Abstract:

Introduction:

Domperidone is a dopamine receptor antagonist with peripheral prokinetic and central antiemetic properties. Prolongation of the QTc interval with chronic use of oral domperidone in standard doses has been reported in the literature. Our goal was to investigate cardiac toxicity in patients receiving 2-fold greater doses than in previous reports.

Methods:

A retrospective chart review was conducted of patients with nausea (N) and vomiting (V) receiving domperidone from 2009 to 2013 under an Investigational New Drug (IND) protocol. Patient demographics, indications for therapy, clinical outcomes, cardiac symptoms and electrocardiogram tracings were reviewed. Prolonged QTc was verified if >470 milliseconds in females (F) and >450 milliseconds in males (M).

Results:

A total of 64 patients, 44 female (37% Hispanic, 60% white, 3% African American), were taking domperidone for diabetic gastroparesis 45%; idiopathic gastroparesis 36%; chronic N&V 8%; dumping syndrome 5%; cyclic vomiting 5% and conditioned vomiting 1%. Mean duration of therapy was 8 months (range, 3 months to 4 years). Doses ranged from 40 to 120 mg/d with 90% receiving 80 to 120 mg compared with the standard dose of 40 mg. Of note, 73% of subjects benefited from treatment with reduced nausea and vomiting. Thirty-seven patients had follow-up electrocardiograms available, and they showed that the mean QTc at baseline was 424 milliseconds ± 28.4 (SD) compared with 435 milliseconds ± 27.2 (SD) at follow-up (not significant). Ten of these patients had prolonged QTc at F/U ranging from 453 to 509 milliseconds, without any cardiovascular complaints. There was no relationship between prolonged QTc and daily dose of domperidone, body mass index or age.

Conclusions:

Our data indicate that at very high dosing, the prokinetic/antiemetic agent domperidone has a low risk of adverse cardiovascular events while exhibiting good clinical efficacy.

Key Indexing Terms: Domperidone, Gastroparesis, Nausea and Vomiting, QTc interval, Prokinetic

Domperidone and metoclopramide are dopamine antagonists with a strong affinity for dopamine receptors in the central as well as peripheral nervous systems, and specifically, the gastrointestinal tract. These agents act as antiemetics at the chemoreceptor trigger zone and as a prokinetics in the upper gastrointestinal tract to accelerate gastric emptying. Metoclopramide is currently the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved prokinetic agent in the United States. The major drawback is that it readily crosses the blood-brain barrier resulting in central nervous system side effects in up to 40% of patients ranging from somnolence to extrapyramidal symptoms as well as Parkinsonism and rarely tardive dyskinesia. However, domperidone poorly penetrates the blood-brain barrier but maintains a powerful antiemetic effect at the chemoreceptor trigger zone level as well as its peripheral prokinetic properties. Domperidone is especially useful in the management of the upper gastrointestinal motility disorder, gastroparesis, when patients have failed or cannot tolerate metroclopramide treatment. It is also considered a safer alternative to metoclopramide for individuals who will require long-term therapy for upper gastrointestinal motility problems where nausea and vomiting are prominent.

Domperidone was first synthesized in 1974, and it has been approved for patient use throughout the world with specific clinical applications in gastroparesis, gastroesophageal reflux disease and as a general antiemetic. This agent is currently available on the worldwide market but not in the United States. In the past 20 years in the United States, domperidone has only been available through an FDA-approved Limited Access Program. Domperidone can be prescribed by physicians who apply for an Investigational New Drug (IND) protocol to provide this drug to their patients with gastroparesis or other functional gastrointestinal disorders associated with nausea and vomiting that are refractory to or unable to tolerate the current standard therapy. Domperidone was not approved for use in the United States based on the FDA requirements for further investigation with large clinical trials to better ascertain its efficacy and safety.

The QT interval is the measure of time between the onset of ventricular depolarization and completion of ventricular repolarization. A prolonged QT interval is thus considered a predictive noninvasive risk factor for sudden cardiac death (SCD) since a delay in ventricular repolarization can provoke arrhythmias, such as ventricular fibrillation and torsade de pointes. Domperidone has been described to inhibit the human Ether-a-go-go-Related Gene (hERG), which encodes a delay in the rectifier potassium current leading to a prolongation of cardiac repolarization.1,2 Domperidone is mainly metabolized through CYP3A4. As a result, CYP3A4 inhibitors may increase the plasma concentration of domperidone by blocking its metabolism, increasing the possibility of a cardiac dysrhythmia.3

There have been reports in Europe of prolongation of QTc intervals with chronic use of oral domperidone raising the question of potential ventricular arrhythmias and/or SCD.4–7 Most of the evidence in regards to the cardiotoxicity of the drug was related to the intravenous form of domperidone, which is no longer marketed or available.8 No studies have been performed in the United States to investigate the correlation of oral domperidone dosage and the development of cardiovascular (CV) adverse effects.

According to the medical literature, the typical dose of domperidone is 10 mg 3 or 4 times per day.9,10 However, patients accessing domperidone through the FDA-approved IND protocol can receive doses ranging up to 120 mg per day. The lack of any comprehensive research regarding the dosage of oral domperidone and its cardiotoxicity prompted us to further investigate this relationship. The authors analyzed the clinical efficacy, possible cardiac-related adverse events and the electrocardiogram (ECG) findings during domperidone therapy to determine whether any cardiotoxicity occurred in patients receiving chronic high doses of domperidone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The authors performed a retrospective chart review of patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms referred to a single physician who had a domperidone IND: Limited Access Program approval for investigational use of domperidone at a tertiary GI Motility Center. A protocol designed by the FDA was in turn approved by the Texas Tech University Health Science Center Institutional Review Board and an informed consent was obtained from each patient for the use of domperidone in this study. The data collected included patient demographics, gastrointestinal diagnosis, clinical indications for the use of domperidone, dosage, frequency and adverse effects related to domperidone therapy. The authors specifically focused on identifying any CV complaints as well as analyzing ECG findings in patients on domperidone therapy. The clinical outcome was assessed for each patient during their follow-up visits in the clinic of the physician with the IND (R.W.M.), and it was recorded in the medical records. Patient satisfaction in relation to their gastrointestinal symptoms was assessed using a 7-point Likert's scale: (markedly worse, moderately worse, mildly worse, unchanged, mildly improvement, moderately improvement, markedly better), which is a widely used tool to assess changes of subjective symptoms over time. Complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, magnesium and prolactin were drawn before starting the drug and on follow-up visits.

ECG Interpretation and Measurement

An ECG was obtained at baseline per protocol and on each subsequent visit. A 12-lead resting ECG was recorded and stored digitally. The QT interval was determined at the start of the QRS complex until the end of the T-wave. The absolute value of the measured QT (QTm) interval should be corrected by heart rate. This is because the QT interval can change in relation to the heart rate. For example, in tachycardia, the absolute measure of QT will be shorter as a consequence of the shorter action potential.11 To adjust for heart rate, the Bazett formula  was used.11 Bazett's QT correction is not suitable when heart rate is less than 60 or more than 100 beats per minute. The QTc interval at the time of the first visit was taken as the independent variable. For those participants who also had a second and subsequent ECG at follow-up visits, the results of follow-up QTc interval measurements were included in the analyses. A prolonged QTc based on the FDA Investigational protocol definition is defined as more than 470 milliseconds in females and more than 450 milliseconds in males.12–14 Patients who had a prolonged QTc at baseline were not included in the study and did not receive domperidone.

was used.11 Bazett's QT correction is not suitable when heart rate is less than 60 or more than 100 beats per minute. The QTc interval at the time of the first visit was taken as the independent variable. For those participants who also had a second and subsequent ECG at follow-up visits, the results of follow-up QTc interval measurements were included in the analyses. A prolonged QTc based on the FDA Investigational protocol definition is defined as more than 470 milliseconds in females and more than 450 milliseconds in males.12–14 Patients who had a prolonged QTc at baseline were not included in the study and did not receive domperidone.

Statistical Analysis

All results were expressed as mean or percentage. Descriptive statistics such as mean values and percentages were used for continuous and categorical data, respectively. The SD was also calculated for each continuous variable analyzed (age, body mass index [BMI] and QTc).

RESULTS

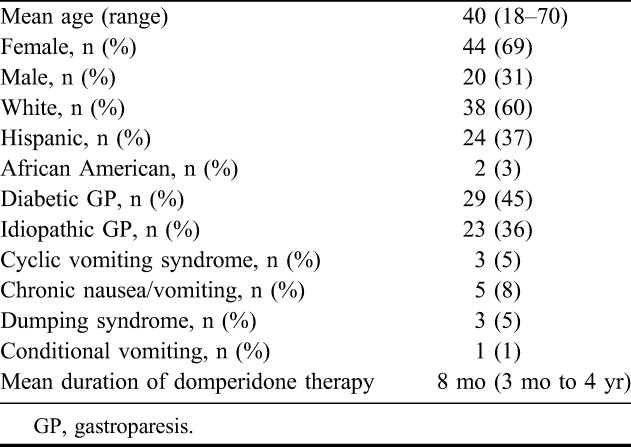

Overall, 64 patients (44 females and 20 males) were taking domperidone for various time intervals during the period of data analysis from December 2009 to December 2013. The indications for use were diabetic gastroparesis (GP) in 29 (45%); 23 (36%) with idiopathic GP; 5 (8%) with chronic nausea and vomiting; 3 (5%) with dumping syndrome; 3 (5%) with cyclic vomiting syndrome and 1 (1%) with conditioned vomiting (Table 1). The ethnicity among our patient population included 37% Hispanic, 60% white and 3% African American (Table 1). The mean BMI was 25.9 ± 6.7 (SD). Daily doses of domperidone ranged from 40 to 120 mg administered as 10 to 40 mg 30 minutes before each meal and at bedtime. The duration of domperidone therapy ranged from 3 months to 4 years with a mean of 8 months. The dose distribution was 40 mg in 10%, 80 mg in 75% and 120 mg in 15% of patients. Only 3 of the 64 (4.6%) patients chronically receiving high doses of domperidone reported palpitations, without any complaints of chest pain. Their ECGs displayed no QTc prolongation or dysrhythmias. Eight patients (12.5%) had prolactin-related side effects that included irregular menstruation, galactorrhea, breast tenderness and insomnia, but these findings did not required discontinuation of therapy with domperidone. No electrolyte abnormalities were observed. Seventy-three percent of patients assessed their GP symptoms as moderate to markedly improved, specifically related to nausea and vomiting. Nine patients (14%) did not have a positive clinical response to domperidone. One of these 9 patients subsequently responded to amitriptyline administered in a dose escalation manner and 1 receiving chronic medication for pain, improved symptoms with use of the narcotic antagonist methylnaltrexone. The remaining 7 patients who had failed all other therapies and now did not respond to at least 3 months of high-dose domperidone underwent placement of a gastric electrical stimulation system (EnterraTherapy).

TABLE 1.

Summary of the demographic data for 64 patients receiving chronic high doses of domperidone therapy (90% receiving a dose of 80–120 mg/d)

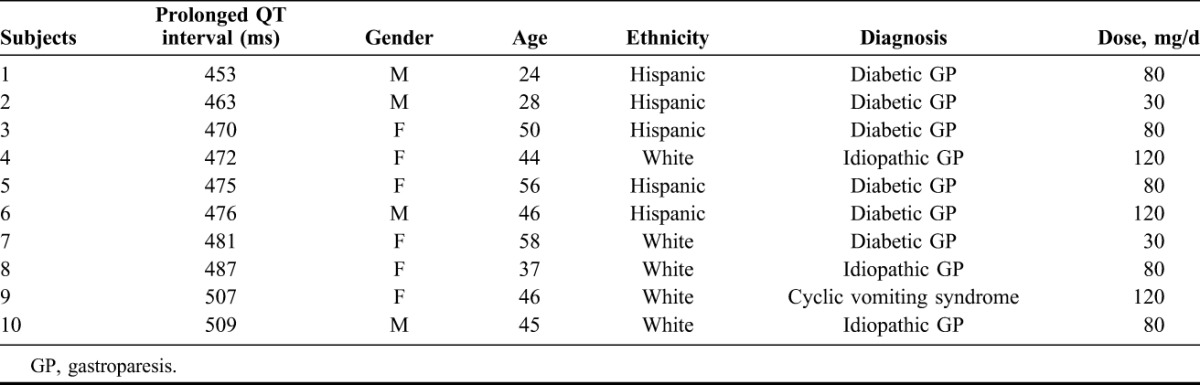

Thirty-seven of the 64 patients had a baseline as well as follow-up ECG available for analysis. The mean QTc interval at baseline ECG was 424 milliseconds ± 28.4 (SD) compared with 435 milliseconds ± 27.2 (SD) on follow-up, a nonsignificant difference. Ten of these 37 patients (27%) had a prolongation of their QT interval ranging from 453 to 509 milliseconds with the mean value of 476.8 milliseconds ± 18.3 (SD) noted on their follow-up ECG (Table 2). The mean age of these patients was 43.8 years ± 14.5 (SD) (range, 24–58 years) with 4 males and 6 females. The mean BMI of those patients with a prolonged QT interval was 23.6 ± 6.7 (SD) (range, 18–29). The mean of prolonged QTc intervals for males was 475.3 milliseconds ± 24.4 (range, 453–509) and for females, 482 milliseconds ± 13.7 (SD) (range, 470–507). Their diagnoses varied from 60% diabetic and 30% idiopathic gastroparesis to 10% with cyclic vomiting syndrome. No correlation was identified between the degree of QTc prolongation and the dose of domperidone. Three patients were taking a maximum dose of 120 mg/d, 5 were on 80 mg/d and 2 were on 30 mg/d. All patients with a prolonged QT interval were asymptomatic and specifically did not have any CV complaints and no arrhythmia or other ECG changes were observed. Once the QTc prolongation was noted on follow-up ECG, the patient was advised to discontinue the medication.

TABLE 2.

Information on the demographics and clinical data of the 10 patients identified as having prolonged QTc intervals while receiving chronic high doses of domperidone

DISCUSSION

The study analysis demonstrates that 73% of the patients receiving chronic high-dose domperidone treatment had a clinically meaningful improvement in their symptoms of nausea and vomiting. The BMI did not have any correlation with patients who had a prolonged QTc. CV complaints of palpitations were reported by 3 patients only, without accompanying prolongation of QT intervals, and also, none of the patients had any evidence of arrhythmias or SCD. The 27% of patients who had QTc prolongation did not exhibit any CV complaints, and their age did not correlate with the risk of having a prolonged QTc interval. Diabetes was the major comorbid condition in 60% of subjects with prolonged QT. This number is compared with the presence of diabetes in 45% of the overall patient population with nausea and vomiting, suggesting that diabetes may be a predisposing factor for QTc interval changes with chronic domperidone therapy.

Based on a handful of European clinical trials, questions were raised in the past concerning domperidone's potential to cause QTc prolongation with increased potential for ventricular arrhythmias. A nested case-control study from the Netherlands5 reported an increased risk of 44% for serious ventricular arrhythmias (SVA) and SCD with a domperidone dosage of 40 mg/d orally compared with proton pump inhibitor use only. They also determined that there was a 59% increased risk of SVA or SCD with domperidone use compared with nonusers of either agent in a multivariate analysis. A subgroup analysis suggested an increased risk of SVA/SCD in males and elderly individuals (age >60 years).5 Interestingly, our study showed no relationship to increasing age and the likelihood of QTc prolongation, and again, our demographic distribution indicates that GI motility disorders such as gastroparesis are dominated by female. Another case-control study in the Netherlands by Van Noord et al4 reported an increased risk of SCD in individuals receiving higher dosages of domperidone, defined as a dose of domperidone of more than 30 mg/d without any specific information on the specific doses being used in these subjects.

Sawant et al performed a trial of 52 patients who received 10 mg of domperidone 3 times per day for 2 weeks and had no prolonged QTc interval effects.15 Rossi and Giorgi11 in a systematic review identified 21 studies that investigated domperidone; comprised of 3 in vitro, 1 animal study, 5 cases reports and 12 clinical trials. Twelve of the 21 studies recognized some cardiotoxicity related to IV administration of domperidone, and 2 with the oral formulation.11 Additionally, a few case reports have been published: a 4-month old infant was given domperidone as an indication for gastroesophageal reflux disease at a dose of 1.8 mg·kg−1·d−1 (adults receive <1 mg·kg−1·d−1).6 This infant later developed QTc interval prolongation of 463 milliseconds.6 Another case report described a 33-year-old woman being treated with domperidone concomitantly with fluconazole and she developed a prolonged QTc interval and Torsades de pointes.7 Once this ECG finding was noted, both drugs were discontinued. This clinical observation suggests a potential drug-drug interaction and proposes fluconazole as the offending agent and raises the question for future research as to whether other agents working through the P450 cytochrome metabolic pathway may be a risk factor for prolonged QTc. It is important to note that this patient was also affected with systemic lupus erythematosus, a disease potentially associated with an inherent risk of QTc prolongation as suggested by recent mounting evidence.16

This study is unique in that 90% of the patients were receiving very high doses of domperidone ranging from 80 to 120 mg/d for greater than 3 months. Even with this very high dosing of domperidone, no SCD/SVA, Torsade de pointes or other arrhythmia occurred, and there were no CV complaints except for palpitations in 5% of patients. The authors believe that it is the first observational study in the United States that has attempted to analyze dosing efficacy and the CV safety profile of domperidone. The limitations of this research study are that it is a retrospective medical chart review with relatively small number of patients. In defense of these limitations is that it represents the largest population ever reported in the world's literature with chronic oral dosing of domperidone exceeding 40 mg per day. In addition, since our data collection relied on patient adherence to regular ECG follow-ups requiring their availability to return to a University Medical Center, there was predictably some loss to follow-up occurring. To offset this aspect, regular telephone contacts with out-of-state patients and their primary care physicians were done to obtain ECG results and assess the clinical status of some of the subjects.

In a review of domperidone by Reddymasu et al,8 clinical trials comparing domperidone in doses of 40 to 80 mg for 4 weeks to either placebo or metoclopramide in diabetic gastroparetic patients showed a clinical superiority for domperidone.17–21 Their conclusions were that domperidone is a safe and effective antiemetic and prokinetic medication for patients with gastrointestinal symptoms of nausea and vomiting, particularly for gastroparesis. The lack of access to this drug in the United States limits its legal use to a few University motility centers. The authors recommend further research studies and clinical trials be conducted to enhance our knowledge and understanding of this very effective agent. Based on the results of this research, the authors can state that domperidone is safe, even when taken in very high doses, and its utilization in the United States should be endorsed while at the same time encouraging adherence to appropriate protocols to continue to monitor for cardiac events and ECG changes.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Presented as a poster at the Annual American Gastroenterology Association Meeting—Digestive Diseases Week 2014, Chicago, IL.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drolet B, Rousseau G, Daleau P, et al. Domperidone should not be considered a no-risk alternative to cisapride in the treatment of gastrointestinal motility disorders. Circulation 2000;102:1883–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green LW, Ottoson JM, Garcia C, Hiatt RA. Diffusion theory and knowledge dissemination, utilization, and integration in public health. Annu Rev Public Health 2009;30:151–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyce MJ, Baisley KJ, Warringon SJ. Pharmacokinetic interaction between domperidone and ketoconazole leads to QT prolongation in healthy volunteers: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012;73:411–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Noord C, Dieleman JP, van Herpen G, et al. Domperidone and ventricular arrhythmia or sudden cardiac death: a population-based case-control study in the Netherlands. Drug Saf 2010;33:1003–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johannes CB, Varas-Lorenzo C, McQuay LJ, et al. Risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death in a cohort of users of domperidone: a nested case-control study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2010;19:881–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rocha CM, Barbosa MM. QT interval prolongation associated with the oral use of domperidone in an infant. Pediatr Cardiol 2005;26:720–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pham CP, de Feiter PW, van der Kuy PH, et al. Long QTc interval and torsade de pointes caused by fluconazole. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:1456–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddymasu SC, Soykan I, McCallum RW. Domperidone: review of pharmacology and clinical applications in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:2036–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, et al. , Gastroenterology ACo. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:18–37; quiz 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alam U, Asghar O, Malik RA. Diabetic gastroparesis: Therapeutic options. Diabetes Ther 2010;1:32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossi M, Giorgi G. Domperidone and long QT syndrome. Curr Drug Saf 2010;5:257–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pointe ML, Keller GA, Girolamo GD. Mechanisms of drug induced QT interval prolongation. Curr Drug Saf 2010;5:44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Straus SM, Kors JA, De Bruin ML, et al. Prolonged QTc interval and risk of sudden cardiac death in a population of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:361–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moskovitz JB, Hayes BD, Martinez JP, et al. Electrocardiographic implications of the prolonged QT interval. Am J Emer Med 2013;31:866–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawant P, Das HS, Desai N, et al. Comparative evaluation of the efficacy and tolerability of itopride hydrochloride and domperidone in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. J Assoc Physicians India 2004;52:626–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazzerini PE, Capecchi PL, Guideri F, et al. Connective tissue disease and cardiac rhythm disorders: an overview. Autoimmun Rev 2006;5:306–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heer M, Müller-Duysing W, Benes I, et al. Diabetic gastroparesis: treatment with domperidone–a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Digestion 1983;27:214–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch KL, Stern RM, Stewart WR, et al. Gastric emptying and gastric myoelectrical activity in patients with diabetic gastroparesis: effect of long-term domperidone treatment. Am J Gastroenterol 1989;84:1069–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson D, Abell T, Rothstein R, et al. A double-blind multicenter comparison of domperidone and metoclopramide in the treatment of diabetic patients with symptoms of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:1230–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silvers D, Kipnes M, Broadstone V, et al. Domperidone in the management of symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis: efficacy, tolerability, and quality-of-life outcomes in a multicenter controlled trial. DOM-USA-5 Study Group. Clin Ther 1998;20:438–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horowitz M, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, et al. Acute and chronic effects of domperidone on gastric emptying in diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Dig Dis Sci 1985;30:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]