 0.002 | .115 | |

| Biomass of lithophilic species | −.650** | −.054 | −.623** | −.444** | −.492** | −0.330* | −.338* |

| .000 | .587 | .000 | .000 | .000 | 0.042 | .001 | |

| Percentage biomass of insectivorous species | −.483** | −.308* | −.391** | −.423** | −.390** | −0.374* | −.149 |

| .000 | .002 | .000 | .000 | .000 | 0.001 | .134 |

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed).

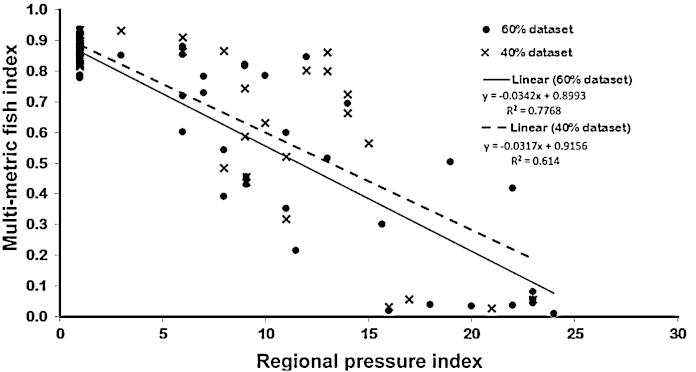

After splitting the original dataset into two subsets for the validation of fish index (MMICS), it was observed that the same fish metrics remained again for the calculation of the fish index. Moreover, the reactions of the developed fish indices (MMI1 and MMI2) from 60% and 40% datasets versus human pressure class and regional pressure index (RPI) were consistent (Figs. 6A and B and 7).

Fig. 6.

Box-plot graphs regarding multi-metric fish indices (MMI1: 60% dataset, A; MMI2: 40% dataset, B) versus human pressure class.

Fig. 7.

Regression of multi-metric fish index of 60% and 40% dataset versus regional pressure index (RPI).

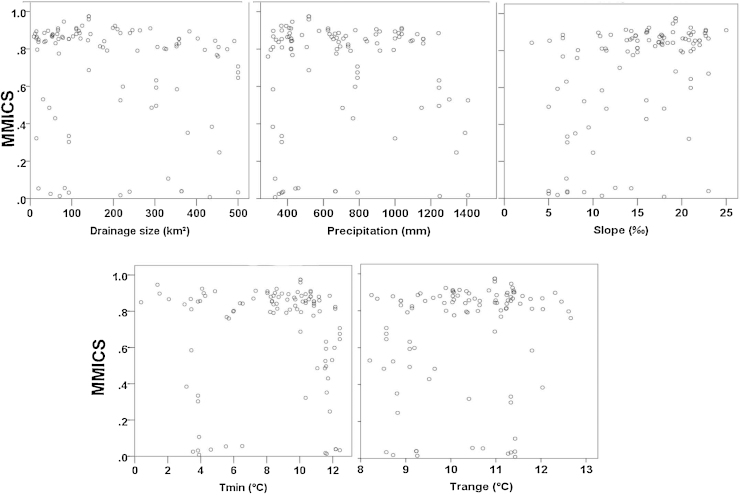

Stepwise linear regression between the multi-metric fish index of original dataset (MMICS) and environmental predictor variables (drainage size, slope, minimum air temperature, range temperature and precipitation) showed that none of the environmental variables was retained and the variability in this index (MMICS) explained by these environmental variables was not significant (p > 0.05) (see also Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Multi-metric fish index of original dataset (MMICS) versus environmental predictor variables.

The regression tree showed the best relation between the regional pressure index (RPI) and the multi-metric fish index (MMICS) in comparison to the other human pressure types (R2 = 0.75, p = 0.000).

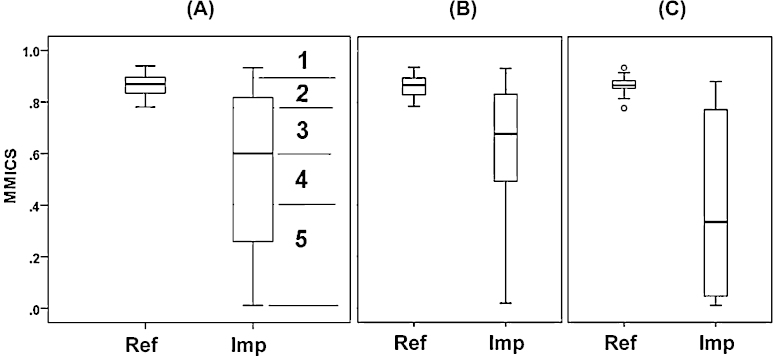

Further, the MMICS was divided into five categories (scores), based on the distribution of both impaired and reference sites (Fig. 9A): Class 1 (high) covers values between 0.90 and 1.00, class 2 (good) values between 0.78 and 0.89, class 3 (moderate) values between 0.61 and 0.77, class 4 (poor) values between 0.41 and 0.60 and class 5 (bad) values between 0.00 and 0.40. Overall, among 52 impaired sites, 35 sites are in a moderate, poor or bad status, i.e. there is strong need for restoration actions.

Fig. 9.

Classification of the multi-metric fish index of original dataset (MMICS) into five categories on the basis of observed scores at reference and impaired sites (A). Multi-metric fish index of original dataset (MMICS) regarding reference (Ref) and impaired (Imp) sites in forest (B) and grassland (C) regions.

The comparison of the MMICS in grassland and forest regions also displayed that the index in the impaired grassland sites is significantly lower than in the forest region (Fig. 9B and C).

Discussion

In Iran, similar to Europe and elsewhere, there are numerous human alterations and pressures directly affecting the physicochemical conditions of running waters and strongly influencing aquatic biota (e.g. Kiabi et al., 1999; Abdoli, 2000; Abdoli and Naderi, 2009; Esmaeili et al., 2007; Mostafavi et al., 2014). Multi-metric fish indices, like the one we developed, are powerful tools for the ecological assessment of streams (e.g. Pont et al., 2006, 2009; Schmutz et al., 2007; Meador et al., 2008; Ruaro and Gubiani, 2013).

Human pressures

The intensity of pressures in our study is higher compared to studies from Europe (Schinegger et al., 2012) because most sites are affected by multiple pressures indicating high potential of stress for fish.

Land use pressures

Akhani et al. (2010) indicated that half of the forest in the Caspian Sea Basin was eradicated in recent decades (from 3.6 million to 1.8 million hectares). In contrast, the extent of agriculture and build-up areas increased. This finding is mirrored by our data as most sites were affected by land use pressures (43 out of 52 impaired sites). Moreover, an increase of land use pressure is often accompanied by an increase of hydrology, morphology and water quality pressures (Osborne and Wiley, 1988), which is inline with our results, as 35 out of 52 sampling sites were impaired by hydrological alteration, 31 by morphological alteration and 28 by water quality problems.

Hydrological pressures

Water abstraction is one of the most important hydrological pressures according to our findings. Water is abstracted for the purpose of agricultural irrigation via establishment of dams as well as direct water abstraction from streams by artificial channels and pumps. Some rivers and streams have no flowing water for some months of the year, or flows are reduced to only a fraction of their original magnitude (often observed during our monitoring and even the flow velocity of some sampling sites was zero). It was also observed that water abstraction influenced water quality of rivers via reduction of flow velocity, the habitat quality (water depth, wetted width) and connectivity (including lateral connectivity and drying up of side arms). All these findings are in agreement with other studies (e.g. Bernardo et al., 2003; Meador and Carlisle, 2007).

In this regard, almost all core metrics except density of intolerant species to oxygen depletion showed a negative response to hydrological pressures (dominated by water abstraction pressure). This is more or less in accordance with a study of Benejam et al. (2009), where number of intolerant species, proportion of intolerant individuals, number of benthic species, number of families, number of native species and number of insectivore species showed significant response to water abstraction. Although tolerant species are not included in our core metrics, we observed tolerant species (e.g. Pseudorasbora parva, Carassius carassius, Gambusia holbrooki) in the affected sites.

Connectivity pressures

To our knowledge, almost all rivers of the Caspian Sea Basin are disconnected from the sea due to ground sills (with drops up to 1.5 m for the establishment of bridges) or/and dams. Due to the mentioned connectivity barriers, no long-distance migratory species (e.g. Acipenser sp., C. wagneri, Rutilus caspicus, Rutilus rutilus) were observed in our study sites, while these species have been reported in many of the sampled rivers in the past (e.g. Berg, 1948–1949; Rostami, 1961; Holčík and Oláh, 1992; Abdoli, 2000; Mostafavi, 2007; Abdoli and Naderi, 2009; Coad 2014). Consequently, our fish index was not designed for long-distance migratory fish species and therefore it is not applicable for this purpose. Future IBIs should incorporate the loss of long-distance migratory species, e.g. based on historical data in order to fully reflect the pressure of continuity disruptions at the catchment level.

In our study, connectivity pressures were not correlated with any metrics while Schmutz et al. (2007) indicated that insectivorous, omnivorous, intolerant and lithophilic metrics showed positive response (increase) to connectivity disruptions in the European rivers. This difference might be related to the fact that European rivers are affected by a different combination of pressures, e.g. a higher proportion of dammed rivers, however, this should be studied in more detail in future studies in Iran.

Water quality pressures

According to our study, observed water quality pressures are mostly related to untreated sewage of cities and agriculture for the recent decades. Water pollution was not a major problem before 1960s because of the underdeveloped state of cities, industry and agriculture (Coad, 1980).

We observed that the “jube” system, i.e. a series of channels carrying water along the streets of most towns and cities, is also a source of pollution. It functions to irrigate roadside trees but also serves to carry away detergents and other pollutants, which may be poured into the nearest river or stream (indicated also by Coad, 1980 and Mostafavi, 2007). In addition, we observed that the effluent of agriculture and some livestock, factories, slaughter houses, hospitals, restaurants, etc. is directly discharged into rivers without any treatment. Agricultural effluents also contain high levels of phosphate, nitrogen, potash and pesticides which is inline with our study as measured parameters like NO2−, NO3− and PO43− reached up to 0.17, 9.60 and 5.70 mg/l respectively in some impaired sites. Consequently, the richness and abundance of sensitive or intolerant species like B. lacerta, Luciobarbus mursa, S. trutta were severely reduced or these species even disappeared entirely in some sites. Conversely, the abundance of some tolerant species like P. parva, C. carassius, G. holbrooki increased. Moreover, all core metrics in our study showed very significant and negative correlation with this type of pressure. This is consistent with Schmutz et al. (2007), who indicated that insectivorous, intolerant and lithophilic species exclusively responded (decreased) to water quality pressures. Furthermore, Schinegger et al. (2013) pointed out that intolerant, rheoparous, tolerant and omnivorous species showed significant reaction to this pressure type. In comparison with them, richness and intolerant metrics are inline with our study, but other metrics were excluded in the modelling process and correlation test. However, omnivorous species (e.g. P. parva, C. carassius, G. holbrooki) were observed in sites with this type of pressure and rheoparous species also showed negative reaction but was left out due to correlation with other metrics.

Morphological pressures

Based on our observation, channelisation is one of the main morphological pressures in this area which is generally linked to farmland acquisition, construction of bridges or roads, flood prevention as well as river bed and bank erosion control.

Moreover, gravel mining and sand extraction are other main drivers for morphological pressures, changing the stream's physical habitat characteristics and leading to e.g. siltation, clogging of the riverbed, turbidity and degradation of the riparian vegetation (Lau et al., 2006; Padmalal et al., 2008; Paukert et al., 2011). The intensity of this pressure in some rivers we sampled is very high and the associated fine sediment inputs result in high turbidity (values up to 1185 NTU were observed). Based on our results, almost all core metrics except intolerance of species (density) to oxygen depletion showed significant correlation to this pressure type. Schmutz et al. (2007) and Schinegger et al. (2013) combined morphology, hydrology and connectivity pressure types into one type named hydro-morphology (HMC), which we also considered. In Schmutz et al. (2007) only insectivorous, intolerant and lithophilic metrics exclusively responded to the hydromorphological pressures, in Schinegger et al. (2013) only richness, intolerant, tolerant and rheoparous metrics while in our study any metric responded to these combined pressures at the p < 0.001 level.

Other biological pressures

Actually, overexploitation and unusual methods of fishing such as using cast net, electricity, toxics and dynamite are the other known threats based on our study and others (Abdoli, 2000; Esmaeili et al., 2007). Overall, out of our seven core metrics, only four were correlated to this pressure type. Most likely, this variation is due to the fact that biological pressures are rare in our dataset. Therefore, this aspect should be investigated in further studies.

Applicable fish metrics as well as showing a response to specific human pressures

Our index involved five (out of six) structural and functional types of metrics related to biodiversity, habitat, reproduction, trophic level and water quality. These should foster the robustness of our index, as such traits are sensitive to human pressures and are comparable among assemblages even across ecoregions that differ in their taxonomic composition (e.g. Statzner et al., 2001; Moya et al., 2011).

Moreover, according to regression tree result, RPI had the strongest relation with MMICS in comparison with other pressure types. It can be true because most sites were affected by different pressure types and RPI actually evaluated both pressure intensity and multiple pressure effects on sampling sites.

The fish index (MMICS) of impaired sites in the grassland region was significantly lower than in the forest region. Most likely, the reason is that the severity of water abstraction pressure was higher in the grassland region. Consequently, the effects of other pressures are intensified in that region.

According to our dataset, all core metrics showed significant reaction to most pressure types, but specific metrics for specific pressure types were not generally found, as e.g. described by Schinegger et al. (2013). However, this hypothesis should be tested with a larger dataset in future.

Uncertainty in the application of a multi-metric fish index (MMICS)

Our fish index is recommended for wadeable streams in the cyprinid zone with slope between 3% and 25%, wetted width less than 20 m and drainage size less than 500 km2. To date, 116 species have been recorded from the southern part of the Caspian Sea Basin, belonging to Iranian territory (Esmaeili et al., 2014). In our study, 22 taxa were recorded indeed. This difference is due to several reasons. First, 27 of 119 species are occurring only in the marine section of the Caspian Sea Basin, but not in the rivers. Second, 18 species are migratory ones and due to connectivity pressures they are not able to reach the spawning habitats generally (Abdoli and Naderi, 2009; Kiabi et al., 1999). Third, our sampling sites were limited to certain areas (as stated before, e.g. regarding slope, catchment size, river width and being wadeable), therefore, some species like Pelecus cultratus, Aspius aspius, Tinca tinca, Vimba persa, Liza saliens, Esox lucius, etc. were not included in our study. Finally we did not cover the whole basin, one ecoregion (Turan Plain) was not considered in our study. Nevertheless, our findings are defensible, as our study covers the most common species (e.g. Abdoli and Naderi, 2009; Esmaeili et al., 2010, 2014; Coad, 2014).

Abundance of individual species may vary seriously over time (Lyons, 2006). Therefore, this fish index is only applicable for data collected during autumn. In addition, the sampling method is particularly important because sampling efficiency and sampling effort strongly influence the fish index scores (e.g. Simon and Sanders, 1999). As currently, the method for fish sampling in Iran is not standardised, we strongly recommend using European standards, as e.g. CEN (2003), or even CEN standard.

Conclusion

Our index performed well in discriminating between reference and impaired sites, showing a significant negative linear response along a gradient of human pressures independent of natural environmental variability. Overall, the development of such an index offers the opportunity to enhance national bio-monitoring programmes in Iran by considering also variables like geology and physical habitat structure as well as to adjust the CEN standard for the Iranian waters for more precise sampling methods.

Acknowledgements

Part of this work was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, Predictive Index of Biotic Integrity for running waters of Iran, contract number P 23650-B17). The Ministry of Sciences, Technology of Iran awarded a scholarship to Hossein Mostafavi (first author). Special thanks are given to Majid Bakhtiyari, Houman Liaghati, Bahram Kiabi, Asghar Abdoli, Henrik Majnonian, Hamid Reza Esmaeili, Ahmad Reza Mehrabian, Florian Pletterbauer, Clemens Trautwein, Saber Vatandost, Azad Teimori, Mehrgan Ebrahimi, Ebrahim Fataei, Keyvan Abbasi, Gholamreza Amiri Ghadi, Hamid Reza Bagherpour, and Arash Arsham for their support in the process of this study. We are very thankful to the Environment Department of Iran and its affiliated institutions in Tehran, Mazandaran, Gilan, Ardabil and East Azerbaijan and their employees Ahmad Reza Lahijanzadeh, Dariush Moghadas, Amir Abdoos, Hossein Deghani, Ebrahim Rahimi, Mohamad Mirzaei, Hossein Alinejad, Behrouz Afkhami and many others. We also thank Erika Thaler for editing the text.

References

- Abdoli A. Iranian Museum of Nature and Wildlife; Tehran: 2000. The Inland Water Fishes of Iran. [Google Scholar]

- Abdoli A., Naderi M. Abzian Scientific Publications; Tehran: 2009. Biodiversity of Fishes of the Southern Basin of the Caspian Sea. [Google Scholar]

- Abell R., Thieme M.L., Revenga C., Bryer M., Kottelat M., Bogutskaya N., Coad B., Mandrak N., Balderas S.C., Bussing W., Stiassny M.L.J., Skelton P., Allen G.R., Unmack P., Naseka A., Ng R., Sindorf N., Robertson J., Armijo E., Higgins J.V., Heibel T.J., Wikramanayake E., Olson D., López H.L., Reis R.E., Lundberg J.G., Sabaj Pérez M.H., Petry P. Freshwater ecoregions of the world: a new map of biogeographic units for freshwater biodiversity conservation. Bioscience. 2008;58:403–414. [Google Scholar]

- Akhani H., Djamali M., Ghorbanalizadeh A., And E.R. Plant biodiversity of Hyrcanian relict forests, North of Iran: an overview of the flora, vegetation, palaeoecology and conservation. Pak. J. Bot. 2010;42:231–258. [Google Scholar]

- Angermeier P., Davideanu G. Using fish communities to assess streams in Romania: initial development of an index of biotic integrity. Hydrobiologia. 2004;511:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Angermeier P.L., Smogor R.A., Stauffer J.R. Regional frameworks and candidate metrics for assessing biotic integrity in mid-Atlantic highland streams. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2000;129:962–981. [Google Scholar]

- Benejam L., Aparicio E., Vargas M.J., Vila-Gispert A., García-Berthou E. Assessing fish metrics and biotic indices in a Mediterranean stream: effects of uncertain native status of fish. Hydrobiologia. 2009;603:197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Berg L.S. vol. 3. Israel Program for Scientific Translations; Jerusalem: 1948–1949. pp. 1962–1965. (Freshwater Fishes of the USSR and Adjacent Countries). [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo J.M., Ilheu M., Matono P., Costa A.M. Interannual variation of fish assemblage structure in a Mediterranean River: implications of streamflow on the dominance of native or exotic species. River Res. Appl. 2003;19:521–532. [Google Scholar]

- Buisson L., Blanc L., Grenouillet G. Modelling stream fish species distribution in a river network: the relative effects of temperature versus physical factors. Ecol. Freshw. Fish. 2008;17:244–257. [Google Scholar]

- CEN . European Committee for Standardization; Brussels: 2003. Water Quality – Sampling of Fish with Electricity. European Standard – EN 14011:2003. [Google Scholar]

- Coad B.W. Environmental change and its impact on the freshwater fishes of Iran. Biol. Conserv. 1980;19:51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Coad B.W. Coad B.W.; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: 2014. Freshwater Fishes of Iran.http://www.briancoad.com [Google Scholar]

- Coad B.W., Vilenkin B.Y. Co-occurrence and zoogeography of the freshwater fishes of Iran. Zool. Middle East. 2004;31:53–62. [Google Scholar]

- de Jager A.L., Vogt J.V. Development and demonstration of a structured hydrological feature coding system for Europe. Développement et implémentation d’un système de codification d’entités hydrologiques structurées en EuropeHydrol. Sci. J. 2010;55:661–675. [Google Scholar]

- Degerman E., Beier U., Breine J., Melcher A., Quataert P., Rogers C., Roset N., Simoens I. Classification and assessment of degradation in European running waters. Fish. Manage. Ecol. 2007;14:417–426. [Google Scholar]

- EFI+Consortium . 2009. Manual for the application of the new European Fish Index EFI+. A fish-based method to assess the ecological status of European running waters in support of the Water Framework Directive.http://efi-plus.boku.ac.at [Google Scholar]

- Efron B., Tibshirani R. Chapman and Hall; London: 1993. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili H.R., Teimori A., Khosravi A.R. A note on the biodiversity of Ghadamghah spring–stream system in Fars province, southwest Iran. Iran. J. Anim. Biosyst. 2007;3:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili H.R., Coad B.W., Gholamifard A., Nazari N., Teimori A. Annotated checklist of the freshwater fishes of Iran. Zoosyst. Rossica. 2010;19:361–386. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili H.R., Coad B.W., Mehraban H.R., Masoudi M., Khaefi R., Abbasi K., Mostafavi H., Vatandoust S. An updated checklist of fishes of the Caspian Sea basin of Iran with a note on their zoogeography. Iran. J. Ichthyol. 2014;1:152–184. [Google Scholar]

- Filipe A.F., Markovic D., Pletterbauer F., Tisseuil C., De Wever A., Schmutz S., Bonada N., Freyhof J. Forecasting fish distribution along stream networks: brown trout (Salmo trutta) in Europe. Divers. Distrib. 2013;19:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ganasan V., Hughes R.M. Application of an index of biological integrity (IBI) to fish assemblages of the rivers Khan and Kshipra (Madhya Pradesh), India. Freshw. Biol. 1998;40:367–383. [Google Scholar]

- Hering D., Borja A., Carstensen J., Carvalho L., Elliott M., Feld C.K., Heiskanen A.S., Johnson R.K., Moe J., Pont D., Solheim A.L., de Bund W.v. The European Water Framework Directive at the age of 10: a critical review of the achievements with recommendations for the future. Sci. Total Environ. 2010;408:4007–4019. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans R.J., Cameron S.E., Parra J.L., Jones P.G., Jarvis A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005;25:1965–1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans R.J., Cameron S.E., Parra J.L. Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California; 2007. WorldClim Version 1.4. Available at http://www.worldclim.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Holčík J., Oláh J. Food and Agriculture Organization; Rome: 1992. Fish, Fisheries and Water Quality in Anzali Lagoon and Its Watershed. Report Prepared for the Project – Anzali Lagoon Productivity and Fish Stock Investigations. FI:UNDP/IRA/88/001 Field Document 2, x + 109 pp. http://www.iucnredlist.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Hughes R., Larsen D., Omernik J. Regional reference sites: a method for assessing stream potentials. Environ. Manage. 1986;10:629–635. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes R.M., Kaufmann P.R., Herlihy A.T., Kincaid T.M., Reynolds L., Larsen D.P. A process for developing and evaluating indices of fish assemblage integrity. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1998;55:1618–1631. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes R.M., Howlin S., Kaufmann P.R. A biointegrity index (IBI) for coldwater streams of western Oregon and Washington. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2004;133:1497–1515. [Google Scholar]

- Hugueny B., Camara S., Samoura B., Magassouba M. Applying an index of biotic integrity based on fish assemblages in a West African river. Hydrobiologia. 1996;331:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y.T., Chen Y.F. River health assessment in a large river: bioindicators of fish population. Ecol. Indic. 2013;26:24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kamali M., Esmaeili A. Biomonitoring of Lasem River (Amol-Mazandaran province) based on the macro-inverteberate. J. Olom Zisti Vahed Lahijan. 2009;1:51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Karr J.R. Assessment of biotic integrity using fish communities. Fisheries. 1981;6:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Karr J.R., Chu E.W. Island Press; Washington, DC: 1999. Restoring Life in Running Waters: Better Biological Monitoring. [Google Scholar]

- Kiabi B.H., Abdoli A., Naderi M. Status of the fish fauna in the South Caspian Basin of Iran. Zool. Middle East. 1999;18:57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Langdon R.W. A preliminary index of biological integrity for fish assemblages of small cold water streams in Vermont. Northeast. Nat. 2001;8:219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Lau J.K., Lauer T.E., Weinman M.L. Impacts of channelization on stream habitats and associated fish assemblages in east central Indiana. Am. Midl. Nat. 2006;156:319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Liu K., Zhou W., Li F.L., Lan J.H. A fish-based biotic integrity index selection for rivers in Hechi Prefecture, Guangxi and their environmental quality assessment. Zool. Res. 2010;31:531–538. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1141.2010.05531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logez M., Pont D. Development of metrics based on fish body size and species traits to assess European coldwater streams. Ecol. Indic. 2011;11:1204–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Logez M., Bady P., Pont D. Modelling the habitat requirement of riverine fish species at the European scale: sensitivity to temperature and precipitation and associated uncertainty. Ecol. Freshw. Fish. 2012;21:266–282. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons J. A fish-based index of biotic integrity to assess intermittent headwater streams in Wisconsin, USA. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2006;122:239–258. doi: 10.1007/s10661-005-9178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majnonian H., Kiabi B.H., Danesh M. Sazman hefazat mohit zist Iran (Department of Environment of Iran); Dayereh Sabz, Tehran: 2005. Reading in Zoogeography of Iran, Part 1. [Google Scholar]

- Marzin A., Archaimbault V., Belliard J., Chauvin C., Delmas F., Pont D. Ecological assessment of running waters: do macrophytes, macroinvertebrates, diatoms and fish show similar responses to human pressures? Ecol. Indic. 2012;23:56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Marzin A., Delaigue O., Logez M., Belliard J., Pont D. Uncertainty associated with river health assessment in a varying environment: the case of a predictive fish-based index in France. Ecol. Indic. 2014;43:195–204. [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh P., Nelder J.A. Chapman and Hall/CRC; London: 1989. Generalized Linear Models. [Google Scholar]

- Meador M.R., Carlisle D.M. Quantifying tolerance indicator values for common stream fish species of the United States. Ecol. Indic. 2007;7:329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Meador M.R., Whittier T.R., Goldstein R.M., Hughes R.M., Peck D.V. Evaluation of an index of biotic integrity approach used to assess biological condition in western U.S. streams and rivers at varying spatial scales. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2008;137:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafavi H. Fish biodiversity in Talar River, Mazandaran Province. Iran. J. Environ. Stud.Majale olom mohity. 2007;32:127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafavi H., Babaii S., Mahmoudi H. Environmental Sciences Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University; Tehran: 2004. Assembling of Preliminary Report on Natural Potentialities in Mazndaran Province at Its Present Condition. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafavi H., Pletterbauer F., Coad B.W., Mahini A.S., Schinegger R., Unfer G., Trautwein C., Schmutz S. Predicting presence and absence of trout (Salmo trutta) in Iran. Limnol.: Ecol. Manage. Inland Waters. 2014;46:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.limno.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafavi, H., Schinegger, R., Melcher, A., Bakhtiyari, M., Trautwein, C., Pletterbauer, F., Unfer, G., Schmutz, S., 2014 A new fish based multi-metric assessment index for cold-water streams in the Iranian Caspian Sea Basin (submitted for publication).

- Moya N., Hughes R.M., Domínguez E., Gibon F.-M., Goitia E., Oberdorff T. Macroinvertebrate-based multimetric predictive models for evaluating the human impact on biotic condition of Bolivian streams. Ecol. Indic. 2011;11:840–847. [Google Scholar]

- Noble R.A.A., Cowx I.G., Starkie A. Development of fish-based methods for the assessment of ecological status in English and Welsh rivers. Fish. Manage. Ecol. 2007;14:495–508. [Google Scholar]

- Oberdorff T., Pont D., Hugueny B., Chessel D. A probabilistic model characterizing fish assemblages of French rivers: a framework for environmental assessment. Freshw. Biol. 2001;46:399–415. [Google Scholar]

- Oberdorff T., Pont D., Hugueny B., Porcher J.P. Development and validation of a fish-based index for the assessment of ‘river health’ in France. Freshw. Biol. 2002;47:1720–1734. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne L.L., Wiley M.J. Empirical relationships between land use/cover and stream water quality in an agricultural watershed (US) J. Environ. Manage. 1988;26:9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Padmalal D., Maya K., Sreebha S., Sreeja R. Environmental effects of river sand mining: a case from the river catchments of Vembanad lake, Southwest coast of India. Environ. Geol. 2008;54:879–889. [Google Scholar]

- Paukert C.P., Pitts K.L., Whittier J.B., Olden J.D. Development and assessment of a landscape-scale ecological threat index for the Lower Colorado River Basin. Ecol. Indic. 2011;11:304–310. [Google Scholar]

- Pont D., Hugueny B., Beier U., Goffaux D., Melcher A., Noble R., Rogers C., Roset N., Schmutz S. Assessing river biotic condition at a continental scale: a European approach using functional metrics and fish assemblages. J. Appl. Biol. 2006;43:70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pont D., Hughes R.M., Whittier T.R., Schmutz S. A predictive index of biotic integrity model for aquatic-vertebrate assemblages of western U.S. streams. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2009;138:292–305. [Google Scholar]

- Qadir A., Malik R.N. Assessment of an index of biological integrity (IBI) to quantify the quality of two tributaries of river Chenab, Sialkot, Pakistan. Hydrobiologia. 2009;621:127–153. [Google Scholar]